Jan Lindhe. Clinical Periodontology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ORTHODONTICS AND PERIODONTICS • 755

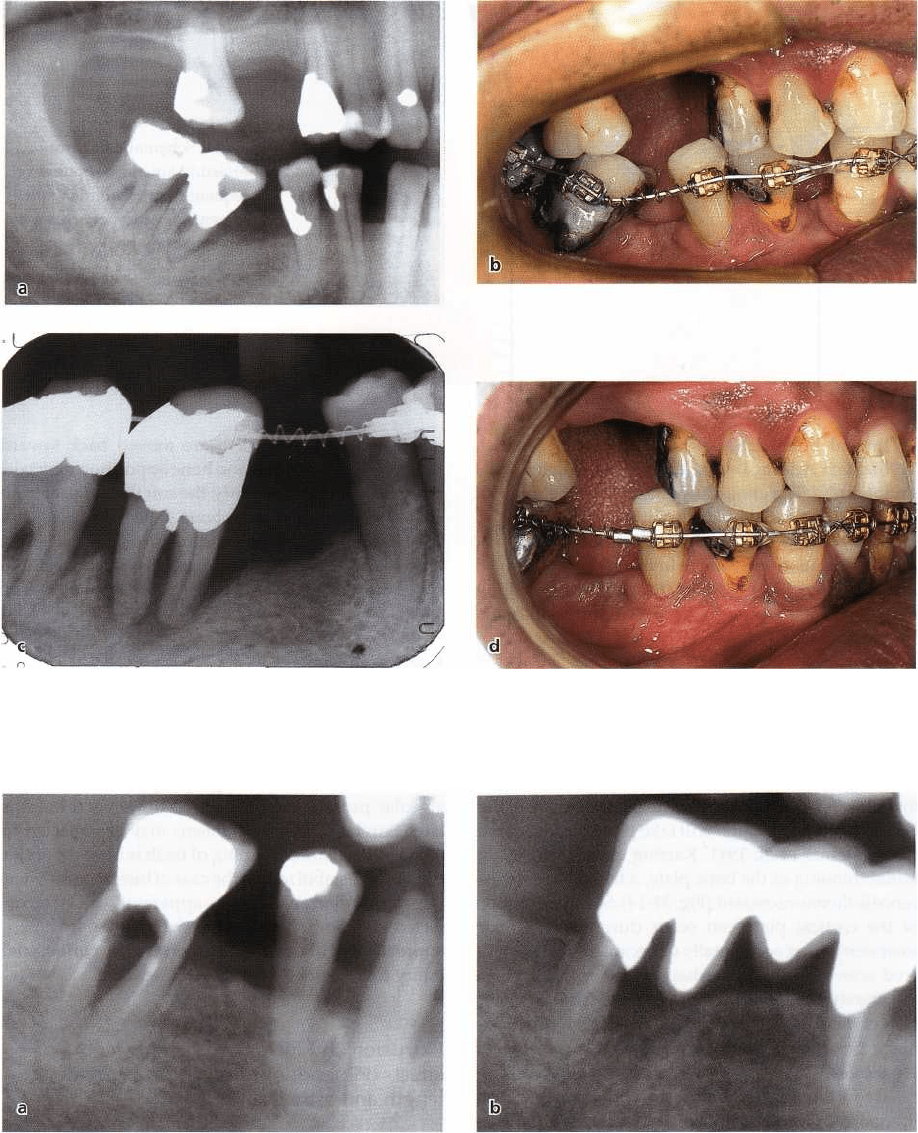

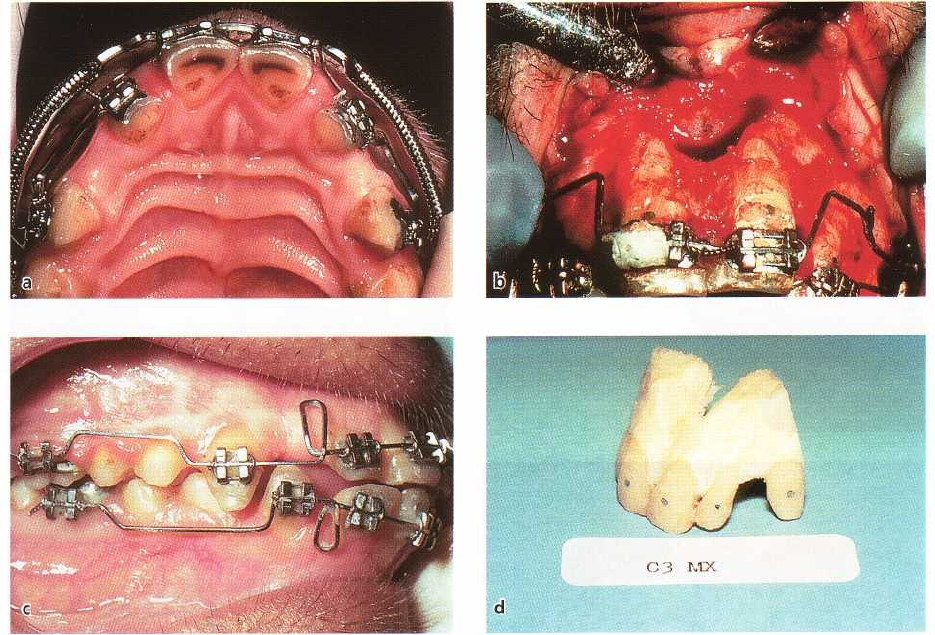

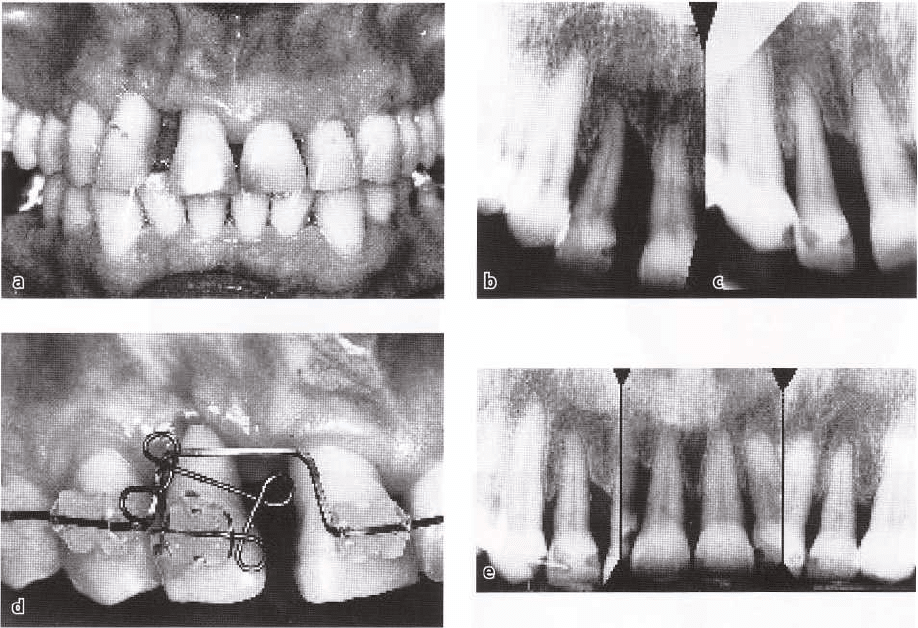

Fig. 31-9. "Hopeless" mandibular right first molar (a) can be used as part of anchorage to move the premolars

mesially and upright the second molar (b-d). The first molar may be kept, or extracted, after the orthodontic treat

ment period.

Fig. 31-10. "Hopeless" mandibular right first molar (a) was used as anchorage during orthodontic treatment to

close spaces anteriorly, before it was hemisectioned and the distal root employed as a bridge abutment (b).

Histologic observations in animal experiments have

confirmed that when light forces were applied to

move

teeth bodily into an area with reduced bone

height, a

thin bone plate was recreated ahead of the

moving

tooth (Fig. 31-13) (Lindskog-Stokland et al.

1993). The

key to moving teeth with bone is direct

resorption in

the direction of tooth movement, and

avoiding

hyalinization. Teeth can be moved with bone

into the

maxillary sinus also (Melsen 1991).

Conclusion

Although the results of clinical experiments and fol-

low-ups are encouraging, provided light forces are

used and excellent oral hygiene is maintained, it is

probably wise not to stretch the indications for tooth

movement into constricted bone areas too far. Marked

gingival invaginations are sometimes seen in such

areas (Fig. 31-12), and computer tomography analysis

and human histological findings indicate that buccal

756 • CHAPTER 31

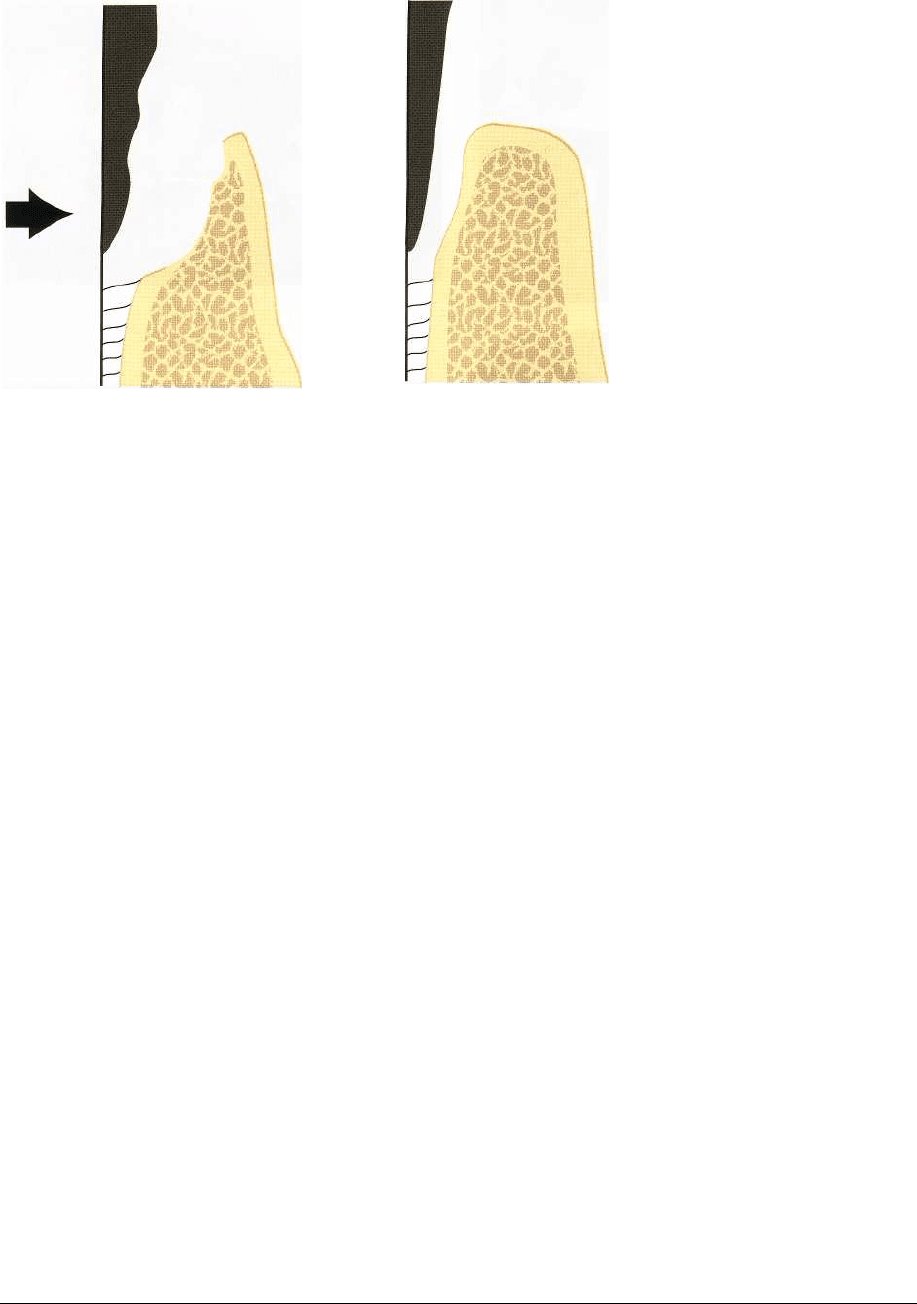

Fig. 31-11. Schematic illustration

of persisting junctional epithelium

subsequent to orthodontic tooth

movement (direction of arrow)

into an infrabony pocket.

or lingual bone dehiscences may occur (Diedrich

1996). Such defects are not revealed by conventional

radiography. The clinical significance of the gingival

clefts and bone dehiscences with regard to relapse

tendency and periodontal status is not known. For

orthodontic tooth movement into markedly atrophied

alveolar ridges, the possibility to acquire new bone by,

for example, GBR procedures (see Chapter 38) should

be considered.

Tooth movement through cortical bone

Experimental studies in animals have demonstrated

that when a tooth is moved bodily in a labial direction

towards and through the cortical plate of the alveolar

bone, no bone formation will take place in front of the

tooth (Steiner et al. 1981, Karring et al. 1982). After

initial thinning of the bone plate, a labial bone dehis-

cence is therefore created (Fig. 31-14). Such perforation

of the cortical plate can occur during orthodontic

treatment either accidentally or because it was consid

-

ered unavoidable. It may happen for example (1) in

the mandibular anterior region due to frontal expan-

sion of incisors (Wehrbein et al. 1994), (2) in the max-

illary posterior region during lateral expansion of

cross-bites (Greenbaum & Zachrisson 1982), (3) lin-

gually in the maxilla associated with retraction and

lingual root torque of maxillary incisors in patients

with large overjets (Ten Hoeve & Mulie 1976), and (4)

by pronounced traumatic jiggling of teeth (Nyman et

al. 1982).The soft tissue reactions accompanying such

tooth movements are discussed later in this chapter

and in Chapter 30.

Interestingly, however, there is potential for repair

when malpositioned teeth are moved back toward

their original positions, and bone apposition may take

place (Fig. 31-14). Evidently, the soft tissue facial to an

orthodontically produced bone dehiscence may con-

tain soft tissue components (vital osteogenic cells)

with a capacity for forming bone following reposition-

ing of the tooth into the alveolar process (Nyman et al.

1982).

Conclusion

The clinical implication of these observations is en-

couraging. Bone dehiscences which may occur due to

uncontrolled expansion of teeth through the cortical

plate may be repaired when the teeth are brought

back, or relapse, towards a proper position within the

alveolar process, even if this occurs several months

later. Similar repair mechanisms may be expected to

occur when marked jiggling of teeth is brought under

control and stabilized. In the case of buccal cross-bites,

the initial discrepancy can apparently be overcor-

rected with both slow and rapid expansion treatment

approaches without causing permanent periodontal

injury to the settled occlusion.

Extrusion and intrusion of single teeth -

effects on periodontium, clinical crown

length and esthetics

Extrusion

Orthodontic extrusion of teeth, or so-called "forced

eruption", may be indicated for (1) shallowing out

intraosseous defects and (2) for increasing clinical

crown length of single teeth. The forced eruption tech

-

nique was originally described by Ingber (1974) for

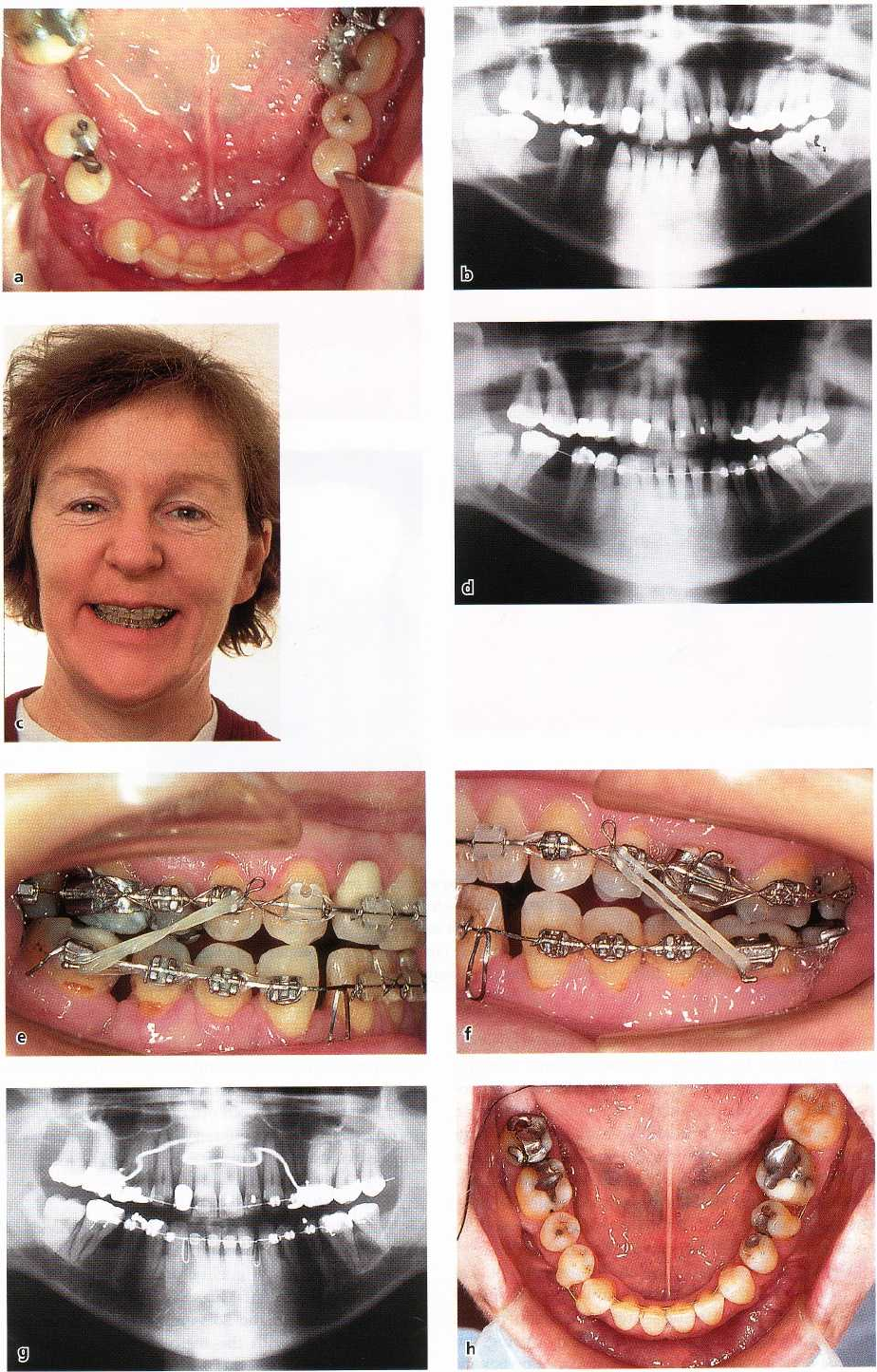

Fig. 31-12. Orthodontic tooth movements into edentulous areas with reduced bone height in compromised mandi

-

ble of adult female patient. During the orthodontic treatment (c-g), the teeth were moved to close three areas of

marked alveolar bone constriction (a,b), most notably in the right first molar area. Note that the impacted third mo

-

lar erupted spontaneously as the second molar was moved mesially (g). (h) shows final result with bonded six-unit

lingual and two-unit labial retainers.

ORTHODONTICS AND PERIODONTICS • 757

758 •

CHAPTER

31

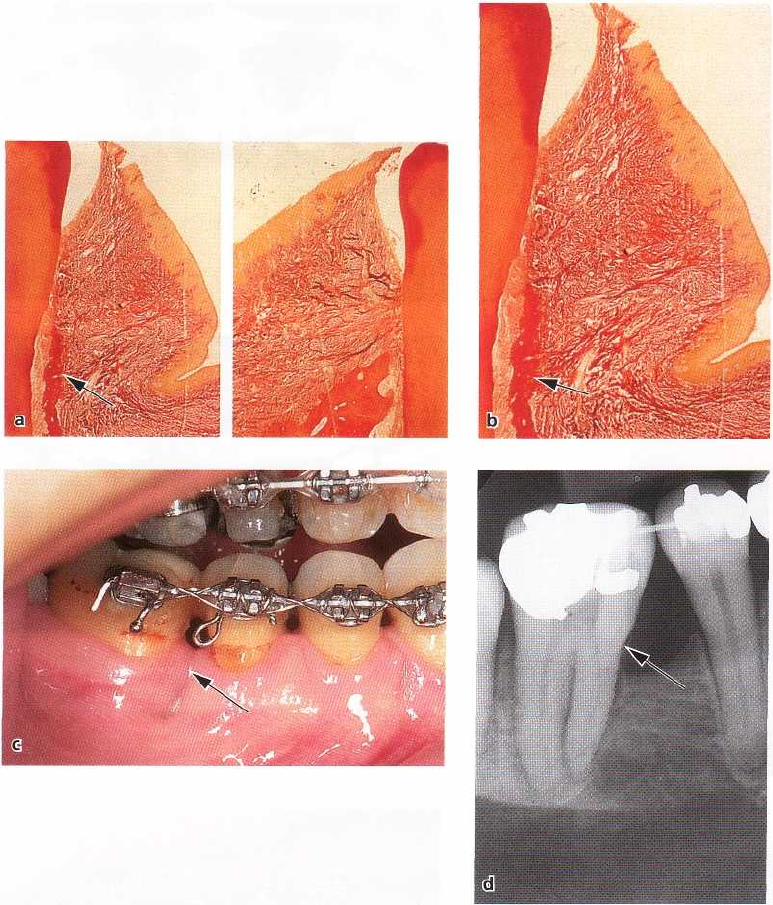

Fig.

31-13.

(a) and (b) show histologic specimens from experimental orthodontic tooth movement into edentulous

areas in dogs. The thin bone spicule along the pressure side of the test tooth (b) indicates tooth movement with,

and not through, bone. (c) and (d) show the same patient as in Fig.

31-12.

Note radiographic visualization of the

thin bone spicule on the mesial side of the second molar (arrow in d). Although the molar is moved to contact the

second premolar, a marked gingival invagination is present in the area (arrow in c). (a) and (b) from Lindskog-Stok

land et al.

(1993).

treatment of one-wall and two-wall bony pockets that

were difficult to handle by conventional therapy

alone. The extrusive tooth movement leads to a coro-

nal positioning of intact connective tissue attachment,

and the bony defect is shallowed out. This was con-

firmed in animal experiments (van Venroy & Yukna

1985)

and clinical trials. Because of the orthodontic

extrusion, the tooth will be in supraocclusion. Hence,

the crown of the tooth will need to be shortened, in

some cases followed by endodontic treatment.

During the elimination of an intraosseous pocket

by means of orthodontic extrusion, the relationship

between the CEJ and the bone crest is maintained. This

means that the bone follows the tooth during the

extrusive movement. This may or may not be benefi-

cial depending on the clinical situation. In other

words, it is sometimes desirable to have the periodon

-

tium follow the tooth and in other situations it is

desirable to move a tooth out of the periodontal sup-

port. This is further discussed under slow versus rapid

eruption of teeth in Chapter 30.

Extrusion with periodontium

Orthodontic extrusion of a single tooth that needs to

be extracted is an excellent method for improvement

of the marginal bone level before the surgical place-

ment of single implants (Figs. 31-15, 31-21). Not only

the bone, but also the soft supporting tissues will

move vertically with the teeth during orthodontic

extrusion. Using tattoo marks in monkeys to indicate

ORTHODONTICS AND PERIODONTICS • 759

Fig. 31-14. Techniques used by Steiner et al. (1981) to bodily advance incisors through the labial bone plate in mon

keys (a,b) and by Engelking & Zachrisson (1982) to retract the incisors to their original position (after the teeth

had remained in extreme labioversion for 8 months) in a study of periodontal regeneration to such tooth movement.

Tis-sue blocks after tooth repositioning (d) show evident bone regeneration.

the mucogingival junction and clinical sulcus bottom,

Kajiyama et al. (1993) made a metric evaluation of the

gingival movement associated with vertical extrusion

of incisors. The results indicated that the free gingiva

moved about 90% and the attached gingiva about 80%

of the extruded distance. The width of the attached

gingiva and the clinical crown length increased sig-

nificantly, whereas the position of the mucogingival

junction was unchanged. Orthodontic extrusion of a "

hopeless" incisor is therefore a useful method also for

esthetic improvement of the marginal gingival level

associated with the placement of implants (Fig. 31-

15).

Extrusion out of periodontium

In teeth with crown-root fracture, or other subgingival

fractures, the goal of treatment may be to extrude the

root out of the periodontium (Fig. 31-16), and then

provide it with an artificial crown. When an increased

distance between the CEJ and the alveolar bone crest

is aimed at, the forced eruption should be combined

with gingival fiberotomy (Pontoriero et al. 1987, Ko-

zlowsky et al. 1988). Berglundh et al. (1991) showed in

animal experiments that when the fiberotomy (i.e.

excision of the coronal portion of the fiber attachment

around the tooth) was performed frequently (every 2

weeks), the tooth was virtually moved out of the bony

periodontium, without affecting the bone heights or

level of the marginal gingiva of the neighboring teeth.

This procedure is illustrated in Fig. 31-16.

Intrusion

Similar to the indications for extrusion, the orthodon-

tic intrusion of teeth has been recommended (1) for

teeth with horizontal bone loss or infrabony pockets,

and (2) for increasing the clinical crown length of

single teeth. However, the benefits of intrusion for

improvement of the periodontal condition around

teeth are controversial.

As mentioned, the intrusion of plaque-infected

teeth may lead to the formation of angular bony de-

fects and increased loss of attachment. When oral

hygiene is inadequate, tipping and intrusion of the

teeth may shift supragingivally located plaque into a

subgingival position, resulting in periodontal de-

struction (Ericsson et al. 1977, 1978). This explains

why professional subgingival scaling is particularly

important during the phase of active intrusion of elon-

gated, tipped and migrated maxillary incisors com-

monly occurring in association with advanced peri-

odontal disease. Even in a healthy periodontal envi-

ronment the question remains as to whether the ortho-

dontic tooth movement intrudes a long epithelial at-

tachment beneath the margin of the alveolar bone or

whether the alveolar crest is continously resorbed in

front of the intruding tooth.

760 • CHAPTER 31

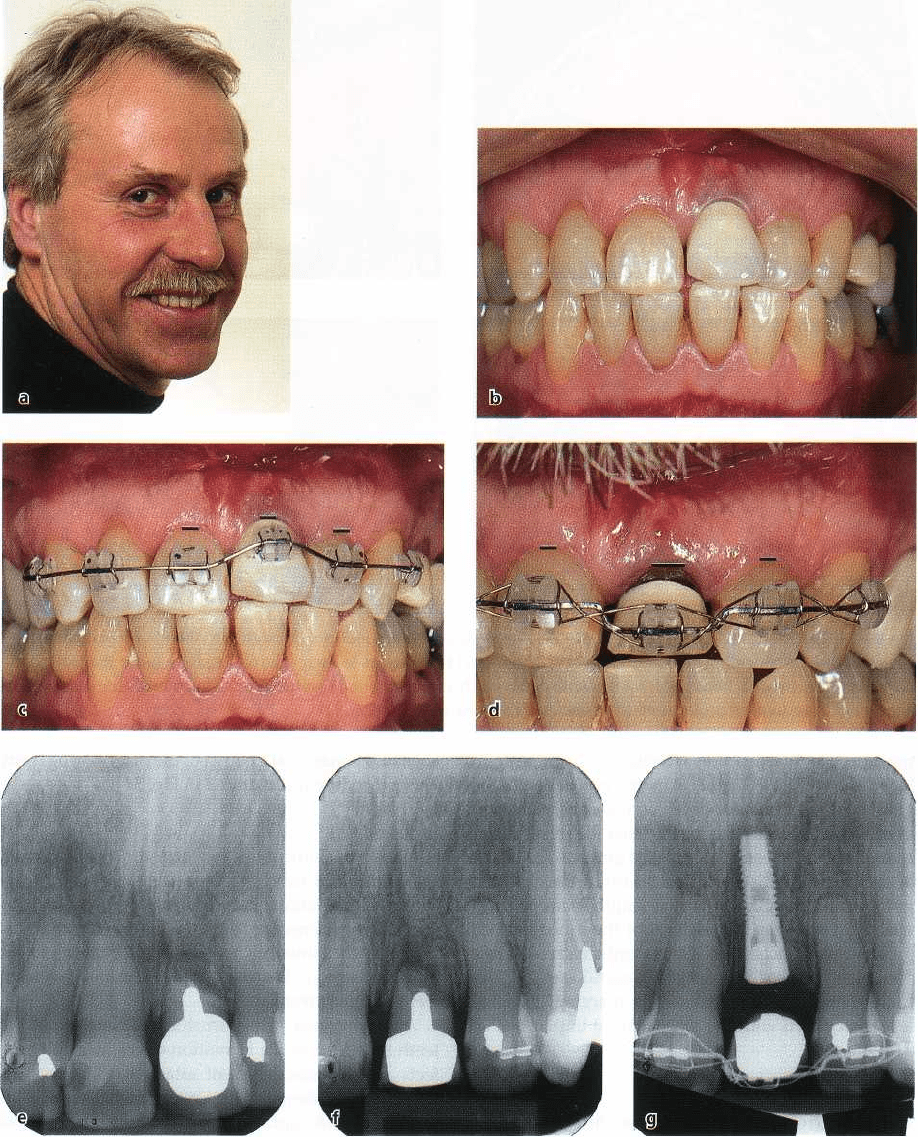

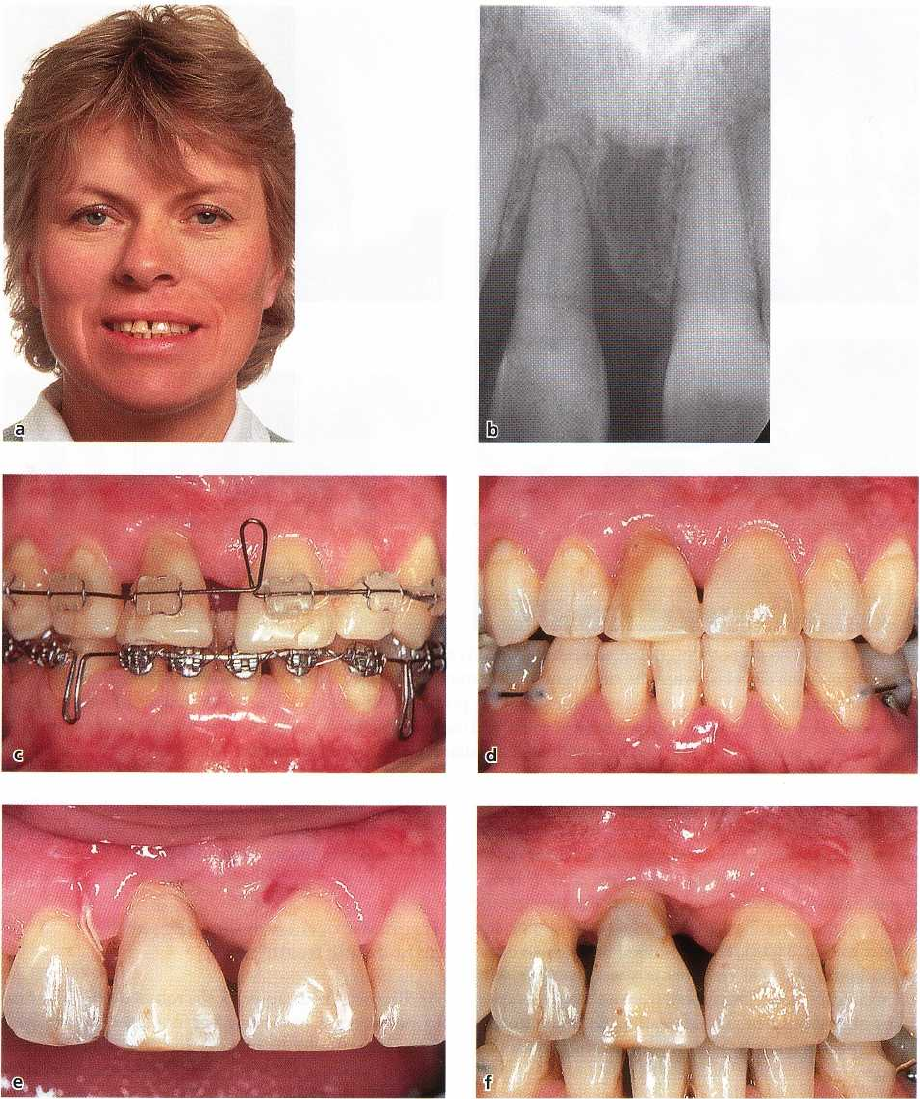

Fig. 31-15. Extrusion with periodontium. Selective extrusion of maxillary left central incisor to improve periodontal

soft and hard tissues before placement of single implant. As shown in (b) to (d), it is necessary to extensively grind

the extruding incisor crown to avoid jiggling with the mandibular teeth. Note evident differences in marginal gingi

-

val levels (lines) on the left central incisor during its extrusion (b-d). (e) to (g) show radiographic appearance at

start, after 4 months and after 10 months, respectively.

Histologic (Melsen 1986, Melsen et al. 1988) and the axis of the incisors with light forces was initiated

clinical

(Melsen et al. 1989) studies indicate that new following flap surgery. Histologic analysis showed

attachment is

possible associated with orthodontic new cementum formation and connective tissue at-intrusion of teeth. In

monkey experiments, periodon- tachment on the intruded teeth, by an average of 1.5 tal tissue breakdown was

induced and intrusion along mm, provided a healthy gingival environment was

ORTHODONTICS AND PERIODONTICS • 761

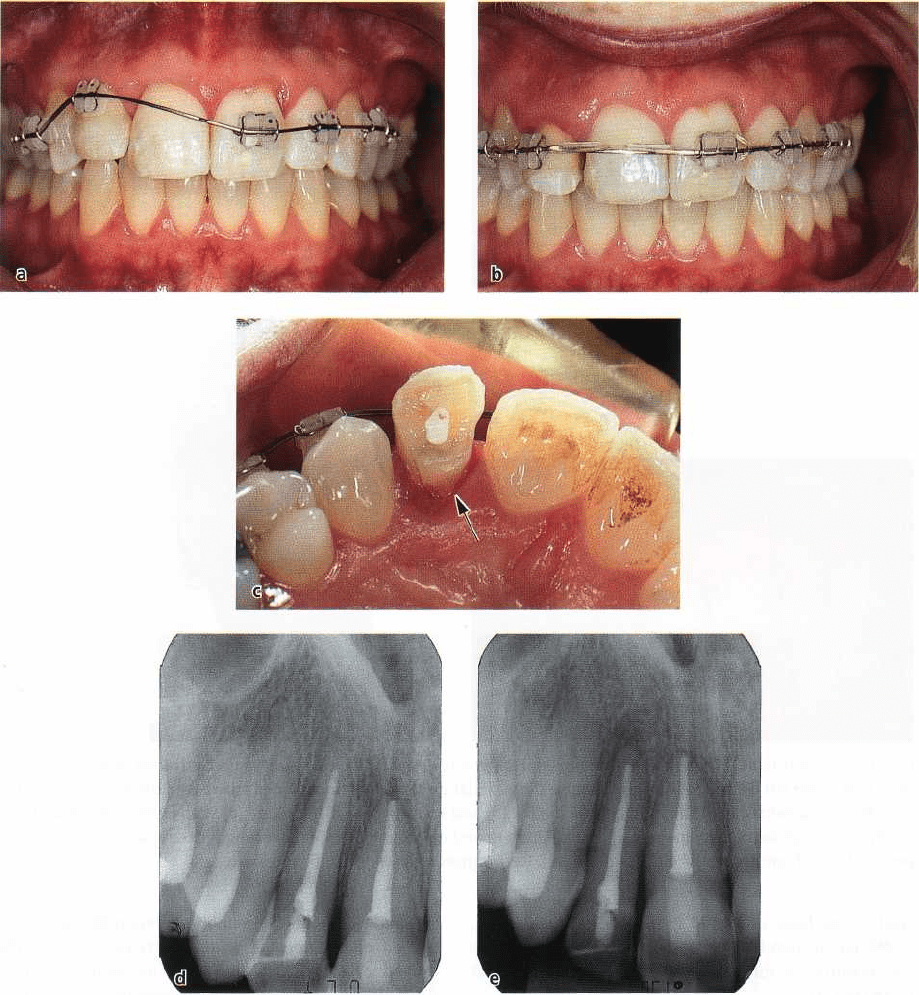

Fig. 31-16. Extrusion out of periodontium. Due to subgingival crown-root fracture on the maxillary right lateral in

cisor (a,d), this tooth was extruded out of the periodontium with a continous force (a-b) and fiberotomy was made

with two-week intervals. The amount of extrusion is evident by comparison of the relationship between lateral and

central incisor root ends in (d) and (e). Having moved the fracture line to a supragingival position (arrow in c), the

tooth can now be safely restored.

maintained throughout the tooth movement. The in-

creased activity of periodontal ligament cells and the

approximation of formative cells to the tooth surface

was suggested to contribute to the new attachment. In

the clinical study, the periodontal condition was

evaluated following the intrusion of extruded and

spaced incisors in patients who had advanced peri-

odontal disease. Judging from clinical probing depths

and radiography, there was despite a large individual

variation a beneficial effect on clinical crown lengths

and marginal bone levels in many cases.

However, the reported clinical and histologic find-

ings associated with a combined orthodontic-peri-

odontal approach must be assessed with great cau-

tion, and these findings have not been confirmed by

others. Furthermore, new techniques like the GTR and

other regenerative procedures (see below) would ap-

pear to be more promising when it comes to creation

of new attachment.

Similar to the case with extrusion, metric and his-

tologic studies have been made after experimental

intrusion of teeth in monkeys. According to Murakaini

et al. (1989), the gingiva moved only about 60%

of the

distance when the teeth were intruded with a

762 • CHAPTER 31

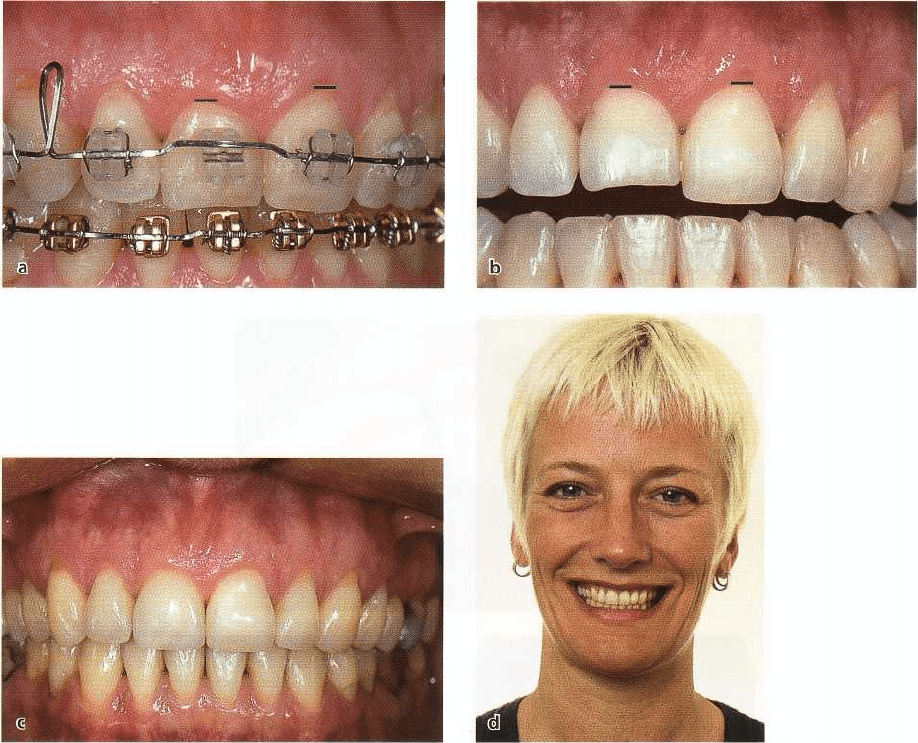

Fig. 31-17. Adult female patient in whom the clinical crown length of the maxillary right central incisor was shorter

than that of the left central incisor (a). Because the sulcular depths were normal, the crown lengths were corrected

by orthodontic intrusion of the right central incisor (b) and restoring the incisal edge (b) with enamel-bonded ul

-

trathin porcelain laminate veneer (c,d). The alignment and correction of the crown length discrepancy has im

-

proved the esthetic appearance of the dentition. Restoration courtesy of Dr S. Toreskog.

continuous force of 80-100 g. However, Kokich et al.

(

1984) recommended an interrupted, continuous force

for levelling of gingival margins on supra-erupted

teeth (Fig. 31-17).

The key to understanding why intrusion can be

used to increase clinical crown length is related to the

subsequent restorative treatment. When orthodontic

intrusion is used for levelling of the gingival margins

to desired heights, such teeth must then be provided

with porcelain laminate veneers or crowns (Fig. 31-

17).

Regenerative procedures and orthodontic

tooth movement

The development of barrier membranes to prevent

cells of the epithelium and gingival connective tissue

from colonizing the decontaminated root surface, as

well as the use of Emdogain, would appear to provide

a

distinct improvement in orthodontic therapy in the

periodontally compromised patient. New supracre-

stal and periodontal ligament collagen fibers may be

gained on the tension side, which can transfer the

orthodontic force stimulus to the alveolar bone (Die-

drich 1996). In theory, the regenerative techniques

would be advantageous associated with both extru-

sion and intrusion of teeth with infrabony defects, and

for uprighting of tipped molars with mesial angular

lesions. Moreover, if the epithelium can be prevented

from proliferating apically, a bodily tooth movement

into or through an intraosseous defect could eliminate

the bony pocket more effectively than in the past (Fig.

31-11).

So far, however, relatively little clinical information

is

available about the use of different regenerative

procedures in connection with orthodontic treatment.

Diedrich (1996) reported an experiment in dogs in

which orthodontic intrusion with flap surgery and

GTR were compared with flap surgery only on perio-

dontally affected teeth. In the presence of minimal or

no round cell infiltration, the marking notch was lo-

cated beneath the alveolar margin indicating that new

attachment had formed. The potential of the intru-

ORTHODONTICS AND PERIODONTICS •

7

6

3

Fig. 31-18. Pathologic tooth migration as a result of an advanced periodontal lesion in adult female patient (a).

Se

vere intraosseous defect between the right central and lateral incisors (b). Three months after GTR

treatment

(GoreTex membrane) partial reossification is evident (c), possibly with new attachment. Orthodontic

leveling (d)

with controlled space closure and intrusion of the lateral incisor. Result 6 months after orthodontic

tooth move

ments shows no root resorption and a consolidated alveolar crest (e). From Diedrich (1996).

sive/regenerative mechanism was most impressive

within the interradicular area. Some clinical observa-

tions (Nemcovsky et al. 1996, Stelzel & Flores-de-Ja-

coby 1998, Rabie et al. 2001) confirm that different

regenerative procedures may enrich the therapeutic

spectrum in combined periodontal/orthodontic ap-

proaches (Fig. 31-18). The combined regenerative and

periodontal surgical treatments used together with

orthodontic tooth movements create new perspec-

tives and should be an interesting field for further

experiments on adults with severe loss of periodontal

tissues.

However, other clinical trials have demonstrated

that treatment results with barrier membranes in the

GTR technique may vary between different patients

and that the method is operator and technique-sensi-

tive (Leknes 1995). The patient's oral hygiene during

the healing phase is critical, and inflammation around

the membrane, particularly if it becomes exposed and

contaminated, may lead to discouraging clinical re-

sults with marked gingival retraction (Fig. 31-19).

Since the membrane is covered in the GBR tech-

nique, the risk for inflammation is reduced. The pos-

sibility for orthodontic movement of teeth into alveo-

lar processes with deficient bone volume may thus be

improved (Basdra et al. 1995). Preorthodontic GBR of

markedly constricted alveolar ridges also has the ad-

vantage that tooth movement through cancellous

bone is easier, and the formation of interfering gingi-

val invaginations can be reduced.

Traumatic occlusion (jiggling) and

orthodontic treatment

As discussed in Chapter 15, the role of occlusal trauma

in periodontal treatment has not been determined.

From an orthodontic perspective, it is of interest that

several studies indicate that traumatic occlusion

forces (1) do not produce gingival inflammation or

loss

of attachment in teeth with healthy periodontium,

(2)

do not aggravate and cause spread of gingivitis or

cause loss of attachment in teeth with established

gingivitis, (3) may aggravate an active periodontitis

lesion, i.e. be a co-destructive factor in an ongoing

process of periodontal tissue breakdown (in one way

or another favor the apical proliferation of plaque-in-

duced destruction), and (4) may lead to less gain of

attachment after periodontal treatment – non-surgical

or surgical.

A major problem in this regard is the lack of establ

-

ished and reliable criteria to identify and quantitate

different degrees of traumatic occlusion. Various clini

-

cal and radiographic indications, such as unfavorable

764 • CHAPTER

31

Fig. 31-19. Adult female periodontitis patient with marked vertical bone loss around the maxillary right central inci

sor before (a,b), during (c) and after (d) orthodontic treatment. Attempt to improve the periodontal situation by

means of GTR treatment failed. Due to infection around the GoreTex membrane (e) marked gingival retraction oc

-

curred (f).

crown/root ratio, increased tooth mobility, widened

periodontal ligament space, angular bone loss, altera-

tions in root morphology, etc. are uncertain and insuf-

ficient in diagnosis of occlusal trauma, and there have

been few scientific clinical reports to evaluate these

signs (Jin & Cao 1992).

The extent to which it is necessary to avoid, or

reduce, occlusal trauma during orthodontic treatment

is controversial and unsupported by scientific evi-

dence. Some orthodontists use bite-planes in virtually

every periodontal case with bone deformities, to re-

duce occlusal trauma and for the purpose of shallow-

ing the bony defects, as teeth supra-erupt. However,

independent studies have shown that surgical pocket

elimination including bone sculpturing offers no ad-

vantage compared with more conservative periodon

tal

treatment (Ramfjord 1984), and apparently there is

little

need to shallow or eliminate bony deformities. It