Holford Matthew, Stringer Keith. Border Liberties and Loyalties in North-East England, 1200-1400 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

xx

D/Wyb Wybergh

MS Machell 5 Transcripts, xvii cent.

(b) Kendal

WD/Crk Crackanthorpe of Newbiggin

WD/Ry Le Fleming of Rydal Hall

Durham Cathedral Library

MS Raine 52 Transcripts, xix cent.

MSS Randall 3, 5 Transcripts, xviii cent.

Durham County Record O ce, Durham

D/Gr Greenwell Deeds

D/Lo Londonderry Estates

D/Sa Salvin of Croxdale

D/Sh.H Sherburn Hospital

D/St Strathmore Estate

Durham University Library, Archives and Special Collections

(a) Palace Green

HNP/N Howard Family: Northumberland

SGD 54 Littleburn, Holywell and Na erton

(b) 5 e College

Durham Cathedral Muniments

Original Deeds, etc.

Elemos. Elemosinaria

Finc. Finchalia

Haswell Deeds

Loc. Locelli

Misc. Ch. Miscellaneous Charters

Pont. Ponti calia

Reg. Regalia

Sacr. Sacristaria

SHD Sherburn Hospital

Spec. Specialia

M2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxM2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xx 4/3/10 16:12:264/3/10 16:12:26

MANUSCRIPT AND RECORD SOURCES

xxi

Other Sources

Bursar’s Accounts

Cart. I–IV Cartularia, xv cent.

Cart. Vet. Cartuarium Vetus, xiii cent.

Reg. II Priory Register, xiv–xv cent.

Reg. Hat eld Register of Bishop omas Hat eld

(1345–81)

Rep. Mag. Repertorium Magnum, xv cent.

Essex Record O ce, Chelmsford

D/DBy/T27 Miscellaneous Deeds

Guildhall Library, London

MS 31302 Skinners’ Company

John Rylands Library, Deansgate, Manchester

Latin MS 236 Accounts of Queen’s Household, 1357–8

PHC Phillipps Charters

Lancashire Record O ce, Preston

DDTO Towneley of Towneley

Levens Hall, Cumbria

Medieval Deeds

Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln

Dean and Chapter Muniments

Dij/62/iii Lincolnshire Churches

Merton College, Oxford

Stillington Deeds

M2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxiM2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxi 4/3/10 16:12:264/3/10 16:12:26

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

xxii

Northamptonshire Record O ce, Northampton

Stopford- Sackville Muniments

Northumberland Collections Service, Woodhorn

324 Blackett- Ord of Whit eld

SANT/TRA Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne:

Transcripts of Records

Waterford Charters

ZBL Blackett of Matfen

ZMI Middleton of Belsay

ZSW Swinburne of Capheaton

North Yorkshire County Record O ce, Northallerton

ZAZ Hutton of Marske

ZBO Bolton Hall

ZIQ Meynell of Kilvington

ZQH Chaytor of Cro

Nottinghamshire Archives, Nottingham

DD/4P, 6P Portland of Welbeck, 4th and 6th Deposits

DD/FJ Foljambe of Osberton

Nottingham University, Manuscripts and Special Collections

PL/E11 Dukes of Portland: Northumberland Estates

St George’s Chapel Archives and Chapter Library,

Windsor Castle

XI.K. Ancient Deeds

Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Stratford- upon- Avon

DR 10 Gregory- Hood of Stivichall

M2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxiiM2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxii 4/3/10 16:12:264/3/10 16:12:26

MANUSCRIPT AND RECORD SOURCES

xxiii

Society of Antiquaries, London

MS 120 Wardrobe Book, 1316–17

MS 121 Wardrobe Book, 1317–18

York Minster Library and Archives

MS XVI.A.1 Cartulary of St Mary’s Abbey, York, xiv cent.

M2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxiiiM2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxiii 4/3/10 16:12:264/3/10 16:12:26

xxiv

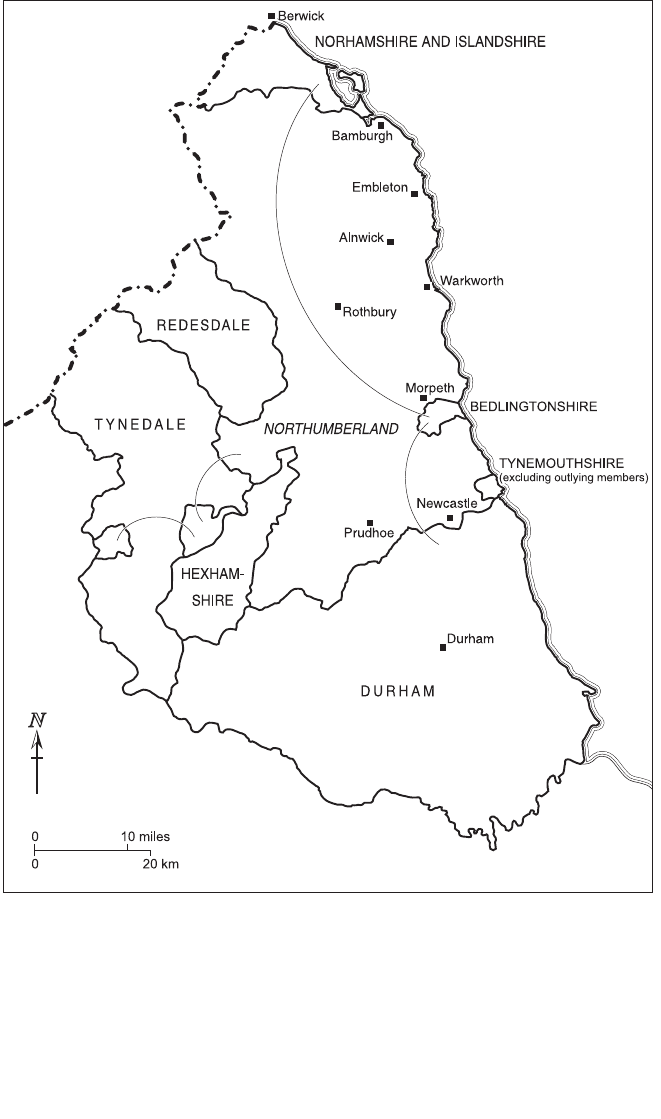

Map 1 The Greater Liberties of North-East England

M2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxivM2107 - HOLFORD PRELIMS.indd xxiv 4/3/10 16:12:264/3/10 16:12:26

1

Introduction

Matthew Holford and Keith Stringer

T

his book is the first full- length modern study of lordship and society

in the North- East of England in the thirteenth and fourteenth cen-

turies. In part it explores the workings of political life in the English

Borders in ways that may usefully advance research into the structures

and dynamics of medieval frontierlands. More particularly, by address-

ing the institutions and political cultures of medieval England beyond its

metropolitan heartlands, it aims to achieve fresh perspectives on the real-

ities of power and politics that underlay Westminster- centred orthodox-

ies about the English experience of ‘state- making’. And, above all, it seeks

to illuminate the significance of the greater north- eastern liberties – that

is, largely self- regulating territorial jurisdictions – for local authority and

governance and for socio- political cohesion and identification. Similarly,

while the North- East had its own setting and history, we hope that our

findings will have a wider bearing on the relevance of medieval England’s

liberties for people’s lives and loyalties, and will thereby contribute to

the mainstream of ongoing debates about ‘state’, ‘society’, ‘identity’ and

‘community’.

1

It is a commonplace that in our period England consolidated its position

as the most centralised ‘state’ in the medieval West. Indeed, even by about

1250 the authority of the English monarchy was ‘ubiquitous and, on its

own terms, exclusive’.

2

Yet a closer look at how power was distributed and

asserted in the mid- thirteenth- century kingdom is instructive. Much local

government was exercised not solely by the crown and its o cers, but in

di erent degrees through power- structures enjoying so- called ‘franchisal

1

For a broader conceptualisation, see K. J. Stringer, ‘States, liberties and communities

in medieval Britain and Ireland (c. 1100–1400)’, in M. Prestwich (ed.), Liberties and

Identities in the Medieval British Isles (Woodbridge, 2008), pp. 5–36.

2

R. R. Davies, The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles, 1093–1343

(Oxford, 2000), p. 93.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 1M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 1 4/3/10 16:12:504/3/10 16:12:50

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

2

rights’.

3

us liberties of various sorts (ignoring hundredal and lesser juris-

dictions) peppered the countryside from the English Channel to the Scottish

Border. e most typical were those with ‘return of writs’, which allowed

liberty- owners to execute all the normal duties and powers of the king’s

sheri s, and to hold courts equivalent to county courts, whose competence

was much inferior to that of full royal courts, but much superior to that of

ordinary honour or manor courts. Several earls and many bishops claimed

this prerogative, as did numerous religious houses such as the abbeys of

Abingdon, Chertsey, Cirencester, Evesham, Waltham and Westminster.

Return of writs was likewise a routine perquisite of privileged boroughs – in

1255–7, for example, no fewer than twenty- two towns received royal con-

rmations of this right – and it could also be held over large areas, including

the Isle of Wight, the Soke of Peterborough, Holderness, Richmondshire,

and most of Cambridgeshire and Su olk.

4

All fraunchise, as Chief Justice

Scrope was to state in 1329, ‘is to have jurisdiction and rule over the

people’;

5

and such liberties had a real e ect on the processes of local govern-

ance and control. ey therefore provide one important frame of reference

within which the operation of local power can be understood; and they

were in fact so widespread that none of the king’s counties was a uniform

legal and administrative unit under the sheri ’s direct supervision. Each

dissolves on examination into a jumble of jurisdictions.

6

During the course of Henry III’s reign (1216–72), a select number of

liberties were also formalising their rights to dispense royal justice in

their own courts. ey claimed cognisance of the civil pleas usually tried

before the king’s justices; their criminal jurisdiction covered the crown

pleas withdrawn from the king’s sheri s by Magna Carta of 1215. Most of

these liberties were located at ecclesiastical centres such as Battle, Beverley

and Ripon; and in some cases, as at Bury St Edmunds, Ely, Glastonbury

and Ramsey, no crown o cer took any part in the hearing of pleas. Even

these latter examples, however, did not represent the highest level of local

autonomy and authority: justice and administration were conducted

by liberty o cers, but o en on the basis of royal commands; and royal

writs were necessary to initiate the possessory assizes and other actions

3

Useful surveys include S. Painter, Studies in the History of the English Feudal Barony

(Baltimore, 1943), Chapter 4.

4

A key study is M. T. Clanchy, ‘The franchise of return of writs’, TRHS, 5th ser., 17 (1967),

pp. 59–82.

5

Quoted in A. Harding, Medieval Law and the Foundations of the State (Oxford, 2002), p.

214.

6

See, for example, B. English, ‘The government of thirteenth- century Yorkshire’, in J. C.

Appleby and P. Dalton (eds), Government, Religion and Society in Northern England,

1000–1700 (Stroud, 1997), pp. 90–103.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 2M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 2 4/3/10 16:12:504/3/10 16:12:50

INTRODUCTION

3

concerning freehold estates.

7

In contrast, the emergent ‘royal liberties’,

‘regalities’ or (ultimately) ‘counties palatine’ lay more completely outside

the orbit of crown jurisdiction, and were de ned primarily by the maxim

that ‘the king’s writ does not run there’. us in principle they were dis-

tinct self- governing entities, and in practice the king and his ministers

normally recognised their independent existence. ey possessed their

own separate ‘royal’ institutions, which were sta ed by their own person-

nel and replicated in microcosm the apparatus through which the ‘state’

could assert itself. Each liberty naturally had its own shire organisation;

crown and civil pleas were sued before the lord’s justices and by his

own writs; and it was already assumed that ‘regal jurisdiction’ included

exemption from parliamentary taxation. e lord himself was the main

focus of rule and law within the liberty, and it was his peace, not the king

of England’s peace, that was enforced locally. He also enjoyed broader

powers of lordship and patronage similar to those exercised by the crown

elsewhere in the kingdom; and his governmental and political authority

exceeded that of all other English liberty- owners save the ‘lords royal’ of

the March of Wales. Medieval England’s regalities included the earldom

of Chester and the palatinate of Lancaster (1351–61 and from 1377); the

other concentration was in the North- East.

e various kinds of liberty just described have long attracted scholarly

attention; yet, with the notable exception of Chester, the heyday of their

historiography was in the rst two- thirds of the twentieth century.

8

e

resulting studies, many of continuing value, are not easily summarised.

But beginning with Gaillard Lapsley’s pioneering book on Durham, pub-

lished as A Study in Constitutional History in 1900, they generally centred

on institutional theory and forms; and thanks mainly to Helen Cam’s

writings in the 1940s and 1950s, there was a marked predisposition to set

the history of liberties rmly within a power- map de ned by the English

crown according to its own speci cations. So it was that historians in

essence accepted the neat- and- tidy view of the world held by thirteenth-

century royal lawyers such as Henry Bracton, who took it for granted that

all jurisdiction derived from the crown and was exercised exclusively in its

name. Indeed, Cam wrote of ‘the king’s government as administered by the

7

M. D. Lobel, ‘The ecclesiastical banleuca in England’, in Oxford Essays in Medieval History

(Oxford, 1934), pp. 122–40; and, most recently, A. Gransden, A History of the Abbey of

Bury St. Edmunds, 1182–1256 (Woodbridge, 2007), Chapter 20.

8

Recent work on medieval Cheshire, especially its administrative history, amounts to a

small industry. See, for example, P. H. W. Booth, The Financial Administration of the

Lordship and County of Chester, 1272–1377 (Chetham Society, 1981); D. J. Clayton, The

Administration of the County Palatine of Chester, 1442–1485 (Chetham Society, 1990); P.

Morgan, War and Society in Medieval Cheshire, 1277–1403 (Chetham Society, 1987).

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 3M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 3 4/3/10 16:12:504/3/10 16:12:50

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

4

greater abbots of East Anglia’: liberty- owners were thus to be regarded as

royal surrogates and servants, while their o cials were also characterised

as ‘the king’s ministers and baili s’.

9

Likewise something of a Bractonian

consensus emerged that medieval ‘state- formation’ depended not on any

dynamic of governmental pluralism but on the integrating force of central

authority and institutions. Accordingly a paradigm was constructed of the

linear expansion of crown power and centralisation, so that even ‘royal

liberties’ were relegated to the historical sidelines on the grounds that they

became much like standard counties. ‘ eir in ated reputations’, Jean

Scammell observed, ‘falsify many assessments of the e ectiveness of mon-

archy and the possible extent of immunities in medieval England’; and she

went on to conclude that Durham should be seen as little more than ‘an

enormous estate situated in a remote part of England’.

10

In similar vein,

James Alexander categorised Chester, Durham and Lancaster as ‘puny local

quasi- autonomies’, and believed that, so far as Edward I and Edward III

were concerned, ‘the reality of power they shared not’.

11

is was a far cry from the view of Robin Storey (echoing Lapsley) that

the bishops of Durham ‘exercised an authority equal in its scope to that of

the King elsewhere in the realm’.

12

Rather, liberties of all types were merely

‘cogs’ in the ‘magni cent machine’ of medieval English royal governance.

13

Or, as Eleanor Searle argued in her work on Battle, a liberty’s place in the

local governmental and political order was decided by the king’s decree.

14

ere was thus much less interest in the actual powers of liberty- owners

over those whom they might call their ‘subjects’; or in how a liberty’s insti-

tutional and political frameworks might have bene ted local society and

shaped its behaviour, values and loyalties. And traditional approaches have

indeed cast a long shadow. Robert Palmer, for instance, set his analysis

of the relationship between the jurisdictions of county courts and liberty

courts largely within the context of their integration into a single ‘national’

9

H. M. Cam, Liberties and Communities in Medieval England, new edn (London, 1963),

pp. 183–204, and her ‘Shire officials: coroners, constables, and bailiffs’, in J. F. Willard et

al. (eds), The English Government at Work, 1327–1336 (Cambridge, MA, 1940–50), iii, p.

149.

10

J. Scammell, ‘The origin and limitations of the liberty of Durham’, EHR, 81 (1966), pp.

452, 473. Cf. R. B. Dobson, Church and Society in the Medieval North of England (London,

1996), p. 89: ‘the capacity of the bishops . . . of Durham to play an autonomous role on the

Anglo- Scottish Border was virtually non- existent’.

11

J. W. Alexander, ‘The English palatinates and Edward I’, JBS, 22 (1983), p. 22.

12

Storey, Langley, p. 52; cf. Lapsley, Durham, p. 76.

13

Cam, Liberties and Communities, pp. 207, 216.

14

E. Searle, Lordship and Community: Battle Abbey and its Banlieu, 1066–1538 (Toronto,

1974), p. 222: ‘for the franchise to be . . . maintained, it had constantly to be reinterpreted,

and reinterpretation depended upon the king’.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 4M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 4 4/3/10 16:12:504/3/10 16:12:50

INTRODUCTION

5

justice system.

15

More recent work by legal historians has tended, directly

or indirectly, to endorse such formulations and conclusions.

16

ey like-

wise sit easily with some current interpretations of the late- medieval

English constitution. us, to cite Helen Castor, ‘the hierarchies of govern-

ment, both formal and informal, depended fundamentally on the universal

and universally representative authority of the crown’.

17

Admittedly conceptions of this sort have not gone unchallenged. Rees

Davies urged us to recognise that medieval government was everywhere

less uniform and unipartite than étatist story- lines presuppose. ‘We

should’, so we learn, ‘beware of reifying the state, of accepting its own

de nition of, and apologia for, itself.’

18

For later medieval England, Gerald

Harriss has made clear the complexities of the interplay between the

‘public’ and the ‘private’ aspects of local power, and how the ‘private’ could

mesh with, parallel or rival the ‘public’.

19

More particularly, some historians

of England’s liberties have explicitly called into question the homogenising

capacity of the crown’s superiority and control. Edward Miller cautioned

against the notion that the thirteenth century saw ‘a taming of liberties,

a harnessing of their machinery to the machinery of the state’.

20

We have

also been reminded that individual liberty- owners might jealously defend

their prerogatives against royal encroachment by insisting that they were

independent local rulers, who enjoyed a lawful jurisdiction ‘from time

out of mind’.

21

Nor did Simon Walker doubt that John of Gaunt, as duke

of Lancaster, was ‘the only source of justice and patronage within his

palatinate’, or that his lordship was ‘almost unrestrained by the exercise

of royal power’.

22

Even lesser liberties, in Rodney Hilton’s opinion, were

signi cant nodes of local governance since what mattered in ‘an inevitably

decentralized state’ was the law as administered by the immediate lord.

23

15

R. C. Palmer, The County Courts of Medieval England, 1150–1350 (Princeton, 1982),

Chapter 9.

16

Compare, for example, the important review of A. Musson and W. M. Ormrod, The

Evolution of English Justice (London, 1999), by C. Donahue, Jr, in Michigan Law Review,

98 (2000), pp. 1725–37.

17

H. Castor, The King, the Crown, and the Duchy of Lancaster (Oxford, 2000), p. 306.

18

R. R. Davies, ‘The medieval state: the tyranny of a concept?’, Journal of Historical Sociology,

16 (2003), p. 289.

19

G. Harriss, Shaping the Nation: England, 1360–1461 (Oxford, 2005), especially pp.

163–75.

20

E. Miller, The Abbey and Bishopric of Ely (Cambridge, 1951), p. 242.

21

For example, A. Gransden, ‘John de Northwold, abbot of Bury St. Edmunds (1279–1301),

and his defence of its liberties’, TCE, 3 (1991), pp. 91–112.

22

S. Walker, The Lancastrian Affinity, 1361–1399 (Oxford, 1990), p. 179, and his ‘Lordship

and lawlessness in the palatinate of Lancaster, 1370–1400’, JBS, 28 (1989), p. 328.

23

R. H. Hilton, A Medieval Society: The West Midlands at the End of the Thirteenth Century

(London, 1966), p. 219.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 5M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 5 4/3/10 16:12:504/3/10 16:12:50