Iozzo Renato V. Proteoglycan Protocols

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

138 Turnbull

6. Because the emission wavelength is 410–420 nm, there is a need to filter out background

visible wavelength light from the UV lamps. This can be done effectively with special glass

filters that permit transmission of UV light but do not allow light of wavelengths >400 nm

to pass. A blue bandpass filter on the camera also improves sensitivity. Suitable filters are

available from HV Skan (Stratford Road, Solihull, UK; Tel: 0121 733 3003) or UVItec

Ltd (St Johns Innovation Centre, Cowley Road, Cambridge, UK: www.uvitec.

demon.co.uk).

7. Required exposure times are strongly dependent on sample loading and the level of detec-

tion required. Overly long exposures will result in excessive background signal. Note that

negative images are usually better for band identification (see figures). Under the condi-

tions described, the limit of sensitivity is ~1–2 pmol/band (see Fig. 1), with ~5–10 pmol

being optimal. Recently it has been found that ~10-fold more sensitive detection is pos-

sible using an alternative fluorophore aminonaphthalenedisulfonic acid (21,22).

References

1. Spillmann, D. and Lindahl, U. (1994) Gycosaminoglycan-protein interactions: a question

of specificity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 4, 677–682.

2. Bernfield M., Gotte, M., Park, P. W., et al. Functions of Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate

Proteoglycans. Ann. Rev. Biochem. (1999) 68, 729–777.

3. Turnbull, J. E. and Gallagher, J. T. (1991) Distribution of Iduronate-2-sulfate residues in

HS: evidence for an ordered polymeric structure. Biochem. J. 273, 553–559.

4. Turnbull, J. E., Fernig, D., Ke, Y., Wilkinson, M. C., and Gallagher, J. T. (1992) Identifica-

tion of the basic FGF binding sequence in fibroblast HS. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 10,337–10,341.

5. Pervin, A., Gallo, C., Jandik, K., Han, X., and Linhardt, R., (1995) Preparation and struc-

tural characterisation of heparin-derived oligosaccharides. Glycobiology 5, 83–95.

6. Yamada, S., Yamane, Y., Tsude, H., Yoshida, K., and Sugahara, K. (1998) A major com-

mon trisulfated hexasaccharide isolated from the low sulfated irregular region of porcine

intestinal heparin. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 1863–1871.

7. Yamada, S., Yoshida, K., Sugiura, M., Sugahara, K., Khoo, K., Morris, H., and Dell, A. (1993)

Structural studies on the bacterial lyase-resistant tetrasaccharides derived from the antithrom-

bin binding site of porcine mucosal intestinal heparin. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4780–4787.

8. Mallis, L., Wang, H., Loganathan, D., and Linhardt, R. (1989) Sequence analysis of highly

sulfated heparin-derived oligosaccharides using FAB-MS. Anal. Chem. 61, 1453–1458.

9. Rhomberg A. J., Ernst, S., Sasisekharan, R., Biemann, K., et al. (1998) Mass spectromet-

ric and capillary electrophoretic investigation of the enzymatic degradation of heparin-

like glycosaminoglycans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 95, 4176–4181.

10. Hopwood, J. (1989) Enzymes that degrade heparin and heparan sulfate. In: Heparin (Lane

and Lindahl, eds.), Edward Arnold, London, UK, pp. 191–227.

11. Turnbull, J. E., Hopwood, J. J., and Gallagher, J. T. (1999) A strategy for rapid sequencing

of heparan sulfate/heparin saccharides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 96, 2698–2703.

12. Merry, C. L. R., Lyon, M., Deakin, J. A., Hopwood, J. J., and Gallagher, J. T. (1999)

Highly sensitive sequencing of the sulfated domains of heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem.

274, 18,455–18,462.

13. Vives, R. R., Pye, D. A., Samivirta, M., Hopwood, J. J., Lindahl, U., and Gallagher, J. T.

(1999) Sequence analysis of heparan sulphate and heparin oligosaccharides. Biochem. J.

339, 767–773.

14. Venkataraman, G., Shriver, Z., Raman, R., Sasisekharan, R., et al. (1999) Sequencing

complex polysaccharides. Science 286, 537–542.

Glycan Sequencing of HS and Heparin Saccharides 139

15. Guimond, S. E. and Turnbull, J. E. (1999) Fibroblast growth factor receptor signalling is

dictated by specific heparan sulfate saccharides. Curr. Biol. 9, 1343–1346.

16. Shively, J. and Conrad, H. (1976) Formation of anhydrosugars in the chemical

depolymerisation of heparin. Biochemistry 15, 3932–3942.

17. Bienkowski, M. J. and Conrad, H. E. (1985) Structural characterisation of the oligosaccha-

rides formed by depolymerisation of heparin with nitrous acid. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 356–365.

18. Turnbull, J. E. and Gallagher, J. T. (1988) Oligosaccharide mapping of heparan sulfate by

polyacrylamide-gradient-gel electrophoresis and electrotransfer to nylon membrane.

Biochem J 251, 597–608.

19. Rice, K., Rottink, M., and Linhardt, R. (1987) Fractionation of heparin-derived oligosaccha-

rides by gradient PAGE. Biochem. J. 244, 515–522.

20. Ludwigs, U., Elgavish, A., Esko, J., and Roden, L. (1987) Reaction of unsaturated uronic

acid residues with mercuric salts. Biochem. J. 245, 795–804.

21. Drummond, K. J., Yates, E. A., and Turnbull. J. E. (2001) Electrophoretic sequencing of

heparin/heparin sulfate oligosaccharides using a highly sensitive fluorescent end label.

Proteomics (in press).

22. Lee, K. B., Al-Hakim, A., Loganathan, D., and Linhardt, R. J. (1991) A new method for

sequencing linear oligosaccharides on gels using charged fluorescent conjugates.

Carbohydr.Res. (1991) 214, 155–168

Anion-Exchange HPLC of HS and Heparin Saccharides 141

141

From

: Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 171: Proteoglycan Protocols

Edited by: R. V. Iozzo © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

14

Analytical and Preparative Strong Anion-Exchange

HPLC of Heparan Sulfate and Heparin Saccharides

Jeremy E. Turnbull

1. Introduction

Studies on the structure–function relationships of the complex linear polysaccha-

rides, known as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), are becoming increasingly important

as biological functions are established for them. However, structural analysis of GAGs

presents a difficult technical problem, particularly in the case of the N-sulfated GAGs

heparan sulfate (HS) and heparin, which display remarkable structural diversity (1). A

widely used and effective approach is to degrade the chains into smaller saccharide

units that can then be separated and analyzed. In this regard, strong anion-exchange

(SAX) HPLC techniques have proved particularly useful for both the analysis of disac-

charide composition (2,3) and the separation of complex mixtures of larger saccha-

rides (3–6). However, in many methods the columns used have been silica-based and

suffer from drawbacks related to poor stability of the support (e.g., inconsistency of

run times, peak broadening, and short column life). There is clearly a need for

improvements in column performance, especially for the purification of larger saccha-

rides to homogeneity for sequencing and bioactivity testing. This chapter describes

how a single type of polymer-based SAX column, ProPac PA1, can be used to provide

high-resolution separations of both disaccharides and larger oligosaccharides derived

from HS and heparin, with consistent elution times and excellent column performance

characteristics (see Notes 1 and 2). Disaccharides from chondroitin sulfate and

dermatan sulfate can also be separated (see Note 3). The improved resolution of sac-

charides compared to other SAX-HPLC methods, combined with the versatility and

longevity of the columns, makes them a valuable tool for purification and structural

analysis of HS/heparin and other GAG saccharides.

2. Materials

1. Gradient HPLC system (capable of mixing at least two solutions).

2. ProPac PA1 analytical columns (4 × 250 mm; Dionex).

142 Turnbull

3. Double-distilled water, pH 3.5: pH water to 3.5 using hydrochloric acid (high-purity HCl

such as Aristar grade from BDH-Merck).

4. Sodium chloride solution (1 M): dissolve 58.4 g of HPLC-grade sodium chloride (e.g.,

HiPerSolv grade from BDH Merck) in 1L distilled water, and pH to 3.5 using HCl. Filter

using a sintered glass filter or a 0.2 µm bottle-top filter.

5. Potassium dihydrogen phosphate solution (1 M, pH 4.6): dissolve 136.1 g of HPLC-grade

KH

2

PO

4

(e.g., HiPerSolv grade from BDH Merck) in 1L distilled water and filter using a

sintered glass filter or a 0.2-µm bottle-top filter.

6. Unsaturated disaccharide standards (for both HS/heparin and chondroitin/dermatan sulfate)

and heparitinases/chondroitinases are available from Seikagaku Kogyo (Tokyo).

3. Methods

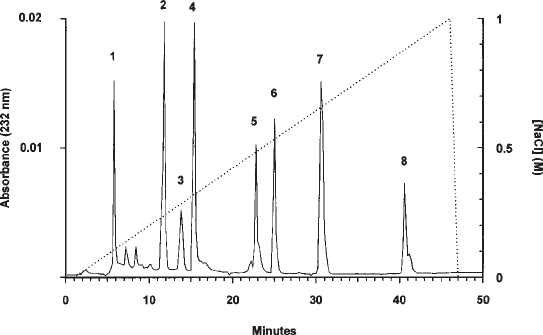

3.1. Separation of Unsaturated HS/Heparin Disaccharides

A simple and commonly used method to assess the structural composition of HS or

heparin is to depolymerize the chains to disaccharides with a mixture of bacterial

lyases. They can then be separated with reference to commercially available disaccha-

ride standards of known structure (see Fig. 1). Note that the eliminative cleavage

mechanism of the lyases results in unsaturated hexuronate residues in the resulting

disaccharides (see Note 4).

1. Prepare unsaturated disaccharides from heparin/HS by bacterial lyase treatment with

heparitinase I, heparitinase II, and heparinase; see ref. 7 for details.

2. After equilibration of the Pro-Pac PA1 column in mobile phase (double-distilled water

adjusted to pH 3.5 with HCl) at 1 mL/min, inject the sample.

3. After 1 min injection time, elute the disaccharides with a linear gradient of sodium chloride

(0–1 M over 45 min) in the same mobile phase.

4. Monitor the eluant in-line for UV absorbance at 232 nm (see Note 5).

5. Identify peaks by reference to standards separated under the same run conditions.

3.2. Separation of HS/heparin Disaccharides

Derived by Nitrous Acid Degradation

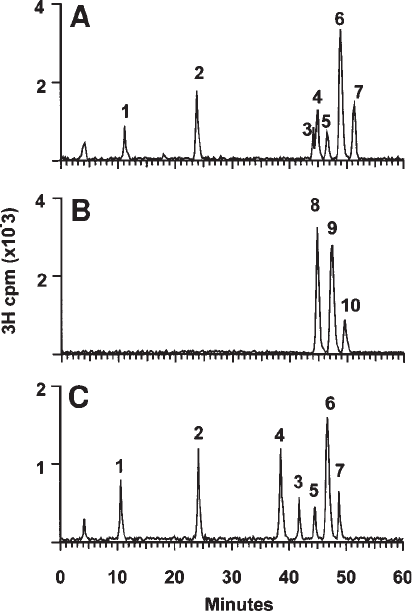

A further class of disaccharides, those derived by treatment of HS or heparin with

nitrous acid, are more difficult to resolve by SAX-HPLC. However, in contrast to the

lyase-derived saccharides, they have the advantage of containing intact hexuronate

residues (see Note 6). The most widely reported method for their separation uses a

silica-based SAX Partisil column with a KH

2

PO

4

gradient separation system (3). In

our hands this method gives very broad and inadequately resolved peaks, which limits

the sensitivity of detection and the accuracy of peak identification and quantitation. In

marked contrast, these disaccharides can be resolved well on a ProPac PA1 column

using appropriate shallow NaCl gradients. Resolution is improved slightly by use of

two columns connected in series (see Figs. 2A,B), but adequate results can also be

obtained using a single column. An alternative separation using a phosphate gradient

is described under Subheading 3.2.2.

3.2.1. Sodium Chloride Gradient

1. Prepare reduced

3

H-labeled disaccharides from heparin/HS by low-pH nitrous acid treat-

ment, either from unlabeled samples using

3

H-borohydride end-labeling (3) or from

samples radiolabeled biosynthetically using

3

H-glucosamine (8).

Anion-Exchange HPLC of HS and Heparin Saccharides 143

2. Separate samples on two ProPac PA1 columns in series, using the same mobile phase

described under Subheading 3.1., but with a two-step linear NaCl gradient (0–150 mM

over 50 min followed by 150–500 mM over 70 min).

3. Monitor

3

H radioactivity either with an in-line radioactivity detector or by collecting

fractions for scintillation counting (e.g., in Optiphase HiSafe III scintillant, Wallac).

See Note 7.

3.2.2. Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate Gradient

Improved separation of monosulfated disaccharides can be obtained using a gradi-

ent of phosphate (see Figure 2c and Note 8).

1. Using two ProPac PA1 columns in series, equilibrate in H

2

O, pH 6.0.

2. Inject samples and elute with a linear gradient of 0–1 M KH

2

PO

4

buffer, pH 4.6

over 90 min.

3. Monitor

3

H radioactivity as under Subheading 3.2.1.

3.3. Separation of HS/Heparin Oligosaccharides

In addition to separation of disaccharides, much larger HS and heparin oligosac-

charides can also be resolved on ProPac PA1 using a linear NaCl gradient (see Note 9).

Fig. 1. Separation of lyase-derived HS/heparin disaccharides on a ProPac PA1 column. The

profile shows the separation of the eight major unsaturated disaccharides released from these

polysaccharides by treatment with a combination of the bacterial lyases heparitinase I,

heparitinase II, and heparinase. The NaCl gradient is indicated by the dashed line. The struc-

tures of the standards and the amounts loaded were: 1, ∆-HexA-GlcNAc, 1 nmol; 2, ∆-HexA-

GlcNSO

3

, 2 nmol; 3, ∆-HexA-GlcNAc(6S), 0.5 nmol; 4, ∆-HexA(2S)-GlcNAc, 1.5 nmol;

5, ∆-HexA-GlcNSO

3

(6S), 1 nmol; 6, ∆-HexA(2S)-GlcNSO

3

, 1.5 nmol; 7, ∆-HexA(2S)-

GlcNAc(6S), 2 nmol; 8, ∆-HexA(2S)-GlcNSO

3

(6S), 1.5 nmol. Abbreviations: GlcNAc, N-acetyl

glucosamine; GlcNSO

3

, N-sulfated glucosamine; 2S, 3S, and 6S are 2-O-, 3-O-, and 6-O-sulfate

groups, respectively; ∆-HexA, unsaturated hexuronate residue formed at non-reducing end of

disaccharides and oligosaccharides by eliminative lyase scission.

144 Turnbull

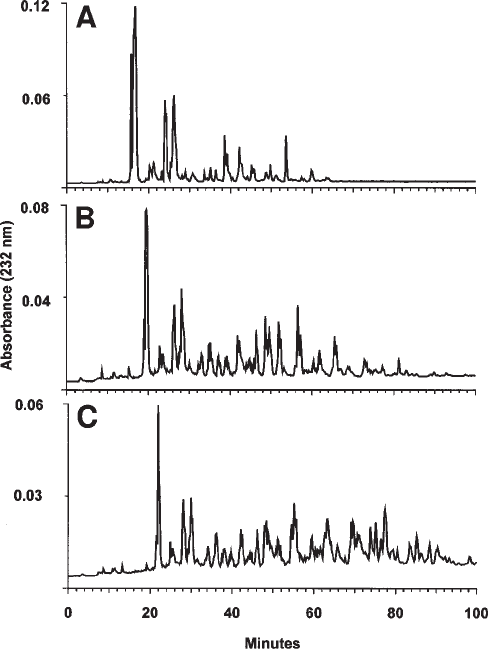

Figure 3 shows examples of separations performed on complex natural mixtures of

hexa-, octa-, and decasaccharides derived from porcine mucosal HS by treatment with

heparitinase I. It is noteworthy that the saccharides eluted in sets of resolved or

partially resolved peaks, which presumably have similar overall levels of anionic

charge but variant patterns of sulfation and disaccharide sequence. This method is

particularly useful for purification of saccharides to the degree necessary for sequencing

(12) or testing in biological assays (13). Preparative scale separations are also possible

(see Note 10).

Fig. 2. Separation of HNO

2

-derived HS/heparin disaccharides on a ProPac PA1 column.

These profiles show the separation of the major disaccharides released from HS/heparin by low-

pH nitrous acid treatment followed by

3

H-borohydride end labeling (3), or from

3

H-biosyn-

thetically labeled samples (8). The structures of the

3

H-labeled standards were: 1, IM/GM; 2,

M6S (monosaccharide); 3, G2SM; 4, I2SM; 5, GM3S; 6, GM6S; 7, IM6S; 8, I2SM6S; 9,

G2SM6S; and 10, GM3,6S (where G and I are glucuronic and iduronic acids, respectively; M

is 2,5-anhydromannitol; and 2S, 3S, and 6S are 2-O-, 3-O-, and 6-O-sulfate groups, respec-

tively). (A, B) show the first and last 60 min of the run time using a NaCl gradient as described

under Subheading 3.2.1. (C) shows the separation of non- and monosulfated disaccharides

using an alternative KH

2

PO

4

gradient as described under Subheading 3.2.2.

Anion-Exchange HPLC of HS and Heparin Saccharides 145

1. Prepare HS and heparin oligosaccharides (tetrasaccharides and larger) as described previ-

ously—for example, by partial depolymerization with heparitinase I and gel filtration on

Bio-Gel P6 (7–9).

2. Inject samples onto two ProPac PA1 columns in series, using the same mobile phase

described under Subheading 3.1.

3. Elute with a modified salt elution gradient (e.g., 0–1 M NaCl over 100 min).

4. Monitor the eluant in-line for UV absorbance at 232 nm.

4. Notes

1. During development of improved HPLC methods for separation of GAG saccharides

we found that a polymer-based column, ProPac PA1, originally designed primarily for

Fig. 3. Separation of HS oligosaccharides on a ProPac PA1 column. Porcine mucosal HS

was depolymerised with heparitinase I and hexa-, octa-, and deca-saccharide pools prepared by

gel filtration on Bio-Gel P6 (9) and resolved on two ProPac PA1 columns connected in series as

described under Methods. (A), hexasaccharides; (B), octasaccharides; (C), decasaccharides. In

each case, 100 nmol of each saccharide mixture was loaded (approximately 150, 200, and 250 µg

each, respectively).

146 Turnbull

SAX of proteins, provided excellent separations of disaccharides derived from the

glucosaminoglycans HS and heparin. Figure 1 shows the separation of the major unsatur-

ated disaccharides (detected by absorbance at 232 nm) derived by digestion of these polysac-

charides with a mixture of bacterial heparitinases. They elute as very sharp, symmetrical

peaks at highly reproducible elution times, and good baselining between all the peaks was

evident. These features of the separation provide more accurate identification of peaks and

sensitive quantitation than possible with previous methods. Note that

3

H or

35

S radiolabeled

disaccharides (derived from biosynthetically labeled polysaccharide) can also be separated

using this method, using in-line monitoring of radioactivity (see Fig. 2) or counting of

collected fractions.

2. Overall column performance is excellent. Elution times are highly consistent, and the col-

umns exhibit very good stability and longevity, which outweighs their initial high cost com-

pared to traditional silica columns. In one case a single column was used for more than 250

runs over a 2-yr period without significant loss of resolution. These properties are presum-

ably dependent on the column resin, which is formed by 0.2m anion exchange microbeads

being bonded to a 10-µm nonporous polystyrene/divinylbenzene polymeric resin.

3. Good separations of unsaturated disaccharides derived by chondroitinase ABC digestion of

the galactosaminoglycans chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate can also be obtained

using the ProPac-PA1 column. Similar results have been reported for the separation of this

class of disaccharides on another polymer-based column, the CarboPac PA1 (10).

4. The eliminative cleavage mechanism of the lyases results in unsaturated hexuronate resi-

dues (double bond between carbons 4 and 5 of the sugar ring) in the resulting disaccha-

rides (14). It is thus not possible to distinguish directly whether they resulted originally

from glucuronate or iduronate residues. In contrast, cleavage with nitrous acid leaves

these residues intact (see Note 6).

5. The limit of detection of unsaturated disaccharides by UV absorbance is approximately

20–50 pmol.

6. Nitrous acid cleaves between N-sulfated glucosamine residues and hexuronate residues.

The resulting saccharides have intact hexuronate residues but the reducing-end glucosamines

are converted to an anhydromannose residues (which are reduced to anhydromannitol by

reduction during preparation of the disaccharides).

7. When detecting radiolabeled samples, if accurate quantitation is required, be aware of the

potential for salt-dependent variability in counting efficiencies, depending on the

scintillant being used.

8. With in-line radioactivity monitoring, baselining between peaks is sufficient in most cases

to allow accurate quantitation of the individual major species. The exception is the partial

separation of I2SM from the rare disaccharide G2SM (see Fig. 2a). Note that slight

changes in run conditions (e.g., pH) can reverse their order of elution. However, condi-

tions using an

alternative KH

2

PO

4

buffer separation system give the best resolution of the

monosulfated disaccharide standards, including excellent baseline separations of I2SM

and G2SM when required (see Fig. 2c).

9. This approach is effective for separating saccharides up to approximately dp14-16 in size,

although the patterns become inherently more complex and resolution less efficient with

increasing size. Improved resolution can be obtained using shallower gradients than described

under Subheading 3.3. Additional examples of applications can be found in refs. 11–13.

10. Preparative separations are possible with loadings up to approximately 0.5–1.0 mg per

run on the 4 × 250 mm analytical columns, and a fivefold scale-up should be achievable

on 9 × 250 mm preparative columns that are available from Dionex.

Anion-Exchange HPLC of HS and Heparin Saccharides 147

References

1. Gallagher, J. T., Turnbull, J. E., and Lyon, M. (1992) Patterns of sulphation in heparan

sulphate: polymorphism based on a common structural theme. Int. J. Biochem. 24, 553–556.

2. Yoshida, K., Miyauchi, S., Kikuchi, H., Tawada, A., and Tokuyasu, K. (1989) Analysis of

unsaturated disaccharides from glycosaminoglycuronan by HPLC. Anal. Biochem. 177,

327–332.

3. Bienkowski, M. J. and Conrad, H. E. (1984) Structural characterisation of the oligosac-

charides formed by depolymerisation of heparin with nitrous acid. J. Biol. Chem. 260,

356–365.

4. Guo, Y. and Conrad, H. E. (1988) Analysis of oligosaccharides from heparin by reversed-

phase ion pairing HPLC. Anal. Biochem. 168, 54–62.

5. Linhardt, R. J., Gu, K., Loganathan, D., and Carter, S. R. (1989). Analysis of glycosami-

noglycan-derived oligosaccharides using reverse-phase ion-pairing and ion-exchange chro-

matography with suppressed conductivity detection. Anal. Biochem. 181, 288–296.

6. Rice, K. G., Kim, Y., Grant, A., Merchant, Z., and Linhardt, R. J. (1985) HPLC separation

of heparin-derived oligosaccharides. Anal. Biochem. 150, 325–331.

7. Turnbull, J. E. and Gallagher, J. T. (1991) Distribution of iduronate-2-sulphate residues in

heparan sulphate: evidence for an ordered polymeric structure. Biochem. J . 273, 553–559.

8. Turnbull, J. E., Fernig, D., Ke, Y., Wilkinson, M. C., and Gallagher, J. T. (1992) Identifica-

tion of the basic FGF binding sequence in fibroblast HS. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 10,337-10,341.

9. Walker, A., Turnbull, J. E., and Gallagher, J. T. (1994) Specific HS saccharides mediate

the activity of basic FGF. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 931–935.

10. Midura, R. J., Salustri, A., Calabro, A., Yanagashita, M., and Hascall, V. C. (1994) High-

resolution separation of disaccharide and oligosaccharide alditols from chondroitin sulphate,

dermatan sulphate and hyaluronan using CarboPac PA1 chromatography. Glycobiology 4,

333–342.

11. Sanderson, R. D., Turnbull, J. E., Gallagher, J. T., and Lander, A.D. (1994) Fine structure of

HS regulates cell syndecan-1 function and cell behaviour. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13,100–13,106.

12. Turnbull, J. E., Hopwood, J., and Gallagher, J. T. (1999) A strategy for rapid sequencing

of heparan sulphate/heparin saccharides. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2698–2703

13. Guimond, S. E. and Turnbull, J. E. (1999) Fibroblast growth factor receptor signalling is

dictated by specific heparan sulphate saccharides. Current Biology 9, 1343–1346.

14. Linhardt R. J., Turnbull J. E., Wang H., Loganathan D., and Gallagher J. T. (1990) Exami-

nation of the substrate specificity of heparin and heparan sulphate lyases. Biochemistry

29, 2611–2617.

Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting 149

149

From:

Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 171: Proteoglycan Protocols

Edited by: R. V. Iozzo © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

15

Proteoglycans Analyzed by Composite Gel

Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

George R. Dodge and Ralph Heimer

1. Introduction

Proteoglycans are the protein products of diverse genes posttranslationally modi-

fied with highly negatively charged side chains, commonly known as glycosami-

noglycans. The latter consist of repeating disaccharides capable of forming polymers

of varying size, which, depending on the specific disaccharide composition, are known

as the chondroitin sulfates, the iduronate-containing dermatan sulfates, keratan sul-

fate, and heparan sulfate. Some of the more complex proteoglycans, such as aggrecan,

are decorated by additional nonglycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides (1). Aggrecan

contains additionally a hyaluronan-binding domain that in the extracellular matrix

facilitates formation of large noncovalently-bound complexes containing one

hyaluronan molecule and numerous aggrecans (1). Analysis of proteoglycans by stan-

dard SDS-PAGE is complicated by the presence of the negatively charged side chains,

which prevent the linerarization of molecules usually achieved by treatment with a

mercaptoethanol and SDS. Consequently, in SDS-PAGE most proteoglycans with mul-

tiple glycosaminoglycan side chains, if they enter the gel at all, migrate as broad bands

and appear as smears due to size heterogeneity and large electroendosmotic effects

particularly when the acrylamide composition of the PAGE gel is held to a minimum.

The studies of McDevitt and Muir, now more than three decades ago, made the

surprising observation that the proteoglycans from an extract of cartilage resolved in

a composite gel composed of 0.6% agarose and 1.2% acrylamide into two sharp bands

(2). The mechanism for the separation of the proteoglycans of cartilage into two bands

appeared to be based not only on size but also on charge distribution of two subspe-

cies of proteoglycans (3). Gels such as these were originally designed to provide a

larger pore size than 3.5% acrylamide alone, which is the limit concentration for gel

formation. The technique of composite gel electrophoresis is best understood when

the historical perspective is considered and its usefulness in previous applications dis-

cussed. These types of composite gels had been used for the separation of proteins (4)