Jacques I. Mathematics for Economics and Business

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Linear Equations

40

Example

Solve the equations

2x − 4y = 1

5x − 10y = 5/2

Solution

Step 1

The variable x can be eliminated by multiplying the first equation by 5, multiplying the second equation

by 2 and subtracting

10x − 20y = 5

10x − 20y = 5 −

0 = 0

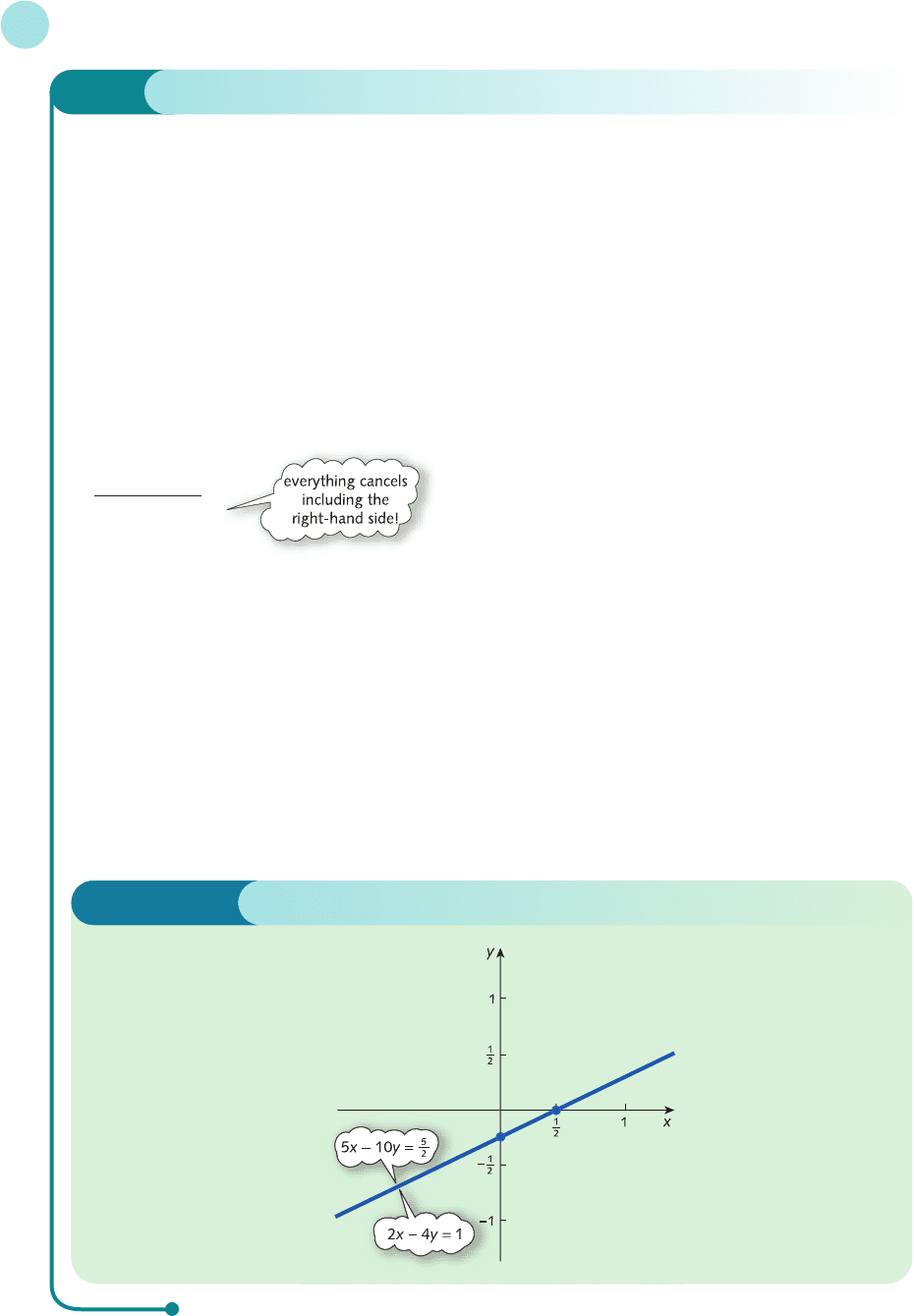

Again, it is easy to explain this using graphs. The line 2x − 4y = 1 passes through (0, −1/4) and (1/2, 0).

The line 5x − 10y = 5/2 passes through (0, −1/4) and (1/2, 0). Consequently, both equations represent the

same line. From Figure 1.12 the lines intersect along the whole of their length and any point on this line

is a solution. This particular system of equations has infinitely many solutions. This can also be deduced

algebraically. The equation involving y in step 2 is

0y = 0

which is true for any value of y.

Figure 1.12

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 40

These examples show that a system of equations can possess a unique solution, no solution

or infinitely many solutions. Algebraically, this can be detected in step 2. If the equation result-

ing from the elimination of x looks like

×=

then the equations have a unique solution, or if it looks like

×=

then the equations have no solution, or if it looks like

×=

then the equations have infinitely many solutions.

It is interesting to notice how the graphical approach ‘saved the day’ in the previous two

examples. They show how useful pictures are as an aid to understanding in mathematics.

zero

yzero

any non-zero numberyzero

any numberyany non-zero number

1.2 • Algebraic solution of simultaneous linear equations

41

Practice Problem

2 Attempt to solve the following systems of equations

(a)

3x − 6y =−2 (b) −5x + y = 4

−4x + 8y =−110x − 2y =−8

Comment on the nature of the solution in each case.

We now show how the algebraic method can be used to solve three equations in three

unknowns. As you might expect, the details are more complicated than for just two equations,

but the principle is the same. We begin with a simple example to illustrate the general method.

Consider the system

x + 3y − z = 4 (1)

2x + y + 2z = 10 (2)

3x − y + z = 4 (3)

The objective is to find three numbers x, y and z which satisfy these equations simultaneously.

Our previous work suggests that we should begin by eliminating x from all but one of the

equations.

The variable x can be eliminated from the second equation by multiplying equation (1)

by 2 and subtracting equation (2):

2x + 6y − 2z = 8

2x + y + 2z = 10 −

5y − 4z =−2 (4)

Similarly, we can eliminate x from the third equation by multiplying equation (1) by 3 and sub-

tracting equation (3):

3x + 9y − 3z = 12

3x − y + z = 4 −

10y − 4z = 8 (5)

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 41

At this stage the first equation is unaltered but the second and third equations of the system

have changed to equations (4) and (5) respectively, so the current equations are

x + 3y − z = 4 (1)

5y − 4z =−2 (4)

10y − 4z = 8 (5)

Notice that the last two equations constitute a system of just two equations in two unknowns, y

and z. This, of course, is precisely the type of problem that we already know how to solve. Once

y and z have been calculated, the values can be substituted into equation (1) to deduce x.

We can eliminate y in the last equation by multiplying equation (4) by 2 and subtracting

equation (5):

10y − 8z =−4

10y − 4z = 8 −

−4z =−12 (6)

Collecting together the current equations gives

x + 3y − z = 4 (1)

5y − 4z =−2 (4)

−4z =−12 (6)

From the last equation,

z ==3 (divide both sides by −4)

If this is substituted into equation (4) then

5y − 4(3) =−2

5y − 12 =−2

5y = 10 (add 12 to both sides)

y = 2 (divide both sides by 5)

Finally, substituting y = 2 and z = 3 into equation (1) produces

x + 3(2) − 3 = 4

x + 3 = 4

x = 1 (subtract 3 from both sides)

Hence the solution is x = 1, y = 2, z = 3.

As usual, it is possible to check the answer by putting these numbers back into the original

equations (1), (2) and (3)

1 + 3(2) − 3 = 4 ✓

2(1) + 2 + 2(3) = 10 ✓

3(1) − 2 + 3 = 4 ✓

The general strategy may be summarized as follows. Consider the system

?x + ?y + ?z = ?

?x + ?y + ?z = ?

?x + ?y + ?z = ?

where ? denotes some numerical coefficient.

−12

−4

Linear Equations

42

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 42

Step 1

Add/subtract multiples of the first equation to/from multiples of the second and third equa-

tions to eliminate x. This produces a new system of the form

?x + ?y + ?z = ?

?y + ?z = ?

?y + ?z = ?

Step 2

Add/subtract a multiple of the second equation to/from a multiple of the third to eliminate y.

This produces a new system of the form

?x + ?y + ?z = ?

?y + ?z = ?

?z = ?

Step 3

Solve the last equation for z. Substitute the value of z into the second equation to deduce y.

Finally, substitute the values of both y and z into the first equation to deduce x.

Step 4

Check that no mistakes have been made by substituting the values of x, y and z into the original

equations.

It is possible to adopt different strategies from that suggested above. For example, it may be

more convenient to eliminate z from the last equation in step 2 rather than y. However, it is

important to notice that we use the second equation to do this, not the first. Any attempt to use

the first equation in step 2 would reintroduce the variable x into the equations, which is the last

thing we want to do at this stage.

1.2 • Algebraic solution of simultaneous linear equations

43

Example

Solve the equations

4x + y + 3z = 8 (1)

−2x + 5y + z = 4 (2)

3x + 2y + 4z = 9 (3)

Solution

Step 1

To eliminate x from the second equation we multiply it by 2 and add to equation (1):

4x + y + 3z = 8

−4x + 10y + 2z = 8 +

11y + 5z = 16 (4)

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 43

To eliminate x from the third equation we multiply equation (1) by 3, multiply equation (3) by 4 and subtract:

12x + 3y + 9z = 24

12x + 8y + 16z = 36 −

−5y − 7z =−12 (5)

This produces a new system:

4x + y + 3z = 8 (1)

11y + 5z = 16 (4)

−5y − 7z =−12 (5)

Step 2

To eliminate y from the new third equation (that is, equation (5)) we multiply equation (4) by 5, multiply

equation (5) by 11 and add:

55y + 25z = 80

−55y − 77z =−132 +

−52z =−52 (6)

This produces a new system

4x + y + 3z = 8 (1)

11y + 5z = 16 (4)

−52z =−52 (6)

Step 3

The last equation gives

z ==1 (divide both sides by −52)

If this is substituted into equation (4) then

11y + 5(1) = 16

11y + 5 = 16

11y = 11 (subtract 5 from both sides)

y = 1 (divide both sides by 11)

Finally, substituting y = 1 and z = 1 into equation (1) produces

4x + 1 + 3(1) = 8

4x + 4 = 8

4x = 4 (subtract 4 from both sides)

x = 1 (divide both sides by 4)

Hence the solution is x = 1, y = 1, z = 1.

Step 4

As a check the original equations (1), (2) and (3) give

−52

−52

Linear Equations

44

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 44

4(1) + 1 + 3(1) = 8 ✓

−2(1) + 5(1) + 1 = 4 ✓

3(1) + 2(1) + 4(1) = 9 ✓

respectively.

1.2 • Algebraic solution of simultaneous linear equations

45

Practice Problem

3 Solve the following system of equations:

2x + 2y − 5z =−5 (1)

x − y + z = 3 (2)

−3x + y + 2z =−2 (3)

As you might expect, it is possible for three simultaneous linear equations to have either no

solution or infinitely many solutions. An illustration of this is given in Practice Problem 8. The

method described in this section has an obvious extension to larger systems of equations.

However, the calculations are extremely tedious to perform by hand. Fortunately there are

many computer packages available which are capable of solving large systems accurately and

efficiently (a matter of a few seconds to solve 10 000 equations in 10 000 unknowns).

Advice

We shall return to the solution of simultaneous linear equations in Chapter 7 when we

describe how matrix theory can be used to solve them. This does not depend on any sub-

sequent chapters in this book, so you might like to read through this material now. Two

techniques are suggested. A method based on inverse matrices is covered in Section 7.2

and an alternative using Cramer’s rule can be found in Section 7.3.

Elimination method The method in which variables are removed from a system of simul-

taneous equations by adding (or subtracting) a multiple of one equation to (or from) a mul-

tiple of another.

Key Terms

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 45

Linear Equations

46

Practice Problems

4 Use the method of elimination to solve the systems of equations given in Section 1.1, Problem 14.

5 Sketch the following lines on the same diagram:

2x − 3y = 6, 4x − 6y = 18, x − y = 3

Hence comment on the nature of the solutions of the following systems of equations:

(a)

2x − 3y = 6 (b) 4x − 6y = 18

x − y = 3 x − y = 3

6 Use the elimination method to attempt to solve the following systems of equations. Comment on the

nature of the solution in each case.

(a)

−3x + 5y = 4 (b) 6x − 2y = 3

9x − 15y =−12 15x − 5y = 4

7 Solve the following systems of equations:

(a)

x − 3y + 4z = 5 (1) (b) 3x + 2y − 2z =−5 (1)

2x + y + z = 3 (2) 4x + 3y + 3z = 17 (2)

4x + 3y + 5z = 1 (3) 2x − y + z =−1 (3)

8 Attempt to solve the following systems of equations. Comment on the nature of the solution in each

case.

(a)

x − 2y + z =−2 (1) (b) 2x + 3y − z = 13 (1)

x + y − 2z = 4 (2) x − 2y + 2z =−3 (2)

−2x + y + z = 12 (3) 3x + y + z = 10 (3)

3

2

3

2

3

2

MFE_C01b.qxd 16/12/2005 10:55 Page 46

section 1.3

Supply and demand analysis

Microeconomics is concerned with the analysis of the economic theory and policy of indi-

vidual firms and markets. In this section we focus on one particular aspect known as market

equilibrium, in which the supply and demand balance. We describe how the mathematics

introduced in the previous two sections can be used to calculate the equilibrium price and

quantity. However, before we do this it is useful to explain the concept of a function. This idea

is central to nearly all applications of mathematics in economics.

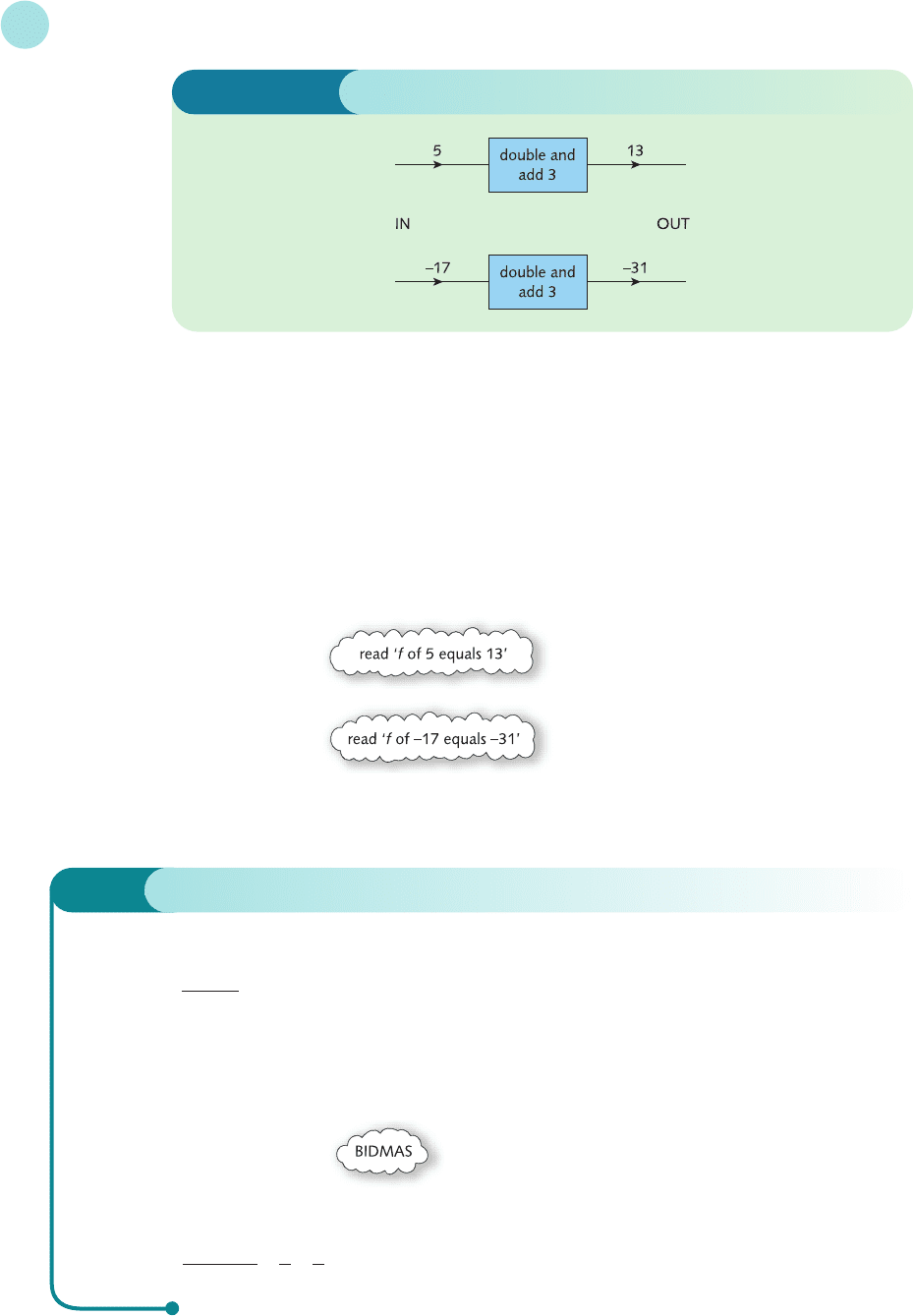

A function, f, is a rule which assigns to each incoming number, x, a uniquely defined

outgoing number, y. A function may be thought of as a ‘black box’ that performs a dedicated

arithmetic calculation. As an example, consider the rule ‘double and add 3’. The effect of this

rule on two specific incoming numbers, 5 and −17, is illustrated in Figure 1.13 (overleaf).

Unfortunately, such a representation is rather cumbersome. There are, however, two alter-

native ways of expressing this rule which are more concise. We can write either

y = 2x + 3 or f(x) = 2x + 3

Objectives

At the end of this section you should be able to:

Use the function notation, y = f(x).

Identify the endogenous and exogenous variables in an economic model.

Identify and sketch a linear demand function.

Identify and sketch a linear supply function.

Determine the equilibrium price and quantity for a single-commodity market

both graphically and algebraically.

Determine the equilibrium price and quantity for a multicommodity market by

solving simultaneous linear equations.

MFE_C01c.qxd 16/12/2005 10:56 Page 47

The first of these is familiar to you from our previous work; corresponding to any incoming

number, x, the right-hand side tells you what to do with x to generate the outgoing number, y.

The second notation is also useful. It has the advantage that it involves the label f, which is used

to name the rule. If, in a piece of economic theory, there are two or more functions, we can use

different labels to refer to each one. For example, a second function might be

g(x) =−3x + 10

and we subsequently identify the respective functions simply by referring to them by name:

that is, as either f or g.

The new notation also enables the information conveyed in Figure 1.13 to be written

f(5) = 13

f(−17) =−31

The number inside the brackets is the incoming value, x, and the right-hand side is the cor-

responding outgoing value, y.

Linear Equations

48

Figure 1.13

Example

(a) If f(x) = 2x

2

− 3x find the value of f(5).

(b) If g(Q) = find the value of g(2).

Solution

(a) Substituting x = 5 into 2x

2

− 3x gives

f(5) = 2 × 5

2

− 3 × 5

= 2 × 25 − 3 × 5

= 50 − 15 = 35

(b) Although the letter Q is used instead of x, the procedure is the same.

g(2) ===

1

3

3

9

3

5 + 2 × 2

3

5 + 2Q

MFE_C01c.qxd 16/12/2005 10:56 Page 48

The incoming and outgoing variables are referred to as the independent and dependent vari-

ables respectively. The value of y clearly ‘depends’ on the actual value of x that is fed into the

function. For example, in microeconomics the quantity demanded, Q, of a good depends on

the market price, P. We might express this as

Q = f(P)

Such a function is called a demand function. Given any particular formula for f(P) it is then a

simple matter to produce a picture of the corresponding demand curve on graph paper. There

is, however, a difference of opinion between mathematicians and economists on how this

should be done. If your quantitative methods lecturer is a mathematician then he or she is likely

to plot Q on the vertical axis and P on the horizontal axis. Economists, on the other hand, norm-

ally plot them the other way round with Q on the horizontal axis. In doing so, we are merely

noting that since Q is related to P then, conversely, P must be related to Q, and so there is a

function of the form

P = g(Q)

The two functions, f and g, are said to be inverse functions: that is, f is the inverse of g and,

equivalently, g is the inverse of f. We adopt the economists’ approach in this book. In sub-

sequent chapters we shall investigate other microeconomic functions such as total revenue,

average cost, and profit. It is conventional to plot each of these against Q (that is, with Q on the

horizontal axis), so it makes sense to be consistent and to do the same here.

Written in the form P = g(Q), the demand function tells us that P is a function of Q but it

gives us no information about the precise relationship between these two variables. To find this

we need to know the form of the function which can be obtained either from economic theory

or from empirical evidence. For the moment we hypothesize that the function is linear so that

P = aQ + b

for some appropriate constants (called parameters), a and b. Of course, in reality, the relation-

ship between price and quantity is likely to be much more complicated than this. However, the

use of linear functions makes the mathematics nice and easy, and the result of any analysis at least

provides a first approximation to the truth. The process of identifying the key features of the real

world and making appropriate simplifications and assumptions is known as modelling. Models

are based on economic laws and help to explain and predict the behaviour of real-world situ-

ations. Inevitably there is a conflict between mathematical ease and the model’s accuracy.

The closer the model comes to reality, the more complicated the mathematics is likely to be.

A graph of a typical linear demand function is shown in Figure 1.14 (overleaf). Elementary

theory shows that demand usually falls as the price of a good rises and so the slope of the line

is negative. Mathematically, P is then said to be a decreasing function of Q.

1.3 • Supply and demand analysis

49

Practice Problem

1 Evaluate

(a)

f(25) (b) f(1) (c) f(17) (d) g(0) (e) g(48) (f) g(16)

for the two functions

f(x) =−2x + 50

g(x) =−

1

/2 x + 25

Do you notice any connection between f and g?

MFE_C01c.qxd 16/12/2005 10:56 Page 49