Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Compass and Navigation

180

a steady rate of fl ow and had to be fi ne enough not to erode the glass open-

ing it passed through. The glass bulbs had to have the right angle to keep

the sand fl owing evenly. For accuracy, the hourglass was set on a fl at, even

surface. Because a ship at sea is constantly heaving up and down on the

waves, the hourglass was often hung by a cord in a holder that allowed the

hourglass to be easily turned over.

The astrolabe, borrowed from astronomy, became a way to fi nd position

at sea some time during the 13th century, but it is unclear how widely it was

used until the 15th century. The form developed for use at sea became dif-

ferent from the astronomical tool, both simpler and more practical. It had

a heavy brass ring with an alidade for sighting a star or the sun. It was a ring,

not a plate, because when a sailor held it by its top ring, the wind at sea blew

it so it was hard to use; a ring offered less surface for the wind than a plate.

Because it was so diffi cult, it was easier for a ship to use it for determining

the latitude of an island when they were at anchor or on land.

An even simpler instrument came into use in the middle of the 15th cen-

tury. The quadrant became the primary tool for determining a star’s altitude.

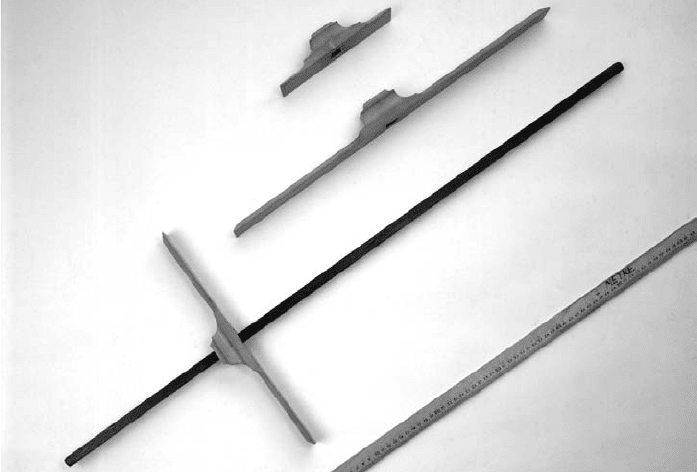

A modern yardstick sits next to a medieval cross-staff with two spare transoms that are

longer and shorter than the one in use. The transom slid along the staff until its top

and bottom were aligned with the horizon and a target star. Markings along the staff

measured how far the transom had slid, and this could be translated into knowledge

of where the ship was on a special map. (SSPL/Getty Images)

Compass and Navigation

181

It had an arc marked off in degrees and an alidade sighting tool along one

side. A plumb bob (a string with a pointed lead weight) hung from the other

side. As one sailor held the quadrant steady, lined up between his eye and the

star, another read the degree where the lead pointer hung.

The cross-staff may have been invented by a Dutch sailor in the 13th cen-

tury. It measured the angle between the horizon and a star, most usefully

the North Star. It was a simple shaft held up to eye level and a moving cross-

bar called the transom. When the bottom of the transom was at the horizon

and the top at the target star, the distance mark along the staff could tell the

viewer’s position with the help of a chart made for the cross-staff.

Soundings, Buoys, and Sea Charts

In ancient and medieval times, sounding was done by dropping a weighted

rope until it touched bottom and then measuring that depth. Soundings

were taken to see whether the ship was about to run onto rocks and also to

help establish the position of the ship. Soundings were usually taken by us-

ing a rope coated with tallow. A big wad of tallow on the end of the rope

could bring up sand or gravel to show what the sea bottom was like and help

the captain estimate the position of the ship.

Sounding was useful in the Baltic Sea, where the water was not very deep

and the coastlines were shallow, but less useful in the much deeper Atlantic

Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. The Baltic region was also an early adopter

of channel markers. Many of the fl at shorelines had few landmarks visible

from a ship, which had to navigate through shallow water and identify the

correct river mouth to enter. There were established sea routes between the

cities in the Hanseatic League; cities established several kinds of markers to

help navigators identify their location.

Archaeologists believe buoys were used as channel markers as early as

1066 on the River Weser. Buoys marked the entrance to the Zuider Zee be-

ginning in 1323, a practice that spread in following years. Early buoys may

have been small, watertight barrels. Sometimes buoys were marked to show

whether a channel was going upstream or downstream. The marker was a

besom, a bundle of twigs attached to a handle, which was placed with its

point upward for one direction, downward for the other.

The Mediterranean Sea had known lighthouses during Greek and Roman

times, but many had fallen into disrepair. In Northern Europe, there was

no early lighthouse tradition except of lighting beacons in bad weather in

some places. The fi rst known European lighthouse was in use in 1202, with

more lighthouses established later in that century. Large wooden beacons

with distinctive topmarks also were placed to identify localities. By 1280,

lighted beacons marked the location of some rivers. Lighthouses also were

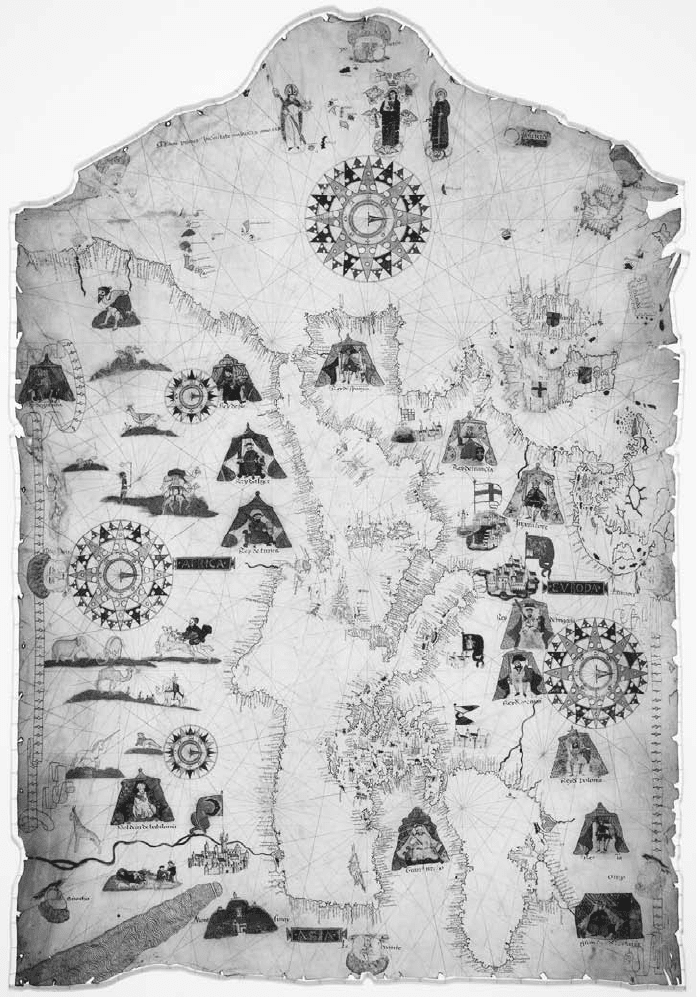

Portolan charts were among the most detailed early maps, because they had the most

practical purpose: fi nding a harbor. Scale did not matter, but capes, rivers, towns, and

other landmarks along the shoreline had to be in correct and detailed order. They

were usually drawn on parchment, which came in large animal-sized sheets and was

very strong even under hard use. (Library of Congress)

Cosmetics

183

established along the shores of the Strait of Dover, the earliest being at

Winchelsea in 1261 and on the Isle of Wight in 1314.

The portolan was essentially a port-fi nding chart or map. For several cen-

turies, Mediterranean seamen wrote down information about ports, tides,

winds, and dangerous coastlines. Gradually, this information was written

into pilot guides (in Greek they were called peripli and in Italian portolani ).

Portolan sea charts were mapped versions of these guides.

A portolan showed highly detailed coastlines marked with ports, sources

of water, and hazards such as reefs or pirates. The names of the ports, capes,

and so on were written at right angles to the coast, on the inland side so as

not to obscure the coastline. There was no attempt to show scale of distances

accurately or to be true to how maps were made, and there was no up or down

to the portolan.

The most distinguishing feature is a network of rhumb lines (lines of a

specifi c geographic direction). These are straight lines for navigation; 16 lines

radiate from a central point. The lines were often color coded for the main

directions (north, south, east, and west) and the intermediate directions

(northeast, southeast, northwest, and southwest). The lines ran through

16 intersecting compass stars, giving a navigator a continuum of straight nav-

igation lines he could use to work his way to the desired port by using his

mariner’s compass for navigating by dead reckoning. Other aids were log

lines to estimate distance and an hourglass for telling time.

See also: Astrolabe, Clocks, Maps, Ships.

Further Reading

Aczel, Amir D. The Riddle of the Compass. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, 2001.

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel. New York:

Harper Collins, 1994.

Launer, Donald. Navigation through the Ages. Dobbs Ferry, NY: Sheridan House,

2009.

Meisel, Tony. To the Sea: Sagas of Survival and Tales of Epic Challenge on the Seven

Seas. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal, 2000.

Woodman, Richard. The History of the Ship: The Comprehensive Story of Seafar-

ing from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press,

2002.

Cosmetics

In the Roman Empire, cosmetics were highly developed, and it is likely

much of this art was preserved in Constantinople, as well as in Italy. The

primitive Franks and Anglo-Saxons made little use of cosmetics, if any,

until they began to imitate the civilized customs of the Byzantine Empire.

Cosmetics

184

Unfortunately, some Roman cosmetics contained high amounts of poison-

ous lead, but it was not known as a poison at the time.

Romans used skin cleansers made of lupin seeds, orris root, and honey, or

they made face packs with eggs and herbs. They routinely had sweat baths

and then had their skin scraped, oiled, shaved, and tweezed. Romans were

heavy users of perfumes made with animal fat and exotic, rich-smelling

ingredients like myrrh, pomegranate, cassia, and cinnamon. We know that

wealthy society in Constantinople continued to make Roman perfumes. Ar-

cheologists have found many beautiful Byzantine jars and pots made of

pottery and glass that almost certainly held perfumes and cosmetics such

as rouge.

Dangerous Roman cosmetics traditions involved changing the color of

the face. Women wanted to exaggerate the whiteness of their skin, as well

as highlight their eyes with black. They could rub chalk into their faces and

outline their eyes with lampblack soot, but more often they used lead. White

lead was a pure white crust that grew on lead when it was exposed to am-

monia, and it formed the basis of white paint, but it was also used to pro-

duce white skin. Eyeliner was more often kohl, made of galena dust, which

is pure lead.

To play up red tones in skin and lips, Roman ladies had relatively harm-

less lip paints and rouges made of red plants in animal fat. After the Roman

army conquered the northern Germanic and British tribes, some Roman

ladies tried to bleach their hair with lye and henna to make it red or blonde

like the northerners’ hair.

In the medieval Islamic countries, as in the Byzantine region, women

used kohl as eye shadow and eyeliner, and they used perfumes a great deal.

They lightened their hair with henna and tweezed or waxed unwanted hair.

Crusaders who visited these countries may have brought back new ideas

about cosmetics.

During the early Middle Ages in Northern Europe before the Crusades,

there is little evidence for cosmetics use, although their red clothing dye,

madder, could have been used to tint lips or cheeks. Most early medieval

texts that discuss a woman’s beauty focus on natural beauty and washing.

The medical book by the legendary Dame Trotula, in the 11th century, rec-

ommended bathing in seawater and using herbs for deodorizing purposes.

Washing was the beginning of beauty, and it was a luxury diffi cult for the

common man to achieve. In addition to cleanliness, beauty was achieved by

braiding hair in elaborate ways and wearing a great deal of gold jewelry.

Good smells were considered healthy, since bad air was one cause of dis-

ease in medieval minds. Perfume, spices, and incense were a matter of health,

not just attraction. Roses and violets were two common scents based on

native fl owers. A number of other herbs were used to scent laundry and

Cosmetics

185

stored clothing, including lavender and balsam (pine needles). The fi rst real

perfumes were made by pressing fl owers into pure lard or almond oil, and

then straining the lard and repeating until it was scented like fl owers. Vio-

lets and roses could be treated this way with success.

In addition to cleanliness and good smells, there is evidence for two strong

folk traditions for female beauty, which then led to cosmetics use. Like Ro-

mans, Europeans had traditionally valued white skin that contrasted sharply

with red lips or cheeks. Folk tales always emphasize the white skin and red

cheeks of the beautiful heroine or princess. As increased travel and trade

brought new ideas into Europe, court ladies began to use simple remedies

to imitate this ideal beauty.

Cosmetics had to be made by the user or her servants, since they were

not sold ready-made until after the close of the Middle Ages. The basic skin-

whitening preparation involved making a white powder and then mixing

it with rose water when needed. One 13th-century recipe called for sprout-

ing wheat in water for two weeks and then grinding it fi nely and straining it

to produce a pure white fl our. Another recipe called for ceruse (white lead)

and herbs to be boiled, strained, and dried for white powder. Lye and fat, the

precursors of soap, could also whiten skin if the lye had not all been neutral-

ized. Rouge could be made of sheep fat, with white or pink tints. Not only

madder but chips of brazilwood, another dye for cloth and paints, could

make a good red tint.

Rose water was the basis for nearly all homemade perfumes and cosmet-

ics. It could be distilled to make its perfume stronger. Other fl owers were

soaked or boiled in water, and these waters were distilled to make more con-

centrated lavender or violet waters. Any time a substance had to be mixed

into water, nothing but a distilled fl ower water would do. Wine was the other

common liquid base. Wine had a mild disinfecting quality, since it was alco-

holic, and it was suitably expensive.

Herbs were both medicine and perfume in medieval cosmetics prepara-

tions. One medieval book recommended boiling rosemary and wine to

make a good skin cleanser, and another book suggested adding fennel and

rose powder. For stubborn blemishes, honey, another suitably expensive in-

gredient, was recommended, boiled with chamomile. Madonna lily root

helped with wrinkles, and rose oil and catmint were thought to remove scars.

Tooth care was not well developed, but white teeth and good breath were

desirable. Strawberry juice was said to help whiten teeth, and, like wine and

honey, it was not easily or cheaply available, so aristocratic ladies could feel

good about the privilege they exercised in using it. One toothpaste recipe

has survived. Its ingredients include several kinds of polishing grit, such as

crushed seashells, pumice, antlers, and cuttle bones. It could not have been

pleasant to use; its other ingredients included alum, nitre, reeds, burnt roots

Cosmetics

186

of an iris, and a fl ower called aristologia. A 13th-century health treatise sug-

gested a more pleasant treatment for bad breath: inhaling roses, mint, and

other herbs as they slowly burned over a small charcoal fi re.

The late Middle Ages brought some distinctive fashions in ladies’ beauty.

Paintings show us fi ne ladies with protruding stomachs as though they are

pregnant, very white skin, and a dramatically receding hairline. Some of the

ladies are clearly Italian, but a high percentage of them are shown with

blonde hair. Cosmetics use and artifi cial appearances had fi nally become

more common in the 15th century. The admired posture and fi gure could be

achieved not only by slumping a bit, but also by using a padded stomacher.

Henna, lye, lemon, and sunshine were bleaching hair blonde, a fashionable

color in Italy. But the key point in women’s beauty seems to have been the

very high forehead. Women wore their hair pulled back tightly and used

tweezers to pluck hairs to make their hairline recede almost to the middle of

their head. Eyebrows were also plucked to be narrow, high, and arched.

Tweezers were not new to the 15th century. There had been many beauty

aids, starting with simple combs, available even to the Vikings. They also had

toothpicks and simple toothbrushes, curling irons, and ear scoops. Since

Roman times, a popular set of utensils came on a ring: tweezers, toothpicks,

and ear scoops. There were also curling irons that had to be heated in a fi re

but could produce artifi cial waves. The rich had small mirrors. They were

highly polished metal at fi rst, but, in the 15th century, some mirrors were

made of glass backed by silver. Mirrors found by archeologists tend to be

Plants were the basis of most cosmetics.

The beautiful Madonna lily was a

common fl ower in home and monastic

gardens, but it could be used to make

an anti-wrinkle potion. Whether it

worked or not, at least it was harmless,

unlike lead-based preparations. (Galina

Samoylovich/Dreamstime.com)

Crusades

187

very decorative compacts made of silver, ivory, or bone; they were real luxu-

ries and status symbols.

The close of the Middle Ages also saw a big step forward in perfumes. Ro-

man perfumes had been based in fat, which can slowly draw the scent out

of fl owers. In the Arabic regions, they had begun using alcohol to distill

fl ower scents. In the 14th century, three alcohol-based perfumes came out

in Europe. The fi rst was called Hungary Water. It was supposedly popular-

ized by Elizabeth, queen of Hungary, in a document claiming she had re-

ceived the idea from a hermit. Into aqua vitae (alcohol distilled from beer

to a higher concentration) went rosemary and sometimes other fl owers

such as lavender. Eau de Chypre was a more exotic import from the Medi-

terranean region; its ingredients were not native to Northern Europe. Tra-

gacanth (a dried sap of the Astralagus legume native to the Middle East),

styrax (a tropical shrub), calamus (a water plant native to India), and labda-

num (a resin from a Mediterranean shrub) must have produced a truly ex-

otic smell for European royalty. Less exotic Carmelite Water distilled lemon

balm and lemon peel in alcohol with nutmeg, cloves, coriander, angelica

root, and elderfl ower. Lemon could only come from the citrus-growing

Mediterranean region.

See also: Hair, Hygiene.

Further Reading

Freeman, Margaret B. Herbs for the Medieval Household. New York: Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 1997.

Pointer, Sally. The Artifi ce of Beauty. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2005.

Woolgar, C. M. The Senses in Late Medieval England. New Haven, CT: Yale Uni-

versity Press, 2006.

Copper. See Lead and Copper

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religiously motivated wars that began in

the 11th century and ended in the 14th. Most of the Crusades were wars

against Muslim strongholds and rulers in Egypt, Syria, and Palestine, but

some Crusades were staged within Europe. The original motivation for the

First Crusade was to push back Muslim Turkish control of Jerusalem and

create safe roads for European pilgrims. Constantinople had been at war

with fi rst the Arabic Muslims and then the new Turkish invaders, but they

were not as successful in land battles as at sea. Turkish conquest and brutal-

ity prompted the Byzantine emperor Alexis Comnenus to write a letter to

Pope Urban II asking for military assistance. The Pope’s call to European

Crusades

188

knights, given in a speech at Clermont, France, launched the First Crusade

in 1095.

European trade with the East increased dramatically during and after the

Crusades. The Muslim conquest of Byzantine territory in Palestine and

Egypt had blocked most European trade with these places for several centu-

ries. By establishing a European kingdom in Palestine, the Crusaders re-

connected Europe with the regions around Constantinople. Trade in spices

and cloth was infl uenced fi rst as Asian spices, silk, and cotton came to Italy

and then to the rest of Europe. New ideas in clothing fashions, food, and

manners also came through the Crusaders to Europe.

Holy Land Crusades

In the four centuries following the Arab conquest of Jerusalem in 638,

the city had changed its policy toward Christian pilgrims several times.

Charlemagne negotiated a deal with Caliph Harun al-Rashid to maintain a

hostelry for Roman Catholic pilgrims in Jerusalem. In the eighth and ninth

centuries, under Fatimid rule, there were periodic massacres of pilgrims and

Byzantine monks who lived in Palestine. In 1009, Caliph al-Hakim of Egypt

ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the cave-

tomb under it. The Byzantine emperor arranged for some reconstruction

later in that century, but it remained largely in ruins. The Seljuk Turks in-

vaded the region and seized Jerusalem around 1073; they massacred the

inhabitants of nearby cities. Bandits contributed to making the roads in

Palestine very unsafe.

The First Crusade began in 1095 with an appeal by Pope Urban II to the

assembled bishops and knights of Western Europe. He called on them to

cease fi ghting with each other, unite, and save the Holy Land for Christians.

He promised that those who joined the war for the Cross would have their

sins forgiven. The Crusaders were primarily drawn from the warlike Franks

and Normans, who lived in France, Germany, Sicily, and England.

The promise to go and fi ght for the Holy Land was called “taking the

Cross.” Those who had vowed not to stop until they had reached Jerusalem

and struck their blow were permitted to wear a cloth cross prominently on

their clothing. Crusaders made cross banners and painted crosses on their

shields. At the time of the First Crusade, the word crusade had not been

coined. The knights referred to themselves as pilgrims. In later Crusades,

the Latin word crucesignatus meant “one signed with the Cross.” The last

form of the word, which became the modern word crusade, was French

croisade, “the way of the Cross.”

The fi rst wave of Crusaders was composed of mostly Norman knights

from England, France, and Sicily. The count of Boulogne, the duke of

Lorraine, the duke of Normandy, the count of Toulouse, the viscount of

Crusades

189

Bourges, the count of Flanders, and many other landowning knights of the

middle-rank aristocracy took the Cross.

A peasants’ army also tried to join the Crusade and set off behind Peter

the Hermit through Germany and Hungary. They were not successful in

reaching their destination. Another small group under a German count mas-

sacred Jewish communities and were, in turn, defeated before they neared

the Holy Land. But the main body of Norman knights reached Palestine.

They captured the main cities of Antioch, Tripoli, Acre, and fi nally Jeru-

salem in 1099. They set up the Crusader kingdoms in the region they called

Outremer, which meant “over the sea.” The prince of Antioch, the count of

Edessa, the count of Tripoli, and the king of Jerusalem were all created from

among the Frankish lords.

The Crusader kingdoms sustained the Frankish nobility for 90 years, un-

til 1189. At that time, a dynamic Arab general known as Saladin successfully

defeated the king of Jerusalem and his Frankish allies. He reentered Jerusa-

lem and quickly seized the remaining cities of the Palestine coast.

The Second Crusade, led by King Louis of France, had come and gone in

1148 and had ended with a defeat at Damascus. The Third Crusade began

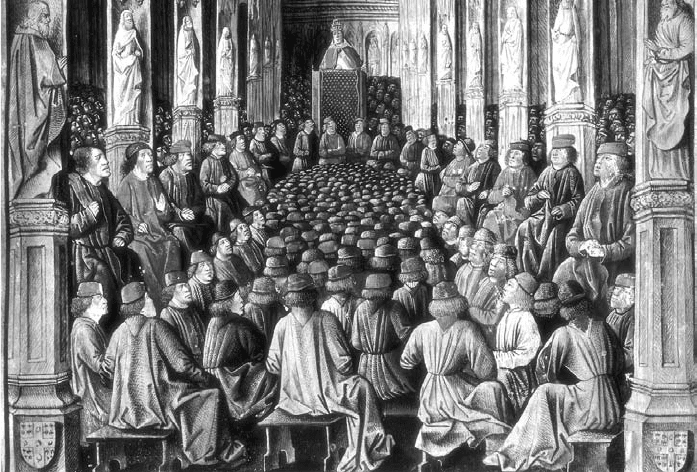

In the 15th century, an artist looked back on the historic Council of Clermont where

Pope Urban II fi rst called for a mass defense of the Holy Land. The artist shows the

churchmen in robes and hats of the 15th century and has placed them in a Gothic

hall with tall windows. The occasion was recalled with pride and nostalgia, since

medieval people had no doubt about the rightness of the Crusades. (Jupiterimages)