Mackesy P. The War for America, 1775-1783

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

page_73

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_73.html[1/17/2011 2:25:20 PM]

< previous page page_73 next page >

Page 73

Chapter IV

The Arrested Offensive

1

These Noble Heroes

The task in America cried out for men of stature. For when the Ministry at home had allocated the reinforcements

and expressed its general hopes for the campaign, it could exercise no further control. News from America ran

with the prevailing wind and at the most favourable might take a month. But a westerly passage from England with

the Cabinet's instructions very rarely took less than two months from office to office, and many despatches from

home took three or four months to reach their destination. Weather and enemy cruisers took their toll; but by far

the greatest cause of delay was the shortage of despatch ships. Forty Post Office packet-boats were lost during the

war.1 The generals were periodically accused of hoarding packet-boats in America, which they denied; but

whatever the real cause, no regular and frequent service could be maintained. If the Admiralty was asked to help, it

was quite capable of sitting on the despatches for weeks before it found a conveyance. The slowest recorded

transmission was probably that of the accumulated despatches which were sent out by the September packet of

1781. The packet was taken, and for some reason the duplicate copies sent out in a warship went astray. The

triplicates reached New York on 11 April 1782, six or seven months after they were written.2

The responsibility for bringing strategy to the battlefield therefore lay entirely on the commanders in the theatre.

Between January and March of each year Germain allocated the reinforcements and approved the plans.

1 Ellis, Post Office in the Eighteenth Century. 96.

2 A rough check of letters sent by Germain to Clinton on sixty-three days between May 1778 and Feb. 1781

yields the following passage times:

less than two months .....

6

days' letters

2 months . . . .....

12

'' "

23 months . . .....

28

" "

34 " . . .....

11

" "

45 " . . .....

4

" "

57 " . . .....

2

" "

(counting all the despatches sent by the packet of Sep. 1781 as one).

< previous page page_73 next page >

page_74

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_74.html[1/17/2011 2:25:20 PM]

< previous page page_74 next page >

Page 74

Thereafter he could do nothing to influence the course of events. His summer despatches were little more than a

running commentary of applause and disapproval. Conscious of their isolation from the source of political

direction, both Howe and Burgoyne had suggested in the previous summer the appointment of a viceroy with full

powers to co-ordinate operations. 'There is no possibility', Burgoyne had written, 'of carrying on a war so

complicated as this will be, at the distance we are from the fountain head, without these full powers being at

hand.'1 Such an office would have been as foreign to the constitution as was the Congress of the colonies, and

might, in acknowledging the unity of the rebellion, have implied the right of the colonies to negotiate in unison. By

appointing two brothers as General and Admiral, and vesting them jointly with the power of negotiation, the

Ministry may with reason have hoped to provide both sufficient authority and sufficient unity in the theatre. The

inclusion of Canada in a unified military command was out of the qestion as long as overland communications

were closed.

The history of the Howes' appointment was rather curious. The General, William, had had the imprudence to tell

his parliamentary constituents at Nottingham that he condemned the government's American policy and would not

accept a command there. But he had been looking for employment; and the offer, very lucrative and made perhaps

in a manner which was difficult to refuse, was evidently more than he could bear to turn down.2 His elder brother

Admiral Lord Howe, was in an equally ambiguous position. He was favourably disposed to the Americans; but he

wanted employment, and was bought by the Ministry for political reasons. He had served on the Board of

Admiralty under Sandwich and Egmont in the 'sixties, but had recently quarrelled with Sandwich over a sinecure.

Lord North had promised him the reversion of the Lieutenant-Generalcy of Marines on the death of Sir Charles

Saunders; and when it went instead to Sandwich's friend Sir Hugh Palliser, Howe was, like Admiral Keppel,

violently offended. If Horace Walpole can be trusted, the Ministry hastened to buy off his resentment with the

American command.3 It was a high price, for Howe made his own terms. Sandwich's friend Shuldham had just

reached America to replace Graves, and to save the Admiralty's face North suggested carving out a separate

command for him in the St Lawrence. But Howe would not hear of it, and Shuldham's supersession had to be

softened by the unusual dis-

1 Sackville, II, 9; G 1693.

2 Anderson, Command of the Howe Brothers, 479. For Burgoyne's account of the manner of his own

appointment at the same time, see Fonblanque, Burgoyne, 120.

3 But Germain's friend Sir John Irwin recorded that the appointment was due to pressure from Germain

(Hastings, III, 169).

< previous page page_74 next page >

page_75

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_75.html[1/17/2011 2:25:21 PM]

< previous page page_75 next page >

Page 75

tinction of a peerage. Over the terms of the Peace Commission Lord Howe also made difficulties, in opposition to

the tough line advocated by Germain. But though he went through the motions of preparing to resign, the

politicians guessed that in the last resort he would not refuse the command. This was not the way Chatham would

have appointed; but a weak Ministry could not take a strong line with politicians in uniform.1

The Howe brothers were courageous and popular leaders: tall, dark inarticulate men of proved tactical skill.

William Howe had done well on two continents in the Seven Years War. He had led the forlorn hope which scaled

the Heights of Abraham, and was a master of light infantry tactics. Both the brothers were regarded as moderate,

level-headed men for a delicate task, and tolerably well-disposed to the Ministry. It was said that Lord Howe had

not spoken to Germain since the St Malo expedition of 1758; but the brothers launched their American careers on

friendly terms with the American Secretary and possibly under his patronage. Before Germain entered the Cabinet,

Lord Howe had written acknowledging his 'particular goodness to my brother on his late appointment'. Germain

was warmly congratulated by General William when he took office, and again on his preparations for the

campaign; and Germain was equally warm in his approval of the General's operations.2 Though the Howes

certainly felt some sympathy for the Americans, they accepted the need to check America's drift from the colonial

system. Lord Howe wrote to his old acquaintance Benjamin Franklin of 'the necessity of preventing the trade from

passing into foreign channels'. He regarded Barrington's fear of military operations as pusillanimous; and the only

anxiety to which the brothers confessed before the opening of the campaign was that the effort might be too

small.3

Yet their taciturnity made them difficult to measure. In the House of Commons the General was no master of

argument; and Lord Howe's dark ambiguous speeches were scarcely comprehensible.4 They had no profound

knowledge of the American political scene. Their attitude to the struggle was somewhat ambivalent; and their

known professional abilities were those of tacticians. For the Admiral this was almost enough. He had only to

control the rebels' trade, protect British shipping, and support the army. The technical difficulties were

considerable; the strategic choices few. The General's task was more complex. He was to command the greatest

army

1 Anderson, 524; Sandwich, II, 201; G 1816, 1818, 1836.

2 CL, Germain, 22 July 1775, Lord Howe to Germain, and passim; Sackville, II, 11, 30. cf. Wykeham-Martin,

315. For their earlier bad relations, see Valentine, 39, 46: Walpole appears to be the only evidence.

3 Add. MSS. 34413, f. 56; CL, Germain, 29 July 1775.

4 Anderson, 7, 43; Wraxall, II, 288.

< previous page page_75 next page >

page_76

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_76.html[1/17/2011 2:25:21 PM]

< previous page page_76 next page >

Page 76

ever sent across the oceans, in a situation of deep political and military confusion. Colonel Stuart feared he would

be imprudent1, but the guess was wide of the mark. For as Clausewitz was to observe, the boldest subordinate

rarely makes a resolute chief. The highest levels of command press harder on the intellect; and with time to ponder,

doubt and confusion creep in. In putting forward his plans of campaign in the autumn of 1775 Howe had written

that it was 'of greater compass than he feels himself equal to direct'. Would he rise to the challenge; or had he

already reached the ceiling of his ability when he was entrusted with supreme command?

Of Howe, at the outset, Germain and his colleagues seem to have felt no doubts. With Carleton in Canada it was

different. The recall of Gage had made Carleton the senior General in America; and at first he had been intended

to command all the forces on the continent if his own troops should form a junction with the army on the Atlantic

seaboard. But for reasons buried in their past2 Germain distrusted him. 'I take the General to be one of those men

who see affairs in the most unfavourable light', he wrote to Sandwich on learning of the American invasion of

Canada; 'and yet he has the reputation of a resolute and persevering officer.'3

Carleton was ruled out as supreme commander when the Howe brothers were appointed sole Peace

Commissioners; and Germain did not intend him to command the advance from Canada in person. Clinton would

have been sent from Boston to act as his field commander, with instructions to place himself under Howe's orders

when the two armies joined; but Clinton had already been ordered south to command the Charleston expedition, so

instead John Burgoyne was sent out with the reinforcements as second-in-command in Canada.4 When he arrived,

however, he found operations already begun under Carleton's direct control; and in the absence of an order from

home to relinquish them to his subordinate, the Governor continued to command his army in person.

As a Governor Carleton had many admirable qualities. His financial integrity, humanity and conscientiousness

were beyond dispute; and his breadth of vision had created the Quebec Act which made it possible to fit the

French-speaking Catholic Canadians into the structure of the empire. Yet a temper which could bear no criticism

led him to arbitrary removals of councillors and judges who spoke out against his views; and his largeness

1 Wortley, 73.

2 Horace Walpole conjectured from Carleton's friendship with the Duke of Richmond that Germain knew he

was unfavourable to him on the Minden question.

3 Sandwich, I, 86.

4 CL, Germain, 1 Feb. 1776 to Howe.

< previous page page_76 next page >

page_77

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_77.html[1/17/2011 2:25:22 PM]

< previous page page_77 next page >

Page 77

of vision was accompanied by a flawed judgment. In administering the Quebec Act he had committed two

important errors: he failed to realise that the seigneurial régime in Canada was an empty shell, since seigneurs

competing for tenants were in no position to exact tenurial obligations; and contrary to the British government's

intentions he withheld from the English-speaking minority the protection of English law in civil suits. The result

was that he greatly over-estimated the loyalty of the population and the help which the army could expect from the

machinery of the feudal régime. In this fool's paradise he had sent two of his four regiments to Boston in response

to Gage's appeal in 1774, and had allowed the government to believe that Canada would defend itself and provide a

well-served military base against the Revolution. These dreams were shattered by the events of 17756.

As a commander in the field Carleton's abilities have also been rated high; but the evidence is slender, for by 1777

he was displaced from the control of operations, and coming home in 1778 he returned to America only to

superintend the final evacuation. His military reputation therefore rests on his defence of Quebec in the first winter

of the war - which was no very severe test once the first shock had been met - and on the subsequent advance to

the frontier; and on the latter the evidence is not as unequivocal as his admirers claim.

The appointments of Howe and Carleton were confirmed in the spring by the revocation of Gage's commission as

Commander-in-Chief, though he was left the now sinecure Governorship of Massachusetts. Howe and Carleton

were promoted to the local rank of General, and Clinton, Burgoyne, Cornwallis and Percy became local

Lieutenant-Generals. Germain let it be known that the King would employ no General senior to them in the

rebellious colonies, thus granting to the officers who had come forward promptly at the outset a vested interest in

the expanding theatre. They had a great opportunity; but not everyone believed that they would rise to it. A

captious but able Colonel at Boston had complained during the winter that the army had the most ordinary men to

command it: 'I hope to God they will send us some Generals worthy the command of a British army', he wrote.1

Their tactical instrument, at any rate, was superb. British infantry in battle were among the best in the world, and

the artillery among the most efficient. In open country or a well-planned assault they were invariably successful.

Their trust was not in marksmanship, but in the close-order volley and the bayonet charge. 'It will be our glory and

preservation to storm where possible', ran Burgoyne's orders to his troops. Howe's first campaign was to

1 Sandwich, I, 119; CL, Germain, 1 Feb. 1776 to Howe; Gage, II, 207; Wortley, 74.

< previous page page_77 next page >

page_78

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_78.html[1/17/2011 2:25:22 PM]

< previous page page_78 next page >

Page 78

prove the virtues of the army and its tactics. The Americans hated the bayonet, which they resented just as the

British resented the sniping of officers by rebel sharp-shooters; and they respected the close order drill of the

German plains enough to learn it from European instructors.

Yet in many ways the British army was not suited to American service at the beginning of the war. It marched

slowly and with too much baggage. A battalion embarking for foreign service was allowed sixty women and eighty

tons of baggage: a General and his staff might take as much for themselves. A German officer writing of the Seven

Years War censured the officers' love of comfort; yet in America it was the German troops who showed themselves

least ready to relinquish their baggage and indulgences, as both Howe and Burgoyne were to complain in their

separate theatres. All, whether British or German, were professional eighteenth-century troops performing one

more duty. Campaigning for years in a harsh and distant country, they could not be expected to forego their

comforts as the short-service American armies and the inflamed militiamen would do. Nor could their commanders

afford to let them freeze or starve: they were not expendable. A British army needed warm clothing, tents, and

cooking equipment.

The tactics, too, so effective in open country and against regular entrenchments, were not good enough in forests

and enclosures. The lesson of Braddock and the Indian Wars might never have been learnt, for all that was

remembered of light infantry tactics by Gage's troops when the war began. After Braddock's defeat in 1755 light

infantry had been trained to protect the main body from ambush and sniping. But as Germain recognised at once,1

the losses on the retreat from Concord had the same cause as Braddock's disaster: against an enemy who refused to

stand and face them, the troops kept together and volleyed. If the Boston garrison had kept up its light infantry

training, the embattled farmers would have been brushed off with ease.2 But the art of open-order fighting had to

be relearnt, and Howe was the man to brace the army's discipline and teach them. One of his first steps was to

group the regimental light companies into separate battalions, as Wolfe and Amherst had done. As the war

progressed, the infantry as a whole learnt to hold their own in extended order in the woods. In most tactical

situations their discipline and experience told against the individual initiative, marksmanship and speed of the

Americans. Their slowness lost them some opportunities. But the two great defeats of the war at Saratoga and

Yorktown were strategic rather than tactical. The soldiers so curiously crimped and scraped together bore their

burden nobly.

1 Sackville, II, 2.

2 So Fuller argues in his British Light Infantry in the Eighteenth Century, 125.

< previous page page_78 next page >

page_79

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_79.html[1/17/2011 2:25:22 PM]

< previous page page_79 next page >

Page 79

2

The Winter at Quebec and Boston

It was to Quebec that the Minister looked anxiously for the first news of the year. The February report of a rebel

repulse was true; but it was an anxious and critical winter for Canada. When Montgomery's Americans advanced

2,000 strong from Ticonderoga in September 1775, Carleton had only 800 seasoned troops to oppose them; and in

spite of the support of the seigneurs and the Catholic heirarchy, the Canadians had been slow to come forward to

his help. Carleton concentrated most of his little force in front of Montreal, and threw the bulk of the men into Fort

St John's in the path of the enemy. Major Preston defended his wooden ramparts with gallantry; and without

trained men or cannon Montgomery was baffled. Probing forward with a small detachment in the rear of the fort,

he attempted a coup de main against Montreal and was repulsed. But Fort Chambly surrendered to the rebels,

giving them the equipment to press the siege of St John's. On 2 November it surrendered after a resistance of fifty-

five days, and Montreal was abandoned.

A two-months' delay had been imposed on the rebels, and winter was closing in on them. But in the approaches to

Montreal Carleton had sacrificed most of his seasoned troops. Quebec was almost defenceless when, a few days

after the surrender of St John's, a second and totally unexpected American force burst from the wilderness of

Maine on to the banks of the St Lawrence opposite the city. Only the river stood between the survivors of Benedict

Arnold's heroic march and the helpless capital. But while they prepared to cross, the news of their coming travelled

up the river to Sorel. There Colonel Allan Maclean was forming a regiment of highland immigrants. He moved at

once by forced marches, and entered the city with nearly 400 levies as Arnold was scaling the Heights of Abraham.

Maclean's decisive march made him the saviour of British Canada.

Besides these recruits there were about 100 British regulars in the city; and with seamen, marines and armed

inhabitants, Maclean and the Lieutenant-Governor collected a motley garrison of 1,300 men. When Carleton

arrived in disguise from Montreal, he found enough men to hold Arnold in check. Even when Montgomery

appeared early in December, the 1,600 Americans were baffled. A siege by regular approaches was impossible, for

their light cannon were overwhelmed by the artillery on the ramparts. Starvation might have reduced the garrison

in due time, but the American enlistments were about to expire, and Montgomery was driven to the desperate

expedient of a coup de main. In the snow and darkness of 30 December the Americans stormed and were repulsed.

Arnold was seriously wounded, and among the dead was Montgomery.

This was the only attempt to storm Quebec. But reinforcements enabled

< previous page page_79 next page >

page_80

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_80.html[1/17/2011 2:25:23 PM]

< previous page page_80 next page >

Page 80

the wounded Arnold to maintain a blockade, though his force was drained by smallpox, expiring enlistments and

desertion. The garrison's provisions shrank; but winter was dissolving, and the vanguard of Germain's relief was on

the way. On 6 May, three days short of sixteen years since the Lowestoft had raised the French siege in 1760, the

Isis and Surprise burst through the ice. Canada had been snatched from the ruin of the American Empire, and the

bridgehead saved for the army which was coming.

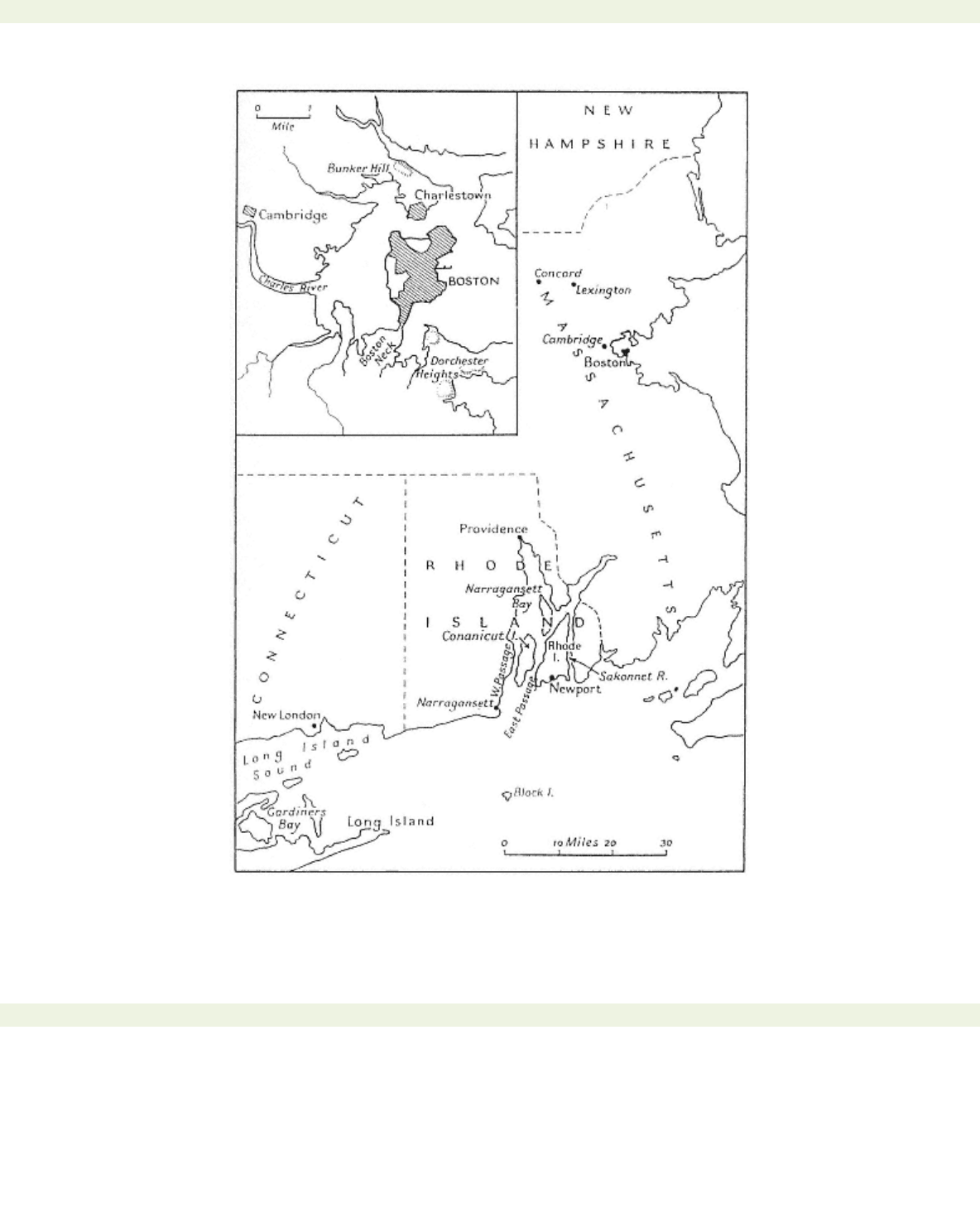

At Boston General Howe had endured a winter as trying as Carleton's. Since Bunker Hill he had been closely beset

by Washington, who had arrived to assume the command of the rebels. The enemy had great difficulties of their

own. They were short of powder, and their troops were continually melting away like Montgomery's at Quebec.

But they were strongly entrenched, and backed by the armed population. Howe, deprived of intelligence, saw little

to be gained by a sortie and perhaps everything to lose; for he had less than 9,000 men of all arms to hold the long

circuit of the city whose fortifications an officer had judged to need two years' work and a garrison of 20,000

men.1 Supplies were very short, and the ships expected from England did not appear. In the New Year an officer

sailed for the West Indies in search of the missing victuallers, and found twenty-six vessels which had been blown

off their course to Boston lying at Antigua in various states of damage and loss. By March there was less than three

weeks' supply of meat in Boston. Yet though Howe was anxious to evacuate the town and be early in the field at

New York, only the arrival of transports from Europe would make an orderly embarcation possible.

The impasse was broken by the enemy. With characteristic energy the artillery captured in Ticonderoga had been

dragged across the snow-bound hills of New England; and on the night of 4 March Washington occupied

Dorchester Heights and threw up batteries to command the harbour. The ingenuity which entrenched the frost-

hardened peninsula in a single night deserved success. Howe had either to retake the heights or lose Boston. An

assault planned for the night of the 5th was frustrated by a heavy storm; and the Americans pushed their lines

forward till they flanked the British lines on Boston Neck. Howe had to leave while he could. Into seventy-

eightships of an average burthen of 250 tons were crammed troops, loyal inhabitants, stores and horses. Much had

to be sacrificed: a hundred pieces of ordnance, a hundred irreplacable trucks and waggons, eighty horses, and large

quantities of barrack stores and forage. On 17 March, St Patrick's Day, the British army left Boston for ever.2

1 Wortley, 70.

2 The happy coincidence with the feast of the Irish saint preserves Evacuation Day among the numerous public

holidays of Massachusetts.

< previous page page_80 next page >

page_81

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_81.html[1/17/2011 2:25:23 PM]

< previous page page_81 next page >

Page 81

BOSTON AND RHODE ISLAND

6

< previous page page_81 next page >

page_82

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_82.html[1/17/2011 2:25:24 PM]

< previous page page_82 next page >

Page 82

3

The Concentration off New York

The evacuationof Boston might have enabled Howe to establish his new base without trouble by forestalling

Washington at New York. But the confusion of troops and stores in the overcrowded transports made immediate

operations unthinkable. The spring of 1776 should have seen Carleton on the frontier of Canada, thundering at the

gates of New England; while Howe, after a winter comfortably entrenched on Manhattan, prepared to advance and

meet him. Instead, Carleton had been swept back as far as Quebec and prevented from collecting the material

needed for his advance; while Howe, after a winter chained in Boston, was steering for Halifax. No tactical landing

could be attempted till the ships had been reloaded at a friendly port and provisions collected for the campaign.1

Howe was clear that there was no hope of conciliating the Americans till their armies had been roughly handled.

He foresaw some difficulty in doing so; for with the whole country at their disposal they could easily retire a few

miles back from the navigable rivers, and Howe with his shortage of land transport would be unable to follow

them.2 This difficulty, aggravated by the loss of waggons at Boston, was never to be fully overcome. In spite of

the three hundred waggons shipped from England that spring, transport was always short. A few of the heavy four-

horse waggons which supplied the army in the field were built in the army's waggon yard at New York. But about

two-thirds of the army's vehicles were hired in America by the day or month. The shortage was a fertile source of

corruption. Commissaries hired their own waggons to themselves; and the officers of the Quartermaster-Gerneral's

department were computed at the end of the war to have put more than £400,000 into their own pockets from the

contracts they allotted in the course of five years. Nevertheless it was the vulnerability of communications as much

as the shortage of waggons in an extensive and hostile country which hampered the army's freedom of movement.

It was the risk of having convoys attacked which Charles Stuart two years later said had 'absolutely prevented us

this whole war from going fifteen miles from a navigable river'.3

In spite of the difficulty which he foresaw, Howe was in a hurry to leave Halifax. For he hoped that elation at the

recovery of Boston would tempt the Americans to offer the battle which he believed was the shortest way to end

the war; and the health and discipline of his troops made him sure of victory. He still hoped to join Carleton in the

Hudson valley before the year was out. By early May he had collected enough additional tonnage to

1 Howe's Orderly Book, 319; Anderson, 105.

2 Sackville, II, 30.

3 Curtis, 136, 1445; Clode, I, 136; Wortley, 113.

< previous page page_82 next page >