Jacobson M.Z. Atmospheric Pollution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Per CAAA90, state or local air quality districts overseeing a nonattainment area

were required to develop emission inventories for ROGs, NO

x

(g), and CO(g).

Emissions from mobile, stationary point, area, and biogenic sources were to be includ-

ed in the inventories. The 1990 Act also mandated that computer modeling be carried

out with current and projected future inventories to demonstrate that attainment could

be obtained under proposed reductions in emissions.

CAAA90 created a list of 189 hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) from hundreds of

source categories. Under CAAA90, the U.S. EPA was required to develop emission

standards for each source category under a timetable. For each new or existing source

anticipated to emit more than 10 short tons per year of one HAP or 25 short tons per

year of a combination of HAPs, the U.S. EPA was required to establish a maximum

achievable control technology (MACT) to reduce hazardous pollution from the

source. In selecting MACTS, the U.S. EPA was permitted to consider cost, non-air

quality health and environmental impacts, and energy requirements. Because the use

of a MACT does not necessarily mean that hazardous pollutant concentrations will be

reduced to a safe level,

the U.S. EPA was also required to consult with the Surgeon

General to evaluate the risk resulting from the implementation of each MACT.

The control of toxic air pollutants under CAAA90 differed from the control of

criteria air pollutants. In the former case, the U.S. EPA was required to develop a pro-

gram to control toxic emissions; in the latter, states were required to develop programs

to control criteria air pollutant emissions and their ambient concentrations.

CAAA90 also tightened emission standards for automobiles and trucks, required

additional reductions in emissions of acid-deposition precursors, established a federal

permitting program for point sources of pollution (previously, states were responsible

for permits), and mandated reductions in the emission of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)

to combat stratospheric ozone reduction.

With respect to acid deposition, CAAA90

required a 10 million ton reduction in sulfur dioxide emissions from 1980 levels and a

2 million ton reduction in nitrogen oxide emissions from 1980 levels. With respect to

CFCs, CAAA90 required a complete phase-out of CFCs, Halons (synthetic bromine

containing compounds), and carbon tetrachloride by 2000 and methyl chloroform by

2002. CAAA90 also required the U.S. EPA to publish a list of safe and unsafe substi-

tutes for these compounds and a list of the ozone-depletion potential, atmospheric

lifetimes, and global-warming potentials of all regulated substances suspected of dam-

aging stratospheric ozone. CAAA90 banned the production of nonessential products

releasing ozone-depleting chemicals. Such products included aerosol spray cans

releasing CFCs and certain noninsulating foam.

8.1.9. Clean Air Act Revision of 1997

In 1997, Congress passed the 1997 Clean Air Act Revision (CAAR97), by which it

modified the NAAQSs for ozone and particulate matter (see Table 8.2). The new feder-

al ozone standard is based on an 8-hour average rather than a 1-hour average. The new

averaging time is intended to protect those who spend time working or playing out-

doors, the people most vulnerable to the effects of ozone.

The particulate standard was modified to include a new PM

2.5

standard because

studies have shown that aerosol particles 2.5 m in diameter have more effect on

respiratory illness, premature death, and visibility than do larger aerosol particles

(Section 5.6). The purpose of the new PM

2.5

standard was to reduce risks associated

with disease and early death associated with PM

2.5

.

218 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

8.1.10. Regulation of Interstate and Transboundary Air Pollution

in the United States

As described in Section 6.6.2.4, long-range transport of air pollution is a problem that

affects most countries. International efforts to control transboundary air pollution are

discussed with respect to acid deposition in Section 10.7. Here, control of long-range

transport in and between the United States and its neighbors is discussed.

Interstate transport of air pollution in the United States is recognized by the gov-

ernment through Section 110 of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970, which

requires that SIPs be submitted to the U.S. EPA by each state and contain provisions to

address problems of emissions transported to downwind states. Section 126 of

CAAA70 allows downwind states to file petitions with the U.S. EPA to take action to

reduce emissions in upwind states when such emissions make it difficult for the down-

wind state to meet federal air quality standards.

In 1994, the U.S. EPA itself recognized that it was difficult for some states to

meet federal standards merely by reducing emissions in their own state. As a result,

the Ozone Transport Assessment Group (OTAG), a partnership between the U.S.

EPA, the Environmental Council of the States (ECOS) (37 easternmost states and the

District of Columbia), and several industry and en

vironmental groups, was set up in

1995 (and concluded in 1997) to develop a mechanism to reduce ozone buildup due

to interstate ozone transport, particularly in the northeast United States. In 1997, dur-

ing the period of OTAG, eight northeastern states filed petitions under Section 126 of

the Clear Air Act Amendments requesting the U.S. EPA to take action against 22

upwind states (Alabama, Connecticut, Delawa

re, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky,

Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New

York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia,

Wisconsin, and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia for emitting excess

oxides of nitrogen [NO

x

(g)]. Such emissions were suspected of exacerbating ozone in

the petitioning states. In September 1998, the U.S. EPA implemented a rule [known

as the NO

x

(g) SIP Call] that required these 22 states and the District of Columbia to

submit SIPs that addressed the regional transport of ozone. The rule required reduc-

tions of NO

x

(g) but not reactive organic gases (ROGs) in these states by 2003.

Transboundary pollution between the United States and Canada is formally recog-

nized through the Canada/U.S.

Air Quality Agreement. Article V of the agreement

states that Canada must notify the United States of any proposed projects within 100

km of the border that would be likely to emit more than 90 tons/year of SO

2

(g),

NO

x

(g), CO(g), TSP, or ROGs. On a smaller scale, the United States and Mexico

implemented a cooperative study, the Big Bend Regional Preliminary Visibility Study,

to examine causes of visibility reduction in Big Bend National Park. In 1998, this pre-

liminary study concluded that sources in both the United States and Mexico degraded

visibility in the park, depending on the wind conditions.

8.1.11. Smog Alerts

Because ozone is a criteria pollutant and its mixing ratios exceed federal and state

standards more than do those of any other pollutant and because high levels of ozone

are often good indicators of the severity of photochemical smog problems, many cities

in the U.S. and now worldwide issue smog alerts when ozone levels reach certain

plateaus. Smog alert levels exist for pollutants aside from ozone as well. Table 8.3

INTERNATIONAL REGULATION OF URBAN SMOG SINCE THE 1940s 219

identifies the mixing ratios of ozone, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide required

to trigger a California standard violation, a federal standard violation, a California

health advisory, and a California Stage 1, 2, and 3 smog alert.

Smog alerts in Los Angeles have been in place since the 1950s. Ozone levels

required for a Stage 1, 2, or 3 alert are based on the relative health risk associated with

each level. When an ozone smog alert occurs, individuals are advised to limit outdoor

activity to morning or early evening hours because ozone levels peak in the mid-

afternoon. Outdoor activities in schools are usually eliminated during a smog alert.

Health advisories for ozone were initiated in California in 1990 by the California Air

Resources Board because evidence indicated that ozone levels above the federal stan-

dard and below a Stage 1 smog alert may affect healthy, exercising adults. When a

health advisory occurs, all individuals, including children and healthy adults, are

advised to limit prolonged and vigorous outdoor exercise. Individuals with heart or lung

disease are advised to avoid outdoor activity until the advisory is no longer in effect.

8.1.12. U.S. Air Quality Trends from the 1970s

to Present

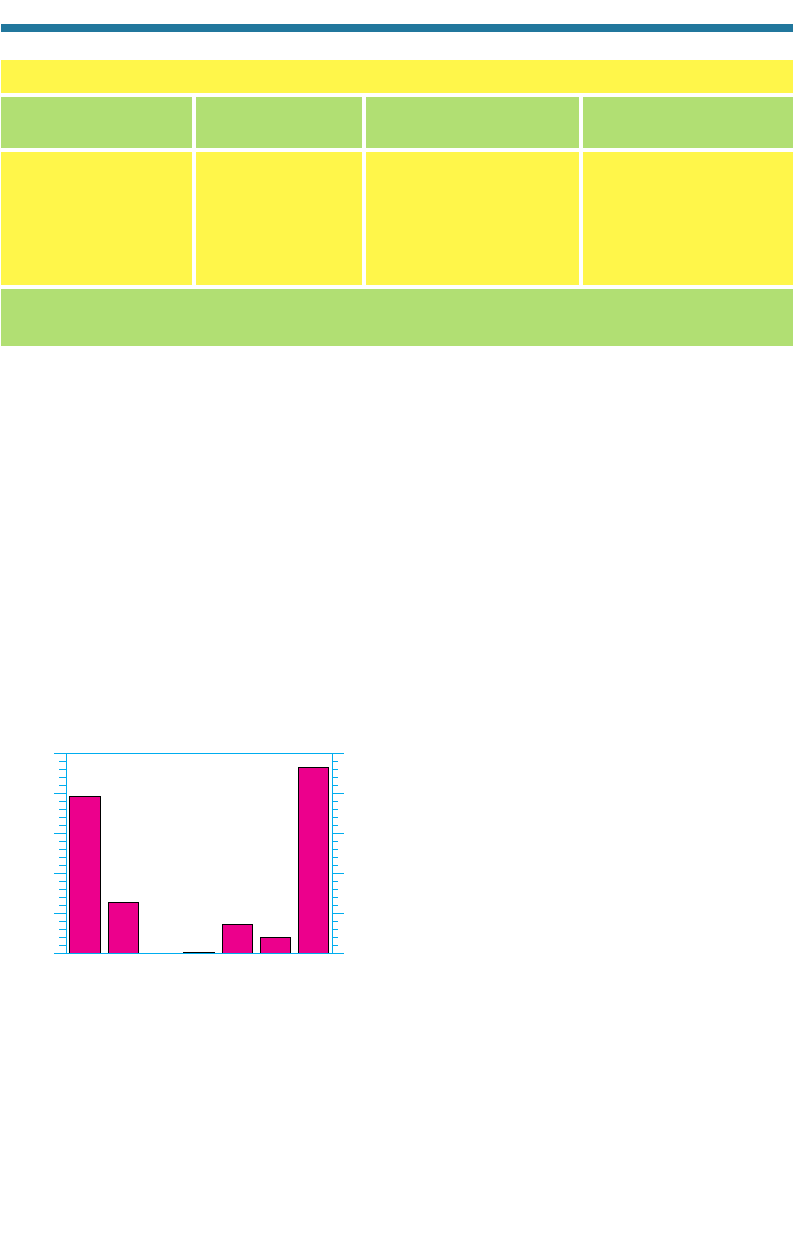

In 1996, more than 46 million people lived in areas of

the United States in which at least one NAAQS was

violated, as shown in Fig. 8.1. Most people exposed

to high pollutant levels were exposed to ozone.

The U.S. districts in which air quality problems

exist are in southern and central California, the

Boston through Washington (BoWash) corridor, the

Milwaukee through Chicago Great Lakes Region,

Phoenix, El Paso, Dallas–Ft. Worth, Houston, Baton

Rouge, and Atlanta.

Although pollution levels are far from ideal in

the United States, (e.g., Fig. 8.1), they have

improved in many urban U.S. cities since the 1950s.

Much of the improvement can be attributed to regu-

lations arising at the district (AQCR), state, and federal levels. Arguably, the Los

Angeles Air Pollution Control District, formed in 1947 and now called the South

Coast Air Quality Management District, has been at the forefront in initiating

regulations that were ultimately adopted at the federal level. Improvements in air

220 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Table 8.3. Mixing Ratios Required before the Given 1-Hour Standard Is Exceeded

California standard 0.09 20 0.25

Federal standard (NAAQS) 0.12

a

35 —

Health advisory 0.15

b

——

Stage 1 smog alert 0.20

b

40

b

0.60

b

Stage 2 smog alert 0.35

b

75

b

1.20

b

Stage 3 smog alert 0.50

b

100

b

1.60

b

Ozone 1-Hour Average Carbon Monoxide 1-Hour Nitrogen Dioxide 1-Hour

Health Standard Level Mixing Ratio (ppmv) Average Mixing Ratio (ppmv) Average Mixing Ratio (ppmv)

a

Prior to 1997.

b

Applies to California.

0

10

20

30

40

50

O

3

(g)

CO(g)

NO

2

(g)

SO

2

(g)

PM

10

Pb(s)

Any

Millions of people exposed

Pollutant

39.3

12.7

0 0.2

7.3

4.1

46.6

Figure 8.1. Number of people living in counties

exposed to pollutants above federal primary

air quality standards (NAAQS) in 1996.

Source: U.S. EPA Office of Air and Radiation.

California standard 0.09 20 0.25

Federal standard (NAAQS) 0.12

a

35 —

Health advisory 0.15

b

——

Stage 1 smog alert 0.20

b

40

b

0.60

b

Stage 2 smog alert 0.35

b

75

b

1.20

b

Stage 3 smog alert 0.50

b

100

b

1.60

b

a

Prior to 1997.

b

Applies to California.

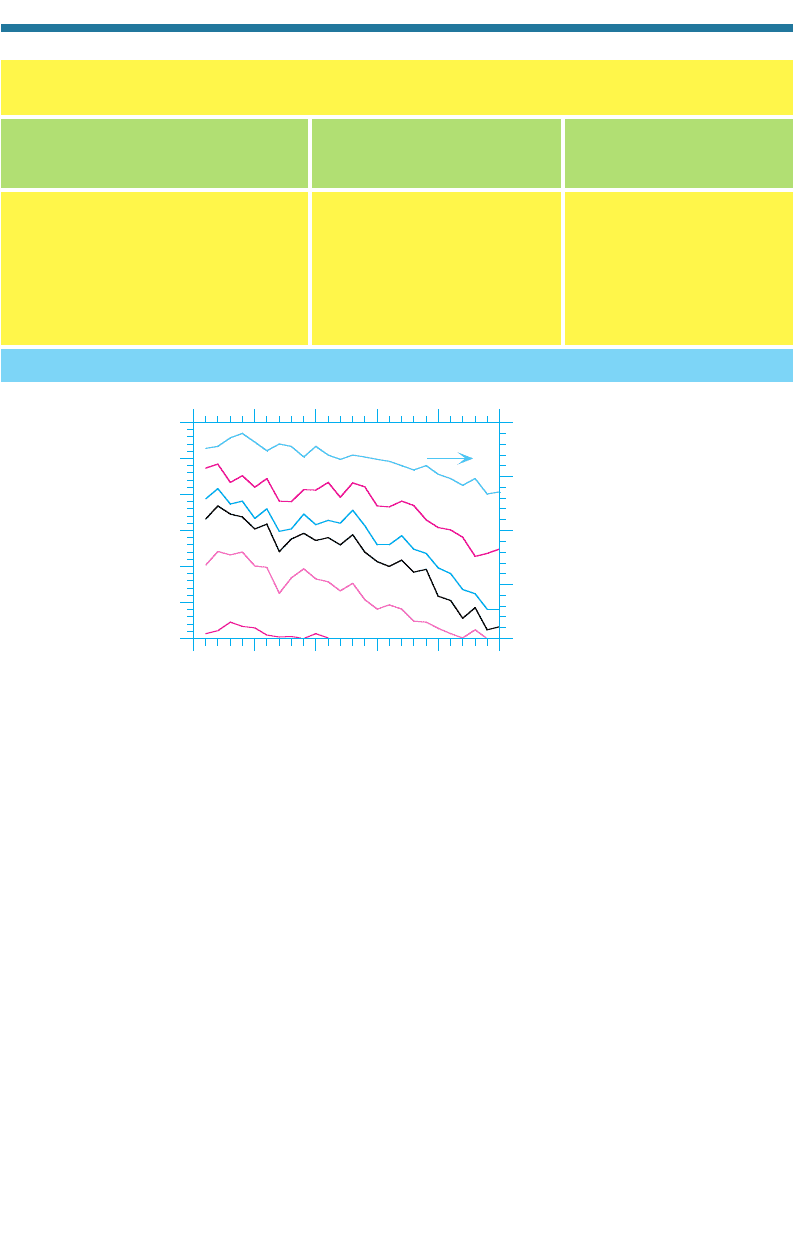

quality resulting from regulation are phenomenal,

particularly in Los Angeles. Figure

8.2 shows the number of days per year that state standards, federal standards, health

advisory levels, Stage 1 alerts, and Stage 2 alerts were exceeded between 1975 and

2000 in the Los Angeles Basin. The figure shows that the California state ozone stan-

dard, exceeded 237 days per year in 1976, was exceeded only 125 days per year in

2000. Between 1976 and 2000, NAAQS exceedences were reduced from 194 to 40

days per year, and Stage 2 and Stage 1 alerts were eliminated. Stage 3 alerts, frequent

in the 1950s, when peak ozone mixing ratios reached 0.68 ppmv, have not occurred in

Los Angeles since prior to 1976. Figure 8.2 shows that, between 1976 and 2000, the

highest ozone level recorded in the Los Angeles Basin was 0.45 ppmv (1979).

Nationwide, pollutant levels have likewise decreased since the late 1980s. Table

8.4 shows the percentage changes in (a) the number of federal primary standard excee-

dences and (b) emissions of criteria air pollutants and volatile organic compounds

between 1988 and 1997. The table indicates that the number of exceedences has

dropped for all criteria pollutants, and the number of emitted tons has decreased for all

pollutants shown, even though the number of automobiles and other pollutant sources

INTERNATIONAL REGULATION OF URBAN SMOG SINCE THE 1940s 221

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

0

0.25

0.5

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

Days of exceedences per year

Basin maximum (ppmv)

Year

State

Fed.

H.A.

Stage 1

Stage 2

Basin

maximum

Figure 8.2. Days per year that the ozone mixing ratio in the Los Angeles Basin exceeded the

California state standard (State), the NAAQS (Fed.), the California health advisory (H.A.) level,

the Stage 1 smog alert level, and the Stage 2 smog alert level from 1976 to 2000. Also

shown is the maximum ozone mixing ratio each year in the basin.

Source: South Coast Air Quality Management District.

Table 8.4. Percentage Changes in the Number of Federal Primary Standard (NAAQS) Exceedences

and Tons of Emissions in the United States from 1988 to 1997 for Several Pollutants

Ozone [O

3

(g)] 19 —

Carbon monoxide [CO(g)] 38 25

Nitrogen dioxide [NO

2

(g)] 14 1

Sulfur dioxide [SO

2

(g)] 39 12

Particulate matter 10m (PM

10

) 26 12

Lead [Pb(s)] 67 44

Reactive organic gases (ROGs) — 20

Percentage Change in Percentage Change

Number of NAAQS in Tons of

Pollutant Exceedences 1988–1997 Emissions 1988–1997

Source: U.S. EPA Office of Air and Radiation.

increased during this period. The U.S. EPA Office of Air and Radiation reports that

between 1970 and 1996, the U.S. population increased 29 percent, vehicle miles

traveled increased 121 percent, and gross domestic product increased 104 percent, but

total emissions of the six major emitted pollutants decreased 32 percent. The reason is

due to the widespread use of emission reduction technologies invented following

CAAA regulations of emissions and outdoor concentrations of air pollutants.

The improvement in air quality in the United States since 1970 and the correspon-

ding improvement in the economy attests to the fact that air pollution regulations do

not damage an economy. Instead, air pollution regulations lead to inventions and new

or expanded industries. Areas of invention include air pollution control technologies,

engine technologies, renewable energy technologies, and improved fuel technologies.

New or expanded industries include the renewable energy industries, the pollution

control device industry, the pollution measurement device industry, the pollution

remediation industry, the pollution software industry, and the pollution modeling

industry. Regulations have also resulted in the employment of public- and education-

al-sector workers in the area of pollution/climate regulation, policy, science, and

engineering and have led to the expansion of the supercomputer industry to satiate the

demand for the researchers devoted to studying and mitigating air pollution and

climate problems.

One of the industries that has expanded as a result of air pollution regulation is the

renewable energy industry. Between 1988 and 1998, consumption of renewable energy

(hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, solar, and wind energy) in the United States

increased by 19.9 percent, compared with an increase in comsumption of fossil-fuel

energy (petroleum, natural gas, and coal) of 12.3 percent. During the same period,

consumption of nuclear energy, a non-air polluting energy (except in the case of a

radioactive leak), also increased by 26.5 percent. Although alternative energy con-

sumption has increased in the United States, it represented only 7.4 percent of total

consumption in 1998. Fossil fuels were the source of 85 percent of total energy con-

sumed (Fig. 8.3). Figures 8.4 to 8.6 show examples of renewable energy sources.

222 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Petroleum

Natural gas

Coal

Nuclear

Hydroelectric

Biomass

Geothermal

Solar

Wind

Percenta

ge of U.S. energy consumption (1998)

Source of energy

0.033%

0.079%

0.354%

3.24%

3.76%

7.59%

22.97%

23.17%

38.81%

Figure 8.3. Percentage U.S. energy consumption by source in 1998. Total consumption was

94.2 quadrillion Btu.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

INTERNATIONAL REGULATION OF URBAN SMOG SINCE THE 1940s 223

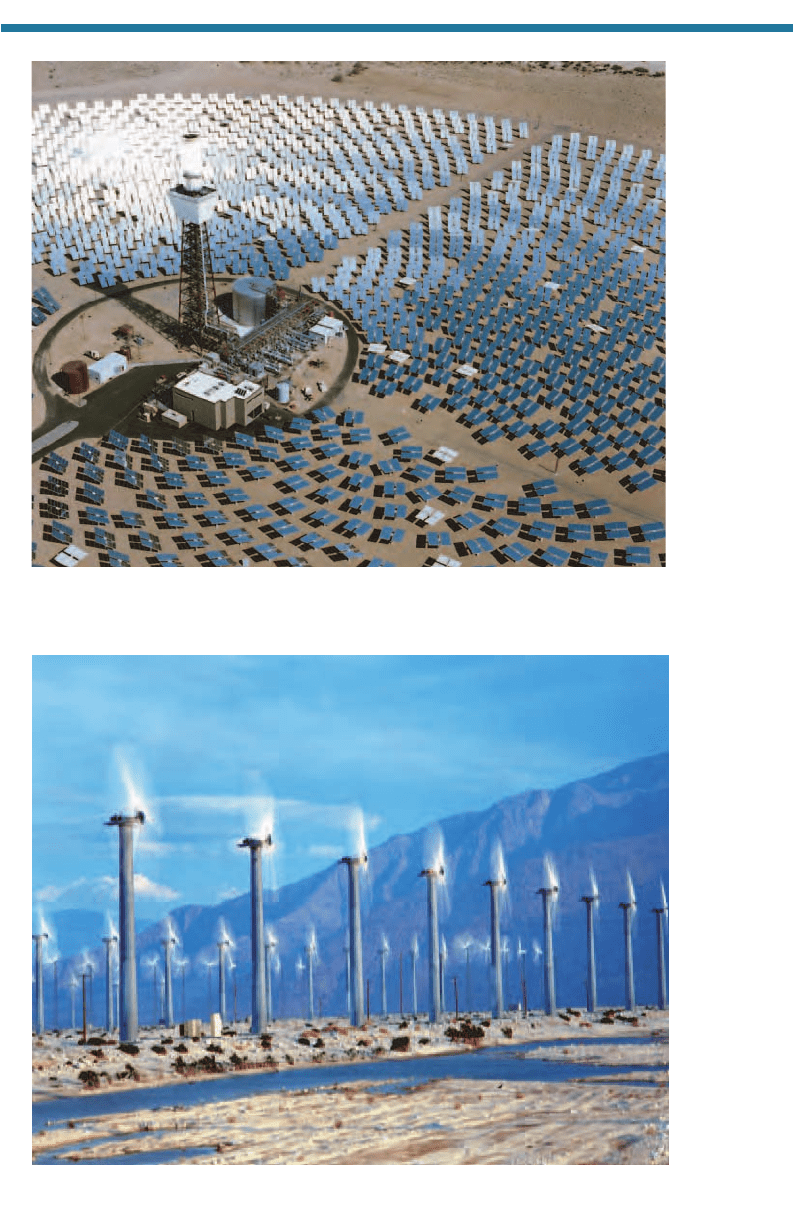

Figure 8.4. Reflectors focusing solar energy onto a 10-megawatt receiver power tower, called

Solar One, in Barstow, California. Photo by Sandia National Laboratory Staff, available from

the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Figure 8.5. Wind machines at dusk at a wind farm in Palm Springs, California. Photo by

Warren Gretz, available from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

8.1.13. Visibility Regulations and Trends

Currently, no U.S. national standard exists for visibility degradation. California first

set a visibility standard in 1959 and modified it in 1969. The 1969 standard required

that the prevailing visibility outside of Lake Tahoe exceed 10 miles (16.09 km) when

the relative humidity was less than 70 percent. In Lake Tahoe, the minimum allowable

visibility was set to 30 miles (48.3 km). Measurements were made by a person looking

224 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

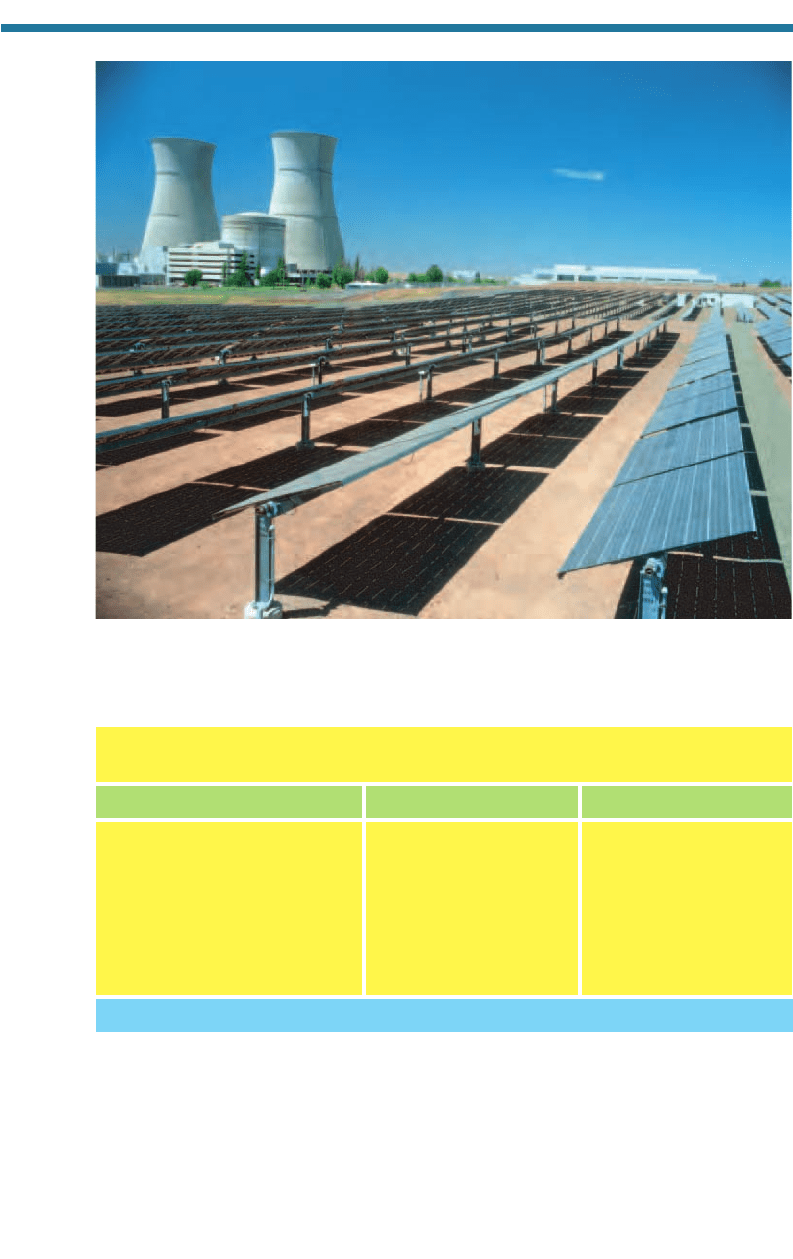

Figure 8.6. Solar photovoltaic system colocated with a nuclear power plant at the Sacramento

Municipal Utility District’s Rancho Seco facility. The photovoltaic system (2 megawatts),

spread over 8,094 m

2

, produces power for 660 homes. Photo by Warren Gretz, available from

the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Table 8.5. Number of Days per Year That California State Visibility Standard

Was Exceeded

Azusa No data 91

Burbank 180 No data

Lancaster 14 No data

Long Beach 155 No data

Los Angeles 154 No data

Ontario 250 No data

Riverside 200 No data

San Bernardino 200 176

Location 1990 1994

Source: South Coast Air Quality Management District.

for landmarks a known distance away. The furthest landmark that could be seen along

180º or more of the horizon circle defined the prevailing visibility.

Because prevailing visibility is a subjective measure of visibility, the California Air

Resources Board changed the California visibility standard in 1991 to one based on the use

of the meteorological range. The new standard required that the meteorological range at a

wavelength of 0.55 m not be less than 10 miles (16.09 km) outside of Lake Tahoe and 30

miles (48.3 km) in Lake Tahoe when the relative humidity was less than 70 percent.

Table 8.5 shows the number of days per year that the visibility standard was

exceeded at different locations in Los Angeles in 1990 and 1994. The 1990 data were

based on the prevailing visibility standard and the 1994 data were based on the mete-

orological range standard. The data indicate that in the eastern Los

Angeles Basin,

visibility was less than the state limit on 50 percent or more of the days of the year in

1990 and 1994. Such visibility degradation was due primarily to aerosol particle

buildup in the eastern basin.

Although no visibility regulations exist on a national level, prevailing visibility data

have been collected at 280 monitoring stations at airports in the United States since

1960. These data have been used primarily for air-traffic control purposes. Statistical

analysis of the data by the U.S. EPA Office of Air and Radiation indicate that visibility

deteriorated in the eastern United States between 1970 and 1980, but improved slightly

between 1980 and 1990. Visibility changes during these two decades correlate with

similar trends in emissions of sulfur dioxide. Table 8.6 shows an estimated percentage

contribution to visibility reduction in the western and eastern United States due to dif-

ferent pollutants. The largest contributor to visibility impairment in the east and west

was sulfates. Visibility impairment in the east was generally worse than that in the west

because higher relative humidities in the east resulted in aerosol particles with higher

liquid water contents and greater size than in the west. Figure 7.22 showed maps of

summer versus winter visibility in the United States between 1991 and 1995.

8.2. POLLUTION TRENDS AND REGULATIONS OUTSIDE

THE UNITED STATES

Whereas the United States has made an effort to reduce urban smog since 1955, other

countries have also made efforts, some over a period of decades and others over a peri-

od of a few years. In the 1950s, Los Angeles, California, may have been the most

polluted city in the world in terms of ozone, and London may have been the most

polluted in terms of particulates. Today, Mexico City, New Delhi, Beijing, Cairo, Sao

INTERNATIONAL REGULATION OF URBAN SMOG SINCE THE 1940s 225

Table 8.6. Percentage Contributions to Visibility Reduction in the Western and

Eastern United States as a Result of Different Aerosol Particle Components

Sulfates 25–65 60

Organic matter 15–35 10–15

Nitrates 5–45 10–15

Black carbon 15–25 10–15

Soil dust 10–20 10–15

Substance West East

Source: U.S. EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards.

Paolo, Shanghai, Jakarta, Bangkok, Tehran, and Calcutta are among the most polluted.

The World Health Organization (WHO) calculates that twelve of the fifteen cities with

the highest particulate levels and six of the fifteen cities with the highest sulfur dioxide

levels are in Asia. The WHO also calculates that about 2.7 million people die each year

from air pollution: 900,000 in cities and 1.8 million in rural areas. The largest source of

mortality from air pollution is indoor burning of biomass and coal (WHO, 2000).

Whereas health problems from lead have declined in the United States, western Europe,

and Japan, they have increased in many other countries. Lead levels found in children in

Cairo, Jakarta, Mexico City, and many cities in Africa and China are still high. In this

section, air quality trends and regulations in several countries are discussed.

8.2.1. Canada

Canadian air today is relatively clean in comparison with that in many other countries.

Canada’s yearly averaged concentrations of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and par-

ticulates are less than standards for these pollutants set by the

WHO. Nevertheless,

pollution is still a problem in many Canadian cities, and acid deposition affects its

lakes and forests.

Vehicles are the largest source of air pollution in Canada, responsible for 60 per-

cent of emissions. An increase in emissions of approximately 45 percent since 1990 is

attributable to an increase in the number of vehicles, particularly sport utility vehicles

(SUVs). Although emission controls have improved in vehicles during the same peri-

od, they have not compensated for the increase in SUV sales (EIA, 2000).

Canada has been concerned with air pollution since at least the late 1960s. In 1969,

it initiated an air pollution monitoring network called the National Air Pollution

Surveillance Network (NAPS).

This network contains nearly 240 air quality monitoring

stations, located mostly in urban areas. More recently, in 1999, Canada enacted a new

Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), under which the government obtained

new powers to control emissions, particularly of toxic substances. PM

10

was declared

toxic, allowing it to be regulated under the act. The act reduced the allowable level of

sulfur in gasoline and diesel, reduced the allowable level of benzene in gasoline, and

doubled funding for outdoor air pollution monitoring (Environment Canada, 2000a).

Ontario is the most polluted province in Canada. Environment Canada, the

Canadian national environmental agency, ordered refineries in Ontario to reduce sulfur

dioxide emissions by 2005. The government of Ontario also requires the measurement

of all harmful emissions from power plants.

A long-term goal of the Canadian government is to implement a Canada-wide 65

ppbv ozone standard by 2010. To obtain this goal, Canadians must reduce NO

x

(g) and

VOC emissions by about 35 percent by 2010. Canada also plans to increase reliance

on renewable energy sources. In 1998, about 29 percent of its electricity came from

hydroelectric power. The government intends to increase this source by 2 percent in

the coming years (EIA, 2000).

8.2.2. Mexico

In the 1940s, Mexico City’s air was relatively clean. Since 1940, its human population has

grown from 1.8 million to 20 million (making it the most populated city in the world), its

vehicle population has increased from tens of thousands to 3.5 million, and its factory

population has skyrocketed. Today, Mexico City’s air is among the dirtiest in the world.

226 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Like Los Angeles, Mexico City sits in a basin surrounded by mountains, and pollu-

tion is frequently trapped beneath the Pacific high-pressure system. Unlike Los

Angeles, Mexico City is not bounded by an ocean on one side.

Air pollution regulations in Mexico City were first enacted in 1971, with a Decree

to Prevent and Control Environmental Pollution, under which monitors were to be set

up to measure outdoor pollutant mixing ratios. A full set of monitors was implemented

only by 1986, at which time ozone was found to be the main pollutant. Ambient stan-

dards were then set for ozone, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, total

suspended particulates, and lead. In 1986, low-leaded gasoline was introduced, but by

1996, 44 percent of gasoline sold was still leaded (EIA, 2000). Other steps the govern-

ment took to reduce pollution were to provide incentives to relocate industry out of

Mexico City (1978) and to require vehicle inspections (1989).

In 1989, Mexico City enacted a program by which only cars with odd-numbered

license plates could be driven on a given day and cars with even-numbered plates

could be driven on the next. The program did not reduce pollution because many peo-

ple violated its spirit by switching license plates or cars. In other cases,

trips were

postponed by a day, but not canceled. More recently, a system was enacted that allows

only cars and trucks that use alternative fuels to be used seven days a week.

Ozone levels in Mexico City exceeded national standards 324 days in 1995. Also in

1995, Mexico initiated a five-year National Environmental Program (1996–2000)

designed to spend $13.3 million to clean up air pollution in Me

xico City. The government

also passed a tax-incentive program for the purchase of pollution-control equipment.

Although Mexico City was named by the World Resources Institute as the most

dangerous city in the world for children in terms of air pollution in 1999, the pollution

that year was the city’s lowest in a decade. Still, in August 2000, a smog event

required factories to shut down and students to stay indoors.

8.2.3. Brazil

Most of Brazil is covered with the Amazon rainforest, which makes up 30 percent of

the world’s remaining tropical forests. Sao Paolo, the capital of Brazil, is the second-

most populated city in the world after Mexico City. Air pollution in Sao Paolo results

from a large number of high-emitting automobiles, poor road systems, and low fuel

prices. Road-construction and railway projects in the city are expected to alleviate traf-

fic by 2002. Another city, Curitiba, was the fastest growing city in Brazil in the 1970s.

Curitiba has reduced its air pollution, despite population growth, by designing an effi-

cient road network and increasing the use of public transportation.

Brazil has an alcohol-fuel program, the Brazilian National Alcohol Program,

which was started in 1975 to reduce Brazil’s reliance on imported fuel following the

worldwide spike in oil prices in 1973. The program ensured that all gasoline sold in

Brazil contained 22 percent anhydrous ethanol and that the price of the ethanol–gasoline

blend would remain similar to that of gasoline alone. Ethanol for the project was pro-

duced primarily from sugarcane. Because the market price of an ethanol–gasoline

blend was higher than that of pure gasoline, the program required government subsi-

dies. When gasoline prices fell and sugarcane prices increased in the late 1980s,

ethanol prices rose sharply, and the program disintegrated. In 1997, only 1 percent of

new cars sold in Brazil used ethanol. Nevertheless, 41 percent of Brazil’s vehicles still

run on ethanol. In 1999, the Brazilian government revived the alcohol-fuel program by

encouraging the replacement of taxis and government vehicles with new vehicles that

INTERNATIONAL REGULATION OF URBAN SMOG SINCE THE 1940s 227