Hugo W.B., Russel A.D.(ed). Pharmaceutical Microbiology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

3.1.2

Environment

The microbial flora of the pharmacy environment is a reflection of the general hospital

environment and the activities undertaken there. Free-living opportunist pathogens,

such as Ps. aeruginosa can normally be found in all wet sites, such as drains, sinks and

taps. Cleaning equipment, such as mops, buckets, cloths and scrubbing machines, may

be responsible for distributing these organisms around the pharmacy; if stored wet

they provide a convenient niche for microbial growth, resulting in heavy contamination

of equipment. Contamination levels in the production environment may, however, be

minimized by observing good manufacturing practices, by installing heating traps in

sink U-bends, thus destroying one of the main reservoirs of contaminants, and by proper

maintenance and storage of equipment, including cleaning equipment. Additionally,

cleaning of production units by contractors should be carried out to a pharmaceutical

specification.

3.1.3 Packaging

Sacking, cardboard, card liners, corks and paper are unsuitable for packaging

pharmaceuticals, as they are heavily contaminated, for example with bacterial or

fungal spores. These have now been replaced by non-biodegradable plastic materials.

Packaging in hospitals is frequently re-used for economic reasons. Large numbers of

containers may be returned to the pharmacy, bringing with them microbial contaminants

introduced during use in the wards. Particular problems have been encountered in

the past with disinfectant solutions where residues of old stock have been 'topped

up' with fresh supplies, resulting in the issue of contaminated solutions to wards.

Re-usable containers must, therefore, be thoroughly washed and dried, and never

refilled directly.

Another common practice in hospitals is the repackaging of products purchased in

bulk into smaller containers. Increased handling of the product inevitably increases the

risk of contamination, as shown by one survey when hospital-repacked items were

found to be contaminated twice as often as those in the original pack (Public Health

Laboratory Service Report 1971).

3.2 In use

Pharmaceutical manufacturers may justly argue that their responsibility ends with

the supply of a well-preserved product of high microbiological standard in a

suitable pack and that the subsequent use, or indeed abuse, of the product is of

little concern to them. Although much less is known about how products become

contaminated during use, there is reasonable evidence that continued use of such products

is undesirable, particularly in hospitals where it may result in the spread of cross-

infection.

All multidose products are subject to contamination from a number of sources

during use. The sources of contamination are the same whether products are used in

hospital or in the community environment, but opportunities for observing it are, of

course, greater in the former.

Contamination of non-sterile pharmaceuticals 377

3.2.1 Human sources

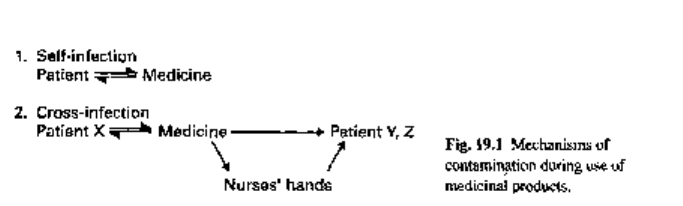

During normal usage, the patient may contaminate his/her medicine with his/her

own microbial flora; subsequent use of the product may or may not result in self-

infection (Fig. 19.1). Topical products are considered to be most at risk, since the

product will probably be applied by hand thus introducing contaminants from the

resident skin flora of staphylococci, Micrococcus spp. and diphtheroids but also perhaps

transient contaminants, such as Pseudomonas, which would normally be removed during

effective handwashing. Opportunities for contamination may be reduced by using

disposable applicators for topical products or by taking oral products by disposable

spoon.

In hospitals, multidose products, once contaminated, may serve as a vehicle of

cross-contamination or cross-infection between patients. Zinc-based products packed

in large stock-pots and used in the treatment and prevention of bed-sores in long-stay

and geriatric patients may become contaminated during use with organisms such as

Ps. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. These unpreserved products will allow

multiplication of contaminants, especially if water is present either as part of the

formulation, for example in oil/water (o/w) emulsions, as a film in w/o emulsions

which have undergone local cracking, or as a condensed film from atmospheric water,

and appreciable numbers may then be transferred to other patients when re-used. Clearly

the economics and convenience of using stock-pots need to be balanced against the

risk of spreading cross-infection between patients and the inevitable increase in length

of the patients' stay in hospital. The use of stock-pots in hospitals has noticeably declined

over the past decade or so.

A further potential source of contamination in hospitals is the nursing staff

responsible for medicament administration. During the course of their work, nurses'

hands become contaminated with opportunist pathogens which are not part of the normal

skin flora but are easily removed by thorough handwashing and drying. In busy wards,

handwashing between attending to patients may be omitted and any contaminants may

subsequently be transferred to medicaments during administration. Hand lotions and

creams used to prevent chapping of nurses' hands may similarly become contaminated,

especially when packaged in multidose containers and left at the side of the handbasin,

frequently without a lid. The importance of thorough handwashing cannot be over-

emphasized in the control of hospital cross-infection. Hand lotions and creams should

be well preserved and, ideally, packaged in disposable dispensers. Other effective control

methods include the supply of products in individual patient's packs and the use of a

non-touch technique for medicament administration.

378 Chapter 19

3.2.2

Environmental sources

Small numbers of airborne contaminants may settle out in products left open to the

atmosphere. Some of these will die during storage, with the rest probably remaining

at a static level of about 10

2

-10

3

colony forming units (cfu) g

_I

or ml

-1

. Larger

numbers of water-borne contaminants may be accidentally introduced into topical

products by wet hands or by a 'splash-back mechanism', if left at the side of a basin.

Such contaminants generally have simple nutritional requirements and, following

multiplication, levels of contamination may often exceed 10

6

cfug~' or ml

-1

. This

problem is encountered particularly when the product is stored in warm hospital wards

or in hot steamy bathroom cupboards at home. Products used in hospitals as soap

substitutes for bathing patients are particularly at risk, and soon not only become

contaminated with opportunist pathogens such as Pseudomonas spp., but also provide

conditions conducive for their multiplication. The problem is compounded by using

stocks in multidose pots for use by several patients in the same ward over an extended

period of time.

The indigenous microbial population is quite different in the home and in hospitals.

Pathogenic organisms are found much more frequently in the latter and consequently

are isolated more often from medicines used in hospital. Usually, there are fewer

opportunities for contamination in the home, as patients are generally issued with

individual supplies in small quantities.

3.2.3 Equipment sources

Patients and nursing staff may use a range of applicators (pads, sponges, brushes,

spatulas) during medicament administration, particularly for topical products. If re-

used, these easily become contaminated and may be responsible for perpetuating

contamination between fresh stocks of product, as has indeed been shown in

studies of cosmetic products. Disposable applicators or swabs should therefore always

be used.

In hospitals today a wide variety of complex equipment is used in the course

of patient treatment. Humidifiers, incubators, ventilators, resuscitators and other

apparatus require proper maintenance and decontamination after use. Chemical

disinfectants used for this purpose have in the past through misuse become contaminated

with opportunist pathogens, such as Ps. aeruginosa, and ironically have contributed

to, rather than reduced, the spread of cross-infection in hospital patients. Disinfectants

should only be used for their intended purpose and directions for use must be followed

at all times.

4 The extent of microbial contamination

Detailed examination of reports in the literature of medicament-borne contamination

reveals that the majority of these are anecdotal in nature, referring to a specific product

and isolated incident. Little information is available, however, as to the overall risk of

products becoming contaminated and causing patient infections when subsequently

used. As with risk analysis in food microbiology (assessment of the hazards of

Contamination of non-sterile pharmaceuticals 379

consumption of a contaminated preparation) this information is considered invaluable

not only because it indicates the effectiveness of existing practices and standards, but

also because the value of potential improvements in quality from a patient's point of

view can be balanced against the inevitable cost of such processes. Thus, the old

argument that all pharmaceutical products, regardless of their use, should be produced

as sterile products, although sound in principle, is kept in perspective by the fact that it

cannot be justified on economic grounds alone.

Contamination in manufacture

Investigations carried out by the Swedish National Board of Health in 1965 revealed

some startling findings on the overall microbiological quality immediately after

manufacture of non-sterile products made in Sweden. A wide range of products was

routinely found to be contaminated with Bacillus subtilis, Staph, albus, yeasts and

moulds, and in addition large numbers of coliforms were found in a variety of tablets.

Furthermore, two nationwide outbreaks of infection were subsequently traced to the

inadvertent use of contaminated products. Two hundred patients were involved in an

outbreak of salmonellosis, caused by thyroid tablets contaminated with Salmonella

bareilly and Sal. muenchen; and eight patients had severe eye infections following

the use of hydrocortisone eye ointment contaminated with Ps. aeruginosa. The results

of this investigation have not only been used as a yardstick for comparing the

microbiological quality of non-sterile products made in other countries, but also as a

baseline upon which international standards could be founded.

In the UK, the microbiological and chemical quality of pharmaceutical products

made by industry has since been governed by the Medicines Act 1968. The majority of

products have been found to be made to a high standard, although spot checks have

occasionally revealed medicines of unacceptable quality and so necessitated product

recall. By contrast, the manufacture of pharmaceutical products in hospitals has in the

past been much less rigorously controlled, as shown by the results of surveys in the

1970s in which significant numbers of preparations were found to be contaminated

with Ps. aeruginosa. In 1974, hospital manufacture also came under the terms of the

Medicines Act and, as a consequence, considerable improvements have been seen in

recent years not only in the conditions and standard of manufacture, but also in the

chemical and microbiological quality of finished products.

Furthermore, in the past decade hospital manufacturing operations have been

rationalized. Economic restraints have resulted in a critical evaluation of the true cost

of these activities; competitive purchasing from industry has in many cases produced

cheaper alternatives and small-scale manufacturing has been largely discouraged. Where

licensed products are available, NHS policy now dictates that these are purchased from

a commercial source and not made locally. Hospital manufacturing is at present

concentrated on the supply of bespoke products from a regional centre or small-scale

specialist manufacture of those items currently unobtainable from industry. Repacking

of commercial products into more convenient pack sizes is still, however, common

practice.

Removal of Crown immunity from the NHS in 1991 meant that manufacturing

operations in hospitals were then subject to the full licensing provisions of the Medicines

Act 1968, i.e. hospital pharmacies intending to manufacture were required to obtain a

manufacturing licence and to comply fully with the EC Guide to Good Pharmaceutical

Manufacturing Practice (1989, revised in 1992); amongst other requirements, this

included the use of appropriate environmental manufacturing conditions and associated

environmental monitoring. Subsequently, the Medicines Control Agency (MCA) issued

guidance in 1992 on certain manufacturing exemptions, by virtue of the product batch

size or frequency of manufacture. At the same time the need for extemporaneous

dispensing of 'one-off' special formulae continues in hospital pharmacies today, although

this work has largely been transferred from the dispensing bench to dedicated preparative

facilities with appropriate environmental control.

Contamination in use

Higher rates of contamination are invariably seen in products after opening and use,

and, amongst these, medicines used in hospitals are more likely to be contaminated

than those used in the general community. The Public Health Laboratory Service Report

of 1971 expressed concern at the overall incidence of contamination in non-sterile

products used on hospital wards (327 of 1220 samples) and the proportion of samples

found to be heavily contaminated (18% in excess of 10

4

cfug

-1

or ml

-1

). The presence

of Ps. aeruginosa in 2.7% of samples (mainly oral alkaline mixtures) was considered

to be highly undesirable.

By contrast, medicines used in the home are not only less often contaminated but

also contain lower levels of contaminants and fewer pathogenic organisms. Generally,

there are fewer opportunities for contamination here since smaller quantities are used

by individual patients. Medicines in the home may, however, be hoarded and used for

extended periods of time. Additionally, storage conditions may be unsuitable and expiry

dates ignored and thus problems other than those of microbial contamination may be

seen in the home.

Factors determining the outcome of a

medicament-borne infection

A patient's response to the microbial challenge of a contaminated medicine may be

diverse and unpredictable, perhaps with serious consequences. In one patient, no clinical

reactions may be evident, yet in another these may be indisputable, illustrating one

problem in the recognition of medicament-borne infections. Clinical reactions may

range from inconvenient local infections of wounds or broken skin, caused possibly

from contact with a contaminated cream, to gastrointestinal infections from the ingestion

of contaminated oral products, to serious widespread infections, such as a bacteraemia

or septicaemia, leading perhaps to death, as have resulted from infusion of contaminated

fluids. Undoubtedly, the most serious outbreaks of infection have been seen in the past

where contaminated products have been injected directly into the bloodstream of patients

whose immunity is already compromised by their underlying disease or therapy. The

outcome of any episode is determined by a combination of several factors, amongst

which the type and degree of microbial contamination, the route of administration and

the patient's resistance are of particular importance.

Contamination of non-sterile pharmaceuticals 381

5.1 Type and degree of microbial contamination

Microorganisms that contaminate medicines and cause disease in patients may be

classified as true pathogens or opportunist pathogens. Pathogenic organisms like

Clostridium tetani and Salmonella spp. rarely occur in products, but when present

cause serious problems. Wound infections from using contaminated dusting powders

have been reported, including several cases of neonatal death from talcum powder

containing CI. tetani. Outbreaks of salmonellosis have followed the inadvertent ingestion

of contaminated thyroid and pancreatic powders. On the other hand, opportunist

pathogens like Ps. aeruginosa, Klebsiella, Serratia and other free-living organisms

are more frequently isolated from medicinal products and, as their name suggests,

may be pathogenic if given the opportunity. The main concern with these organisms is

that their simple nutritional requirements enable them to survive in a wide range of

pharmaceuticals, and thus they tend to be present in high numbers, perhaps in excess

of 10

6

-10

7

cfug"' or ml

-1

; nevertheless, the product itself may show no visible sign of

contamination. Opportunist pathogens can survive in disinfectants and antiseptic

solutions which are normally used in the control of hospital cross-infection but which

when contaminated may even perpetuate the spread of infection. Compromised hospital

patients, i.e. the elderly, burned, traumatized or immunosuppressed, are considered to

be particularly at risk from infection with these organisms, whereas healthy patients in

the general community have given little cause for concern.

The critical dose of microorganisms which will initiate an infection is largely

unknown and varies not only between species but also within a species. Animal and

human volunteer studies have indicated that the infecting dose may be reduced

significantly in the presence of trauma or foreign bodies or if accompanied by a drug

having a local vasoconstrictive action.

5.2 The route of administration

As stated previously, contaminated products injected directly into the bloodstream or

instilled into the eye cause the most serious problems. Intrathecal and epidural injections

are potentially hazardous procedures. In practice, epidural injections are frequently

given through a bacterial filter. Injectable and ophthalmic solutions are often simple

solutions and provide Gram-negative opportunist pathogens with sufficient nutrients

to multiply during storage; if contaminated, numbers in excess of 10

6

cfu and endotoxins

should be expected. Total parenteral nutrition fluids, formulated for individual patients'

nutritional requirements, can also provide more than adequate nutritional support for

invading contaminants. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the notorious contaminant of eye-

drops, has caused serious ophthalmic infections, including the loss of sight in some

cases. The problem is compounded when the eye is damaged through the improper use

of contact lenses or scratched by fingernails or cosmetic applicators.

The fate of contaminants ingested orally in medicines may be determined by several

factors, as is seen with contaminated food. The acidity of the stomach may provide a

successful barrier, depending on whether the medicine is taken on an empty or full

stomach and also on the gastric emptying time. Contaminants in topical products may

cause little harm when deposited on intact skin. Not only does the skin itself provide an

382 Chapter 19

excellent mechanical barrier but, furthermore, few contaminants normally survive in

competition with its resident microbial flora. Skin damaged during surgery or trauma

or in patients with burns or pressure sores may, however, be rapidly colonized and

subsequently infected by opportunist pathogens. Patients treated with topical steroids

are also prone to local infections, particularly if contaminated steroid drugs are

inadvertently used.

Resistance of the patient

A patient's resistance is crucial in determining the outcome of a medicament-borne

infection. Hospital patients are more exposed and susceptible to infection than

those treated in the general community. Neonates, the elderly, diabetics and patients

traumatized by surgery or accident may have impaired defence mechanisms. People

suffering from leukaemia and those treated with immunosuppressants are most

vulnerable to infection; there is a strong case for providing all medicines in a sterile

form for these patients.

Prevention and control of contamination

Prevention is undoubtedly better than cure in minimizing the risk of medicament-borne

infections. In manufacture the principles of good manufacturing practice must be

observed, and control measures must be built in at all stages. Initial stability tests should

show that the proposed formulation can withstand an appropriate microbial challenge;

raw materials from an authorized supplier should comply with in-house microbial

specifications; environmental conditions, appropriate to the production process, require

regular microbiological monitoring; finally, end-product analysis should indicate that

the product is microbiologically suitable for its intended use and conforms to accepted

in-house and international standards.

Based on present knowledge, contaminants, by virtue of their type or number, should

not present a potential health hazard to patients when used.

Contamination during use is less easily controlled. Successful measures in the

hospital pharmacy have included the packaging of products as individual units, thereby

discouraging the use of multidose containers. Unit packaging (one dose per patient)

has clear advantages, but economic constraints prevent this desirable procedure from

being realized. Ultimately, the most fruitful approach is through the training and

education of patients and hospital staff, so that medicines are used only for their intended

purpose. The task of implementing this approach inevitably rests with the clinical and

community pharmacists of the future.

Further reading

Baird R.M. (1981) Drugs and cosmetics. In: Microbial Biodeterioration (ed. A.H. Rose), pp. 387-426.

London: Academic Press.

Baird R.M. (1985) Microbial contamination of pharmaceutical products made in a hospital pharmacy.

Pharm J, 234, 54-55.

Baird R.M. (1985) Microbial contamination of non-sterile pharmaceutical products made in hospitals

in the North East Regional Health Authority. J Clin Hosp Pharm, 10, 95-100.

Contamination of non-sterile pharmaceuticals 383

Baird R.M. & Shooter R.A. (1976) Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections associated with the use of

contaminated medicaments. Br Med J, 2, 349-350.

Baird R.M., Brown W.R.L. & Shooter R.A. (1976) Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospital pharmacies.

Br Med J, 1,511-512.

Baird R.M., Elhag K.M. & Shaw E.J. (1976) Pseudomonas thomasii in a hospital distilled water supply.

J Med Microbiol, 9, 493-495.

Baird R.M., Parks A. & Awad Z.A. (1977) Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in pharmacy

environments and medicaments. Pharm J, 119, 164-165.

Baird R.M., Crowden C.A., O'Farrell S.M. & Shooter R.A. (1979) Microbial contamination of

pharmaceutical products in the home. J Hyg, 83, 277-283.

Baird R.M. & Bloomfield S.F.L. (eds) (1996) Microbial Quality Assurance of Cosmetics, Toiletries

and Non-sterile Pharmaceuticals. London: Taylor and Francis.

Bassett D.C.J. (1971) Causes and prevention of sepsis due to Gram-negative bacteria: common sources

of outbreaks. Proc R Soc Med, 64, 980-986.

Crompton D.O. (1962) Ophthalmic prescribing. Australas J Pharm, 43, 1020-1028.

Denyer S.P. & Baird R.M. (eds) (1990) Guide to Microbiological Control in Pharmaceuticals. Chichester:

Ellis Horwood.

EC Guide to Good Manufacturing Practice (1992).

Hills S. (1946) The isolation of CI. tetani from infected talc. NZMedJ, 45, 419-423.

Kallings L.O., Ringertz O., Silverstolpe L. & Ernerfeldt F. (1966) Microbiological contamination of

medicinal preparations. 1965 Report to the Swedish National Board of Health. Acta Pharm Suecica,

3, 219-228.

Maurer I.M. (1985) Hospital Hygiene, 3rd edn. London: Edward Arnold.

Meers P.D., Calder M.W., Mazhar M.M. & Lawrie G.M. (1973) Intravenous infusion of contaminated

dextrose solution: the Devonport incident. Lancet, ii, 1189-1192.

Morse L.J., Williams H.I., Grenn F.P., Eldridge E.F. & Rotta J.R. (1967) Septicaemia due to Klebsiella

pneumoniae originating from a handcream dispenser. N Engl J Med, 277, 472-473.

Myers G.E. & Pasutto F.M. (1973) Microbial contamination of cosmetics and toiletries. Can J Pharm

Sci, 8, 19-23.

Noble W.C. & Savin J. A. (1966) Steroid cream contaminated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lancet,

i, 347-349.

Parker M.T. (1972) The clinical significance of the presence of microorganisms in pharmaceutical and

cosmetic preparations. J Soc Cosm Chem, 23, 415-426.

Report of the Public Health Laboratory Service Working Party (1971) Microbial contamination of

medicines administered to hospital patients. Pharm J, 207, 96-99.

Russell A.D., Hugo W.G. & Ayliffe G.A.J, (eds) (1998) Principles and Practice of Disinfection,

Preservation and Sterilization, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Smart R. & Spooner D.F. (1972) Microbiological spoilage in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. / Soc

Cosm Chem, 23, 721-737.

Principles and practice of sterilization

1 Introduction

2 Sensitivity of microorganisms

2.1 Survivor curves

2.2 Expressions of resistance

2.2.1 D-value

2.2.2 z-value

2.3 Sterility assurance

3 Sterilization methods

4 Heat sterilization

4.1 Sterilization process

4.2 Moist heat sterilization

4.2.1 Steam as a sterilizing agent

4.2.2 Sterilizer design and operation

4.3 Dry heat sterilization

4.3.1 Sterilizer design

4.3.2 Sterilizer operation

5 Gaseous sterilization

5.1 Ethylene oxide

Introduction

Sterilization is an essential stage in the processing of any product destined for parenteral

administration, or for contact with broken skin, mucosal surfaces or internal organs,

where the threat of infection exists. In addition, the sterilization of microbiological

materials, soiled dressings and other contaminated items is necessary to minimize the

health hazard associated with these articles.

Sterilization processes involve the application of a biocidal agent or physical

microbial removal process to a product or preparation with the object of killing or

removing all microorganisms. These processes may involve elevated temperature,

reactive gas, irradiation or filtration through a microorganism-proof filter. The success

of the process depends upon a suitable choice of treatment conditions, e.g. temperature

and duration of exposure. It must be remembered, however, that with all articles to be

sterilized there is a potential risk of product damage, which for a pharmaceutical

preparation may result in reduced therapeutic efficacy or patient acceptability. Thus,

there is a need to achieve a balance between the maximum acceptable risk of failing to

achieve sterility and the maximum level of product damage which is acceptable. This

is best determined from a knowledge of the properties of the sterilizing agent, the

properties of the product to be sterilized and the nature of the likely contaminants. A

suitable sterilization process may then be selected to ensure maximum microbial kill/

removal with minimum product deterioration.

Principles and practice of sterilization 385

5.1.1 Sterilizer design and operation

5.2 Formaldehyde

5.2.1 Sterilizer design and operation

6 Radiation sterilization

6.1 Sterilizer design and operation

6.1.1 Gamma-ray sterilizers

6.1.2 Electron accelerators

6.1.3 Ultraviolet irradiation

7 Filtration sterilization

7.1 Filtration sterilization of liquids

7.2 Filtration sterilization of gases

8 Conclusions

9 Acknowledgements

10 Appendix

11 Further reading

20

1 Sensitivity of microorganisms

The general pattern of resistance of microorganisms to biocidal sterilization processes

is independent of the type of agent employed (heat, radiation or gas), with vegetative

forms of bacteria and fungi, along with the larger viruses, showing a greater sensitivity

to sterilization processes than small viruses and bacterial or fungal spores. The choice

of suitable reference organisms for testing the efficiency of sterilization processes (see

Chapter 23) is therefore made from the most durable bacterial spores, usually represented

by Bacillus stearothermophilus for moist heat, certain strains of B. subtilis for dry heat

and gaseous sterilization, and B. pumilus for ionizing radiation.

Ideally, when considering the level of treatment necessary to achieve sterility a

knowledge of the type and total number of microorganisms present in a product, together

with their likely response to the proposed treatment, is necessary. Without this

information, however, it is usually assumed that organisms within the load are no more

resistant than the reference spores or than specific resistant product isolates. In the

latter case, it must be remembered that resistance may be altered or lost entirely by

laboratory subculture and the resistance characteristics of the maintained strain must

be regularly checked.

A sterilization process may thus be developed without a full microbiological

background to the product, instead being based on the ability to deal with a 'worst

case' condition. This is indeed the situation for official sterilization methods which

must be capable of general application, and modern pharmacopoeial recommendations

are derived from a careful analysis of experimental data on bacterial spore survival

following treatments with heat, ionizing radiation or gas.

However, the infectious agents responsible for spongiform encephalopathies such

as bovine spongiform encehalopathy (BSE) and Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD) exhibit

exceptional degrees of resistance to all known lethal agents. Recent work has even cast

doubts on the adequacy of the process of 18min exposure to steam at 134-138°C

which has been officially recommended for the destruction of these agents (and which

far exceeds the lethal treatment required to achieve adequate destruction of bacterial

spores).

2.1 Survivor curves

When exposed to a killing process, populations of microorganisms generally lose their

viability in an exponential fashion, independent of the initial number of organisms.

This can be represented graphically with a 'survivor curve' drawn from a plot of the

logarithm of the fraction of survivors against the exposure time or dose (Fig. 20.1). Of

the typical curves obtained, all have a linear portion which may be continuous (plot A),

or may be modified by an initial shoulder (B) or by a reduced rate of kill at low survivor

levels (C). Furthermore, a short activation phase, representing an initial increase in

viable count, may be seen during the heat treatment of certain bacterial spores. Survivor

curves have been employed principally in the examination of heat sterilization methods,

but can equally well be applied to any biocidal process.

386 Chapter 20