Mackesy P. The War for America, 1775-1783

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

page_83

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_83.html[1/17/2011 2:25:24 PM]

< previous page page_83 next page >

Page 83

embark his force in tactical order. But he still lacked provisions. Only one of the numerous Treasury victuallers

which had sailed between August and November had yet arrived; and on 7 May there was less than a fortnight's

meat. June came in before the army could move; but at length it sailed 9,000 strong on 11 June for New York.1

The entrance to New York harbour is guarded by a narrow passage between Staten Island and the western end of

Long Island. Howe's first object was to open the passage for shipping by securing these points. On 29 June the

convoy reached Sandy Hook in the outer approaches to New York, and four days later the troops landed on Staten

Island and secured their first objective. But here the operation halted, for Howe had changed his mind about

hastening on the battle, and resolved to wait for reinforcements before he tackled Long Island, where the

Americans had had time to fortify the heights of Brooklyn. For seven weeks the troops idly watched the summer

gliding away. Not till 22 August did the assault begin.

Even before he left Halifax the General had begun to hesitate. He had written to Germain that in his early

operations he would bear the coming reinforcements in mind, and risk no difficult attacks without them. As it

happened, a letter was then on its way from the Secretary of State which expressed a similar line of thought: it

applauded his expressed intention to make an early attack on New York, but hoped that 'as such large

reinforcements are going to you, I wish they may arrive before the time of carrying it into execution'. This was not

an instruction to wait but a hope of timely help; and since it only reached Howe when he had been twenty-four

days on Staten Island, it can have had no influence on his decision, though it may have encouraged him to stick to

it.2

From Howe's caution some of his contemporaries deduced that he had never shaken off the effect of his losses at

Bunker Hill. But this is a highly speculative subject. The whole demoralising experience of the months in Boston

continued to oppress the army's command. Sir William Howe's first introduction to the loyalists as a frightened

handful of New England refugees must have prejudiced him permanently, and made him disinclined to encourage

them in areas where they were thicker on the ground; and the winter shortages in Boston may have had a lasting

influence on his conduct of operations.3 Yet whatever the particular experiences which may have influenced him,

the core of his thinking concerned the conservation of his force. Even when enough troops reached him he still

waited for the camp

1 CO 5/93, pp. 135, 153; Sackville, II, 32; Royal Institution, I, 46.

2 Sackville, II, 334; CO 5/93, f. 119.

3 These influences are suggested respectively by Nelson (p. 139) and by Anderson (pp. 71, 97).

< previous page page_83 next page >

page_84

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_84.html[1/17/2011 2:25:25 PM]

< previous page page_84 next page >

Page 84

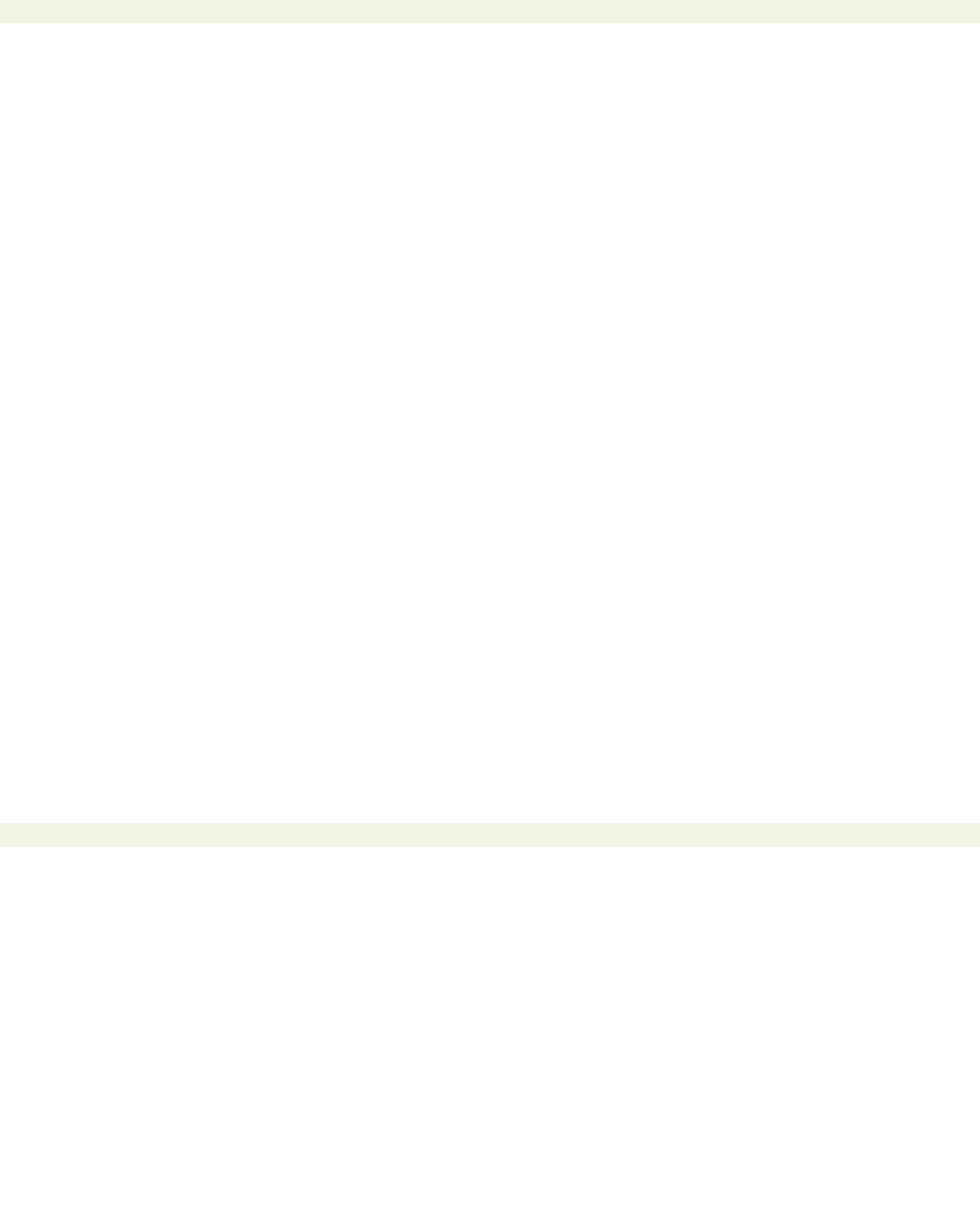

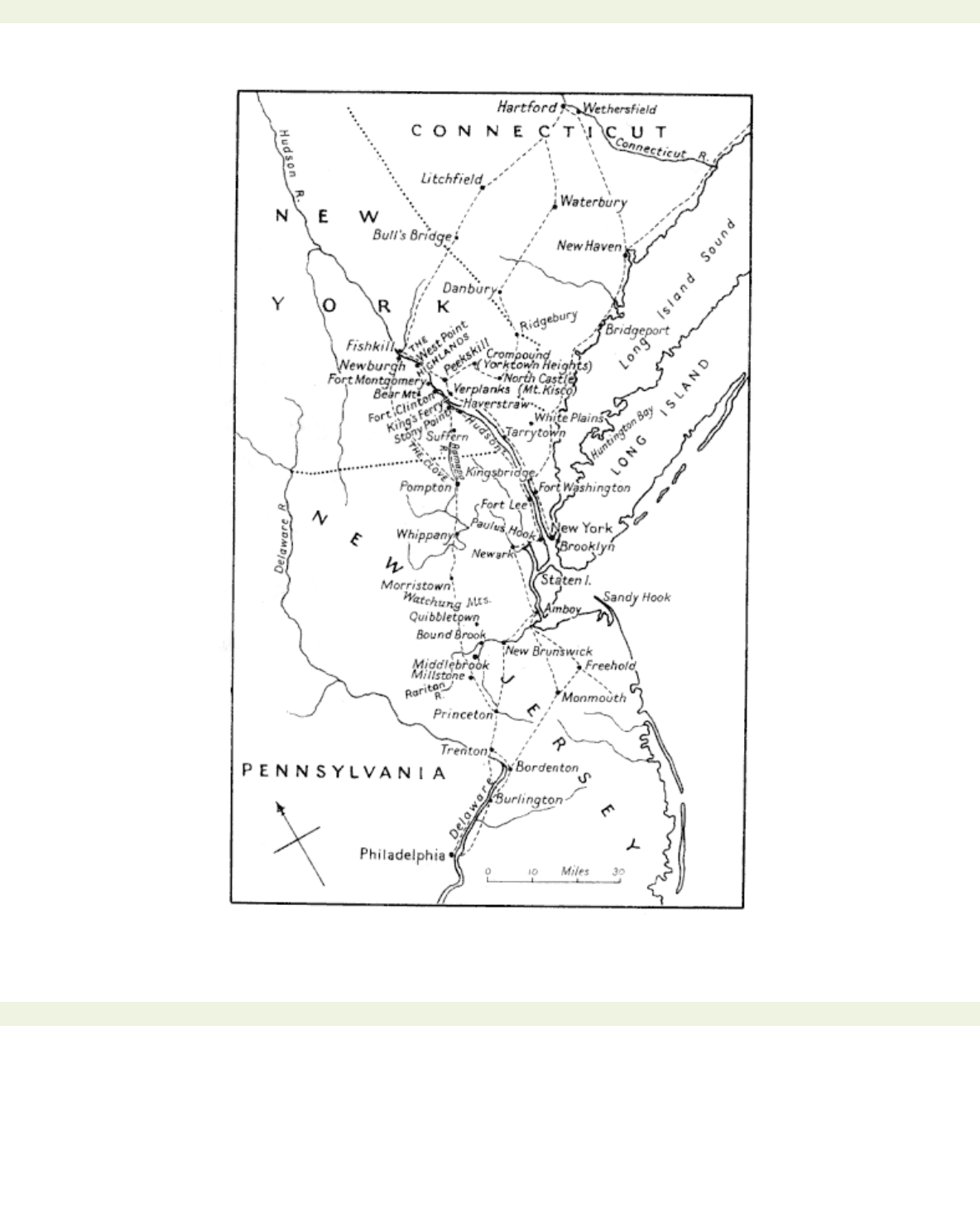

THE NEW YORK AREA

< previous page page_84 next page >

page_85

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_85.html[1/17/2011 2:25:25 PM]

< previous page page_85 next page >

Page 85

equipment. To take the field without camp kettles would have risked the health of his men; and these, as he

explained, were the irreplacable 'stock on which the national forces in America must in future be grafted'.1 This

thought had been in many minds since the rebellion broke out: in Lord Percy's this summer when he wrote that 'our

army is so small that we cannot even afford a victory'; in the Adjutant-General's when he had feared that the army

would be 'destroyed by damned driblets' if no settled plan of operations was fixed; and far off in Minorca in

General Murray's when he rejoiced that Howe had not risked a general engagement. 'The fate of battles at the best

are precarious. When Burgoyne gets over the Lakes, and Sir John Johnstone [sic] penetrates with his Indians, Sir

William Howe's detachments co-operating with them, must open the eyes of the deluded, unshackle the

constrained, and accomplish your most sanguine wishes without much bloodshed.' For as he had written to Lord

Barrington in the summer of 1775, the Americans' plan ought to be to lose a battle every week, till the British army

was reduced to nothing: 'it may be discovered that our troops are not invincible, they certainly are not immortal'.2

Howe's situation, far from home in command of his country's only army, was a characteristic British one.

Wellington in the Peninsula was to operate under the constant restraint of knowing that his army was England's

last, and that one serious defeat would be the end of his campaigns.

If all had gone as Germain had planned, Howe's reinforcements should have reached him much earlier. But the

transport shortage, aggravated by the winter frosts and the stringent priority of saving Canada, had delayed the

embarkations. The first to sail had been the Highlanders at the end of April: late, yet in another sense too soon, for

a few days later, when it was too late to change their destination, news arrived of the evacuation of Boston eight

weeks earlier. Through some neglect by the navy, no warships were left off Boston to meet them, and several

transports fell a prey to rebel cruisers. The remainder were dropping in early in July; and on the 12th Lord Howe

arrived in the Eagle to command the fleet, after a voyage of two months by way of Halifax. Hotham's convoy with

the Guards and Hessians sailed from England late enough to be diverted from Boston. The Admiralty had intended

to send them to Halifax, but on Germain's suggestion the Commodore had been given latitude to seek the army

where he was most likely to find it.3

One further contingent remains to be accounted for: the regiments

1 CO 5/93, p. 228.

2 Anderson, 90; Sackville, I, 371; CL, Germain, enclosure in Murray's to Germain of 27 Aug. 1776.

3 Adm. 2/1333, f. 39; G 1859; Adm. 1/310, Hotham's of 5 May 1776.

< previous page page_85 next page >

page_86

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_86.html[1/17/2011 2:25:26 PM]

< previous page page_86 next page >

Page 86

borrowed from Howe's reinforcements to recover South Carolina. By now they should have completed their

mission and joined the main army; but as he had feared, they were still absent from his order of battle. Retarded by

its many misfortunes, the expedition had not reached Cape Fear till 2 May. Clinton had been waiting there for eight

weeks to assume command; and in that time the situation in the southern colonies had changed rapidly for the

worse. The loyalists of North Carolina had risen in February, when the British troops should have been at hand to

support them, only to be defeated and scattered, and their leaders imprisoned. In South Carolina, where the back

country was even more hostile to the Revolution, the loyalists had been defeated in November, through lack of

leadership, by an inferior force of rebel militia; and Clinton at first saw little point in taking Charleston, a difficult

operation in itself, since the loyalist strength was in the interior and his amphibious force could not move far from

its transports. Georgia was ruled out by the approach of the hot weather. In these circumstances Clinton's first

instinct was to call off the operation and move northwards to look for an opening in the Chesapeake till he was

needed by Howe.

The despatch which was on its way from Germain gave him the latitude to do this very thing. Unfortunately

Clinton had second thoughts before its arrival. Learning that Howe did not expect him in time for the opening of

the northern operations, and hoping to achieve some sort of diversion in the south, Clinton changed his mind and

decided to attack Sullivan's Island in the approaches to Charleston, where the rebel fortifications were still

unfinished. It was planned as a probing attack, with no follow-through unless rapid success seemed certain, so he

was not deflected from his purpose by the arrival of Germain's permission to abandon the whole enterprise.1 On 28

June the squadron engaged the batteries of Fort Moultrie, and the troops landed. But the tidal shoals where they

disembarked proved to be unfordable; and after ten hours of costly and ineffective bombardment the fleet retired,

with 200 casualties and the loss of a frigate. Three more weeks were wasted with no clear purpose before the

expedition sailed to join Howe at the end of July. Germain's chagrin at the affair can be understood.2

On 1 August Clinton arrived at Staten Island from Charleston; and on the 12th Hotham brought in the Guards and

Hessians. Howe had an army of 25,000 men, 'for its numbers one of the finest that ever was seen'.3 More

1 CO 5/93, pp. 459, 463, 473.

2 CL, Germain, 22 Aug., Germain to Burgoyne. Lord Huntingdon told Hutchinson that Clinton had been

constantly sea-sick for two months before the attack on Charleston. If this was true, it is not the only occasion

on which sea-sickness has caused a British operation to miscarry (Hutchinson, Diaries, II, 177).

3 Rutland, III, 6.

< previous page page_86 next page >

page_87

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_87.html[1/17/2011 2:25:26 PM]

< previous page page_87 next page >

Page 87

important to Howe was the arrival of the camp equipment. At last he was satisfied and ready to act. But most of

the summer had been wasted, and he no longer expected the campaign to be decisive. He hoped for no more than

the capture of Rhode Island and New York, and even Rhode Island would have to wait. The enemy had had time

to concentrate their army at New York, and against it Howe would deploy his whole strength.1

4

The Clearing of New York

During the long pause at Staten Island, the Howes had made their first overture as Peace Commissioners. They

published their powers in a Proclamation which promised pardon and a fair consideration of measures to re-

establish lawful government. It was sent to Washington with a covering letter; but since it was addressed to him as

a private person and not an American General he refused to receive it. The bearer retaliated by refusing him a

copy; and Washington 'expressed some concern at the idea of all communication being at an end, as he was fully

convinced how much we had already suffered for want of that free intercourse subsisting among all civilised

nations though at war'. The sentiment marks the reluctance even of the rebels to fight without restraints. But

whatever Washington's views about protocol, the overture was vain. Ten days earlier the Congress at Philadelphia

had approved the Declaration of Independence; and now only victory in battle could pave the way to negotiation.2

On 22 August Howe made his landing unopposed on Long Island. The landing craft from England put down 6,000

men on the beaches in the first wave. Commodore Hotham organised the naval side, and his experience was later to

be valuable against the French. It was a smooth operation which spoke well for the commanders, troops and

equipment.

Washington's plan was to hold the fortified heights of Brooklyn. He took up a covering position to the eastward

and prepared for his first battle in the field. His army had good material; but it was raw, unformed and badly

officered. At Bunker Hill and Boston it had learnt to rely too much on entrenching. 'The practice we have hitherto

been in, of ditching round our enemies, will not always do', John Adams foretold.3 Washington himself was misled

by past success. At Bunker Hill the British had underrated the rebels and tried to teach them the sharp lesson of a

frontal attack, and he assumed that they would not try to manoeuvre now. But while General Putnam walked up

and down repeating his Bunker Hill injunction not to

1 Sackville, II, 38; CO 5/93, p. 228.

2 Royal Institution, I, 50; Anderson, 1535.

3 Freeman, IV, 1412.

< previous page page_87 next page >

page_88

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_88.html[1/17/2011 2:25:27 PM]

< previous page page_88 next page >

Page 88

fire 'until you see the whites of their eyes', the Americans were surprised by a swift and undetected turning

movement which sent them flying from their positions.

Howe had begun the game like a skilled tactician. He had inflicted 2,000 casualties at the cost of 300, and driven

the Americans back against the East River. He had only to storm the Brooklyn lines to win his decisive victory.

The troops were on the point of storming the main redoubt, and Howe thought it would certainly have fallen. But

he 'would not risk the loss that might have been sustained in the assault'. His victorious soldiers were stopped in

full cry, and set down to attack by siegecraft a ditch three miles long and three or four feet deep, which General

Robertson said would not have stopped a foxhunter.1 It is a puzzling episode, never satisfactorily explained.

Stedman and others have suggested that Howe was reluctant to shed American blood; but all the evidence shows

that it was British lives he cared for. On the other hand he was soon to prove his willingness to storm

entrenchments at Fort Washington. His later statement at the parliamentary enquiry suggests that he thought there

was a second shorter set of lines in the rear of the one he faced, to cover the enemy's embarkation and rob the

British of their reward for storming. The lines were evidently difficult to reconnoitre, and without full knowledge

of the situation one must be cautious of criticising his decision, though many later episodes repeated the pattern.

But whatever the truth, the decision was a misfortune. Ground was broken, and regular approaches begun. But

while the north wind still barred the East River to British warships, Washington snatched his army away by a swift

and silent evacuation.2

Thus victory eluded Howe; and on 2 September he reiterated that a second campaign would be needed to kill the

rebellion. Yet there was still reason to hope for victory by the end of the year. The enemy had been outmanoeuvred

and thrown into confusion; British and Hessian morale was high; and the reception on Long Island was

encouraging. This was the real key to success: 'I never had an idea of subduing the Americans', General Robertson

was to say; 'I meant to assist the good Americans to subdue the bad.' And the attitude of Long Island promised

success. 'The inhabitants received us with the greatest joy', wrote a field officer, 'seeing well the difference between

anarchy and a mild regular government.' There was a general belief that the raw rebel army would break up in

adversity, and General Lord Percy drew a conclusion: 'Everything seems to be over with them, and I flatter

1 Hutchinson Diary, II, 260. cf. Mackenzie (89), who wrote two months later that though many thought

Howe had missed an opportunity at Brooklyn, his cautious conduct in not risking a check in the first battle

was generally approved.

2 Anderson, 13440; Howe's Narrative, 5, 64.

< previous page page_88 next page >

page_89

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_89.html[1/17/2011 2:25:27 PM]

< previous page page_89 next page >

Page 89

myself now that this campaign will put a total end to the war.'1 Perhaps this hope had been the explanation of

Howe's conduct before the Brooklyn lines. With the rebel army apparently in his grasp, and the civil population on

his side, what need to shed vain blood in an unprepared assault?

While the next assault was prepared, a second and more hopeful attempt was made to negotiate. General Sullivan

had been taken on Long Island, and was used as an intermediary. He went to Philadelphia, carrying the impression

that the Commissioners had wider powers than Congress believed; and an embassy from Congress, which included

Lord Howe's old friend Franklin, met the Commissioners on Staten Island on 11 September. But the meeting

confirmed their first impression, that the Howes could not discuss independence or allow Congress to treat on

behalf of the colonies; and they replied that America would consider nothing less. Even now military success had

not ripened the situation as Germain had hoped.2

In the meantime seventeen golden days sped by. From 29 August, when Washington evacuated Brooklyn, till 15

September, the army made no move. Howe always insisted that the time had been spent in necessary preparations;

and indeed he was mounting the most difficult of all operations, an opposed landing. He had to cross the wide East

River and land a force on the Manhattan shore. The landing craft had first to move round the end of Long Island

and up the East River under the enemy's batteries. To stem the strong current a north-flowing tide was needed; to

pass the batteries a full night's darkness. The first boats made the passage on 3 September; but conditions were not

right again till the 12th or 13th.3 On the morning of the 15th eighty British guns began to roar; and about one

o'clock the first wave of assault craft burst through the drifting smoke and disgorged their infantry on the

Manhattan shore above New York.

The defence had been deceived. Only a thin line of musketmen behind a breastwork guarded the beach at Kip's

Bay, and their supports would not come up under the warships' fire. They broke and ran in disgraceful panic, with

Washington raging vainly to check them. Clinton commanded the first wave; and if he could have thrust two miles

across Manhattan to the Hudson, several thousand Americans in New York would have been cut off. But he had no

artillery, his orders were to hold a bridgehead for the second wave, and he stood fast on high ground to cover the

landing place. Later he felt that a chance had perhaps been missed, though Lord Rawdon thought otherwise. More

curious, however, is a staff officer's journal which records that the

1 Wortley, 82; Hastings, III, 183; Wykeham-Martin, 315; Anderson, 1456

2 Anderson, 15560.

3 This was Anderson's contention. But Mr Ira Gruber of Duke University informs me that he believes the boats

were moving in the intervening period.

< previous page page_89 next page >

page_90

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_90.html[1/17/2011 2:25:28 PM]

< previous page page_90 next page >

Page 90

escape route was still left open by the dispositions for the night, when Howe rejected his advice to post troops

across the road by the Hudson. But Howe he wrote, was 'slow, and not inclined to attend to whatever may be

considered as advice, and seemed more intent upon looking out for comfortable quarters for himself . . .'1

The landing had been a brilliant success. But before the assault Clinton had shown the misgivings which haunted

the British command. He foretold strong resistance and a possible reverse, and later maintained that only the

American blunder about the British plan had enabled him to succeed. 'My advice has ever been to avoid even the

possibility of a check', he had written that morning. 'We live by victory.'2 The British superiority was moral, not

numerical. Hitherto the Americans had fled before them; raw men, whose military spirit, far from being broken,

had not yet been created. In normal warfare risks are justified to exploit success. But the Americans had the

resilience of innocence. Reverses quickly intimidated them; but the slightest run of success might transform them

into an army. This was indicated the day after the landing. Washington had drawn away to the north and occupied

a strong position on Harlem Heights. Two light infantry battalions supported by the Black Watch pressed

impetuously forward into a disadvantageous action in front of the advanced posts, and were quickly withdrawn by

Clinton on instruction from Howe. To the British it was an outpost skirmish; but the Americans had seen the

redcoats' backs, and thought they had won a major success.

Howe entered New York unopposed, and took possession of sixty-seven guns and much abandoned equipment.

Then there was another lengthy pause of four weeks. To the north Washington's flanks rested firmly on the Hudson

and the Harlem Creek. Howe spent his time in consolidating a base at New York, necessary if his assumption was

correct that there would be another campaign. A line of redoubts was formed across Manhattan, and a post at

Paulus Hook on the Jersey shore to make the harbour safe. This achieved, the army was free to manoeuvre. The

reception at New York had been disappointing, and Howe regarded further progress that year as doubtful. He

intended, however, to make a push. His aim was to threaten Washington's communications with Connecticut by an

amphibious movement, and manoeuvre him out of his Harlem position. But the tactical requirements of the army

and navy diverged, and there was much discussion before a plan was agreed. At last it was settled that a landing

should be made on an isthmus called Throg's Neck in the East River behind the American lines. The boats,

skilfully

1 Anderson, 16979; Hastings, III, 184; Mackenzie, 4950.

2 Willcox (ed.), American Rebellion, 46, n. 12. See a similar sentiment in Hastings, III, 186.

< previous page page_90 next page >

page_91

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_91.html[1/17/2011 2:25:28 PM]

< previous page page_91 next page >

Page 91

manoeuvred by the navy, moved through Hell's Gate in a dense fog and the landing was made. But failing to

surprise the Americans and seize the exit from the Neck, the troops were re-embarked and landed again a mile to

the northward, on which they thrust six miles inland to New Rochelle. There had never been much doubt that

Washington could slip away, but the aim of the operation was achieved. The rebels were forced out of their

entrenchments, and once more the armies were in the open field.

Washington, however, had learnt his lesson on Long Island. He had had enough of pitched battles for the moment:

'We should on all occasions avoid a general action, or put (sic) anything to the risk, unless compelled by a

necessity into which we ought never to be drawn'.1 This resolution, flexibly interpreted, became the foundation of

his strategy. It did nevertheless present him with a difficult choice. He could slip away into the mountains higher

up the Hudson, and be safe for a considerable time from pursuit. But he wished also to prevent a penetration of the

lower Hudson, in order to protect his lateral communications between Connecticut and New Jersey. He had

blocked the river at the northern end of Manhattan with a line of sunken hulks, commanded by the fire of Fort Lee

on the Jersey shore and Fort Washington on Manhattan. He had left garrisons to hold them when he retreated, and

took up a position at White Plains to remain in supporting distance. His flanks were secured by a river and a

marsh, and his numbers were about equal to Howe's. Howe promptly seized a height which dominated the

American right flank. But instead of pressing his success at once, he began to construct batteries which would

sweep the American position, and prepared for a general assault on 31 October. Rain postponed the attack for

twenty-four hours, and during the night Washington was able to evacuate his position and slip away to a stronger

one in his rear. Without accurate maps, Howe had to feel his way into the country to the north. He was convinced

that Washington did not intend to stand and fight, and that there was no point in continuing to push him

northwards. On the night of 4 November he decamped and fell back south-west to the Hudson. And on the 16th he

stormed Fort Washington.

When the British army marched away from his front, Washington had divided his force to meet the various

dangers which its movement suggested. He left 7,000 men under Lee in his present area; sent 5,000 into New

Jersey to guard against a thrust at Philadelphia; and posted 4,000 up the Hudson at Peekskill to guard the entrance

to the Highlands. This dispersion meant weakness everywhere; yet 3,000 men still lay locked up in Fort

Washington, at the gates of New York. Between these four packets of troops lay the British army. Washington

considered abandoning Fort Washington. Its usefulness was in doubt, for British frigates had forced the barrier of

hulks

1 Freeman, IV, 217.

< previous page page_91 next page >

page_92

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_92.html[1/17/2011 2:25:29 PM]

< previous page page_92 next page >

Page 92

THE LOWER HUDSON VALLEY AND NEW JERSEY

< previous page page_92 next page >