Kristiansen Svein. Maritime Transportation: Safety Management and Risk Analysis

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

greater detail later in the chapter. True safety orientation is also visible through the

priorities set by top management. Fundamentally it is a matter of how safety is balanced

against time and money in daily operations.

1 5 .1.3 The Mar i ti m e Safety M anagemen t Regim e

The rules and regulations governing safety and environmental protection within the

shipping industry have evolved over time through what may be described as a set of

interrelated stages. The earliest and most basic stage focused primarily on the con-

sequences of accidents resulting from failures made in relation to safety. In the co ntext

of this safety regime, major efforts were made in the aftermath of accidents to find

someone to blame for personal injuries, fatalities, damage to or loss of ship and cargo, and

environmental pollution. This created a culture of punishment, where the essential theme

was to identify and allocate/apportion blame. Frequently the last people in the chain of

Ta b l e 1 5 . 2 . Safety orientation dimensions

Safety orientation dimensions Explanation

Safety view Safety incorporated as an essential part of the

business policy

Proactive attitude

Public responsibility

Long-term perspective

Set priorities Documented and visible policy

Give safety priority and allocate the necessary resources

Culture Credible leadership: ‘Do as you say’

True concern for safety at all levels of the organization

Establish a set of ‘symbols/heroes/rituals/values’

Human values Genuine concern for crew, staff and middle management

Emphasis on worker safety and health

Personnel policies that support motivation and

responsibility

Operate systematically Implement safety plan, programmes and routines

Establish a safety management system

TQM approach: Plan/do/check/review cycle

Protect against potential hazards Formal Safety Assessment (FSA), Safety Case approach

Risk-based engineering

Emergency preparedness

Proceed cautiously Limit the pace of technical innovations in each project

Design verification

Test the risks

Learn from experience Openness to risks and safety problems

Inspections, maintenance

Auditing of the safety management system

466 CH APTER 15 SA FETY MANAG EMENT

events, i.e. the peo ple at the sharp end of the system, were found responsible. The

underlying principle of this safety management regime was that the threat of punishment

should influence companies and individual behaviour to the extent that safety gained a

higher priority. Although the maritime safety management regime has principally evolved

away from this early stage of development, the culture of punishment is still to be found in

the aftermath of accidents as well as in many maritime regulations. For example, the US

Oil Pollution Act (OPA 90) gives shipowners full economic liability for oil spills in US

coastal waters.

What may be described as the second stage of development regarding the maritime

safety management regime involves the regulation of safety by prescription, i.e. the

prescriptive regime in which the maritime industry is given sets of rules and regulations to

be obeyed. For example, the provisions of ILLC 1966 (the International Convention on

Load Lines), SOLAS 1974 (the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea),

MARPOL 73/78 (the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from

Ships), COLREG 1972 (the Convention on the Internationa l Regulations for Preventing

Collisions at Sea) and STCW 78/95 (the Standards for Training, Certification and

Watchkeeping for Seafarers) provide the basis for the prescriptive (or external) regulatory

framework for international shipping. The prescribing party is normally a country

government or its legislative bodies, or an international organization in which a number of

countries participate (e.g. the IMO). The prescr ibed rules and regula tions have normally

been based on past experiences and very rarely have proactive rules been included. The

prescriptive regime affects and is employed in all parts of a vessel’s life-cycle, i.e. design,

construction, operation, modification/refurbishment, and decommissioning.

The second stage of development is an advance on the first stage (the culture of

punishment) because it is designed to attack known points of danger before actual harm

occurs. This leads to a culture of compliance with prescriptive rules. However, more

recently there has been a growing belief that the application of prescriptive rules is not

enough: rules and regulations provide the means to achieve safety, but this should not be

an end in itself.

The third and most advanced stage in the evolution of t he maritime safety

management regime is the creation of a so-called culture of self-regulation of safety,

where regulation goes beyond the setting of externally imposed compliance criteria as

in the second stage. The culture of self-regulation concentrates on internal management

and organization for safety, and encourages individual industries and companies to

establish targets for safety performance. Self-regulation also emphasizes the need for every

company and individual to be responsible for the actions taken to improve safety, rather

than seeing them imposed from external prescriptive parties. This requires the develop-

ment of company-specific and, in the case of shipping, vessel-specific safety management

systems (SMS ). It can be concluded that in the culture of self-regulation, safety is

organized by those who are directly affected by the implications of failure.

As mentioned earlier, the regulation of safety in the shipping industry has, historically,

been characterized by a culture of punishment and a culture of external compliance.

IMO’s adoption of the International Safety Management (ISM) Code, which is made

mandatory in all member states, is an important step towards the creation of a culture of

15.1 INTRODUC T ION 467

self-regulation in shipping. The increasing focus on safety management represents an

important transition from the traditional principle of prescriptive regulations that

dominate the maritime sector. Self-regulation is not, however, completely effective on its

own. In order to achieve safer seas and environmental pro tection it is necessary for all

three regimes/stages described above to coexist. Each regime plays a significant part in

influencing company and individual behaviour. The ISM code will be reviewed in detai l

later in this chapter.

With regard to improving maritime safety, the following factors and aspects have been,

and still are, in focus:

. Technical solutions

. Training and competence (i.e. human factors)

. Workplace conditions (i.e. ergonomics)

. Management and organization

. Risk-based planning and design

The causal factors resulting in ship accidents reveal that there is considerable potential

for improvement with regard to human and organizational factors (HOF), at least relative

to what can be gained today through the implementation of improved technical solutions

in North European and North American flag states. In the emerging Total Quality

Management (TQM) thinking there is an increasing tendency to see health, safety and

environment (HSE) as elements in an integrated management approach.

15. 2 TOTAL QUALIT Y MANAGEMENT ( TQM )

15.2.1 Basic Theory

As pointed out earlier, safety has traditionally been seen in a regulatory perspective. This

means that the shipowner or manager operates within the framework of prescriptive safety

regulations. This view is now changing rapidly because of the so-called quality thinking

that is gaining increasing acceptance and thereby blending the different aspects of quality

management together. Increasingly, safety management will therefore be seen as an

integral part of the overall management system of a company. Safety is only one of a

number of factors that express the quality of a business, which may involve the following

factors:

. Long-term perspective

. Customer orientation

. Leadership involvement

. Continuous improvement

. Fact-based management

. Employee involvement at all levels

. Good relations with subcontractors

. Corporate responsibility

. Good and effective health, safety, and environmental policies

468 CH APTER 15 SA FETY MANAG EMENT

Quality affects every aspect of business. A popular and emerging management

philosophy that bases itself on this all-embracing notion of quality is the so-called Total

Quality Management or TQM (Costin, 19 98). Juran (1998) has stated the following

motivations for the TQM approach:

. There is a crisis in quality.

. Our traditional ways of dealing with quality crises are inadequate.

. Quality management affects all functions and every level (of the hierarchy) of the

organization, and hence requires a universal way of thinking.

. There is a need for continuous learning and improvement at all organizationa l levels.

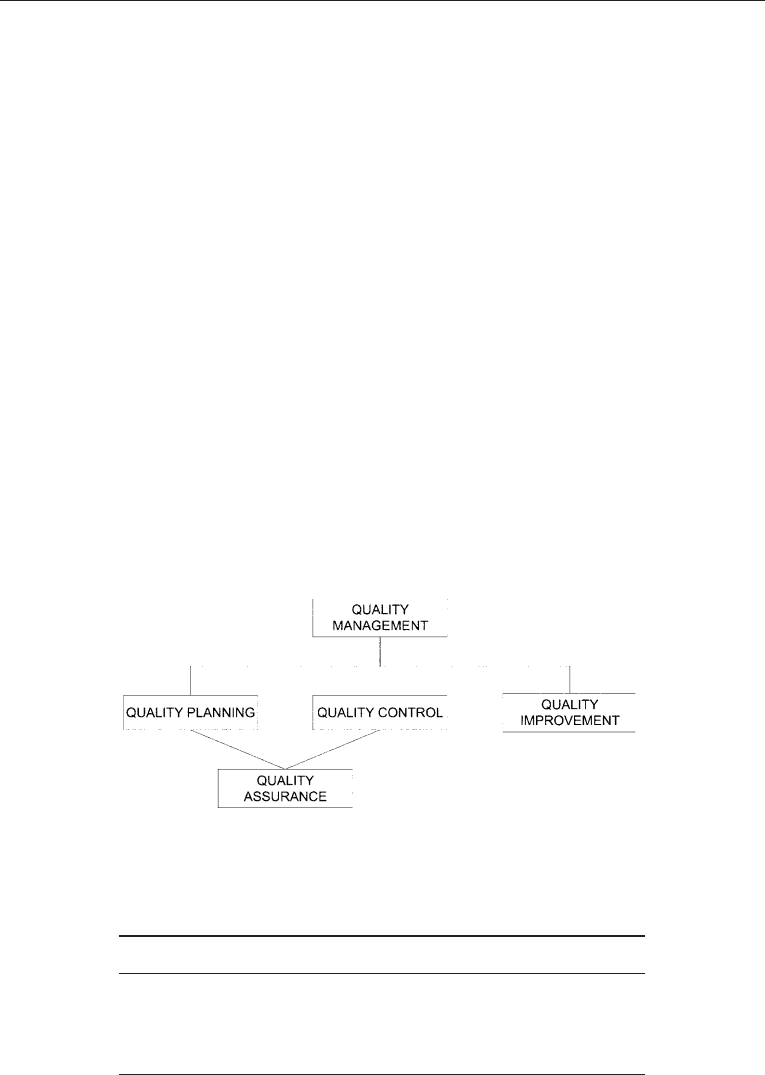

The so-called ‘Juran Trilogy’, as illustrated by Figure 15.1, focuses on quality planning,

control and improvement, as well as quality assurance. This quality model is the

underlying basis of the TQM philosophy. In order to clarify the concepts in Figure 15.1,

the quality of the financial function of an organization can be studied as shown in

Table 15.3.

Three important characteristics and key conditions of successful quality manage-

ment are a clear policy regarding quality, continuous improvement, and comprehensive

management commitment. In addition to presenting the quality model (i.e. Figure 15.1),

Juran (1998) also outlines the processes underlying each of the three basic quality

functions in this model, i.e. quality planning, quality control and quality improvement.

These processes are presented in Table 15.4.

Ta b l e 1 5 . 3 . The financial function of an organization seen in the context

of the quality model

Financial Quality

Budgeting Quality planning

Cost/expense control Quality control

Cost reduction, profit improvement Quality improvement

Audit Quality assurance

Figure 15.1. The quality model.

15.2 T O TAL QU ALITY MANA GEMENT (T QM) 469

15.2.2 Safety Management Based on TQM

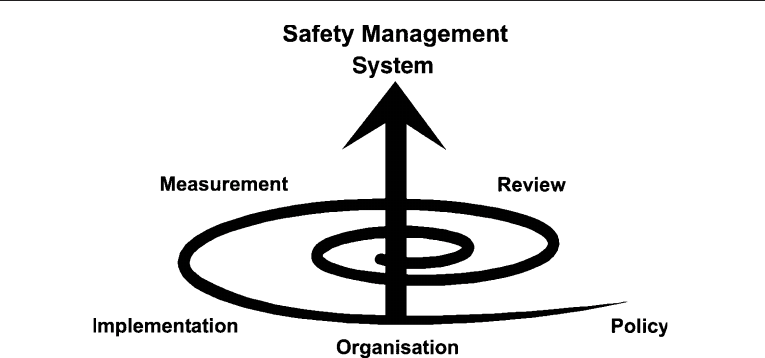

Central to the TQM philosophy is the so-called ‘plan/do/check/ review’ loop, in which

quality is improved on a continuous basis. As pointed out earlier, safety is a quality of

an organization. The organizational safety level can be managed through the use of a

set of basic safety management activities. These activities may be modelled in a ‘safety

management spiral’ as illustrated in Figure 15.2. The spira l form is used to indicate

that safety management within an organization should be an iterative process, which

is in accor dance with the important TQM prin ciple of continuous improvement

(Aitken et al., 1996).

The five basic components in the safety management system (SMS) in Figure 15.2,

which is heavily influenced by TQM , are as follows:

. Policy: All organizations have a set of policies that are used to guide the performance

of the staff so that the overall objective of the organization can be achieved in an

effective way. Safety goals (i.e. the level of safety one wishes to achieve) should be

included as a vital part of the policies. Policies have a tendency to be quite static

documents, but to achieve a well-functioning safety management system one must

Ta b l e 1 5 . 4 . The processes underlying quality planning, quality control and quality improvement

Quality planning Identify customers, both external and internal

Determine customer needs

Develop product features (both goods and services) that respond

to customer needs

Establish quality goals that meet the needs of customers and

suppliers alike, and do so at a minimum combined cost

Develop a process that can produce the needed product features

Prove process capability – prove that the process can meet

the quality goals under operating conditions

Quality control Choose control subjects, i.e. what to control

Choose units of measurement

Establish measurement

Establish standards of performance

Measure actual performance

Interpret the difference between actual and standard performance

Take action on the difference

Quality improvement Prove the need for improvement

Identify specific projects for improvement

Organize to guide the projects

Organize for diagnosis, i.e. for discovery of causes

Diagnose to find causes

Provide remedies

Prove that the remedies are effective under operating conditions

Provide for control to maintain gains

470 CHAPTER 15 SAFETY MANAGEM ENT

establish a culture where policies are developed and improved over time as a result of

the iterating safety management process.

. Organizat ion: It is of great importance that the management system establishes the

responsibilities of individuals with regard to safety matters. This has to be done with

an understanding of the needs of communication and co-operation between the

individuals involved, and the need for proper education and competence within the

organization.

. Implementation: The implementation phase should make sure that the policies and

objectives are translated into practice. The results of this implementation are ‘tested’

through the application of the SMS.

. Measurement: The objective of the measurement task is to measure whether the

implementation went as intended and its effectiveness. The information from this stage

is fed into the review phase/stage of the SM S.

. Review: It is necessary to have a mechanism for reviewing the performance of a

system and to seek ways to continuous ly improve it. The review phase/stage uses the

information obtained by measurement to review/audit and analyse the performance of

the system. Auditing is the only non-destructive way in which lessons can be learned

and fed into the system for enhancement. The review phase should examine the total

range of safety management activities, i.e. policies, orga nization, implementation and

measurement.

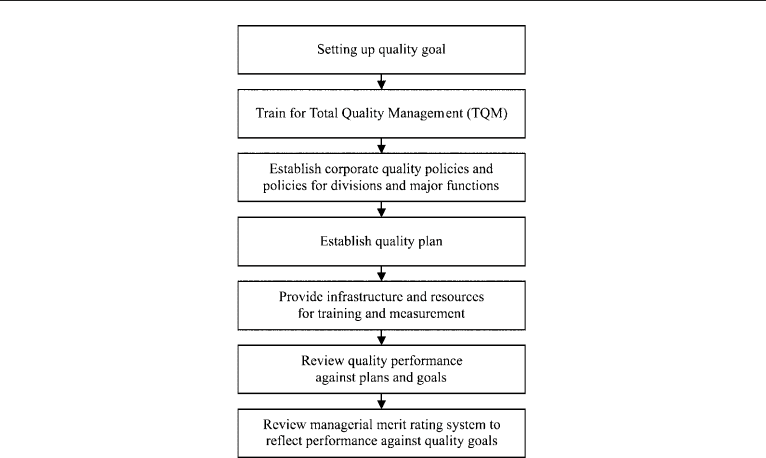

Clement et al. (1996) have outlined how principles from TQM can be applied in the

development of an integrated healt h, safety and environm ent (HSE) management system

suitable for implementation into all business processes. The process of introducing TQM

involves a number of steps, which can be illustrated by Figure 15.3. As can be seen from

Figure 15.2. Safety management modelled as a spiral illustrating safety management as an activity of

continuous improvement.

15.2 T O TAL QU ALITY MANA GEMENT (T QM) 471

this figure, the basic elements of this approach are consistent with the TQM-based safety

management system described above.

The integrated HSE management system that was set up put emphasis on the

wide range of elements shown in Table 15.5. The HSE policy in this table may seem

vague. The intention of incorporating and stating the company’s policies in its vision,

mission and value statements is to give the company/organization a committing and

visible direction/goal for its HSE efforts. For a particular company the policies will

normally be described more explicitly and may, for example, include the following

(Clement et al., 1996):

. Comply with all HSE laws, regulations and industry standards, and self-regulate where

there are no such prescriptive requirements.

. Exhibit socially conscious leadership and demonstrate excellent HSE performance.

. Seek to participate in developing HSE legislation, regulations and standards.

. Integrate HSE protection into every aspect of the business activities.

. Design and operate the company’s facilities followin g industry standar ds. Prevent

discharge of hazardous substances.

. Satisfactorily train employees and contractors, emphasizing individual responsibility

for sound HSE performance.

. Conserve natural resources by prudent management of emissions and discharges, and

by eliminating waste.

Figure 15.3. The process of introducingTQM. (Source: Clement et al.,1996.)

472 CHAPTER 15 SA FETY MANAGEM ENT

. Encourage employees to communicate within the company, as well as with the public,

regarding HSE matters.

. Work to resolve any pro blems created by past operations and practices.

. Ensure conformity with these policies through a comprehensive compliance

programme including audits.

Tabl e 15.5. HSE management system

Leadership and

commitment

Top management shall provide strong, visible leadership

and be fully involved

HSE shall be on the agenda in all management meetings

HSE is to be seen as a key business strategy

Accountability is of great importance

Policy HSE aspects shall be reflected or incorporated in the

company’s vision, mission and value statements

Organization The organization shall evolve from being functional to

becoming a team-based organization focused on asset

value optimization

HSE engineers/specialists shall be assigned to teams

The training programme shall be improved and

strengthened

Emergency response programmes shall be developed

Records shall be kept for documentation of plans,

management system, procedures, etc.

Implementation and

monitoring

Awareness and communications are key condition to success

Planned inspections and preventive maintenance

shall be carried out

Accidents, incidents and near-misses shall be investigated

Work rules and permits are to be used

Personal protective equipment shall be provided and used

Health hazard identification and evaluation shall be carried

out at regular intervals

Good change management is important

Environmental issues shall be identified and action plans

produced regularly

Establishing and maintaining good relations with external

stakeholders is of great priority

Measurement and

performance

The implementation shall be measured and the performance assessed

This process shall result in specific targets for the individual

business units

Audits and reviews It shall be assessed whether the HSE management system is

implemented effectively and according to the plan

Are the policy’s principles being fulfilled?

Are the objectives and performance measures achieved?

Are we in compliance with rules and regulations?

Establish areas for improvement

15.2 T O TAL QU ALITY MANA GEMENT (T QM) 473

Measurement and performance must be seen in relation to the activities of the diff erent

business units . The following list indicates typical performance measures for oil explora-

tion and production activities:

. Number of oil spill incidents

. Total volume of oil spilled

. Number of km of ro ad transport replaced with pipeline

. Area re-greened

. Km pipeline upgraded to present standard

. Volume of oily water and waste wat er discharged

. Hydrocarbon emission to air

. NO

x

and SO

x

emissions

The final element of the HSE management plan is auditing, which may be undertaken

both internally on a corporate scale, by the different business units, or by an independent

external auditor. With regard to which HSE-relevant elements of an organization

should be audited/reviewed, Clement et al. (1996) refer to a scheme developed by the

International Loss Control Institute (ILCI, 1995). According to this scheme the audit

elements are as follows:

1. Leadership and administration

2. Leadership training

3. Planned inspections and maintenance

4. Critical task analysis and procedures

5. Accident/incident/near-miss investigation

6. Task observation

7. Emergency preparedness

8. Intern al rules and work permits

9. Accident/incident/near-miss analysis

10. Knowledge and skill training

11. Personal protective equipment

12. Health and hygiene control

13. Programme evaluation

14. Engineering and change management

15. Personal communications

16. Group communications

17. General promotion

18. Hiring and placement

19. Materials and contractor management

20. Off-the-job HSE awareness

21. Environmental issue identification

22. Environmental action plan

23. Environmental performance monitoring and assessment

474 CHAPTER 15 SAFETY MANAG EMENT

24. Relations with external parties

25. Product stewardship

26. Agency permits, compliance reports and inspections

27. Off-site waste management

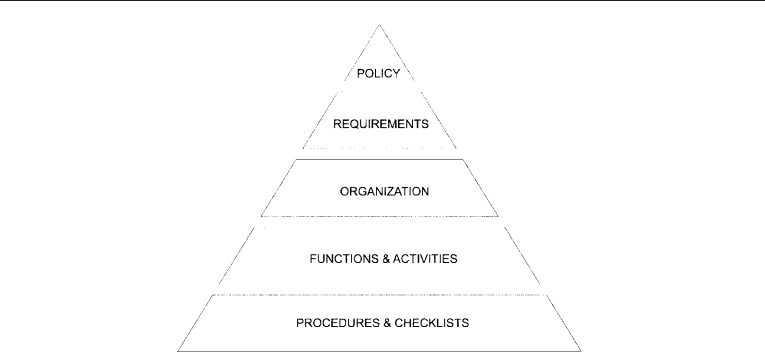

1 5.2.3 Quality Plan Structure

The quality plan, referring to the quality planning element of the ‘Juran Triology’ in

Figure 15.1, is the underlying basis for all quality and safety management. The key

elements of a quality plan are depicted in Figure 15.4. The starting points are the quality

policy and the requirements placed upon the organization. The plan itself consists of

careful descriptions of organizational, functional and procedural plan elements. Examples

of such quality plan elements are given in Table 15.6.

15.2.4 Quality Programme Structure

It is well known from experience that most organizations are able to define a qualit y plan

and establish the desirable standards that they want to achieve, but have greater difficulty

in living up to these standards as a part of the daily routine. In order to succeed in

improving quality (e.g. safety), a company needs not only a plan that defines the relevant

activities and quality objectives but also certain measur es that will transform the

organization into one that lives by its new policies and standards. This requires a more

rigorous approach in terms of a quality programme. The quality programme structure for

safety outlined in Figure 15.5 is more process-oriented than the quality plan previously

Figure 15.4. The quality plan.

15.2 T O TAL QU ALITY MANA GEMENT (T QM) 475