Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

early medieval philosophy

134

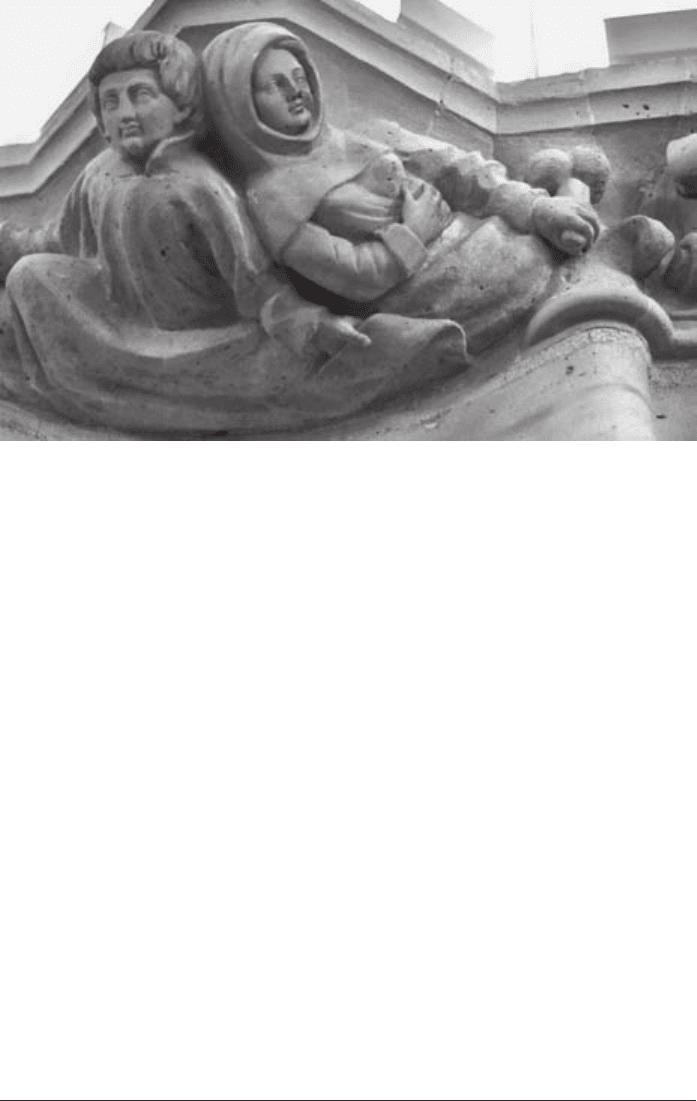

Figure 17 This sculpture on the walls of a famous prison shows Abelard

with Héloïse clutching his severed member.

(Conciergerie, Paris; photo: J. Burge)

1113 he was William’s successor at Notre Dame. While teaching there he took

lodgings with Fulbert, a canon of the Cathedral, and became tutor to his niece

Héloïse. He became her lover probably in 1116, and when she became pregnant

married her secretly. Héloïse had been reluctant to marry, and shortly after the

wedding retired to live in a convent. Fulbert, outraged by Abelard’s treatment

of his niece, sent two henchmen to his room at night to castrate him. Abelard

became a monk in the abbey of St Denis, near Paris, while Héloïse took the veil

as a nun at Argenteuil. Our knowledge of Abelard’s life up to this point depends

heavily upon a long autobiographical letter which he wrote to Héloïse some years

later, History of my Calamities. It is the most lively exercise in autobiography

since Augustine’s Confessions.

From St Denis, Abelard continued to teach (partly in order to support Héloïse).

He began to write theology, but his first work, the Theology of the Highest Good,

was condemned by a synod at Soissons in 1121 as unsound about the Trinity.

After a brief imprisonment Abelard was sent back to St Denis, but made himself

unpopular there and had to leave Paris. From 1125 to 1132 he was abbot of

St Gildas, a corrupt and boisterous abbey in a remote part of Brittany. He was

miserable there, and his attempts at reform were met with threats of murder.

Héloïse meanwhile had become prioress of Argenteuil, but she and her nuns were

made homeless in 1129. Abelard was able to found and support a new convent

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM134

early medieval philosophy

135

for them, the Paraclete, in Champagne. By 1136 he was back in Paris, lecturing

once more on Mont Ste Geneviève. His teaching attracted the critical attention of

St Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux and second founder of the Cistercian order, the

preacher of the Second Crusade. St Bernard denounced Abelard’s teaching to the

Pope, and had him condemned at a Council at Sens in 1140. Abelard appealed

unsuccessfully to Rome against the condemnation, but was ordered to give up

teaching and retire to the Abbey of Cluny. There, two years later, he ended his

days peacefully; his edifying death was described by the Abbot, Peter the Venerable,

in a letter to Héloïse.

Abelard is unusual in the history of philosophy as being also one the world’s

most famous lovers, even if he was tragically forced into the celibacy which is

more typical of great philosophers, whether medieval or modern. It is as a lover,

an ill-fated Lancelot or Romeo, rather than a philosopher, that he has been

celebrated in literary classics. In Pope’s Epistle of Héloïse to Abelard, Héloïse, from

her chill cloister, reminds Abelard of the dreadful day on which he lay before her,

a naked lover bound and bleeding; she pleads with him not to forsake their love.

Come! with thy looks, thy words, relieve my woe;

Those still at least are left thee to bestow.

Still on that breast enamour’d let me lie,

Still drink delicious poison from thy eye

Pant on thy lip, and to thy heart be prest;

Give all thou canst – and let me dream the rest.

Ah no! instruct me other joys to prize

With other beauties charm my partial eyes,

Full in my view set all the bright abode

And make my soul quit Abelard for God.

Abelard’s Logic

Abelard’s importance as a philosopher is due above all to his contribution to logic

and the philosophy of language. Logic, when he began his teaching career, was

studied in the West mainly from Aristotle’s Categories and On Interpretation, plus

Porphyry’s introduction and some works of Cicero and Boethius. Aristotle’s major

logical works were not known, nor were his physical and metaphysical treatises.

Abelard’s logical researches, therefore, were less well informed than those, say, of

Avicenna; but he was gifted with remarkable insight and originality. He wrote

three separate treatises of Logic over the period from 1118 to 1140.

A major interest of twelfth-century logicians was the problem of universals: the

status of a word like ‘man’ in sentences such as ‘Socrates is a man’, and ‘Adam is

a man’. Abelard was a combative writer, and describes his own position on the

issue as having evolved out of dissatisfaction with the answer given by successive

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM135

early medieval philosophy

136

teachers to the question: what is it that, according to these sentences, Adam and

Socrates have in common? Roscelin, his first teacher, said that all they had in

common was the noun – the mere sound of the breath in ‘man’. He was, as later

philosophers would say, a nominalist, nomen being the Latin word for ‘noun’.

William of Champeaux, Abelard’s second teacher, said that there was a very

important thing which they had in common, namely the human species. He was,

in the later terminology, a realist, the Latin word for ‘thing’ being res.

Abelard rejected the accounts of both his teachers, and offered a middle way

between them. On the one hand, it was absurd to say that Adam and Socrates

had only the noun in common; the noun applied to each of them in virtue of

their objective likeness to each other. On the other hand, a resemblance is not

a substantial thing like a horse or a cabbage; only individual things exist, and it

would be ridiculous to maintain that the entire human species was present in each

individual. We must reject both nominalism and realism.

When we maintain that the likeness between things is not a thing, we must avoid it

seeming as if we were treating them as having nothing in common; since what in

fact we say is that the one and the other resemble each other in their being human,

that is, in that they are both human beings. We mean nothing more than that they

are human beings and do not differ at all in this regard.

Their being human, which is not a thing, is the common cause of the application

of the noun to the individuals.

The dichotomy posed by nominalists and realists is, Abelard showed, an in-

adequate one. Besides words and things, we have to take into account our own

understanding, our concepts: it is these which enable us to talk about things, and

turn vocal sounds into meaningful words. There is no universal man distinct from

the universal noun ‘man’; but the sound ‘man’ is turned into a universal noun by

our understanding. In the same way, Abelard suggests, a lump of stone is turned

into a statue by a sculptor; so we can say, if we like, that universals are created by

the mind just as we say that a statue is created by its sculptor.

It is our concepts which give words meaning – but meaning itself is not, for

Abelard, a simple notion. He makes a distinction between what a word signifies

and what it stands for. Consider the word ‘boy’. Wherever this occurs in a sen-

tence, it signifies the same (‘young human male’). In ‘a boy is running across the

grass’, where it occurs in the subject, it also stands for a boy; whereas in ‘this old

man was a boy’, where it occurs in the predicate, it does not stand for anything.

Roughly speaking, ‘boy’ stands for something in a given context only if, in that

context, it makes sense to ask ‘which boy?’

Abelard’s treatment of predicates shows many original logical insights. Aristotle,

and many philosophers after him, worried about the meaning of ‘is’ in ‘Socrates

is wise’ or ‘Socrates is white’. Abelard thinks this is unnecessary: we should regard

‘to be wise’ or ‘to be white’ as a single verbal unit, with the verb ‘to be’ simply

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM136

early medieval philosophy

137

as part of the predicate. What of ‘is’ when it is equivalent to ‘exists’? Abelard says

that in the sentence ‘A father exists’ we should not take ‘A father’ as standing for

anything; rather, the sentence is equivalent to ‘Something is a father’. This pro-

posal of Abelard’s contained great possibilities for the development of logic, but

they were not properly followed up in the Middle Ages, and the device had to

await the nineteenth century to be reinvented.

Abelard’s Ethics

Abelard was an innovator in ethics no less than in logic. He was the first medieval

writer to give a treatise the title Ethics, and unlike his medieval successors he did

not have Aristotle’s Ethics to take as a starting point. But here his innovations

were less happy. Abelard objected to the common teaching that killing people or

committing adultery was wrong. What is wrong, he said, is not the action, but

the state of mind in which it is done. It is incorrect, however, to say that what

matters is a persons’s will, if by ‘will’ we mean a desire for something for its own

sake. There can be sin without will (as when a fugitive kills in self-defence) and

there can be bad will without sin (such as lustful desires one cannot help). True,

all sins are voluntary in the sense that they are not unavoidable, and that they are

the result of some desire or other (e.g. the fugitive’s wish to escape). But what

really matters, Abelard says, is the sinner’s intention or consent, by which he

means primarily the sinner’s knowledge of what he is doing. He argues that since

one can perform a prohibited act innocently – e.g. marry one’s sister unaware that

she is one’s sister – the evil must be not in the act but in the consent. ‘It is not

what is done, but with what mind it is done, that God weighs; the desert and

praise of the agent rests not in his action but in his intention.’

Thus, Abelard says, a bad intention may ruin a good act. Two men may hang

a criminal, one out of zeal for justice, the other out of inveterate hatred; the act

is just, but one does well, the other ill. A good intention may justify a prohibited

action. Those who were cured by Jesus did well to disobey his order to keep the

cure secret, for their motive in publicizing it was a good one. God himself,

when he ordered Abraham to kill Isaac, performed a wrong act with a right

intention.

A good intention not carried out may be as praiseworthy as a good action: if,

for instance, you resolve to build an almshouse, but are robbed of your money.

Similarly, bad intentions are as blameworthy as bad actions. Why then punish

actions rather than intentions? Human punishment, Abelard replies, may be jus-

tified where there is no guilt; a woman who has overlain her infant unawares is

punished to make others more careful. The reason we punish actions rather than

intentions is that human frailty regards a more manifest evil as being a greater

evil. But God will not judge thus.

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM137

early medieval philosophy

138

Abelard’s teaching did not exactly amount to ‘It doesn’t matter what you do as

long as you’re sincere’, but it did come very close to allowing that the end could

justify the means. But what most shocked his contemporaries was his claim that

those who, in good faith, persecuted Christians – indeed those who killed Christ

himself, not knowing what they did – were free from sin. This thesis was made

the subject of one of the condemnations of Sens.

Abelard experimented in theology no less recklessly than in ethics. One example

must suffice: his novel treatment of God’s almighty power. He raised the questions

whether God can make more things, or better things, than the things he has made,

and whether he can refrain from acting as he does. Whichever way we answer, he

said, we find ourselves in difficulty.

On the one hand, if God can make more and better things than those he has

made, is it not mean of him not to do so? After all, it costs him no effort!

Whatever he does or leaves undone is right and just; hence it would be unjust

for him to have acted otherwise than he has done. So he can only act as he has in

fact acted.

On the other hand, if we take any sinner on his way to damnation, it is clear

that he could be better than he is; for if not, he is not to be blamed for his sins.

But he would be better than he is only if God were to make him better; so there

are at least some things which God can make better than he has.

Abelard opts for the first horn of the dilemma. Suppose it is now not raining.

Since this has come about by the will of the wise God, it must now not be a

suitable time for rain. So if we say God could now make it rain, we are attributing

to him the power to do something foolish. Whatever God wants to do he can;

but if he doesn’t want to do something, then he can’t.

Critics objected that this thesis was an insult to God’s power: even we poor

creatures can act otherwise than we do. Abelard replied that the power to act

otherwise is not something to be proud of, but a mark of infirmity, like the ability

to walk, eat, and sin. We would all be better off if we could only do what we

ought to do.

What of the argument that the sinner will be saved only if God saves him,

therefore if the sinner can be saved God can save him? Abelard rejects the logical

principle which underlies the argument, namely, that if p entails q, then possibly

p entails possibly q. He gives a counterexample. If a sound is heard, then some-

body hears it; but a sound can be audible without anyone being able to hear it.

(Maybe there is no one within earshot.)

Abelard’s discussion of omnipotence is a splendid piece of dialectic; but it

cannot be said to amount to a credible account of the concept, and it certainly

did not convince his contemporaries, notably St Bernard. One of the propositions

condemned at the Council of Sens was this: God can act and refrain from acting

only in the manner and at the time that he actually does act and refrain from

acting, and in no other way.

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM138

early medieval philosophy

139

Averroes

Abelard was far the most brilliant Christian thinker of the twelfth century. The

other significant philosophers of the age were the Arab Averroes and the Jew

Maimonides. Both of them were natives of Cordoba in Muslim Spain, then the

foremost centre of artistic and literary culture in the whole of Europe.

Averroes’ real name was Ibn Rushd. He was born in 1126, the son and grand-

son of lawyers and judges. Little certain is known about his education, but he

acquired a knowledge of medicine which he incorporated into a textbook called

Kulliyat. He travelled to Marrakesh, where he secured the patronage of the

sultan. The sighting there of a star not visible in Spain convinced him of the truth

of Aristotle’s claim that the world was round. He acquired a great enthusiasm for

all of Aristotle’s philosophy, and the caliph encouraged him to begin work on a

series of commentaries on the philosopher’s treatises.

In 1169 Averroes was appointed a judge in Seville; later he returned to

Cordoba and was promoted to chief judge. However, he retained his links with

Marrakesh, and went back there to die in 1198, having fallen under suspicion

of heresy.

Earlier in his life, Averroes had had to defend his philosophical activities against

a more conservative Muslim thinker, Al-Ghazali, who had written an attack on

rationalism in religion, entitled The Incoherence of the Philosophers. Averroes re-

sponded with The Incoherence of the Incoherence, asserting the right of human

reason to investigate theological matters.

Averroes’ importance on the history of philosophy derives from his comment-

aries on Aristotle (see Plate 8). These came in three sizes: short, intermediate, and

long. For some of Aristotle’s works all three commentaries are extant, for some

two, and for some only one; some survive in the original Arabic, some in transla-

tions into Hebrew and Latin. Averroes also commented on Plato’s Republic, but

his enormous admiration for Aristotle (‘his mind is the supreme expression of the

human mind’) did not extend in the same degree to Plato. Indeed, he saw it as

one of his tasks as a commentator to free Aristotle from Neo-Platonic overlay,

even though in fact he preserved more Platonic elements than he realized.

Averroes was not an original thinker like Avicenna, but his encyclopaedic work

was to prove the vehicle through which the interpretation of Aristotle was medi-

ated to the Latin Middle Ages. His desire to free Aristotle from later accretions

made him depart from Avicenna in a number of ways. Thus, he abandoned the

series of emanations which in Avicenna led from the first cause to the active intel-

lect, and he denied that the active intellect produced the natural forms of the visible

world. But in one respect he moved further away than Avicenna from the most

plausible interpretation of Aristotle. After some hesitation, he reached the con-

clusion that neither the active intellect nor the passive intellect is a faculty of

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM139

early medieval philosophy

140

individual human beings; the passive intellect, no less than the active, is a single,

eternal, incorporeal substance. This substance intervenes, in a mysterious way, in

the mental life of human individuals. It is only because of the role played in our

thinking by the individual corporeal imagination that you and I can claim any

thoughts as our own.

Because the truly intellectual element in thought is non-personal, there is no

personal immortality for the individual human being. After death, souls merge

with each other. Averroes argues for this in a manner which resembles the Third

Man argument in Plato’s Parmenides.

Zaid and Amr are numerically different but identical in form. If, for example, the

soul of Zaid were numerically different from the soul of Amr in the way Zaid is

numerically different from Amr, the soul of Zaid and the soul of Amr would be

numerically two, but one in their form, and the soul would possess another soul.

The necessary conclusion is therefore that the soul of Zaid and the soul of Amr are

identical in their form. An identical form inheres in a numerical, i.e. a divisible

multiplicity, only through the multiplicity of matter. If then the soul does not die

when the body dies, or if it possesses an immortal element, it must, when it has left

the body, form a numerical unity.

At death the soul passes into the universal intelligence like a drop into the sea.

Averroes was, at least in intention, an orthodox Muslim. In his treatise On the

Harmony between Religion and Philosophy he spoke of several levels of access to

the truth. All classes of men need, and can assimilate, the teaching of the Prophet.

The simple believer accepts the literal word of Scripture as expounded by his

teachers. The educated person can appreciate probable, ‘dialectical’ arguments

in support of revelation. Finally, that rare being, the genuine philosopher, needs,

and can find, compelling proofs of the truth. This doctrine was crudely misunder-

stood by Averroes’ intellectual posterity as a doctrine of double truth: the doctrine

that something can be true in philosophy which is not true in religion, and vice

versa.

Averroes made little mark on his fellow Muslims, among whom his type of phi-

losophy rapidly fell into disfavour. But after his writings had been translated into

Latin, his influence was very great: he set the agenda for the major thinkers of the

thirteenth century, including Thomas Aquinas. Dante gave him an honoured place

in his Inferno as the author of the great commentary; and Aristotelian scholars,

for centuries, referred to him simply as the Commentator.

Maimonides

Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, better known to later writers by the name of

Maimonides, was nine years younger than Averroes. He left his birthplace,

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM140

early medieval philosophy

141

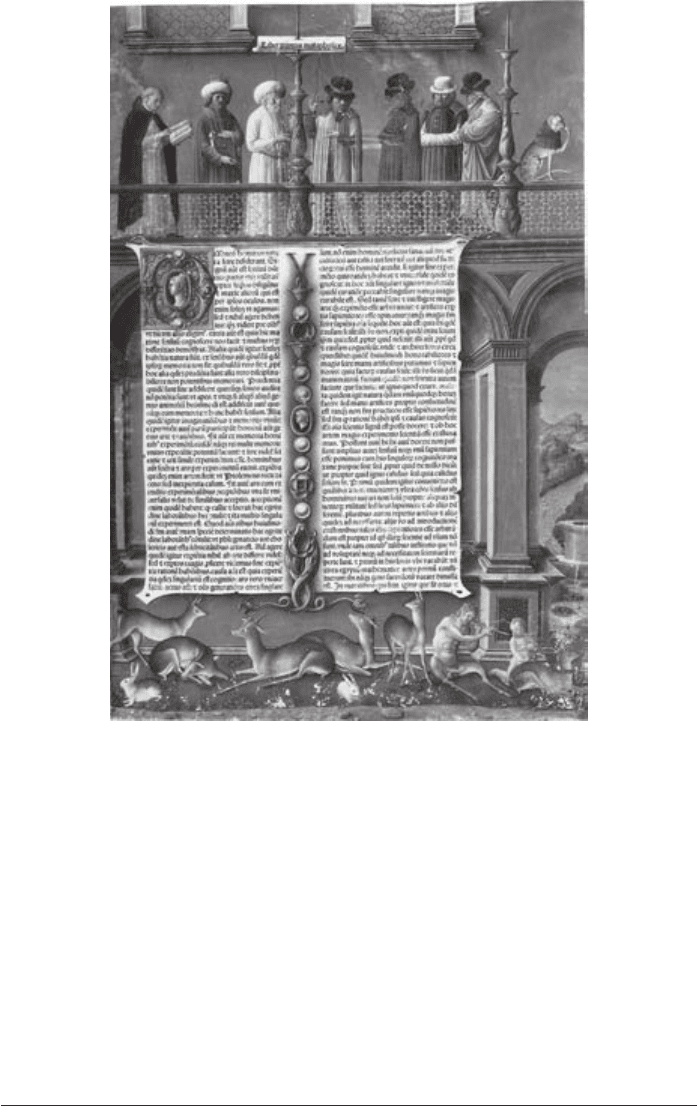

Figure 18 In this fifteenth-century edition of Aristotle’s Metaphysics we see the

Philosopher surrounded by Jewish, Muslim, and Christian followers.

(Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, PML 21195)

Cordoba, when thirteen. Muslim Spain, which had provided a tolerant environ-

ment for Jews hitherto, was overrun by the fanatical Almohads, and Maimonides’

family migrated to Fez and later to Palestine. For the last forty years of his life he

lived in Egypt, and he died in Cairo in 1204.

Maimonides wrote copiously, in both Hebrew and Arabic, on rabbinic law and

on medicine, but as a philosopher he is known for his book The Guide for the

Perplexed, which was designed to reconcile the apparent contradictions between

philosophy and religion which troubled believers. Much of the Bible, he thought,

would be harmful if interpreted in a literal sense, and philosophy is necessary to

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM141

early medieval philosophy

142

determine its true meaning. We cannot say anything positive about God, since he

has nothing in common with creatures like us. He is a simple unity, and does not

have distinct attributes such as justice and wisdom. When we attach predicates to

the divine name, as when we say ‘God is wise’, what we are really doing is saying

what God is not; we mean that God is not foolish. (Foolishness, unlike divine

wisdom, is something of which we have ample experience.)

The meaning of ‘knowledge’ the meaning of ‘purpose’ and the meaning of ‘pro-

vidence’, when ascribed to us, are different from the meanings of these terms when

ascribed to Him. When the two providences or knowledges or purposes are taken to

have one and the same meaning, difficulties and doubts arise. When, on the other

hand, it is known that everything that is ascribed to us is different from everything

that is ascribed to Him, truth becomes manifest. The differences between the things

ascribed to Him and those ascribed to us are expressly stated in the text Your ways

are not my ways. (Isaiah 55: 8)

This ‘negative theology’ was to have great influence on Christian as well as Jewish

philosophers.

The only positive knowledge of God which is possible for human beings – even

for so favoured a man as Moses – is knowledge of the workings of the natural

world which is governed by him. We are not to think, however, that God’s

governance is concerned with every individual event in the world; his providence

concerns human beings individually, but concerns other creatures only in general.

Divine providence watches only over the individuals belonging to the human spe-

cies, and in this species alone all the circumstances of the individuals and the good

and evil that befall them are consequent upon their deserts. But regarding all the

other animals and, all the more, the plants and other things, my opinion is that of

Aristotle. For I do not at all believe that this particular leaf has fallen because of a

providence watching over it . . . nor that the spittle spat by Zayd has moved till it

came down in one particular place upon a gnat and killed it by a divine decree. . . . All

this is in my opinion due to pure chance, just as Aristotle holds.

Maimonides’ account of the structure and operation of the natural world was

indeed taken largely from Aristotle, ‘the summit of human intelligence’. But as a

believer in the Jewish doctrine that the world was created within time to fulfil a

divine purpose, he rejected the Aristotelian conception of an eternal universe with

fixed and necessary species. It is disgraceful to think, he says, that God could not

lengthen the wing of a fly.

The aim of life, for Maimonides, is to know, love, and imitate God. Both the

prophet and the philosopher can come to the knowledge of whatever can be

known about God, but the prophet can do so more swiftly and surely. Know-

ledge is to lead to love, and love finds expression in the passionless imitation of

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM142

early medieval philosophy

143

divine action which we find in the accounts of the prophets and lawgivers in the

Bible. Those who are not gifted with prophetic or philosophical knowledge have

to be kept under control by beliefs which are not strictly true, such as that God

is prompt to answer prayer and is angry at sinners’ wrongdoing.

Like Abelard among the Christians and Averroes among the Muslims,

Maimonides was accused by his co-religionists of impiety and blasphemy. Such

was the common fate of philosophical speculation by religious thinkers in the

twelfth century. Christendom in the thirteenth century will offer something new:

a series of philosophers of the first rank who were also venerated as saints in their

own religious community.

AIBC07 22/03/2006, 11:01 AM143