Keyfitz N., Caswell H. Applied Mathematical Demography

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

11.3. Age-Specific Traits From Stage-Specific Models 265

0 20 40 60 80 100

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

A

g

e class

Frequency

Stage 2

Stage 3

Stage 4

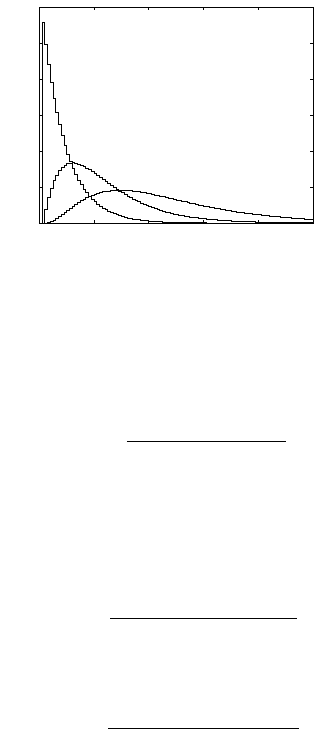

Figure 11.6. The stable age-within-stage distributions for killer whales, for stages

N

2

–N

4

. Stage 1 (yearlings) is composed entirely of individuals in age class 1, and

is not shown.

or, in discrete time

µ

1

=

i

i

.

i−1

j=1

P

j

F

i

i

.

i−1

j=1

P

j

F

i

, (11.3.43)

wherewedefine

.

0

j=1

P

j

=1.

3. The mean age

¯

A of the parents of the offspring produced by a

population at the stable age distribution:

¯

A =

∞

0

xe

−rx

l(x)m(x) dx

∞

0

e

−rx

l(x)m(x) dx

, (11.3.44)

or, in discrete time

¯

A =

i

iλ

−i

.

i−1

j=1

P

j

F

i

i

λ

−i

.

i−1

j=1

P

j

F

i

. (11.3.45)

The denominator in both of these equations is the characteristic equa-

tion, and is thus equal to 1. Note that µ

1

canbeobtainedfrom

(11.3.45) by setting λ = 1. Thus, in a stationary population, µ

1

=

¯

A.

In human populations T ≈ (µ

1

+

¯

A)/2, and all three measures are very

similar (Coale 1972). In species with higher mortality rates and/or rates of

increase farther from 1, the differences among these indices of generation

time are likely to be greater.

The discrete versions of T , µ

1

,and

¯

A can be calculated directly from a

Leslie matrix for an age-classified population. The methods of this chapter

let us calculate them from stage-classified models. The time required to

increase by a factor R

0

can be calculated directly as T =logR

0

/ log λ

1

,

where R

0

is calculated according to Section 11.3.4. For example, in the

266 11. Markov Chains for Individual Life Histories

killer whale example, R

0

=2.0131 and λ

1

=1.0254, so T =27.85 years,

which compares well with the value of 24.8 years calculated by Olesiuk et

al. (1990) from an age-classified model.

Both

¯

A and µ

1

can be calculated using the age-specific survival and

fertility values obtained from the stage-classified matrix

††

(see Sections

11.3.1 and 11.3.2). In the case of the killer whales, this calculation yields

¯

A =23.67 and µ

1

=32.18. Since the population is increasing, the stable

age distribution is skewed to younger ages than is a cohort; thus

¯

A<µ

1

.

Also note that (

¯

A + µ

1

)/2=27.93, which is close to T =27.85, as noted

by Coale (1972) for age-classified models for humans.

11.3.6 Age-Within-Stage Distributions

The individuals within a stage may have arrived there by many different

pathways, and thus be of many different ages. We can calculate the stable

age distribution within each stage and the stable stage distribution within

each age class.

Let λ be the dominant eigenvalue of A = T + F and let w be the corre-

sponding right eigenvector. Suppose that the population has been growing

at the rate λ for a long time, so that the age and stage distributions have

stabilized. We observe the population at some time t. Because the stage

distribution is stable, the births at t are proportional to Fw. The births at

time t − a were proportional to λ

−a

Fw. Those individuals are now in age

class a + 1, with a stage distribution proportional to λ

−a

T

a

Fw.

Create a rectangular array

X =

/

Fw λ

−1

TFw λ

−2

T

2

Fw ···

0

.

The columns of X correspond to ages, the rows to stages. Thus row i of

X, normalized to sum to 1, gives the stable age distribution within stage

i. Column j, normalized to sum to 1, gives the stable stage distribution

within age class j.

In the killer whale example, λ =1.0254 and

w =

⎛

⎜

⎜

⎝

0.0370

0.3161

0.3229

0.3240

⎞

⎟

⎟

⎠

.

††

These measures are not well defined when there are multiple types of newborn

individuals. Cochran and Ellner (1992) suggest a way to calculate them using fertility

weighted by reproductive value, but it is not clear to me that the resulting model actually

corresponds to that underlying the definitions of

¯

A and µ

1

.

11.3. Age-Specific Traits From Stage-Specific Models 267

The first few columns of X are given by

Age class

Stage

12345···

1 0.03790000···

2

00.0361 0.0321 0.0285 0.0253 ···

3

000.0026 0.0047 0.0064 ···

4

0000.0001 0.0003 ···

Scaling so that the rows sum to one gives

Age class

Stage

12345···

1 1.00000000···

2

00.1115 0.0991 0.0880 0.0782 ···

3

000.0078 0.0143 0.0195 ···

4

0000.0004 0.0010 ···

Thus all the stage-1 (yearling) individuals are in age class 1, which is to be

expected since they spend only a single time step there. The distributions

for stages N

2

–N

4

are shown in Figure 11.6. They are not unreasonable,

and where they seem a little strange (e.g., mature adults still appreciably

frequent at ages greater than 50, postreproductive females beginning to

appear before age 10) the discrepancies are obvious consequences of the

stage classification. Because there are only three stages before the postre-

productive stage, some individuals will become postreproductive after only

three iterations. Similarly, because there is a self-loop on stage 3, some

individuals will remain there indefinitely.

Boucher (1997) used essentially identical calculations to compare the

stable age-within-stage distributions from 10 models (turtles, trees, killer

whales, herbaceous plants, corals). He found that, as in Figure 11.6, the

age-distribution within later stages becomes lower, more symmetric, and

flatter. The skewness and the kurtosis of the age-within-stage distribution

decreased, roughly exponentially, from early to later stages.

12

Projection and Forecasting

All statistical facts refer to the past. The United States Census of April

1970 counted 203 million of us, but no one knew this until the following

November, and the details of the count were published over the course of

years. The census differs only in degree from stock market prices, which are

hours old before they appear in the daily press. There are no exceptions—

not even statistics of intentions—to the rule that all data are to some degree

obsolete by the time they reach us.

On the other hand, all use of data refers to the future; the business

concern proposing to set up a branch in a certain part of the country

consults the census but is interested in what it tells only as an indication

of what will come in the future. The branch plant, or a school or hospital,

may take 3 years to build and will be in existence over the following 30

years; whether the decision to build was wise depends on circumstances

between 3 and 33 years hence, including the number and distribution of

people over that period.

12.1 Forecasting: Both Unavoidable and

Impossible. Past Data, Present Action, and

Future Conditions of Payoff

That all data refer to the past and all use of data to the future implies a line

between past and future drawn at “now.” Without continuities that make

12.1. Unavoidable and Impossible 269

possible extrapolation across that line statistical data would be useless,

indeed the very possibility of purposeful behavior would be in doubt.

The separation between a past census and the future in which action will

be implemented is not only the instance of now, but also a finite period

of time that includes the interval from enumeration of the census to pub-

lication of its results, the interval between their publication and the use

of them in making a decision, and the interval between the decision and

its implementation. The slab of time separating past data on population

and the start of operation of a factory or school or telephone exchange

decided upon by projecting these data can easily be a decade or more.

Prediction often consists in examining data extending several decades back

into the past and inferring from them what will happen several decades in

the future, with one decade of blind spot separating past and future.

Since our knowledge of population mechanisms is weak, moreover, pre-

dictions or forecasts, more appropriately and modestly called projections,

must involve some element of sheer extrapolation, and this extrapolation

is from a narrow database. Below the observations is an historical drift in

underlying conditions that makes the distant past irrelevant to the future.

If in the nineteenth century fluctuations in population were caused largely

by epidemics, food scarcities, and other factors, and if now these factors

are under better control but even larger changes in population are caused

by parental decisions to defer or anticipate births, then carrying the series

back through the nineteenth century will not be of much help in present ex-

trapolations to the future. Thus, even supposing the continuity that makes

forecasting possible in principle, the volume of past data enabling us to

make a particular forecast is limited. Moreover, this intrinsic scarcity of

relevant data is in addition to the shortcomings of past statistical collec-

tions. For such reasons some of those who are most knowledgeable refuse

to take any part in forecasting.

Yet ultimately the refusal to forecast is absurd, for the future is implicitly

contained in all decisions. The very act of setting up a school on one side

of town rather than the other, of widening a road between two towns, or

of extending a telephone exchange is in itself a bet that population will

increase in a certain way; not doing these things is a bet that population

will not increase. In the aggregate implicit bets, known as investments,

amount to billions of dollars each year. The question is only who will make

the forecast and how he will do it—in particular, whether he will proceed

intuitively or use publicly described methods. As Cannan (1895) said in

the very first paper using the components method of forecasting, “The

real question is not whether we shall abstain altogether from estimating

the growth of population, but whether we shall be content with estimates

which have been formed without adequate consideration of all the data

available, and can be shown to be founded on a wrong principle.”

In any concrete investment decision, the bet on population is combined

with a bet on purchasing power, on preferences for one kind of goods rather

270 12. Projection and Forecasting

than another, on technology as it affects alternative methods of production.

The component of the bet that is our interest in this book, population, is

somehow incorporated into a package of bets.

12.1.1 Heavy Stakes on Simultaneous Lotteries

A school construction program, for example, cannot be based on population

forecasts alone; it requires participation rates as well—what fraction of the

school-age population will want to attend school. These two elements both

change over time. During the 1960s, for example, United States population

and participation rates both rose among youths of college age. Those 20 to

24 years of age numbered 10,330,000 in 1960 and 15,594,000 in 1970, a rise

of 51 percent; the fraction enrolled at school went from 13.1 to 21.5 percent,

a rise of 64 percent over the same decade. The ratio for the population being

1.51, and the ratio for participation 1.64, the combined effect of these two

factors was the product of 1.51 and 1.64 or 2.48, equal to the ratio of 1970

to 1960 enrollment. Planning a school for any future period is in effect

taking out a package of at least two lottery tickets.

Sometimes a movement of one of the factors counteracts a movement of

the other, and in that case one turns out to be better off with the package

bet than one would have been with either component alone. New college

enrollments have started to decline in some parts of the country, while en-

trants are still the cohorts of the 1950s when births were constant or rising.

Thus so far the two offset each other. But if decline in the participation

rate continues through the 1980s, when the college-age cohorts will decline,

the drop in attendance will be rapid.

It is often said that population forecasts should be made in conjunction

with forecasts of all the other variables with which population interacts.

The state of the economy is certainly related to population: marriages, and

hence first births, will be numerous in good times, and will be few when

incomes are low and unemployment high. This is the case in advanced

countries; in poor countries births will fall with the process of economic

development, and the sooner the rise in income the sooner will be the fall

in births, at least on the theory that has been dominant. In both rich and

poor countries shortages of land, energy, minerals, food, and other resources

will, through different mechanisms, restrict population growth.

Our present capacity to discern such mechanisms is embarrassingly lim-

ited, for reasons briefly explored in Section 17.5. At best we can suggest

which factors may be related to which other ones, but even the direction

of effect, let alone quantitative knowledge of the relations, is still largely

beyond us. That is why most of the work reported in this chapter, like most

population projection as practiced, concentrates on demographic variables

alone.

12.1. Unavoidable and Impossible 271

12.1.2 Projection as Distinct from Prediction

The preceding chapters, mostly based on stable theory, have also been con-

cerned with projection in a population closed to migration, but always with

long-term projection. They answered a variety of forms of such questions

as: what will be the ultimate age distribution if present birth and death

rates continue, or what difference will it make to the ultimate rate of in-

crease if the birth rate to women over 35 drops permanently to half its

present value, everything else remaining unchanged? The long-run answers

are usually simpler than the medium-term ones of population projection.

The questions asked in the preceding chapters were so clearly of the

form, “What will happen if ... ?” that there was no need to stress the

conditional character of the statements referring to the future. Medium-

term population projection offers the appearance of prediction, but the

detailed reference to the future need not alter the conditional character

of the numbers produced. Section 12.2 begins the treatment of projection,

while Section 12.5 concerns prediction or forecasting, that is, statements

intended to apply to a real rather than to a hypothetical future, but in fact

the two topics are inseparable.

A projection is bound to be correct, except when arithmetic errors make

the numbers constituting its output inconsistent with the assumptions

stated to be its input. On the other hand, a forecast is nearly certain to

be wrong if it consists of a single number; if it consists of a range with a

probability attached, it can be correct in the sense that the range straddles

the subsequent outcome the stated fraction of times in repeated forecast-

ing. A probability can—indeed, should—be attached to a forecast, whereas

a probability is meaningless for a (hypothetical) projection.

The distinction between projection and forecasting (Keyfitz 1972a), has

become critically important in population ecology, where environmental

fluctuations and density-dependence make forecasting even more difficult,

but projection even more useful. In particular, a projection can be inter-

preted as providing information about the current situation rather than

future population (“conditions here and now are such that if they were

somehow held constant, the population would grow at this rate, with this

structure, etc.”). Such conclusions are particularly valuable in comparative

studies (see Section 13.4).

Despite the apparently sharp distinction, projections put forward under

explicit assumptions are commonly interpreted as forecasts applying to the

real future. Does the intention of the authors or the practice of the users

determine whether projection or forecasting has occurred in a particular

instance? Insofar as the assumptions of a projection are realistic, it is in-

deed a forecast. Those making projections do not regard all assumptions as

equally worth developing in numerical terms and presenting to the public,

but at any given moment they select a set regarded as realistic enough to

be of interest to their readers. When they change to a different set, users

272 12. Projection and Forecasting

suppose that the old assumptions have become unrealistic in view of cur-

rent demographic events. More will be said later about the dangers and

excitements of forecasting; the section immediately following deals with

projection.

12.2 The Technique of Projection

Projection in demography is calculating survivors down cohort lines of

those living at a given point in time, calculating births in each successive

period, and adding a suitable allowance for migration. Of the various ways

of looking at population dynamics, the one most convenient for the present

purpose is the matrix approach (Chapter 7). Such calculations were used,

before Leslie (1945) expressed them in matrix form, by Cannan (1895),

Bowley (1924), and especially Whelpton (1936).

Survivorship. Within the supposedly homogeneous subpopulation the first

step is to convert the death rates that are assumed to apply at each period

in the future into a life table, or else directly assume a life table for each

future period. The column used for the purpose is the integral

5

L

x

=

5

0

l(x + t) dt,

which in general varies over time as well as over age.

If the population at the jumping-off point of the projection is

5

N

(0)

x

for

ages x =0, 5, 10,..., the population 5 years older and 5 years later may be

approximated as

5

N

(5)

x+5

=

5

N

(0)

x

5

L

x+5

5

L

x

. (12.2.1)

For changing rates a new life table would be assumed operative at each

future 5-year interval and applied as in (12.2.1). By this means the popu-

lation would be “survived” forward until the cohorts of the initial period

were all extinguished.

Expression (12.2.1) is not exact even if the life table is appropriate, un-

less the distribution within the age group (x, x + 5) happens to be exactly

proportional to the stationary population l(x+t), 0 t 5. If the popula-

tion is increasing steadily at rate r, the distribution within the age interval

will be proportional to e

−rt

l(x + t); and the greater r is, the more the pop-

ulation will be concentrated at the left end of the age interval. Being on the

average younger within each age interval, it will average somewhat higher

survivorship from one age interval to the next in the part of the span of

life where mortality is rising with age. [Using the Taylor expansion method

of Section 2.2 find a formula for the small addition to (12.2.1) to allow for

12.2. The Technique of Projection 273

Table 12.1. Population and life table data for estimating survivorship of females

70–74 years of age, England and Wales, 1968

Age

5

N

x

5

L

x

l

x

65 1,280,500 391,456 82,172

70 1,033,400 339,660 73,827

75 753,600 265,710 61,324

Source: Keyfitz and Flieger (1971),

pp. 152, 154.

this, and calculate its amount from the data of Table 12.1. A different form

of correction is given as (11.1.16) in Keyfitz (1968, p. 249).]

Reproduction. To estimate the births of girl children to women in each 5-

year age interval we need a set of age-specific birth rates, say F

x

, for ages x

to x + 4 at last birthday (for brevity omitting the prescript). The F

x

might

be obtained from past experience, over 1 calendar year, say, of observed live

female births

5

B

x

to women of exact age (x, x+5). If midperiod population

corresponding to these births numbered

5

N

x

,thenF

x

=

5

B

x

/

5

N

x

.

In the first time period we begin with

5

N

(0)

x

women aged x to x+4 at last

birthday and, applying (12.2.1), end with

5

N

(0)

x−5

(

5

L

x

/

5

L

x−5

) women in this

age class. Within the age class, an estimate of the mean surviving women

(or the average exposure per year during the 5 years) is the average of these

two numbers. Multiplying this average by 5 yields the total female exposure

to conception during the 5 years. Multiplication of the total exposure by

F

x

yields the expected births to women aged x to x +4(l

0

= 1):

5

2

5

N

(0)

x

+

5

N

(0)

x−5

5

L

x

5

L

x−5

F

x

,x= α, α +5,...,β−5. (12.2.2)

However, since we are interested in the population aged 0 to 5 rather than

the number of births, we must multiply (12.2.2) by

5

L

0

/5andsumoverall

the fertile ages between α and β:

5

N

(5)

0

=

1

2

β−5

α

5

N

(0)

x

+

5

N

(0)

x−5

5

L

x

5

L

x−5

5

L

0

F

x

. (12.2.3)

This corresponds to the calculation of n

1

(t+1) using an age-classified pop-

ulation projection matrix with fertility defined as in Section 3.3.1. There,

we used this same tactic of calculating the number of women exposed to

the risk of childbearing as the average of the numbers at the beginning and

at the end of the period. This is a slight overstatement of exposure if the

increase is at a steady rate, that is, rising geometrically and so concave up-

ward. The correction for this has been presented elsewhere (Keyfitz 1968,

p. 252) and will here be disregarded.

274 12. Projection and Forecasting

Extension to All Ages and Both Sexes. If convenience in arranging the

worksheets were thereby served, we could first confine the calculation to

ages under β, the end of reproduction. The survivorship and birth opera-

tions described above can be repeated for an indefinite sequence of 5-year

cycles in disregard of the population beyond reproduction. Older ages can

be filled in by repeated application of (12.2.1).

Males, like females beyond age β, can be dealt with after the projections

for the female ages under age β are completed. Pending parental control

of the sex of offspring, we can suppose a fixed ratio of males to females

among births. If this ratio is taken as s, ordinarily a number close to 1.05,

then multiplying the girl births by s, or the number of girls under 5 years

of age by s

5

L

∗

0

/

5

L

0

(where

5

L

∗

0

refers to the male life table,

5

L

0

to the

female), will give the corresponding number of boys. The male part of the

projection can then be filled out by repeated application of (12.2.1), using

a life table for males.

The procedure described to this point can alternatively be arranged as

matrix multiplication to secure a numerically identical result. The number

of females in successive age groups is recorded in the top half of a vertical

vector n and the number of males in the bottom half. The vector, containing

36 elements if 5-year age intervals to 85–89 are recognized for each sex, is

premultiplied by a matrix M whose nonzero elements are in its subdiagonal

and its first and nineteenth rows. Population after t cycles of projection at

constant rates will be n(t)=M

t

n(0). If fertility ends at age β = 50, the

upper left-hand corner of the matrix will be a 10×10 submatrix containing

birth elements in its first row, and constituting the self-acting portion of

the larger matrix (Table 12.2). Every part of the preceding description can

be readily altered to provide for different rates from one period to another,

and in practical work rates are assumed to change.

The upper left-hand 10 ×10 submatrix of M shown in Table 12.2 can be

called A and analyzed with the methods of Chapter 7. By drawing a graph,

we can show A to be irreducible in that its positive elements are so arranged

as to permit passage from any position to any other. Its primitivity—that

there is at least one power k such that all elements of A

k

are positive

for that k—follows as long as any two relatively prime ages have nonzero

fertility. Alternatively, the entire matrix M can be analyzed, as long as

the irreducible nature of the matrix is recognized, so that the appropriate

eigenvalues and eigenvectors are used to draw conclusions about future

population (Section 7.2.2).

This description corresponds to the usual execution of the projection in

being female dominant: all births are imputed to females. The same theory

is applicable to a process in which births are imputed to males. With the

prevailing method of reproduction a male and a female are required for each

birth, and with either male or female dominance the other sex is implicitly

taken to be present in whatever numbers are required. Two-sex models

in which neither sex is dominant are nonlinear, with reproductive rates