Kutz M. Handbook of materials selection

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

198 COPPER AND COPPER ALLOYS

perature (e.g., pure copper) or over a narrow temperature range (yellow brasses)

tend to be more forgiving of solidification rate and can generally be cast by a

variety of methods. Alloys with broad freezing ranges require slower solidifi-

cation rates (as in sand casting) in order to avoid excessive internal porosity.

These are not hard and fast rules, however, and they can often be abridged by

careful design and foundry practice.

A better understanding of the importance of freezing behavior has led to a

growing interest in the permanent-mold casting process in the United States. The

process makes use of ‘‘permanent’’ metal dies that induce rapid solidification

and therefore enable short cycle times and high production rates. Among the

process’s other advantages are the ability to produce near net shapes, fine surface

finishes, close tolerances, and exceptional part-to-part uniformity. Thin section

sizes are also readily attainable. The permanent-mold process is considered

friendly to the environment because it leaves virtually no residues for disposal.

From the designer’s standpoint, the method’s most significant advantage is that

the dense structure and fine grain size it produces results in castings having

higher strength, for the same alloys, than those available in sand castings. For

alloy C87500, a silicon brass, tensile strengths (TS) for sand-cast and permanent-

mold cast versions are 462 MPa (67 ksi) and 562 MPs (80 ksi), respectively, a

21% difference. Table 7 contains several other examples that illustrate this phe-

nomenon.

9.2 Uses

The plumbing industry is the largest user of copper castings, mainly for brass

fixtures, fittings, and water meters. Among the commonly used alloys are

C83600, a leaded red brass, C84400, a semired brass, and several of the yellow

brasses, the latter often being specified for decorative faucets and similar hard-

ware.

Traditional plumbing brasses contain lead to improve castability and machin-

ability. Concerns expressed in recent years over the possibility that a portion of

the lead might be leached from a plumbing fixture’s internal surfaces by ag-

gressive water and thus enter the human food chain led to the development of

several new alloys, aptly named EnviroBrasses. These brasses contain only trace

amounts of lead up to a maximum of 0.25%. EnviroBrass I (C89510) and

EnviroBrass II (C89520) substitute a mixture of selenium and bismuth for the

lead contained in conventional red and semired brasses. EnviroBrass III

(C89550) is a yellow brass that is ideally suited to the permanent-mold casting

process.

Industrial pumps, valves, and fittings are other important outlets for copper

alloy castings. Alloys are generally selected for favorable combinations of cor-

rosion, wear, and mechanical properties. Popular alloys include aluminum

bronze, nickel –aluminum bronze, tin bronzes, manganese bronze, and silicon

bronzes and brasses.

Copper alloys have been used in marine products for centuries, and that trend

continues today. The copper metals exhibit excellent general corrosion resistance

in both fresh and seawater. Unlike some stainless steels, they resist pitting and

stress-induced cracking in aggressive chloride environments.

10 COPPER IN HUMAN HEALTH AND THE ENVIRONMENT 199

Commonly selected alloys include dezincification-inhibited brasses, tin

bronzes, and manganese, silicon, and aluminum bronzes. For maximum seawater

corrosion resistance, copper–nickels should be considered.

Decorative architectural hardware is often cast in yellow brass. Plaques and

statuary make use of the copper metals’ ability to reproduce fine details, and the

alloys’ wide range of colors—including natural and synthetic patinas—have long

been favored by artists and designers.

9.3 Sleeve Bearings

Sleeve bearings deserve mention here because, with the exception of oil-

impregnated powder metal bearings, most bronze bearings are produced as either

continuous or centrifugal castings. Design of sleeve bearings is based on design

loads, operating speeds, temperature, and lubricant and lubrication mode. Selec-

tion of the optimum alloy for a particular design takes all these factors into

account; however, journal hardness and alignment, possible lubricant starvation,

and other unusual operating conditions must also be considered.

Tin bronzes, leaded tin bronzes, and high-leaded tin bronzes are the most

commonly specified sleeve bearing alloys, alloy C93200 being considered the

workhorse of the industry. Tin imparts strength; lead improves antifrictional

properties but does so at the expense of some strength. High-leaded tin bronzes

have the highest lubricity but the lowest strength of the bearing alloys. Alumi-

num bronzes and manganese bronzes are selected for applications that require

very high strength and excellent corrosion resistance.

A useful primer on sleeve bearing design can be found at http://

www.copper.org/industrial/bronze bearing.htm. PC-compatible sleeve bearing

design software is available from CDA.

10 COPPER IN HUMAN HEALTH AND THE ENVIRONMENT

There has been a trend recently for engineers to take a material’s health and

environmental effects into account during product design, and ‘‘heavy metals’’

such as lead and cadmium, alone or in alloyed form, have lost favor despite

whatever benefit they brought to market. While copper is chemically defined as

a heavy metal, its use should give designers no concerns in this regard. Copper

has, in fact, rightly been called an environmentally ‘‘green’’ metal.

Copper is essential to human, animal, and plant life. It is especially important

to expectant mothers and infants. Without sufficient dietary intake to maintain

internal stores, people suffer metabolic disorders and a variety of other problems.

Animals fail to grow properly when copper is not provided in their feed or if

they graze on copper-deficient plants. Crops grown on copper-deficient soils

produce lower yields and some plants may simply wither and die.

On the other hand, copper does exhibit toxicity under some circumstances.

This property is exploited beneficially in, for example, antifouling marine paints,

agricultural fungicides, and alloys for seawater piping systems. In the United

States, federal regulations limit public water supplies to copper concentrations

to 1.3 parts per million (ppm)—the limit in Europe is 2.0 ppm—but higher

levels found in some well waters are objectionable mainly because of the

metallic taste the metal imparts. The threshold for acute physiological effects,

200 COPPER AND COPPER ALLOYS

mainly nausea and other temporary gastrointestinal disorders, is estimated to lie

between 4 and 6 ppm, although sensitivity varies widely among individuals.

There has been concern expressed over the discharge of copper in effluents

from copper roofs and copper plumbing systems. Copper may exist in such

effluents in minute quantities, mainly bound as chemical compounds and com-

plexes that are not ecologically available. Such forms of copper differ from ionic

copper, which can exhibit ecotoxicity but which appears to exist only briefly in

nature owing to copper’s very strong bonding tendency, leading it to form non-

bioavailable or nontoxic chemical compounds.

Finally, the fact that almost all copper is eventually recycled into useful prod-

ucts deserves recognition as one of the metal’s environmental benefits. Currently,

about 45% of all copper in use has been used in some form before. Largely

because of the metal’s high value, almost none of it finds its way to landfills.

Recycling not only conserves a natural resource, it also avoids re-expenditure

of the energy needed for mining, smelting and, refining.

201

CHAPTER 6

SELECTION OF TITANIUM ALLOYS

FOR DESIGN

Matthew J. Donachie

Rensselaer at Hartford

Hartford, Connecticut

1 INTRODUCTION 201

1.1 Purpose 201

1.2 What Are Titanium Alloys? 202

1.3 Temperature Capability of

Titanium Alloys 202

1.4 Strength and Corrosion

Capability of Titanium and Its

Alloys 203

1.5 Titanium Alloy Information 203

2 METALLURGY OF TITANIUM

ALLOYS 204

2.1 Structures 204

2.2 Crystal Structure Behavior

in Alloys 205

3 METALS AT HIGH

TEMPERATURES 205

3.1 General 205

3.2 Mechanical Behavior 206

4 MICROSTRUCTURE AND

PROPERTIES OF TITANIUM

AND ITS ALLOYS 208

4.1 Alloy Composition and

General Behavior 208

4.2 Strengthening of Titanium

Alloys 211

5 EFFECTS OF ALLOY ELEMENTS 211

5.1 Intermetallic Compounds and

Other Secondary Phases 211

5.2 Mechanical and Physical

Properties 212

5.3 Effects of Processing 214

5.4 Hydrogen (in CP Titanium) 214

5.5 Oxygen and Nitrogen (in CP

Titanium) 215

5.6 Mechanical Properties of

Titanium Alloys 215

6 MANUFACTURING PROCESSES 225

6.1 General Aspects of the

Manufacture of Titanium

Articles 225

6.2 Production of Titanium via

Vacuum Arc Melting 226

6.3 Forging Titanium Alloys 227

6.4 Investment Casting 229

6.5 Machining and Residual

Stresses 229

6.6 Joining 230

7 OTHER ASPECTS OF TITANIUM

ALLOY SELECTION 231

7.1 Corrosion 231

7.2 Biomedical Applications 231

7.3 Cryogenic Applications 232

8 FINAL COMMENTS 232

BIBLIOGRAPHY 233

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Purpose

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a reasonable understanding of titanium

and its alloys so that selection of them for specific designs will be appropriate.

HandbookofMaterialsSelection.EditedbyMyerKutz

Copyright Ó 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Inc., NewYork.

202 SELECTION OF TITANIUM ALLOYS FOR DESIGN

Knowledge of titanium alloy types and their processing should provide a poten-

tial user with a better ability to understand the ways in which titanium alloys

(and titanium) can contribute to a design. Furthermore, the knowledge provided

here should enable a user of titanium alloys to:

●

Ask the important production questions of titanium providers.

●

Specify necessary mechanical property levels to optimize alloy perform-

ance in the desired application.

●

Determine the relevant corrosion/environmental factors that may affect a

component.

Properties of the titanium alloy families sometimes are listed in handbooks or

vendor/supplier brochures. However, not all data will be available and there is

no special formula for titanium alloy selection.

Larger volume customers frequently dictate the resultant material conditions

that generally will be available from a supplier. Proprietary alloy chemistries

and/or proprietary/restricted processing required by customers can lead to alloys

that may not be widely available. In general, proprietary processing is more

likely to be encountered than proprietary chemistries nowadays. With few ex-

ceptions, critical applications for titanium and its alloys will require the customer

to work with one or more titanium producers to develop an understanding of

what is available and what a selector/designer can expect from a chosen titanium

alloy.

1.2 What Are Titanium Alloys?

Titanium alloys for purposes of this chapter are those alloys of about 50% or

higher titanium that offer exceptional strength-to-density benefits plus corrosion

properties comparable to the excellent corrosion resistance of pure titanium. The

range of operation is from cryogenic temperatures to around 538

⬚C (1000⬚F) or

slightly higher. Titanium alloys based on intermetallics such as gamma titanium

aluminide (TiAl intermetallic compound that has been designated

␥

) are included

in this discussion but offer no clear-cut mechanical advantages for now and an

economic debit in many instances.

1.3 Temperature Capability of Titanium Alloys

The melting point of titanium is in excess of 1660⬚C (3000⬚F), but commercial

alloys operate at substantially lower temperatures. It is not possible to create

titanium alloys that operate close to their melting temperatures. Attainable

strengths, crystallographic phase transformations, and environmental interaction

considerations cause restrictions. Thus, while titanium and its alloys have melt-

ing points higher than those of steels, their maximum upper useful temperatures

for structural applications generally range from as low as 427

⬚C (800⬚F) to the

region of about 538–595

⬚C (1000–1100⬚F) dependent on composition. Titanium

aluminide alloys show promise for applications at temperatures up to 760

⬚C

(1400

⬚F).

Actual application temperatures will vary with individual alloy composition.

Since application temperatures are much below the melting points, incipient

melting is not a factor in titanium alloy application.

1 INTRODUCTION 203

Table 1 Comparison of Typical Strength-to-Weight Ratios at

20ⴗC

Metal

Specific

Gravity

Tensile

Strength

(lb/ in.

2

)

Tensile

Strength ⫼

Specific Gravity

CP 4.5 58,000 13,000

Ti–6Al–4V 4.4 130,000 29,000

Ti–4Al–3Mo–1V 4.5 200,000 45,000

Ultrahigh-strength

steel (4340) 7.9 287,000 36,000

Source: From Titanium: A Technical Guide, 1st ed., ASM International,

Materials Park, OH 44073-0002, 1988, p. 158.

1.4 Strength and Corrosion Capability of Titanium and Its Alloys

Titanium owes its industrial use to two significant factors:

●

Titanium has exceptional room temperature resistance to a variety of cor-

rosive media.

●

Titanium has a relatively low density and can be strengthened to achieve

outstanding properties when compared with competitive materials on a

strength to density basis.

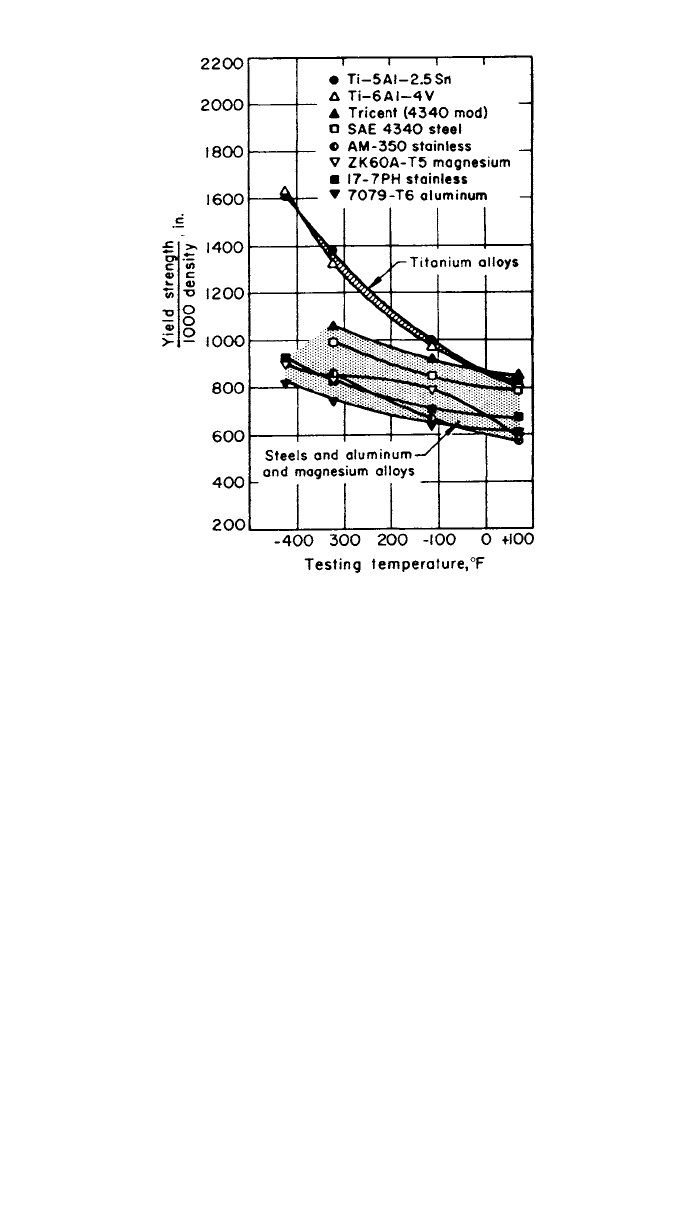

Table 1 compares typical strength-to-density values for commercial purity (CP)

titanium, several titanium alloys, and a high strength steel. Figure 1 depicts the

strength improvements possible in titanium alloys. In addition to the excellent

strength characteristics, titanium’s corrosion resistance makes it a desirable ma-

terial for body replacement parts and other tough corrosion-prone applications.

1.5 Titanium Alloy Information

While some chemistries and properties are listed in this chapter, there is no

substitute for consultation with titanium manufacturers about the forms (some

cast, mostly wrought) that can be provided and the exact chemistries available.

It should be understood that not all titanium alloys, particularly those with spe-

cific processing, are readily available as off-the-shelf items. Design data for

titanium alloys are not intended to be conveyed here, but typical properties are

indicated for some materials. Design properties should be obtained from internal

testing if possible, or from producers or other validated sources if sufficient test

data are not available in-house. Typical properties are merely a guide for com-

parison. Exact chemistry, section size, heat treatment, and other processing steps

must be known to generate adequate property values for design.

The properties of titanium alloy compositions that have been developed over

the years are not normally well documented in the literature. However, since

many consumers actually only use a few alloys within the customary user

groups, data may be more plentiful for certain compositions. In the case of tita-

nium, the most used and studied alloy, whether wrought or cast, is Ti–6Al–4V.

The extent to which data generated for specific applications are available to

the general public is unknown. However, even if such data were disseminated

widely, the alloy selector needs to be aware that processing operations such as

forging conditions, heat treatment, etc. dramatically affect properties of titanium

204 SELECTION OF TITANIUM ALLOYS FOR DESIGN

Fig. 1 Yield strength-to-density ratio as a function of temperature for several titanium alloys

compared to some steel, aluminum, and magnesium alloys. (From Titanium: A Technical Guide,

1st ed., ASM International, Materials Park, OH 44073-0002, 1988, p. 158.)

alloys. All data should be reconciled with the actual manufacturing specifications

and processing conditions expected. Alloy selectors should work with competent

metallurgical engineers to establish the validity of data intended for design as

well as to specify the processing conditions that will be used for component

production.

Application of design data must take into consideration the probability of

components containing locally inhomogeneous regions. For titanium alloys, such

segregation can be disastrous in gas turbine applications. The probability of

occurrence of these regions is dependent upon the melting procedures, being

essentially eliminated by so-called triple melt. All facets of chemistry and proc-

essing need to be considered when selecting a titanium alloy for an application.

For sources of property data other than that of the producers (melters, forgers,

etc.) or an alloy selector’s own institution, one may refer to handbooks or or-

ganizations, such as ASM International, that publish compilations of data that

may form a basis for the development of design allowables for titanium alloys.

Standards organizations such as the American Society for Testing and Materials

(ASTM) publish information about titanium alloys, but that information may not

ordinarily contain any design data.

2 METALLURGY OF TITANIUM ALLOYS

2.1 Structures

Metals are crystalline and the atoms take various crystallographic forms. Some

of these forms tend to be associated with better property characteristics than

3 METALS AT HIGH TEMPERATURES 205

other crystal structures. Titanium, as does iron, exists in more than one crystal-

lographic form. Titanium has two elemental crystal structures: in one, the atoms

are arranged in a body-centered cubic array, in the other they are arranged in a

close-packed hexagonal array. The cubic structure is found only at high tem-

peratures, unless the titanium is alloyed with other elements to maintain the

cubic structure at lower temperatures.

We are concerned not only with crystal structure but also overall ‘‘structure,’’

i.e., appearance, at levels above that of atomic crystal structure. Structure for

our purposes will be defined as the macrostructure and microstructure (i.e.,

macro- and microappearance) of a polished and etched cross section of metal

visible at magnifications up to and including 10,000

⫻. Two other microstructural

features that are not determined visually but are determined by other means such

as X-ray diffraction or chemistry are: phase type (e.g.,

␣

and

) and texture

(orientation) of grains.

Titanium’s two crystal structures are commonly known as

␣

and

. Alpha

actually means any hexagonal titanium, pure or alloyed, while beta means any

cubic titanium, pure or alloyed. The

␣

and

structures—sometimes called sys-

tems or types—are the basis for the generally accepted classes of titanium alloys.

These are

␣

, near-

␣

,

␣

–

, and

. Sometimes a category of near-

is also con-

sidered. The preceding categories denote the general type of microstructure after

processing.

Crystal structure and grain structure (a component of microstructure) are not

synonymous terms. Both (as well as the arrangement of phases in the micro-

structure) must be specified to completely identify the alloy and its expected

mechanical, physical, and corrosion behavior. The important fact to keep in mind

is that, while grain shape and size do affect behavior, the crystal structure

changes (from

␣

to

and back again) which occur during processing play a

major role in defining titanium properties.

2.2 Crystal Structure Behavior in Alloys

An

␣

-alloy (so described because its chemistry favors

␣

-phase) does not nor-

mally form

-phase on heating. A near-

␣

(sometimes called ‘‘superalpha’’) alloy

forms only limited

-phase on heating, and so it may appear microstructurally

similar to an

␣

-alloy when viewed at lower temperatures. An

␣

–

alloy is one

for which the composition permits complete transformation to

on heating but

transformation back to

␣

plus retained and/or transformed

at lower tempera-

tures. A near-

or

-alloy composition tends to retain, indefinitely at lower

temperatures, the

-phase formed at high temperatures. However, the

that is

retained on initial cooling to room temperature is metastable for many

-alloys.

Dependent on chemistry, it may precipitate secondary phases during heat treat-

ment.

3 METALS AT HIGH TEMPERATURES

3.1 General

While material strengths at low temperatures are usually not a function of time,

at high temperatures the time of load application becomes very significant for

mechanical properties. Concurrently, the availability of oxygen at high temper-

atures accelerates the conversion of some of the metal atoms to oxides. Oxidation

206 SELECTION OF TITANIUM ALLOYS FOR DESIGN

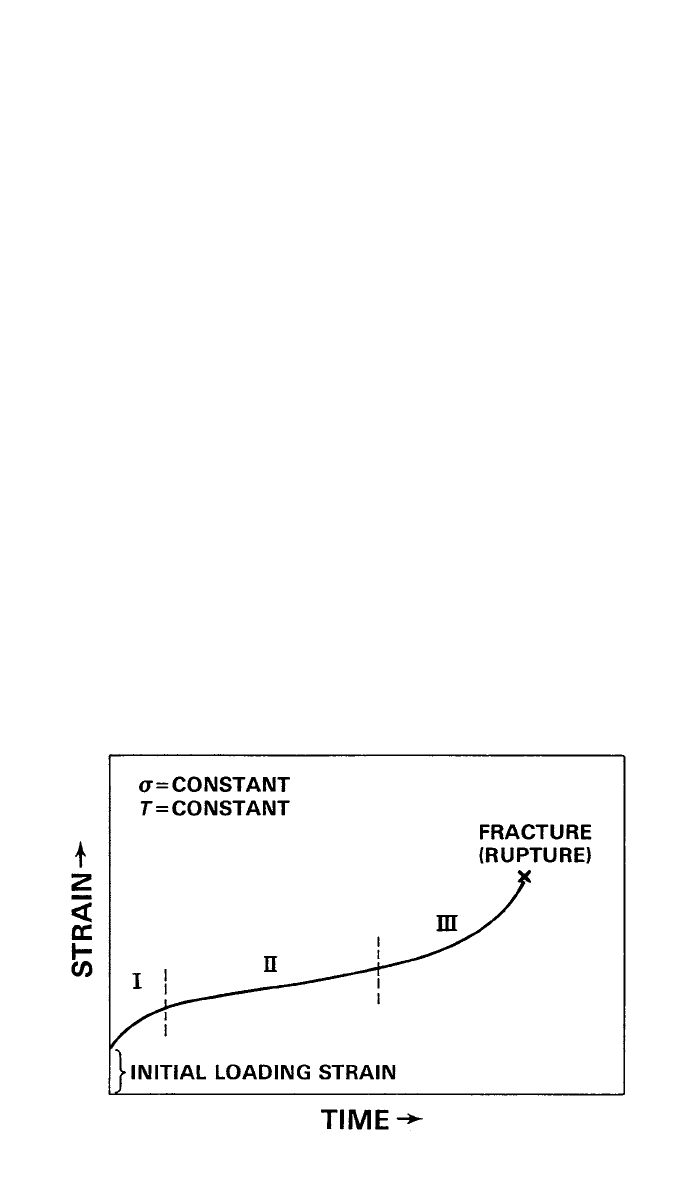

Fig. 2 Creep rupture schematic showing time-dependent deformation under constant load at

constant high temperatures followed by final rupture. (All loads below the short time yield

strength. Roman numerals denote ranges of the creep rupture curve.)

proceeds much more rapidly at high temperatures than at room or lower tem-

peratures. For alloys of titanium there is the additional complication of titanium’s

high affinity for oxygen and its ability to ‘‘getter’’ oxygen (or nitrogen) from

the air. Dissolved oxygen greatly changes the strength and ductility of titanium

alloys. Hydrogen is another gaseous element that can significantly affect prop-

erties of titanium alloys. Hydrogen tends to cause hydrogen embrittlement while

oxygen (and nitrogen) will increase strength and reduce the ductility but not

necessarily embrittle titanium as hydrogen does.

3.2 Mechanical Behavior

In the case of short-time tensile properties of yield strength (TYS) and ultimate

strength (UTS), the mechanical behavior of metals at higher temperatures is

similar to that at room temperature but with metals becoming weaker as the

temperature increases. However, when steady loads below the normal yield or

ultimate strength determined in short-time tests are applied for prolonged times

at higher temperatures, the situation is different. Figure 2 illustrates the way in

which most materials respond to steady extended-time loads at high tempera-

tures. A time-dependent extension (creep) is noticed under load. If the alloy is

exposed for a long time, the alloy eventually fractures (ruptures). The degrada-

tion process is called creep or, in the event of failure, creep-rupture (sometimes

stress-rupture), and alloys are selected on their ability to resist creep and creep-

rupture failure. Cyclically applied loads that cause failure (fatigue) at lower

temperatures also cause failures in shorter times (lesser cycles) at high temper-

atures. When titanium alloys operate for prolonged times at high temperature,

they can fail by creep-rupture. However, tensile strengths, fatigue strengths, and

crack propagation criteria are more likely to dominate titanium alloy perform-

ance requirements.

3 METALS AT HIGH TEMPERATURES 207

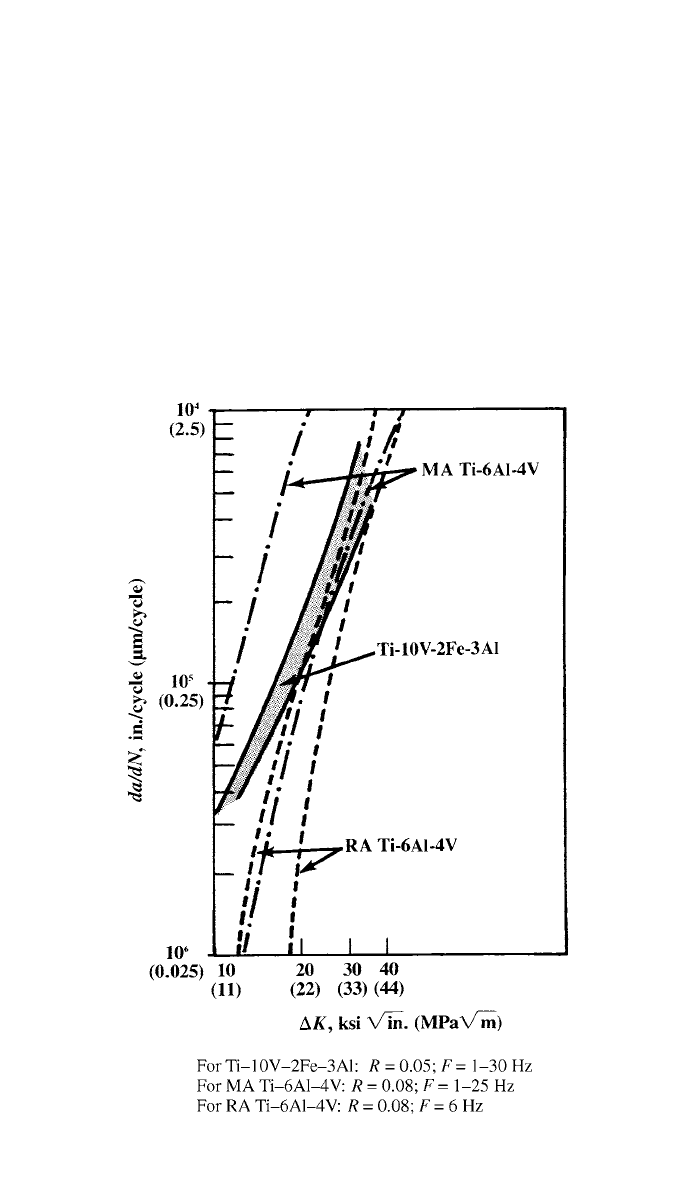

Fig. 3 Comparison of fatigue crack growth rate (da/ dn) vs. toughness change (⌬K). Curves for

several titanium alloys. Note that MA ⫽ mill annealed while RA ⫽ recrystallization annealed.

(From Titanium: A Technical Guide, 1st ed., ASM International, Materials Park,

OH 44073-0002, 1988, p. 184.)

In highly mechanically loaded parts, such as gas turbine compressor disks, a

common titanium alloy application, fatigue at high loads in short times, low

cycle fatigue (LCF) is the major concern. High cycle fatigue (HCF) normally is

not a problem with titanium alloys unless a design error occurs and subjects a

component to a high-frequency vibration that forces rapid accumulation of fa-

tigue cycles. While life under cyclic load (S–N behavior) is a common criterion

for design, resistance to crack propagation is an increasingly desired property.

Thus, the crack growth rate versus a fracture toughness parameter is required.

The parameter in this instance is the stress intensity factor (K) range over an

incremental distance which a crack has grown—the difference between the max-

imum and minimum K in the region of crack length measured. A plot of the

resultant type (da/dn vs.

⌬K) is shown in Fig. 3 for several wrought titanium

alloys.