Lima J.J.Pedroso, de (ed.). Nuclear Medicine Physics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

178 Nuclear Medicine Physics

f (x, y, z) along that direction, that is,

direction i

(γ counts) ∝

direction i

f (x, y, z) dr

direction i

. (5.41)

Using the notation introduced in the previous section (see, e.g., Figure 5.27),

this line-integral approximation [42] can be expressed in terms of the parallel

projections of the object’s activity,

p(x

r

, φ, z) = c

f (x, y, z) dy

r

, (5.42)

where the constant c is usually ignored.

The image reconstruction algorithms assume that the data are in a parallel-

projection format given by sinograms, the creation of which is, therefore,

mandatory for the reconstruction step. Image reconstruction approaches can

be either analytical or iterative [41], depending on whether they construct

an estimate of the activity distribution by analytically inverting Equation

5.41 or by trying to find the activity distribution that best matches the mea-

sured projections according to pre-established criteria, using methods based

on successive approximations. Some of the main reconstruction algorithms

are discussed in Chapter 6.

5.3.2 PET

5.3.2.1 Physical Principles and Limits

In a PET scanner, the photons produced in annihilation events occurring

within the patient leave its body and are individually detected by a set of

discrete detectors, usually arranged in a circular ring around the patient. If

two of those photons are detected within a very short space of time, the sys-

tem’s time window typically being a few nanoseconds, it is assumed that the

pair has been detected in coincidence, that is, that both photons originated

fromthe same annihilation event. Knowing the location of the triggered detec-

tors and taking into account that each annihilation gives rise to two photons

emitted in opposite directions, it is possible to trace the direction of emission

of the two detected photons with the line joining the detectors and to define

the LOR of the coincidence event (Figure 5.29).

If the photon detectors are particularly fast and the signal they produce

is short enough, of the order of hundreds of picoseconds, a portion of the

LOR where the annihilation took place can be identified by measuring the

time difference between the instants when the two photons are detected. This

technique is known as TOF-PET. Only a few scanners currently in opera-

tion have TOF capabilities, although it is likely that TOF-PET scanners will

be dominant very soon. This will increase sensitivity, which is greater the

Radiation Detectors and Image Formation 179

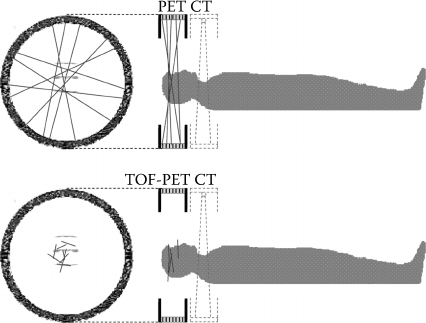

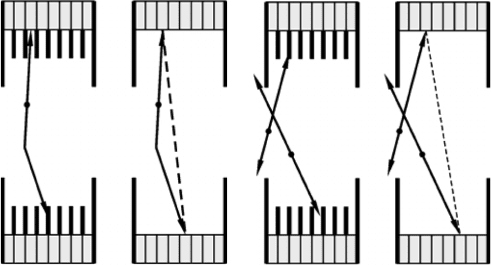

FIGURE 5.29

Typical acquisition geometry of a whole-body PET exam. Top: conventional PET, in which lines

of response join pairs of detectors. Below: TOF-PET, where the annihilation region is reduced

to a portion of the triggered LOR. The faster the detectors used, the smaller is the portion, and

the annihilation site becomes better defined. The location of the annihilation is assumed to be

describedby a Gaussian probabilitydistribution along that portion, contrary to conventional PET,

where it is assumed that the annihilation event has equal probability of having been generated

over the full extent of the LOR.

shorter the LOR portion within which the annihilation event can be located.

It should be noted that no increased spatial resolution of TOF-PET scanners is

foreseen, as detector development does not indicate that we shall be having

very fast detectors in the near future, which would be capable of pinpointing

the annihilation site within the LOR with the necessary accuracy.

The PET scanner, thus, counts the number of 511 keV photon pairs in coin-

cidence for each LOR defined in the system (Figure 5.30); since the direction

of the emitted pair of photons in a given annihilation event is random, it

is possible to create parallel projections of the activity distribution in the

patient by organizing the counts in sets of parallel LORs. We, thus, get position

information about the annihilation location without having to use physical

collimation, contrary to what happens with SPECT, where a collimator is

essential to the formation of parallel projections, as noted in Section 5.1. This

feature of PET is known as electronic collimation, and it gives PET an impor-

tant advantage over other NM techniques, because it dispenses the need for

a physical collimator. Hence, PET has the potential to accept pairs of photons

emitted in any direction, using all the decay events occurring in the patient

and not just those that lead to photons being emitted along the narrow solid

angle accepted by a physical collimator. The PET is, therefore, considerably

more sensitive compared with all the other NM techniques; it requires the

administration of a smaller amount of radiotracer to the patient for the same

image quality, which reduces the risk of harming the patient’s health and the

cost of the exam.

180 Nuclear Medicine Physics

E

1

,E

2

≈ 511 keV?

t

1

≈ t

2

?

Yes

Coincidence

true,

scattered and

random

E

1

E

2

LOR

t

1

t

2

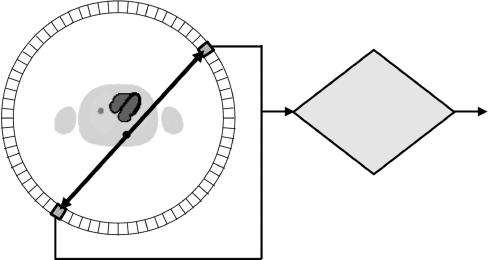

FIGURE 5.30

If two photons are detected in coincidence, it is assumed that they originated in the same anni-

hilation event. The line that joins the two detectors triggered in the coincidence is known as

line-of-response (LOR) and corresponds to the direction of the pair of photons emitted in the

annihilation event.

Although the spatial resolution of PET scanners is usually better than that

achieved in SPECT, there are certain physical limits imposed on the resolution

in PET that do not exist in SPECT. These limits arise from two independent

aspects: the range of the positron before the annihilation and the fact that the

emission directions of the two annihilation photons are not perfectly collinear.

The combination of these two effects leads to spatial resolutions that, in prac-

tice, are no better than about a tenth of a millimeter to several millimeters,

depending on the radioisotope employed, the radius of the detector ring, and

whether there are intense magnetic fields.

The average energy with which the positron is emitted in the beta decay

depends on the particular radioisotope being used and determines the aver-

age length of the path it will travel before being annihilated. The location of

the annihilation event, thus, slightly differs from the decay site, leading to an

intrinsic uncertainty about the position of the radiotracer; and this imposes a

fundamental limit on the spatial resolution attained in a given PET scanner,

with the chosen radioisotope.

The other physical limit on the spatial resolution arises from the fact that

the positron–electron pair may have nonzero momentum at the time of anni-

hilation. In this case, the angle between the directions of the two annihilation

photons is slightly deviated from 180

◦

(about ±0.25

◦

) [2], which results in

a small error while locating the position of the radiomarker. This degrades

the spatial resolution, with degradation worsening the further the radiation

detectors are from the patient.

The spatial resolution of an imaging system is a very important parameter,

as it corresponds to the minimum distance between two points in the object

that allows them to be observed as two distinct points in the image. This

feature is parameterized by the FWHM of the system’s PSF, obtained by the

Radiation Detectors and Image Formation 181

imaging of a point-like activity source. The full width at tenth maximum

(FWTM) is often also used, if the PSF has a non-Gaussian shape.

The near future foresees these two physical effects as the main factors

limiting the spatial resolutionin a PET scanner,although at present spatial res-

olution is still dominated by aspects related to technical implementation that

limit the resolution in commercially available systems to about 1 mm [46] for

animal PET, about 2 mm in state-of-the-art whole-body PET scanners [47], and

above 4 mm in most ordinary scanners. Today, the main factors governing the

spatial resolution of a PET system are the size of the detectors, the preponder-

ant factor until recently, and the image reconstruction process, which implies

the use of filters to increase the SNR but that blur the image and decrease the

ability of the system to distinguish between fast spatial changes of the activ-

ity. This parameter can be estimated in systems with detector blocks by an

empirical equation proposed in [48], obtained from a comprehensive analysis

of a large number of scanner models. The equation reads

Γ = 1.25

d

2

2

+(0.0022D)

2

+r

2

+b

2

, (5.43)

where Γ is the spatial resolution of the reconstructed image, d is the width of

a single crystal detector, D is the diameter of the detection ring (included to

take into account noncollinear emission), r is the effective dimension of the

point-like source (including the positron’s path), and b is the uncertainty in

the position of a photon detection event inside one detector block (which is

larger when the scintillation light is shared among crystals and smaller when

the light readout is performed by individual detectors). The constant factor

of 1.25 affecting the whole value is due to the image reconstruction process.

This equation supposes that there is no under-sampling, a factor which may

also degrade resolution.

Spatial resolution also depends on the position of the activity source

(although considerably less than in SPECT); it is generally worse on the

periphery of the field-of-view (FOV) of the scanner, due to the curvature of

the camera and the depth-of-interaction (DOI) effect. This has been the sub-

ject of recent technical developments aimed at its correction. Patient motion

is yet another element that degrades image resolution; some current systems

have optical setups that measurethe external motion and use that information

to correct the image. Internal motion such as breathing or heart movement

is harder to correct, but several methods are being currently developed to

address that problem.

Finally, there is the possibility of bypassing the resolution limit imposed by

the positron’s path before annihilation using high-intensity magnetic fields

in the range of 5–10 T [49–51]. Nevertheless, the limit due to noncollinear

photon emission still holds; so this application will be mostly important in

PET scanners with small detector ring radii, that is, those used in animal

182 Nuclear Medicine Physics

imaging, where record-breaking values for spatial resolution will certainly

be attained.

5.3.2.2 Data Acquisition

5.3.2.2.1 Types of Events

Although coincidence detection in a PET scanner always assumes that each

detected coincidence adds useful information to the radiotracer’s activity

map, in reality not all of them have valid positional information regarding

annihilation events. When an individual photon is detected, it is referred to

as the detection of a “single.” In spite of not being used in image formation,

singles are easily the most basic events handled by the PET scanner, and

they may be over two orders of magnitude more numerous than the num-

ber of coincidences. If the system detects three or more singles in the same

time window, the event is called a multiple coincidence and is rejected, as it

becomes impossible to ascribe an LOR to that event. It is only when the sys-

tem detects two singles in the same time window that a coincidence is said to

have happened; coincidences are classed as true (or nonscattered), scattered,

and random (Figure 5.31).

2 photons detected simultaneously

3 or more photons

detected

simultaneously

Only 1 photon

detected

Useful event for

image formation

Undetected

Undetected

LOR

LOR

LOR

Multiple

Random (R)

Delayed

(estimate of R)

Prompt

(T+S+R)

Scatter (S)

True (T)Single

FIGURE 5.31

Types of events detected in PET. For true coincidences, the detection event is counted in the

correct position (LOR); true coincidences are the only type of event of interest to noiseless image

formation. For scattered coincidences and random coincidences, at least one of the two photons

detected is not emitted along the LOR defined by the two detectors triggered (dashed line), and so

incorrect spatial information is conveyed to the data, which is expressed as image noise. Besides

being named according to the type of event, coincidences can be further classed as “prompts”

and “delayed,” respectively, for the total of two-photon coincidences detected by the system

(=T+S+R) and for the estimate of random coincidences using the delay line method.

Radiation Detectors and Image Formation 183

True coincidences are the only ones having valid position information,

because they correspond to the detection of two photons that were actually

emitted along the LOR of that coincidence. Scattered and random coinci-

dences, on the other hand, impart counts to LORs with photons that were not

originally emitted along the LOR in which they are added, and they solely

contribute to the addition of noise in the final image.

In a scattered coincidence, at least one of the two emitted photons in the

annihilation undergoes Compton scattering, an event that lowers the energy

of the scattered photon and changes its direction. Using the triggered LOR

leads to a wrong location for the annihilation site. In certain acquisition planes

of a typical whole-body exam, the number of scatteredcoincidences can easily

surpass the number of true coincidences.

For a random coincidence, the two photons detected arise from two dis-

tinct, but almost simultaneous, annihilations; and the corresponding photon

pairs are not detected by the system. The number of these events can also be

larger than the number of true coincidences, especially if the activity in the

FOV is high and the detectors are slow, which forces the use of a wider time

window. The probability of detecting a random coincidence in a given LOR

increases with the singles count rates R

s1

and R

s2

in the two individual detec-

tors defining that LOR and also with the length of the system’s time window.

It is easy to show that the random coincidences rate in that LOR is given by

R = 2ΔtR

s1

R

s2

, (5.44)

as long as the singles count rates are much larger than the coincidences count

rate, and any dead time effects may be ignored. If one assumes that R

s1

∼

=

R

s2

∼

=

R

s

(individual detectors as similar as possible with approximately the

same flux of coincidence photons in each detector), Equation 5.44 becomes

R = 2ΔtR

2

s

. (5.45)

5.3.2.2.2 Acquisition Geometry

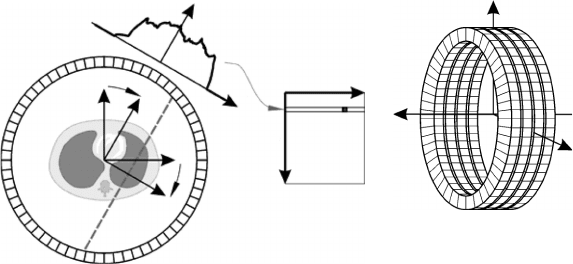

Most PET scanners are composed of thousands of small scintillation crystals

arranged around the region where the patient lies, the FOV. The layout of the

crystals, each of which is an individual photon detector, is usually cylinder

shaped, which allows coverage of a large solid angle of detection, because the

pairs of annihilation photons are emitted in just about all spatial directions.

In whole-body PET systems (Figure 5.29), the gantry can move the patient

inside the FOV along the axial direction and perform sequential acquisitions

to build up the full image of the patient’s body.

The individual crystals are normally grouped in detector blocks, that is, of

8 ×8 crystals coupled to four photomultipliers. The crystals belonging to a

detector block are usually produced from one large single crystal, which is

segmentedby longitudinal cuts of different depthsthat aresubsequentlyfilled

184 Nuclear Medicine Physics

with a reflective material. Detector blocks can also be grouped in larger struc-

tures called modules (typically with 4 blocks/module, although this number

varies considerably), and the whole set constitutes the full detector. This orga-

nization is very efficient from the point of view of the electronics needed

to detect photons and determine coincidences, but it is not useful when it

comes to organizing the data in sinograms and image reconstruction; for that

purpose, it is better to consider that the individual scintillation crystals are

grouped in rings lined up along the scanner’s axis.

In the early twenty-first century, commercial PET systems began to include

a CT subsystem with the intention of combining anatomic and functional

information. This had a considerable impact in the world of clinical diagno-

sis and led to the fast spreading of PET or CT scanners. Nowadays, almost

all commercially available systems are PET or CT scanners; not only do these

combine the anatomic information offeredby CT with the functional informa-

tion conveyed by PET, but they also offer better quality attenuation correction

(less noise and better spatial resolution) by constructing attenuation maps

from CT information, duly converted to PET photon energies. However, this

change in the attenuation correction has also raised new problems, namely,

artifacts due to misalignments between the PET and CT images. Multimodal

systems such as PET or CT are further described in Section 5.3.3.

5.3.2.2.3 Acquisition Modes

The principle of image formation in PET is based on counting the number of

truecoincidences detected in each LOR. This LOR by LOR reckoning,together

with the extremely large number of crystals in current PET systems, generates

several tens of millions of distinct LORs and leads to volumes of data gathered

in a PET exam, which can easily reach several hundreds of MB of information.

In PET, data can be collected using different acquisition philosophies, corre-

sponding to the 2D and 3D modes described below, and organized (or not)

in structures that may or may not be directly used in image reconstruction

methods.

Until the end of the 1980s, PET systems were solely operated in an acqui-

sition mode known as 2D mode, in which the scanner’s rings are separated

by physical septa of a lead–tungsten alloy, projected by about 10 cm into

the camera [52]. This mode is similar to data acquisition in SPECT, as the

septa play the same role in providing physical collimation, similar to what

the collimators of gamma cameras do. In PET, the septa, besides limiting

data acquisition and the corresponding image reconstruction to sets of 2D

planes stacked along the scanner axis, also protect each ring from photons

scattered off-ring and eliminate the need to correct the data from scattered

coincidences. In 1988, pioneering work developed at London’s Hammersmith

Hospital showed that the sensitivity could be substantially increased if the

septa were removed (see [53,54], and references therein). Since then, all com-

mercial PET systems started offering the possibility of executing exams with

no septa, in a new acquisition mode, termed 3D mode.

Radiation Detectors and Image Formation 185

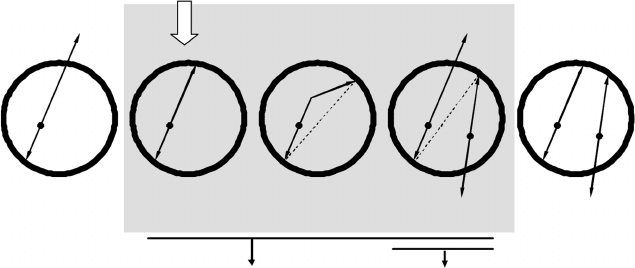

The greatest sensitivity to true coincidences of the 3D mode, typically 5

times better than that attained in the 2D mode [53,54] (Figure 5.32a), is due to

thefact that acquisition is performedover alargersolid angle, andinformation

from more LORs is used (Figure 5.32b). In fact, the 2D mode does not use the

full potential of electronic collimation, because the septa introduce physical

collimation and limit the acquisition to LORs between crystals residing in the

same or adjacent rings, leaving out steeper LORs.

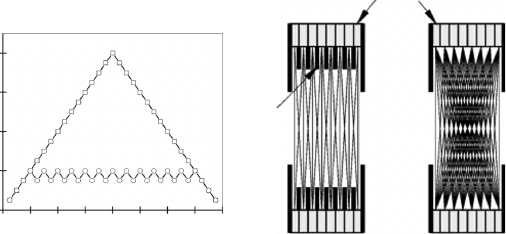

By being more sensitive to true coincidences, the 3D mode has the advan-

tage of allowing the amount of radiotracer given to the patient to be reduced

(or, using the same amount, the acquisition time can be reduced, or a better

image quality is provided). Nevertheless, detecting coincidences over a wider

solid angle by removing the septa also improves the sensitivity to scattered

and random coincidences [53] (Figure 5.33). The enhanced sensitivity to scat-

tered coincidences means that the data from this type of background have to

be corrected, which often involves sophisticated models of correction. Addi-

tionally, a greater number of random coincidences drives the system nearer

to saturation, requiring the use of detectors and electronics with a very short

dead time.

5.3.2.3 Data Storage

5.3.2.3.1 Data Formats

As happens in SPECT, events detected in a PET system may be stored using

either the list-mode format or a histogram format. In the first format, the data

are recorded as a sequential list of coincidence events, where in each entry a

16

12

8

Relative sensitivity

4

0

048121620

2D mode

3D mode

Transaxial plane

24 28 32

2D mode 3D mode

Crystals

(a) (b)

Septa

FIGURE 5.32

(a) Estimate of the sensitivity to true coincidences in the 2D and 3D modes calculated from

the number of LORs that intersect each of the transaxial planes possible to define in a 16-ring

scanner. The sensitivity in the 3D mode changes linearly along the camera axis, being maximal

in the centre of the axial FOV; for the 2D mode, this quantity is approximately constant over the

axial FOV. (b) Axial view of the LORs used in a PET scanner in 2D and 3D modes. The absence

of septa in the 3D mode makes it possible to use considerably more LORs, with a subsequent

increase in sensitivity.

186 Nuclear Medicine Physics

2D mode 3D mode 2D mode 3D mode

(a) (b)

FIGURE 5.33

(a) Effect of removing the septa on the sensitivity to (a) scattered and (b) random coincidences.

The angular acceptance of the crystals is larger in the 3D mode, which increases the sensitivity

to true coincidences and scattered and random coincidences.

set of items of information about the coincidence is written. This information

includes the indexes of the two crystals triggered (in the numbering scheme

defined for the detector), the energies of the two detected photons, or the

instant when the coincidence was detected. In the second format, the data are

collected in a multidimensional array which maps all the LORs that can be

defined in the system, one per entry of the array; the integer number stored

in each element of the array coincides with the total number of coincidences

detected in the corresponding LOR.

Data acquisition in PET systems, just as in modern SPECT scanners, is

normally performed in list-mode format and then converted to a histogram

format. The conversion tools use knowledge about the physical arrangement

of the detector, that is, the positions of the crystals. The list-mode format

also has greater potential for data correction in PET and depends neither on

the particular choice of “possible” LORs done for a particular system nor on

the spatial discretization imposed by those LORs. In addition, it is, in many

situations, the most compact type of format for the storage of 3D mode data.

5.3.2.3.2 2D Sinograms

As happens in SPECT, the basic histogram structure used for data acquired

in the 2D mode is typically the sinogram, which is now a 2D array of the

coincidences recorded in LORs belonging to a specific plane. The plane is

simultaneously perpendicular to the scanner axis and parallel to the detector

rings. The two indexes of a sinogram’s entry define the spatial orientation in

thatplane of the LORcorresponding to the entry, accordingto the LOR’s radial

and azimuthal coordinates x

r

and φ (Figure 5.34a). In addition the definition of

these coordinates underlies the existence of a OX

r

Y

r

reference frame rotated

Radiation Detectors and Image Formation 187

ϕ

ϕ

ϕ

x

r

y

r

y

x

r

x

r

x

Sinogram

z

Number of photon

counts

x

y

(a) (b)

FIGURE 5.34

(a) Definition of the coordinates x

r

and φ of an LOR (dashed line) relative to the OX

r

Y

r

reference

frame (obtained by rotating the OXY frame fixed to the scanner by an angle φ), and corresponding

location on the 2D sinogram. (b) Orientation of the XYZ reference frame fixed to the scanner. The

XY, YZ, and XZ planes are again the transaxial, sagittal, and coronal planes, respectively.

relatively to the scanner by a clockwise angle φ ∈[0; π]. The axial coordinate

z of each sinogram is defined by the position of the plane along the OZ axis

coinciding with the scanner axis (Figure 5.34b). In PET, the 2D sinograms of

an object relative to all 2D acquisition planes are also grouped in a 3D array

s

2D

(x

r

, φ, z). It should be noted that in PET the azimuthal coordinate varies in

the range 0

◦

to 180

◦

due to the symmetry in the emission of two annihilation

photons along opposing directions; whereas in SPECT the rotation angles

are in the range 0

◦

to 360

◦

, because there is only one photon emitted per

radiomarker decay.

Each row in a 2D sinogram groups parallel LORs that form an angle, φ, with

the horizontal direction, and each column collects LORs with the same radial

coordinate x

r

. The layout of rows and columns in a 2D sinogram is identical

to that shown in Figure 5.28 for SPECT, with the difference that the azimuthal

coordinate runs in the interval [0; π]. The range of radial positions for each

row of the sinogram covers the FOV’s diameter (twice the FOV’s radius, i.e.,

2 ×R

FOV

), which is normally less than the size of the crystal rings, as the

LORs farther from the FOV’s centre, which have a low information content

and need specific processing, are usually ignored. The 2D sinogram in PET is

also well suited to the usual image reconstruction algorithms, as each element

represents the number of coincidences detected in the corresponding LOR,

and the proportionality between that number and the integrated activity of

the radiomarker over the LOR’s direction still holds. Each rowof the sinogram

is again the projection of the object’s activity along the direction φ in the plane

z, p(x

r

, φ, z), that is,

p(x

r

, φ, z) = s

2D

(x

r

, φ, z), (5.46)