Jacobson M.Z. Atmospheric Pollution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

usually lower in the boundary layer of a low-pressure system than in that of a high-

pressure system.

6.7. EFFECTS OF LOCAL METEOROLOGY ON AIR POLLUTION

Whereas large-scale pressure systems control the prevailing meteorology of a region,

local factors also affect meteorology and, thus, air pollution. Some of these factors are

discussed briefly.

6.7.1. Ground Temperatures

Ground temperatures affect local meteorology and air pollution in at least three w

ays.

Figure 6.14 gives insight into the first mechanism. The figure shows that warm ground

surfaces produce high inversion base heights (thick mixing depths) and low pollution

mixing ratios. Conversely, cold ground surfaces produce thin mixing depths and high

pollution mixing ratios.

A second mechanism by which ground temperatures affect pollution is through

their effects on wind speeds. Warm surfaces enhance convection, causing surface air to

mix with air aloft and vice-versa. Because horizontal wind speeds at the ground are

zero and those aloft are faster, the vertical mixing of horizontal winds speeds up winds

near the surface and slows them down aloft. Faster near-surface winds result in greater

dispersion of near-surface pollutants but may also increase the resuspension of loose

soil dust and other aerosol particles from the ground. Cooler ground temperatures

have the opposite effect, slowing down near-surface winds and enhancing near-surface

pollution buildup.

Third, changes in ground temperatures change near-surface air temperatures, and

air temperatures affect rates of several processes. For example, rates of biogenic gas

emissions from trees, carbon monoxide emissions from vehicles, chemical reactions,

and gas-to-particle conversion are all temperature-dependent.

6.7.2. Soil Liquid Water Content

An important parameter that affects ground temperatures, and therefore pollutant con-

centrations, is soil liquid water. Increases in soil liquid water cool the ground, reducing

convection, decreasing mixing depths, and slo

wing near-surface winds. Thinner mix-

ing depths and slower winds enhance pollutant buildup. Conversely, decreases in soil

liquid water increase convection, increasing mixing depths and speeding near-surface

winds, reducing pollution.

Soil water cools the ground in two major ways. First, evaporation of liquid water in

soil cools the soil. Therefore, the more liquid water a soil has, the greater the evapora-

tion and cooling of the soil during the day. Second, liquid water in soil increases the

average specific heat of a soil–air–water mixture. The wetter the soil, the less the soil

can heat up when solar radiation is added to it.

In a study of the effects of soil liquid water on temperatures, winds, and pollution,

it was found that increases in soil water of only 4 percent decreased peak near-surface

air temperatures by up to 6 C, decreased wind speeds by up to 1.5 m/s, delayed the

times of peak ozone mixing ratio by up to two hours, and increased the magnitude of

peak particulate concentrations substantially in Los Angeles over a two-day period

168 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

(Jacobson, 1999b). Such results imply that rainfall, irrigation, and climate change all

affect pollution concentrations.

6.7.3. Urban Heat Island Effect

Landcover affects ground temperature, which affects pollutant concentrations. Most of

the globe is covered with water (71.3 percent) or snow/ice (3.3 percent). The remainder is

covered with forests, grasslands, croplands, wetlands, barren lands, tundra, savanna,

shrubland, and urban areas. Urban surfaces consist primarily of roads, walkways,

rooftops, vegetation cover, and bare soil. Urban construction material surfaces increase

surface temperatures due to the urban heat island effect, first recorded in 1807 by

English meteorologist Luke Howard (1772–1864) (also known for classifying clouds).

Howard measured temperatures at several sites within and outside London and found that

temperatures within the city were consistently warmer than were those outside.

Figure 6.18 shows a satellite-derived image of daytime surface temperatures in

downtown Atlanta and its en

virons. Road surfaces and buildings stand out as being

particularly hot. Urban areas heat up during the day and night to a greater extent than

do surrounding vegetated areas because urban areas generally contain less liquid water

than do surrounding vegetated areas (Oke, 1988, 1999). When liquid water is absent,

evaporation rates and corresponding energy losses from the surface are slower than

when liquid water is present, warming surface temperatures.

Increased urban temperatures result in increased mixing depths, faster near-surface

winds, and lower near-surface concentrations of pollutants. Increased urban temperatures

may also be responsible for enhanced thunderstorm activity (Bornstein and Lin, 2000).

EFFECTS OF METEOROLOGY ON AIR POLLUTION 169

Figure 6.18. Landsat 5 satellite image with buildings superimposed showing daytime surface

temperatures in Atlanta, Georgia. Temperatures from hot to cold are represented by white,

red, yellow, green, and blue, respectively. Small cool areas in the middle of warm areas are

often due to shadows caused by large buildings.

6.7.4. Local Winds

Another factor that affects air pollution is the local wind. Winds arise due to pressure

gradients. Although large-scale pressure gradients affect winds, local pressure gradi-

ents, resulting from uneven ground heating, variable topography, and local turbulence,

can modify or override large-scale winds. Important local winds include sea, lake, bay,

land, valley, and mountain breezes.

6.7.4.1. Sea, Lake, and Bay Breezes

Sea, lake, and bay breezes form during the day between oceans, lakes, or bays,

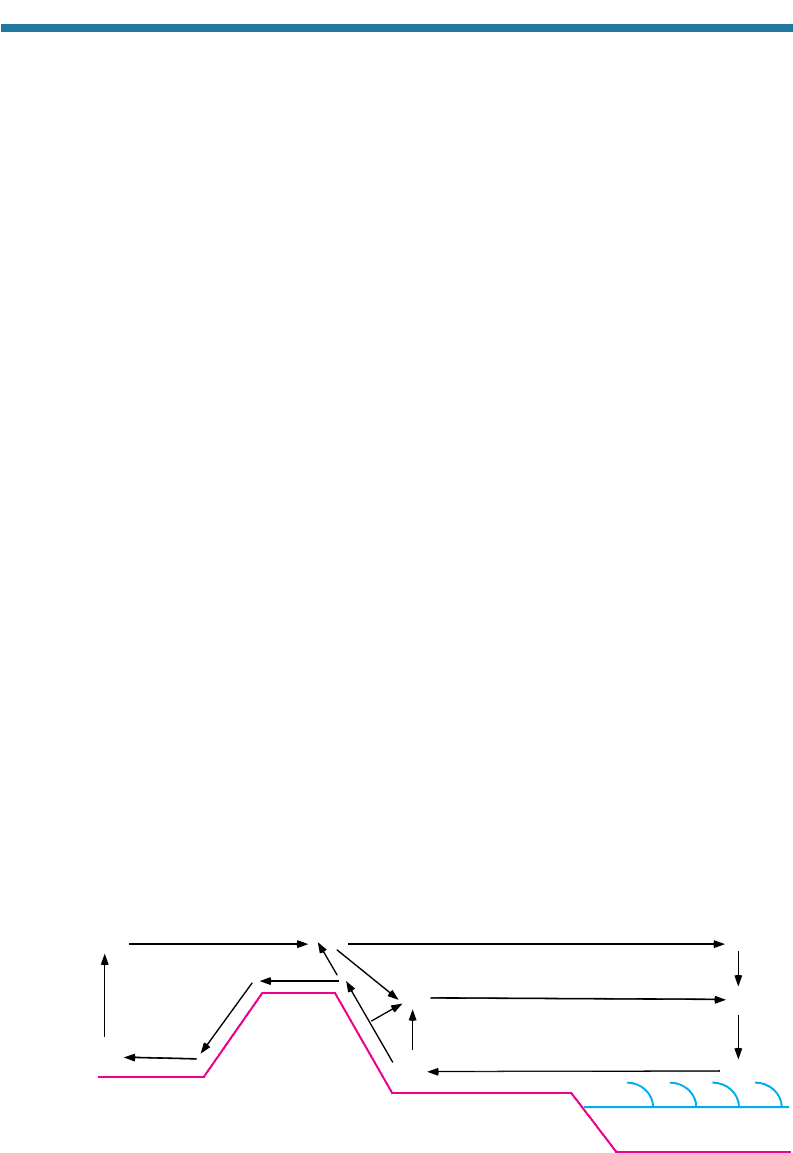

respectively, and land. Figure 6.19 illustrates a basic sea-breeze circulation. During the

day, land heats up relative to water because land has a lower specific heat than does

water. Rising air over land forces air aloft to diverge horizontally, decreasing surface-

air pressures (setting up a shallo

w thermal low-pressure system) over land. As a result

of the pressure gradient between land and water, air moves from the water, where the

pressure is now relatively high, toward the land. In the case of ocean water meeting

land, the movement of near-surface air is the sea breeze. Although the ACoF acts on

the sea-breeze air, the distance traveled by the sea-breeze is too short (a few tens of

kilometers) for the Coriolis force to turn the air noticeably

.

Meanwhile, some of the diverging air aloft over land returns toward the water. The

convergence of air aloft over water increases surface air pressure over water, prompt-

ing a stronger flow of surface air from the water to the land, completing the basic

sea-breeze circulation cell. At night, land cools to a greater extent than does water, and

all the pressures and flow directions in Fig. 6.19 reverse themselv

es, creating a

land

breeze, a near-surface flow of air from land to water.

Figure 6.19 illustrates that a basic sea-breeze circulation cell can be embedded in a

large-scale sea-breeze cell. The Los Angeles Basin, for example, is bordered on its

southwestern side by the Pacific Ocean and on its eastern side by the San Bernardino

Mountains. The Mojave Desert lies to the east of the mountains. The desert heats up

more than does land near the coast during the day, creating a thermal low over the desert,

drawing air in from the coast, creating the circulation pattern shown in the figure.

Figure 6.20 illustrates the variation of sea- and land-breeze wind speeds at

Hawthorne, California, near the coast in the Los

Angeles Basin, over a three-day

period. Sea-breeze wind speeds peak in the afternoon, when land–ocean temperature

170 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Desert

(hot)

Coast

(warm)

Ocean

(cold)

H

L

L

H

H

Basic sea-breeze cell

Large-scale sea-breeze cell

L

Mountain chimney effect: injection of pollutants to free troposphere

Elevated pollution layers

Valley breeze

Figure 6.19. Illustration of a large-scale sea-breeze circulation cell, basic sea-breeze circula-

tion cell, valley breeze, the chimney effect, and the formation of elevated pollution layers,

as described in the text. Pressures shown (L and H) are relative to other pressures in the

horizontal.

differences peak. Similarly, sea-breeze winds peak in summer and are minimum in

winter. Land breezes are relatively weak in comparison with sea breezes because at

night, the land–ocean temperature difference is small.

6.7.4.2. Valley and Mountain Breezes

A valley breeze is a wind that blows from a valley up a mountain slope and results

from the heating of the mountain slope during the day. Heating causes air on the

mountain slope to rise, drawing air up from the valley to replace the rising air

. Figure

6.19 illustrates that in the case of a mountain near the coast, a valley breeze can

become integrated into a large-scale sea-breeze cell. The opposite of a valley breeze is

a mountain breeze, which originates from a mountain slope and travels downward.

Mountain breezes typically occur at night, when mountain faces cool rapidly. As a

mountain face cools, air above the face also cools and drains downslope.

6.7.4.3. Effects of Sea and Valley Breezes on Pollution

In the Los Angeles Basin, sea and valley breezes are instrumental in transferring

primary pollutants, emitted mainly from source regions on the west side of the basin,

to receptor regions on the east side of the basin, where they arrive as secondary pollu-

tants. Figure 4.10 showed an example of the daily variation of NO(g), NO

2

(g), and

O

3

(g) at a source and receptor region in Los Angeles. The valley breeze, in particular,

moves ozone from Fontana, Riverside, and San Bernardino, in the eastern Los Angeles

Basin, up the San Bernardino Mountains to Crestline, one of the most polluted loca-

tions in the United States in terms of ozone.

6.7.4.4. Chimney Effect and Elevated Pollution Layers

Pollutants in an enclosed basin, such as the Los Angeles Basin, can escape the

basin through mountain passes and over mountain ridges. A third mechanism of

escape is through the mountain chimney effect (Lu and Turco, 1995). Through this

effect, a mountain slope is heated, causing air containing pollutants to rise, injecting

the pollutants from within the mixed layer into the free troposphere. The mountain

chimney effect is illustrated in Fig. 6.19.

Instead of dispersing, gases and particles may build up in elevated pollution

layers. Pollutant concentrations in these layers often exceed those near the ground.

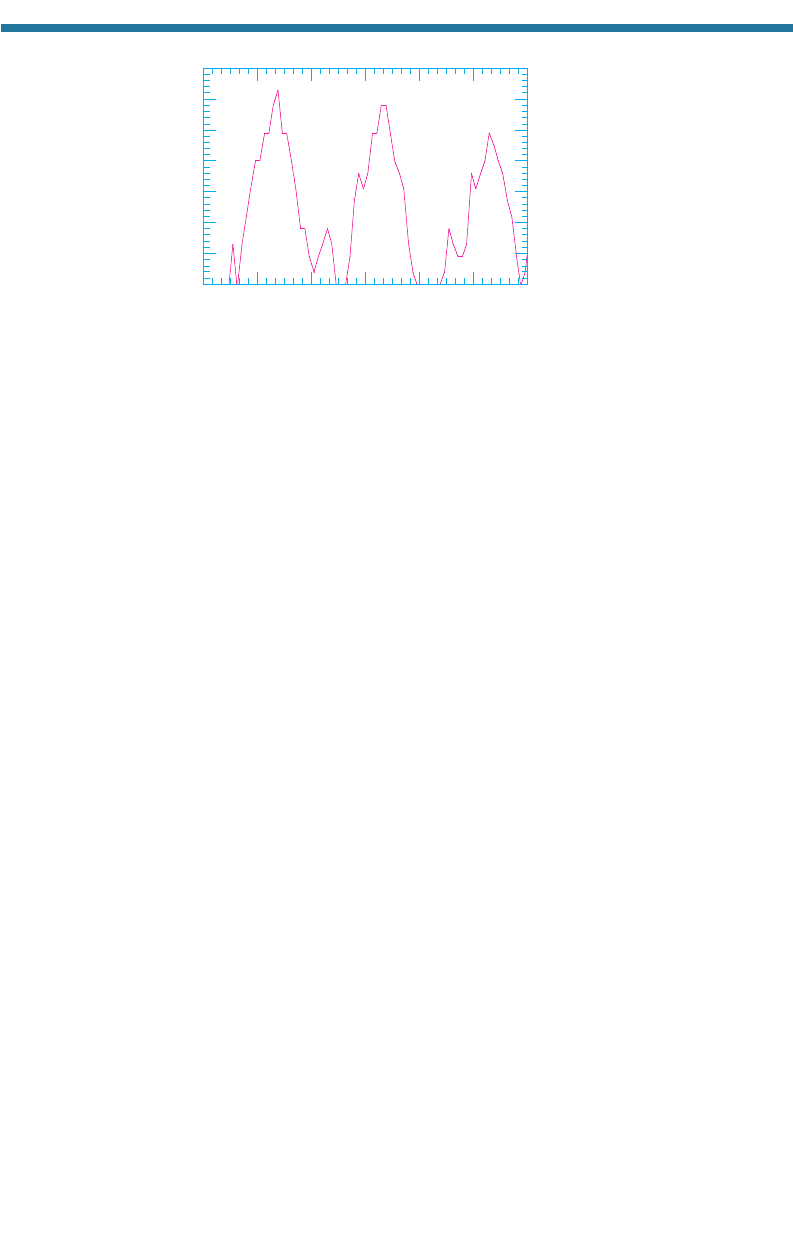

Fig. 6.21 shows a brilliant sunset through an elevated pollution layer in Los Angeles.

Elevated layers form in one of at least four ways.

EFFECTS OF METEOROLOGY ON AIR POLLUTION 171

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0 122436486072

Wind speed (m/s)

Hour of day

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Figure 6.20. Wind speeds at Hawthorne, California, August 26–28, 1987.

172 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Figure 6.22. Elevated pollution layer formed over Long Beach, California, on July 22, 2000, by

a sea-breeze circulation.

Figure 6.21. Brilliant sunset through elevated pollution layer over Los Angeles, California, May

1972. Photo by Gene Daniels, U.S. EPA, available from the Still Pictures Branch, U.S.

National Archives.

EFFECTS OF METEOROLOGY ON AIR POLLUTION 173

First, sea-breeze circulations themselves can

form elevated layers by lifting and injecting polluted

air into the in

version layer during its return

flow

to the ocean. Elevated pollution layers formed by

this mechanism have been reported in Tokyo

(Wakamatsu et al., 1983), Athens (Lalas et al.,

1983), and near Lake Michigan (Fitzner et al., 1989;

Lyons et al., 1991). Figure 6.22 shows an example

of an elevated pollution layer caused by a sea-breeze

circulation over Long Beach, California.

Second, some of the air forced up a mountain

slope by winds may rise into and spread horizontally

in an inversion layer. Of the air that continues up the

mountain slope past the inversion, some may circu-

late back down into the inversion (Lu and Turco,

1995). Elevated pollution layers formed by this

mechanism have been observed adjacent to the San

Bernardino and San Gabriel Mountain Ranges in

Los Angeles (Wakimoto and McElroy, 1986).

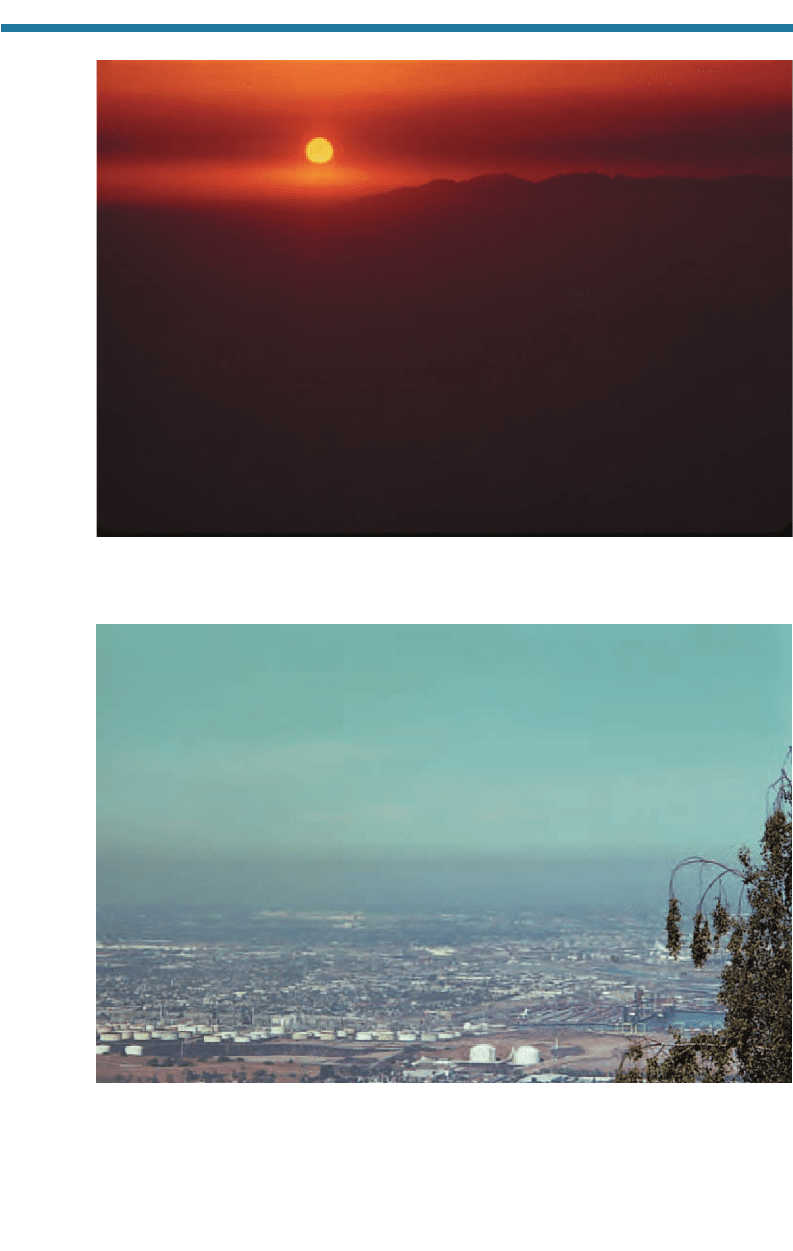

Third, emissions from a smokestack or fire can

rise buoyantly into an inversion layer. The inversion

limits the height to which the plume can rise and

forces the plume to spread horizontally. Figure 6.23 shows an example of a pollution

layer formed by this mechanism.

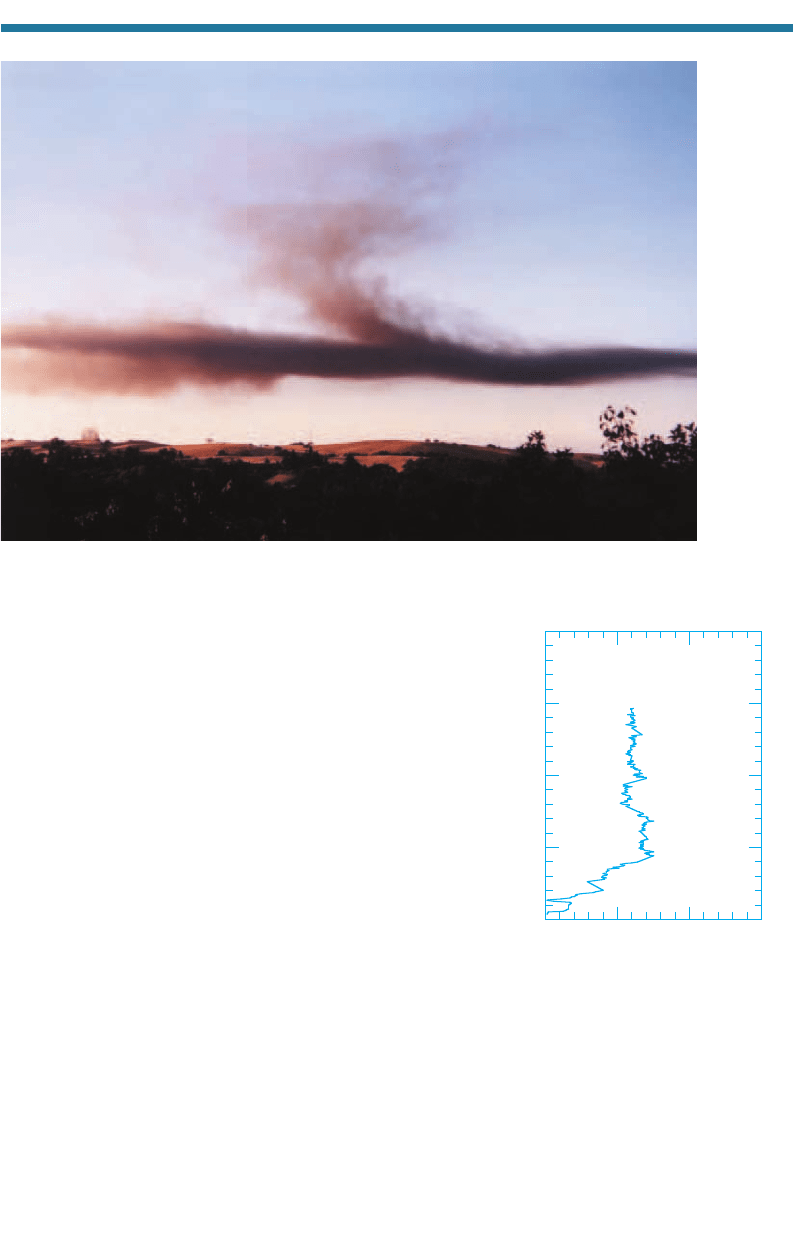

Fourth, elevated ozone layers in the boundary layer may form by the destruction of

surface ozone. During the afternoon, ozone dilutes uniformly throughout a mixing depth.

Figure 6.23. Elevated layer of smoke trapped in an inversion layer following a greenhouse fire

in Menlo P

ark, California in June 2001.

0 0.05 0.1 0.15

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

Ozone mixing ratio (ppmv)

Altitude above sea level (m)

Aircraft

spiral

-121.24W

37.89N

8/06/90

05:08 PST

Figure 6.24. Vertical profile of ozone mixing

ratio over Stockton, California, on August 6,

1990, at 05:08 Pacific Standard Time (PST)

showing a nighttime elevated ozone layer that

formed by the destruction of surface ozone.

Data from the SARMAP field campaign (see

Solomon and Thuillier, 1995).

In the evening, cooling of the ground stabilizes the air near the surface without affecting

the stability aloft. In regions of nighttime NO(g) emissions, the NO(g) destroys near-

surface ozone. Because nighttime air near the surface is stable, ozone aloft does not mix

downward to replenish the lost surface ozone. Figure 6.24 shows an example of an ele-

vated ozone layer formed by this process. The next

day, the mixing depth increases, recapturing the ele-

vated ozone and mixing it downward. McElroy and

Smith (1992) estimated that daytime downmixing of

elevated ozone enhanced surface ozone in certain

areas of Los Angeles by 30 to 40 ppbv above what

they would otherwise have been due to photochem-

istry alone. When few nighttime sources of NO(g)

exist, elevated ozone layers do not form by this

mechanism.

6.7.5. Plume Dispersion

Another effect of local meteorology on air pollution

is the effect of stability on plume dispersion from

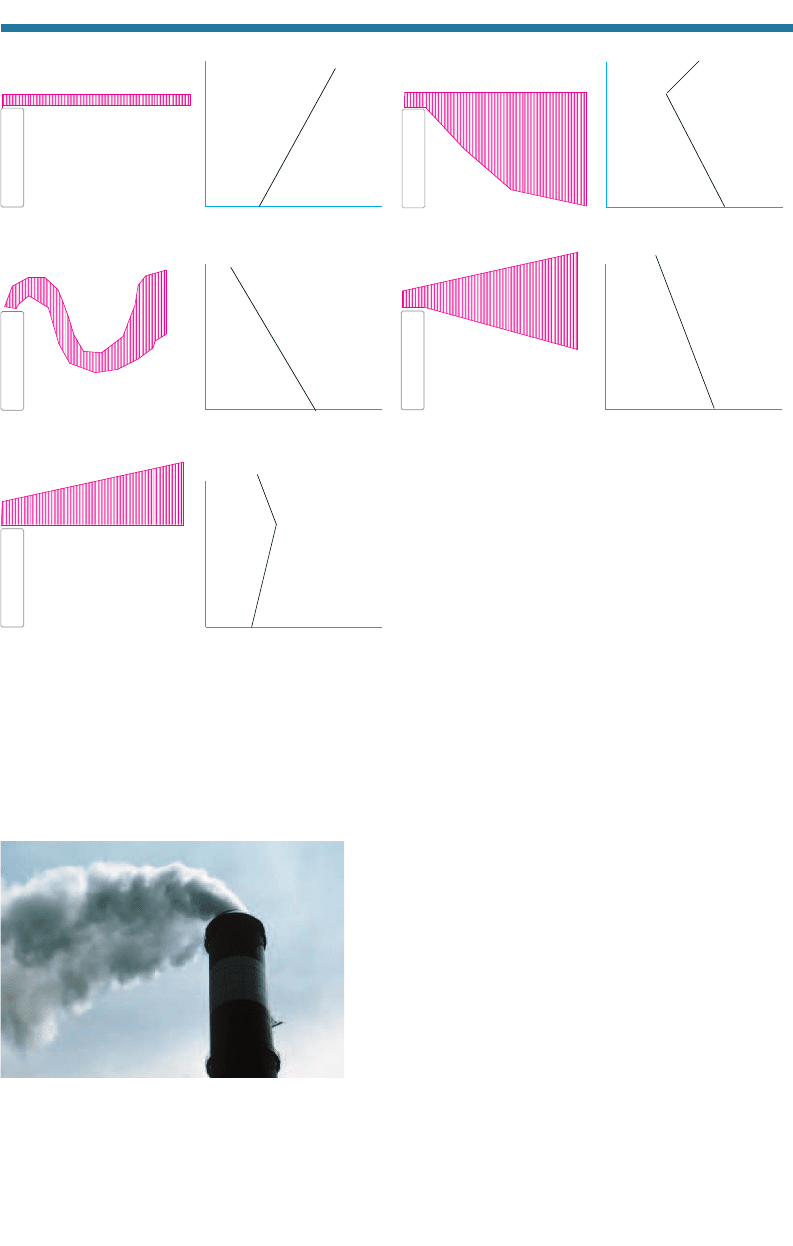

smokestacks. Figure 6.25 illustrates cross-sections of classic plume configurations that

result from different stability conditions. In stable air, pollutants emitted from stacks do

not rise or sink vertically; instead, they fan out horizontally. Viewed from above, the

174 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

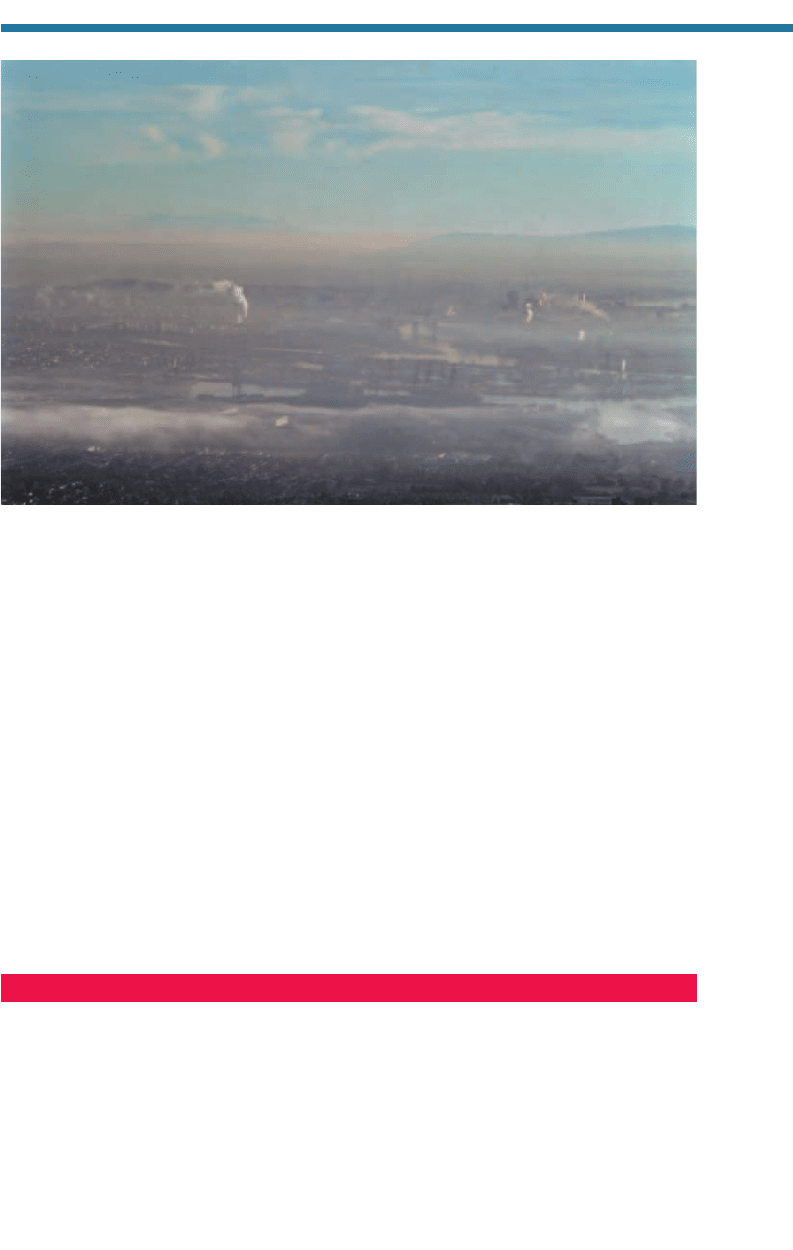

Figure 6.26. Lofting of pollution from a power

plant using coal to generate electricity. Photo by

National Renewable Energy Laboratory Staff.

Stable

Γ

e

Fanning

Temperature Temperature

Stable

Γ

e

Neutral or

Unstable

Fumigating

Temperature

Unstable

Γ

e

Looping

Temperature

Neutral

Γ

e

Coning

Temperature

Neutral

Γ

e

Stable

Lofting

Figure 6.25. Cross-sections of plumes under different stability conditions.

pollution distribution looks like a giant fan. Fanning does not expose people to pollution

immediately downwind of a stack because the fanned pollution does not mix down to

the surface. Figure 6.23 shows the side view of a fanning plume originating from a fire,

not a stack. The worst meteorologic condition for those living immediately downwind

of a stack occurs when the atmosphere is neutral or unstable below the stack and stable

above. This condition leads to fumigation, or the downwashing of pollutants toward the

surface. Looping occurs when the atmosphere is unstable. Under such a condition,

emissions from a stack may alternately rise and sink, depending on the extent of turbu-

lence. Coning occurs when the atmosphere is neutrally stratified. Under such a

condition, pollutants emitted tend to slowly disperse both upward and downward. When

the atmosphere is stable below and neutral above a stack, lofting occurs. Lofting results

in the least potential exposure to pollutants by people immediately downwind of a stack.

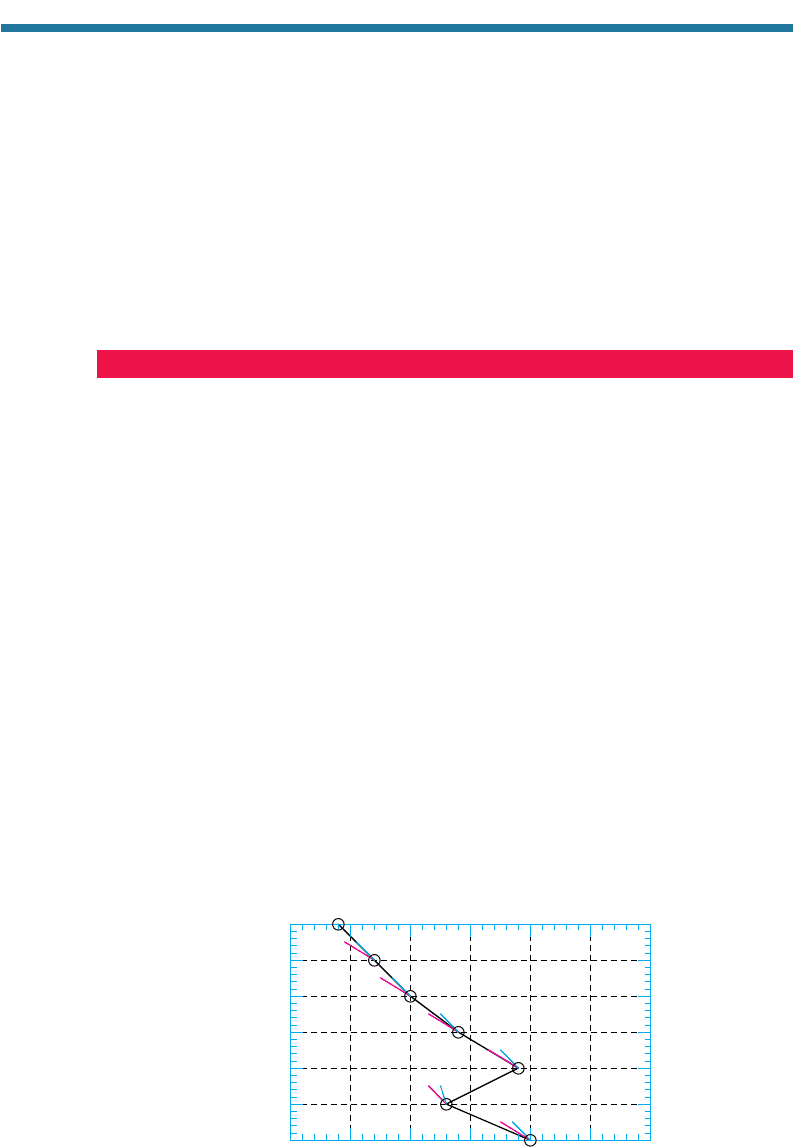

Figure 6.26 shows an example of lofting from a smokestack. Figure 6.27 shows several

plumes lofting into an inversion layer in the Los Angeles Basin.

6.8. SUMMARY

In this chapter, the forces acting on winds, the general circulation of the atmosphere,

the generation of large-scale pressure systems, the effects of large-scale pressure

systems on air pollution, and the effects of small-scale weather systems on air pollu-

tion were discussed. Forces examined include the pressure gradient force, apparent

Coriolis force, apparent centrifugal force, and friction forces. The winds produced by

these forces include the geostrophic wind, the gradient wind, and surface winds. On

the global scale, the south–north and vertical components of wind flow can be

described by three circulation cells – the Hadley, Ferrel, and Polar cells – in each the

Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Descending and rising air in the cells result in

EFFECTS OF METEOROLOGY ON AIR POLLUTION 175

Figure 6.27. Plumes rising into an inversion layer in Long Beach, California, on December

19, 2000.

the creation of large-scale semipermanent high-and low-pressure systems over the

oceans. Pressure systems over continents (thermal pressure systems) are seasonal and

controlled by ground heating and cooling. Large-scale pressure systems affect

pollution through their effects on stability and winds. Surface high-pressure systems

enhance the stability of the boundary layer and increase pollution buildup. Surface

low-pressure systems reduce the stability of the boundary layer and decrease pollution

buildup. Soil moisture affects stability, winds, and pollutant concentrations. Sea and

valley breezes are important local-scale winds that enhance or clear out pollution in an

area. Elevated pollution layers, often observed, are a product of the interaction of

winds, stability, topography, and chemistry.

6.9. PROBLEMS

6.1. Draw a diagram showing the forces and the gradient wind around an elevated

low-pressure center in the Southern Hemisphere.

6.2. Draw a diagram showing the forces and resulting winds around a surface low-

pressure center in the Southern Hemisphere.

6.3. Should horizontal winds turn clockwise or counterclockwise with increasing

height in the Southern Hemisphere? Demonstrate your conclusion with a force

diagram at the surface and aloft.

6.4. Characterize the stability of each of the six layers in Fig. 6.28 with one of the

stability criteria given in Equation 6.4.

6.5. If the Earth did not rotate, how would you expect the current three-cell model

of the general circulation of the atmosphere to change?

6.6. In Fig. 6.28, to approximately what altitude will a parcel of pollution rise adia-

batically from the surface in unsaturated air if the parcel’s initial temperature is

25 C? What if its initial temperature is 30 C?

176 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

6

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Altitude (km)

Temperature (°C)

Γ

e

Γ

d

Γ

w

Layer 1

Layer 2

Layer 3

Layer 4

Layer 5

Layer

Figure 6.28. Environmental temperature profile with wet and dry adiabatic lapse rate profiles

superimposed.

6.7. In Fig. 6.28, to approximately what altitude will a parcel of pollution rise adia-

batically from the surface in saturated air if the parcel’s initial temperature is

25 C? What if its initial temperature is 30 C? Assume a wet adiabatic lapse

rate of 6 C km

1

.

6.8. Why do ozone mixing ratios peak in the afternoon, even though mixing depths

are usually maximum in the afternoon?

6.9. Explain why ozone mixing ratios are higher on the east side of the Los Angeles

Basin, even though ozone precursors are emitted primarily on the west side of

the basin.

6.10.

Summarize the meteorologic conditions that tend to enhance and reduce,

respectively, photochemical smog buildup in an area.

6.11. If emissions did not change with season,

why might CO(g) and aerosol particle

concentrations be higher in winter than in summer?

6.12. If a diesel-engine truck is driving in front of you, and much of the exhaust is

entering your car and not rising in the air, how would you define the plume-

dispersion shape?

6.13. From Fig. 6.28, determine the following quantities:

(a) inversion base height

(b) inversion top height

(c) inversion base temperature

(d) inversion top temperature

(e) inversion strength

(f) inversion thickness

(g) mixing depth.

EFFECTS OF METEOROLOGY ON AIR POLLUTION 177