Mikkelsen A., Langhelle O. (eds.) Arctic Oil and Gas. Sustanability at Risk?

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ILO 169 (1989) ILO Convention 169 Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in

Independent Countries, Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2005) Report no 30 (2004–2005) to the Storting:

Opportunities and Challenges in the North.

Oskal, N. (2001) ‘Political inclusion of the Sami as indigenous peoples in Norway’,

International Journal of Minority and Group Rights, 8.

Royal Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion, The (2006) Guidelines for Consultations

Between State Authorities and the Sami Parliament and Other Sami Entities (Norway),

Oslo: The Royal Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion.

Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) (2002) Policy paper,

July 1, in Moscow: RAIPON.

Salim, E. (2004) Striking a Better Balance: Extractive Industries Review Report, Jakarta:

The World Bank Group.

Schrijver, N. (1997) Sovereignty over Natural Resources: Balancing Rights and Duties,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stavenhagen, R. (2001) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human

Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People, Geveva: United Nations

Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights.

Stavenhagen, R. (2003) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human

Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous Peoples, Geneva: United Nations

Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights.

Thornberry, P. (2002) Indigenous Peoples and Human Rights, Manchester: Manchester

University Press.

Tribe, L. (2000) Tribe’s American Constitutional Law, 3rd edn, New York: Foundation

Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. ([1999] 2005) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous

Peoples, London: Zed Books.

UNHDR (2004) ‘Cultural liberty in today’s diverse world’, in United Nations

Development Programme (UNDP; ed.) Human Development Report, New York: UNDP.

United Nations (2007) United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,

New York: United Nations. Available HTTP: http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/

GEN/N06/512/07/PDF/N0651207.pdf?OpenElement.

World Bank (2006) Safeguard Policies with Respect to Indigenous Peoples, Washington:

World Bank.

World Bank (2007) ILO Convention 169 and the Private Sector. Available HTTP:

http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/enviro.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/p_ILO169/$FILE/ILO_169.

pdf (Accessed 11 April 2008).

316 K. F. Hansen and N. Bankes

12 Perceptions of Arctic

challenges

Alaska, Canada, Norway and

Russia compared

Oluf Langhelle and Ketil Fred Hansen

Introduction

As should be evident from the previous chapters, the framing of Arctic challenges

varies significantly in the different countries covered in this book. In this chapter

we aim to bring the material from the four countries – Alaska, Canada, Norway

and Russia – together in a comparative context from the perspective of sustain-

able development. We want to identify, highlight and discuss differences

and similarities in more detail within the overall research questions raised in the

introduction: What is sustainable development believed to entail, and what does

it imply for oil and gas activities in the Arctic? What are the main conflicts of

interests between different groups of actors? How and why do the main concerns

and conflicts vary between indigenous peoples, local people, governments and oil

and gas companies in the different regions and countries?

Although differences may seem to be most visible, there are also striking

similarities between different regions and countries when it comes to the framing

of issues and challenges. In addition, there seems to be a common struggle, and

attempts across regions and countries to reconcile different interests and concerns

in the Arctic. No doubt, the work of the Arctic Council has contributed to this

development, providing a common agenda for the different Arctic countries,

at least within the Council. But independent of the activities in the Arctic Council,

there is also an increasing interaction among different groups and actors across

regions. Obviously, the oil and gas companies have for years operated in different

regions, but there is now growing cooperation in the Arctic among scientists,

academics, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and indigenous peoples

focusing on similar issues and concerns. This increase in cooperative efforts has

arguably led to an increasing transfer of ideas and possible solutions moving from

one institutional, political and cultural setting to another. The possibility of find-

ing common solutions across regions and countries is discussed in this chapter.

From the four country chapters, it is evident that oil and gas activities in the

Arctic have only partially been framed directly in the idiomatic wording of sustain-

able development. Despite this, however, it is apparent that much of the discussion

within the four countries can be linked and interpreted within a sustainable

development frame. Sustainable development has become fairly widespread in the

political vocabulary in all the countries, although there are noticeable differences

among them. Sustainable development is most commonly used as a frame for

national policies in Norway and Canada, followed by Russia and then the United

States (US). A central issue in sustainable development, however, is the balance

between development and the environment. Although not always explicitly linked

to sustainable development, the balancing of social, economic and environmental

concerns figures prominently in all the national debates.

The rest of the chapter proceeds as follows. As our point of departure we focus

first on the framing and identified challenges of oil and gas activities in the Arctic

from a sustainable development perspective under the headings of developmental

challenges, environmental challenges and indigenous peoples. Although these

issues are addressed under separate headings, there are important linkages among

them, which we also try to highlight. Second, from this comparison, we try to

provide some reflections on what the global sustainable development agenda may

imply for the further development of oil and gas in the Arctic.

Sustainable development and development

concerns in the Arctic

It is a widely held perception in all the countries that oil and gas can benefit devel-

opment in terms of job creation, profits and welfare in the Arctic.

1

Local and national

politicians, indigenous peoples and other local inhabitants, together with the differ-

ent oil businesses all emphasize this. The debates and story lines are first and fore-

most tied to the circumstances or conditions under which oil and gas is seen to be

beneficial. These conditions vary somewhat among different stakeholders. At the

local level, however, there seems to be general support for the conclusion in Arctic

Human Development Report (AHDR, 2004) that the key sustainability challenge

seen from the Arctic is how to ensure that more of the profits from resource extrac-

tion actually remain in the Arctic. Within the four countries, this is perhaps the

perception that is most consistently advocated by local and indigenous peoples.

Although the strategies followed are somewhat different, the success in capturing

profits varies and the story lines that frame the message are different.

Economic challenges

Another way of framing this story line is through the question, who will benefit

from increased oil and gas production in the Arctic? As we saw in Chapter 2, equity is

inherent in the concept of sustainable development. How one answers this question

determines to a high degree the attitudes towards oil and gas development in the Arctic.

This question can also be linked to the perception of the Arctic as a storehouse of

resources. As argued in Chapter 2, the study conducted by Glomsrød (2006) confirms

the findings of the AHDR report. According to Duhaime and Caron (2006: 22):

The circumpolar Arctic is exploited as a vast reservoir of natural resources

that are destined for the southern, non-Arctic, parts of the countries that also

318 O. Langhelle and K. F. Hansen

include Arctic regions, and more broadly to global markets. The Arctic is a

major producer of hydrocarbons, minerals and marine resources, whose

importance is confirmed by the very value of the resources produced. The

economy of the Arctic is also characterized by large service industries,

particularly through the role of the State. Finally, it is characterized by a

limited secondary sector . . . .

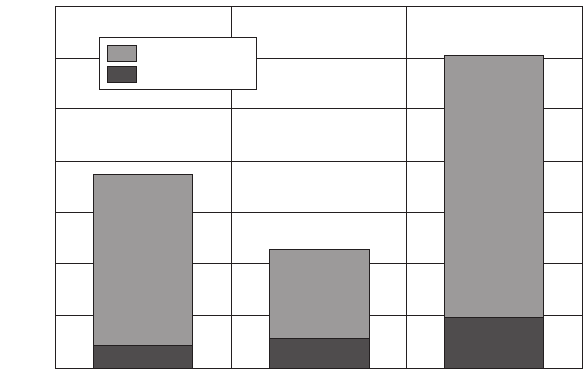

These resources are petroleum, minerals, fish and forests. Of these resources,

petroleum dominates the resource extraction industries. The Arctic share of

global oil and gas production is significant, respectively 10.5 and 25.5 per cent

(Figure 12.1). Around 97 per cent of the present Arctic oil and gas production is

taking place in Alaska and Northern Russia (Lindholt, 2006).

In addition, the Arctic has 12.7 per cent of the proven petroleum reserves, and

23.9 per cent of undiscovered petroleum resources. The Arctic, therefore, has the

potential to continue to supply around one-quarter of the total demand of global

gas consumption (Lindholt, 2006: 29).

The Arctic region per se, contributes to 0.44 per cent of the world’s total gross

domestic product (GDP), while its population only represents 0.16 per cent

(Duhaime and Caron, 2006: 17). Thus, income generation per capita in the Arctic

in general is higher than for the rest of the world in general. However, for the

countries having parts of their territory in the Arctic, the income per capita

produced in the Arctic per se, represents only 80 per cent of the national

per capita income. This again varies a lot from country to country and certainly

from locality to locality within the Arctic zone. In the Russian Arctic, for

Perceptions of Arctic challenges 319

Million barrels of oil equivalents per day

Rest of the world

Arctic

140

10.5 %

25.5 %

16.2 %

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

Oil Gas Total petroleum

Figure 12.1 Arctic share of global petroleum production, 2002. (Source: Lindholt, 2006: 27.)

example, per capita GDP is 219 per cent of the Russian average, while in the

Arctic zone in Norway the GDP per capita is only 56 per cent of Norway’s

national average (Duhaime and Caron, 2006: 18).

Generally speaking, the Arctic contributes to the global economy by energy

and raw materials like oil, gas, diamonds, gold, wood, fish and shrimp, while it

imports final goods and services (Duhaime and Caron, 2006: 20). This resembles

the characteristics of a developing country. One of the major challenges, therefore,

for businesses generating these large income streams and for official authorities

in the Arctic countries, is to distribute the benefits in a way that the different

populations in the Arctic find fair and just.

What the various populations in the different Arctic countries find fair and just

however, varies significantly. At a general level, a common point is that the local

inhabitants of the Arctic, indigenous peoples included, want the resources

extracted from the Arctic to benefit their own region. Thus, most Arctic inhabi-

tants agree that a fair distribution of resources implies that there should be more

re-invested in the zones where it is extracted than currently takes place.

Arguments for this view vary. Some local people use as their main argument the

moral commitment states have to ensure equal opportunities between people.

They use statistics on relative underdevelopment in their region compared to

other regions in their countries to support their views.

Others, especially some indigenous peoples in Norway and Russia, refer to

ILO 169 and other national laws in order to claim that the resources legally

belong to them. The Russian Sámi President, Alexander Kobelev, for example,

argued at the Arctic Council meeting on October 26, 2006, that:

The Saami have watched states build a large part of their wealth on our rivers,

fjords, mountains and forests. We will watch no longer. We have to enter a

new phase where governments and multinational corporations stop doing the

wrong things, and start doing the right. We have never given up our inherent

right to our territories, however, for large parts of the Saami area our land and

governance rights are still not respected.

2

Generally speaking, indigenous groups tend to be both politically marginalized and

poor in monetary terms. However, for indigenous peoples within the Arctic, the

degree of marginalization and poverty varies a lot. Some groups of indigenous

peoples are richer than their national average, while most still live in monetary poor

conditions. For example, even if the GDP per capita in the Canadian Arctic

represents 155 per cent of the Canadian national average (Duhaime and Caron,

2006: 18), indigenous peoples have a 25 per cent higher unemployment rate than

other Canadians. A 65 per cent higher proportion of indigenous people than other

Canadians have poor housing and 42 per cent more live on social welfare. Thus, even

if the Arctic as a whole represents a larger percentage of the national economy than

of the population, only a small minority of the people living there benefit from this.

Few in Norway would be classified as poor in a global monetary way of

measuring it. On average, Norway disposed of 38,400 US$ (purchasing

320 O. Langhelle and K. F. Hansen

power parity; PPP) (UNDHR, 2006: 283–284). Norway has been among the ten

richest countries in the world every single year for the last decade (UNHDR,

2006). However, the northernmost inhabitants in Norway lag behind the national

average income (22 per cent lower than the national average income; Statistisk

Sentralbyrå, 2006).

Income statistics for indigenous peoples Russia are not available. However,

Russia had a per capita gross domestic product of only 9900 US$ (PPP) in 2004

(UNHDR, 2006: 283–284). In addition to a relatively low GDP per capita, the

difference between the rich and the poor is greater in Russia than in Norway.

While the poorest 10 per cent in Norway receive 3.9 per cent of the income,

in Russia they receive only 2.4 per cent of income (UNHDR, 2006: 335–336).

To develop oil and gas activities in the Arctic further, one of the major concerns

will thus be the question of distributing profits back to the localities in an

equitable manner. The various states in question do this only to a certain degree.

Norway, the only unitary welfare state under scrutiny, does this to a relatively high

degree, while Russia redistributes resources back to the peripheries only to a

limited degree.

Many indigenous groups would not measure poverty in monetary terms,

but rather in terms of opportunities or possibilities to keep their identity as indige-

nous peoples. The identity is very much linked to language, religion and

occupancy. The relationship to land is for all indigenous peoples a central factor

for their identity. ‘You do not share your money but you share your food. If you

yourself have caught and prepared your food, sharing it represents something

totally different from sharing money’. A recent study shows that 90 per cent of

indigenous peoples households in the Arctic report sharing subsistence food with

other community members and/or family (Poppel, 2006: 71). This also points to

the fact that subsistence hunting, harvesting and fishing represent an important

part of the economy in many places of the Arctic, and makes them especially

vulnerable to pollution and climate change.

However, the subsistence economy is never factored into regular statistics with

the result that the economic contribution to the economy of indigenous peoples is

neglected, making them richer than statistics suggest. Yet, the value of land

will thus also be neglected in economic terms, since subsistence economy never

enters statistics. For the Inuit, for example, subsistence ‘means much more than

mere survival or minimum standards of living . . . It enriches and sustains

Inuit communities in a manner that promotes cohesiveness, pride and sharing’

(Poppel, 2006: 66).

For the indigenous peoples in Alaska and Canada, proclaiming property rights

have been the most important strategy for capturing profits, a strategy that to

some extent has been successful. Property rights have also become important

strategies within Russia and Norway. In Russia it has been highly unsuccessful,

and in Norway it remains to be seen whether or not the Sámi people will succeed

in their attempts to get traditional sea rights. In all countries, however, indigenous

peoples advocate a rights-based approach to resources. The story line identified

in the Norwegian chapter, ‘It is our right’, captures the essence of this approach.

Perceptions of Arctic challenges 321

Norway has created an oil fund invested globally to keep some of the extracted

resources available for future generations and not to overheat the national

economy. Still, national and local politicians argue for oil and gas activities in the

Arctic, using the need for job opportunities and increased welfare in Northern

Norway as the arguments. These arguments are added to the main argument for

expanded oil and gas exploration emphasized by national politicians in Norway,

namely the global need for more energy. Helping to meet higher demands

for energy in developing countries has been used by Norwegian oil company

directors as well as Norwegian politicians to argue for a high level of extraction

(Chapter 9). Some politicians have even argued that it is Norway’s moral obliga-

tion to provide parts of this energy and that Norway has a global responsibility to

contribute to poverty reduction in the world by extracting more oil and gas.

Environmentalists and parts of the Sámi community argue against oil and gas

activities, while a majority of the local inhabitants, the Norwegian government

and the oil and gas companies are arguing for extraction now.

Russian legislation favoured devolution during the 1990s, but over the last

decade we have seen an increasing re-centralization of power back to Moscow.

Also, many observers and researchers doubted the application of the laws favour-

ing Northern Russian people and indigenous peoples in Russia during the 1990s

(Caulfield, 2004: 124–125). Russia’s two main motives for exploiting oil and gas

in the Arctic are to satisfy the steadily growing internal demand for oil and gas,

and to secure their status as one of the world’s most powerful countries.

As Andreyeva and Kryukov (Chapter 10) have shown, the collapse of the Soviet

system led to a drastic deterioration in the living standards among a large part of

the population in the Russian Arctic.

Social challenges

Social issues are part of the general orientation towards development in all four

countries under scrutiny. Most often social issues at stake are intrinsically linked

with economic development. Which social issues are dominating the public

discourse, however, varies in the different countries. Abuse of alcohol and social

deprivation are particularly prominent in the stories from local communities and

among indigenous peoples in Alaska, Canada and Russia, but are hardly an issue

in Norway. The main concern in Norway has been linked to employment

opportunities. For all four Arctic regions under study, the unemployment rate is

higher than the national average, life expectancy is lower, health status worse and

the level of education lower than their national average. Yet, in all the four

Arctic regions discussed, statistics on different social issues like education, health

and unemployment show that, in relation to their national average, Arctic

populations are improving rapidly. Thus, the difference between the Arctic

population and the national average is diminishing. Yet, there are still huge

discrepancies.

322 O. Langhelle and K. F. Hansen

Employment

Statistics confirm that most localities in the Arctic lack job opportunities for the

population, and the region is lagging behind in social welfare and industrial

modernization. In Chukotka (Russia), the entire adult population sees unemploy-

ment as a serious social problem, while 83 per cent in Alaska and 87 per cent in

Canada see unemployment as a serious social problem (Poppel, Kruse, Duhaime

et al., 2007: 11). In most parts of the Arctic lacking oil and gas expansion, economic

opportunities have declined during the last few decades. Job prospects and invest-

ments have been reduced. The fish processing industry in Northern Norway,

for example, reduced its numbers of employees by 50 per cent between 2000 and

2004 (Chapter 9). In Nunavut, unemployment is a huge issue (Chapter 8).

In general, the unemployment rate in the Arctic parts of the four countries

covered in this study is higher than their national average. In Arctic Canada, there

are certain regions with a 25 per cent higher unemployment rate than the Canadian

average, while in Norway unemployment is only marginally higher than the national

average. In Russia, the Arctic sub-regions with dominant oil and gas production

have a lower level of unemployment than the national average. However, seen as a

whole, the Russian Arctic has a 1 per cent higher unemployment rate than the

Russian average. Yet, indigenous peoples in the Russian Arctic are four times more

likely to be without employment than their Russian neighbours. In Alaska, the level

of unemployment is higher in the North Slope than the state average.

Thus, compared to their national average rate of unemployment, most Arctic

regions face a relative disadvantage.

In most regions in the Arctic, formal unemployment is a problem. Most local

inhabitants and local politicians argue that development of further oil and gas

activities in their region should benefit the local population with job opportuni-

ties. However, there is a high degree of uncertainty surrounding job opportunities

for the local population. Some fear that the jobs offered to the local inhabitants

are temporary, short-term jobs relating mostly to the construction phase of oil and

gas investments, while the more permanent jobs for experts will be given to

specialist from other regions just coming to the Arctic to work, while continuing

their urban living in cities outside the region. Thus, they fear that strangers will

profit more than themselves. The divide between higher-paid specialist jobs taken

by southerners and lower-paid unskilled workers from the Arctic will create

tensions in the different Arctic localities. Michael Baffrey, working on the Arctic

Council’s Oil and Gas Assessment Report, argues that oil and gas employment in

itself is highly variable and ultimately unsustainable.

3

Job estimates connected to oil and gas activities vary. For Norway, estimates vary

from an optimistic 10,000 new jobs to zero effect in relation to the expanded oil and

gas exploration in the Norwegian Arctic (Chapter 9). However, how many of these

positions will go to locals is highly uncertain. Fewer people living in Northwest

Russia think increased oil and gas activities in the area will make a positive

long-term impact on local employment (Hønneland, Jørgensen and Moe, 2007).

Perceptions of Arctic challenges 323

Highly educated experts from the Southern parts of Russia or from abroad are likely

to take the most attractive jobs (Chapter 10). Jobs in Arctic Canada are scarce,

and most locals argue that oil and gas development creates opportunities for

employment.

However, people need to have specialist training to get the more attractive

jobs in the oil and gas sector. Without special attention paid to adequate training,

the job opportunities offered in the oil and gas sector will mostly benefit educated

people from other regions in Canada than the Arctic. Where indigenous peoples

have created joint venture business corporations with leading oil and gas compa-

nies, it seems that specialized training and employment possibilities for local

people are better than where this has not happened (Chapter 8). In Alaska, local

employment in the oil fields is low. More than 5000 non-residents commute to

North Slope oil-field jobs from outside the region. Most local, indigenous people

work in government, construction, service and support sectors fuelled by oil tax

revenues. The unemployment rates for North Slope residents are a little higher

than for the state as a whole: 7.0 per cent versus 6.7 per cent in 2006 (Chapter 7).

In the Arctic, how much of indigenous peoples’ standard of living comes from

subsistence farming, fishing and hunting varies a lot. In the Northern Slopes

(Alaska), more than half of the population gain more than half of their food from

subsistence resources. In Norway, most of the Sámi population is living in the

capital city of Oslo and have regular paid urban jobs. A total of 2914 persons were

connected to reindeer herding activities in Norway as of November 2005; 609 out

of these classified themselves primarily as reindeer herders holding their own

herd (Statistisk Sentralbyrå, 2006: 81). Only a few hundred Sámi make their

direct living from reindeer herding in the Arctic parts of Norway.

In all the Arctic states, the ability for indigenous peoples to continue their main

traditional occupations while working for an oil and gas operator is important.

In Northern Alaska, 77 per cent of the population argue that their preferred

lifestyle is to combine traditional subsistence activities with a wage job. In

Russian Chukotka, 39 per cent answer they would like a waged job, while

29 per cent would prefer a combination of wages and subsistence (Poppel, Kruse,

Duhaime et al., 2007: 8). The cycles followed by animals and nature make differ-

ent periods of the year especially important for various indigenous occupations.

To be able to survive as indigenous peoples, it is critical to reserve certain

periods of the year to traditional activities. Thus, for most indigenous peoples in

the Arctic, it is very important that employment in the oil and gas sector offers

flexible solutions to these needs.

Health

In the various Arctic countries, health issues are of equal importance to local

inhabitants. In the past 50 years, the burden of mortality and morbidity has

declined in all areas of the Arctic. Average life expectancy has increased in

all countries but even more in their Arctic parts. In the US, for example,

life expectancy has increased by nine years since the 1950s, while it has increased

324 O. Langhelle and K. F. Hansen

by 14 years in the Arctic part of the US (Hild and Stordahl, 2004). In Canada,

we find a similar pattern with an increase of 15 years for indigenous peoples

during the past 50 years (Hild and Stordahl, 2004). In Norway, life expectancy for

indigenous peoples has increased and is now close to the national average

(Statistisk Sentralbyrå, 2006). In Russia, we notice substantially increased life

expectancy up to 1990. From 1990 to 2004, life expectancy at birth declined by

as much as seven years (ROSSTAT, 2004). Life expectancy at birth may be taken

as an indicator of the general development and health status of the population. As

another measure, 89 per cent of indigenous people in Alaska, Canada and Russia

report that their health is ‘good’ or ‘better’, 8 per cent report it to be ‘fair’ and

only a small 3 per cent report their own health to be ‘poor’ (Poppel, Kruse,

Duhaime et al., 2007: 22).

Education

Few people in the Arctic see lack of education as a serious problem. There is little

educational difference between the Arctic parts of Norway and the rest of the

country. However, among the Sámi people, only 15.4 per cent (compared to the

national average of 24.8 per cent) have higher education. In Russia, the level of

higher education for people in the Arctic is close to the national average, but the

level of education for indigenous peoples in the Arctic is three times lower. Alaska

has much lower rates of high-school graduation than the nation as a whole, and

within the state Alaska, Native students have the lowest rates of all: as of 2005,

only 43 per cent of Alaska native youth graduate from high school (Leask and

Hanna, 2005). In Canada, low graduation level among indigenous peoples is

perceived as problematic, especially in Nunavut. Thus, when it comes to educa-

tion, the Arctic parts of the states in this study follow their national averages

closely, while the indigenous peoples in the Arctic are lagging seriously behind.

As a conclusion, we may claim that developmental concerns for the different

Arctic peoples in the various states reveal similar dilemmas. First, most people

living in the Arctic compare themselves in development measures to the Southern

population in their own country, rather than their counterparts in other Arctic

states or others within their ethnic group. Second, most people in the Arctic,

whether indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities or just local nationals, are eager to

see the development of oil and gas in their regions. Yet for this development to be

successful, major concerns have to be addressed. Jobs have to be offered to locals,

investments in collective local infrastructure have to be made, education opportu-

nities have to be given and for the indigenous peoples, their cultural, social and

legal rights have to be respected. This includes participation and influence in the

planning of projects proposed on their traditional land.

Environmental concerns

Since the launch of the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS) in 1991,

there has been a strong focus on environmental issues in the cooperative efforts

Perceptions of Arctic challenges 325