Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Dance

200

The estampie was a dance created by the Provençal troubadours during

the 12th century. We know little about its form, and some scholars chal-

lenge the idea that instrumental songs called estampies prove there was a

dance with that name. However, it seems most likely that there was a dance

and that it was not for a line or a ring, but for two people—a knight and

a lady. The steps were probably the same as for the branle, and the musi-

cal units were the same. While the carol’s music could repeat endlessly, the

estampie had a set form, with a beginning and an end. The steps probably

varied with the changes and repetitions of certain musical rhythms or melo-

dies. The two dancers were free to move left or right, or forward or back.

It was a more refi ned version of the folk dance and was performed at court

or in halls for others to watch.

After the Crusade against the Cathars, which destroyed Provençal so-

ciety for a long time, many troubadours fl ed to other regions of Europe:

Italy, Germany, France, and England. The estampie spread and became the

point of origin for later medieval and Renaissance dances. Some versions

of the dance, such as the estampie gai, required the dancers to spring from

foot to foot, not high but very quickly. Dancers stood side by side at times

and at times face to face. They moved side to side and forward and back. It

was a memorized set of fi gures, and dancing it required attention and skill,

not just movement as in the farandole and branle. The sets of steps were

termed simples, doubles, and reprises.

The development of the side fi replace, replacing the central hall hearth,

allowed the hall to play host to both drama and dance during the 14th

century. The shape of the hall, with a central area for dancing, encouraged

dances to evolve into lines or sets of pairs so that dances could move up

and down the hall’s length. When the dancers were in front of the dais,

where the lord sat, they bowed or curtseyed, a custom that continued into

the 19th century. In warmer Italy, houses were organized around a cen-

tral courtyard, and rooms were smaller. Italian dances were usually fi gure

dances within smaller spaces, unless they were outdoors.

During the 14th century, a new dance style developed in Germany. Ger-

mans called it the trotto, and Italians called it the saltarello, but in most

other regions it was called the almain (English) or allemande (French),

which meant a German dance. The dance used the steps of the branle but

with couples in a procession, moving forward. The basic dance fi gure had

each couple step forward with the left, turning slightly, then the right, then

the left, and then hop on the left and raise the right knee. The allemande

may have moved to England following a 1338 visit of King Edward III to

the court of the German emperor, where the English party may have seen

or participated in it.

The almain as recorded in Elizabethan times stated that the couple must

hold hands, facing each other. They step to the left, circling with the dance

Dance

201

steps to change places, and then step to the right, circling back again. Then

the gentleman lets go the lady’s right hand, and they move to stand side by

side, with the center joined hands raised. They move forward with four sets

of the dance steps. Then they join hands and circle again. Couples move

toward the dais of the hall this way.

Dance began to develop into two parallel customs, the peasant folk

dance and the formal court dance. The branle had been both at the same

time, and it continued to be danced in both spheres of society, but its steps

became more complicated. From this time on, dancing masters were em-

ployed to teach young courtiers the steps, since the sets had to be memo-

rized. So many singles, so many doubles, turn and reprise, then doubles

again, and so on. One infl uence may have been the growing complication

and weight of women ’s dresses, which had long trains in the 14th and

By the 15th century, dance fashions required couples to move about the room in a

prescribed way. The music gave them cues for which sets of steps were required.

When each couple reached the high table, where the host was seated, they bowed.

Although choral music used harmony by this time, instrumental music lagged behind.

Dance music was most often produced by just a few instruments; a single instrument,

here the fl ute, carried the melody. (Paul Lacroix, Moeurs, Usage et Costumes au Moyen

Age et a l’Epoque de la Renaissance , 1878)

Dance

202

15th centuries. A ring dance with a hop was diffi cult to execute in such a

dress; ladies had to tuck their trains over their arms. Formal court dances

that focused on movement in processions up and down the room were

more practical. These dances emphasized the correct execution of precise

movements, like a modern line dance.

In the 15th century, the basse dance developed in France. Basse meant

“low,” and scholars are divided as to whether this referred to steps with less

hopping or to a low, peasant origin. It appears to have begun as a country

dance, but it was a formal court dance. Music for the basse is based on a

count of three. Steps were based on the branle and estampie fi gures, but

with more variation. The motions required rising onto toes, stepping for-

ward or back, raising a foot, and sometimes springing slightly into the air.

Steps were grouped into measures, short patterns that combined the mo-

tions and changed with the music.

The dance was planned so that couples stood in a line down the center of

the hall and, as they turned, exchanged places, faced each other, and faced

the front; they gradually progressed to the top of the hall. This action came

to be known in English as a set, and the couples would move to “the top

of the set” and then take their place at the bottom again. In a crowded

room, couples could wait in line to join the set as it moved along.

As Italy’s culture moved from medieval to Renaissance in the 15th cen-

tury, Italian dancers further refi ned the basse. The focus was on small,

graceful motions in which dancers rose on their toes and sank down again

or turned their body in a direction opposite the motion of the foot. The

fi rst was called an aiere, and the second a maniera. Combined, the two mo-

tions formed a movimento, in which dancers rose on their toes, turning

their body and staying in place.

The emphasis in dance was no longer on the rowdy fun of skipping in a

line through the garden, threading the needle while singing a carol in uni-

son. Formal court dances required small orchestras, and in the baroque pe-

riod of the 17th and 18th centuries, many of the greatest composers wrote

dance tunes, including allemandes and basses. Dancing masters taught the

steps and invented new forms. Skill in dancing meant leaping, springing,

turning, and bowing with the gracefulness of a tree bowing in the wind. It

also required perfect execution of the memorized steps and knowledge of

how to interpret cues in the music.

Folk dancing continued to be part of peasant life. Peasants at fairs still

danced farandoles and branles for several centuries. On May Day in En-

gland, peasants wore pieces of greenery on their heads and danced around

a maypole. Paintings of these occasions show a line dance, perhaps in a ring,

with some holding their feet high to stamp down in time to the dance; it is

clearly the branle dance. Music could be as simple as a single piper or fl ute

Dance

203

player, but many folk dances continued to be sung as unison carols. Some

of these old carols persisted as Christmas songs, since round carol danc-

ing was a holiday tradition in many places, including England. “Deck the

Halls” is a Christmas carol that preserves the carol form. The leader sang,

“Deck the halls with boughs of holly,” and the dancers joined in, “Fa la la

la la, la la la la.”

Morris dancing evolved in England out of mumming, a primitive drama

tradition. Mumming often used a sword dance, and a mumming drama

of fi ghting a Moor seems to have developed the motions of the dance. In

Morris dancing, the dancers wear festive costumes and use steps similar to

the ones from the estampie, moving forward and backward. They carry

wooden batons and rhythmically cross these swords with each other in time

to the music.

The idea of dancing was loaded with symbolic meaning after the trauma

of the Black Death plague during 1347–1350. Up to one-third of the pop-

ulation had died, and, 10 years later, a second wave of the plague carried

away many small children. Living had never felt so uncertain, and death

had never felt so random and sudden. The Dance of Death was a common

image in art. Death was shown as a merry skeleton who swept dancers into

a farandole that led them away, unwilling. Nobody got to choose whether

to join Death’s dance; Death seized hands and pulled them into the line.

Post-plague society even acted out this symbol in the strange Dancing

Mania epidemic. Beginning around 1374, townspeople were drawn into

frenetic, nonstop dancing in public. The dance was almost certainly in a

ring, with the steps of a branle. The dancers went around and around, skip-

ping and kicking, until dark and on through the night. They felt unable

to stop, and many gradually died of exhaustion or heart failure. As they

danced, some screamed out that they were seeing visions. At the time, peo-

ple considered it a form of demon possession. The only attempted cure was

to take charge of the hysterical dancing with music and to play the music

calmer and slower until the dancers came to rest.

In the 19th century, Justus Hecker, a German doctor, researched the

phenomenon and tried to solve it as a medical mystery. It is possible the

dancers were suffering from ingesting ergot, a toxic fungus that grows on

rye. Ergot grows more in damp seasons, and the 14th century had unusu-

ally damp weather. The fungus has some hallucinogenic chemicals, includ-

ing lysergic acid. Ergotism causes painful spasms and hallucinations, but it

does not cause dancing. While it is possible ergot toxicity was part of the

problem, making the people less rational, there seems to have been a large

measure of psychological suggestion causing mass hysteria.

See also: Drama, Holidays, Minstrels and Troubadours, Music.

Drama

204

Further Reading

Diehl, Daniel, and Mark Donnelly. Medieval Celebrations. Mechanicsburg, PA:

Stackpole Books, 2001.

Gertsman, E. The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages: Image, Text, Performance.

Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2010.

Hecker, Justus Friedrich Karl. The Dancing Mania and the Black Death. Fairford,

UK: Echo Library, 2006.

Reeves, Compton. Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1998.

Smith, A. William. Fifteenth-Century Dance and Music: Choreographic Descriptions

with Concordances of Variants. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 1995.

Wood, Melusine. Historical Dances: 12th to 19th Century. London: Dance Books,

1982.

Dragons. See Monsters

Drama

Solid information about drama in the early Middle Ages, and outside En-

gland, is diffi cult to fi nd. We know the church sponsored dramas that illus-

trated Bible stories or religious themes for illiterate audiences, but we have

few records of such dramas on the continent until late. The fi rst pageant

recorded in England was acted in 1100. The earliest evidence of plays out-

side England comes from the town of Arras, between France and Flanders.

There seem to be separate European drama traditions, both secular and li-

turgical, that came together to produce the iconic medieval mystery plays.

A few elements seem universal in medieval European drama. Women

never took roles, and both boys and men played the roles of women. Cos-

tumes and staging were important; drama used props, backgrounds, and

even special effects. Drama was often a fund-raising event, raising money

from sponsors and spectators. Most regions only put on one, or at most

two, plays each year because they were so much work. People traveled to a

specifi c place to see its play, which was always held at a certain holiday.

Secular Folk Drama

Pagan culture almost certainly involved some ritual playacting, particu-

larly to celebrate harvest and spring. Some of these traditions can be seen

dimly in folk dramas. These performances seem to have included elaborate

costumes, often with animals’ heads, and the story as enacted often in-

volved a ritual mock execution. It may have begun as an enactment of the

death of the year at winter and its rebirth in spring.

Drama

205

Mummery was traditional in England at the New Year and at Shrovetide’s

Carnival festival. Similar drama and dances also occurred in Germany and

other parts of Europe. The English pantomime horse costume, with one or

two people acting as a horse’s legs, developed from the mummery tradition

in which there also might be actors with stags’ or birds’ heads. There was

no scenery or formal stage; the play took place in a street or hall, with only

the costumed actors and their mock swords or other simple props.

Mumming dramas typically followed a set pattern of story, such as it was.

A presenter began with an explanation of the characters and the action,

and the character of the presenter changed with the season, from Old Man

Winter, to Fool, to Beelzebub the Devil. He called out a champion, usu-

ally Saint George, to fi ght an enemy, usually some kind of Turk or Moor,

a holdover from the Crusades. The champion always won, and the enemy

was killed. Then the mummers brought on a doctor to cure and raise the

dead man. A fi nal dance was performed while the players passed a collec-

tion box among the spectators. This form of mumming led to Morris danc-

ing, a mock swordfi ght dance that has continued among folk dancers into

the present.

Mumming was called a visitation because the mummers arrived from an-

other village or another side of the town in masks and costumes to disguise

their identities. They altered their costumes and play for the time and oc-

casion and did not always act out the ritual execution. In the 14th century,

King Richard II was visited by a group that included popes, cardinals, and

African princes carrying gifts. It was during the Christmas season, so the

mumming imitated the Magi whose Feast of the Epiphany closed the sea-

son. They played mumchance with loaded dice as an excuse to give their

gifts to the king as he won them, and then they performed a dance and

left. Another late medieval Christmas mummery, put on by the goldsmiths’

guild, represented King David and the 12 tribes of Israel and carried the

ark of the covenant. Mummers sometimes invented their own fun, as did

the 15th-century group who dressed as grotesque peasants and presented

marital quarrels to King Henry VI to arbitrate.

The seasons of mumming could be a problem for civic order, since people

drank too much and sometimes acted violent while wearing masks. Some

of the criminal class used mummery as an excuse to commit crimes while in

costume. The church did not approve of mummery, which was clearly not

based in Bible or saints’ stories, and tried to suppress it. Its traditions lived

on, even after the Reformation, in costume balls called masques among the

aristocracy, in the pantomime drama tradition of Christmas, and in Morris

and other folk dances.

Another informal form of drama was the simple pageant. Guilds were

fond of staging pageants for great occasions such as the coronation of a king,

the installation of a new mayor, or any other grand occasion that brought

Drama

206

someone powerful into the city neighborhoods. The simplest form of a pag-

eant was simpler than a full drama. In a pageant, costumed actors on a stage

created a tableau, a scene from something well-known. It could be a Bible

story, a scenario with Roman gods or heroes, or an allegorical scene about

Victory or Virtue. From the stage, the actors addressed short congratula-

tory speeches or songs. While most records of such civic pageants come

from London, other countries in the later Middle Ages staged similar pag-

eants, and they may have been common everywhere.

Another folk drama in late medieval England was the May Day tradition

of acting out stories about Robin Hood and Marian. By the 15th century,

there was a cycle of stories about Robin and his band, including Marian,

Friar Tuck, and Little John. Marian was merged into the mythology of the

May Queen so that it became a strong tradition in the countryside.

Interludes were a late medieval development; they were short plays that

came between stages of grander entertainment. Interludes were often en-

acted by a great household’s servants who had some skill with singing, jug-

gling, dancing, or acting. They could be short plays with a moral or other

forms of entertainment. As a form of entertainment at court, the interlude

outlasted the full-scale miracle or mystery play, and the term came to mean

any sort of stage entertainment of a light sort, especially as comic relief be-

tween weightier matters.

Religious Drama

Religious drama began with stories presented in music and song in

church. At fi rst, stories were presented by being sung in responses between

two choirs or soloists. Then, churches began to use more acting; monks

played the parts of people in the Bible stories, although they stood still in

the choir and merely sang the lines in Latin. By the 10th century, on Eas-

ter morning, monks playing the part of women seeking the tomb of Jesus

entered through a side door. They sang lines to a monk playing the role of

the angel, who answered them. A sepulcher box stood at the front of the

church, by the altar, and the priest could bury a crucifi x in it and resurrect

it on Easter morning. At Christmas, a crib stood at the church’s altar so

monks could act out the arrival of the Magi. As time went on, these dramas

became more realistic, although they continued to use only the melodic

lines of the liturgy, as in opera. Real animals might be included; Francis

of Assisi later staged an outdoor reenactment of the Christmas story, with

a stable and animals, for his town in Italy. The fi rst long musical church

service that crossed into true drama was Adam and Eve, a play about the

temptation and fall into sin of the fi rst man and woman and how one of

their sons murdered the other.

Drama

207

In the 12th century, the productions grew and moved outside into the

churchyard to permit more people to watch. Among other motivations to

move outside the church building was that the priests and monks chose to

stage presentations of Bible stories about wicked people, and they needed

to act out the behavior of the wicked. This was not suited to the Mass, and

it was likely to be noisy and make the people laugh. Another key change was

that since the drama did not need to be part of the offi cial liturgy, it could

be in the vernacular—the language spoken by the people. For the fi rst time,

the offi cial church began to teach directly in the people’s language.

The new drama tradition included both mysteries, meaning Bible stories,

and miracles, meaning stories about the lives of the saints. The longest plays

showed many scenes from the Bible and might portray the entire history

from Creation to the Last Judgment. They might show scenes from the life

of Jesus. Passion plays, fi rst developed in Italy, focused on the death and

resurrection of Jesus.

There are many saints’ plays in French that illustrate miracles after a

saint’s death more than scenes from the saint’s life. These were probably

put on to honor the saint and promote the shrine where the saint’s relics

could be viewed. Many saints’ plays also include lengthy torture scenes and

must have been popular spectacles. The holiest of saints could be killed re-

peatedly, but, due to their holiness, they did not die, so death scenes could

go on and on, with the saints burned, drowned, frozen, and beheaded. The

saints had defi ant, resolute replies to their tormentors. In a society that val-

ued bearbaiting, the torture and death of a saint was good theater. Saints’

plays seem to have been especially dominant in Italy and Spain, where the

cult of venerating saints was even more intense than in Northern Europe.

During the 12th century, the popularity of mystery and miracle plays

grew, and laymen took over producing the plays. Trade guilds often un-

dertook to put on a series of pageants. They often chose a theme related

to their craft. In 1400, the craftsmen of Avignon put on a passion play for

three days at Pentecost. It involved 200 actors and was viewed by around

10,000 people in stands. The town of Arras, on the border of Flanders and

France, staged many large spectacles. Still, most of the remaining evidence

comes from England, where many pageants took place, and we have de-

scriptions, scripts, receipts, and rolls of participants’ names to help form a

clear picture of what went on.

Next to Christmas, the most universally recognized date for staging a

major drama was Corpus Christi Day, a new feast announced in 1264 to

honor the death of Jesus in a general way. The date was dependent on Eas-

ter, so it was a movable feast, but it always fell at the end of May or during

June. The weather was good, and the spring planting was fi nished. Since

the day was not dedicated to any particular saint or Bible story, towns and

Drama

208

guilds could honor it with any religious drama that seemed grand and gen-

eral enough. In June, the hours of daylight were the longest of the year, and

a very long, grand drama could be put on from sunrise to sunset, and even

an hour into the night, if the stage could be lit.

There were two kinds of outdoor productions. One form of staging was

a moving spectacle that snaked through town in a procession of stages on

wagons. These plays were called cycle plays because they were broken into

parts that followed a common theme and told the same history. The other

form, probably less common, was a group of stages, called scaffolds, in a

semicircle. The town that used this type of staging set aside a fi eld for hold-

ing their annual drama and either built permanent scaffolds or kept mov-

able scaffolds in storage, perhaps in guildhalls.

In a moving procession of pageants—a cycle—each guild took on a dif-

ferent pageant’s production. The Corpus Christi cycle of York told the

Biblical history of the world, from Creation to the Last Judgment. Each

guild covered a scene: the creation of the world, the creation of man, the

fall of man into sin, Noah’s ark, Moses receiving the Ten Commandments,

and so on. The fi rst wagon’s drama began at dawn and repeated through

the morning until it reached the end of the route. The last wagon made

its journey through town at the end of the day and reached its last station

after dark. Some stages required trap doors or curtains, and some were two

or even three stories above the wagon. The Last Judgment required hell,

God’s throne, and angels in heaven, so it had a third tall deck high above

the street.

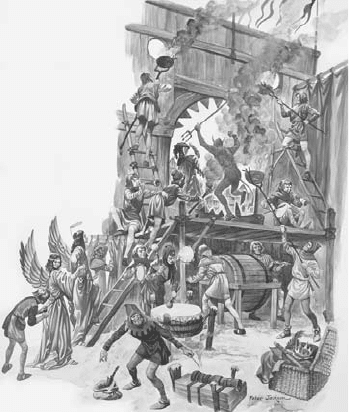

Medieval drama used as many special

effects as possible. When a play was on

a permanent stage rather than a wagon,

much more was possible. Fire and water

effects were very popular. In addition to

showing how fi re and smoke effects

could be handled, the artist has

suggested ways that sound effects could

be achieved with a large drum or a

noisy barrel. Costumes were an

important part of the spectacle.

Costumes were almost never authentic

in the way that modern drama requires;

if the audience understood who the

character was, it didn’t matter if a Bible

fi gure was dressed in a contemporary

way. All women’s roles were played by

men and boys. (Private Collection/©

Look and Learn/ The Bridgeman

Art Library)

Drama

209

The wagons were not standard farm carts but were built for each stage.

The stages may have been square or oblong; some faced to the side, and

others faced to the back so the stage stuck out into the crowd. There was

always a three-sided structure sheltering the stage. It could be the stable of

the nativity story or a desert backdrop with stars. Animals needed for the

action were built of wood, cloth, or wicker and were designed to have one

or two people inside moving them or making them speak. Some stage wag-

ons may have had special effects of water or fi re. As evening came and the

last stages performed the end of the world and the Last Judgment, a dark-

ening street could have been lit by fi reworks or lamps to show the lights of

heaven or hell.

In a stationary outdoor production, there was an open area called the

place and a set of scenes called scaffolds. Medieval productions did not

change the backdrop of the same stage, but rather moved the action to a

different scaffold when the story went from castle to desert. The empty

area—the place—may have been for actions in between the scaffolding, or

it may have been an area for the spectators to stand as they followed the

actors from stage to stage. Scaffolding that was not limited by the size and

stability of a cart could be even more elaborate. Medieval stages, custom

built, included doors, trap doors, ladders, curtains, and upper decks.

Plays were staged indoors toward the end of the Middle Ages. They used

the great hall of a manor house, castle, or guildhall. The great hall always

had a central fi replace, sometimes still in the center of the fl oor rather than

at the side of the room. At the far end of the hall, a raised fl oor held the

lord’s seat and table. This dais was the earliest indoor stage. Indoor plays

most often took place during Christmas, most of all on Twelfth Night, the

close of the season. The other season for plays was Carnival, or Shrovetide

as it was called in England; both seasons were cold enough that indoor

drama was more convenient for all.

Indoor plays took place after dinner or between a meal’s courses. Plays

acted with dialogue and story may not have used much scenery, but a popu-

lar kind of pageant was dependent on elaborate scenery. In this kind, a cur-

tain fell back to reveal a tableau that showed a scene, and it was all about

making it the best spectacle possible through painted scenery, props, and

costumes. A wooden castle, ship, or mountain on wheels would become

the setting for a short scene to be played, sung, or danced by players who

could even be concealed inside the piece.

In all three settings for medieval drama, the acting method sometimes

used the audience as part of the story. There was no clear division of stage

and audience, as in a modern theater, and the lighting was the same in both

places so that the audience did not sit in secluded darkness as in a modern

production. In a street play acted on a wagon, some players would walk

through the crowd and join the play as disciples joining Jesus or devils