Holford Matthew, Stringer Keith. Border Liberties and Loyalties in North-East England, 1200-1400 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

226

had to be obtained at Westminster or from royal itinerant justices, it must

still have been cheaper and easier to pursue a plea locally. Attempting to

have a case moved to the liberty court also o ered a way of thwarting or

delaying an opponent’s case before the king’s justices. But for the same

reasons it might be prudent to have a case moved from the liberty’s court

to the crown’s; and against the convenience of the liberty must be set the

power and authority of the royal courts.

ese di culties, furthermore, were aggravated by the con scation of

the liberty in 1291. During the con scation the liberty’s court apparently

ceased to function: in the 1293 eyre, while crown pleas for Tynemouthshire

were heard separately, civil pleas are scattered among the county rolls.

287

Inhabitants of the liberty were forced to plead in the royal courts, and once

the habit had been established, it may have been di cult to break. Although

the priory had re- established some control over pleas by 1330, the royal

courts retained their attraction; and once a plea had reached these courts, it

was not always easy to have it transferred.

288

Indeed, it seems that the priory

did not even attempt to have all pleas transferred, so that it retained less

control over its tenants than did several relatively minor liberties.

289

And

there is no evidence, perhaps surprisingly, that any measures were taken

against tenants who sued outside the liberty.

e liberty’s court remained a powerful vehicle of the priory’s lord-

ship, not only in successfully removing a large number of cases from the

royal courts, but in its own right: it was in the ‘free court’ of the liberty, for

example, that a tenant in Backworth was judged to owe the prior £6.6s.8d.

in 1330.

290

e bulk of the evidence, however, suggests that the rst and

principal resort of many of the liberty’s inhabitants was the royal courts.

e liberty’s court was imposed on its inhabitants, rather than chosen by

them – it served lordship, not community.

Geography, a restricted level of privilege, dissatisfaction with the priory’s

lordship – all this meant that Tynemouthshire did not come to embrace all

aspects of its inhabitants’ lives. But if it was not, therefore, ‘the fundamental

fact of their governance’,

291

it was nevertheless one of these fundamental

287

Tynemouth Cart., ff. 192–4v, 203r–4v; NCH, viii, pp. 218–20; NER, nos. 127, 168, 208,

etc.

288

For one example of the potential complexities, see Year Books of the Reign of King Edward

the Third: Year XVIII, ed. L. O. Pike (RS, 1904), pp. 142–53.

289

Cases the priory seems not to have claimed include CP 40/282, m. 220. For other liberties,

see for example Index of Placita de Banco, 1327–28 (Lists and Indexes, 1909), passim.

290

NCH, ix, p. 35, n. 4.

291

E. Searle, Lordship and Community: Battle Abbey and its Banlieu, 1066–1538 (Toronto,

1974), p. 197.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 226M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 226 4/3/10 16:12:574/3/10 16:12:57

HEXHAMSHIRE AND TYNEMOUTHSHIRE

227

facts, and its ill- de ned privileges continued to allow a certain amount of

jurisdictional expansion. If the priory’s control over civil pleas was increas-

ingly precarious, it retained considerable power over criminal justice, whose

importance in local society should not be underestimated.

292

By 1321, at

the latest, the priory was again holding its own sessions of gaol delivery.

293

And to glance ahead to the nal years of the liberty, in the early sixteenth

century, is to nd the prior’s claiming on the basis of Richard I’s charter

the right to appoint his own justices of the peace. is was, furthermore, at

a time when Tynemouth and Newcastle were in dispute ‘for liberties and

franchises’, and when the priory used judicial commissions to prosecute

Newcastle’s supporters.

294

In the 1510s, as much as in the 1270s or 1280s,

the liberty had a real importance in local society – but largely because it was

an e ective instrument of the priory’s interests.

e description of liberties as merely ‘the judicial or quasi- judicial exter-

nal shell of lordship’ does not do justice to the great regalities of Durham,

Tynedale or even Hexhamshire.

295

In the case of Tynemouthshire, however,

it is much more appropriate. e liberty’s administration did o er some

opportunities for its middling tenants, and the priory’s spiritual signi -

cance also ensured it some local support. But its privileges were not su -

cient to provide signi cant nancial or judicial bene ts to the inhabitants of

the liberty. ey were adequate only to serve the interests of the priory, and

for this reason it was ‘freedom from the franchise’ that some of the liberty’s

greater tenants sought.

292

Cf. Dyer, Lords and Peasants, pp. 77–8; R. H. Hilton, A Medieval Society: The West

Midlands at the End of the Thirteenth Century (London, 1966), Chapter 8.

293

NCH, v, p. 299, n. 1.

294

KB 27/1078, rex, m. 7–7d; C 1/389/32; KB 9/467, m. 44; 9/964, m. 133; H. Garrett-

Goodyear, ‘The Tudor revival of Quo Warranto and local contributions to state building’,

in M. S. Arnold et al. (eds), On the Laws and Customs of England (Chapel Hill, NC, 1981),

pp. 264–5.

295

Davies, Lordship and Society, p. 222 (note that the quotation does not reflect an opinion

to which Davies himself subscribed).

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 227M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 227 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 228M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 228 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

PART II

THE SECULAR LIBERTIES

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 229M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 229 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 230M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 230 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

231

6

Tynedale: Power, Society and Identities,

c. 1200–1296

Keith Stringer

T

ynedale has good claims to be regarded as one of the greatest liberties in

the medieval British Isles, and it was certainly the largest and most priv-

ileged secular ‘franchise’ in the far North of England. Its position as a liberty

on the regional power- map was indeed second only to that of Durham; but

its history is much less well known. Margaret Moore highlighted Tynedale’s

significance as one of the English territories held by the Scottish crown after

the surrender of the northern counties to Henry II in 1157; Madeleine Hope

Dodds covered north Tynedale for the Northumberland County History;

and both writers drew on the pioneering work of the noted Northumbrian

antiquarian, John Hodgson (d. 1845).

1

Yet study of medieval Tynedale as

a liberty and a society did not advance far beyond the point where Dodds

left it in 1940. The limitations of the surviving records provide one reason

for this lack of interest. By contrast with Durham’s rich documenta-

tion, the Tynedale archive is fragmented, uneven and slight – though the

liberty’s eyre rolls of 1279–81 and 1293, and the Tynedale deeds among

the Swinburne of Capheaton muniments, do give some vital purchase.

2

Another explanation for Tynedale’s relative neglect is that, as a Scottish-

controlled liberty in England (1158–1286), it has fallen outside the normal

modus operandi of English and Scottish historians alike.

is chapter attempts to put the liberty more rmly on the historical

map of ‘Middle Britain’ in the thirteenth century, for most of which period

Tynedale was held by William I (‘the Lion’) and his successors Alexander

II (1214–49) and Alexander III (1249–86). It is indeed with the liberty’s

1

M. F. Moore, The Lands of the Scottish Kings in England (London, 1915), passim; NCH, xv,

pp. 155ff. Hodgson addressed south Tynedale in the third of his topographical volumes,

HN, II, iii, and also published relevant documents, notably in the first of his record

volumes, HN, III, i.

2

The 1279–81 roll, JUST 1/649, is printed in Hartshorne, pp. ix–lxviii, and extracts are

translated in CDS, ii, no. 168. The 1293 roll, JUST 1/657, is unpublished. Most of the

medieval Tynedale material in NCS, Swinburne (Capheaton) Estate Records, ZSW, was

printed by Hodgson, but with varying degrees of completeness and accuracy.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 231M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 231 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

232

fortunes under these Scots kings that we are primarily concerned, though

the concluding section will take matters down to the outbreak of the Wars

of Independence in 1296. Before that happened, Tynedale was long a land

of peace. Alexander II went to war in alliance with the ‘Northerners’ in

1215 to prosecute his historic rights to Northumberland, Cumberland and

Westmorland; but the years 1217–96 formed an era of unprecedented equi-

librium in Anglo- Scottish relations, despite occasional and (from 1292)

mounting tensions. Accord was cemented by Alexander II’s marriage to

Henry III’s sister Joan (1221) and by Alexander III’s marriage to Henry’s

eldest daughter Margaret (1251). It was underpinned by the Treaty of York

(1237), whereby Alexander II accepted for good that the Tweed–Solway

line was a xed international frontier in return for a Cumberland lordship

based on Penrith, some twelve miles from Tynedale’s bounds. Yet no analy-

sis of political society in the thirteenth- century English Borders should

underestimate how far the Scottish monarchy upheld its traditional role as

an arbiter of power and loyalty within the region, least of all its continued

ability to structure a world whose concepts of dominion and allegiance

were o en at odds with the assumptions and theoretical claims of English

royal governance.

3

It was within this broader context that the liberty and its

‘community’ developed; and much of this chapter focuses on how, and how

e ectively, the king of Scots asserted his authority as lord of Tynedale and,

above all, on the signi cance this liberty then had for people’s practices,

values and identities.

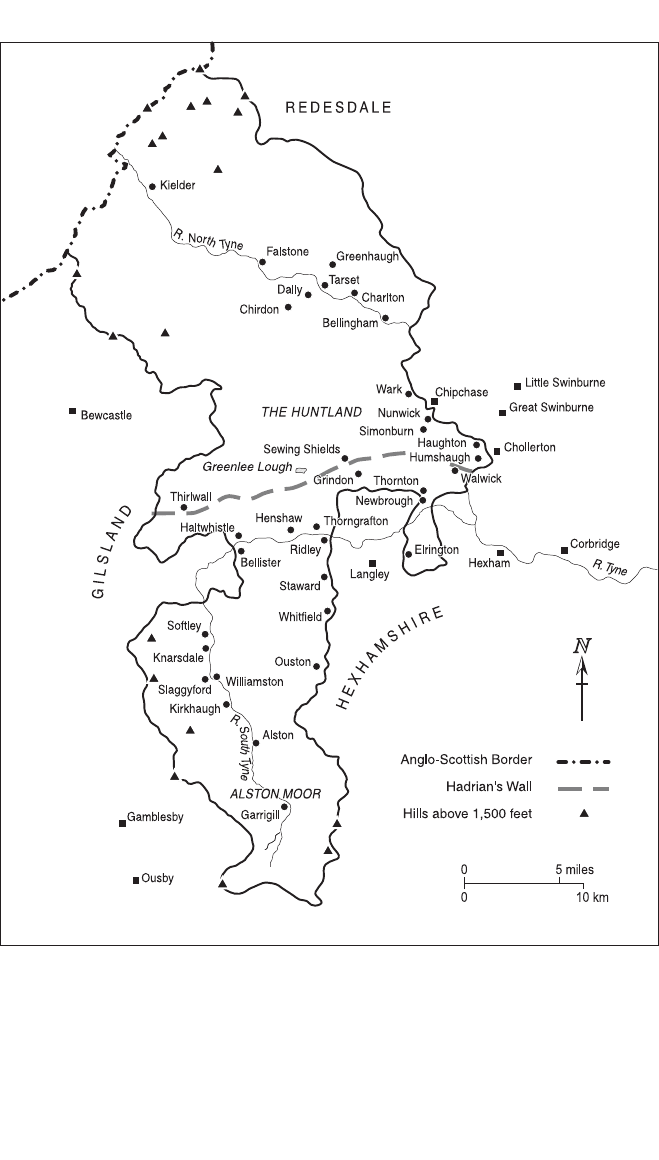

At its greatest extent, the liberty comprised about 480 square miles –

approximately half the size of Durham ‘between Tyne and Tees’, and one-

quarter of the area of the modern county of Northumberland. Its northern

boundary marked out the Border between Scotch Knowe and Carter Fell;

its interior had a maximum breadth of nineteen miles, between Black Hill

and Shawbush (in Bellingham), and a maximum length of forty- three

miles, between Carter Fell and Cross Fell. Much of the boundary circuit

preserved the outlines of ancient power- structures embracing the North

and South Tyne valleys. e old territorial pattern had, however, lost

some of its cohesion when in 1157 or 1158 Henry II created the barony of

3

See my ‘Identities in thirteenth- century England: frontier society in the far North’, in C.

Bjørn, A. Grant and K. J. Stringer (eds), Social and Political Identities in Western History

(Copenhagen, 1994), pp. 28–66; ‘Nobility and identity in medieval Britain and Ireland:

the de Vescy family, c. 1120–1314’, in B. Smith (ed.), Britain and Ireland, 900–1300

(Cambridge, 1999), pp. 199–239; ‘Kingship, conflict and state- making in the reign of

Alexander II: the war of 1215–17 and its context’, in R. D. Oram (ed.), The Reign of

Alexander II, 1214–49 (Leiden, 2005), pp. 99–156.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 232M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 232 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

TYNEDALE: POWER, SOCIETY AND IDENTITIES

233

Map 5 The Liberty of Tynedale

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 233M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 233 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

234

Langley, which drove two salients into Tynedale’s middle reaches where

otherwise it would have controlled the strategic Tyne Gap corridor all

the way from the outskirts of Hexham to Denton Fell.

4

Travel within the

liberty was not easy. e terrain o en rises to well above 600 feet, and in

Tynedale’s northern and southern extremities peaks of over 1,500 feet are

the norm. e other obvious obstacle to communication, especially on the

north–south axis, was the South Tyne. ere were no good bridges across

it inside the liberty, and in wet weather the fords could be used only ‘with

great fear and risk’.

5

As was appropriate for a countryside where cattle

and sheep as a rule presided, settlement patterns were dispersed, notably

in the zone later called ‘the Highlands’ beyond Wark, Bellingham and

Greenhaugh.

6

is was part of the vast parish of Simonburn; conversely

the area south of Hadrian’s Wall contained ve parish churches – Alston,

Haltwhistle, Kirkhaugh, Knarsdale and Whit eld – and it was there that the

liberty’s socio- economic centre of gravity in essence lay. us Tynedale was

not a landscape that readily lent itself to regular interaction throughout its

length, governmentally or otherwise. In the 1604 survey of the liberty, it was

said to be divided into North Tynedale and South Tynedale, partly on the

line of the Wall.

7

Earlier sources allude to a division of the same sort; and in

the fourteenth century such a division had a pronounced geopolitical and

social reality. Nevertheless thirteenth- century records assume the existence

of a single territorial unit, with its own distinct identity and unitary struc-

tures of local governance and social organisation. Nor in fact were such

assumptions seriously wide of the mark.

8

Despite the inroads made in the 1150s, Tynedale had the intrinsic

advantage of being an integral block of landed power, whose compact-

4

On Langley’s topography, see CIPM, xii, pp. 17–18, 208–9, 360–2; L. C. Coombes, ‘The

survey of Langley barony, 1608’, AA, 4th ser., 43 (1965), pp. 261–73; and, for its control

of the Newcastle–Carlisle road, The Register and Records of Holm Cultram, ed. F. Grainger

and W. G. Collingwood (CWAAS, Record Series, 1929), no. 100a. Tynedale was in Henry

II’s hands from summer 1157 to about Michaelmas 1158.

5

Chronique de Jean le Bel, ed. J. Viard and E. Déprez (Paris, 1904–5), i, p. 62. There was

a bridge near Ridley; but the main one was outside Tynedale at Haydon: Hartshorne, p.

xlviii; Lucy Cart., no. 175. Drownings, mostly in ‘the Tyne’, account for about two- fifths

of some sixty- five accidental deaths recorded in the eyre rolls.

6

NCH, xv, p. 266; NCS, ZSW/11/2.

7

Survey of the Debateable and Border Lands, etc., ed. R. P. Sanderson (Alnwick, 1891), p.

49.

8

The use simply of ‘Tynedale’ as the territorial name of the whole liberty is recorded from

the 1150s. But it could be called ‘North Tynedale’ or ‘West Tynedale’ to distinguish it from

Langley – sometimes known as ‘the barony of Tynedale’ – and from Tynedale ward, an

administrative subdivision of the county of Northumberland. In this and the next chapter,

‘north Tynedale’ and ‘south Tynedale’ are normally used as terms of convenience and,

broadly speaking, adopt the Wall as the dividing- line.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 234M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 234 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58

TYNEDALE: POWER, SOCIETY AND IDENTITIES

235

ness contrasted sharply with the scrambled con guration of ordinary

Northumbrian baronies. It also dwarfed Liddesdale to the north, Redesdale

and Hexhamshire to the east, and Bewcastledale and Gilsland to the west.

Indeed, no other ‘provincial lordship’ in the Marches proper, not even

Annandale, occupied more of the countryside.

9

By these yardsticks, the

lord of Tynedale was in an exceptionally strong position to master space

and people. Moreover, he was not just any Border magnate but the ruler

of another kingdom, whose monarchical aura, power and patronage repre-

sented a further vital reinforcement of the conventional content of lordly

domination and control. It was a circumstance unique in the history of the

greater English liberties, and one that arguably moulded thirteenth- century

Tynedale’s character more than did any other. Nor must we underestimate

the in uence of the past. For though, during Henry I’s reign (1100–35),

the silver mines of Alston had been annexed to the bailiwick of Carlisle, it

was probably not until 1157 that all Tynedale rst came under the sover-

eign authority of the English crown; and the historic political and cultural

context therefore points to an age- old preference for Scottish rule.

10

ese

indeed were weighty factors with a real potential in themselves to forge

close relations between lordship, territory and ‘community’.

As a power- system the liberty was thus more than merely the sum of its

‘franchises’, and this is a theme to which we will o en return. But its admin-

istrative and judicial privileges assuredly made the lord/king’s local author-

ity more exacting, e ective and monopolistic and, by the same token, more

likely to shape the lives and loyalties of those within its ambit. To say that

‘the kings of Scotland had practically the same rights in the liberty as they

had in their kingdom’ rather understates the case.

11

By Scottish standards,

the prerogatives at their command were greater than those they were o en

able to claim and enforce in the outer reaches of the realm. Tynedale was, in

English terms, a ‘royal liberty’; it thus enjoyed privileges virtually as exclu-

sive as those of Durham, and a similar standing as a jurisdiction outside

the normal sphere of crown control. ough explicit ‘palatine’ claims

would not be articulated for Tynedale until the 1330s,

12

the 1279–81 eyre

roll – it is the ‘rex’ roll made for Alexander III – represented the liberty as

a mature self- governing entity. e nodal focus of local administration and

justice was its head court, called the shire court (comitatus); its ordinary

9

Tynedale was important enough to feature on Matthew Paris’s maps of Britain (c. 1250),

where the only other districts shown on or near the Border are Galloway, Tweeddale,

Northumberland and Weardale.

10

Cf. G. W. S. Barrow, The Kingdom of the Scots, 2nd edn (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 136–8.

11

Moore, Lands of the Scottish Kings, p. 59.

12

Below, Chapter 7, p. 312.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 235M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 235 4/3/10 16:12:584/3/10 16:12:58