Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.2 Chirality 149

make other compounds—we will often use chiral molecules to provide the level

of detail necessary to work out how reactions occur. Moreover, because most of

the molecules of Nature are chiral, an understanding of chirality is essential to vir-

tually all of biochemistry and molecular biology.

You are very strongly urged to work through this chapter with models. It is a

rare person who can see easily in three dimensions without a great deal of practice.

ESSENTIAL SKILLS AND DETAILS

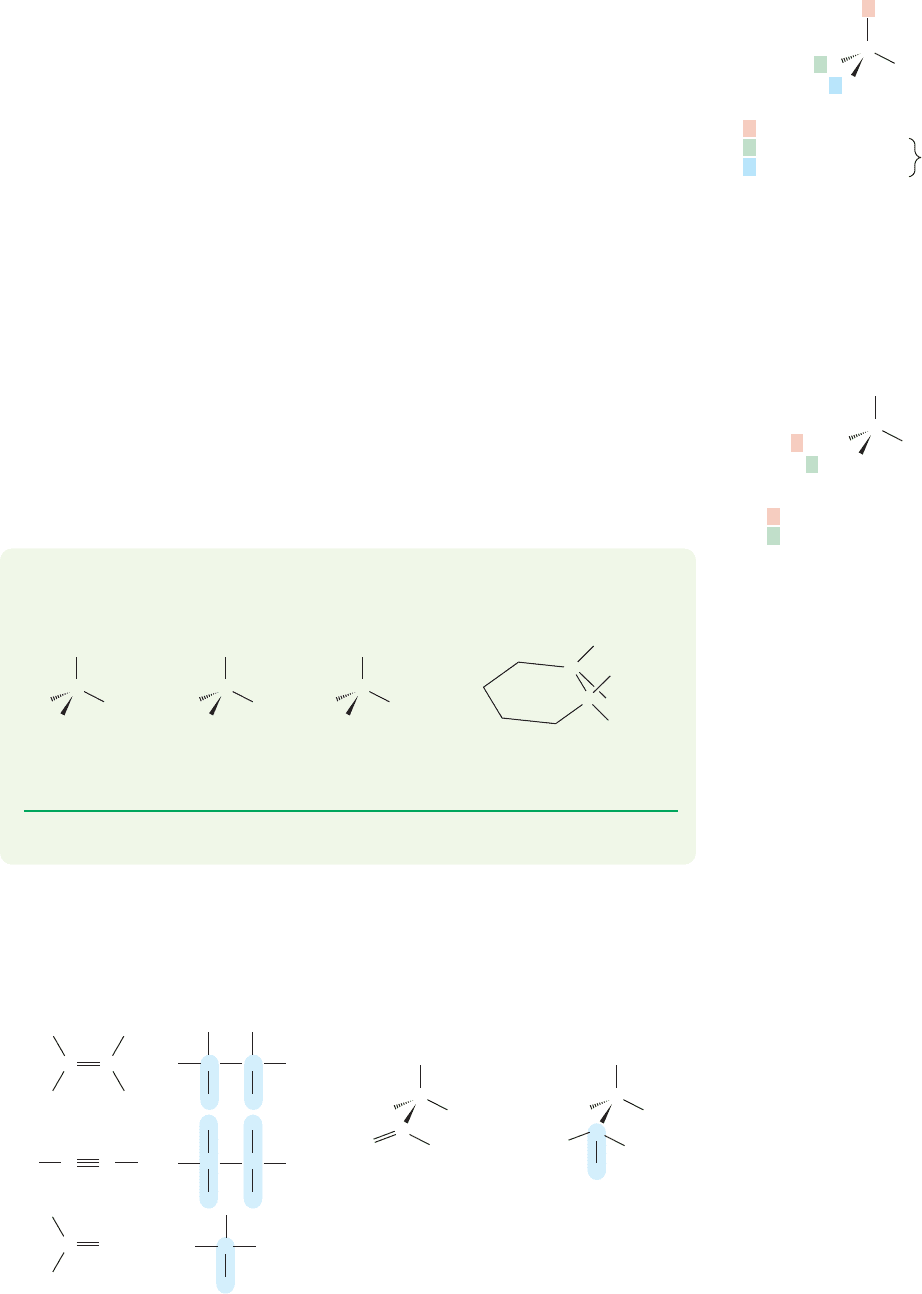

1. Sidedness and Handedness. You have the broad outlines of structure under control

now—acyclic alkanes, alkenes, and alkynes have appeared, as have rings. Now we come

to the details, to stereochemistry. “Sidedness”—cis/trans isomerism—is augmented by

questions of chirality—“handedness.”Learning to see one level deeper into three-

dimensionality is the next critical skill.

2. Difference.The topic of difference and how difference is determined arises in this

chapter. The details may be nuts and bolts, and, indeed, any way that you work out to

do the job will be just fine, but there is no avoiding the seriousness of the question.

When are two atoms the same (in exactly the same environment) or different (not in

the same environment)? This question gets to the heart of structure and is much

tougher to answer than it seems. By all means, concentrate on this point. This chapter

will help you out by introducing a method—an algorithm for determining whether or

not two atoms are in different environments. It is well worth knowing how it works.

3. There is no way out—the (R) and (S) priority system must be learned.

4. Words—Jargon. This chapter is filled with jargon: Be certain that you learn the

difference between enantiomers and diastereomers. Learn also what “stereogenic,”

“chiral,” “racemic,” and “meso” mean.

4.2 Chirality

The phenomenon of handedness, or chirality, actually surfaces long before we

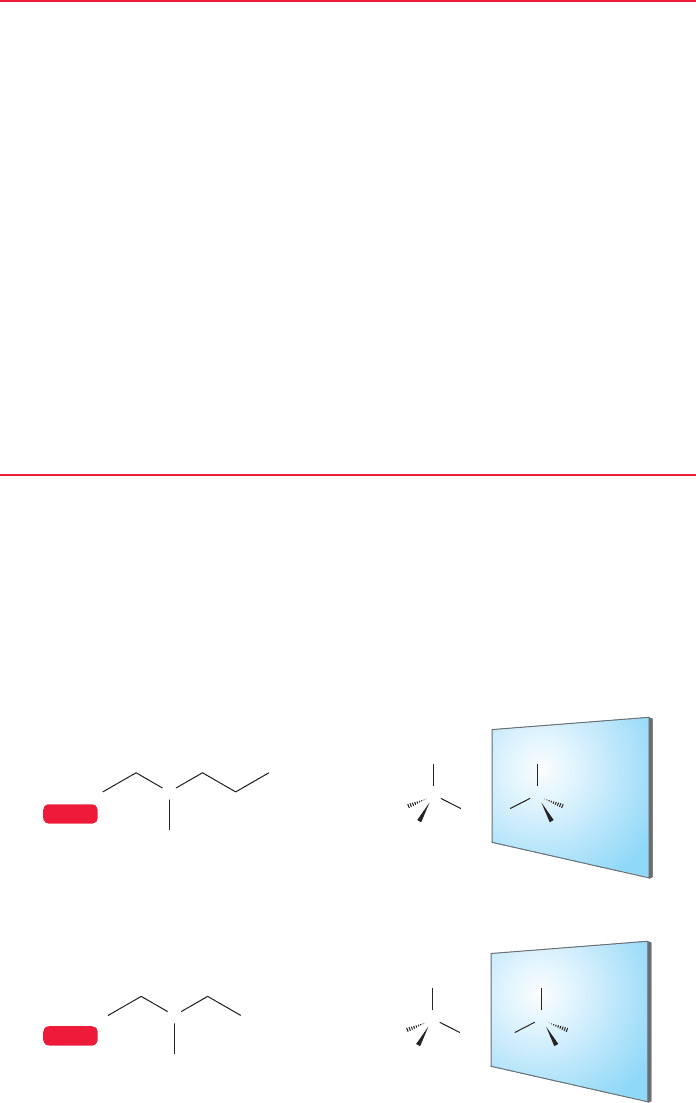

encounter a molecule as complicated as trans-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane. We went

right past it when we wrote out the heptane isomers in Figure 2.45 (p. 82). One of

these heptanes, 3-methylhexane, exists in two forms. To see this, draw out the

molecule in tetrahedral form using C(3) as the center of the tetrahedron (Fig. 4.2a).

Mirror

Mirror

H

C

H

3

CH

3

C

=

3-Methylhexane and its mirror image

3-Meth

y

l

p

entane and its mirror ima

g

e

3-Methylhexane

3-Methylpentane

C

H

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

H

CH

3

C

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

H

C

=

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

H

CH

3

C

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

C

C

3

33

3

33

WEB 3D

WEB 3D

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 4.2 3-Methylhexane (a) and

3-methylpentane (b) reflected to

show their mirror images.

150 CHAPTER 4 Stereochemistry

Mirror

Mirror

H

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

C

180 rotation

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

H

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

H

CH

3

C

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

Rotate 180

about the

C CH

3

bond

These structures are identical; there is only one 3-methylpentane

H

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

H

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

H

CH

3

C

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

Rotate in the plane

of the paper

These structures are not superimposable without

further rotation, but they are still identical, and

can be made superimposable by further rotation

(a)

(b)

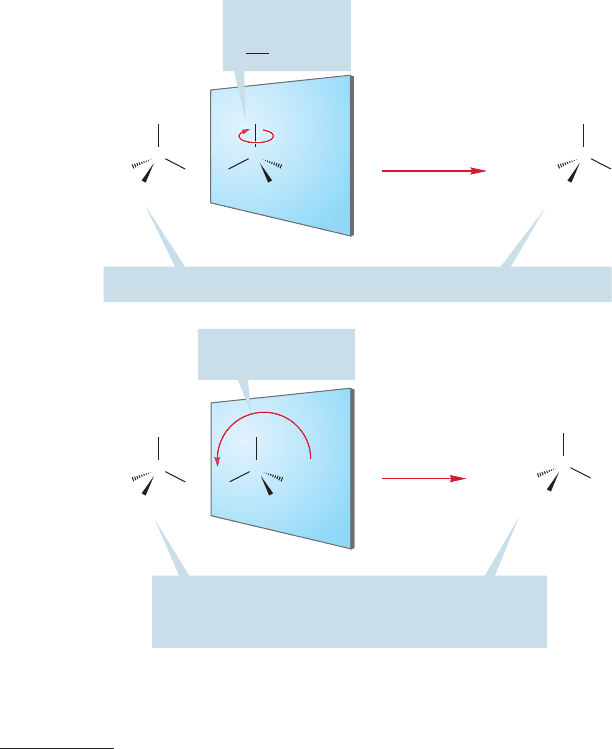

FIGURE 4.3 (a) 3-Methylpentane and

its mirror image are identical. Rotate

the mirror image at the top of the figure

180° about the carbon–methyl bond

to see this point. (b) Although motion

that produces a nonsuperimposable

mirror image tells us nothing about

the chirality of the molecule, a motion

that produces a superimposable

mirror image tells us that the

molecule is not chiral (achiral).

Next, draw the mirror image of this molecule. Compare these structures with

3-methylpentane treated the same way, with C(3) still the center of the

tetrahedron (Fig. 4.2b).

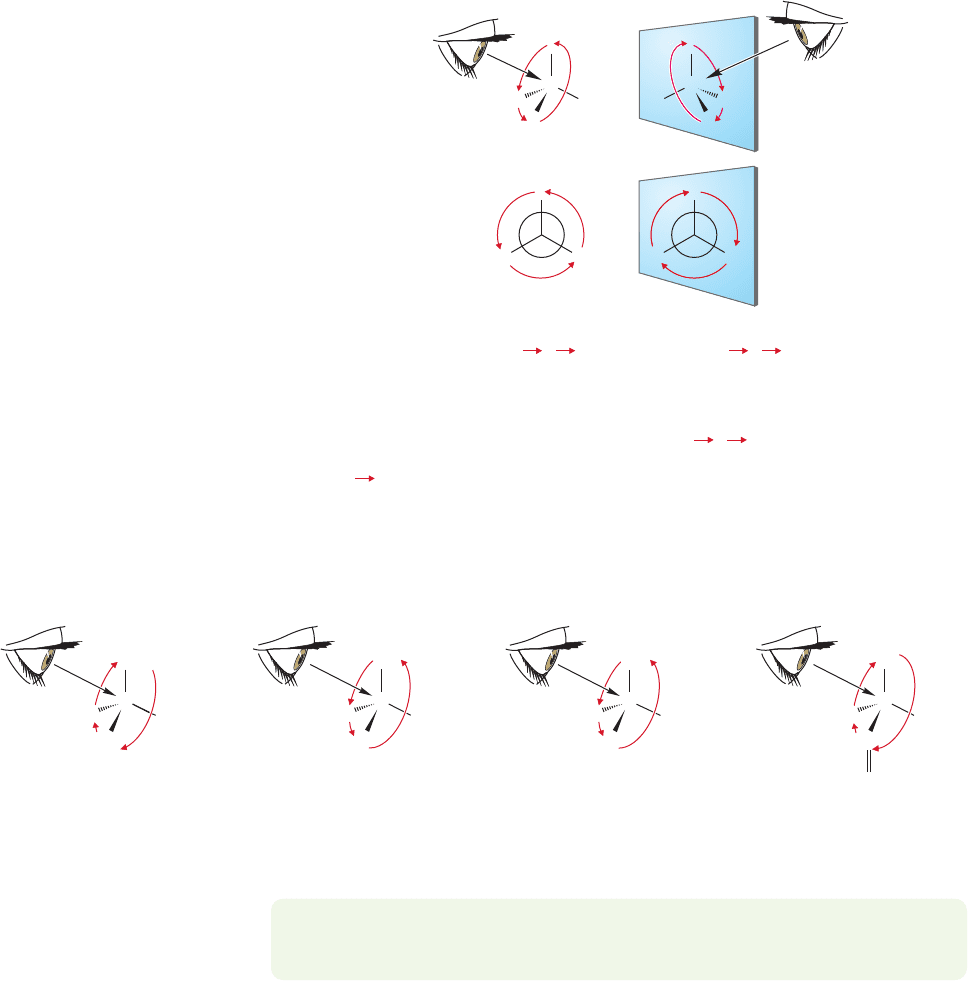

Now see if the reflections—the mirror images—are the same as the origi-

nals. For 3-methylpentane, one need only rotate the molecule 180° around the

bond, and slide it over to the left to superimpose it on the origi-

nal molecule (Fig. 4.3a). The molecule and its mirror image are clearly identi-

cal, and hence, 3-methylpentane is achiral (not chiral).

2

However, Nature seems

to lay a trap for us, as there are many motions of the mirror image that will not

directly generate a molecule superimposable on the original. In such cases, we

may be led to think we have uncovered chirality. For example, try rotating

3-methylpentane as shown in Figure 4.3b. The original and the newly rotated

molecule are not superimposable as drawn. But chiral? No, for as long as there

is one motion (Fig. 4.3a, top) that does generate the mirror image, the molecule

is achiral.

C(3)

O

CH

3

2

There is a language problem introduced by the choice of the Greek word chiral to describe the phenomenon

of handedness of molecules. In Greek, the word for not chiral is achiral. This poses no problem in Greek,

but, at least in spoken English it does. It is often difficult to distinguish between “Compound X is a chiral

molecule” and “Compound X is achiral.”

4.2 Chirality 151

Models are essential now,as you must be absolutely certain of the difference between

3-methylpentane and 3-methylhexane. The more symmetric 3-methylpentane is

achiral, whereas 3-methylhexane and your hand are chiral. The two stereoisomers of

3-methylhexane are related in exactly the same way your two hands are.A chiral com-

pound can be defined as a molecule for which the mirror image is not superimpos-

able on the original. The two nonsuperimposable mirror images of 3-methylhexane

are examples of enantiomers.

Our next tasks are to learn how to differentiate enantiomers in words (we do

have to be able to talk to each other!) and to see how these stereoisomers differ phys-

ically.Which physical properties do enantiomers share and which are different? This

topic leads us to a brief discussion of how the physical differences arise. Next, we

explore how enantiomers differ chemically. Which chemical properties are shared

by enantiomers and which are different? Next, we need to explore the circumstances

under which chirality will appear.What structural features will suffice to ensure chi-

rality? Will, for example, the phenomenon we see in Figure 4.5 of four different

groups surrounding a carbon be a sufficient condition to ensure chirality? Will it be

a necessary condition? This chapter discusses such questions.

Now consider Figure 4.4. Here we apply to 3-methylhexane the same rotation

that we applied before to 3-methylpentane. In this case, we cannot superimpose the

original molecule onto the newly rotated molecule no matter how many ways we

try. The propyl group in one form winds up where the ethyl group is in the other.

Indeed, no amount of twisting and turning can do the job: The two are irrevocably

different. 3-Methylhexane is chiral.

Mirror

H

C

H

3

C

180⬚ rotation

C

H

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

H

C

H

3

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

H

CH

3

C

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

These mirror images are not the same, even after

rotation! There are two distinct 3-methylhexanes

3

3

3

FIGURE 4.4 3-Methylhexane and its

mirror image are not identical.

CH

3

Mirror Mirror

3-Methylhexane

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

=

CHC

CHH

CH

3

3-Methylpentane

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

=

CHC

CHH

FIGURE 4.5 3-Methylhexane, 3-methylpentane, and their mirror images.

PROBLEM 4.1 Are the following molecules chiral? (a) bromochlorofluoroiodomethane,

(b) dibromochlorofluoromethane, (c) 3-methylheptane, (d) 4-methylheptane

152 CHAPTER 4 Stereochemistry

4.3 The (R/S) Convention

3

The word “stereogenic,”though officially suggested in 1953, came into general use only recently when it was

urged by Princeton professor Kurt M. Mislow (b. 1923) as a replacement for a plethora of unsatisfactory

terms such as “chiral carbon,” “asymmetric carbon (or atom),” and many others. These old terms are slowly

disappearing, but will persist in the literature (and textbooks) for many more years.

In order to specify the absolute configuration of a molecule, the three-dimensional

arrangement of its atoms, one first identifies the stereogenic center, very often a

carbon atom.

3

A stereogenic atom can be simply defined as follows: “An atom

(usually carbon) of such nature and bearing groups of such nature that it can have

two nonequivalent configurations,” in other words, having a stereogenic atom

means enantiomers can exist.

In our example of 3-methylhexane,the stereogenic carbon, C(3),is the one upon

which we based the tetrahedral structures of Figures 4.2–4.5. Next, one identifies

the four groups (atoms or groups of atoms) attached to the stereogenic carbon and

gives them priorities according to the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog scheme we first met in

Chapter 3 (p. 111) when we discussed Z/E (cis/trans) isomerism. The system is

applied here so that any stereogenic atom can be designated as either (R) or (S) from

a consideration of the priorities of the attached groups (1 high, 4 low). The

application of the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog scheme to determine (R) or (S) is a bit more

complicated than that for determining (Z) or (E) for alkenes, so the system will be

summarized again here.

The atom of lowest atomic number is given the lowest priority number, 4. In

3-methylhexane, this atom is hydrogen (Fig.4.6a). In some molecules, one can give

priority numbers to all the atoms by simply ordering them by atomic number.Thus,

bromochlorofluoromethane is easy: H is 4, F is 3, Cl is 2, and Br is 1 (Fig. 4.6b).

The priorities are assigned in order of increasing atomic number so that the high-

est priority, 1, is given to the atom of highest atomic number, in this case bromine

(Fig. 4.6b).

A subrule is illustrated by another easy example, 1-deuterioethyl alcohol

(Fig. 4.7). We break the tie between the isotopes H and D by assigning the lower

priority number to the atom of lower mass, H. So H is 4; D is 3; C is 2; and O,

with the highest atomic number, is priority 1.

There can be more difficult ties to break, however. The molecule sec-butyl alco-

hol (2-hydroxybutane) illustrates this point.The lowest priority, 4,is H and the high-

est priority, 1, is O. But how do we choose between the two carbons shown in red

in Figure 4.8? The tie is broken by working outward from the tied atoms until a dif-

ference is found. In this example, it’s easy. The methyl carbon is attached to three

hydrogens and the methylene carbon is attached to two hydrogens and a carbon.

CONVENTION ALERT

(

b

)(

a

)

H

CH

3

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

H

F

C

Br

Cl

3

1

2

4

4

FIGURE 4.6 The atom of lowest

atomic number, often hydrogen, is

given the lowest priority, 4.The

remaining priorities are assigned in

order of increasing atomic number.

H

OH

C

H

3

C

D

4

3

2

1

FIGURE 4.7 When the atomic

numbers are equal, the atomic masses

are used to break the tie.

H

O

H

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

4

1

H

O

H

C

C

H

H

H

3

C

H

3

C

4

1

2

Higher priority—

attached to C,H,H

3

Lower priority—

attached to H,H,H

These are

both carbons—

how do we

break this

priority tie?

FIGURE 4.8 When both the atomic

numbers and the atomic masses are

equal, one looks at the atoms to

which the tied atoms are attached

and determines their atomic

numbers.

4.3 The (R/S) Convention 153

The methyl carbon gets the lower priority number 3 by virtue of the lower atomic

numbers of the atoms attached to it (H,H,H 1,1,1) and the ethyl carbon (attached

to C,H,H 6,1,1) gets the higher priority number, 2 (Fig. 4.8).

Sometimes there will be even more difficult ties to break, and another look at

3-methylhexane illustrates this problem well (Fig. 4.9). It is easy to identify H as

the atom with the lowest atomic number, but the other three atoms are all carbons.

How do we break this tie? We work outward from the identical atoms until a dif-

ference appears. In 3-methylhexane, the methyl group is attached to three hydro-

gens, but each methylene group is attached to two hydrogens and one carbon.

Because H has a lower atomic number than C, the methyl group gets priority num-

ber 3 (Fig. 4.9).

Now we are faced with yet another tie, and must find a way to distinguish the

pair of methylene groups. Again we work outward. Look at the carbons attached to

the two tied methylenes (Fig. 4.10). The red one is a methyl carbon and is attached

to three hydrogens. The green carbon is a methylene carbon and is attached to two

hydrogens and a carbon. The methylene attached to the methyl gets priority 2 and

the other methylene is left with the highest priority, 1. In practice, this detailed

bookkeeping is often unnecessary. In this example, it is really quite easy to see that

the smaller ethyl group is of lower priority than the larger propyl group, and

thus its carbon will get the lower priority number. More difficult examples can be

devised, however!

H

CH

3

C attached to (H,H,H) = 3

C attached to (C,H,H)

C attached to (C,H,H)

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

4

3

Still tied

FIGURE 4.9 An example of a

complicated tie-breaking procedure.

In this case, we start by looking at the

atoms attached to the three tied

carbons. This procedure does not

completely resolve the tie.

H

CH

3

C attached to (H,H,H) = 2

C attached to (C,H,H) = 1

C

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

4

3

2

1

To break this tie look at

the carbons next further

out along the chains

FIGURE 4.10 The final assignment of

priority numbers in 3-methylhexane.

CD

3

H

C

HO

C

H

2

CH

3

CH

3

H

H

H

3

C

CH

3

OH

C

HS

HSe

(a) (b) (c) (d)

CH(CH

3

)

2

Br

C

H

C

C

Note that in (d) there are two stereogenic carbon atoms

C

H

2

CH

3

HOCH

2

=

CC

C C

C

=

CO

C

CC

CC

=

=

CC

C

C

O

CO

H

H

Br

C

C

O

1

4

HOCH

2

H

H

Br

C

O

C

O

1

3

2

4

FIGURE 4.11 Carbon–carbon double

bonds and carbon–carbon triple

bonds are elaborated by adding new

carbon bonds as shown.The

carbon–oxygen double bond is

treated by adding a new bond from

carbon to oxygen. Thus, the carbon is

treated as being attached to one

hydrogen and two oxygens and gets a

higher priority number than the

carbon that is attached to two

hydrogens and one oxygen.

PROBLEM 4.2 Identify the priorities of the groups attached to the stereogenic car-

bons in the compounds in the following figure:

PROBLEM 4.3 Draw the mirror images of the chiral compounds (a–d) in Problem 4.2.

How do we deal with multiple bonds in the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog scheme?

Carbon–carbon double bonds, carbon–carbon triple bonds, and carbon–oxygen

double bonds are treated as shown in Figure 4.11. Hydrogen obviously gets the

lowest priority, 4, and the bromine gets the highest priority, 1. But both the other

substituents on the stereogenic carbon are carbons. The tie is resolved by treating

the carbon atom in the carbon–oxygen double bond as if it were attached to two

oxygens as shown in Figure 4.11. Therefore it gets the higher priority, 2, and the

carbon attached to only one oxygen gets the remaining priority, 3.

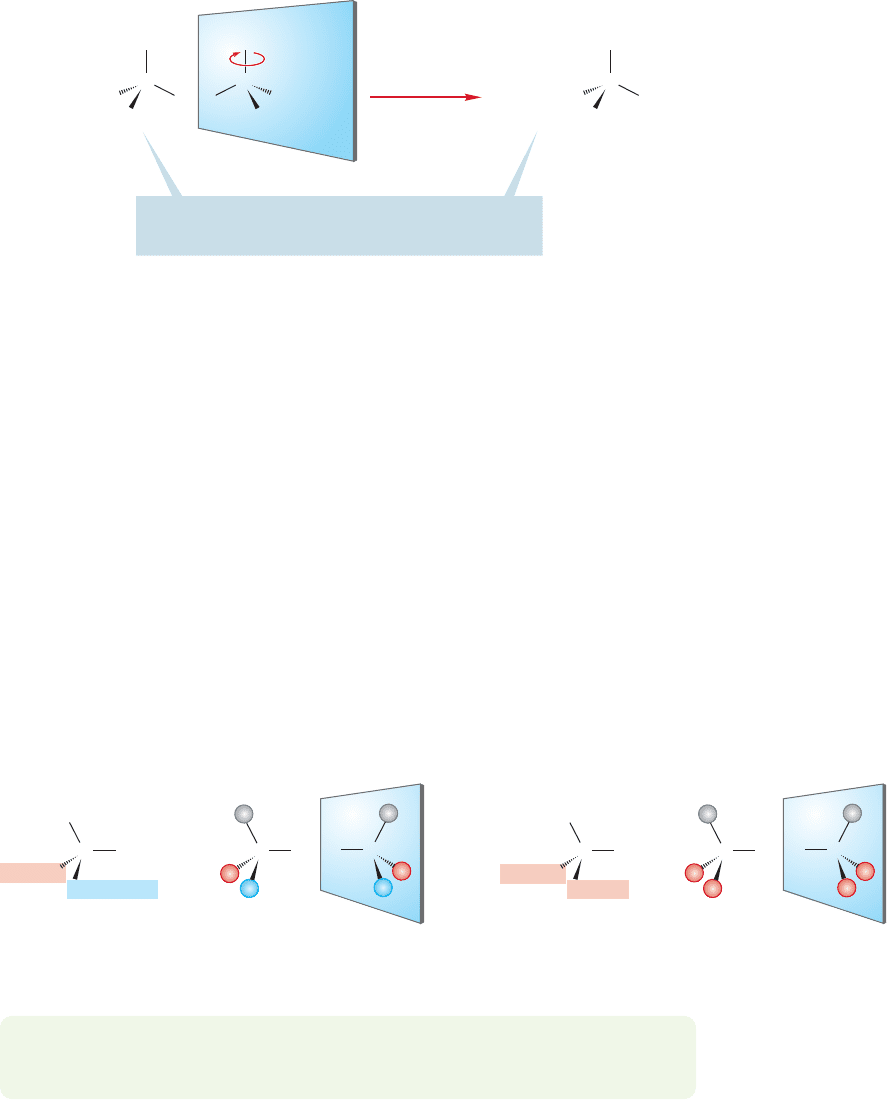

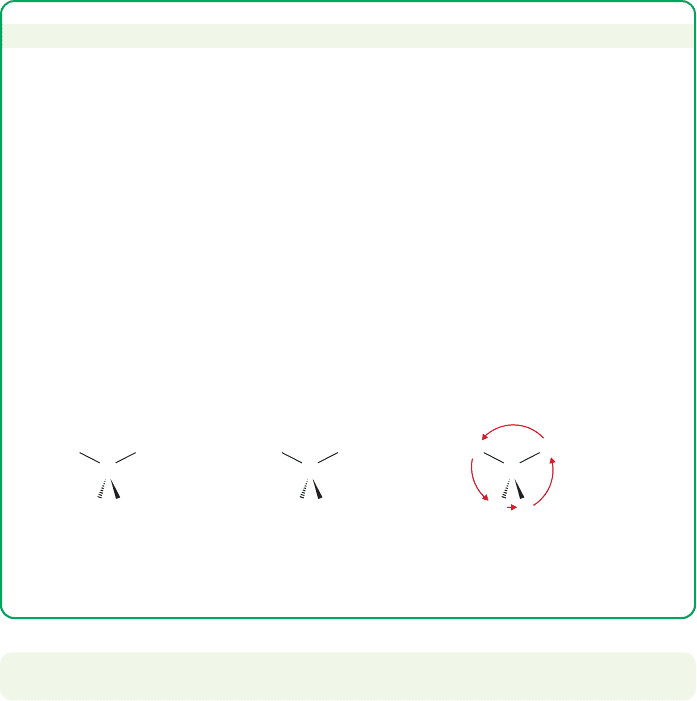

Once priority numbers have been established,the next step in determining absolute

configuration (R or S) is to imagine looking down the bond from the stereogenic atom

(usually carbon) toward the atom of lowest priority (4, often H), as in Figure 4.12.

The other three substituents (1, 2, 3) will be facing you. Connect these three with an

arrow running from highest to lowest priority number (1 2 3).If this arrow runs

clockwise from your perspective, the enantiomer is called (R) (Latin: rectus, “right”);

if it runs counterclockwise,the enantiomer is called (S) (Latin: sinister,“left”) (Fig.4.12).

UU

154 CHAPTER 4 Stereochemistry

Mirror

Mirror

C

(R)(S)

C

(S) Enantiomer;

the arrow 1 2 3

runs counterclockwise

(R) Enantiomer;

the arrow 1 2 3

runs clockwise

1

1

2

3

1

22

33

44

1

3

2

Note that your eye must look from the stereogenic carbon toward priority 4; if you

look in the other direction, or if you draw the arrow 3 2 1, you will get the

convention backward! For clarity, we have completed the circle by drawing the

arrow 3 1

FIGURE 4.12 The (R ) and (S )

naming convention. It often helps to

put the priority 4 in the back.

(R)-3-Methylhexane

3

4

1

2

CH

3

CH

2

C

(S)-1-Deuterioethyl alcohol

1

4

3

H

C

H

CH

3

OH

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

D

H

3

C

2

(S)-sec-Butyl alcohol

1

4

3

2

H

C

(R)-2-Bromo-3-hydroxy-

propanal

1

4

2

3

Br

H

HC

O

C

OH

CH

3

CH

2

H

3

C

HOCH

2

FIGURE 4.13 Some (R ) and (S ) molecules.

The label (R) or (S) is added to the name as an italic prefix in parentheses.Figure 4.13

shows the (R) and (S) forms of some examples from the previous paragraphs.

PROBLEM 4.4 Designate the stereogenic carbons of the compounds in Problem

4.2 as either (R) or (S).

4.4 Properties of Enantiomers: Physical Differences 155

PROBLEM SOLVING

The (R/S) convention is difficult only because it is utterly arbitrary. A bunch of

folks in Europe thought up some conventions and we all use them. You can’t

“think” your way through an (R/S) assignment. You have to know the rules. For

example, you have to look from the stereogenic atom (almost always a carbon)

toward the priority 4 atom (often H). But what if the drawing makes this view

difficult, as in the molecule below? It is easy to assign priorities and draw the

arrow, but the molecule has the H (priority 4) pointing right at us, and it is not

easy to put your eye in the proper position. The “fix” is to look the other (wrong)

way, from priority 4 to the stereogenic C, and to reverse your answer. In this case,

the arrow, seen from the anti-conventional “wrong” direction is counterclockwise,

so the molecule is R.This technique is a bit tricky, because you have to remember

that you are violating the convention, but it is often easier, and safer, than

redrawing the molecule in a different orientation.

Arrow is counterclockwise, but

we are looking “backward!”—

molecule is (R)

C

CH

2

CH

3

Cl H

H

3

C

C

CH

2

CH

3

Cl H

H

3

C

32

41

C

CH

2

CH

3

Cl H

H

3

C

32

41

PROBLEM 4.5 Draw the enantiomers of the molecules in Figure 4.13.

The (R/S) convention looks a bit complicated. It is easier than it appears right

now, but it just must be learned, and cannot be reasoned out. It’s quite arbitrary

at a number of points. For the price of learning this convention we get the

return of being able to specify great detail most economically. Time and again

we will use the subtle differences between enantiomers to test ideas about

reaction mechanisms—of how chemical reactions occur.The study of the effects

of stereochemistry on reaction mechanisms has been, and remains, one of the

most powerful tools used by chemists to unravel how Nature works. Practice

using the (R/S) convention and it will become easy. It’s well worth it—indeed,

it’s essential.

4.4 Properties of Enantiomers:

Physical Differences

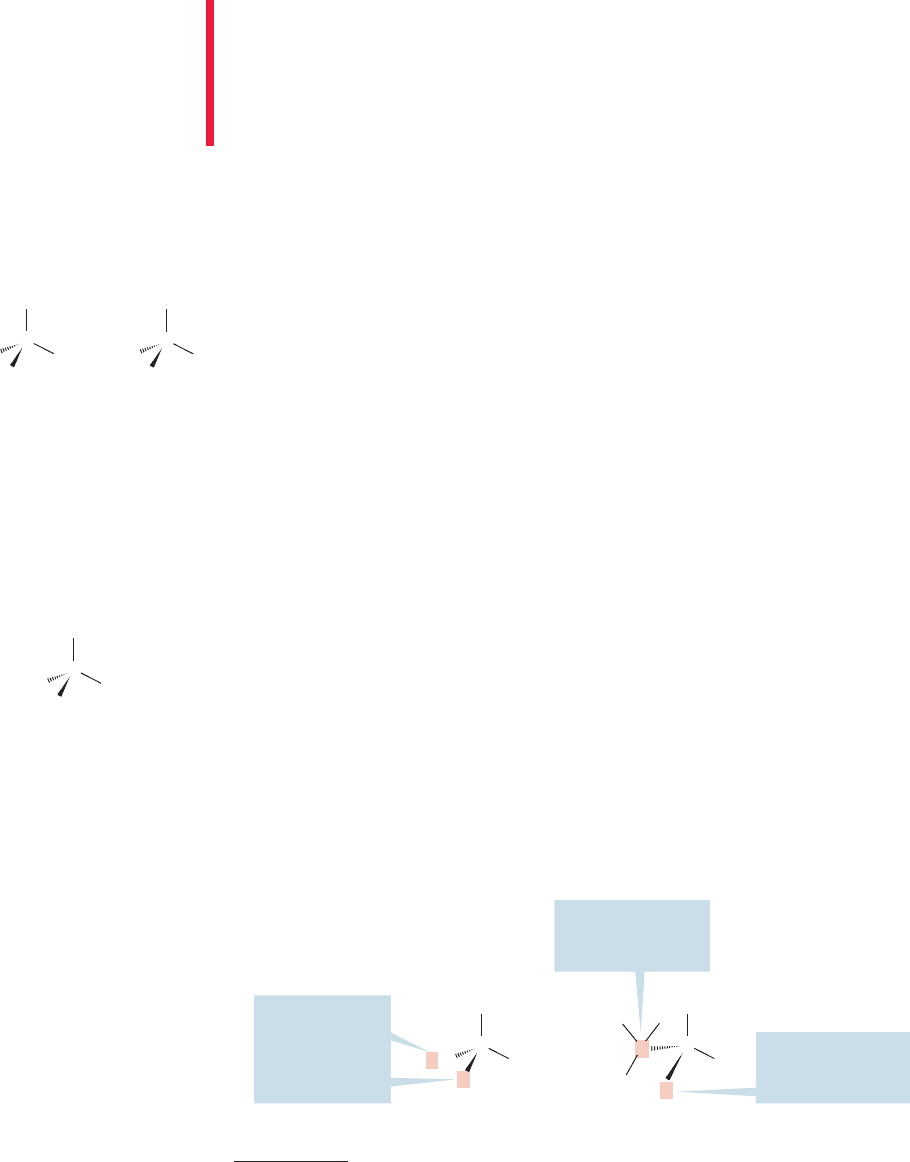

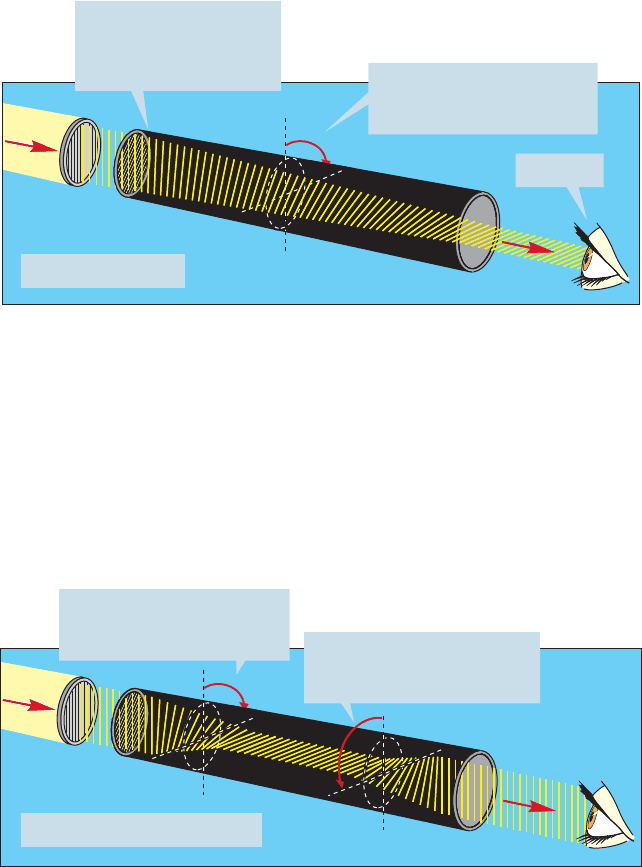

Almost all physical properties of enantiomers are identical.Their melting points,

boiling points, densities, and many other physical properties do not serve to dis-

tinguish two enantiomers. But they do differ physically in one somewhat obscure

way: They rotate the plane of plane-polarized light to an equal degree but in

opposite directions. What is plane-polarized light? Light consists of electric

(and magnetic) fields that oscillate in all planes. Certain filters are able to iso-

late light in which the electric field oscillates in only one plane—hence, plane-

polarized light. Rotation of the plane of polarization is called optical activity,

156 CHAPTER 4 Stereochemistry

and molecules causing such a rotation are said to be optically active. The enan-

tiomer that rotates the plane clockwise (as one faces a beam of light passing

through the sample) is called dextrorotatory. The enantiomer that rotates the

plane counterclockwise is called levorotatory.The direction of rotation is indi-

cated by placing a () for dextrorotatory, and a () for levorotatory, before the

name of the enantiomer (Fig. 4.14). Note: There is no connection between (R)

and (S) and the () and () used to denote the direction of rotation of the plane

of plane-polarized light.

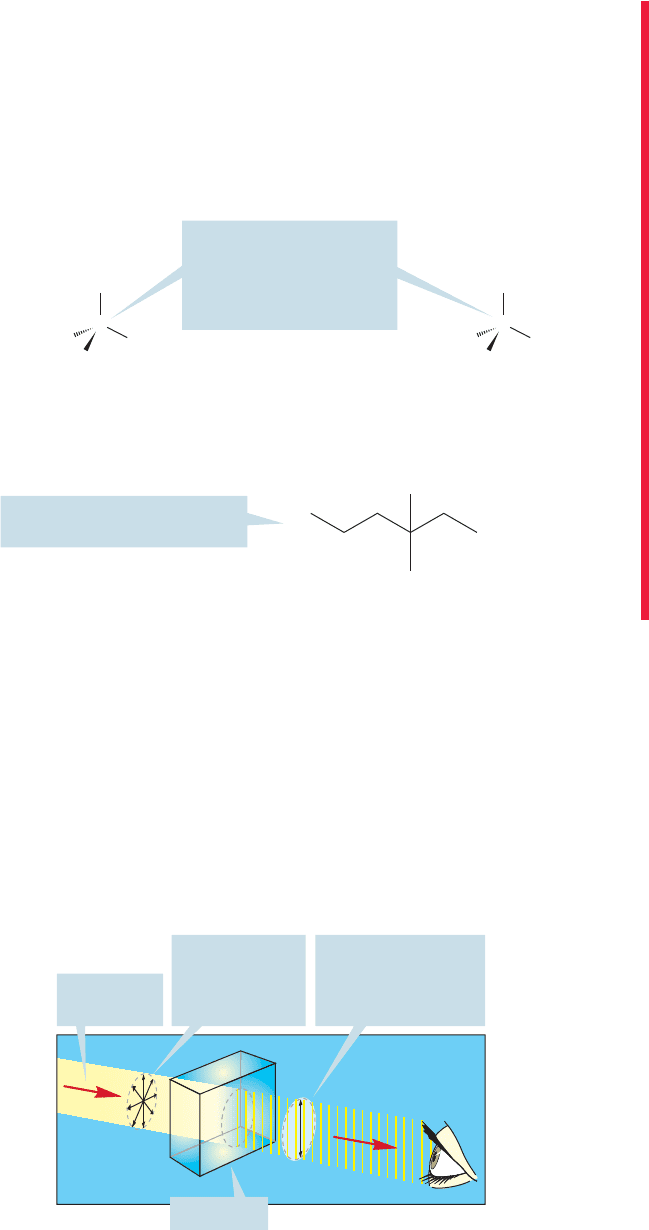

The plane of light is rotated

clockwise as viewed from

the front

Plane-polarized light

enters a tube containing

one enantiometer of

3-methylhexane

Your eye

(+)-3-methylhexane

FIGURE 4.14 The ()-enantiomer

rotates the plane of plane-polarized

light clockwise.The ()-enantiomer

rotates the light an equal amount

counterclockwise.

The plane of light is rotated

counterclockwise as viewed

from the front

The plane of light is rotated

clockwise as viewed from

the front

Racemic, (

+

)-3-methylhexane

–

FIGURE 4.15 There is no net rotation

by a racemic mixture of enantiomers.

One isomer rotates the plane of

plane-polarized light to the right and

the other rotates it an equal amount

to the left.

Very often, equal amounts of the dextrorotatory and levorotatory enantiomers

are present as a mixture. In such a case,no rotation can be observed as there are equal

numbers of molecules rotating the plane in clockwise and counterclockwise direc-

tions,and the effects cancel.Such a mixture is called either a racemate, or a racemic

mixture.The presence of a racemic mixture of enantiomers is often indicated by plac-

ing ( ) before the name as in Figure 4.15.앐

When we are talking about a chiral molecule, how do we know whether the sub-

ject of our discussion is one enantiomer or the racemic mixture? Often the text will

tell you by indicating (), (), or ( ). If no indication is made, we are almost cer-

tainly talking about the racemic mixture. Drawings present other problems. If the

subject is one enantiomer, the drawing will certainly point this out. Sometimes an

asterisk (*) is used to indicate optical activity.

앐

4.5 The Physical Basis of Optical Activity 157

4.5 The Physical Basis of Optical Activity

We have covered the way in which enantiomers differ from each other physically:

They rotate the plane of plane-polarized light in opposite directions. Before we go

on to talk about how enantiomers differ in their chemical reactivity, let’s take a lit-

tle time to say something about the phenomenon of optical activity. How does a col-

lection of atoms (a molecule) interact with a wave phenomenon (light),and how does

the property of chirality (handedness) induce the observed rotation?

Light consists of electromagnetic waves vibrating in all possible directions per-

pendicular to the direction of propagation (Fig. 4.17).

There are times when a three-dimensional representation is important,but the sub-

ject is a racemic mixture of the two enantiomers rather than one enantiomer. Unless

both enantiomers are drawn, the figure appears to focus only on a single enantiomer.

Our molecule, 3-methylhexane, illustrates this point in Figure 4.16. If we are talking

about a racemic mixture of 3-methylhexane but want to show the three-dimensional

structure of this molecule, we should, strictly speaking, draw both of the enantiomers.

In practice this is rarely done, and you must be alert for the problem. Unless optical

activity is specifically indicated, it is usually the racemate that is meant.

H

H

CH

3

C

Indicates the racemic mixture

of the two enantiomers

C

H

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

H

CH

3

C

*

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

This is one enantiomer of

3-methylhexane; to

emphasize chirality, a (+)

[or (–)], or * is sometimes

added to the structure

When it is the racemic mixture that is meant, sometimes

( )

is added. However, this is not always done, and you must be

alert for such times

( )

+

–

+

–

FIGURE 4.16 A variety of conventions is used to indicate the presence

of a single enantiomer.

Propagation

direction

In normal light,

electric field

vectors lie in all

possible planes

In plane-polarized

light, the electric

field vectors all lie

in the same plane

Nicol prism

FIGURE 4.17 A Nicol prism

transmits only plane-polarized light.

CONVENTION ALERT

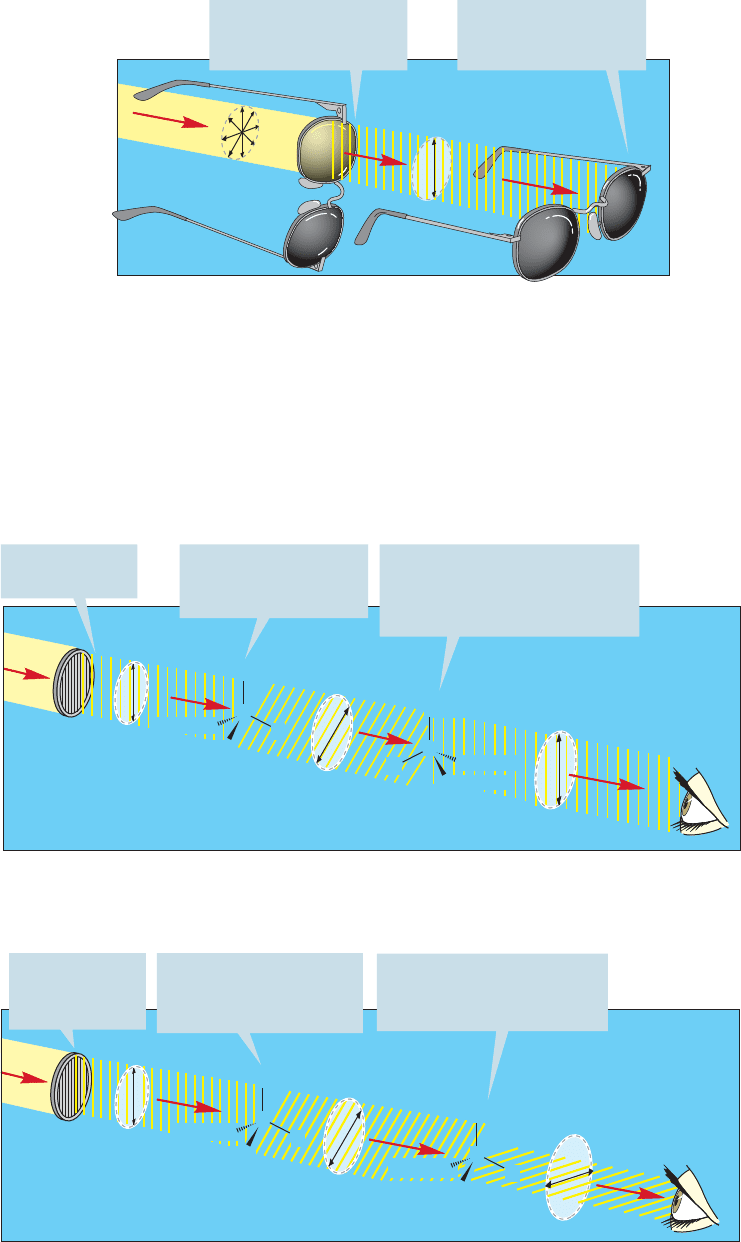

Passing ordinary light through a Nicol prism (or a piece of Polaroid film) eliminates all

waves except those whose electric field vectors are vibrating in a single plane.The clas-

sic experiment to demonstrate this uses two pairs of Polaroid sunglasses. If we observe

light through one pair, we can still see, although the light has been plane polarized.

158 CHAPTER 4 Stereochemistry

The second pair of glasses transmits light only when oriented in the same way as the

first pair. If the second pair is turned 90° to the first pair, none of the plane-polarized

light can pass, and darkness results (Fig. 4.18).

The first pair of Polaroid

sunglasses passes only

plane-polarized light

The second pair,

oriented at 90⬚ to the

first, passes no light

FIGURE 4.18 A classic experiment

using Polaroid sunglasses: The

first pair of sunglasses acts as a

Nicol prism and transmits only

plane-polarized light. If the

second pair is held in the same

orientation, light will still be

transmitted. If it is held at 90° to

the first pair, no light can be

transmitted.

H

CH

3

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

C

H

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

C

Plane-polarized

light

Interaction of the light

with this molecule

rotates the plane

But interaction with a molecule

in this mirror-image position

rotates the plane back—the

net rotation will be 0⬚

FIGURE 4.19 The net rotation

of an achiral molecule

must be 0°.

Now we are ready to see why some molecules are optically active and some are

not.The electrons in a molecule, moving charged particles, generate their own elec-

tric fields, which interact with the electric field of the light. As we have already seen,

many molecules are not highly symmetric, and the interactions of their unsymmet-

ric electric fields with that of the plane-polarized light change the electric field and

rotate the plane of polarization slightly. Achiral molecules,such as 3-methylpentane,

do not give a net rotation of plane-polarized light because equivalent molecules exist

in mirror-image positions, and thus the net rotation must be 0° (Fig. 4.19).

The result is no net rotation of the plane. However, when the interaction is with

a chiral molecule, there are no compensating mirror-image molecules (Fig. 4.20).

H

CH

3

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

C

H

CH

3

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

C

Propagation of

plane-polarized

light

Interaction of the light

with (R)-3-methylhexane

rotates the plane

The solution contains only

(R)-3-methylhexane—so the

plane is further rotated!

FIGURE 4.20 Optically

active molecules, such as

(R)-3-methylhexane, will rotate

the plane of plane-polarized

light.There are no compensating

mirror-image molecules for

this kind of molecule.