Jacques J., Raimondo M. Semi-markov risk models for finance, insurance and reliability

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

178 Chapter 5

1.03 0.5

0.53

1.5 0.5

q

−

==

−

(2.12)

and so we get the option value

[]

1

(80,0) 40 (1 ) 0 20.5825.

1.03

fin

Cqq=×+−×= (2.13)

2.2 Multi-Period Model

2.2.1 Case Of Two Periods

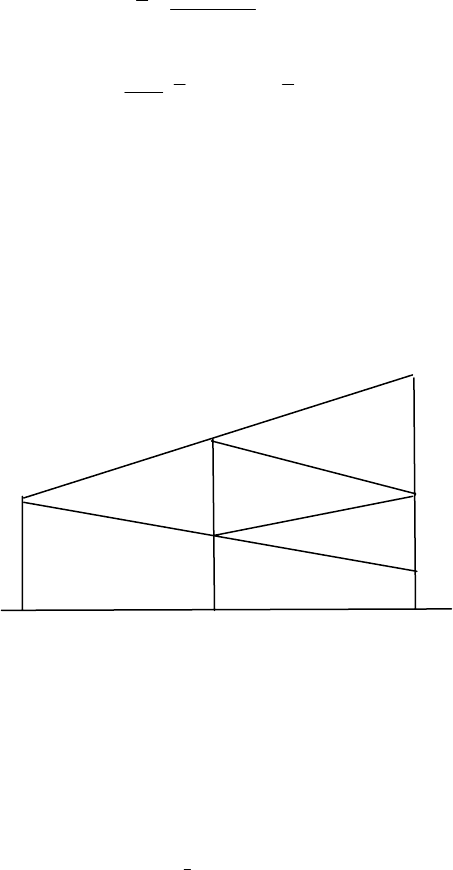

The two following figures show how the model with two periods works.

Here we have to evaluate not only the value of the call at the origin but also at the

intermediary time t=1.

0

1

2

S

uS

uuS

dS

udS

ddS

Figure 2.2: two-period model: scenarios for the underlying asset

Using the notation ( , ), 0,1, 2CSt t

=

in which the second variable represents the

time, here 0, 1 or 2, the first one is the value of the underlying asset at this

considered time.

Here too, as in the case of only one period, the call values will be assessed with

the risk neutral measure as the present values at time t of the “gains” at maturity

t=2 i.e.:

(

)

(,2).

q

ECS (2.14)

Black & Scholes extensions 179

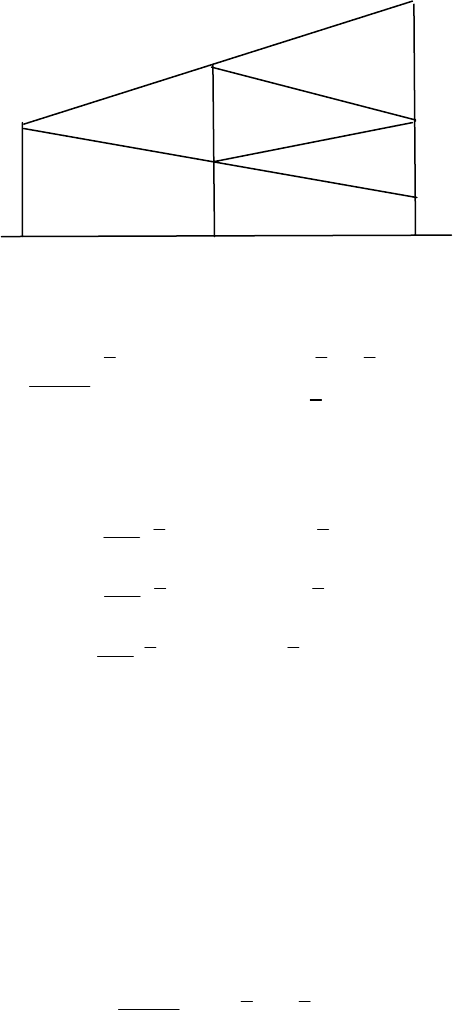

0

1

2

C

Cu

Cuu

Cd

Cud

Cdd

Figure.2.3: two-period model: values of the call

For example we get for t = 0:

{

}

{}

{}

22

0

0

2

22

00

max 0, 2 (1 )

1

(,0) .

(1 )

max 0, (1- ) max 0,

quSKqq

CS

i

udS K q d S K

⎡⎤

−+ −

⎢⎥

=

+

⎢⎥

⋅−+ −

⎣⎦

(2.15)

Remark 2.1 Using a backward reasoning from t=2 to t=1 and from t=1 to t=0, it

is also possible to get this last result since in fact:

[]

2

000

2

000

000

1

(,1) ( ,2)(1)( ,2),

1

1

(,1) ( ,2)(1)( ,2),

1

1

(,0) ( ,1)(1 )( ,1).

1

CuS qC uS qCudS

i

CdS qCudS qCdS

i

C S qC uS q C dS

i

⎡

⎤

=+−

⎣

⎦

+

⎡

⎤

=+−

⎣

⎦

+

=+−

+

(2.16)

Substituting the first two values in the last equality given just above, we get back

to relation (2.15).

2.2.2 Case Of n Periods

If

0

(,)

jnj

ud

CSn

−

represents the call value at t=n if the underlying asset has had j up

movements and nj− down movements and with an initial value of the

underlying asset of (0)S , that is:

{

}

00

( , ) max 0, , 0,1,..., ,

jnj

jnj

ud

CSn udSKj n

−

−

=−=

(2.17)

a straightforward extension of the case of two periods gives the following result:

0

0

1

(,0) (1 ) ()

(1 )

jnj

n

jnj

n

ud

j

n

CS q q C n

j

i

−

−

=

⎛⎞

=−

⎜⎟

+

⎝⎠

∑

(2.18)

180 Chapter 5

and similar results for intermediary time values.

From the computational point of view, Cox and Rubinstein introduced the

minimum number of up movements a so that the call will be “in the money”, that

will mean that the holder has the advantage to exercise his option; clearly, this

integer is given by:

{

}

0

min : .

jnj

ajNudSK

−

=∈ >

(2.19)

Of course, if a is strictly larger than n, the call will always finish “out of the

money” so that the call value at t=n is null.

From relation (2.19), we get:

1

0

0

1

log

1,

log

n

jnj

KS d

ud S K a

ud

−−

−

−

⎢⎥

=

⇔= +

⎢⎥

⎣⎦

(2.20)

x

⎢⎥

⎣⎦

representing the larger integer smaller than or equal to the real x.

From Chapter 1, section 5.1, we know that if X is a r.v. having a binomial

distribution with parameters (n,q), we have:

()

1(1)((,;)).

n

jnj

ja

n

PX a q q Bnqa

j

−

=

⎛⎞

>− = − =

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

∑

(2.21)

As we have (see Cox, Rubinstein (1985), p.178):

1

1,

i

q

u

+

<

<

(2.22)

it follows that the quantity

'q defined below is such that 0'1q

<

< and so the call

value can be written in the form:

00

(,0) (,';) (,;),

(1 )

1

,' .

1

fin

n

K

C S SBnq a Bnqa

i

id u

qqq

ud i

=−

+

+−

==

−+

(2.23)

In conclusion, the binomial distribution is sufficient to compute the call values.

2.2.3 Numerical Example

Coming back to the preceding example for which

0

80, 80, 1.5, 0.5, 3%,SKudi===== (2.24)

and

0.53q = but now for n=2, we get:

1.5

' 0.6 0.7718

1.03

q =×= (2.25)

and consequently

(80,0) 26.4775.C

=

(2.26)

Black & Scholes extensions 181

3 THE BLACK-SCHOLES FORMULA AS LIMIT OF

THE BINOMIAL MODEL

3.1 The Log-Normality Of The Underlying Asset

Since nowadays financial markets operate in continuous time, we will study the

asymptotic behaviour of the CRR formula (2.23) to obtain the value of a call at

time 0 and of maturity T.

To begin with, we will work with a discrete time scale on [0,T] with a unit time

period h defined by n=T/h or more precisely /nTh=

⎢

⎥

⎣

⎦

.

Moreover, if i represents the annual interest rate, the rate for a period of length h

called

ˆ

i is defined by the relation:

ˆ

(1 ) (1 )

nT

ii

+

=+

, (3.1)

so that

ˆ

(1 ) 1.

T

n

ii

=

+−

(3.2)

If

n

J

represents the r.v. giving the number of ascending movements of the

underlying asset, we know that:

(,)

n

J

Bnq≺ (3.3)

and so, starting from

0

,S the value of the underlying asset at the end of period n

is given by

,,

0

() .

nn

JnJ

Sn u d S

−

= (3.4)

It follows that

0

()

log log log .

n

Sn u

J

nd

Sd

=+ (3.5)

The results of the binomial distribution (see Chapter 1, section 5.1) imply that

0

2

0

2

2

2

()

ˆ

log ,

()

ˆ

var log ,

ˆˆ

log ,

ˆ

(1 ) log .

Sn

En

S

Sn

n

S

qd

u

qq

d

μ

σ

μσ

σ

⎛⎞

=

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

⎛⎞

=

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

=+

⎛⎞

=−

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(3.6)

To obtain a limit behaviour, for every fixed n, we must introduce a dependence

of u, d and q with respect to /nTh=

⎢

⎥

⎣

⎦

so that

182 Chapter 5

22

ˆ

lim ( ) ,

ˆ

lim ( ) ,

n

n

nn T

nn T

μα

σσ

→∞

→∞

=

=

(3.7)

,

α

σ

being constant values as parameters of the limit model. As an example, Cox

and Rubinstein (1985) select the values

/

1

,( ),

11

/.

22

T

Tn

n

ue d e

u

qTn

σ

σ

α

σ

−

===

=+

(3.8)

This choice leads to the values:

222

ˆ

() ,

ˆ

() .

nn T

T

nn T

n

μ

α

σσα

=

⎛⎞

=−

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(3.9)

Using a version of the central limit theorem for independent but non-identically

distributed r.v., the authors show that

0

()/Sn S

converges in law to a log-normal

distribution for n →∞

.

More precisely, we have:

0

()

ˆ

log ( )

(),

ˆ

Sn

nn

S

Pxx

n

μ

σ

⎛⎞

−

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

≤→Φ

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(3.10)

Φ being as defined in Chapter 1, section 5.3, the distribution function of the

reduced normal distribution provided that the following condition is satisfied:

33

3

ˆˆ

log (1 ) log

0.

ˆ

n

qu q u

n

μμ

σ

→∞

−+− −

⎯

⎯⎯→

(3.11)

This condition is equivalent to

22

(1 )

0

(1 )

qq

nq q

−+

→

−

(3.12)

which is true from assumption (3.8).

This result and the definition given in Chapter 1, section 5.4, give the next

proposition:

Proposition 3.1(Cox and Rubinstein (1985))

Under the assumptions (3.8), the limit law of the underlying asset is a lognormal

law with parameters

2

(, )TT

ασ

or

0

()

log

()().

ST

T

S

Pxx

T

α

σ

−

≤=Φ

(3.13)

Black & Scholes extensions 183

In particular, it follows that:

2

22

2

0

2

0

()

,

()

var ( 1).

TT

TT T

ST

Ee

S

ST

ee

S

σ

α

ασ σ

+

+

⎛⎞

=

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

⎛⎞

=

−

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(3.14)

3.2 The Black-Scholes Formula

Starting from the result (2.21) and using Proposition 3.1 under the risk neutral

measure, Cox & Rubinstein (1985) proved that the asymptotic value of the call is

given by the famous

Black and Scholes (1973) formula:

()

(,) () (1 ) ( ),

ln / (1 )

1

.

2

T

T

CST S x K i x T

SK i

xT

T

σ

σ

σ

−

−

=Φ − + Φ −

+

=+

(3.15)

Here, we note the call using the maturity as second variable and S representing

the value of the underlying asset at time 0.

The interpretation of the Black and Scholes formula can be given with the

concept of a hedging portfolio.

Indeed, we already know that in the CRR model, the value of the call takes the

form:

CS B

=

Δ+

,

(3.16)

Δ

representing the proportion of assets in the portfolio and B the quantity

invested on the non-risky rate at t=0.

From the result (3.16), at the limit, we obtain:

(),

(1 ) ( ).

T

x

B

Ki x T

σ

−

Δ=Φ

=− + Φ −

(3.17)

So, under the assumption of an efficient market, the hedging portfolio is also

known in continuous time.

Remark 3.1 This hedging portfolio must of course, at least theoretically, be

rebalanced at every time s on [0,T]. Rewriting the Black and Scholes formula for

computing the call at time s, the underlying asset having the value S, we get:

()

()

()

(), (1 ) ( ),

ln / (1 )

1

.

2

Ts

Ts

x

BKi x Ts

SK i

xTs

Ts

σ

σ

σ

−−

−−

Δ=Φ =− + Φ − −

+

=+−

−

(3.18)

184 Chapter 5

Of course a continuous rebalancing and even a portfolio with frequent time

changes are not possible due to the transaction costs.

4 THE BLACK-SCHOLES CONTINUOUS TIME MODEL

4.1 The Model

In fact, Black and Scholes used a continuous time model for the underlying asset

introduced by Samuelson (1965).

On a complete filtered probability space

(

)

(

)

Pt

t

,0,,, ≥

ℑ

ℑ

Ω

(see Definition 7.2

of Chapter 1) the stochastic process

(

)

(), 0SStt

=

≥

(4.1)

will now represent the time evolution of the underlying asset.

The basic assumption is that the stochastic dynamic of the S-process is given by

0

() () () (),

(0) ,

dSt Stdt StdBt

SS

μ

σ

=

+

=

(4.2)

where the process

[

]

((), 0, )

B

Bt t T=∈is a standard Brownian process (see

Chapter 1, section 9 adapted to the considered filtration.

4.2 The Itô Or Stochastic Calculus

In (4.2), the equation is in fact a stochastic differential equation or an Itô

differential equation as the term dB(t) must be considered formally since we

know that the sample paths of a Brownian motion are a.s. non-differentiable (see

Chapter 1,

Proposition 9.1).

That is why Itô (1944) created a new type of calculus, called stochastic calculus

in which the integral with respect to b is defined as follows for every stochastic

process

[]

(

)

(), 0,

f

ft t T=∈ adapted and integrable:

[]

1

1

0

0

(,) (,) lim (,) ( ,) (,),

t

n

kk k

k

k

ft dBt ft Bt Bt

ω

ωωωω

−

+

→∞

=

=−

∑

∫

(4.3)

where

(

)

[

]

01 0

, ,..., ,( 0, , 0, )

nn

tt t t t tt T==∈ is a subdivision of

[

]

0,t whose norm

tends to 0 for n tending to

+∞ , the limit being the so-called uniform convergence

in probability (see Protter (1990)).

Conversely, using the differential notation, if the stochastic process

[

]

(

)

(), 0,tt T

ξξ

=∈ is declared to satisfy the following relation, called the Itô

differential of

ξ

:

Black & Scholes extensions 185

d

ξ

(t)

=

a(t)dt

+

b(t)dB(t)

; (4.4)

then:

00

() (0) ( ) ( ) ( ).

tt

tasdsbsdBs

ξξ

−= +

∫∫

(4.5)

For our applications, the main result is the so-called Itô´s lemma or the Itô

formula, which is equivalent to the rule of derivatives for composed functions in

the classical differential calculus.

Let f be a function of two non-negative real variables x ,t such that

00

,, , .

xxxt

fC fff C

+

+

××

∈∈

(4.6)

Then the composed stochastic process

f (

ξ

(t), t),t ≥ 0

(

)

(4.7)

is also Itô differentiable and its stochastic differential is given by:

(

)

2

2

22

((),)

1

((),)() ((),) ((),) ()

2

( ( ), ) ( ) ( ).

df tt

ff

ttat tt f ttbt dt

xtx

f

ttbtdBt

x

ξ

∂∂∂

ξξ ξ

∂∂∂

∂

ξ

∂

=

⎡⎤

++

⎢⎥

⎣⎦

+

(4.8)

Remark 4.1 Compared with the classical differential calculus, we know that in

this case, we should have:

()

( ( ), ) ( ( ), ) ( ) ( ( ), )

( ( ), ) ( ) ( ).

ff

df tt ttat tt dt

xt

f

ttbtdBt

x

∂∂

ξξ ξ

∂∂

∂

ξ

∂

⎡

⎤

=+

⎢

⎥

⎣

⎦

+

(4.9)

So, the difference between relations (4.8) and (4.9) is the supplementary term

1

2

∂

2

∂

2

2

x

f (

ξ

(t),t)b

2

(t)

(4.10)

appearing in (4.8) and which is null iff in two cases:

1) f is a linear function of x,

2) b is identically equal to 0.

Examples

1) For

ξ

given by:

d

ξ

(t)

=

dB(t),

ξ

(0) = 0.

(4.11)

Using notation (4.4), we get:

a(t)=0, b(t)=1. (4.12)

186 Chapter 5

With the aid of the Itô formula, the value of

2

()dt

ξ

is given by

d

2

ξ

(t ) = 2

ξ

(t ). 0 + 0 +

1

2

.2.1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

dt + 2

ξ

(t).1. dB(t),

(4.13)

and so

2

() 2 (). ().dB t dt B t dB t=+ (4.14)

As we can see, the first term is the supplementary term with respect to the

classical formula and is called the drift.

2) Proceeding as for the preceding example, we get for

()

B

t

de :

() () ()

1

().

2

Bt Bt Bt

de e dt e dB t=+ (4.15)

Here, the drift is given by the first term of the second member of (4.15).

4.3 The Solution Of The Black-Scholes-Samuelson Model

Let us go back to the model (4.2) given by:

.)0(

),()()()(

0

SS

tdBt

S

dtt

S

td

S

=

+

=

σ

μ

(4.16)

Using the Itô formula for lnS(t), we get:

2

ln ( ) ( )

2

dSt dt dBt

σ

μσ

⎛⎞

=− +

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(4.17)

and so by integration:

2

0

ln ( ) ln ( ).

2

St S t Bt

σ

μσ

⎛⎞

−=− +

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(4.18)

Since for every fixed t, B(t) has a normal distribution with parameters (0,t) - t for

the variance - (see Chapter 1,

Definition 9.1), this last result shows that the r.v.

S(t)/S

0

has a log-normal distribution with parameters

2

2

,

2

tt

σ

μσ

⎛⎞

⎛⎞

−

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

⎝⎠

and so:

2

0

2

0

()

log ,

2

()

var log .

St

E

t

S

St

t

S

σ

μ

σ

⎛⎞

⎛⎞

=−

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

⎝⎠

⎛⎞

=

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(4.19)

Of course, from result (4.18), we obtain the explicit form of the trajectories of the

S-process:

2

2

()

0

() .

t

B

t

St Se e

σ

μ

σ

⎛⎞

−

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

= (4.20)

This process is called a geometric brownian motion.

Black & Scholes extensions 187

The fact of having the log-normality confirms the CRR process at the limit as,

indeed, a lot of empirical studies show that, for an efficient market, stock prices

are well adjusted with such a distribution.

From properties of the log-normal distribution (see Chapter 1, section 5.4), we

obtain:

2

0

2

0

()

,

()

var ( 1).

t

tt

St

Ee

S

St

ee

S

μ

μσ

⎛⎞

=

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

⎛⎞

=

−

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

(4.21)

So, we see that the mean value of the asset at time t is given as if the initial

amount S

0

was invested at the non-risky instantaneous interest rate

μ

and that its

value is above or below S

0

following the “hazard” variations modelled with the

Brownian motion.

We also see that the variance of S(t) increases with time in conformity with the

fact that, for long time periods, variations of the asset are very difficult to predict.

The explicit relation (4.20) can also be written in the form:

2

2

()

0

()

.

t

Bt

St

e

Se

σ

μ

σ

⎛⎞

−

⎜⎟

⎜⎟

⎝⎠

= (4.22)

This allows us to distinguish three cases:

(i)

2

.

2

σ

μ

= (4.23)

If so, the evolution of the asset is that of a pure Brownian exponential.

(ii)

2

.

2

σ

μ

> (4.24)

Here, S(t) will vary faster than the pure Brownian exponential and so, we may

expect at certain times large gains but also large losses parallel with the time

evolution of the pure brownian exponential

(iii)

2

.

2

σ

μ

< (4.25)

Here, the situation is similar but the evolution is opposed to that of the pure

Brownian exponential.

From the second result of (4.21), it is also clear that the expectations of large

gains - and losses! - are better for large values of

σ

; that is why

σ

is called the

volatility of the considered asset.

It follows that a market with high volatility will attract risk lover investors and

not risk averse investors

From the explicit form, it is not difficult to simulate trajectories of the S-process.

The next figure shows a typical form.