Krishnamurti Bhadriraju. The Dravidian Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

7.11

Other simple

finite

verbs

361

adding -m- to the stem to which the personal suffixes are added, ambo-m-a/-Ø (non-

future), ambo-ma-ke (future) (Mahapatra 1979: 174). Note that -ke has a tense meaning

in Malto and politeness meaning in Ku

.

rux, but it does seem to correspond to Proto-

Dravidian non-past

∗

-kk-. I cannot make any decision about Mundari -ko-insenkome,

cited by Hahn above.

18. Brahui: the suffix is -Ø/-a/-e in the singular. A ‘strengthened imperative’ is formed

by -ak. The plural is -bo/-ibo, e.g. bin- ‘to hear’: bin (sg), bin-bo (pl), bin-ak (extended

imperative). The prohibitive consists of the verbal base + -pa-/-fa- (neg) + -Ø (sg)/-bo

(pl), e.g. bis- ‘to bake’: bis-pa-bo ‘do not bake’, ba- ‘to come’ : ba-fa-bo ‘do not come’.

It appears that - p-/- f - is a reflex of non-past and -a- is the true negative sign in these

constructions.

7.11.2 The optative mood

The optative mood refers to a wish or curse by subjects in all persons (he/she/it/they/you

sg, pl) including (but not normally) even the first person (speaker), i.e. the optative may

refer to the second- or third-person subject. All literary languages and some non-literary

languages

have such constructions.

7.11.2.1 South Dravidian I

1. Tamil: in Old Tamil the optative is expressed by the suffixes -ka or -iya added to the

verbal stem with the subject stated separately, e.g. v¯a

.

z- ‘to flourish’: v¯a

.

z-ka or v¯a

.

z-iya

‘may (the subject) flourish!’ With the strong verbs the suffix is -kka, e.g. o

.

zi-kka ‘may

(one) destroy!’ An alternative usage is that of the optative of ¯aku ‘to be’, i.e. ¯aku-ka

after a finite verb, e.g. ceyt¯e

n¯a-ka ‘may I do!’ Another mechanism is the use of derived

nominals in -al/-tal as optative predicates, e.g. a

ri- ‘to know’: ari-tal ‘may (one) know!’,

cey-al ‘may one do!’ The negative optative verb consists of three constituents, the stem +

neg particle -a

r + optative -ka, e.g. cell- ‘to go’: cell-ar-ka ‘may (one) not go’, v¯ar-ar-ka

‘may (one) not come’.

16

Another construction is by the addition of the negative particle

-il followed by the optative -iyar, e.g. k¯a

.

n- ‘to see’: k¯a

.

n-il-iyar ‘may (one) not see!’

2. Malay¯a

.

lam: the construction corresponding to Old Tamil optative is used as a polite

imperative in Malay¯a

.

lam, e.g. a

ri- ‘to know’: arika ‘please know’, col- ‘to say’: coll-uka

‘please say’, pa

ra- ‘to tell’: para-kka ‘please tell’.

3. Toda: the optative suffix is -mo, e.g. k¨ıy- ‘to do’: k¨ıy-mo ‘let (one) do’, na

.

r- ‘to walk’ :

na

.

r-mo ‘let (one) walk’. This suffix looks similar to the South Dravidian II imperative

singular, -Vm.

4. Kanna

.

da: the suffixes -ge/-ke mark the optative added to the verb stem, e.g. k¯a

.

n-

‘to see’: k¯a

.

n-ge ‘may (one) see’, bar- ‘to come’: bar-ke ‘may (one) come!’ In Modern

Kanna

.

da the suffix is -ali, k¯a

.

n-ali ‘may (one) see’, bar-ali ‘may (one) come!’

16

The sandhi rule n → r/ k indicates that -ka was probably voiceless and doubled as -kk.

362 The verb

5. Tu

.

lu: the optative is expressed by the suffix -o

.

d¨ı, e.g. kalp- ‘to learn’: kalp-o

.

d¨ı ‘may

(one) learn’. This suffix seems to be related to the obligative -o

.

du, p¯ov-o

.

du ‘(one) must

go’.

7.11.2.2 South Dravidian II

6. Telugu: the optative is expressed in Old Telugu by -e

.

dun/-e

.

din or -tan/-tam added

to a verb

stem, e.g.

m¯ıku

1

´subhambu

2

kali-ge

.

dunu

3

/kalugu-tanu

3

‘may

3

good things

2

happen

3

to you

1

’. The optati

ve of the verb

agu- ‘to be’, i.e. k¯a-ka, can occur

after a

finite

verb in the optative mood, e.g. tirigi pu

.

t

.

tu-du-wu g¯a-ka ‘may you be reborn’.

7. Ko

.

n

.

da: the optative is formed by adding the optative suffix -i-/-pi- to the verb

stem before personal suffixes, mainly of the third person; there is one case in the second

singular, e.g. gume

.

n

.

dpa

.

n

.

d-i-d ‘may the pumpkin grow’, u

.

nzi son-i-r ‘let them eat and

go’, m¯a anar ibe ¯e

ru iyba-pi-r ‘let my elder brothers bathe here’. These constructions

are called

Desiderative-Permissi

ve by Krishnamurti (1969a: 282).

The optative suffix -ka/-kka in Tamil, Malay¯a

.

lam, Kanna

.

da and Telugu appears to be

a combination of non-past -k/-kk and the infinitive -a.

7.12 Durative or progressive (in present/past) in some languages

of South Dravidian

The verbs expressing the Durative (continuous action) in Tamil, Kanna

.

da, Tu

.

lu of South

Dravidian I and Telugu and Ko

.

n

.

da of South Dravidian II are apparently independent

innovations which do not reconstruct to Proto-South Dravidian.

7.12.1 South Dravidian I

It is said that in Middle Tamil (post-Ca˙nkam) -ki

nr-/-kir- emerged as the suffixes used

to express the present continuous, illustrated by the following paradigm, e.g. cey- ‘to

do’:

1sg cey-ki(

n)r-¯en 1pl cey-ki(n)r-¯om

2sg cey-ki(

n)r-¯ay 2pl cey-ki(n)r-¯ır(-ka

.

l)

3m sg cey-ki(

n)r-¯an

3f sg cey-ki(

n)r-¯a

.

l

3h pl cey-ki(

n)r-¯ar(-ka

.

l)

3neu sg cey-k(

n)r-atu 3neu pl cey-k(n)r-ana

The present adjective (relative participle) is formed by adding -a to the form ending in -ki

(n)

r-, e.g. cey-ki(n)r-a- ‘that is doing/done’. In Colloquial Tamil, the marker is -r-/-kr-,

cey-r-

˜

e ‘I am doing’, p¯a-kr-

˜

e ‘I am seeing’. In some Ca˙nkam classics the suffix sequence

-(k) i

r-p- occurs as an alternative marker of the future tense, e.g. kara- ‘to conceal’: kara-

kki

r-p-en ‘I will conceal’, k¯a

.

n-kir-p-¯ar ‘they will see’. Native grammarians consider

the underlying mor

ph to be -

kil-/-ki

n-. Middle and Modern Tamil present continuous

7.12

Durative or pro

gressive

363

(durative) -ki

nr-/-kir- is related to this (DVM: 244–5). If kil- ‘to be able’ is taken to be

the underlying morph, then the structure of this finite verb is different from others, i.e.

VSt + Aux (kil + tense -nt-) + (g)np. The only problem is that the filler of the slot

‘tense’ should then be the non-past -t- and not the past -nt-.

The Malay¯a

.

lam present-tense marker -unn- is derived from older -in

r-(<-kinr-)

which occurred as present-tense suffix around the tenth century (DVM: 249); the relative

participle is formed by adding the adjectival -a to -unn, e.g. Ma. v¯a

.

z-kin

r-a > v¯a

.

z-unn-a

‘that is living’.

Kanna

.

da has a periphrastic present tense formed by adding to the past stem the

inflected future finite verb of the auxiliary ¯a- ‘to be’: k¯e

.

l- ‘to hear’: k¯e

.

l-d-a-p(p)-em

‘we will hear’, which later became k¯e

.

l-d-a-h-em. In Modern Kanna

.

da such forms have

undergone a semantic change expressing ‘uncertainty /possibility’ with future reference,

e.g. id-d-(h)-¯enu ‘I may be’. Here older -ah- is lost. In Modern Kanna

.

da the present-

tense finite verb is formed by adding -utt- to the stem followed by (g)np suffixes, e.g.

1sg m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-¯ene ‘I am doing’, 1pl m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-¯eve, 2sg m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-i/¯ı, 2pl m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-¯ıri,

3m sg m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-¯ane,3fsgm¯a

.

d-ut(t)-¯a

.

le,3hplm¯a

.

d-ut(t)-¯are, 3neu sg m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-ade,

3neu pl m¯a

.

d-ut(t)-ave/-¯ave. The present participle is formed by adding -ut(t)u/-ut(t)¯a to

the verb stem, e.g. m¯a

.

d-ut(t)¯a ‘doing’. In Old and Medieval Kanna

.

da it was formed by

adding -ut(t)um, e.g. nagu- ‘to laugh’: nag-ut(t)um ‘laughing’, a

.

l- ‘to weep’: a

.

l-u(t)tum

‘weeping’.

Tu

.

lu has present–future and future tenses; the former is an innovation because it

is based on two non-past morphs, whereas the future is formed with one morph, e.g.

kal- ‘to learn’: kal-pu-v-ε ‘I am learning’ as opposed to future kal-p-e ‘I will learn’. The

present participle is formed by adding -ontu/-ondu to the past stem, e.g. kal-t-ontu /-ondu

(Brahmin and Common dialects) ‘learning’, tin- ‘to eat’: tin-d-ontu/tin-d-ondu ‘eating’.

The non-past adjective is formed by adding the tense marker -pub-/- p- in different social

dialects followed by the adjectival suffix -i, e.g. kal-pub-i /-p-i (Class I stems) ‘the one

who learns’; with others only -p-/-b-, e.g. t¯u- ‘to see’: t¯u-p-i ‘that which sees/will see’.

Another non-finite verb to express simultaneous action is -naga, whose origin is obscure,

e.g. kalpu-naga ‘while learning’, k¯e

.

n- ‘to ask’: k¯e

.

n-

.

naga ‘while asking’.

7.12.2 South Dravidian II

Old Telugu has -cu (n) as the present participle mark

er,

c¯eyu- ‘to do’: c¯eyu-cu (n) ‘doing’.

The durative verb is formed by adding to this the inflected forms of the verb un- ‘to

be’ followed by the past-tense marker -n- and (g)np suffixes. Here the past-tense suffix

has both present and past meanings, e.g. c¯eyu-c-un-n-a- adj [do-durative-be-past-adj]

‘the one doing in the past or present’. With the addition of demonstrative suffixes, we

derive c¯eyu-c-un-n-a-w

˜

¯a

.

du ‘the man who is/was/has been doing’ etc. At a later period

364 The verb

these became finite verbs like c¯eyu-c-un-n-

˜

¯a

.

du ‘he is/was/has been doing’. In Modern

Telugu -t¯u is the marker of the present participle and the durative verb is formed by

adding to the verb stem the non-past marker -t- followed by the inflection of un- ‘to be’,

c¯es- ‘to do’: c¯es-t¯u ‘doing’: c¯es-t-un-n-¯a

.

du ‘he is/was/has been doing’.

In Ko

.

n

.

da {-sin- ∼ -zin-} marks the durative aspect in finite and non-finite verbs.

This is a morph complex consisting of -si/-zi, the perfective participle marker, plus the

non-past-tense marker -n-, e.g. ven- ‘to listen’: ven-zin-an ‘he is listening’, ven-zin-i adj

‘the one hearing’, ven-zin-i

ŋ

‘as one is/was listening’, etc. The present continuous in Kui

is formed by adding the future-tense paradigm of the verb man- ‘to be’ to the present

participle in -pi, e.g.

.

d¯es- ‘to build’:

.

d¯es-pi man-Ø-amu ‘we are building’,

.

r¯u- ‘to plough’:

.

r¯u-i (loss of -v- < - p-) ma-Ø-i (loss of -n) ‘I am ploughing’. The present participle is

formed by adding to the stem -pi/-bi/-ki with sandhi variants. The consonants p ∼ b/k

encode the non-past, e.g. a

.

d- ‘to join’: a

.

t-ki ‘joining’, d¯ı- ‘to fall down’: d¯ıp-ki ‘falling

down’, ¯ar- ‘to call’: ¯ar-pi ‘calling’, jel- ‘to pull’: jel-bi ‘pulling’; in some classes of verbs

the present-participle marker is -ai, e.g. t¯ak- ‘to walk’: t¯ak-ai ‘walking’; -ji occurs after

some monosyllabic ones, tin- ‘to eat’: tin-ji ‘eating’, sal- ‘to go’: sa-ji ‘going’. In Kuvi

also the present tense is formed periphrastically by adding an inflected auxiliary man- ‘to

be’ in the future tense to the present participle of the main verb ending in -ci/-ji/-si/-hi,

e.g. t¯os- ‘to show’: t¯os-si manja

ʔ

i/ma

ʔ

i ‘I am showing’. Note that the non-finite verbs

ending in

∗

-ci/

∗

-cci mean perfective or past participles in Telugu, Gondi and Ko

.

n

.

da

unlike in Kui–Kuvi. The formation of the present tense in Pengo is idiosyncratic. It adds

-a at the end of the future-tense finite form to convert it into the present tense, e.g. hu

.

r-

‘to see’: hu

.

r-n-an ‘he will see’: hu

.

r-n-an-a ‘he is seeing’. This is apparently a recent

innovation by introducing an element of contrast, although in a slot that does not refer

to tense/aspect.

7.12.3 Central Dravidian

Kolami present–future marker -s/-sat/-at seems to have an element comparable to

∗

-ci

plus the non-past

∗

-tt. Naiki also has -at- as a future marker. The present-tense -m-in

Parji is traceable to PD

∗

-um.

7.12.4 Summary

Jules Bloch (1954: 77) considered OTa. ki(n)

r- as a verb meaning ‘to be’. Andronov

considers ki

nr- as the past stem of the root kil- ‘to be able’; alternatively, he thinks that

k-/kk- are non-past markers followed by the past stem of il- ‘to be’ (cited and supported

by DVM: 309–10). There is no evidence to support ki

r-oril- as verbs meaning ‘to

be’. Ta. and SD I il- is from PD

∗

cil- which means ‘to be not’ and not ‘to be’. Tamil,

Malay¯a

.

lam and Tu

.

lu have no present

participles; the meaning is conveyed by the past

participle of the reflexive auxiliary ko

.

l- ‘to take’, i.e. ko

.

n

.

tu added to the past participle

7.13

Serial verbs

365

of the main verb, e.g. Ta. ka

rru-k-ko

.

n

.

tu ‘learning’ from kal- ‘to learn’, past stem

∗

kal

+tt-. The Tu

.

lu present participle kal-t -ontu/-ondu seems to have the same kind of

structure.

It appears that Ka. -ut(t)um- and Te. -cun could be related, in which case the palatal

has to be older.

17

It is also tempting to compare OTe. -cun with Ko

.

n

.

da -si-n-/-zi-n- with

exactly the same meaning with a possible change of the front high vowel to the back one.

The only problem is that -ci-n- consists of two morphs, the perfective participle

∗

-ci plus

non-past

∗

-n; Telugu does not inherit the non-past -n like the other members of South

Dravidian II. Steever (1993: 91) argues that Ko

.

n

.

da durative verbs in -si-n-/-zi-n- are

derived by the Compound Contraction Rule from ki-zi ma-n-an → ki-zin-an,butKo

.

n

.

da

also has kizi manan ‘he has been doing’ (perfect continuous)

contrasting with

kizinan

‘he is doing’ (present continuous). In the case of the other pairs of finite verbs, which

Steever (1993: chs. 3, 4) has illustrated to have contracted into single finite verbs, the

older and later structures do not survive synchronically in the same language. We must

therefore take -sin-/-zin- as a complex morpheme innovated by Ko

.

n

.

da. Ka. -ut(t)um and

Mdn Te. -t¯u (durative markers) are apparently cognates.

7.13 Serial verbs

A peculiarity of Dravidian morphology and syntax is the existence in some clauses of

two finite verbs, called serial verbs. Steever (1993: 78–9) defines a serial verb ‘as a

complex form in which two or more formally finite verb forms enter into construction.

Both the main and auxiliary v

erbs in these constructions are

in

flected for tense and

subject-verb agreement in contrast to the typical Dravidian compound verb, in which

one form at most can be formally finite.’ These are reconstructible for Proto-Dravidian as

structural templates, filled in by synonymous, and not necessarily cognate, morphemes.

Telugu, a member of South Dravidian II and a literary language, has a past negative of

the following structure, Vst

1

-Neg-(g)np followed by Vst

2

-past tense-(g)np. Vst

2

is the

verb ¯a- ‘to be’ used as an auxiliary and Vst

1

is any verb, e.g. ceppu- ‘to tell’:

1sg cepp-a-n(u) ay-ti-ni (lit. I do not tell, I was), ‘I did not tell’

1pl ceppa-m(u) ay-ti-mi ‘we did not tell’

2sg cepp-a-w(u) ay-ti-wi ‘you (sg) did not tell’

2pl cepp-a-r(u) ay-ti-ri ‘you (pl) did not tell’

3m sg cepp-a-

.

d(u) ayy-e(n) ‘he did not tell’

3n-m sg cepp-a-d(u) ayy-e(n) ‘she/it did not tell’

3h pl cepp-a-r(u) ay-i-ri ‘they (h) did not tell’ etc.

Note that both the verbs are finite and they constitute a single predication. They cannot be

separated by other words or clitics and, therefore, are a single construction/compound

17

c (affricate) > t (dental) is more natural as an unconditioned sound change than t > c.

366 The verb

word and not a sequence of two words. Such constructions occur in Old Telugu and

Muria Gondi (Steever 1993: 113–15).

In the other South Dravidian II languages, similar finite verbs got telescoped into a

single finite verb. Steever (1993: ch. 4) has shown that similar finite verbs underlay the

emergence of single finite verbs in the past negative in South Dravidian II and Central

Dravidian languages, by a set of systematic historical changes, e.g. Ko

.

n

.

da: ki-

ʔ

e-n ‘he

does/will not do’ + ¯a-t-an ‘he was’ → ki-

ʔ

e-t-an ‘he did not do’. The last consonant

of the negative personal suffix -n and the first syllable of the auxiliary verb ¯a- ‘to be’

are lost. Steever has derived such synthetic past negative finite verbs from two analytic

verbs which were like those in Telugu, by a set of rules which he calls ‘Compound

Verb Contraction’: (1) the word boundary between the two verbs becomes a morpheme

boundary, (2) affix truncation leaves only the first vowel of the personal suffix, i.e. -e

of -en (3m sg), -i of -ider (2pl) of the first verb, (3) shortening of the first long vowel

of the auxiliary verb, i.e. ¯a-t-an becomes

∗

a-t-an, (4) vowel cluster simplification, i.e

-e + a- becomes -e. For deriving the correct forms he has used these rules sometimes in

different order. It is clear that vowel shortening and vowel cluster simplification can be

dispensed with. Instead

of the shortening of the

first vowel of the

auxiliary verb, we need

a rule of loss of the first syllable of the auxiliar

y; this rule will also appl

y to the auxiliary

verb which begins with a consonant, i.e. ma-n-an in Pengo and Kolami in which ma-

is lost. On the other hand, the vowel cluster simplification rule should normally result

in Dravidian in the second vowel surviving and the first vowel being lost. In the cases

illustrated by Steever, it is the preceding vowel that survives and the succeeding vowel

that goes. In terms of ‘Compound Verb Contraction’ Steever has succeeded in explaining

synthetic verbs like the present perfect in Pengo and the past negative in Ko

.

n

.

da and some

of the Central Dravidian languages. By extending the pattern he was able to explain the

verbs in Kui–Kuvi which include -ta- ∼ -tar-/-da- ∼ -dar-/-a- ∼ -ar- as the ‘transition

particle’ in clauses with transitive verbs incorporating such particles to encode direct

objects.

This pattern is also witnessed in some other South Dravidian

II languages.

Of all South Dravidian II languages, only Ko

.

n

.

da seems to have several types of serial

verbs which were treated as ‘compound verbs’ by Krishnamurti (1969a: 304–12). The

coordinate compound verbs have two or more underlying finite or non-finite verbs, e.g.

v¯a-t-an ‘he came’ + su

.

r-t-an ‘he saw’ → v¯a-t-asu

.

r-t-an ‘he came and saw’, maR-t-i

ŋ

‘after turning back’ + b¯es-t-i

ŋ

‘after looking back’ → maR-t-ib¯es-t-i

ŋ

‘as one turned

and looked back’. I stated clearly the rules underlying such formations. The coordinated

stems should have the same tense and person inflection in the finite and the same marker

in the non-finite. When the two verbs come together, only the first vowel of the marker

following the tense sign remains and the rest of the segments are lost: vand-it-ider ‘you

were tired’ + v¯a-t-ider ‘you came’ → vand-it-iv¯a-t-ider ‘you came tired’ (also see

maR-t-ib¯es-t-i

ŋ

above).

7.13

Serial verbs

367

There are also Subordinate Compounds in which the first stem is the main verb and

the second a member of a closed set of auxiliaries. These encode intensity and aspectual

contrasts, e.g. ek-t-an ‘he climbed’ +

.

ris-t-an ‘he left it’ → ek-t-a

.

ris-t-an ‘he climbed

up it’. Here

.

ris- is used as an auxiliary verb to signal ‘completion of action’. In the

formation of aspectual compounds the second stem is man- ‘to be’, g¯ur-it-an ‘he slept’ +

ma-R-an ‘he was’ → g¯ur-it-ama-R-an ‘he had slept’.

7.13.1 South Dravidian I

Old Tamil had va-nt-¯e

n ‘I came’ beside va-nt-an-en which were considered free variants,

the second involving an empty marker -a

n- following the past stem, called c¯ariyai in

traditional Tamil grammars. Steever (1993: 98–9) considers this the perfect-tense form

meaning ‘I have come’ and relates -a

n- to the auxiliary verb

∗

man-n-en (as in

∗

va-

nt-en

∗

man-n-en) without evidence for such a non-past finite form. In the absence of

comparative data from

any other member of South Dravidian

I, this proposal remains

unsubstantiated.

Also Rules of Degemination, Affix Truncation and ma- Deletion (note only m-is

deleted here) leading to

∗

man-n-en →

∗

ma-n-en →

∗

-a-n-en. Old Tamil also had serial

verbs with the negative verb al- as the auxiliary, e.g. va-nt-¯e

n all-¯en [come-past-I, be

not-I] ‘I did not come’ beside forms that have -al- alone as the negative marker, e.g.

k¯e

.

l-al-am ‘we will not listen’. The latter, according to me, is a straightforward negative

verb of the structure Vst-neg marker-(g)np. But again, Steever takes such constructions

as the result of a sequence of

two verbs, of which the main v

erb is said to lose the tense

and person markers followed by the negative verb

∗

al-am. Again, this kind of ‘affix

truncation’ of the main verb is unparalleled in the languages of South Dravidian I, and

hence suspicious.

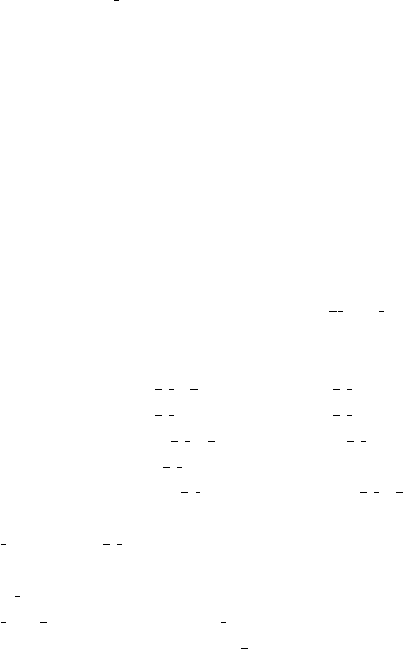

7.13.2 South Dravidian II

a. Ko

.

n

.

da (negative past

derivation), e.g.

ki- ‘to do’ Note that the rules

deriving the

composite form from two finite verbs are quite simple and systematic. They include

(1) replace the word-boundary between the two finite verbs with a morpheme boundary

(compound verb contraction); (2) truncate the personal suffix of the main verb to the first

vowel (or loss of all segments

except the

first one = vowel); (3) drop the first syllable

of the auxiliary verb. Note that the personal endings of the resultant past negative are

the allomorphs, which occur in non-negative verbs. This feature proves that there is

contraction of a negative non-past with a past verb ‘to be’ in the affirmative.

b. Pengo (present-perfect derivation) The present-perfect tense in Pengo has three

different realizations, which are said to be free-variants: (1) (Vst-Pst-PE) + na, (2)

(Vst-Pst-PE) + non-Pst-PE, (3) Vst-Pst-non-Pst-PE. The first two types apparently

368 The verb

T

able 7.20a.

Historical

derivation

of Kon

.

da

negative past

past of ¯a-

Negative non-past + ‘to be’ > Negative past

1sg ki-

ʔ

-e + (¯a)-t-a > ki-

ʔ

-e-t-a ‘I did not do’

1pl excl ki-

ʔ

-e(p + ¯a)-t-ap > ki-

ʔ

-e-t-ap ‘we did not do’

1pl incl ki-

ʔ

-e(

.

t + ¯a)-t-a

.

t > ki-

ʔ

-e-t-a

.

t ‘we (incl) did not do’

2sg ki-

ʔ

-i + (¯a)-t-i > ki-

ʔ

-it-i ‘you (sg) did not do’

2pl ki-

ʔ

-i(der + ¯a)-t-ider > ki-

ʔ

-it-ider ‘you (pl) did not do’

3m sg ki-

ʔ

-e(n + ¯a)-t-an > ki-

ʔ

-et-an ‘he did not do’

3m pl ki-

ʔ

-e(r + ¯a)-t-ar > ki-

ʔ

-et-ar ‘they (men)

∗

did not do’

3n-m sg ki-

ʔ

-e(d + ¯a)-t-ad > ki-

ʔ

-et-ad ‘she/it did not do’

3n-m pl ki-

ʔ

-u + ¯a)-t-e > ki-

ʔ

-ut-e ‘they (n-m) did not do’

∗

also ‘human’ in appropriate linguistic contexts.

Table 7.20b. Historical derivation of Pengo present perfect

Reconstruction of Pre-Pengo paradigm Pengo present-perfect tense

1sg

∗

hu

.

r-t-a

ŋ

man-n-a

ŋ

> 1sg hu

.

r-t-a(

ŋ

maØ)-n-a

ŋ

1pl excl

∗

hu

.

r-t-ap man-n-ap > 1pl excl hu

.

r-t-a(p maØ)-n-ap

1pl incl

∗

hu

.

r-t-as man-n-as > 1pl incl hu

.

r-t-a(s maØ)-n-as

2sg

∗

hu

.

r-t-ay man-n-ay > 2sg hu

.

r-t-a(ymaØ)-n-ay

2pl

∗

hu

.

r-t-ader man-n-ader > 2pl hu

.

r-t-a(der maØ)-n-ader

3m sg

∗

hu

.

r-t-an man-n-an > 3m sg hu

.

r-t-a(n maØ)-n-an

3m pl

∗

hu

.

r-t-ar man-n-ar > 3m pl hu

.

r-t-a(r maØ)-n-ar

3n-m sg

∗

hu

.

r-t-at man-n-at > 3n-m sg hu

.

r-t-a(tmaØ)-n-at

3f pl

∗

hu

.

r-t-ik man-n-ik > 3f pl hu

.

r-t-i(kmaØ)-n-ik

3n pl

∗

hu

.

r-t-i

ŋ

man-n-i

ŋ

> 3n pl hu

.

r-t-i(

ŋ

maØ)-n-i

ŋ

have the truncated non-past paradigm added to the past-finite verb; the last variant is

more synthetic since it has a complex tense morph (Pst-non-Pst) followed by personal

ending. The

last one conforms better to the word-formation rule of Dravidian.

All these

three variants are derived by Steever (1993: ch. 3) from two underlying serial verbs, the

past finite followed by the non-past finite with the base man- ‘to be’. The template in

table 7.20b is comparable to that of Ko

.

n

.

da past negative, although different auxiliaries

are used, hu

.

r- ‘to see’, man- ‘to be’.

As in the case of Ko

.

n

.

da the rules operate as follows: (1) replace word boundary by

a morpheme boundary (leading to contraction of two verbs into one); (2) a morpho-

phonemic rule drops the final -n of the root man- before another -n (non-past marker);

(3) drop all segments of the personal ending except the first vowel in the first verb;

(4) drop the first syllable of the auxiliary. As a consequence of the application of these

7.13

Serial verbs

369

rules, the resultant present perfect has a complex tense marker -tV- n which fits the word-

formation rule of Dravidian. Steever (1993: 81–2) derives the other variant paradigms

of Pengo by applying the rules in different order.

c. Gondi–Kui–Kuvi etc. Ko

.

n

.

da also has a present/past perfect or progressive con-

struction involving man- ‘to be’ as the auxiliary, e.g. g¯urita manan ‘he is sleeping’

< g¯ur-it-an ‘he slept’ and man-Ø-an ‘he is’, with affix truncation of the first verb, veyu

1

k¯ak-t-a(r)

2

ma-R-ar

3

‘(their) mouths

1

remained

3

open(ed)

2

’. In such compound con-

structions involving man- we do not find the deletion of the first syllable of the auxiliary

man- ‘to be’.

18

There are instances

of deletion of

man-/ma- in Kui, Kuvi

and Gondi

(Steever 1991: 91–3). It was noticed by Winfield (1928: 89) in Kui in the formation of

the present progressive as an allegro variant of the uncontracted construction, e.g. gip-ki

manji → gip-ki-nji ‘you are doing’ (present participle gip-ki + man-j-i ‘you are’), ta-sa

man-Ø-eru → ta-sa-n-eru ‘they have brought’. This form corresponds to Ko

.

n

.

da present

perfect ta-si man-Ø-ar ‘they

have brought

’, and

it also contrasts with

ta-sin-ar ‘they

are

bringing’. In Kuvi man- and its past stem mac- lose the root vowel in contraction, e.g.

kug-a ma-c-i → kuga-m-c-i ‘you had sat down’, kug-a man-Ø-e → kug-a-mn-e ‘she has

sat down’. In the Koya dialect of Gondi the present participle of a verb is combined with

an inflected form of min- ‘to be’ and is contracted to a single word, e.g. ¯u

.

d-¯or min-n-iri →

¯u

.

d-¯o-n-iri ‘you are seeing’ (¯u

.

d- ‘to see’).

7.13.3 Central Dravidian

Parji present perfect/progressive is also formed by serial verbs, i.e. the past finite + the

non-past (future) finite without any contraction, e.g. ve-

˜

n-ot m

˜

e-d-at ‘you have come’,

ve

.

rka e-

˜

n-er m˜e -d-ar (lit. pleasure become-past-3pl be-future-3pl) ‘they have become

happy’. These forms exactly match ‘morpheme for morpheme’ the reconstructed Pengo

present perfect (Steever 1993: 87).

19

Parji, in addition, uses the same form also as a

present progressive.

7.13.4 North Dravidian

Parallel constructions have been cited by Steever (1993: 93–6) from Ku

.

rux and Old

Tamil to show that serial verb constructions go back to Proto-Dravidian. In Ku

.

rux

Proto-Dravidian

∗

man- is replaced by a borrowed copular verb ra

ʔ

- ‘to be’ (Hin rahn¯a)

in the formation of present- and past-perfect tenses, e.g. ¯en

1

es-k-an

2

ra

ʔ

-ck-an

3

‘I

1

had

18

I have reservations in accepting the hypothesis of Steever (1993: 91) that the Ko

.

n

.

da durative

marker -zi-n-/-si-n- is the result of ma- deletion. It could simply be the result of adding the

non-past marker -n to the perfective marker -zi/-si, e.g. ki-zi ‘having done’, ki-zin-an ‘he is

doing’.

19

Note that Pre-Parji a becomes e before an alveolar consonant (see section 4.4.5).

370 The verb

broken (it)

2, 3

(lit. I

1

broke

2

, I remained

3

), coc-k-ar

1

ra-c-ar

2

‘they had dressed as men’

(lit. they dressed as men

1

(they) remained

2

). Steever (1993: 95–6) has shown that in

locative meaning manna ‘to be’ was replaced by borrowed ra

ʔ

-, but it remained in other

contexts.

7.13.5 Summary

Serial verbs,

i.e. two

finite verbs

of which the

first is the

main and the second the auxiliar

y,

can be reconstructed for Proto-Dravidian. There is evidence of the existence of such verbs

in Old Tamil, Old Telugu and other South Dravidian II languages, besides Parji of Central

Dravidian and Ku

.

rux of North Dravidian. In some of the languages of South Dravidian

II the serial v

erbs contract into one

finite verb with

the auxiliary suffering compression.

It is not certain if any language of South Dravidian I had such synthetic finite verbs.

7.14 Compound verb stems

Compound verb stems have the main verb as head of the construction. These are lexical

compounds for w

hich it is not possible to state

rules. The frequent ones are N

+ V

1

and

V

1

+ V

2

. In both the cases V

1

is the main verb; V

2

is a member of a closed set while V

1

is a member of an open set (any verb stem). Examples are given below from the literary

languages.

In Classical Tamil both the above types are found. I have taken here only those

compounds in which V

1

is not inflected, e.g. e

.

hku ‘to pull, comb (cotton)’ + uru ‘to

feel’ → e

.

hk-u

ru- ‘to feel the pull’, ari ‘to know’ + kil ‘to be able’ → ari-kil ‘to be

able to know’, tar- ‘to bring’: taru-kil- ‘to be able to bring’, ka

.

ti ‘to guard’ + ko

.

l ‘to

take hold of’ → ka

.

ti-ko

.

l- ‘to undertake to guard’, puku ‘to enter’ + tar ‘to bring’ →

puku-tar- ‘to make an entry into’, p¯o ‘to go’ + tar ‘to bring’ → p¯o-ttar- ‘to bring back’,

atir ‘to vibrate’ + pa

.

tu ‘to befall, suffer’ → atir-pa

.

tu- ‘vibrate violently’ (Rajam 1992:

501–20).

In the foregoing examples, Rajam says that V

1

has the ‘force’ of a verbal noun,

which does not seem to be correct on comparative grounds, cf. the verbs with tar-asV

2

in Kanna

.

da and Telugu. There are several examples of N + Vtype, e.g. al ‘darkness’ +

¯ar- ‘to be full’ → all-¯ar- ‘be full of darkness’, melku ‘cud’ + i

.

tu ‘put’ → melk-i

.

tu-

‘drop or let out cud’, k¯atal ‘love’ + cey ‘to make’ → k¯atal-cey- ‘to love’.

In literary Kanna

.

da ‘root compounds’ (Ramachandra Rao 1972: 152ff.) consist of

two-verb roots (V

1

+ V

2

) in which V

2

is sal- ‘to go’, tar- ‘to bring’, ¯e

.

z- ‘to rise’ etc., e.g.

ta

ri- ‘to cut’: tari-sal ‘to determine clearly’,

∗

ey- ‘to go’: ey-tar ‘to approach, reach’,

oge- ‘to emerge’: oge-tar- ‘to be born’, na

.

de- ‘to walk’: na

.

de-tar- ‘to approach’, p¯o- ‘to

go’: p¯o-tar- ‘to come’,

∗

j¯ır- ‘?to call’: j¯ır-¯e

.

z- ‘to scream, cry’, p¯ar- ‘to run’: p¯ar-¯e

.

z- ‘to

leap’. It is difficult to define, from availab

le source materials, how the meaning of the

second verb modifies the meaning of the first. These have tended to become idioms in