Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

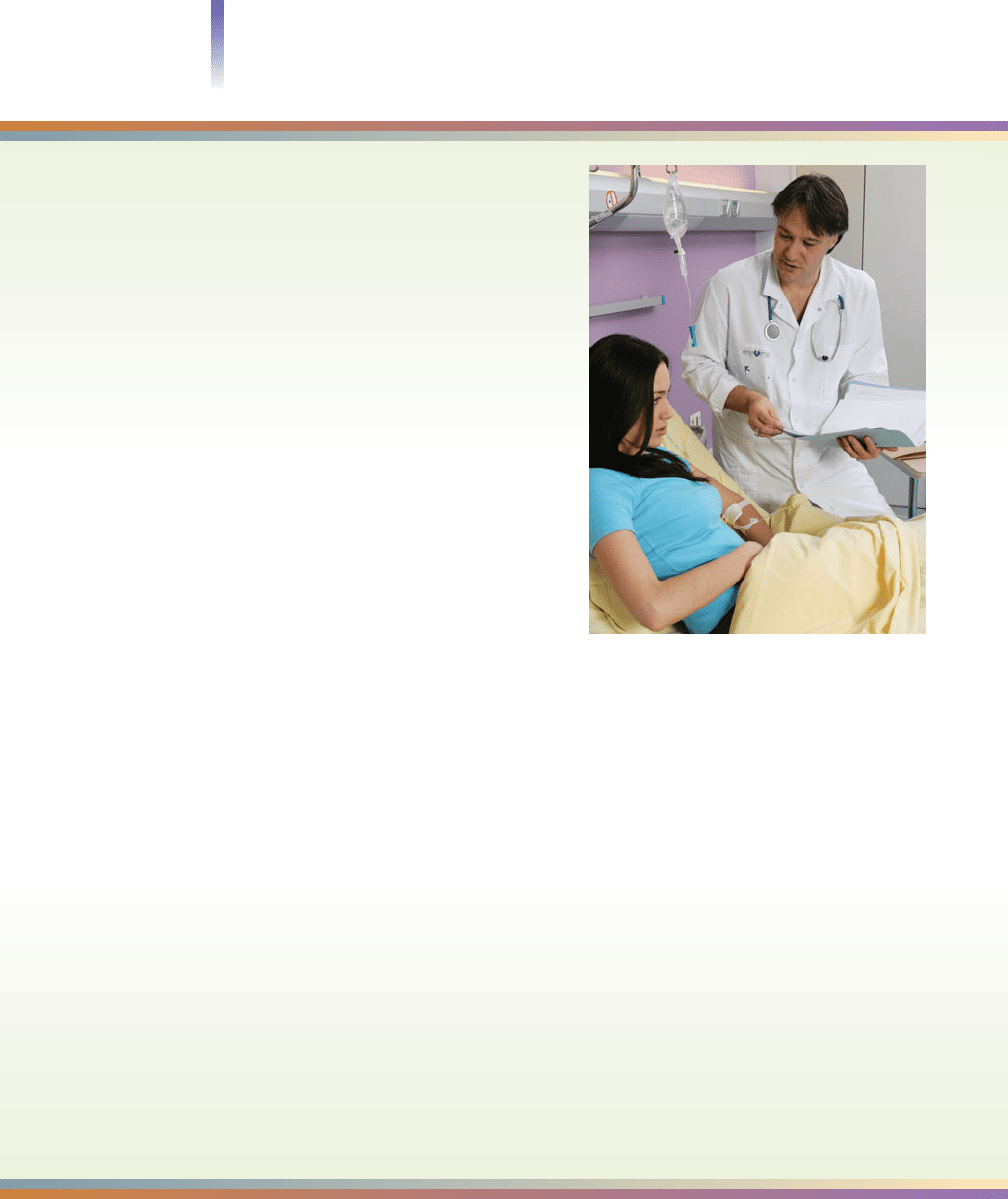

researchers measured the amount of time that surgeons kept patients on the heart-

lung machine while they operated. They were surprised to learn that women spent less

time on the machine than men. This indicated that the surgery was not more difficult

to perform on women.

As the researchers probed, a surprising answer unfolded: unintended sexual discrim-

ination. When women complained of chest pains, their doctors took them only one

tenth as seriously as when men made the same complaints. How do we know this? Doc-

tors were ten times more likely to give men exercise stress tests and radioactive heart

scans. They also sent men to surgery on the basis of abnormal stress tests, but they

waited until women showed clear-cut symptoms of heart disease before sending them

to surgery. Patients who have surgery after heart disease is more advanced are more

likely to die during and after heart surgery.

Although these findings have been publicized among physicians, the problem con-

tinues (Jneid et al. 2008). Perhaps as more women become physicians, the situation

will change, since female doctors are more sensitive to women’s health problems. For ex-

ample, they are more likely to order Pap smears and mammograms (Lurie et al. 1993).

In addition, as more women join the faculties of medical schools, we can expect that

women’s health problems will receive more attention in the training of physicians. Even

this might not do it, however, as no one knows how stereotyping of the sexes produces

this deadly discrimination, and women, too, hold our cultural stereotypes.

In contrast to unintentional sexism in heart surgery, there is a type of surgery that is a

blatant form of discrimination against women. This is the focus of the Down-to-Earth

Sociology box on the next page.

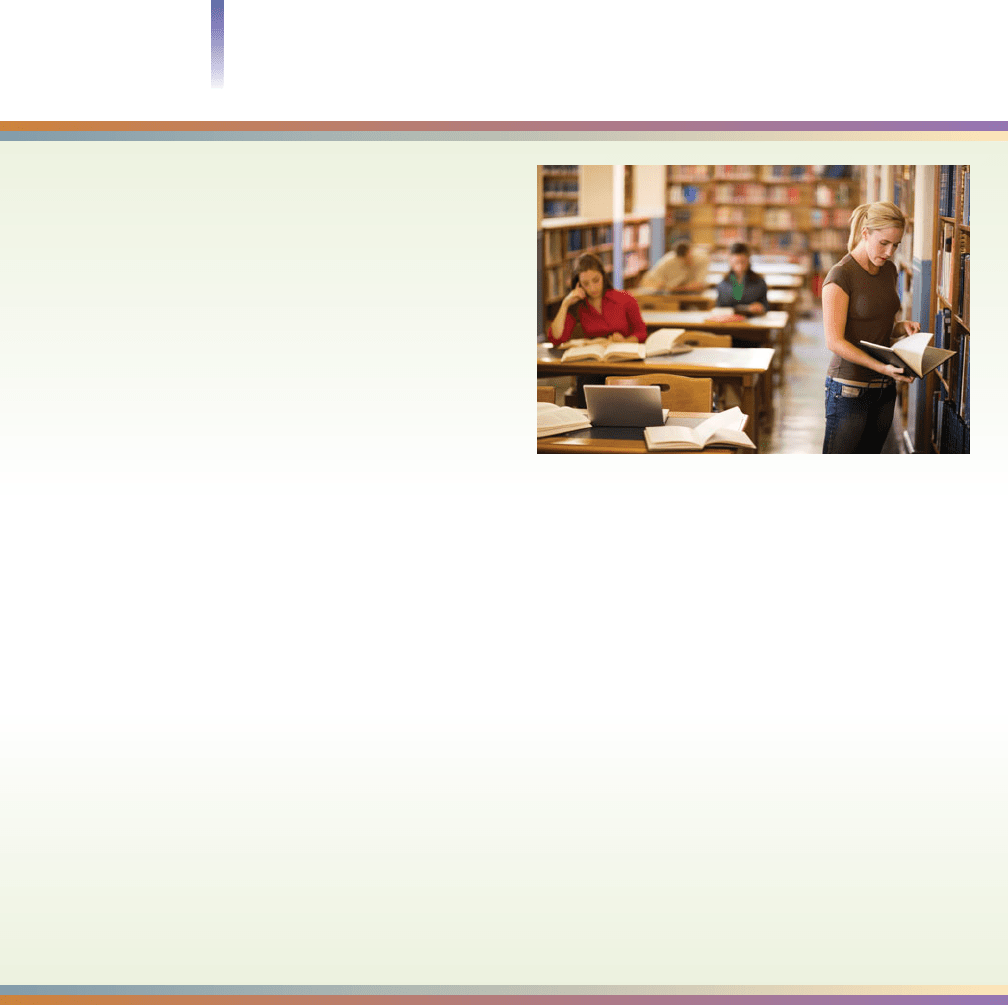

Gender Inequality in Education

To catch a glimpse of the past can give us a context for interpreting

and appreciating the present. In many instances, as we saw in

the box on women and smoking on page 308, change has

been so extensive that the past can seem like it is from a

different planet. So it is with education. Until 1832,

women were not even allowed to attend college with

men. When women were admitted to colleges attended

by men—first at Oberlin College in Ohio—they had

to wash the male students’ clothing, clean their rooms,

and serve them their meals (Flexner 1971/1999).

Female organs were a special focus of concern

for the men who controlled education. They

said that these organs dominated women’s

minds, making them less qualified than men

for higher education. These men viewed men-

struation as a special obstacle to women’s suc-

cess in education. It made women so feeble

that they could hardly continue with their

schooling, much less anything else in life. Here is

how Dr. Edward Clarke, of Harvard University,

put it:

A girl upon whom Nature, for a limited period and for a

definite purpose, imposes so great a physiological task, will

not have as much power left for the tasks of school, as the boy of

whom Nature requires less at the corresponding epoch. (Andersen

1988)

Because women are so much weaker than men, Clarke urged

them to study only one-third as much as young men. And, of

course, in their weakened state, they were advised to not study at all

during menstruation.

Gender Inequality in the United States 311

From grade school through college,

male sports have been emphasized,

and women’s sports underfunded.

Due to federal laws (Title IX),

the funding gap has closed

considerably, and there is an

increasing emphasis on

women’s accomplishments in

sports. Shown here are U. S. A.’s

Mia Hamm (L) and Brazil’s

Elaine Moura, outstanding

soccer players.

312 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

Cold-Hearted Surgeons

and Their Women Victims

S

ociologist Sue Fisher (1986), who did participant

observation in a hospital, was surprised to hear

surgeons recommend total hysterectomy (removal

of both the uterus and the ovaries) when no cancer was

present. When she asked why, the male doctors ex-

plained that the uterus and ovaries are “potentially dis-

ease producing.” They also said that these organs are

unnecessary after the childbearing years, so why not re-

move them? Doctors who reviewed hysterectomies

confirm this bias: Three out of four of these surgeries

are, in their term, inappropriate (Broder et al. 2000).

Greed is a powerful motivator in many areas of so-

cial life, and it rears its ugly head in surgical sexism. Sur-

geons make money when they do hysterectomies, and

the more of them that they do, the more money they

make. Since women, to understate the matter, are reluc-

tant to part with these organs, surgeons find that they

have to “sell” this operation. As you read how one resi-

dent explained the “hard sell” to sociologist Diana

Scully (1994), you might think of a used car salesperson:

You have to look for your surgical procedures; you have

to go after patients. Because no one is crazy enough to

come and say,“Hey, here I am. I want you to operate on

me.” You have to sometimes convince the patient that she

is really sick—if she is, of course [laughs], and that she is

better off with a surgical procedure.

Used-car salespeople would love to have the powerful

sales weapon that these surgeons have at their disposal:

To “convince” a woman to have this surgery, the doctor

puts on a serious face and tells her that the examination

has turned up fibroids in her uterus—and they might turn

into cancer. This statement is often sufficient to get the

woman to buy the surgery. She starts to picture herself

lying at death’s door, her sorrowful family gathered at her

death bed. Then the used car salesperson—I mean,

the surgeon—moves in to clinch the sale. Keeping a seri-

ous face and emitting an “I-know-how-you-feel” look, the

surgeon starts to make arrangements for the surgery.

What the surgeon withholds is the rest of the truth—

that a lot of women have fibroids, that fibroids usually do

not turn into cancer, and that the patient has several al-

ternatives to surgery.

In case it is difficult for someone to see how this is

sexist, let’s change the context just a little. Let’s suppose

that there are female surgeons whose income depends

on their selling a specialized operation. To sell it, they

systematically suggest to older men that they get

castrated—since “that organ is no longer necessary, and

it might cause disease.”

For Your Consideration

Hysterectomies are now so common that one of three

U.S. women eventually has her uterus surgically re-

moved (Whiteman et al. 2008). Why do you think that

surgeons are so quick to operate? How can women find

alternatives to surgery?

Down-to-Earth Sociology

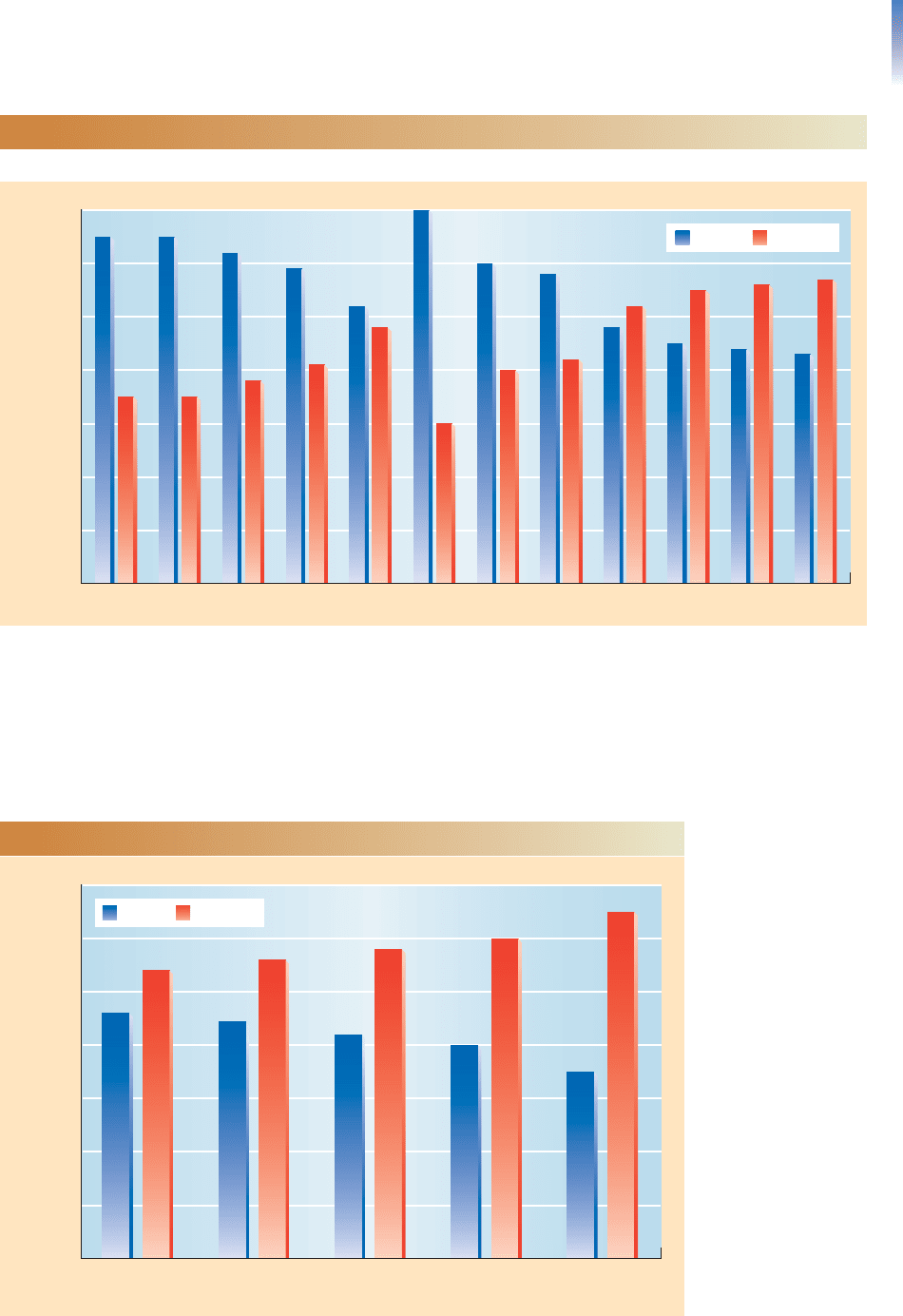

Like out-of-fashion clothing, these ideas were discarded, and women entered college in

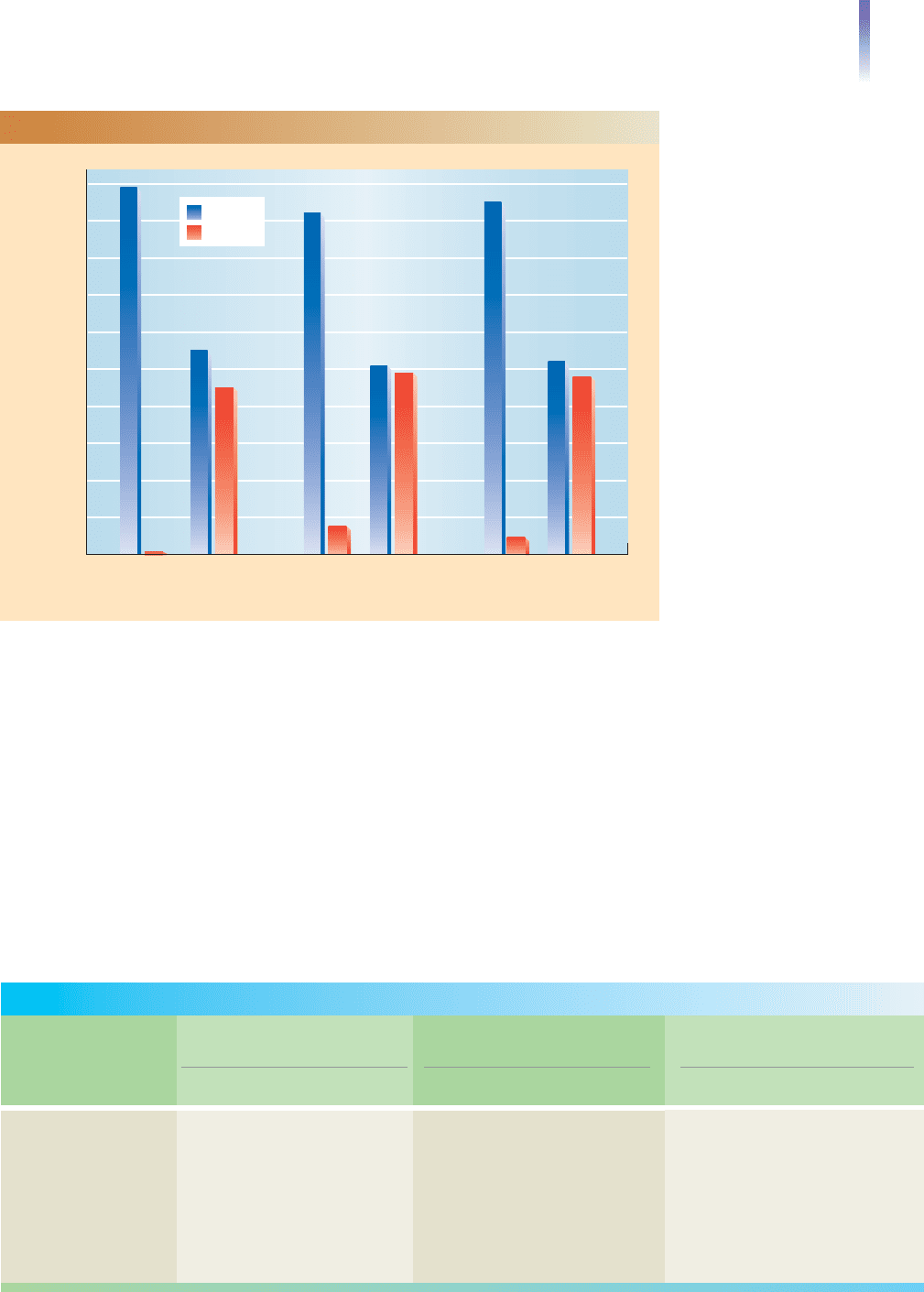

growing numbers. As Figure 11.2 on the next page shows, by 1900 one-third of college stu-

dents were women. The change has been so extensive that 56 percent of today’s college

students are women. This overall average differs with racial–ethnic groups, as you can see

from Figure 11.3 on the next page. African Americans have the fewest men relative to

women, and Asian Americans the most. As another indication of how extensive the change

is, women now earn 57 percent of all bachelor’s degrees and 60 percent of all master’s

degrees (Statistical Abstract 2011:Table 295). As discussed in the Down-to-Earth Sociology

box on page 314, it might be time for affirmative action for men.

Gender Inequality in the United States 313

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Percentage

70%

1900

65

35

1910

65

35

1920

62

38

1930

59

41

1940

52

48

1950*

70

30

1960

60

40

1970

58

42

1980

48

52

1990

45

55

2000

44

56

2010**

43

57

Women

Men

FIGURE 11.2 Changes in College Enrollment, by Sex

What percentages of U.S. college students are female and male?

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 1938:Table 114; 1959:Table 158; 1991:Table 261;

2011:Table 275.

0%

10%

20%

30%

50%

40%

60%

Percentage

70%

Whites

56

44

Latinos

58

42

African

Americans

65

35

Asian

Americans

54

46

Native

Americans

60

40

Women

Men

FIGURE 11.3 College Students, by Sex and Race–Ethnicity

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2008:Table 272; 2011:Table 275.

*

This sharp drop in female enrollment occurred when large numbers of male soldiers returned from World War II and

attended college under the new GI Bill of Rights.

**

Projection by U. S. Department of Education 2008.

Note: This figure can be confusing. To read it, ask: What percentage of the group in college are men

or women? (For example, what percentage of Asian American college students are men or women?)

314 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

Affirmative Action for Men?

T

he idea that we might need affirmative action for

men was first proposed by psychologist Judith

Kleinfeld (2002a). Many met this suggestion with

laughter. After all, men dominate societies around the

world, and they have done so for millennia. The discus-

sion in this chapter has shown that as men exercised

that dominance, they also suppressed and harmed

women. To think that men would ever need affirmative

action seems laughable at best.

In contrast to this reaction, let’s pause, step back

and try to see whether the idea has some merit. Look

again at Figures 11.2 and 11.3 on page 313. Do you

see that women have not only caught up with men,

but that they also have passed them up? Do you see

that this applies to all racial–ethnic groups? That this

is not a temporary situation, like lead cars changing

place at the Indy 500, is apparent from the statistics

the government publishes each year. For decades,

women have steadily added to their proportion of

college student enrollment and the degrees they earn.

This accomplishment is laudable, but what about

the men? Why have they fallen behind? With college

enrollment open equally to both men and women, why

don’t enrollment and degrees now match the relative

proportions of women and men in the population (51

percent and 49 percent)? Although no one yet knows

the reasons for this—and there are a lot of sugges-

tions being thrown about—some have begun to con-

sider this a problem in need of a solution. In a first,

Clark University in Massachusetts has begun a support

program for men to help them adjust to their minority

status (Gibbs 2008). I assume that other colleges will

follow, as these totals have serious implications for the

future of society—just as they did when fewer women

were enrolled in college.

For Your Consideration

Do you think that women’s and men’s current college

enrollments and degrees represent something other

than an interesting historical change? Why do you think

that men have fallen behind? Do you think anything

should be done about this imbalance? If so, what? Be-

hind the scenes, so as not to get anyone upset, some

colleges have begun to reject more highly qualified

women to get closer to a male–female balance (Kings-

bury 2007). What do you think about this?

With fewer men than women in college, is it time to consider

affirmative action for men?

Down-to-Earth Sociology

Figure 11.4 on the next page illustrates another major change. From this figure,

you can see how women have increased their share of professional degrees. The great-

est change is in dentistry: In 1970, across the entire United States, only 34 women

earned degrees in dentistry. Today, about 2,000 women become dentists each year. As

you can also see, almost as many women as men now graduate from U.S. medical and

law schools. With the change so extensive and firm, I anticipate that women will soon

outnumber men in earning these professional degrees.

With these extensive changes, it would seem that gender equality has been achieved,

or at least almost so, and in some instances—as with the changed sex ratio in college—

we have a new form of gender inequality. If we look closer, however, we find something

beneath the surface. Underlying these degrees is gender tracking; that is, college de-

grees tend to follow gender, which reinforces male–female distinctions. Here are two

extremes: Men earn 90 percent of the associate degrees in the “masculine” field of con-

struction trades, while women are awarded 90 percent of the associate degrees in the

“feminine” field of library science (Statistical Abstract 2011:Table 297). Because gen-

der socialization gives men and women different orientations to life, they enter college

with gender-linked aspirations. Socialization—not some presumed innate character-

istic—channels men and women into different educational paths.

Gender Inequality in the United States 315

Field Women Women Women MenMen Men

Completion Ratio* (Higher

or Lower Than Expected)Students Enrolled Doctorates Conferred

TABLE 11.1 Doctorates in Science, By Sex

*The formula for the completion ratio is X minus Y divided by Y, where X is the doctorates conferred and Y is the proportion enrolled in a program.

Mathematics 36% 64% 31% 69% ⫺16 ⫹8

Agriculture 49% 51% 42% 58% ⫺14 ⫹13

Biological 56% 44% 49% 51% ⫺13 ⫹16

Physical 32% 68% 28% 72% ⫺13 ⫹6

CS 25% 75% 22% 78% ⫺12 ⫹2

Social 53% 47% 49% 51% ⫺8 ⫹9

Psychology 75% 25% 71% 29% ⫺5 ⫹16

Engineering 23% 77% 22% 79% ⫺4 ⫹3

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Tables 804, 808.

Men

Women

0

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

90%

70%

50%

30%

10%

Percentage

1970

Medicine (M.D.)

8

92

1970

Dentistry (D.D.S., D.M.D.)

1

99

1970

Law (L.L.B., J.D.)

5

95

2006

49

51

2006

45

55

2006

48

52

FIGURE 11.4 Gender Changes in Professional Degrees

Source: By the author. Based on Digest of Education Statistics 2007:Table 269; Statistical Abstract of

the United States 2011:Table 300.

If we follow students into graduate school, we see that with each passing year the propor-

tion of women drops. Table 11.1 below gives us a snapshot of doctoral programs in the sci-

ences. Note how aspirations (enrollment) and accomplishments (doctorates earned) are sex

linked. In five of these doctoral programs, men outnumber women, and in three, women

outnumber men. In all of them, however, women are less likely to complete the doctorate.

If we follow those who earn doctoral degrees to their teaching careers at colleges and uni-

versities, we find gender stratification in rank and pay. Throughout the United States, women

are less likely to become full professors, the highest-paying and most prestigious rank. In

both private and public colleges, professors average more than twice the salary of instructors

(Statistical Abstract 2011:Table 291). Even when women do become full professors, their av-

erage pay is less than that of men who are full professors (AAUP 2009:Table 5).

Gender Inequality in the Workplace

To examine the work setting is to make visible basic relations between men and

women. Let’s begin with one of the most remarkable areas of gender inequality at work, the

pay gap.

The Pay Gap

One of the chief characteristics of the U.S. workforce is a steady growth in the numbers of

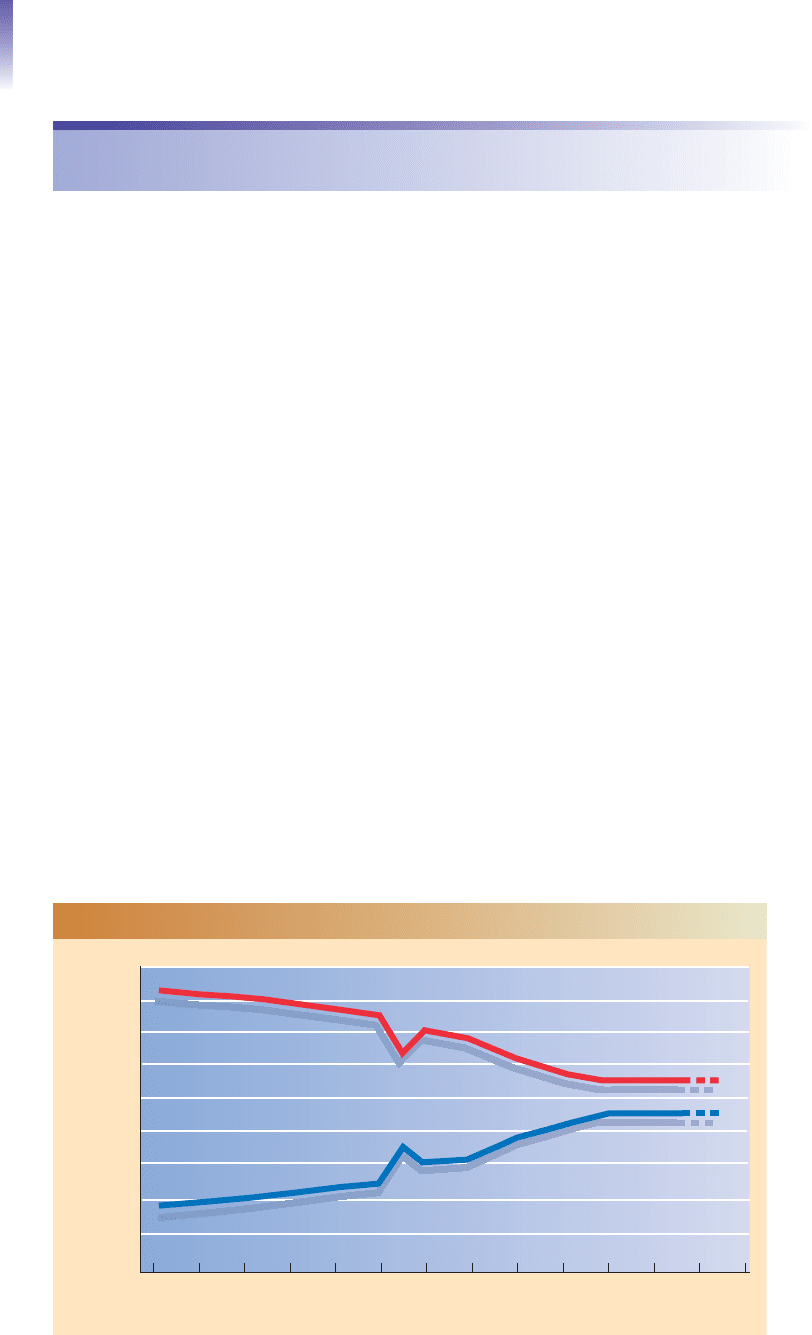

women who work for wages outside the home. Figure 11.5 shows that in 1890 about one of

every five paid workers was a woman. By 1940, this ratio had grown to one of four; by 1960

to one of three; and today it is almost one of two. As shown on this figure, the projections

are that the ratio will remain 55 percent men and 45 percent women for the next few years.

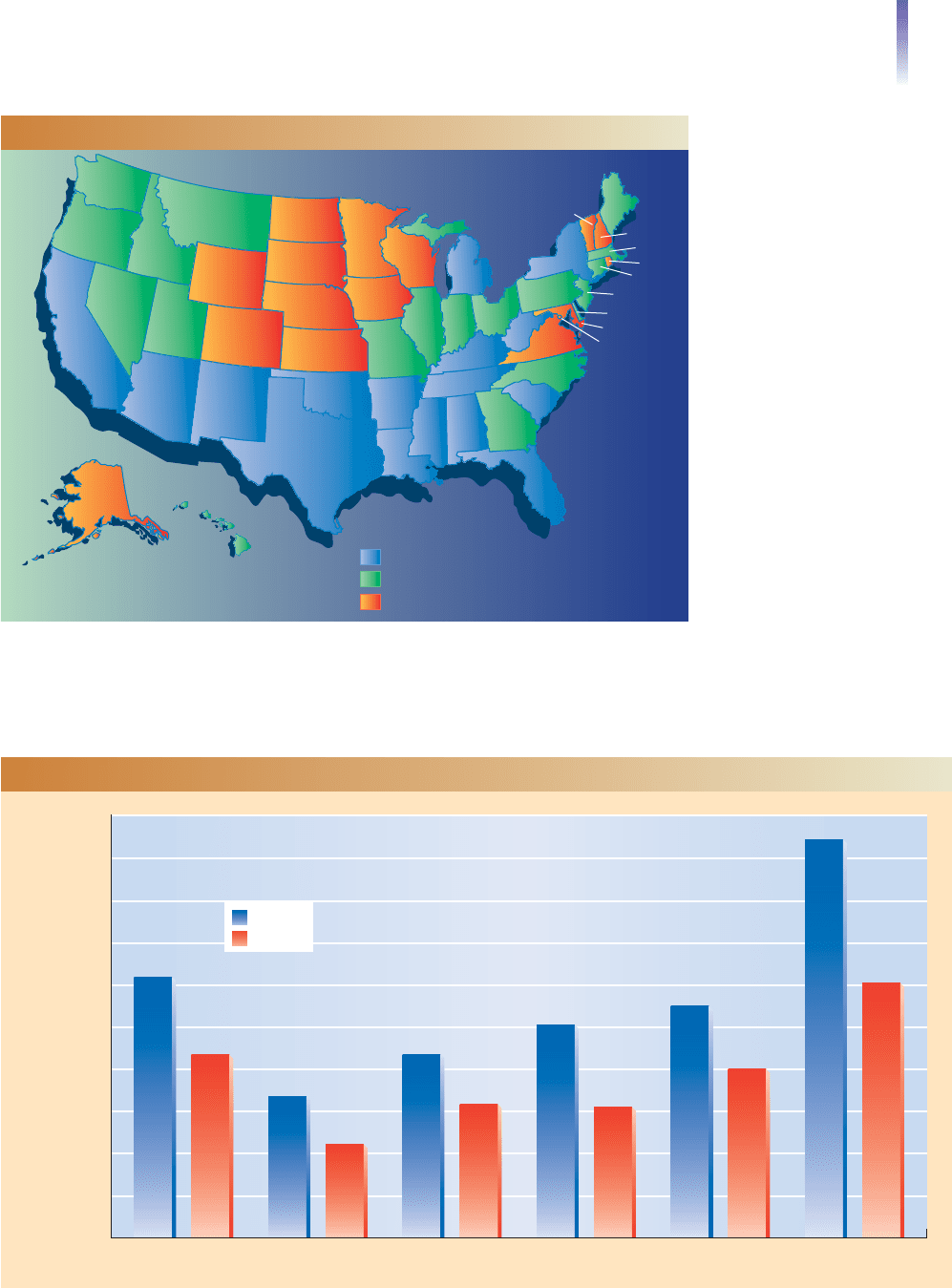

Women who work for wages are not distributed evenly throughout the United States.

From the Social Map on the next page, you can see that where a woman lives makes a dif-

ference in how likely she is to work outside the home. Why is there such a clustering

among the states? The geographical patterns that you see on this map reflect regional-

subcultural differences about which we currently have little understanding.

After college, you might like to take a few years off, travel around Europe, sail the oceans,

or maybe sit on a beach in some South American paradise and drink piña coladas. But chances

are, you are going to go to work instead. Since you have to work, how would you like to

make an extra $650,000 on your job? If this sounds appealing, read on. I’m going to reveal

how you can make an extra $1,356 a month between the ages of 25 and 65. Is this hard to

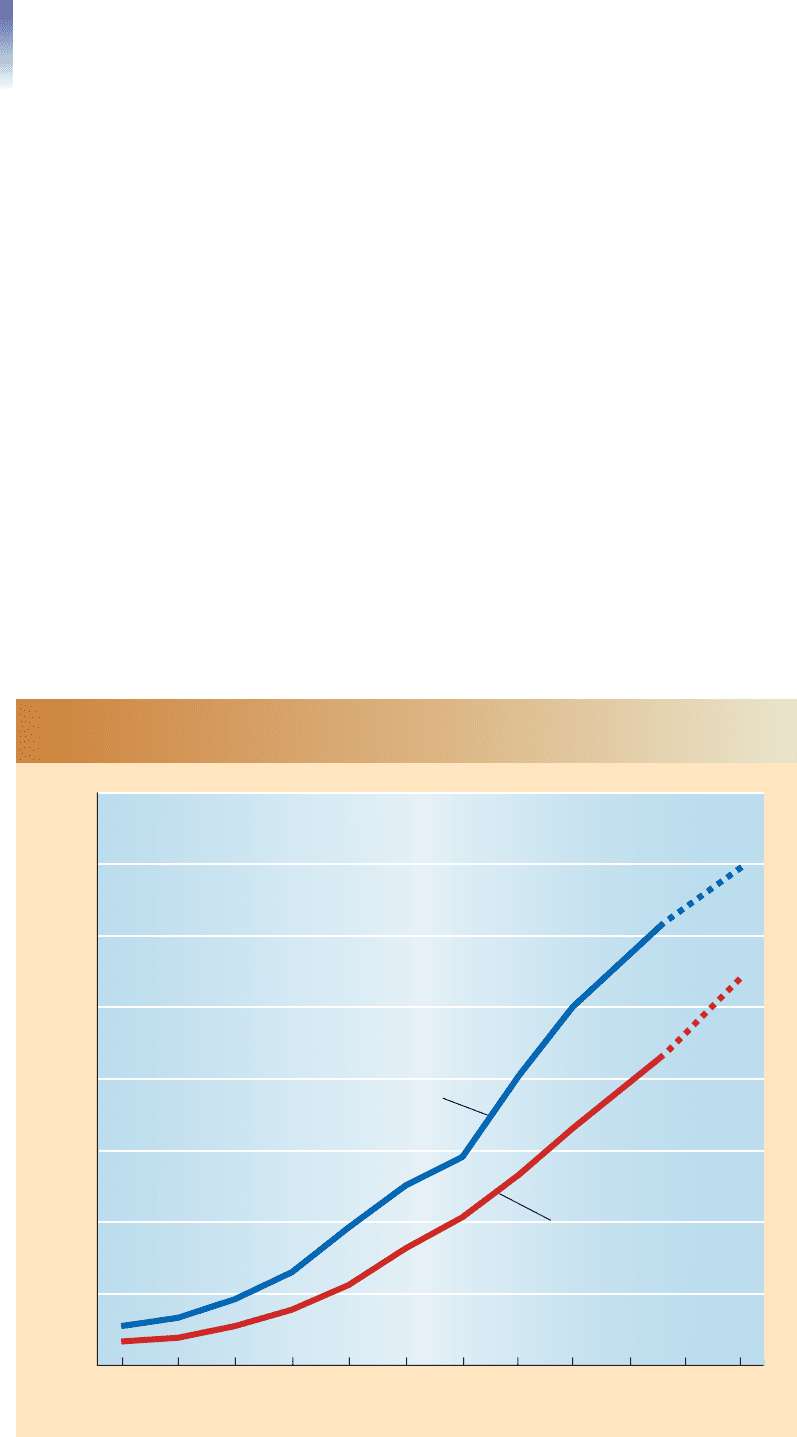

do? Actually, it is simple for some and impossible for others. As Figure 11.7 on the next page

shows, all you have to do is be born a male. If we compare full-time workers, based on cur-

rent differences in earnings, this is how much more money the average male can expect to earn

over the course of his career. Now if you want to boost that monthly difference to $2,482 for

a whopping career total of $1,192,000, be both a male and a college graduate. Hardly any

single factor pinpoints gender discrimination better than these totals. As you can see from Fig-

ure 11.7, the pay gap shows up at all levels of education.

316 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0

Percentage

Men

Women

1890

1900

1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 20202010

Year

90%

FIGURE 11.5 Women’s and Men’s Proportion of the U.S. Labor Force

Sources: By the author. Based on 1969 Handbook on Women Workers, 1969:10; Manpower Report to

the President, 1971:203, 205; Mills and Palumbo, 1980:6, 45; Statistical Abstract of the United States

2011:Table 585.

Note: Pre-1940 totals include women 14 and over: totals for 1940 and after are for women 16

and over. Broken lines are the author’s projections.

0

$10,000

$20,000

$30,000

$40,000

$50,000

$60,000

$70,000

$80,000

$90,000

$1,00,000

Earnings per year

Men

Women

Average of

All Workers

$61,783

$43,305

70%

High School

Dropouts

$33,457

$22,246

High School

Graduates

$43,493

$31,666

Some College,

No Degree

$50,433

$31,019

Associate

Degree

$54,830

$39,935

College

Graduates

$94,206

$60,293

2

66% 73% 71% 73% 64%

Gender Inequality in the Workplace 317

VT

Less than average: 49.2% to 57.8%

Average: 57.9% to 62.9%

More than average: 63.3% to 68.8%

NH

MA

RI

CT

NJ

DE

MD

DC

AK

UT

OH

SC

NC

VA

WA

OR

CA

NV

ID

MT

WY

AZ

NM

CO

ND

SD

NE

KS

OK

TX

MN

IA

MO

AR

LA

WI

IL

KY

TN

MS

AL

GA

FL

IN

MI

WV

PA

NY

ME

HI

What percentage of women are in the workforce?

FIGURE 11.6 Women in the WorkForce

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 593.

Note: At 50.1 percent,West Virginia has the lowest rate of women in the workforce, while

North Dakota, at 69.3 percent, has the highest.

FIGURE 11.7 The Gender Pay Gap, by Education

1

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 702.

1

Full-time workers in all fields.The percentage at the bottom of each red bar

indicates the women’s average percentage of the men’s income.

2

Bachelor’s and all higher degrees, including professional degrees.

The pay gap is so great that U.S. women who work full-time average only 70 percent of

what men are paid. As you can see from Figure 11.8 below, the pay gap used to be even worse.

The gender gap in pay occurs not only in the United States but also in all industrialized nations.

If $1,192,000 in additional earnings isn’t enough, how would you like to make an-

other $166,000 extra at work? If so, just make sure that you are not only a man but also

a tall man. Over their lifetimes, men who are over 6 feet tall average $166,000 more than

men who are 5 feet 5 inches or less (Judge and Cable 2004). Taller women also make

more than shorter women. But even when it comes to height, the gender pay gap persists,

and tall men make more than tall women.

What logic can underlie the gender pay gap? As we just saw, college degrees are gen-

der linked, so perhaps this gap is due to career choices. Maybe women are more likely to

choose lower-paying jobs, such as teaching grade school, while men are more likely to go

into better-paying fields, such as business and engineering. Actually, this is true, and re-

searchers have found that about half of the gender pay gap is due to such factors. And the

balance? It consists of a combination of gender discrimination (Jacobs 2003; Roth 2003)

and what is called the “child penalty”—women missing out on work experience and op-

portunities while they care for children (Hundley 2001; Chaker and Stout 2004).

For college students, the gender gap in pay begins with the first job after graduation.

You might know of a particular woman who was offered a higher salary than most men

in her class, but she would be an exception. On average, men enjoy a “testosterone bonus,”

and employers start them out at higher salaries than women (Fuller and Schoenberger

318 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

$80

70

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Income in Thousands

Year

$40,367

$61,783

$50,241

$43,305

$32,940

70%

Men

$19,173

$24,999

$28,979

$11,159

$16,252

$20,591

$26,547

60%

65%

71%

66%

66%

Women

$5,434

$6,598

$9,184

$12,934

$3,296

$3,816

$5,440

$7,719

61%

58%

59%

60%

FIGURE 11.8 The Gender Gap Over Time: What Percentage of Men’s

Income Do Women Earn?

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 1995:Table 739; 2002:Table 666;

2011:Table 702, and earlier years. Broken lines indicate the author’s estimate.

1991; Harris et al. 2005). Depending on your sex, then, you will

either benefit from the pay gap or be victimized by it.

As a final indication of the extent of the U.S. gender pay gap, con-

sider this. Of the nation’s top 500 corporations (the so-called For-

tune 500), only 12 are headed by women (Kaufman and Hymowitz

2008). The highest number of these positions ever held by women is

13. I examined the names of the CEOs of the 350 largest U.S. cor-

porations, and I found that your best chance to reach the top is to be

named (in this order) John, Robert, James, William, or Charles. Ed-

ward, Lawrence, and Richard are also advantageous names. Amber,

Katherine, Leticia, and Maria apparently draw a severe penalty. Nam-

ing your baby girl John or Robert might seem a little severe, but it

could help her reach the top. (I say this only slightly tongue-in-cheek.

One of the few women to head a Fortune 500 company—before she

was fired and given $21 million severance pay—had a man’s first

name: Carleton Fiorina of Hewlett-Packard. Carleton’s first name is

actually Cara, but knowing what she was facing in the highly com-

petitive business world, she dropped this feminine name to go by her

masculine middle name.)

The Cracking Glass Ceiling

What keeps women from breaking through the glass ceiling,

the mostly invisible barrier that prevents women from reaching

the executive suite? The “pipelines” that lead to the top of a com-

pany are its marketing, sales, and production positions, those

that directly affect the corporate bottom line (Hymowitz 2004;

DeCrow 2005). Men, who dominate the executive suite, stereo-

type women as being good at “support” but less capable than

men of leadership (Belkin 2007). They steer women into human

resources or public relations. Successful projects in these positions are not appreciated

in the same way as those that bring corporate profits—and bonuses for their managers.

Another reason the glass ceiling is so powerful is that women lack mentors—suc-

cessful executives who take an interest in them and teach them the ropes. Lack of a

mentor is no trivial matter, for mentors can provide opportunities to develop leader-

ship skills that open the door to the executive suite (Hymowitz 2007; Mattioli 2008).

The glass ceiling is cracking, however (Hymowitz 2004; Belkin 2007). A look at women

who have broken through reveals highly motivated individuals with a fierce competitive

spirit who are willing to give up sleep and recreation for the sake of career advancement.

Gender Inequality in the Workplace 319

glass ceiling the mostly invis-

ible barrier that keeps women

from advancing to the top lev-

els at work

As the glass ceiling slowly cracks, women are gradually

gaining entry into the top positions in society. In 2009,

Ellen Kullman, shown here, became the first female CEO

of DuPont, a company founded in 1802.

Dilbert

One of the frustrations felt by many women in the labor force is that no matter what they do, they hit a

glass ceiling. Another is that to succeed they feel forced to abandon characteristics they feel are essential

to their self.

They also learn to play by “men’s rules,” developing a style that makes men comfortable.

In addition, women who began their careers twenty to thirty years ago are now running

major divisions within the largest companies (Hymowitz 2004). With this background,

some of these women have begun to emerge as the new CEOs.

When women break through the cracking glass ceiling, they still confront stereotypes

of gender that portray them in less favorable light than men. The women have negotiated

these stereotypes on their way to the top, so they know how to handle them. Occasion-

ally, however, the stereotypes of male dominance lead to humorously awkward situations.

When Nancy Andrews (2007), who became the first female dean of the Duke University

School of Medicine, visited a school in North Carolina, she took her family with her. “As

we entered,” she says, “the school principal vigorously shook my husband’s hand and wel-

comed him, saying, ‘You must be the man of the moment.’ Unfortunately,” she adds, “it

didn’t cross his mind that I might be the ‘woman of the moment.’”

Sexual Harassment—and Worse

Sexual harassment—unwelcome sexual attention at work or at school, which may af-

fect a person’s job or school performance or create a hostile environment—was not rec-

ognized as a problem until the 1970s. Before this, women considered unwanted sexual

comments, touches, looks, and pressure to have sex to be a personal matter.

With the prodding of feminists, women began to perceive unwanted sexual advances

at work and school as part of a structural problem. That is, they began to realize that the

issue was more than a man here or there doing obnoxious things because he was attracted

to a woman; rather, men were using their positions of authority to pressure women to have

sex. Now that women have moved into positions of authority, they, too, have become

sexual harassers (Wayne et al. 2001). With most authority still vested in men, however,

most of the sexual harassers are men.

As symbolic interactionists stress, labels affect our perception. Because we have the

term sexual harassment, we perceive actions in a different light than did our predecessors.

The meaning of sexual harassment is vague and shifting, however, and court cases con-

stantly change what this term does and does not include (Anderson 2006). Originally, sex-

ual desire was an element of sexual harassment, but no longer. This changed when the U.S.

Supreme Court considered the lawsuit of a homosexual who had been tormented by his

supervisors and fellow workers. The Court ruled that sexual desire is not necessary—that

sexual harassment laws also apply to homosexuals who are harassed by heterosexuals while

on the job (Felsenthal 1998). By extension, the law applies to heterosexuals who are sex-

ually harassed by homosexuals.

Central to sexual harassment is the abuse of power, a topic that is explored in the fol-

lowing Thinking Critically section.

320 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

ThinkingCRITICALLY

Sexual Harassment and Rape of Women in the Military

WOMEN RAPED AT WEST POINT! MORE WOMEN RAPED AT THE U.S.AIR FORCE

ACADEMY!

So shrieked the headlines and the TV news teasers. For once, the facts turned out to be just

as startling. Women cadets, who were studying to become officers in the U.S. military, had

been sexually assaulted by their fellow cadets.

And when the women reported the attacks, they were the ones who were punished. The

women found themselves charged with drinking alcohol and socializing with upperclassmen.

sexual harassment the

abuse of one’s position of au-

thority to force unwanted sex-

ual demands on someone