Kline R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

284 CORE TECHNIQuES

however, I assigned plausible standard deviations to each of the variables listed in Table

10.6. Taking this pedagogical license does not affect the overall fit of the model described

next. Instead, it allows you to reproduce this analysis or test alternative models for these

data with any SEM computer tool.

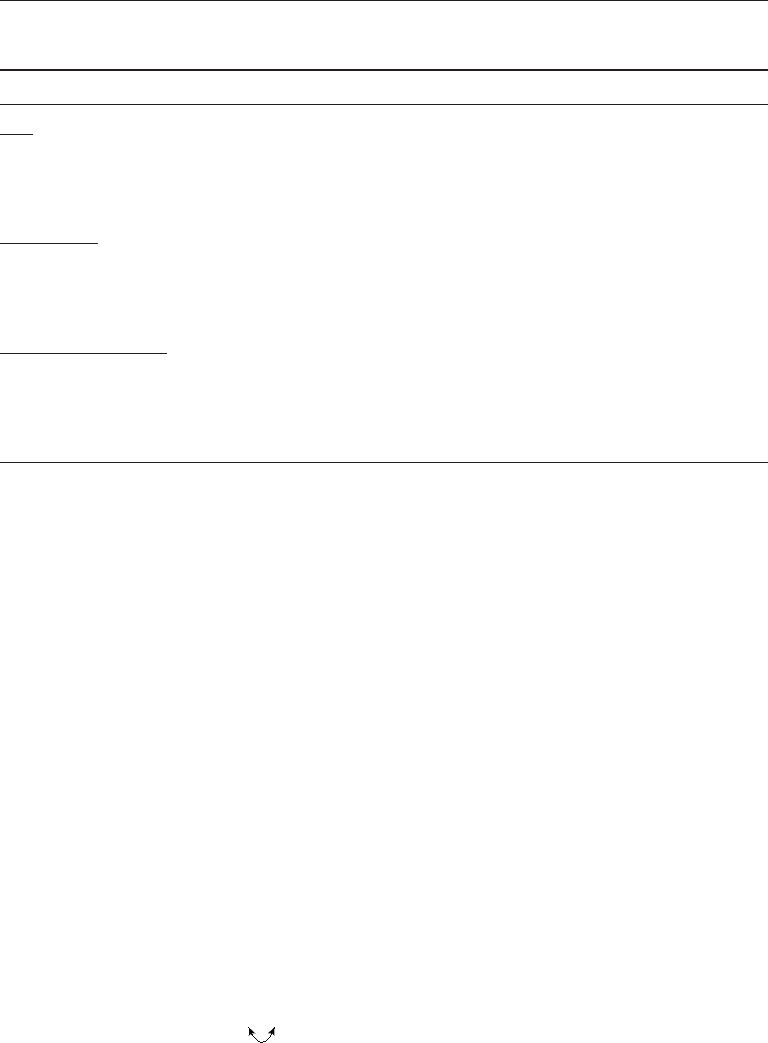

Suppose that the construct of risk is conceptualized for this example as a latent

composite with cause indicators family SES, parental psychopathology, and adolescent

verbal IQ. That is, high risk is indicated by any combination of low family SES, a high

degree of parental psychiatric impairment, or low adolescent verbal IQ. The intercor-

relations among these three variables are not all positive (see Table 10.6), but this is

irrelevant for cause indicators. Presented in Figure 10.7 is an example of an identified SR

model where a latent risk composite has cause indicators only. Note in the figure that the

risk composite emits two direct effects onto factors each measured with effect indicators

only, which satisfies the 2+ emitted paths rule. This specification identifies the distur-

bance variance for the risk composite. It also reflects the assumption that the association

between achievement and classroom adjustment is spurious due to a common cause

(risk). This assumption may not be plausible. For example, achievement probably affects

classroom adjustment. Specifically, students with better scholastic skills may be better

adjusted at school. But including the direct effect just mentioned— or, alternatively, the

disturbance correlation D

Ac

D

CA

—between these two factors in the model of Figure

10.7 would render it not identified.

I fitted the model of Figure 10.7 with a latent composite to the covariance matrix

based on the data in Table 10.6 with the ML method of EQS 6.1. The syntax and output

files for this analysis can be downloaded from this book’s website (p. 3). The analysis

converged to an admissible solution. Values of selected fit indexes are reported next:

taBle 10.6. Input data (Correlations and hypothetical standard deviations) for

analysis of a Model of risk as a latent Composite

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Risk

1. Parental Psychiatric

1.00

2. Low Family SES

.42 1.00

3. Verbal IQ

−.43 −.50 1.00

Achievement

4. Reading

−.39 −.43 .78 1.00

5. Arithmetic

−.24 −.37 .69 .73 1.00

6. Spelling

−.31 −.33 .63 .87 .72 1.00

Classroom adjustment

7. Motivation

−.25 −.25 .49 .53 .60 .59 1.00

8. Harmony

−.25 −.26 .42 .42 .44 .45 .77 1.00

9. Stability

−.16 −.18 .23 .36 .38 .38 .59 .58 1.00

SD

13.00 13.50 13.10 12.50 13.50 14.20 9.50 11.10 8.70

Note. These data are from Worland, Weeks, Janes, and Strock (1984); N = 158.

Structural Regression Models 285

2

M

χ

(22) = 75.421, p < .001

RMSEA = .124 (.094–.155)

GFI = .915; CFI = .941; SRMR = .041

These results indicate poor overall fit of the model to the data. Inspection of the corre-

lation residuals verifies this conclusion: several absolute residuals are close to or > .10.

These high-correlation residuals generally occurred between indicators of the achieve-

ment factor and the classroom adjustment factor (Figure 10.7). Specifically, the model

tends to underpredict these cross-factor correlations. This pattern is consistent with the

possibility that the coefficient for the direct effect of achievement on adjustment is not

zero. However, the only way to estimate this path is to respecify the model of Figure

10.7. Here are some possibilities:

1. Respecify the latent risk composite as a MIMIC factor with at least one effect

indicator, such as adolescent verbal IQ.

FIgure 10.7. An identified model of risk as a latent composite.

286 CORE TECHNIQuES

2. Drop the disturbance D

Ri

from the model in Figure 10.7, which would convert the

latent risk composite into a weighted combination of its cause indicators. Grace (2006)

argues that (a) error variance estimates for latent composites may have little theoreti-

cal significance in some contexts, and (b) the presence or absence of these error terms

should not by itself drive decisions about the inclusion of composites in the model.

3. Drop the risk composite from the model in Figure 10.7 and replace it with direct

effects from the three cause indicators to each of the two endogenous factors with effect

indicators.

Each respecification option just described would identify the direct effect between

achievement and classroom adjustment in Figure 10.7. Whether any of these options

makes theoretical sense is another matter, one that in a particular study would dictate

whether any of these respecifications is plausible.

Grace (2006, chap. 6) and Grace and Bollen (2008) describe many examples of the

analysis of models with composites in the environmental sciences. Jarvis, MacKenzie,

and Podsakoff (2003) and others advise researchers in the consumer research area—

and the rest of us, too—not to automatically specify factors with effect indicators only

because doing so may result in specification error, perhaps due to lack of familiarity

with formative measurement models. On the other hand, the specification of formative

measurement is not a panacea. For example, because cause indicators are exogenous,

their variances and covariances are not explained by a formative measurement model.

This makes it more difficult to assess the validity of a set of cause indicators (Bollen,

1989). The fact that error variance in formative measurement is represented at the con-

struct level instead of at the indicator level as in reflective measurement is a related prob-

lem. Howell, Breivik, and Wilcox (2007) note that formative measurement models are

more susceptible than reflective measurement models to interpretational confounding

where values of indicator loadings are affected by changes in the structural model. The

absence of a nominal definition of a formative factor apart from the empirical values of

loadings of its indicators exacerbates this problem. For these and other reasons, Howell

et al. conclude that (1) formative measurement is not an equally attractive alternative

to reflective measurement and (2) researchers should try to include reflective indica-

tors whenever other indicators are specified as cause indicators of the same construct,

but see Bagozzi (2007) and Bollen (2007) for other views. See also the special issue on

formative measurement in the Journal of Business Research (Diamantopoulos, 2008) for

more information about formative measurement.

An alternative to SEM for analyzing models with both measurement and structural

components is partial least squares path modeling, also known as latent variable

partial least squares. In this approach, constructs are estimated as linear combinations

of observed variables, or composites. Although SEM is better for testing strong hypoth-

eses about measurement, the partial least squares approach is well suited for situations

where (1) prediction is emphasized over theory testing and (2) it is difficult to meet the

requirements for large samples or identification in SEM. See Topic Box 10.1 for more

information.

Structural Regression Models 287

toPIC BoX 10.1

Partial least squares Path Modeling

A good starting point for outlining the logic of partial least squares path model-

ing (PLS-PM) is to consider the distinction between principal components analy-

sis versus common factor analysis. Principal components analysis analyzes total

variance and estimates factors as simple linear combinations (composites) of the

indicators, but common factor analysis analyzes shared (common) variance only

and makes an explicit distinction between indicators, underlying factors, and

measurement errors (unique variances). Of these two EFA methods, it is principal

components analysis that is directly analogous to PLS-PM.

The idea behind PLS-PM is based on soft modeling, an approach devel-

oped by H. Wold (1982) for situations in which theory about measurement is not

strong, but the goal is to estimate predictive relations among latent variables.

In PLS-PM, latent variables are estimated as exact linear combinations of their

indicators with OLS but applied in an iterative algorithm. This method is basically

an extension of the technique of canonical correlation but one that (1) explicitly

distinguishes between indicators and factors and (2) permits the estimation of

direct and indirect effects among factors. Similar to canonical correlation, indi-

cators in PLS-PM are weighted in order to maximize prediction. In contrast, the

goal of estimation in SEM is to minimize residual covariances, which may not

directly maximize the prediction of outcome variables.

The limited-information estimation methods in PLS-PM make fewer demands

of the data. For example, they do not generally assume a particular distributional

form, and the estimation process is not as complex. Consequently, PLS-PM can

be applied in smaller samples than SEM, and there are generally no problems

concerning inadmissible solutions. This makes the analysis of complex models

with many indicators easier in PLS-PM compared with SEM. It is also possible to

represent in PLS-PM either reflective or formative measurement but without the

strict identification requirements in SEM for estimating latent composites (Chin,

1998 ).

A drawback of PLS-PM is that its estimates are statistically inferior relative to

those generated under full-information estimation (e.g., ML in SEM) in terms of

bias and consistency, but this is less so in very large samples. Standard errors are

estimated in PLS-PM using adjunct methods, including bootstrapping. There are

generally no model fit statistics of the kind available in SEM. Instead, research-

ers evaluate models in PLS-PM by inspecting values of factor loadings, path

coefficients, and R

2

-type statistics for outcome variables. One could argue that

PLS-PM, which generally analyzes unknown weights composites, does not really

estimate substantive latent variables compared with SEM.

until recently, the application of PLS-PM was limited by the paucity of user-

cont.

288 CORE TECHNIQuES

InvarIanCe testIng oF sr Models

Just as in CFA, it is also possible to test invariance hypotheses when SR models are ana-

lyzed either over time or groups. Because SR models have both measurement and struc-

tural components, the range of invariance hypotheses that can be tested is even wider.

Listed next is a series of hierarchical SR models that could be tested for invariance in a

model trimming context where equality constraints are gradually added. This list is not

exhaustive, and it does not cover model building where the starting point is a restricted

model from which constraints are gradually released. Invariance testing across multiple

samples is emphasized next, but the same logic applies to analyzing an SR model over

time in a longitudinal design:

1. The least restrictive model corresponds to the configural invariance hypothesis

H

form

, which is tested by estimating the same SR model but with no cross-group equality

constraints. If H

form

is rejected, then invariance does not hold at any level, measurement

or structural.

2. Next test H

Λ

, the construct-level metric invariance hypothesis by imposing

equality constraints on each freely estimated factor loading across the groups. If H

Λ

is

rejected, then evaluate the less strict hypothesis H

λ

by releasing some, but not all, of the

equality constraints on factor loadings. Stop if all variations of H

λ

are rejected.

3. Given evidence for at least partial measurement invariance (i.e., H

Λ

or H

λ

is

retained), then it makes sense to test for invariance of structural model parameters.

For example, the hypothesis of equal direct effects, designated as H

B, Γ

, is tested by

imposing cross-group equality constraints on the estimates of each path coefficient. The

stricter hypothesis H

B, Γ, Ψ

assumes the equality of both direct effects and disturbance

friendly software tools. However, there are now a few different computer tools

for PLS-PM, some with graphical user interfaces. Presented on this book’s website

(p. 3) are links to other sites about graphical computer tools for PLS-PM, includ-

ing PLS-Graph, SmartPLS, and Visual-PLS. These programs are either freely avail-

able over the Internet or offered without cost to academic users after registration.

Temme, Kreis, and Hildebrandt (2006) describe the programs just mentioned

and other computer tools for PLS-PM. They note that graphical PLS-PM computer

tools rival their counterparts in SEM for ease of use, but PLS-PM programs do not

yet offer the range of analytical options. For example, most PLS-PM programs

analyze continuous indicators only and offer “classical” missing data techniques

only. On the other hand, some programs, such as Visual-PLS and SmartPLS, can

automatically estimate interactive effects of latent variables. See Vinzi, Chin,

Henseler, and Wang (2009) for more information.

Structural Regression Models 289

variances–covariances over groups, and the even stricter invariance hypothesis H

B, Γ, Ψ, Φ

also assumes equivalence of the variances and covariances of the exogenous factors. See

Bollen (1989, pp. 355–365) for more information. Tests for equal direct effects can also

be described as tests of moderation, that is, of interaction effects. Specifically, if magni-

tudes or directions of direct effects in the structural model differ appreciably across the

groups, then group membership moderates these direct effects. Chapter 12 deals with

the estimation of interaction effects in SEM.

rePortIng results oF seM analYses

With review of core structural equation models behind us, this is a good point to address

the issue of what to report. Listed in Table 10.7 are citations for works about reporting

practices, problems, and guidelines in SEM. Many of these works were cited in ear-

lier chapters, but they are listed all together in the table. Some of these articles con-

cern reporting practices in particular research areas (e.g., DiStefano & Hess, 2005), and

others are specific to particular techniques, such as CFA (e.g., Jackson, Gillaspy, & Purc-

Stephenson, 2009). Thompson’s (2000) “ten commandments” of SEM, summarized in

the table footnote, are also pertinent.

Presented next are recommendations for reporting SEM results organized by phases

taBle 10.7. Citations for Works about reporting Practices and guidelines for

Written summaries of results in structural equation Modeling

Work Comment

Boomsma (2000) General reporting guidelines

Breckler (1990) Review of studies in personality and social psychology

journals

DiStefano and Hess (2005) Review of CFA studies in assessment journals

Holbert and Stephenson (2002) Reporting practices in communication sciences

Hoyle and Panter (1995) General reporting guidelines

Jackson, Gillaspy, and

Purc-Stephenson (2009)

Review of CFA studies in psychology journals and specific

reporting guidelines

MacCallum and Austin (2000) Review of studies in psychology journals

McDonald and Ho (2002) General reporting guidelines

Raykov, Tomer, and Nesselroade

(1991)

Reporting guidelines for the psychology and aging area

Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, and

King (2006)

Reporting practices in educational research

Schreiber (2008) Reporting practices in social and administrative pharmacy

Shah and Goldstein (2006) Reporting practices in operations management research and

guidelines

Thompson (2000) “Ten commandments” of SEM

a

a

No small samples; analyze covariance, not correlation matrices; simpler models are better; verify distributional

assumptions; consider theoretical and practical significance, not just statistical significance; report multiple fit

statistics; use two-step modeling for structural regression models; consider theoretically plausible alternative

models; respecify rationally; acknowledge equivalent models.

290 CORE TECHNIQuES

of the analysis, from specification up through the tabulation and reporting of the results.

You can refer to these recommendations as a kind of checklist for preparing or evalu-

ating a written summary of SEM analyses. Study these suggestions carefully and use

them wisely; see also Schumacker and Lomax (2004, chap. 11) for related recommenda-

tions. You already know that there are many problems concerning the reporting of SEM

analyses in today’s research literature. By not repeating these common mistakes, you are

helping to improve the state of practice. This saying attributed to the psychologist and

philosopher William James is apropos here: Act as if what you do makes a difference; it

does.

specification

Describe the theoretical framework or body of empirical results that form the •

basis for specification of your model. Identify the particular research problem addressed

by your model and analysis. Explain why the use of SEM is relevant for this problem.

Give the rationale for directionality specifications. This includes both the mea-•

surement model and the structural model. For example, is standard reflective measure-

ment appropriate for describing the directionality of factor-indicator correspondences?

Or would the specification of formative measurement make more sense? For the struc-

tural model, clearly state the rationale for your hypotheses about effect priority, espe-

cially if your design is nonexperimental.

For presumed direct effects, state their expected directions, positive or negative. •

Give a diagram of your initial model. Represent all error terms and unanalyzed associa-

tions in the diagram. Make sure that the diagram is consistent with your description of

it in text.

Explain the rationale for any constraints to be imposed on parameter estimation. •

Relate these constraints to relevant theory, previous results, or aims of your study.

Outline any theoretically plausible alternative models. State the role of these •

alternative models in your plan for model testing. Describe this plan (e.g., testing nested

models vs. comparing nonhierarchical models).

In multiple-sample analyses, state the particular forms of invariance to be tested •

and in what sequence (i.e., model building or trimming).

Identification

Tally the number of observations and free parameters in your initial model. State •

(or indicate in a diagram) how latent variables are scaled. That is, demonstrate that nec-

essary but insufficient conditions for identification are met.

Comment on sufficient requirements for identifying the type of structural equa-•

tion model you are analyzing. For example, if the structural model is nonrecursive, is

the rank condition sufficient to identify it? If the measurement model has error covari-

ances, does their pattern satisfy the required sufficient conditions?

Structural Regression Models 291

data and Measures

Clearly describe the characteristics of your sample (cases) and measures. State •

the psychometric properties of your measures, including evidence for score reliability

and validity. Report values of reliability coefficients calculated in your sample. If this is

not possible, then report the coefficients from other samples (reliability induction), but

explicitly describe whether those other samples are similar to your own.

If the sample is archival—that is, you are fitting a structural equation model •

within an existing data set—then mention possible specification errors due to the omis-

sion of relevant measures in this sample.

Verify the assumption of multivariate normality in your sample when using nor-•

mal theory estimators. For example, report values of the skew index and kurtosis index

for all continuous outcome variables.

Describe how data-related complications were handled. This includes the extent •

and strategy for dealing with missing observations, how apparent extreme collinearity

was dealt with, and the use of transformations, if any, to normalize the data.

Clearly state the type of data matrix analyzed, which is ordinarily a covariance •

matrix. Report this matrix—or the correlations and standard deviations—and the

means in a table or an appendix. To save space, reliability coefficients and values of skew

and kurtosis indexes can be reported in the same place. Give the final sample size in this

summary. You should report enough summary information so that someone else could

take your model diagram(s) and data matrix and reproduce your analyses and results.

Verify that your data matrix is positive definite.•

estimation and respecification

State which SEM computer tool was used (and its version), and list the syntax for •

your final model in an appendix. If the latter is not feasible due to length limitations,

then tell your readers how they can access your code (e.g., a website address).

State the estimation method used, even if it is default ML estimation. If some •

other method is used, then clearly state this method and give your rationale for selecting

it (e.g., some outcome variables are ordinal).

Say whether the estimation process converged and whether the solution is admis-•

sible. Describe any complications in estimation, such as failure of iterative estimation

or Heywood cases, and how these problems were handled, such as giving the computer

new start values or increasing the default limit on the number of iterations.

Always report the model chi-square and its • p value for all models tested. If the

model fails the chi-square test, then explicitly state this result.

Never conclude that model fit is satisfactory based solely on values of fit statistics, •

which only indicate overall model–data correspondence. Along the same lines, do not

rely on “golden rules” for approximate fit indexes to justify the retention of a particular

model. This is especially true if the model chi-square test was failed.

Describe model fit at a more molecular level by conveying diagnostic information •

292 CORE TECHNIQuES

about patterns of correlation residuals, standardized residuals, or modification indexes.

For a smaller model, report the correlation residuals and standardized residuals. The

point is to reassure your readers that your model has acceptable fit on both a global level

and at the level of pairs of observed variables.

When a model is respecified, explain the theoretical basis for doing so. That •

is, how are the changes justified? Indicate the particular statistics, such as correlation

residuals, standardized residuals, or modification indexes, consulted in respecification

and how the values of these statistics relate to theory.

Clearly state the nature and number of respecifications such as, how many paths •

were added or dropped and which ones?

If the final model is quite different from your initial model, reassure your read-•

ers that its respecification was not merely chasing sample-specific (chance) variation. If

there is no such rationale, then the model may be overparamterized (good fit is achieved

at the cost of too many parameters).

When testing hierarchical models, report the information just described for all •

candidate models. Also report results of the chi-square difference test for relevant com-

parisons of hierarchical models.

When testing SR models, establish that the measurement model is consistent •

with the data before estimating versions with alternative structural models.

tabulation

Report the parameter estimates for your final model (if a model is retained). This •

includes the unstandardized estimates, their standard errors, and the standardized esti-

mates. In a multiple-sample analysis, describe how the standardized estimates were

derived in your SEM computer tool.

Do not indicate anything about statistical significance for the standardized •

parameter estimates unless you used a method, such as constrained estimation, that

generates correct standard errors in the standardized solution.

Comment on whether the signs and magnitudes of the parameter estimates make •

theoretical sense. Look for potential “surprises” that may indicate a suppression effect

or other unexpected results.

Report information for individual outcome variables about predictive power, such •

as

2

smc

R

or a corrected-R

2

for endogenous variables in a nonrecursive structural model.

Interpret effect sizes (e.g., standardized path coefficients, •

2

smc

R

) in reference to

results expected in a particular research area.

avoid Confirmation Bias

Explicitly deal with the issue of equivalent models. Generate some plausible •

equivalent versions of your final model and give logical reasons why your preferred

model should be favored over equivalent versions.

It may also be possible to consider alternative models that are not equivalent but •

are based on the same observed variables and fitted to the same data matrix. Among

Structural Regression Models 293

alternative models that are near-covariance equivalent, give reasons why your model

should be preferred.

If a structural model was tested, do • not make claims about verifying causality,

especially if your design is nonexperimental and thus lacks design elements, such as

control groups or manipulated variables, that support causal inference.

Bottom lines and statistical Beauty

If no model was retained, then explain the implications for theory. For example, •

in what way(s) could theory be incorrect, based on your results?

If a model is retained, then explain to your readers just what was learned as a •

result of your study. That is, what is the substantive significance of your findings? How

has the state of knowledge in your area been advanced? What comes next? That is, what

new questions or issues are posed?

If your sample is not large enough to randomly split and cross-validate your anal-•

yses, then clearly state this as a limitation. If so, then replication is a necessary “what

comes next” activity. Until then, restrain your enthusiasm about your model.

suMMarY

The evaluation of a structural regression model is essentially a simultaneous path analy-

sis and confirmatory factor analysis. Multiple-indicator assessment of constructs is rep-

resented in the measurement portion of a structural regression model, and presumed

causal relations are represented in the structural part. In two-step analyses, a structural

regression model is respecified as a confirmatory factor analysis model in the first step.

An acceptable measurement model is required before going to the second step, which

involves testing hypotheses about the structural model. The researcher should also con-

sider equivalent versions of his or her preferred structural regression model. Equiva-

lent versions of the structural part of a structural regression model can be generated

using the same rules as for path models, and equivalent measurement models can be

created according to the same principles as for CFA models. The specification of reflec-

tive measurement wherein effect indicators are specified as caused by latent variables

is not appropriate in all research problems. An alternative is formative measurement

where indicators are conceptualized as causes of composites. The evaluation of struc-

tural regression models represents the apex in the SEM family for the analysis of covari-

ances. The next few chapters in Part III consider some advanced methods, starting with

the analysis of means. How to avoid fooling yourself with SEM is considered in the last

chapter (13), which may be the most important one in this book.

reCoMMended readIngs

Howell, Breivik, and Wilcox (2007) compare assumptions of standard reflective measurement

with those of formative measurement. You can learn more about formative measurement in a