Kenny Anthony. Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

to say that the soul, or the mind, thinks. Aristotle had said, ‘It is better

not to say that the soul pities, or learns, or thinks, but that it is the human

being that does these things with his soul’ (De An. 408b15), and Aquinas

echoes this when he says, ‘It can be said that the soul thinks, just as the eye

sees, but it is better to say that the human being thinks with the soul.’ If we

take this comparison seriously, we must say that just as an eye, outside a

body, is not really an eye at all any more, so a soul, separated from a body,

is not really a soul any more.

Aquinas goes some way to accepting this, but he does not treat it as a

reductio ad absurdum. He agrees that a person’s disembodied so ul is not the

same thing as the person whose soul it is. St Paul wrote, ‘if in this life only

we have hope in Christ we are of all men most miserable’ (1 Cor. 15: 19).

St Thomas, in commenting on this passage, wrote: ‘A human being

naturally desires his own salvation; but the soul, since it is part of the

body of a human being, is not a whole human being, and my soul is not I;

so even if a soul gains salvation in another life, that is not I or any human

being.’ Whether or not Aquinas’ belief in the possibility of disembodied

souls is coherent, it is remarkable that he refuses to identify such a soul,

even if beatiWed, with any self or ego. He refuses to identify an individual

with an individual’s soul, as many theologians before him, and many

philosophers after him, were willing to do.

Scotus versus Aquinas

Duns Scotus’ philosophy of mind diVered profoundly from that of Aqui-

nas, in accordance with the diVerences in their metaphysical systems.

Aquinas believed that there was no purely intellectual knowledge of

individuals, because individuation was by matter, and intellectual thought

was free of matter. But for Scotu s there exists an individual element, or

haecceitas, which is an object of knowledge: it is not quite a form, but is

suYciently like a form to be present in the intellect. And because each

thing has within it a formal, intelligible, principle, the ground is cut

beneath the basis on which Aquinas rested the need for a species-speciWc

agent intellect in human beings.

Individuals, unlike universals, a re things that come into and go out of

existence. If the proper objects of the intellect include not only universals

MIND AND SOUL

242

but individual items like a haecce itas, then there is a possibility of such an

object being in the intellect without existing in reality. The possibility that

one and the same object might be in the intellect and not exist in reality

was the possibility that Aquinas’ intentionality theory was careful to avoid.

An individual form, for Scotus, may exist in the mind and yet the

corresponding individual not exist. Hence the individual form present in

the intellect can be only a representation of, and not identical with, the

object whose knowledge it embodies. Hence a window is opened at the

level of the highest intellectual knowledge, a window to permit the entry

of the epistemological problems that have been familiar to us since Des-

cartes.

The diVerences between Aquinas and Scotus, so far as concerns the

intellect, are not so much a matter of explicit rejection by Scotus of

positions taken up by Aquinas. It is rather that a consideration of the

Scotist position leads one to reXect on its incompatibility at a deep level

with the Thomist anthropology. But when we turn from the intellect to

the will, things are very diVeren t. Here Scotus is consciously rejecting the

tradition that precedes him; he is innovating in full self-awareness. He

regards Aquinas as having misrepresented the nature of human freedom

and the relation between the intellect and the will.

For Aquinas, the root of human freedom was the will’s dependence on

the practical reason. For Scotus, the will is autonomous and sovereign. He

puts the question whether anything other than the will eVectively causes

the act of willing in the will. He replies, nothing other than the will is the

total cause of volition. What is contingent must come from an undeter-

mined cause, which can only be the will itself, and he argues against the

position which he attributes to ‘an older doctor’ that the indetermination

of the will is the result of an indetermination on the part of the intellect.

You say: this indetermination is on the part of the intellect, in so representing the

object to the will, as it will be, or will not be. To the contrary: the intellect cannot

determine the will indiVerently to either of contradictories (for instance, this will

be or will not be), except by demonstrating one, and constructing a paralogism or

sophistical syllogism regarding the other, so that in drawing the conclusion it is

deceived. Therefore, if that contingency by which this can be or not be was from

the intellect, dictating in this way by means of opposite conclusions, then nothing

would happen contingently by the will of God, or by God, because he does not

construct paralogism, nor is he deceived. But this is false. (Oxon. 2. 25)

MIND AND SOUL

243

Scotus’ criticism of the idea that the indeterminism of the will arises

from an indeterminism in the intellect is based on a misunderstanding of

the theory that he is attacking. The intellect in dictating to the reason does

not say ‘This will be’ or ‘This will not be’, but rather ‘This is to be’ or ‘This is

not to be’, ‘This is good’ or ‘This is not good’. If what is in question is a non-

necessary means to a chosen goal, it is possible for the intellect, without

error, to dictate both that something is good and that its opposite is good.

Moreover, in making the will the cause of its own freedom, Scotus’ theory

runs the danger of leading to an inWnite regress of free choices, where the

freedom of a choice depends on a previous free choice, whose freedom

depends on a previous one, and so on for ever.

Scotus was not unaware of this danger, and in opposition to the position

he attacks, he develops his own elaborate analysis of the structure of

human freedom, in a way that he believes holds out the possibility of

avoiding the regress. In any case of free action, he says, there must be some

kind of power to opposit es. One such power is obvious: it is the will’s power

to will after not willing, or its power to enact a succession of opposite acts.

Of course, the will can have no power to will and not will at the same

time—that would be nonsense—but while A is willing X at time t, A has

the power to not will X at time t þ 1.

But beside this obvious power, Scotus maintains, there is another, non-

obvious power, which is not a matter of temporal succession (alia, non ita

manifesta, absque omni successione). He illustrates this kind of power by imagining

a case in which a created will existed only for a single moment. In that

moment it could only have a single volition, but even that volition would

not be necessary, but would be free. Now while the lack of succession

involved in freedom is plainest in the case of the imagined momentary will,

it is there in every case of free action. That is, that while A is willing X at t,

not only does A have the power to not will X at t þ 1, but A also has the

power to not will X at t, at that very moment. The power, of course, is not

exercised, but it is there all the same. It is quite distinct from mere logical

possibility—the fact that there would be no contradiction in A’s not

willing X at this very moment—it is something over and above: a real

active power. It is this power that, for Scotus, is the heart of human

freedom.12

12 See the discussion of synchronic contingency in Ch. 6 above.

MIND AND SOUL

244

In defending the coherence of the concept of this non-manifest power,

Scotus makes use of a logical distinction that can be traced back to Abelard.

Consider the sentence ‘This will, which is willing X at t, can not will X at t’.

It can be taken in two ways. Taken one way (‘in a composite sense’) it

means that ‘This will, which is willing X at t, is not willing X at t’ is possibly

true. Taken in that way the sentence is false, and indeed necessarily false.

Taken in another way (‘in a divided sense’) it means that it is possible that

not-willing X at time t might have inhered in this will which is actually willing

X at time t . Taken in this sense, Scotus maintains, the sentence can well be

true (Ord. 4. 417–18).

Ockham versus Scotus

Ockham rejected the non-manifest power that Scotus had introduced. It was

not a genuine power, he said, because it was totally incapable of actualizati on

without contradiction. The power not to sit at time t should be regarded as a

power existing not at t (when I am actually sitting) but at time t 1, the last

moment at which it was still open to me to be standing up at t.

Like Ockham, I Wnd Scotus’ occult powers incomprehensible. But Ock-

ham’s rejection of them is not suYciently wholehearted. Scotus’ mistake

was to regard a power as being a datable event just like the exercise of a

power. Ockham accepts the notion of a power for an instant, and simply

antedates the temporal locati on of the power. But having a power is a state;

it is not a momentary episode like an action.

It may be true, at t, that I have the power to do X, without that entailing

that I have the power to do-X-at-t. Of course, it may be true that I can do X

at t, but in order to analyse such a statement we must distinguish between

power and opportunity. For it to be true that I can swim now it is necessary

not only that I should now have the power to swim (i.e. know how to swim)

but also have the opportunity to swim (e.g. that there should be a suY cient

amount of water about). Scotus and Ockham fail to make the appropriate

distinction, and their temporarily qualiWed powers are an amalgam of the

two notions of power and opportunity. But an opportunity is not an occult

power of mine: it is a matter of the states and powers of other things, and the

compossibility of those states and powers with the exercise of my power.13

13 See my Will, Freedom and Power, ch. 8.

MIND AND SOUL

245

In spite of their disagreements about the precise nature of freedom,

Ockham is at one with Scotus in stressing the autonomy of the will. The

will’s action is not determined either by a natural desire for happiness, nor

by any command of the intellect, nor by any habit in the sensitive appetite:

it always remains free to choose between opposites.

On the cognitive side of the soul, Ockham regularly writes as if he

recognizes the three sets of powers traditional in Aristotelian philosophy:

outer sense (the familiar Wve senses), inner sense (the imagination), and

intellect. However, when he discusses the intellect it is not at all clear that

he is talking about the same facu lty that Aristotle and Aquinas described.

For Aquinas, the intellect was distinguished from the senses because its

object was universal while theirs was particular; and the individual was

directly knowable only by the senses. But for Ockham, both particular and

universal can be known directly by both senses and intellect.

For Aquinas, a human mind’s knowledge of a particular horse would be

subsequent to the acquisition of the universal idea (species) of horse, formed

out of sense-experience by the creative activity of a faculty peculiar to

human beings, the agent intellect. Once this idea has been acquired, it can

be applied to individuals only by a reXective activity of the intellect,

reverting to sensory experience. Ockham regards all this apparatus as

superXuous.

We can suppose that the intellect can be brought to the knowledge of an

individual by the same process as it is led to the knowledge of a universal. If it is

brought to knowledge of the universal by the agent intellect on its own, then the

agent intellect on its own—we may suppose—can equally easily bring it to the

knowledge of an individual. And as it can be directed by the intelligible species or

by the phantasm to think of one universal rather than another, so too we can

suppose that it can be directed by the intelligible species to think of this individual

and not another. In whatever way after the acquisition of the universal concept

the mind can be directed to think of one individual rather than another (even

though the knowledge of the universal concerns all individuals equally) in just the

same way it can be directed, even before the acquisition of the universal, to think

of this individual rather than another. (OTh. 1. 493)

When Ockham claims that the intellect can know the individual, he is

not basing his claim on the existence of a formal element of individuation,

like the Scotist haecceitas. He rejected any such principle and denied the need

for it. Whatever exists in the real world just is individual, and needs no

MIND AND SOUL

246

principle to individuate it. His point in the quoted passage is that whatever

philosophical account you give of the acquisition and employment of

knowledge of the universal, exactly the same acc ount can be given of the

acquisition and employment of knowledge of the individual. If that is so,

then it seems a violation of Ockham’s razor to postulate two diVerent

faculties with exactly the same function.

In fact Ockham does distinguish between the senses and the intellect,

but whenever he describes the operation of the intellect, it seems to be a

mere double of either the inner or the outer sense. The very same object

that we sense is intuitively grasped by the intellect under exactly the same

description; the intellect’s grasp of the object sensed is parallel to the

imagination’s representation of the object senses (OTh. 1. 494). Seeing a

white object, imagining a white object, and thinking of a white object are,

for Ockham, mental operations of a similar kind. The one feature which

seems to be peculiar to the intellect is the act of judging that there is a

white object. This judgement is an act not of the senses, nor of the will, but

of the intellect alone (OTh. 6. 85–6).

Just as he was uncon vinced by the traditional arguments for God’s

existence, so Ockham was unconvinced by the arguments of medieval

Aristotelians to prove the immortality of the soul. If a soul is an immaterial

and incorruptible form, he said,

it cannot be known evidently either by argument or by experience that there is

any such form in us. Nor can it be known that thinking in us belongs to such a

substance, nor that such a soul is a form of the body. I do not care what Aristotle

thought of this, because he always seems to speak hesitantly. But these three

things are simply objects of faith. (OTh. 9. 63–4)

Pomponazzi on the Soul

As the Middle Ages drew to an end, this scepticism about philosophical

proofs of immortality became more widespread. The arguments for and

against the immortality of individual human beings are set out in Pietro

Pomponazzi’s pamphlet of 1516, On the Immortality of the Soul. Pomponazzi

begins by considering the opinion that there is a single, immortal, intellec-

tual human soul, while e ach individual human being has only a mortal

MIND AND SOUL

247

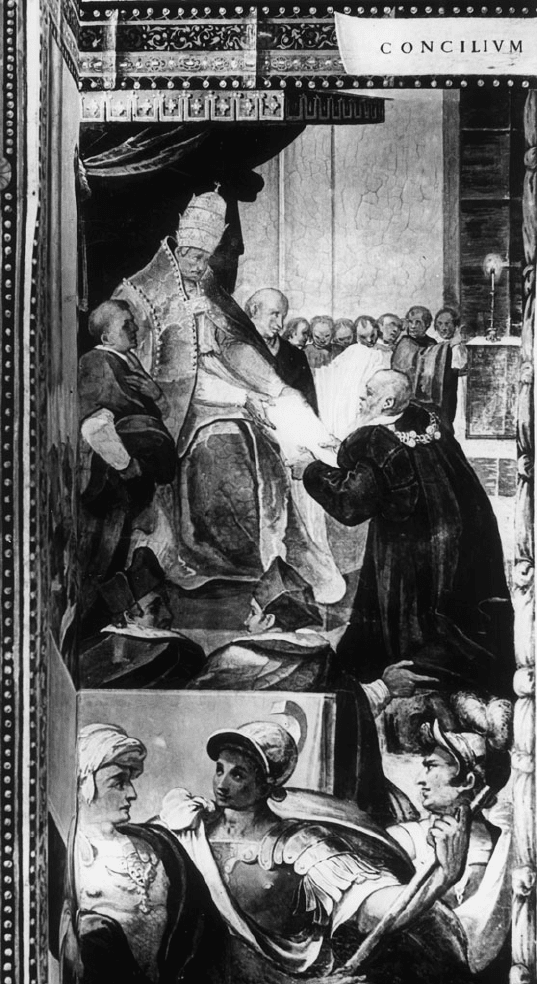

A representation, from the Sala Sistina in the Vatican library, of the Wfth Lateran

Council, which condemned Pomponazzi’s teaching on the immortality of the soul.

MIND AND SOUL

248

soul. This opinion, which he attributes to Averroes and Themistius, is, he

tells us, ‘widely held in our time and by almost all is conWdently taken to be

that of Aristotle’. In fact, he says, it is false, unintelligible, monstrous, and

quite foreign to Aristotle.

To show that the opinion is false, Pomponazzi refers the reader to

arguments used by St Thomas Aquinas in his De Unitate Intellectus.To

show that it is un- Aristotelian he appeals to the teaching of the De Anima

that, in order to operate, the intellect always needs a phantasm, which is

something material. Our intellectual soul is an act of a physical and organic

body. There may be types of intelligence that do not need an organ to

operate, but the human intellect is not one of them.

A body, however, can function as a subject or obje ct. Our senses need

bodies in both ways: their organs are bodily and their objects are bodily.

The intellect, however, does not need a body as subject, and it can perform

operations (such as reXecting upon itself) which no bodily organ can do:

the mind can think of itself, while the eye cannot see itself. But this does

not mean that the intellect can operate entirely independently from the

body.

Aquinas is again invoked in order to refute another opinion, the Platonic

view that while every human has an individual immortal soul, this soul is

related to his body only as mover to moved—like an ox to a plough, say.

Like Aquinas, Pomponazzi appeals to experience:

I who am writing these words am beset with many bodily pains, which are the

function of the sensitive soul; and the same I who am tortured run over their

medical causes in order to remove these pains, which cannot be done save by the

intellect. But if the essence by which I feel were diVerent from that by which

I think, how could it possibly be that I who feel am the same as I who think? (c. 6,

p. 29814)

We must conclude that the intellectual soul and the sensitive soul are one

and the same in man.

In this, Pomponazzi is in agreement with St Thomas: but at this point he

parts company with him. Thomas, he said, believed that this single soul was

properly immortal, and only mortal in a manner of speaking (secundum quid).

But he, Pomponazzi, will now set out to show that the soul is properly

14 In E. Cassirer et al. (eds.), The Renaissance Philosophy of Man (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1959).

MIND AND SOUL

249

mortal, and only immortal in a manner of speaking. He continues to speak

of Aquinas with great respect. ‘As the authority of so learned a Doctor is

very great with me, not only in divinity but also in interpretation of

Aristotle, I would not dare to aYrm anything against him: I only advance

what I say in the way of doubt’ (c. 8, p. 302).

By nature man’s being is more sensuous than intellective, more mortal

than immortal. W e have more vegetative and sensory powers than intel-

lectual powers, and many more people devote themselves to the exercise of

those powers than to the cultivation of the intellect. The great majority of

men are irrational rather than rational animals. More seriously, the soul

can only be separable if it has an operation independent of the body. But

both Aristotle and Aquinas maintain that the phantasm is essential for any

exercise of thought: hence the soul needs the body, as object if not as

subject. Souls can only be individuated by the matter of the bodies they

inform: it will not do to say that souls, separate from their bodies, are

individuated by an abiding aptitude for informing a particular body.

Did Aristotle believe in immortality? In the Ethics he seems to assert that

there is no happiness after death, and when he says that it is possible to

wish for the impossible, the example he gives of such a wish is the wish for

immortality. St Thomas asks why, if Aristotle thought there was no

survival of death, he should want people to die rather than to live in evil

ways. But the only immortal intelligence Aristotle seems to accept is one

that precedes, as well as survives, the death of the individual human.

However, Pomponazzi says, he has no desire to seek a quarrel with

Aristotle: what is a Xea against an elephant? (c. 8, p. 313; c. 10, p. 334).

The Aristotelian conclusion which Pomponazzi Wnally accepts is this:

the human soul is both intellective and sensitive, and strictly speaking it is

mortal, and immortal only secundum quid. In all its operations the human

intellect is the actuality of an organic body, and always depends on the

body as its object. The human soul is what makes a human individual, but

it is not itself a sub sistent individual (c. 9, p. 321). This position ‘agrees with

reason and experience, it maintains nothing mythical, nothing dependent

on Faith’. The intellect that, according to Aristotle, survives death is no

human intellect. When we call the soul immortal it is only like calling grey

‘white’ when it is compared to a black background.

The immortality of the soul, Pomponazzi concludes, is an issue like

the eternity of the world. Philosophy cannot settle either way whether

MIND AND SOUL

250

the world ever had a beginning; it is equally impotent to settle whether the

soul will ever have an end. His last word—sincere or not—is this. We must

assert beyond doubt that the soul is immortal: but this is an act of faith, not

a philosophical conclusion .

MIND AND SOUL

251