Mackesy P. The War for America, 1775-1783

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

page_123

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_123.html[1/17/2011 2:25:42 PM]

< previous page page_123 next page >

Page 123

Trusting therefore to Howe's assertion of the importance of Philadelphia, Germain agreed to his change of plan: he

only added the hope that Howe would really complete his operation in time to co-operate with the Canadian army.

Indeed the plan had reached London so late that Germain had no choice but to agree; and his answer, though

promptly given, did not reach Howe till the middle of August, when the dilatory expedition was already in the

Chesapeake. The responsibility was Howe's alone; and Howe had no reason to fear that the plan would hurt

Burgoyne. On 16 July, before he sailed for the south, he received a letter from Burgoyne himself, written before

Ticonderoga in high spirits and only lamenting that he had no latitude to reduce New England on his own. Howe

foresaw only one danger to the northern army: that Washington would leave Philadelphia to its fate and turn

against Burgoyne. To guard against this he resolved to make his own approach to Philadelphia by way of the

Delaware instead of the Chesapeake, in order to be in closer supporting distance of the Hudson. If Washington

marched north to attack Burgoyne, Howe thought Burgoyne was strong enough to check him; while if he merely

attempted to retard Burgoyne's advance on Albany he ran the risk of being caught between two British forces.

But if Washington stayed to defend Philadelphia, Howe could see none but administrative obstacles to Burgoyne's

advance. Scarcely anyone, least of all Burgoyne, seems to have realised the real nature of the danger, which lay in

the difficult country and the New England militia. Only that able and difficult officer Charles Stuart, the future

conqueror of Minorca, saw what might happen. He could scarcely believe, when the army embarked, that it was

not a feint; for if Howe's army went south instead of north, Burgoyne would have to fight his way unaided against

the most powerful, inveterate and populous of the colonies. 'I tremble for the consequences', he wrote.1

In England the slow unrolling of Howe's campaign was also watched with an eye to its effect on Burgoyne. But

Howe was no letter-writer; and when he did write he said little to reveal his intentions or explain the long delay in

embarking. In the middle of August Burgoyne was known to be on the move and about to invest Ticonderoga.

Howe had sallied out to look at Washington, and it was known by a private ship that he had then embarked; but

whether for Philadelphia or the Upper Hudson was a mystery. The summer was already far gone, and fears began

to be aired that he would leave Washington free to turn on Burgoyne. Robinson tried to reason himself and others

into believing that Howe would go northwards; but though North, Germain and the Adjutant-General agreed with

his logic, they still feared that the army had gone to Philadelphia. On 22 August there was still

1 Sackville, II, 667, 73; CO 5/94, ff. 269, 286; Fonblanque, 233; Wortley, 113.

< previous page page_123 next page >

page_124

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_124.html[1/17/2011 2:25:43 PM]

< previous page page_124 next page >

Page 124

no news of his intentions, 'for which and for something effectual to be done we grow very impatient'. That very

day, however, despatches arrived, including his letter of 16 July with his cheerful news of Burgoyne. Even then he

had not sailed, and gave no reason for his delay. But Germain had at least the assurance that he was acting on the

fullest information, and did not doubt that he would take the best measures to meet the situation. Robinson was

more sceptical. Howe had written that he 'trusted' Burgoyne would be able to give a good account of the

Americans on the Hudson even if they were aided by Washington; which Robinson thought was trusting a good

deal. 'In this case we here trust, and we hope Howe had provided so, that Sir Henry Clinton may be able to move

from New York to aid Burgoyne . . .'1

2

Delays in the South

The Ministers at home had good reason for their bewilderment. For by September even Howe expected Burgoyne

to reach Albany. Yet it was not till the last days of August that he made his landing in Pennsylvania and opened

the campaign. The southern army would not be ready to open the lower Hudson and co-operate with the Canadian

force before the winter. How had Sir William wasted the whole summer before he struck his blow?

Though he had written in his despatch of 2 April that he meant to avoid offensive operations in the Jerseys unless a

very good opening appeared, Howe resolved in the end to offer one final challenge to Washington before he

embarked, in order either to bring on a battle or at least to secure his embarkation, about which he felt some

anxiety. It was not till the end of May that he took the field, a delay later attributed by Cornwallis and General

Grey to the necessity of waiting for green forage on the ground.2 On 8 May he received Germain's approval of his

second plan, the march on Philadelphia. On the 24th drafts from England began to arrive, which raised the strength

of his whole command to 27,000 men; and about the same time Washington moved south with 8,000 men to be

nearer the British road to Philadelphia, and took up a new position near Bound Brook. Here he was only eight

miles from Howe's post at New Brunswick, and seemed to offer a good chance of forcing him to battle.

Washington's new position was judged too strong to attack. But Howe hoped to lure him into the plain; and

marching from New Brunswick, he thrust forward to cut off an enemy detachment under Sullivan at Princeton. But

Sullivan was hastily and successfully withdrawn without a fight; nor was

1 Add. MSS. 38209, ff. 1523, 155; Knox, 136; Sackville, I, 1389.

2 Anderson, 2407.

< previous page page_124 next page >

page_125

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_125.html[1/17/2011 2:25:43 PM]

< previous page page_125 next page >

Page 125

Washington impressed by the threat to Philadelphia, for he knew that Howe had left his heavy baggage and

bridging train at Amboy. 'The idea of offering them battle is ridiculous', wrote Colonel Stuart, 'they have too much

caution to risk everything on one action . . . If we wish to conquer them we must attack him [Washington], or if his

posts are too strong, by a ruse de guerre place ourselves in that situation he may expect to attack us to advantage.'1

Washington had been tempted in vain; and he was thought too strong to be attacked. It only remained to try a ruse.

On the night of 19 June Howe suddenly decamped, and fell back rapidly on Amboy with all the appearance of a

disorderly retreat. Washington moved forward from his hill position, ready to hinder the British embarkation; and

on the night of the 26th Howe dashed forward to cut his line of withdrawal. Washington escaped precipitately to

the mountains before the trap closed, though one of his divisions was roughly handled, and at last Howe was

satisfied that he would not fight in New Jersey. He had lost a month in the experiment, but secured a peaceful

embarkation. It now remained to be seen whether a seaborne threat to Philadelphia would give him the decisive

battle.

The hottest months of the year had now arrived, and a seasonal south-west wind blew unfavourably. Nearly 14,000

rank and file embarked in their hot and crowded transports between 9 and 11 July; but Howe still waited for news

of Burgoyne. On the 16th came the cheerful letter written before Ticonderoga, and Howe, informed and reassured,

at last commited his own force to the sea.

Yet, dismissing the risk to Burgoyne, as Howe had reason to do, what merit had his own plan? Since Trenton had

renewed his conviction that the Continental army must be destroyed before the rebellion would break, the plan

made sense only on the assumption that Washington would fight for Philadelphia. But would he? As Colonel Stuart

observed, the name of 'capital', so impressive to Europeans who did not know America, had almost no significance

in the decentralised federation of colonies. Moreover, the rebels had had time to remove the military stores whose

loss might have proved decisive at the time of Trenton. Yet for the sake of a doubtful profit, Howe was

abandoning posts in New Jersey which had cost him nearly 2,000 men, and deserting the inhabitants who had

served him. It is said that every general in his army except Grant and Cornwallis disliked the plan. Only two

satisfactory choices were open to Howe: to accept the risks and losses of attacking Washington in New Jersey; or

to leave a covering force there as he had originally planned, and strike northwards to open the lower Hudson.

Howe's own course promised few risks, but fewer gains.2

1 Wortley, 113.

2 Wortley, 113; Anderson, 263; Clinton, 61 et seq.

< previous page page_125 next page >

page_126

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_126.html[1/17/2011 2:25:44 PM]

< previous page page_126 next page >

Page 126

On 23 July a favourable wind at last carried the army to sea. But at the mouth of the Delaware it was met by a

frigate long stationed in the estuary; and so emphatic was her captain about the hazards of navigation and the

strength of the enemy defences that on Lord Howe's advice the fleet changed its course and steered for the

Chesapeake. A year later Sir William was to tell Lord Carlisle that he had switched to the Chesapeake on learning

that the enemy's main magazine was not in Philadelphia but in northern Virginia. But he made no mention of this

at the time; and the whole record is so bedevilled by subsequent polemic that when the source is a man as

inarticulate and unclear as Howe, one must doubt the story.1 In any event, the wisdom of the decision is in doubt.

Evidence suggests that the fleet could have gone up the Delaware without difficulty as far as Newcastle, only a

dozen miles across the peninsula from the eventual landing place in the Chesapeake.

The voyage from the Delaware capes to the head of the Chesapeake took twenty-five days. Not till 25 August did

the army land. During the voyage Howe received Germain's letter of 18 May, approving his plan and echoing his

hope that he could co-operate with Burgoyne before the end of the campaign. But this was no longer possible; and

he replied on the 30th that it was too late. And in spite of reports of a reverse to the northern army at Bennington,

he trusted that Burgoyne would not be prevented from pursuing the advantages he had gained.2

3

The Campaign of Philadelphia

The army which landed at Head of Elk on 25 August had been embarked for forty-seven days, and was as far from

Philadelphia as it had been when it went on board the transports. Its long voyage had meant many days of anxious

speculation for Washington. When the embarkation began he knew, which Howe did not, that Burgoyne had taken

Ticonderoga without a shot and was pushing for the Hudson; and he assumed that Howe was embarking to pierce

the Highlands and join him. Moving towards the Hudson, he sent two divisions across it to Peekskill to guard the

Highland passes. When the British put out to sea, he recalled his detachments and countermarched to the Delaware,

only to fear that he had been misled by a deep feint when the fleet showed itself off the Delaware and vanished

again. After days of indeterminate movements and faulty guesses came the news that the British were high up the

Chesapeake. Washington marched, not north against Burgoyne, but south to oppose Howe, who was to have

1 Carlisle, 254. Cf. the evidence given at the enquiry, that the Delaware was impracticable (Howe's

Narrative, 71 ff.).

2 Sackville, II, 74; CO 5/94, ff. 3134.

< previous page page_126 next page >

page_127

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_127.html[1/17/2011 2:25:44 PM]

< previous page page_127 next page >

Page 127

his battle; and only a handful of riflemen from the main army reached General Gates in the north. The danger to

the force advancing from Canada was a different one, which no British planner had foreseen. 'Now', wrote

Washington, 'let all New England turn out and crush Burgoyne.'

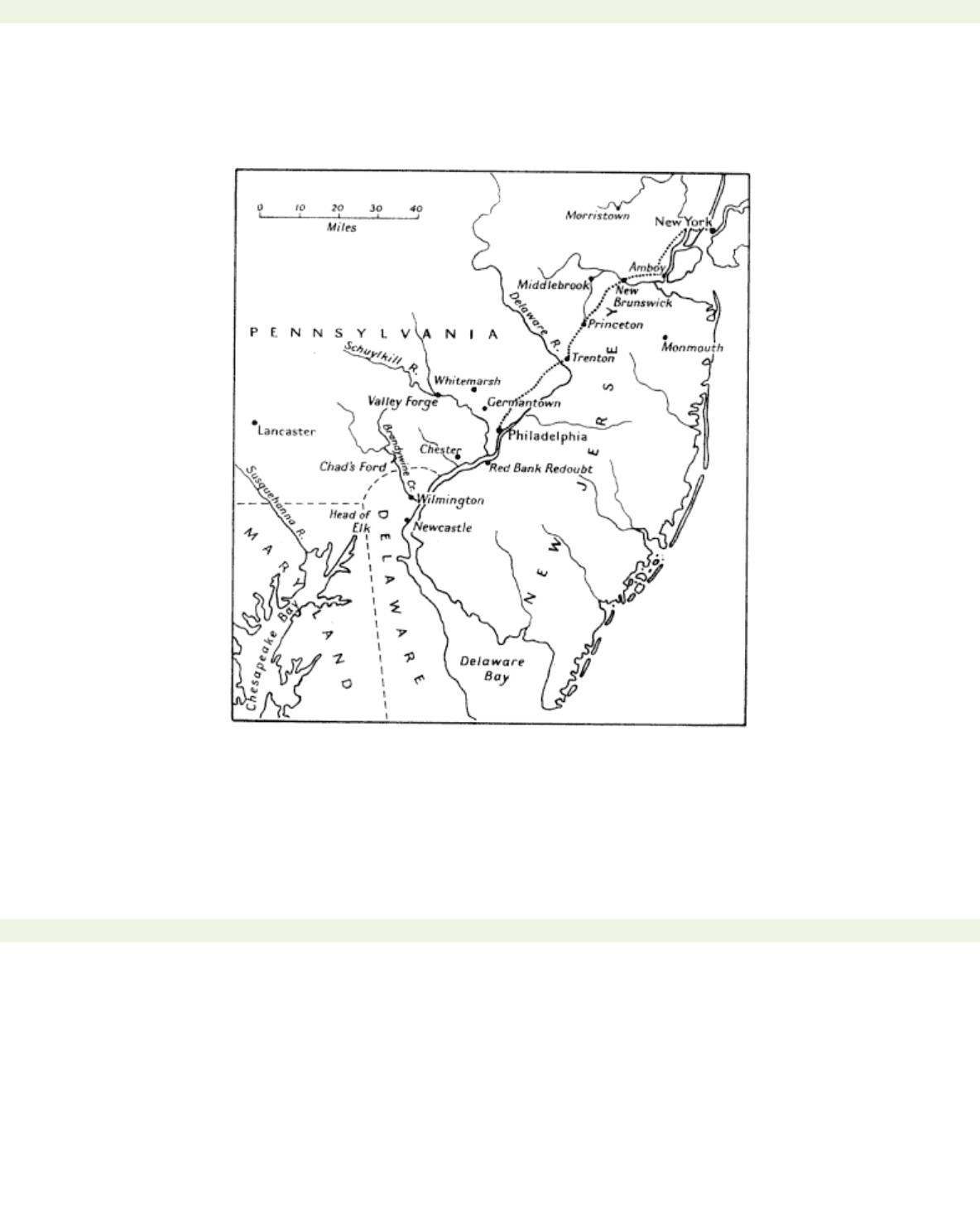

HOWE'S PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN, 1777

In Pennsylvania the odds were less favourable to Howe than in 1776. The two armies were about equal in numbers.

But the Americans now had European instructors, and French arms and cannon. Nor were their backs to a great

river, as they had been on Long Island: there was infinite room for retreat. Howe, for his part, would have to

exploit a victory with speed and

< previous page page_127 next page >

page_128

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_128.html[1/17/2011 2:25:45 PM]

< previous page page_128 next page >

Page 128

energy to reap its benefits. But by choosing an amphibious strategy he had imposed on his army the defective

mobility on shore of an amphibious force. He had two regiments of cavalry in America; but he had brought only

Burgoyne's Sixteenth Light Dragoons to Pennsylvania, leaving the other regiment in readiness to follow him. Thus

the only cavalry at hand to exploit success were three squadrons shared between the divisions of his army. Nor

were they fit for a hard day's work. The heat of the voyage, the rough seas, confinement and shortage of provisions

had made the men suffer. But for the horses it had been catastrophic. They had embarked with three weeks' forage

for a voyage of seven. Many dead and dying horses had gone overboard, and the rest were mere carrion. A Quaker

youth saw Howe himself on the day of the battle of Brandywine 'mounted on a large English horse, much reduced

in flesh'. If the Commander-in-Chief could not keep his charger in condition, the troop horses of the Sixteenth

must have been in a wretched state indeed.1

If it is true that Howe's first object in the Chesapeake had been the magazines in Virginia, it was changed on secret

intelligence that Washington intended to risk a battle. The plan was now to push for Philadelphia and tempt

Washington to fight. On the Brandywine Creek Washington formed his army, and gave Howe his first chance

since White Plains to inflict a decisive defeat. Howe's tactics were the ones he had used so successfully on Long

Island. While Knyphausen with 5,000 men and plenty of cannon demonstrated above the ford on the main road to

Philadelphia, Cornwallis took a wide sweep round the American right flank and made an unopposed and

unobserved crossing of the Brandywine. The Americans had neither reconnoitred nor patrolled the country

properly. Struck in front and flank, they were driven into a general retreat. Washington however had responded

correctly to the crisis by sending a reserve under Greene to hold the road open for his routed right wing.

Cornwallis's men had marched eighteen miles in the heat of the day, and were unable to break Greene's fresh

division and join hands with Knyphausen before dark. Howe halted his troops and allowed the enemy to retire

unmolested into the night.

The ground was said to have been unfavourable for his cavalry. But as the Americans fell back, the road to the rear

became a scene of hopeless confusion. For twelve miles they streamed along in the darkness, intact companies

mingling with dispersed and beaten fugitives. Only at the Chester Creek did Lafayette post a guard on a bridge to

stop the mob, and Greene and Washington arrived to restore order. A cavalry force properly proportioned to

Howe's army and fit for duty might have prevented the enemy from rallying. Two or three regiments of boldly led

dragoons sabreing the

1 Curtis, 126; Ward, 332, 348.

< previous page page_128 next page >

page_129

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_129.html[1/17/2011 2:25:45 PM]

< previous page page_129 next page >

Page 129

stragglers and penetrating the flanks of the retreating column might have spread such confusion as to give a

different turn to the campaign.

So ended a battle which was nearly decisive. Howe's problem was now to cross the Schuylkill and enter

Philadelphia. There followed a period of manoeuvring in which the Americans showed a resilience in defeat which

was astonishing in an army of amateurs, and a power of marching which put the British and Hessians to shame.

But at length, by a series of perplexing movements which alarmed Washington for his right flank and supplies,

Howe drew him away to the west. Then, by a swift march to his right he threw his army across the river.

Washington was twenty miles in the wrong direction, and the road to Philadelphia was clear. On 26 September

Cornwallis entered the city with four battalions. Eight days earlier the Congress had fled to Lancaster.

The success at the Brandywine was spent, and a period of consolidation followed. The immediate task was to clear

the lower Delaware and open communications with the sea. Three battalions crossed the river to clear the forts

commanding the channel, and 3,000 men were sent back to bring up supplies from the beachhead on the

Chesapeake. To cover these operations Howe encamped with the remainder of his force, fewer than 9,000 men, on

the western side of Philadelphia at Germantown. Washington, having summoned reinforcements from the Hudson,

had at least 8,000 Continentals and 3,000 militia. He had just lost the largest city in America; but neither the moral

nor the physical effects were what they would have been nine months earlier. Almost all the stores had been

removed; and his army now had a steadiness on which the purely symbolical loss of the 'capital' had no effect. And

there was news to lighten the load on their spirits. On 28 September, the army celebrated with gunfire and rum the

first exaggerated reports of Gates's victory over Burgoyne in the first battle of Freeman's Farm. Washington could

now 'count on the total ruin of Burgoyne'. He prepared to take the offensive himself, and moved forward to within

twelve miles of the British camp. At the beginning of October he had accurate intelligence of Howe's detachments

and the position at German-town; and with the unanimous support of his generals he resolved to attack it.

A long night march, a complicated plan and a morning fog would have stretched an experienced staff and veteran

troops. The attack was pressed with courage, but it was confused, ill-concerted, and easily unhinged. After initial

success the Americans were repulsed with nearly 1,100 casualties, against Howe's loss of just over 500. Physically

it was a reverse; but the Americans carried off the illusion that the British had been on the point of a general

retreat, the persuasion that Howe's casualties were larger than their own, and the moral sensations of victory. For

Howe the battle could not be

9

< previous page page_129 next page >

page_130

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_130.html[1/17/2011 2:25:45 PM]

< previous page page_130 next page >

Page 130

wholly gratifying. He had not expected so determined a riposte so soon after the Brandywine. Though the attack

was expected, his camp was not entrenched, which he later explained as a deliberate omission 'to create always an

impression of superiority'. But Colonel Stuart may have been nearer the truth with a phrase he had used a month

earlier1: 'our usual carelessness prevails'.

Philadelphia was now secure. It remained to open the Delaware. This proved a long and costly operation,

comparable in importance and trouble with the clearing of the Scheldt in 1944. The army was immobilised for

many weeks. A Hessian assault on one of the American forts was beaten off on 22 October with the loss of the

commander and nearly 400 officers and men. On the same day one of Lord Howe's few ships of the line grounded

in range of enemy batteries and became a total loss. Not till batteries had been laboriously brought to bear by land

and water in the middle of November was the river cleared and the shipping able to move up to Philadelphia.

General Howe, in the meantime, had concentrated his force in Philadelphia. Across the peninsula above the town

he drew a line of fourteen redoubts connected by a strong stockade, anchored on its flanks to the Schuylkill and the

Delaware. Here he was safe from further American insults till the Delaware operations were finished. Then, on the

night of 4 December he sallied to attack Washington's camp at Whitemarsh. But the ground was strong, and after

attempting to feel his way round the American flank he desisted and withdrew to his comfortable winter quarters in

Philadelphia. As yet he had no certain news of the fate of Burgoyne; but rumour was bleak.2

4

The Advance from Canada

Burgoyne had reached Quebec in the first days of May to encounter difficulties which he had not anticipated when

he laid his plans before the Minister. He had expected 2,000 Canadians and at least 1,000 Indians. But these could

not be found. Only 500 Indians came forward; no great loss, for except as scouts they proved worse than useless,

and their savagery made effective propaganda to rally the enemy's militia. But the Canadians were a different

matter. On them Burgoyne had counted to clear his path through the forest. But only about 650 Canadians and

loyalists served with the army.

Transport and supplies proved harder to organise than he had imagined. To make good the deficiency of armed

men, Burgoyne suggested a corvée

1 Wortley, 115; Howe's Narrative, 108.

2 The above account of Howe's operations is based largely on Fortescue, Anderson, Ward, and Freeman.

< previous page page_130 next page >

page_131

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_131.html[1/17/2011 2:25:46 PM]

< previous page page_131 next page >

Page 131

of 1,000 men and 800 horses. But Carleton had long since given warning (or so he claimed) that little help could

be expected from the Canadians after the long disuse of their tenurial obligations: they had been governed, he said,

with too loose a rein for many years.1 As he expected, the response was reluctant. Drivers could not be obtained

for the provision carts; and wet weather and bad roads delayed the movement to the frontier. And Burgoyne

intended to take a powerful train of artillery to the Hudson. Twenty-four pounders and twelve-pounders meant

water-carriage; and there was further delay in making boats for the cannon.2

It was on 20 June, six weeks after Burgoyne's arrival in Canada, that the army assembled on Lake Champlain, soon

after the departure of St Leger's diversionary force to the Mohawk. As had been expected in England, there were

only 7,000 regulars, of whom 3,000 were Germans. But they were good troops, and well led. In General Phillips

and the brigadiers, Burgoyne had brave and proficient subordinates. The Brunswickers were led by Major-General

Riedesel, aged about thirty-eight and recently promoted from the rank of Colonel to lead the contingent: an

excellent officer who spoke English and had made English friends when his regiment was stationed near London in

1756. Above all, Burgoyne had the confidence of his men.

The start had been slow. But Burgoyne set forth with all the optimism of favourable auguries and a sanguine

temperament. And his cheerfulness was soon increased. For on reaching Ticonderoga he found that the American

garrison, 3,000 strong, had failed to occupy a hill commanding the fort. He promptly erected a battery on it, and

the enemy abandoned the works and fled. It was a heavy blow for the rebels. But Washington had taken

Burgoyne's measure, and sent words of reassurance to General Schuyler on the Hudson: ' . . . the confidence

derived from success may hurry him into measures which will in their consequences be favourable to us'.

Burgoyne's own deduction from his success may have had its influence on his later decisions. It was that the enemy

'have no men of military science'.3

It was now the first week of July; and the army had at last reached the point which some believed that Carleton

could have gained in the preceding autumn. Here, if he had had the latitude for which he had asked, Burgoyne

might have turned aside from the path to the Hudson and marched eastwards to the Connecticut valley in the heart

of New England. Much was later made by Burgoyne and his apologists of his lack of choice in the matter; and it is

true that at Ticonderoga he voiced regrets that he had no such latitude. Since it was afterwards implied that this

course would have given

1 CO 42/35, f. 175; CO 42/36, ff. 211, 3267, 329. But cf. p. 59 above.

2 Sackville, II, 112.

3 Fonblanque, 247, 253.

< previous page page_131 next page >

page_132

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_132.html[1/17/2011 2:25:46 PM]

< previous page page_132 next page >

Page 132

the campaign a happier ending, the nature of his regret at the time must be made clear. On his arrival in Canada he

had written to Howe regretting that he had no latitude to make a diversion towards the Connecticut; but on 11 July,

as he committed his force to its southward advance towards the Hudson, he wrote in more precise and ambitious

terms to Germain: 'As things have turned out, were I at liberty to march in force immediately by my left instead of

my right, I should have little doubt of subduing, before winter, the Provinces where the rebellion originated. If my

late letters reached General Howe I still hope this plan may be adopted from Albany . . .' Burgoyne was not

concerned for his army's safety: he believed that with his own resources, and without the help of troops from New

York or Rhode Island, he could end the rebellion.1

Subsequent events made it clear that he was wrong. New England was not to be subdued by six or seven thousand

regular troops. Nor is there any reason to think that a march into New England would have been safer than an

advance on Albany. Burgoyne's communications would have been exposed to the force on the Hudson instead of to

the New Hampshire militia; and the distances were as great, the country as difficult, the population as inveterate.

From Ticonderoga there were two routes to the Hudson. The one generally regarded as the easier was by Lake

George, from which there was a practicable waggon road to the Hudson where it became navigable at Fort Edward.

This route was eventually cleared and used for the army's supplies. But the retreating garrison of Ticonderoga had

been pursued up the narrow southern arm of Lake Champlain to Skenesborough, from which there was a long

forest trail to Fort Edward. Having started on this line Burgoyne held to it. The decision was much criticised; but

he reasoned that the enemy would probably have blocked the road from Fort George as effectively as they blocked

the road he took, and that by using the Skenesborough route he forced the Americans to abandon Fort George

without a fight. These reasons may have been valid. He did however employ a third argument, that a withdrawal

from Skenesborough to start again on the Lake George route would be discouraging. This contention was curiously

similar to Howe's reason for not entrenching at Germantown; and it is odd that two commanders whose troops'

morale was high should both have accepted unnecessary disadvantages for fear of damaging the spirit of their

men.2

1 Fonblanque, 2334, 256. His letter of 11 July to Germain (CO 42/36, f. 361) seems to show that he was in

fact perfectly ready to turn his whole force towards the Connecticut in spite of his orders; but finding the

enemy preparing to strengthen themselves on the Hudson, he would 'employ their terrors that way, and after

arriving at Albany it may not be too late to renew the alarm towards Connecticut.'

2 Fonblanque, 264, 267.

< previous page page_132 next page >