Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

oxford philosophers

164

IX

OXFORD PHILOSOPHERS

The Fourteenth-Century University

Among those who were critical of Aquinas after his death were a number of

Franciscans associated with Oxford. During the thirteenth century, the University

of Paris had undoubtedly dominated the learned world. By the end of the cen-

tury, Paris and Oxford were almost like two campuses of a single university, with

many masters passing between the two institutions. But by 1320 Oxford had

established itself as a firmly independent centre, and indeed had taken over from

Paris the hegemony of European scholasticism. Paris continued to produce dis-

tinguished scholars: Jean Buridan, for instance, Rector of the University in 1340,

who reintroduced Philoponus’ theory of impetus, and Nicole Oresme, Master of

the College of Navarre in 1356, who translated much of Aristotle into French

and who explored, without endorsing, the hypothesis that the earth rotated daily

on its axis. But the fourteenth-century thinkers who made most mark on the

history of philosophy were all Oxford associates.

There were two striking, and at first sight contradictory, features of the fourteenth-

century university as typified in Oxford. These were the extreme length of the

curriculum, and the remarkable youthfulness of the institution. The curriculum in

Arts lasted eight or nine years, with a BA in the fifth year, and an MA after the

seventh. Equipped with an MA or its equivalent a typical theology student then

spent four years attending lectures on the Bible and the Sentences; three years

later he himself began to lecture, first on the Sentences (as a bachelor), then on

the Bible (as a ‘formed bachelor’). Eleven years or so after starting his theological

studies he became a regent master in theology, and continued for at least another

two years lecturing on the Bible and supervising students before his course was

complete. A university course of studies could last from one’s fourteenth to one’s

thirty-sixth year.

Such a long period of training might be expected to produce a gerontocracy;

yet hardly anyone in the university of the period was over forty. This was because

there was not the sharp division familiar in modern universities between students

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM164

oxford philosophers

165

and faculty. Lecturing and supervision were carried out by students themselves at

specified periods of their studies. Someone like Aquinas who continued teaching

and writing nearly to his death at the age of fifty would have been most unusual

in fourteenth-century Oxford.

Relationships between the faculties of Arts and of theology were not always

easy, and in the last years of the thirteenth century Oxford, like Paris, had been

affected by a backlash of Augustinian theologians against Aristotelian philosophers.

In the words of Etienne Gilson, ‘After a short honeymoon, theology and philo-

sophy thought they had discovered that their marriage had been a mistake.’ The

theologians’ principal targets were scholars who interpreted Aristotle in the style

of Averroes; but they attacked also some of the philosophical teachings of Aquinas,

despite the hostility he had himself shown to Averroes’ teachings.

In 1277 the congregation of Oxford University formally condemned thirty

theses in grammar, logic, and natural philosophy. Several of the theses which

were condemned were corollaries of Aquinas’ teaching that in each human being

there was only a single form, namely, the intellectual soul. Congregation con-

demned, for instance, the view that when the intellectual soul entered the embryo,

the sensitive and vegetative souls ceased to exist. The issue was of concern to

theologians, not just philosophers, because Aquinas’ view was taken to imply that

the body of Jesus in the tomb, between his death and resurrection, had nothing

in common, save bare matter, with his living body. Victory in a long-running

controversy was now given to those who, like St Bonaventure, believed in a

plurality of forms in an individual human being. Supporters of St Thomas tried to

appeal to Rome, but came to grief.

The Oxford congregation which condemned the thesis of the single form was

presided over by an Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Kilwardby, who was, like

St Thomas, a Dominican. When, shortly afterwards, Kilwardby was summoned to

Rome as a Cardinal, he was succeeded as Archbishop by an Oxford Franciscan,

John Peckham. Peckham persecuted with even greater vigour those who sup-

ported Aquinas on this issue. For some time to come Oxford was dominated by

Franciscan thinkers who, though very well acquainted with Aristotle, in this and

other matters rejected Aquinas’ distinctive version of Aristotelianism.

Duns Scotus

The most distinguished of these was John Duns Scotus. He was born about 1266

perhaps at Duns, near Berwick-on-Tweed. He studied at Oxford between 1288

and 1301, and was ordained priest in 1291. Merton College used to claim him

as a fellow, but the claim is now generally regarded as baseless. While at Oxford

he lectured on the Sentences, and he gave similar courses in Paris in 1302–3, and

possibly also at Cambridge a year later. In the last year of his short life he lectured

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM165

oxford philosophers

166

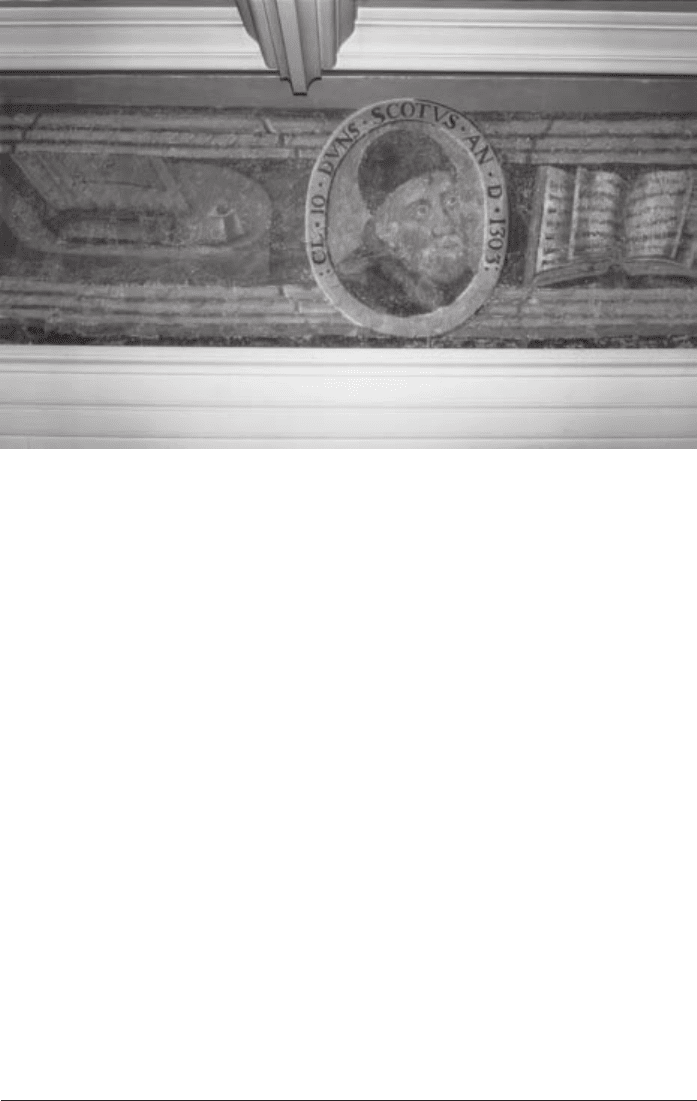

Figure 19 Roundel of Duns Scotus in the Bodleian Library frieze, Oxford.

(Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

in Cologne, where he died in 1308. His lecture courses survived in an incomplete

and chaotic state, in the form both of his own corrected autographs and of the

notes of his pupils. A definitive edition of his works still awaits completion. His

language is crabbed, technical, and unaccommodating; but through its thickets it

has always been possible to discern an intellect of unusual sophistication. Scotus

well deserved his sobriquet ‘The subtle doctor’.

On almost every major point of contention Scotus took the opposite side to

Aquinas. In his own mind, if not in the light of history, equal importance attached

to his disagreements with another of his seniors, Henry of Ghent, an independent

Parisian master of the 1280s who occupied a middle position between the

Augustinians and the extreme Aristotelians. Scotus was always anxious to situate

his own positions in relation to Henry’s stance, and it was through Henry’s eyes

that he saw many of his predecessors.

Aristotle had defined metaphysics as the science which studies Being qua being.

Scotus makes great use of this definition, broadening its scope immeasurably by

including within Being the infinite Christian God. According to Scotus for some-

thing to be is for it to have some predicate, positive or negative, true of it. Any-

thing, whether substance or accident, belonging to any of Aristotle’s categories

has being, and is part of Being. But Being is much greater than this, for whatever

falls under Aristotle’s categories is finite, and Being contains the infinite. If we

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM166

oxford philosophers

167

wish to carve up Being into its constituent parts, the very first division we must

make is between the finite and the infinite.

Aquinas too had talked of Being, but he understood it in a different way. Each

kind of thing had its own kind of being: for a living thing, for instance, to be was

the same as to be alive; and so among living things there were as many different

types of being as there were different types of life. This did not imply that the

verb ‘to be’ had a different meaning when it was applied to different kinds of

thing. When we say that robins are birds and herrings are fish, we are not making

a pun with the word ‘are’. The verb ‘to be’, in Aquinas’ terms, was neither

equivocal, like a pun, nor univocal, like a straightforward predicate such as ‘yel-

low’; it was analogous. In this it resembled a word like ‘good’. We can speak of

good strawberries and good knives without punning on ‘good’, even though the

qualities that make a strawberry good are quite different from those that make a

knife good. Similarly we can speak, without equivocation, of the being of many

different kinds of thing, even though what their being consists of differs from

case to case.

Scotus disagreed with Aquinas here. For him ‘being’ was not analogous, but

univocal: it had exactly the same meaning no matter what it was applied to.

It meant the same whether it was applied to God or to a flea. It was, in fact,

a disjunctive predicate. If you listed all possible predicates from A to Z, then the

verb ‘to be’ was equivalent to ‘to be A or B or C . . . or Z’. The meaning of ‘to

be’, therefore, depended on the content of all the predicates; it did not in any

way depend on the subject of the sentence in which it occurred. A predicate must

be univocal, Scotus argued, if one is to be able to apply to it the principle of non-

contradiction, and make use of it in deductive arguments.

Being, for Scotus, includes the Infinite. How does he know? How can he

establish that, among the things that there are, is an infinite God? He offers a

number of proofs, which at first sight resemble those of Aquinas. One proof, for

instance, makes use of the concept of causality to prove the existence of a First

Cause. Suppose that we have something capable of being brought into existence.

What could bring it into existence? It must be something, because nothing can-

not cause anything. It must be something other than itself, for nothing can cause

itself. Let us call that something else A. Is A itself caused? If not, it is a First Cause.

If it is, let its cause be B. We can repeat the same argument with B. Then either

we go on for ever, which is impossible, or we reach an absolute First Cause.

It might be thought that Scotus could say, at this point, ‘and that is what all

men call God’. But no: unlike Aquinas, who took as his starting point the actual

existence of causal sequences in the world, Scotus began simply with the possibil-

ity of causation. So the argument up to this point has proved only the possibility

of a first cause: we still need to prove that it actually exists. Scotus in fact goes

one better and proves that it must exist. The proof is quite short. A first cause,

by definition, cannot be brought into existence by anything else; so either it just

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM167

oxford philosophers

168

exists or it does not. If it does not exist, why not? There is nothing that could

cause its non-existence, if that existence is possible at all. But we have shown that

it is possible; therefore it must exist. Moreover, it must be infinite; because there

cannot be anything that could limit its power. If there were any incoherence in the

notion of infinite being, Scotus says, it would long ago have been detected – the

ear quickly detects a discord, the intellect even more easily detects incompatibilities.

Scotus prefers his kind of proof to Aquinas’ Five Ways because it begins not

with contingent facts of nature, but with purely abstract possibilities. If you start

from mere physics, he believed, you will never get beyond the finite cosmos; and

in any case you may have got your physics wrong (as Aquinas, as it happens, had).

The infinite God, reflecting on his own essence, sees it as capable of being

reproduced or imitated in various possible partial ways: it is this which, before all

creation, produces the essences of things. These essences, as Scotus conceives

them, are in themselves neither single nor multiple, neither universal nor particu-

lar. They resemble – and not by accident – Avicenna’s horseness, which was not

identical either with any of the many individual horses, nor with the universal

concept of horse in the mind. By a sovereign and unaccountable act of will, God

decrees that some of these essences should be instantiated; and thus the world is

created.

Creatures in the world, for Scotus as for other scholastics, are differentiated

from each other by the different forms they possess. Socrates possesses the form

of humanity; a different form is possessed by Brownie the donkey (a favourite

example of Franciscan philosophers). But at this point Scotus introduces a new

kind of form, or quasi-form. According to Aquinas, two humans, Peter and Paul,

were distinct from each other not on account of their form, but on account of

their matter. Scotus rejected this, and postulated a distinct formal element for

each individual: his haecceitas or thisness. Peter had a different haecceitas from

Paul, and so, presumably, did Brownie from Eeyore.

In an individual such as Socrates we have, then, according to Scotus, both a

common human nature and an individuating principle. The human nature is a

real thing which is common to both Socrates and Plato; if it were not real,

Socrates would not be any more like Plato than he is like a line scratched on a

blackboard. Equally, the individuating principle must be a real thing, otherwise

Socrates and Plato would be identical. The nature and the individuating principle

must be united to each other, and neither can exist in reality apart from the

other: we cannot encounter in the world a human nature that is not anyone’s

nature, nor can we meet an individual that is not an individual of some kind

or other. Yet we cannot identify the nature with the haecceitas: if the nature

of donkey were identical with Brownie’s thisness, then every donkey would be

Brownie.

Is the nature really distinct from the haecceitas or not? We seem to have reached

an impasse: there are strong arguments on both sides. To solve the problem,

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM168

oxford philosophers

169

Scotus made use of a new concept, which rapidly became famous: the objective

formal distinction (distinctio formalis a parte rei). The nature and the haecceity

are not really distinct, in the way in which Socrates and Plato are distinct, or in

the way in which my two hands are distinct. Nor are they merely distinct in

thought, as Socrates and the teacher of Plato are. Prior to any thought about

them, they are, he says, formally distinct: they are two distinct formalities in one

and the same thing. It is not clear to me, as it was not clear to many of Scotus’

successors, how the introduction of this terminology clarifies the problem it

was meant to solve. Scotus applied it not only in this context but also widely

elsewhere, for instance to the relationship between the different attributes of the

one God, and to the relationship between the vegetative, sensitive, and rational

souls in humans.

The introduction of the notion of haecceity affects Scotus’ conception of the

human intellect. Aquinas had denied the possibility of purely intellectual know-

ledge of individuals, because the intellect could not grasp matter as such, and

matter was the principle of individuation. But the haecceitas though not a form

is quite distinct from matter, and is sufficiently like a form to be present in the

intellect. According to Scotus, because each thing has within it an intelligible

principle, the human intellect can grasp the individual in its singularity.

Scotus extended the scope of the intellect also in a different direction. Aquinas

maintained that in the present life the intellect was most at home in acquiring, by

abstraction from experience, knowledge of the nature of material things. Scotus

said that to define the proper object of the intellect in this way was like defining

the object of sight as what could be seen by candlelight. The saints in heaven

enjoyed the intellectual vision of God; if we were to take the future life as well as

the present into account we must say that the proper object of the intellect was as

wide as Being itself. Scotus did not deny that in fact all our knowledge arises from

experience, but he thought that the dependence of the intellect on the senses in

the present life was perhaps a punishment for sin.

Scotus makes a distinction between intuitive and abstractive knowledge.

Abstractive knowledge is knowledge of the essence of an object, considered in

abstraction from the question whether the object exists or not. Intuitive know-

ledge is knowledge of an object as existent: it comes in two kinds, perfect in-

tuition when an object is present, and imperfect intuition which is memory of a

past or anticipation of a future object.

On the relationship between the intellect and the will, Scotus once more

departs from the position of St Thomas in several ways. Historians of philosophy

call him a ‘voluntarist’, a partisan of the will against the intellect. What does this

mean precisely? Scotus asks whether anything other than the will effectively causes

the act of willing in the will. He replies, nothing other than the will is the total

cause of its volition. Aquinas had maintained that the freedom of the will derived

from an indeterminacy in practical reasoning. The reason could decide that more

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM169

oxford philosophers

170

than one alternative was an equally good means to a good end, thus leaving the

will free to choose. Scotus maintained that any such contingency must come from

an undetermined cause which can only be the will itself. But in making the will

the cause of its own freedom, Scotus’ theory runs the danger of leading to an

infinite regress of free choices, where the freedom of a choice depends on a pre-

vious free choice whose freedom depends on a previous one, and so on for ever.

This was not a danger of which Scotus was unaware, and in the course of his

discussion of God’s foreknowledge of free actions he introduced a new kind of

potentiality, uniquely characteristic of human free choice, which holds out the

possibility of avoiding the regress.

When we have a case of free action, Scotus says, this freedom is accompanied

by an obvious power to do opposite things. True, the will can have no power to

will X and not-will X at the same time – that would be nonsense – but there is

in the will a power to will after not willing, or to a succession of opposite acts.

That is to say that while A is willing X at time t, A can not-will X at time t+1.

This, he says, is an obvious power to do a different kind of act at a later time.

But, Scotus says, there is another non-obvious power, which is without any

temporal succession. He illustrates this kind of power by imagining a case in

which a created will existed only for a single instant. In that instant it could only

have a single volition, but even that volition would not be necessary, but be free.

The lack of succession involved in this kind of freedom is most obvious in the

case of the imagined momentary will, but it is in fact there all the time. That is to

say, that while A is willing X at t, not only does A have the power to not-will X

at t+1, but A also has the power to not-will X at t, at that very moment. This is

an explicit innovation, the postulation of a non-manifest, we might even say occult,

power.

Scotus carefully distinguishes this power from logical possibility; it is something

which accompanies logical possibility but is not identical with it. It is not simply

the fact that there would be no contradiction in A’s not willing X at this very

moment, it is something over and above – a real active power – and it is the heart

of human freedom.

The sentence ‘This will, which is willing X, can not-will X’ can be taken in two

ways. Taken one way (‘in a composite sense’) it means that ‘This will, which is

willing X, is not-willing X’ is possibly true; and that is false. Taken another way

(‘in a divided sense’), as meaning that this will which is now willing X at t has the

power of not-willing X at t+1, it is obviously true.

But what of ‘This will, which is willing X at t, can not-will X at t’? Here too,

in accordance with Scotus’ innovation, we can distinguish between the com-

posite sense and the divided sense. It is not the case that it is possible that this

will is simultaneously willing X at t and not-willing X at t. But it is true that it is

possible that not-willing X at time t might inhere in this will which is actually

willing X at time t.

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM170

oxford philosophers

171

Scotus at this point makes a distinction between instants of time and instants

of nature: there can be more than one instant of nature at the same instant of

time. We here encounter, for the first time in philosophy, what later logicians

were to call ‘possible worlds’. At the same instant of time, on this account, there

may be several simultaneous possibilities. These synchronic possibilities need not

be compatible with each other, as in the case in point: they are possible in

different possible worlds, not in the same possible world.

For better or worse, the notion of possible worlds was to have a distinguished

future in the history of philosophy. Scotus’ account of the origin of the world,

described earlier, makes God’s creation a matter of choosing to actualize one

among an infinite number of possible universes. Later philosophers were to sep-

arate the notion of possible worlds from the notion of creation, and to take the

word ‘world’ in a more abstract way, so that any totality of compossible situations

constitutes a possible world. This abstract notion was then used as a means of

explaining every kind of power and possibility. Credit for the introduction of the

notion is usually given to Leibniz, but it belongs instead to Scotus. It has proved

the longest-lived of the subtleties which gave him his nickname.

Despite his uncommon ingenuity as a philosopher, Scotus in his writings

systematically restricts the scope of philosophy. Aquinas had made a distinction

between truths about God graspable only by faith, such as the Trinity, and other

truths knowable by reason; and he had included in the latter class knowledge of

all the principal attributes of God, such as omnipotence, immensity, omnipres-

ence, and so on. Scotus, on the contrary, thought reason impotent to prove that

God was omnipotent or just or merciful. A Christian knows, he argued, that

omnipotence includes the power to beget a Son; but this is not something which

pure reason can prove that God possesses. In a similar way many topics which, for

Aquinas, fell within the province of philosophy are by Scotus kicked upstairs for

treatment by the theologian.

In theology itself, Scotus was best known for his sponsorship of belief in

the immaculate conception. This doctrine is not, as is often thought, the belief

that Mary conceived Jesus as a virgin; it is the belief that Mary, when herself

conceived, was free from the inherited taint of original sin. (The many people

nowadays who disbelieve in original sin automatically believe in the immaculate

conception of Mary.) The doctrine is important in the history of philosophy

because it relates to a long-standing philosophical dispute. Aquinas had denied

that Mary was conceived immaculate because, following Aristotle, he did not

believe that a newly conceived foetus had an intellectual soul during its first few

weeks of existence. Scotus believed that the soul entered the body at the moment

of conception, and the eventual acceptance by the Church of the doctrine of the

immaculate conception was a victory for his thesis. This philosophical disagree-

ment is obviously relevant to the attitude taken by Catholics in the present day on

the issue of abortion.

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM171

oxford philosophers

172

Gerard Manley Hopkins, the most famous Scotist of modern times, singled out

for special praise his championing of the immaculate conception. Ranking Scotus

among the greatest of all philosophers, he describes him as:

Of realty the rarest-veined unraveller; a not

Rivalled insight, be rival Italy or Greece;

Who fired France for Mary without spot.

Ockham’s Logic of Language

Scotus’ tendency to restrict the field of operation of philosophy is carried further

by his successor, William Ockham. William, like Scotus a Franciscan friar, came

from the village of Ockham in Surrey; he was born about 1285 and studied at

Oxford shortly after Scotus had left it. He lectured on the Sentences from 1317 to

1319, but never took his MA, having fallen foul of the Chancellor of the Univer-

sity, John Lutterell. He went to London where, in the 1320s, he wrote up his

Oxford lectures, and composed a systematic treatise on logic as well as comment-

aries on Aristotle and Porphyry. In 1324 he was summoned to Avignon to answer

charges of heresy brought by Lutterell, and soon afterwards gave up his interest

in theoretical philosophy.

Many of Ockham’s positions in logic and metaphysics were taken up either in

development of, or in opposition to, Duns Scotus. Though his thought is less

sophisticated than that of Scotus, his language is mercifully much clearer. Like

Scotus, Ockham regards ‘being’ as a univocal term, applicable to God in the same

sense as to creatures. He allows into his system, however, a much less extensive

variety of created beings, reducing the ten Aristotelian categories to two, namely

substances and qualities. Like Scotus, Ockham accepts a distinction between

abstractive and intuitive knowledge; it is only by intuitive knowledge that we can

know whether a contingent fact obtains or not. Ockham goes beyond Scotus,

however, in allowing that God, by his almighty power, can make us have intuitive

knowledge of an object that does not exist. Whatever God can do through

secondary causes, he argues, God can do directly; so if God can make me know

that a wall is white by causing the white wall to meet my eye, he can make me

have the same belief without there being any white wall there at all. This thesis

obviously opens a road to scepticism, quickly traversed by some of Ockham’s

followers.

Ockham’s most significant disagreement with Scotus concerned the nature of

universals. He rejected outright the idea that there was a common nature existing

in the many individuals we call by a common name. No universal exists outside

the mind; everything in the world is singular. Ockham offered many arguments

against common natures, of which one of the most vivid is the following:

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM172

oxford philosophers

173

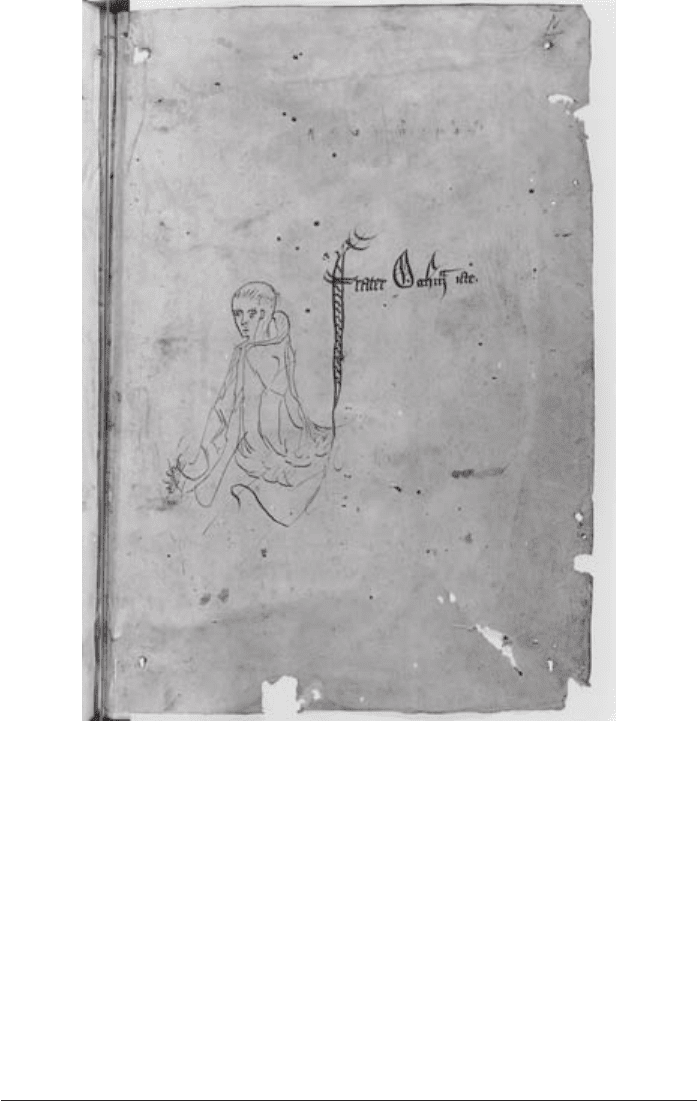

Figure 20 A doodle of William Ockham on the flysheet of a contemporary manuscript.

(By permission of the Master & Fellows of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge)

It follows from that opinion that part of Christ’s essence would be wretched and

damned; because that same common nature really existing in Christ really exists in

Judas and is damned.

Universals are not things but signs, single signs representing many things. There are

natural signs and conventional signs: natural signs are the thoughts in our minds,

and conventional signs are the words which we coin to express these thoughts.

Ockham’s view of universals is often called nominalism; but in his system it is

not only names, but concepts, which are universal. However, the title has a

certain aptness, since Ockham thought of the concepts in our minds as forming a

language system, a language common to all humans and prior to all the different

AIBC09 22/03/2006, 11:02 AM173