Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Embroidery

220

a table or propped up like an easel. The fabric was often pulled tight by

cords that ran through the edges and around the frame, so it was not eas-

ily removed.

Quilting comes into the record only as a technique for making padded

clothing. Quilted coats and tunics, for winter or to wear under armor,

had long been made all over Europe. Quilting was a plain, undecorated

technique to make thick material, rather than a decorative craft. Quilted

hangings or blankets, with decorative stitching, were not common until

after 1500.

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry is the most famous example of early medieval em-

broidery. It is not a proper tapestry because the pictures are not woven. It

is a wall hanging, but for that reason it has become known as a tapestry.

The Bayeux Tapestry belonged to the Cathedral of Bayeux, a city in

Normandy. It was probably embroidered in England in the years immedi-

ately following the Norman conquest of England. The most likely patron

is the bishop of Bayeux, the duke’s half-brother Odo. It is a very long strip

of linen with an embroidered mural showing the events leading up to the

Battle of Hastings and featuring Odo as the duke’s adviser at several points.

The Bayeux Tapestry uses wool embroidery to explain the Normans’ justifi cation for

invading England in 1066. (ImagesEurope/StockphotoPro)

Eyeglasses

221

It is shorter than it originally was, but its current length is still just over 210

feet. It is less than 3 feet high. It probably hung at eye level in the bishop’s

feast hall and was later taken into the cathedral for safekeeping. Violence

during the French Revolution nearly destroyed it, and it sustained damage,

but conservators have been able to preserve it.

The embroidery is in woolen thread using only eight basic colors dyed

in vegetable dyes. Most spaces are fi lled with couched threads. The effect

is very regular, with the long supporting threads forming a neat row-like

look. Details, such as lettering, lances, ropes, and the cross-hatching of chain-

mail, are in stem stitch. People and their garments are outlined in a con-

trasting color, but not always in black.

The main subject of the Bayeux Tapestry is the long story of why and

how the duke of Normandy invaded England in 1066. The events leading

up to the invasion, including a moment when the future king of England

swore fealty to the duke while in Normandy, are shown in scenes along the

panel, with narration above, “Here Harold took an oath to Duke William.”

The scenes go on to show the shipbuilding, the loading of equipment, the

crossing of the Channel in open boats fi lled with horses, the building of

forts, and the eventual battle. While the scenes do not always have realis-

tic perspective and detail, at times they show details of daily life. The Nor-

mans are shown cooking outside before the battle and using their shields

as tables.

The top and bottom margins illustrate fables or show strings of mythical

or unusual animals and birds. At times the main scenes use the margins as

extra space for ships’ masts or dying warriors. There is rarely any narrative

connection between the marginal illustrations and the mural’s story, mak-

ing it a very unusual choice in the plan of the wall hanging.

See also: Cloth, Shoes, Tapestry.

Further Reading

Coatsworth, Elizabeth. “Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon

Embroidery.” Medieval Clothing and Textiles, vol. 1, ed. Robin Netherton and

Gale R. Owen-Crocker. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2005.

Musset, Lucien. The Bayeux Tapestry. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2005.

Staniland, Kay. Embroiderers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Wilson, David M. The Bayeux Tapestry. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Eyeglasses

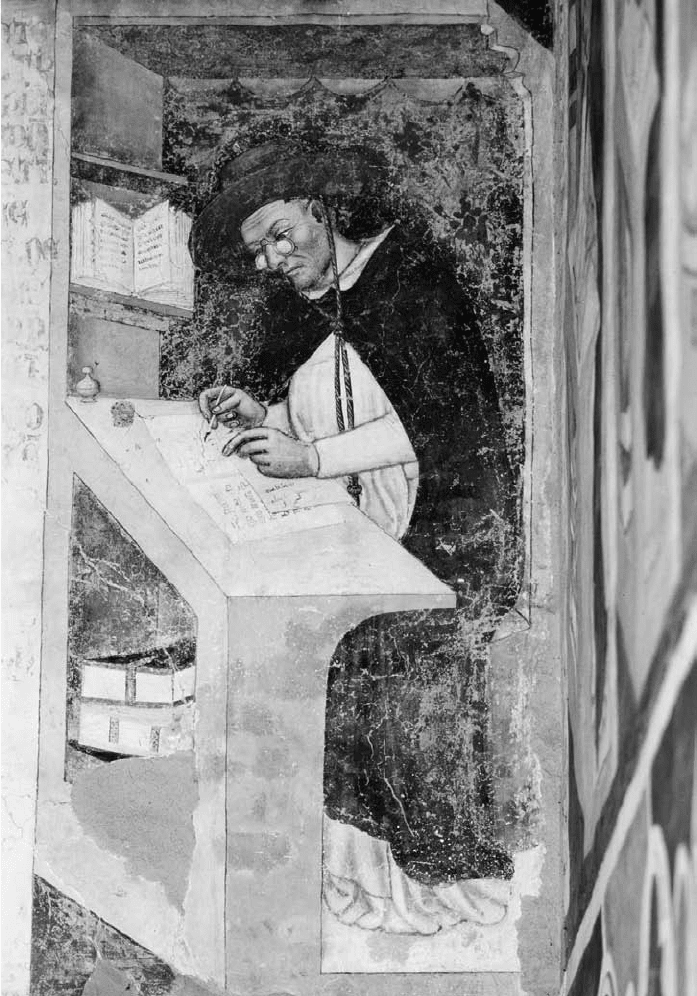

Medieval paintings began to show simple eyeglasses during the 14th cen-

tury. Although the invention of vision aids began the chain of inventions

that led to telescopes and microscopes, not many people owned or used

Medieval eyeglasses were placed in simple, minimal frames without supports over the

wearer’s ears. They were not only uncomfortable to wear but also too expensive for

all but serious scholars or other professionals who needed to read account books and

see small details. Even so, to medieval people, such technology was next to a miracle.

(San Nicolo, Treviso, Italy/ The Bridgeman Art Library)

Eyeglasses

223

glasses. In medieval Europe, wearing glasses had a negative connotation in

society. The only people who really needed to see so well were monks who

copied books, merchants and their bookkeepers, and scholars. Medieval

society admired, rather, knights and men of action, who had no need of

lenses or pens.

Nobody knows for sure who invented the fi rst eyeglasses. We know the

invention took place around 1300, and it was either in Italy or in England.

Roger Bacon wrote a lengthy treatise on his scientifi c studies at the Pope’s

request. Opus Majus, sent to the Pope in 1267, included a treatise on op-

tics, probably based on Arabic treatises he had been reading in Latin. He

described all the principles of the eye and of lenses and may have invented

eyeglasses. On the other hand, in 1306, an Italian priest spoke in a sermon

of how eyeglasses were one of the great wonders of the age and that they

had been invented in Italy about 20 years before. Many traditional accounts

gave the credit to a Dominican monk named Allesandro della Spina, who

died in 1313.

Paintings dating from around 1350 depict monks and saints wearing

eyeglasses or using magnifying glasses for their manuscripts. These early

eyeglasses did not have a frame to support them using the nose and ears.

There were two lenses in a frame, often hinged, and it only stayed on by

clamping it on the bridge of the nose. The wearer often had to hold the

hinged lenses in the right place with a free hand. Eyeglass frames that held

the glasses to the face came later, during the 16th century.

A frame for eyeglasses was discovered in a London excavation dating to

the 15th century. The frame is made of bone and is in two pieces. At the

hinge point, they are riveted. It is possible that the two lenses could be

aligned so that together they would act as a more powerful magnifying

glass.

Further Reading

Frugoni, Chiara. Books, Banks, Buttons, and Other Inventions from the Middle Ages.

New York: Columbia University Press, 2003

Gordon, Benjamin L. Medieval and Renaissance Medicine. New York: Philosophi-

cal Library, 1959.

Rosenthal, J. William. Spectacles and Other Vision Aids: A History and Guide to Col-

lecting. Novato, CA: Norman Publishing, 1994.

F F

Fairs

227

Fairs

A fair was different from a town market. The market was a local, frequent

event; it took place in a town center, often under a cross erected by the

local church. The fair was an infrequent event; it was held once a year for a

limited time, though some towns had more than one fair during the year.

Some vendors made a living traveling from fair to fair, selling animals or

wares they had made. Fairs were particularly important in outlying regions

where traders did not often come. In Scandinavia, fairs were always in the

summer, when travel was possible.

Traders from as far away as the Mediterranean Sea made regular stops

at the large northern fairs to buy furs. In these far-off regions, towns that

hosted even an annual fair became the business hubs that grew into cities.

International trade at fairs brought many foreign words into the host lan-

guages, even in the Middle Ages. Arab traders gave Arabic words to Italian

merchants, whose contact with the large northern fairs brought words like

orange, bazaar, and sugar into French and English.

Since large animals took time to grow, many local farmers waited for the

nearest annual fair and took their horses, cows, or sheep there. Vendors

could be local or from far away, even from overseas. Fairs drew entertainers

and gypsies as well as thieves. Fairs meant large meadows fi lled with animals

brought from far away and the town square fenced off with animal pens.

Fairs were not always held at towns. They were often held at crossroads

where two main highways met. The fair’s sponsor had to own the land and

might put up temporary buildings.

A charter to hold a fair meant the sponsor had the right to collect fees

from participants. Tollbooths outlined the fair grounds, and porters col-

lected fees. The charter to hold a fair could be very lucrative, and it cost the

king nothing to grant. It was a favored way of rewarding knights who had

fought in the king’s service, since it gave them income for life without the

king having to pay it. Charters for fairs could be given to towns or to the

owners of even small manors. Churches and monasteries also had charters

for fairs.

Holding a fair also meant keeping order at the crowded event. The chief

offi cial with authority to make appointments and rules for the fair was called

the Keeper of the Fair. In England, the charter included the right to hold

a court of justice at the fair. The fair courts were fi rst named pied poudre in

medieval French, meaning “dusty feet.” As English became the dominant

language again, the name became piepowder, and the fair courts were called

Piepowder Courts. A Piepowder Court dispensed instant justice for the few

days the fair was in session. Any commercial disputes went immediately to

the court. Unfair sales practices, pickpocketing, contract disputes, and dis-

ruptive behavior could all be tried almost instantly at the court. The court

Fairs

228

could not jail or execute, but it had the power to put people in the public

stocks and level fi nes. The charter gave the Piepowder Court full rights and

a promise that other civil authorities would not interfere.

Each fair was traditionally held on the same day of the year, denoted by

the saint honored on that day. Some towns held a fair to honor their patron

saint. Some places had more than one fair in the year, and each fair benefi ted

a different sponsor. Medieval Bath held four fairs; one benefi ted the king,

one the bishop, one the convent, and the fourth benefi ted the town itself.

Each town had its own regional measurements. The keeper of the fair

had a set of metal weights and rulers, and an offi cial made sure the weights

and rulers used by merchants matched the standard for that fair.

English Fairs

England’s oldest fair, begun in Anglo-Saxon times, was Saint Giles Hill;

its largest fair during medieval times may have been Stourbridge Fair. Some

fairs grew so large that they dominated the nearby town and became a new

town center. Saint Ives fair became the town of Saint Ives. Fairs proliferated

during the 13th-century reign of Henry III, a king whose generosity grad-

ually impoverished him. During the 13th and 14th centuries, about 5,000

fair charters were granted in England and Wales. Many began to special-

ize in one kind of trade. Tavistock held a large goose fair, and Horncastle

had a horse fair. The priory of Horsham Saint Faith’s held a sheep fair that

later became the largest cattle fair in England. These specialty fairs mostly

followed the patterns of the animals’ seasons and the seasonal needs of cus-

tomers. Goose fairs were most often held around Michaelmas, at the end of

September, in preparation for the holiday feasts coming up.

Although fairs specialized, any kinds of goods could be bought at a re-

gional fair. Chapmen and the representatives of international merchants

sold raw materials: tin, iron, brass, lead, amber, wool, furs, wine, spices,

and animals. The largest fairs attracted the fi nest international goods, while

the smaller rural fairs had mostly domestic goods sold by traveling salesmen

known as chapmen. They also sold manufactured goods: glassware, pot-

tery, tools, knives, cloth, toys, and jewelry. The goods traveled on land by

pack train—strings of mules and horses carrying things in sacks. Many me-

dieval roads were not good enough to handle large wagons.

Early medieval fairs lasted three days: the saint’s day and the days before

and after it. Fair charters were extended over time, and some fairs began

to go on as long as two weeks by the 13th century. Visitors to the fair,

whether selling or buying, had to fi nd a place to live. Inns were full, and

some farmers rented places in their barns. The poor slept outdoors. Some

vendors traveled with wagons they could sleep in. Large fairgrounds that

had frequent fairs built permanent booths with small sleeping quarters for

Fairs

229

rent. Peasants could advertise willingness to stable animals by posting a

small bunch of hay over the barn door. They could advertise home-brewed

ale with a branch posted above the house door.

Fairs began with criers who announced the coming event. Vendors were

gathering with their herds. The parish church began the fair with a Mass,

and the mayor and town offi cials paraded to open the fair in their best

robes. In earliest times, a glove was hoisted onto a pole as a banner—the

symbol of the manor’s power in force at the event. Later fairs used a ring-

ing bell to open the fair. The town offi cials handed offi cial jurisdiction of

the fair to the Keeper of the Fair and his clerk, the offi cial in charge of re-

cords, and made welcome speeches. They appointed bailiffs and porters to

collect tolls for the fair; there were tariffs on all merchandise that passed

the tollbooth. The clerk of the fair visited the vendors and examined their

wares to be sure everything was in order. A large fair had notaries on hand

to certify transaction receipts. Buyers had to present proofs of purchase to

the porters as they left.

Entertainers traveled to fairs and put on shows after the sun had set and

trade stopped for the day. Medieval traveling entertainers included min-

strels and jongleurs of many kinds. Some sang, and some juggled or did

other tricks. Some traveled with trained animals, such as monkeys or dogs.

Many fairs also attracted athletic contests. In England, archery contests

were popular. In the late Middle Ages, knights might hold a tournament

for the spectators. There were animal sports, such as bearbaiting and cock-

fi ghting. Horse-trading fairs had races.

French Fairs

Fairs had a very ancient history in the land of the Franks. The fair at

Troyes may have begun in pre-Christian times. The fi rst fair at Saint Denis

was held in 629 by grant of the Merovingian king Dagobert to collect taxes

on the sales. The count of Paris was to collect these taxes for the king, and

the grants were reaffi rmed by kings into the time of Charlemagne and be-

yond. The Saint Denis Fair ran during the month of October. It was an in-

ternational event from the start; merchants from Spain and Italy attended.

During the 10th century, Flanders became a weaving center, and the counts

of Flanders founded fairs to promote the cloth trade.

The most famous group of fairs took place in Champagne and was domi-

nated by the Flemish cloth trade. The region of Champagne was midway

between Flanders and Italy, and its towns were situated on a network of riv-

ers that made travel easier. The counts of Champagne developed the region

to make it more hospitable to trade. They drained swamps and built canals

connecting the rivers. Champagne’s fairs directly benefi ted the count, who

hired inspectors, security guards, clerks, notaries, couriers, laborers, and