Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Gender Inequality in the Workplace 321

For the most part, the women’s

charges against the men were ig-

nored. The one man who faced a

court martial was acquitted

(Schemo 2003a).

This got the attention of Con-

gress. Hearings were held, and the

commander of the Air Force Acad-

emy was replaced.

A few years earlier, several male

Army sergeants at Aberdeen Proving

Ground in Maryland had been ac-

cused of forcing sex on unwilling fe-

male recruits (McIntyre 1997).The

drill sergeants, who claimed that the

sex was consensual, were found

guilty of rape. One married sergeant,

who pled guilty to having consensual

sex with eleven trainees (adultery is

a crime in the Army), was convicted

of raping another six trainees a total

of eighteen times and was sentenced

to twenty-five years in prison.

The Army appointed a blue-

ribbon panel to investigate sexual

harassment in its ranks.When Sgt.

Major Gene McKinney, the high-

est-ranking of the Army’s 410,000

noncommissioned officers, was

appointed to this committee, former subordinates accused him of sexual harassment

(Shenon 1997). McKinney was relieved of his duties and court-martialed. Found not

guilty of sexual harassment, but guilty of obstruction of justice, McKinney was repri-

manded and demoted. His embittered accusers claimed the Army had sacrificed them for

McKinney.

Rape in the military is not an isolated event. Researchers who interviewed a random

sample of women veterans found that four of five had experienced sexual harassment dur-

ing their military service, and 30 percent had been victims of attempted or completed rape.

Three-fourths of the women who had been raped did not report their assault (Sadler et al.

2003). A study of women graduates of the Air Force Academy showed that 12 percent had

been victims of rape or attempted rape (Schemo 2003b). In light of such findings, the mili-

tary appointed a coordinator of sexual assault at every military base (Stout 2005). Sexual

assaults continue, however (Dreazen 2008).

After the U.S. military was sent to Iraq and Afghanistan, the headlines again screamed

rape, this time in the Persian Gulf. Again, the headlines were right. And once again, Congress

held hearings (Schmitt 2004). With assaults continuing and Congress still putting pressure

on the military, the Army held an emergency summit attended by eighty generals (Dreazen

2008). We’ll have to see how long this cycle of rape followed by hearings followed by rape

repeats itself before adequate reforms are put in place.

For Your Consideration

How can we set up a structure to minimize sexual harassment and rape in the military?

Can we do this and still train men and women together? Can we do this and still have

men and women sleep in the same barracks and on the same ships? Be specific about

the structure you would establish.

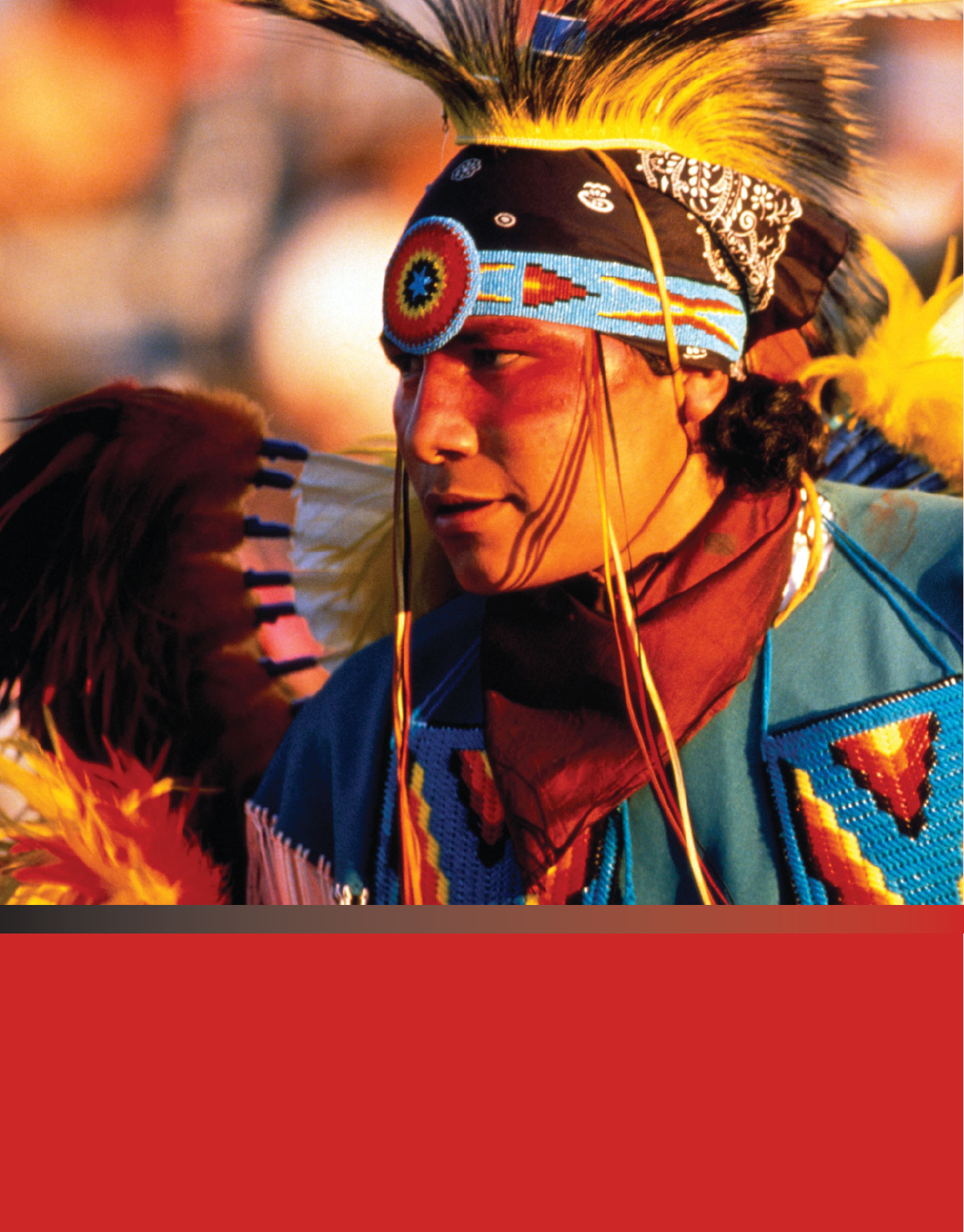

Women in the military being sexually harassed by male soldiers

knows no geographical limits. Shown here is Anjali Gupta, a

Flying Officer in India’s Air Force, who was court martialed for

insubordination after she lodged complaints against a superior

officer.

Gender and Violence

One of the consistent characteristics of violence in the United States—and the world—

is its gender inequality. That is, females are more likely to be the victims of males, not the

other way around. Let’s briefly review this almost one-way street in gender violence as it

applies to the United States.

Violence Against Women

In the Thinking Critically section above, we considered rape in the military; on page

303, we examined violence against women in other cultures; on page 312, we reviewed

a form of surgical violence; and in Chapter 16 we shall review violence in the home.

Here, due to space limitations, we can review only briefly some primary features of

violence.

Forcible Rape. Being raped is a common fear of U.S. women, a fear that is far from

groundless. The U.S. rape rate is 0.59 per 1,000 females (Statistical Abstract 2011:Table

310). If we exclude the very young and women over 50, those who are the least likely to

be rape victims, the rate comes to about 1 per 1,000. This means that 1 of every 1,000

U.S. girls and women between the ages of 12 and 50 is raped each year. Despite this

high number, women are safer now than they were ten and twenty years ago, as the rape

rate has declined.

Although any woman can be a victim of sexual assault—and victims include babies and

elderly women—the typical victim is 16 to 19 years old. As you can see from Table 11.2,

sexual assault peaks at those ages and then declines.

Women’s most common fear seems to be that of strangers—who, appearing as though

from nowhere, abduct and beat and rape them. Contrary to the stereotypes that under-

lie these fears, most victims know their attacker. As you can see from Table 11.3, about

one of three rapes is committed by strangers.

Date (Acquaintance) Rape. What has shocked so many about date rape (also known

as acquaintance rape) are studies showing that it is common (Littleton et al. 2008).

Researchers who used a representative sample of courses to survey the students at Ma-

rietta College, a private school in Ohio, found that 2.5 percent of the women had

been physically forced to have sex (Felton et al. 2001). This was just one college, but

a study using a nationally representative sample of women enrolled in U.S. colleges and

322 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

Relationship

TABLE 11.3 Relationship of Victims and Rapists

Sources: By the author.A ten-year average, based on Statistical Abstract of the

United States 2002:Table 296; 2003:Table 323; 2004-2005:Table 307;

2006:Table 311; 2007:Table 315; 2008:Table 316; 2009:Table 306;

2010:Table 306; 2011:Table 313.

Percentage

Relative 6%

Known Well 33%

Casual 24%

Stranger 34%

Not Reported 3%

Age

TABLE 11.2 Rape Victims

Source: By the author.A ten-year average, based on Statistical Abstract

of the United States 2002:Table 303; 2003:Table 295; 2004:Table 322;

2005:Table 306; 2006:Table 308; 2007:Table 311; 2008:Table 313;

2009:Table 305; 2010:Table 305; 2011:Table 312.

Rate per 1,000 Females

12–15 1.8

16–19 3.2

20–24 2.2

25–34 1.1

35–49 0.7

50–64 0.3

65 and Older 0.08

universities with 1,000 students or more came up with

similar findings. Of these women, 1.7 percent had been

raped during the preceding six months, and another 1.1

percent had been victims of attempted rape (Fisher et al.

2000).

Think about the huge numbers involved. With about 11

million women enrolled in college, 2.8 percent (1.7 plus 1.1)

means that over a quarter of a million college women were vic-

tims of rape or of attempted rape in just the past six months.

(This conclusion assumes that the rate is the same in colleges

with fewer than 1,000 students, which has not been verified.)

Most of the women told a friend what happened, but only 5

percent reported the crime to the police (Fisher et al. 2003).

The most common reason for not reporting was thinking that

the event “was not serious enough.” The next most common

reason was being unsure whether a crime had been commit-

ted. Many women were embarrassed and didn’t want others,

especially their family, to know what happened. Others felt

there was no proof (“It would be my word against his”), feared

reprisal from the man, or feared the police (Fisher et al. 2000).

Sometimes a rape victim feels partially responsible because

she knows the person, was drinking with him, went to his place voluntarily, or invited him

to her place. As a physician who treats victims of date rape said, “Would you feel respon-

sible if someone hit you over the head with a shovel—just because you knew the person?”

(Carpenito 1999).

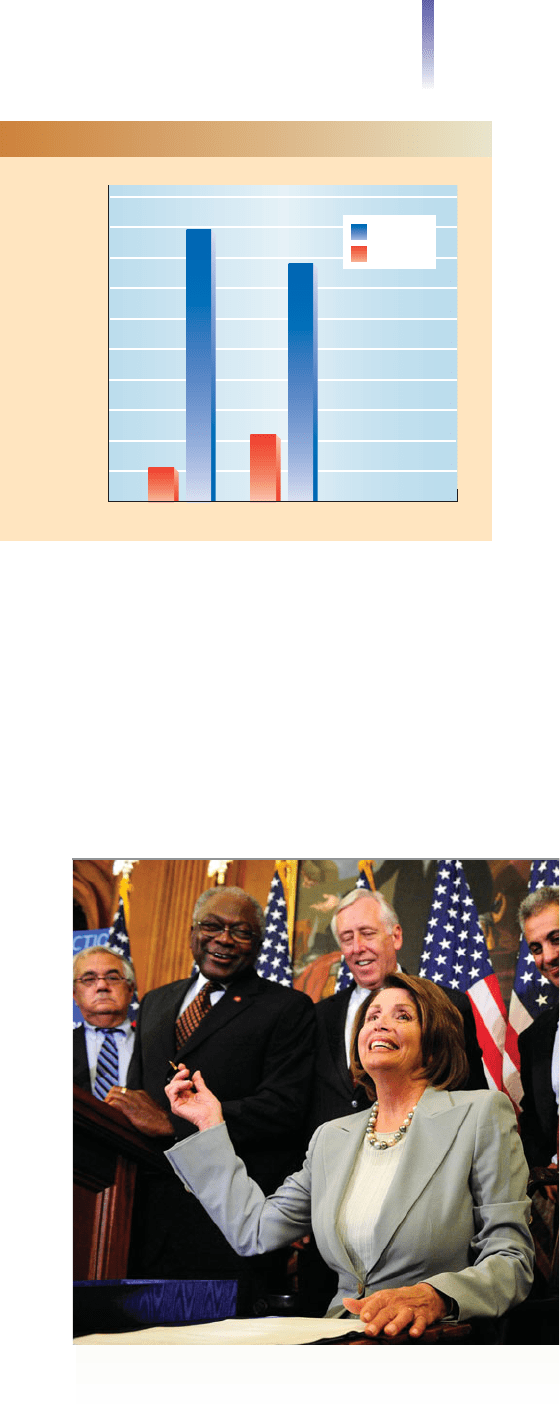

Murder. All over the world, men are more likely than women to be killers. Figure 11.9 il-

lustrates this gender pattern in U.S. murders. Note that although females make up about 51

percent of the U.S. population, they don’t even come close to making up 51 percent of the

nation’s killers. As you can see from this figure, when women are mur-

dered, about 9 times out of 10 the killer is a man.

Violence in the Home. In the family, too, women are the typical

victims. Spouse battering, marital rape, and incest are discussed

in Chapter 16, pages 490–492. Two forms of violence against

women—honor killings and genital circumcision—are discussed

on pages 303 and 306.

Feminism and Gendered Violence. Feminist sociologists have

been especially effective in bringing violence against women to the

public’s attention. Some use symbolic interactionism, pointing out

that to associate strength and virility with violence—as is done in

many cultures—is to promote violence. Others use conflict theory.

They argue that men are losing power, and that some men turn vi-

olently against women as a way to reassert their declining power

and status (Reiser 1999; Meltzer 2002).

Solutions. There is no magic bullet for this problem of gendered

violence, but to be effective, any solution must break the connec-

tion between violence and masculinity. This would require an ed-

ucational program that encompasses schools, churches, homes, and

the media. Given the gun-slinging heroes of the Wild West and

other American icons, as well as the violent messages that are so

prevalent in the mass media, including video games, it is difficult to

be optimistic that a change will come any time soon.

Our next topic, women in politics, however, gives us much more

reason for optimism.

Gender and Violence 323

0

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

90%

70%

50%

30%

10%

The Victims

Percentage

Women

Men

22

78

The Killers

11

89

FIGURE 11.9 Killers and Their Victims

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United

States 2008:Table 318; 2011:Tables 307, 312.

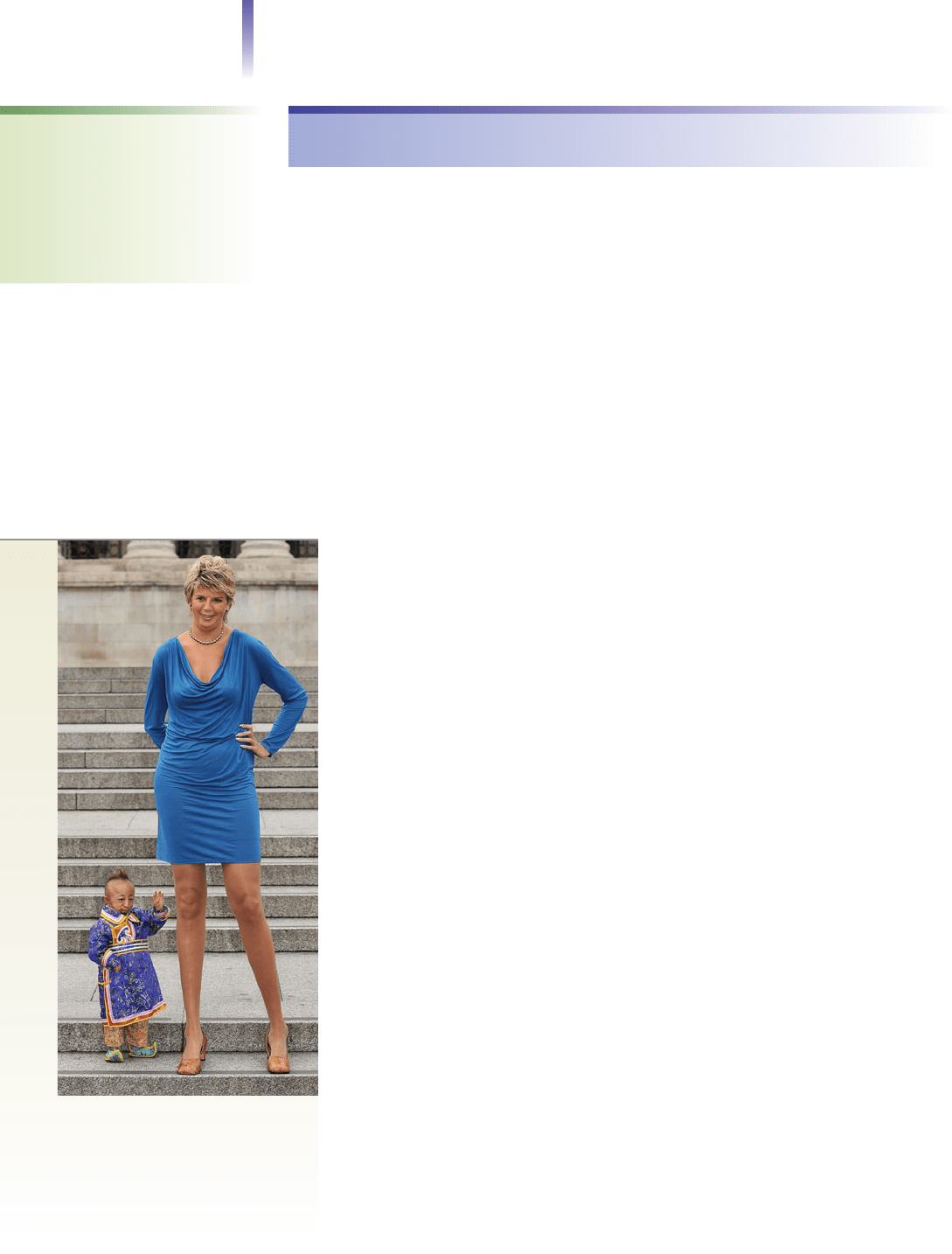

Although women are severely underrepresented in U.S.

politics, the situation is changing, at least gradually. Shown

here is Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the U.S. House of

Representatives, as she signs the financial bailout plan passed

by the House.

The Changing Face of Politics

Women could take over the United States! Think about it. Eight million more women

than men are of voting age, and more women than men vote in U.S. national elec-

tions. As Table 11.4 shows, however, men greatly outnumber women in political of-

fice. Despite the gains women have made in recent elections, since 1789 almost 2,000

men have served in the U.S. Senate, but only 38 women have served, including 17

current senators. Not until 1992 was the first African American woman (Carol Mose-

ley-Braun) elected to the U.S. Senate. No Latina or Asian American woman has yet

been elected to the Senate (National Women’s Political Caucus 1998; Statistical Ab-

stract 2011:Table 405).

Why are women underrepresented in U.S. politics? First, women are still under-

represented in law and business, the careers from which most politicians emerge.

Most women also find that the irregular hours needed to run for office are incompat-

ible with their role as mother. Fathers, in contrast, whose traditional roles are more

likely to take them away from home, are less likely to feel this conflict. Women are

also less likely to have a supportive spouse who is willing to play an unassuming back-

ground role while providing solace, encouragement, child care, and voter appeal.

Finally, preferring to hold on to their positions of power, men have been reluctant

to incorporate women into centers of decision making or to present them as viable

candidates.

These conditions are changing. In 2002, Nancy Pelosi was the first woman to be

elected by her colleagues as minority leader of the House of Representatives. Five years

later, in 2007, they chose her as the first female Speaker of the House. These posts

made her the most powerful woman ever in Congress. Another occurred in 2008 when

Hillary Clinton came within a hair’s breadth of becoming the presidential nominee of

the Democratic party. That same year, Sarah Palin was chosen as the Republican vice-

presidential candidate. We can also note that more women are becoming corporate

executives, and, as indicated in Figure 11.4 (on page 314), more women are also be-

coming lawyers. In these positions, women are traveling more and making statewide

and national contacts. Another change is that child care is increasingly seen as a respon-

sibility of both mother and father. With this generation’s fundamental change in

women’s political participation, it is only a matter of time until a woman occupies the

Oval Office.

324 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

TABLE 11.4 U.S.Women in Political Office

Source: Center for American Women and Politics 2007, 2008a, b.

Number of Offices

Held By Women

Percentage of Offices

Held by Women

National Office

U.S. Senate 17% 17

U.S. House of 17% 74

Representatives

State Office

Governors 16% 8

Lt. Governors 18% 9

Attorneys General 8% 4

Secretaries of State 24% 12

Treasurers 22% 11

State Auditors 12% 6

State Legislators 24% 1,734

Glimpsing the Future—With Hope 325

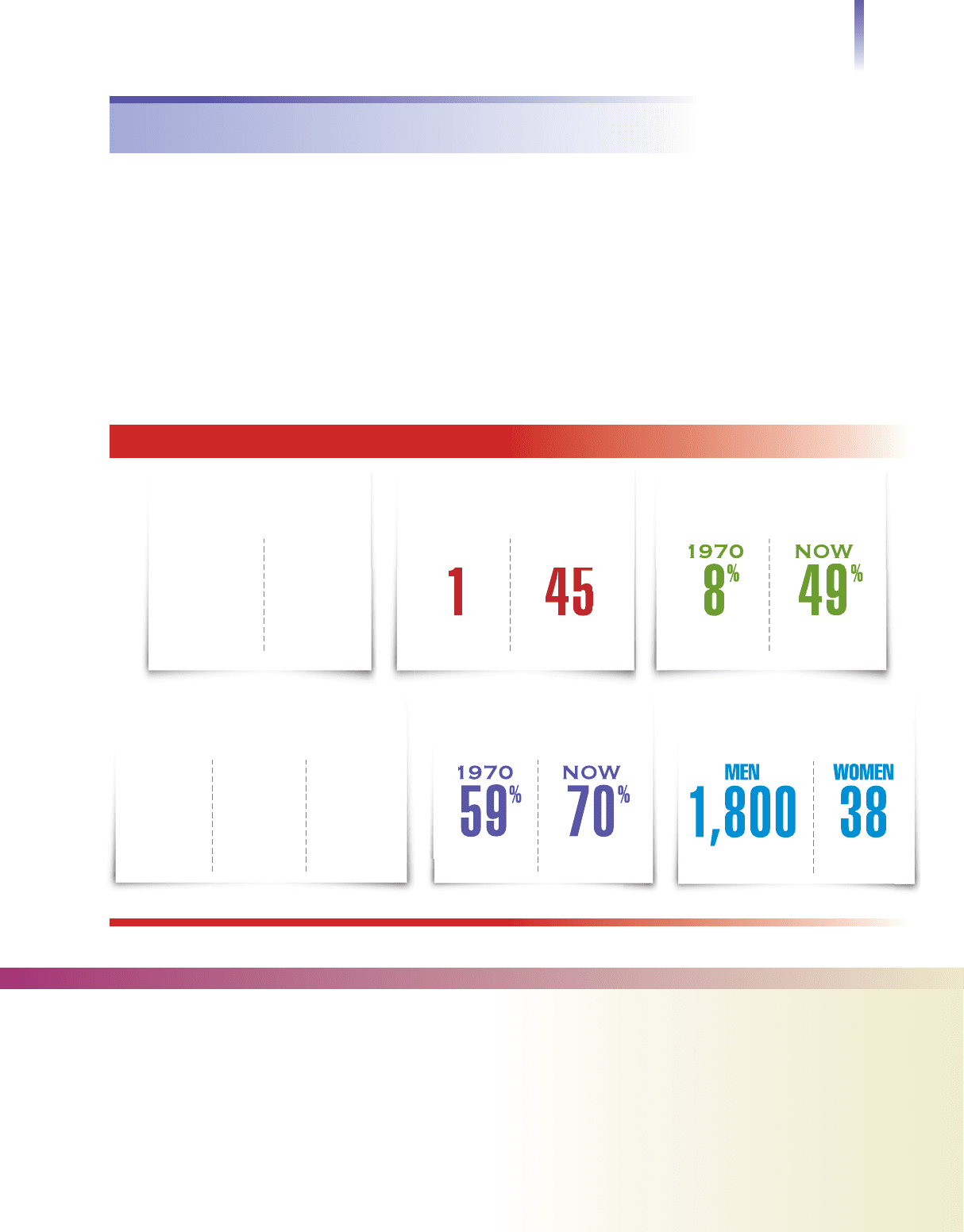

By the Numbers: Then and Now

Glimpsing the Future—With Hope

Women’s fuller participation in the decision-making processes of our social institutions has

shattered stereotypes that tended to limit females to “feminine” activities and push males

into “masculine” ones. As structural barriers continue to fall and more activities are de-

gendered, both males and females will have greater freedom to pursue activities that are

more compatible with their abilities and desires as individuals.

As females and males develop a new consciousness both of their capacities and of their

potential, relationships will change. Distinctions between the sexes will not disappear, but

there is no reason for biological differences to be translated into social inequalities. If cur-

rent trends continue, we may see a growing appreciation of sexual differences coupled with

greater equality of opportunity—which has the potential of transforming society (Gilman

1911/1971; Offen 1990). If this happens, as sociologist Alison Jaggar (1990) observed,

gender equality can become less a goal than a background condition for living in society.

18 9 0

18

1970

38

NOW

45

Women make up this

percentage of the U.S. labor force

%%%

Percentage of dental school

graduates who are women

1970

1

NOW

45

%%

Percentage of medical school

graduates who are women

1970 NOW

OTHER NUMBERS

Number of U.S.

senators since 1789

MEN WOMEN

Wkhi

Percentage of college

students who are women

1970

42

NOW

57

%%

%

%

Percentage of men’s

salary earned by women

1970 NOW

%%

SUMMARY and REVIEW

Issues of Sex and Gender

What is gender stratification?

The term gender stratification refers to unequal access

to property, power, and prestige on the basis of sex. Each

society establishes a structure that, on the basis of sex and

gender, opens and closes doors to its privileges. P. 294.

How do sex and gender differ?

Sex refers to biological distinctions between males and fe-

males. It consists of both primary and secondary sex char-

acteristics. Gender, in contrast, is what a society considers

proper behaviors and attitudes for its male and female

members. Sex physically distinguishes males from females;

gender refers to what people call “masculine” and “femi-

nine.” P. 294.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT Chapter 11

1. What is your position on the “nature versus nurture” (biol-

ogy or culture) debate? What materials in this chapter sup-

port your position?

2. Why do you think that the gender gap in pay exists all over

the world?

3. What do you think can be done to reduce gender inequality?

326 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

Why do the behaviors of males and females differ?

The “nature versus nurture” debate refers to whether dif-

ferences in the behaviors of males and females are caused

by inherited (biological) or learned (cultural) characteris-

tics. Almost all sociologists take the side of nurture. In re-

cent years, however, sociologists have begun to cautiously

open the door to biology. Pp. 294–299.

Gender Inequality in Global Perspective

Is gender stratification universal?

George Murdock surveyed information on tribal societies

and found that all of them have sex-linked activities and

give greater prestige to male activities. Patriarchy, or male

dominance, appears to be universal. Besides work, other

areas of discrimination include education, politics, and vi-

olence. Pp. 299–300.

How did females become a minority group?

The origin of discrimination against females is lost in his-

tory, but the primary theory of how females became a mi-

nority group in their own societies focuses on the physical

limitations imposed by childbirth. Pp. 301–302.

What forms does gender inequality take around

the world?

Its many forms include inequalities in education, politics,

and pay. There is also violence, including female circum-

cision. Pp. 302–306.

Gender Inequality in the United States

Is the feminist movement new?

In what is called the “first wave,” feminists made political

demands for change in the early 1900s—and were met with

hostility, and even violence. The “second wave” began in

the 1960s and continues today. A “third wave” is emerging.

Pp. 307–308.

What forms does gender inequality take in everyday

life, health care, and education?

In everyday life, a lower value is placed on things feminine.

In health care, physicians don’t take women’s health com-

plaints as seriously as those of men, and they exploit women’s

fears, performing unnecessary hysterectomies. In education,

more women than men attend college, but many choose

fields that are categorized as “feminine.” More women than

men also earn college degrees. Women are less likely to com-

plete the doctoral programs in science. Fundamental change

is indicated by the growing numbers of women in law and

medicine. Pp. 308–315.

Gender Inequality in the Workplace

How does gender inequality show

up in the workplace?

All occupations show a gender gap in pay. For college

graduates, the lifetime pay gap runs over a million dollars

in favor of men. Sexual harassment also continues to be

a reality of the workplace. Pp. 316–321.

Gender and Violence

What is the relationship between

gender and violence?

Overwhelmingly, the victims of rape and murder are fe-

males. Female circumcision and honor killing are special

cases of violence against females. Conflict theorists point

out that men use violence to maintain their power and

privilege. Pp. 322–323.

The Changing Face of Politics

What is the trend in gender inequality in politics?

A traditional division of gender roles—women as child

care providers and homemakers, men as workers outside

the home—used to keep women out of politics. Women

continue to be underrepresented in politics, but the

trend toward greater political equality is firmly in place.

P. 324.

Glimpsing the Future—with Hope

How might changes in gender roles

and stereotypes affect our lives?

In the United States, women are more involved in the de-

cision-making processes of our social institutions. Men,

too, are reexamining their traditional roles. New gender

expectations may be developing, ones that allow both

males and females to pursue more individual, less stereo-

typical interests. P. 325.

Summary and Review 327

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

What can you find in MySocLab? www.mysoclab.com

• Complete Ebook

• Practice Tests and Video and Audio activities

• Mapping and Data Analysis exercises

• Sociology in the News

• Classic Readings in Sociology

• Research and Writing advice

Where Can I Read More on This Topic?

Suggested readings for this chapter are listed at the back of this book.

12

Chapter

Race and Ethnicity

magine that you are an African American

man living in Macon County, Alabama, during

the Great Depression of the 1930s. Your home is a little

country shack with a dirt floor. You have no electricity or

running water. You never finished grade school, and you make a

living, such as it is, by doing

odd jobs. You haven’t been

feeling too good lately, but

you can’t afford a doctor.

Then you hear incredible

news. You rub your eyes in

disbelief. It is just like winning the lottery! If you join Miss Rivers’

Lodge (and it is free to join), you will get free physical examinations

at Tuskegee University for life. You will even get free rides to and

from the clinic, hot meals on examination days, and a lifetime of

free treatment for minor ailments.

You eagerly join Miss Rivers’ Lodge.

After your first physical examination, the doctor gives you the

bad news. “You’ve got bad blood,” he says. “That’s why you’ve been

feeling bad. Miss Rivers will give you some medicine and schedule

you for your next exam. I’ve got to warn you, though. If you go to

another doctor, there’s no more free exams or medicine.”

You can’t afford another doctor anyway. You are thankful for

your treatment, take your medicine, and look forward to the next

trip to the university.

What has really happened? You have just become part of what

is surely slated to go down in history as one of the most callous ex-

periments of all time, outside of the infamous World War II Nazi

and Japanese experiments. With heartless disregard for human life,

the U.S. Public Health Service told 399 African American men that

they had joined a social club and burial society called Miss Rivers’

Lodge. What the men were not told was that they had syphilis, that

there was no real Miss Rivers’ Lodge, that the doctors were just

using this term so they could study what happened when syphilis

went untreated. For forty years, the “Public Health Service” allowed

these men to go without treatment for their syphilis—and kept

testing them each year—to study the progress of the disease. The

“public health” officials even had a control group of 201 men who

were free of the disease ( Jones 1993).

By the way, the men did receive a benefit from “Miss Rivers

Lodge,” a free autopsy to determine the ravages of syphilis on their

bodies.

I

You have just become part

of one of the most callous

experiments of all time.

329

Idaho

Laying the Sociological Foundation

As unlikely as it seems, this is a true story. It really did happen. Seldom do race and eth-

nic relations degenerate to this point, but reports of troubled race relations surprise

none of us. Today’s newspapers and TV news shows regularly report on racial prob-

lems. Sociology can contribute greatly to our understanding of this aspect of social

life—and this chapter may be an eye-opener for you. To begin, let’s consider to what

extent race itself is a myth.

Race: Myth and Reality

With its more than 6.5 billion people, the world offers a fascinating variety of human

shapes and colors. People see one another as black, white, red, yellow, and brown. Eyes

come in shades of blue, brown, and green. Lips are thick and thin. Hair is straight, curly,

kinky, black, blonde, and red—and, of course, all shades of brown.

As humans spread throughout the world, their adaptations to diverse climates and

other living conditions resulted in this profusion of complexions, hair textures and

colors, eye hues, and other physical variations. Genetic mutations added distinct char-

acteristics to the peoples of the globe. In this sense, the concept of race—a

group of people with inherited physical characteristics that distinguish it from

another group—is a reality. Humans do, indeed, come in a variety of colors

and shapes.

In two senses, however, race is a myth, a fabrication of the human mind. The

first myth is the idea that any race is superior to others. All races have their geniuses—

and their idiots. As with language, no race is superior to another.

Ideas of racial superiority abound, however. They are not only false but also

dangerous. Adolf Hitler, for example, believed that the Aryans were a superior

race, responsible for the cultural achievements of Europe. The Aryans, he said,

were destined to establish a superior culture and usher in a new world order.

This destiny required them to avoid the “racial contamination” that would

come from breeding with inferior races; therefore, it became a “cultural duty”

to isolate or destroy races that threatened Aryan purity and culture.

Put into practice, Hitler’s views left an appalling legacy—the Nazi slaughter of

those they deemed inferior: Jews, Slavs, gypsies, homosexuals, and people with men-

tal and physical disabilities. Horrific images of gas ovens and emaciated bodies stacked

like cordwood haunted the world’s nations. At Nuremberg, the Allies, flush with vic-

tory, put the top Nazis on trial, exposing their heinous deeds to a shocked world.

Their public executions, everyone assumed, marked the end of such grisly acts.

Obviously, they didn’t. In the summer of 1994 in Rwanda, Hutus slaugh-

tered about 800,000 Tutsis—mostly with machetes (Cowell 2006). A few years

later, the Serbs in Bosnia massacred Muslims, giving us the new term “ethnic

cleansing.” As these events sadly attest, genocide, the attempt to destroy a group

of people because of their presumed race or ethnicity, remains alive and well.

Although more recent killings are not accompanied by swastikas and gas ovens,

the perpetrators’ goal is the same.

The second myth is that “pure” races exist. Humans show such a mixture of

physical characteristics—in skin color, hair texture, nose shape, head shape, eye

color, and so on—that there are no “pure” races. Instead of falling into distinct

types that are clearly separate from one another, human characteristics flow

endlessly together. The mapping of the human genome system shows that hu-

mans are strikingly homogenous, that so-called racial groups differ from one an-

other only once in a thousand subunits of the genome (Angler 2000; Frank

2007). As you can see from the example of Tiger Woods, discussed in the Cul-

tural Diversity box on the next page, these minute gradations make any at-

tempt to draw lines of race purely arbitrary.

330 Chapter 12 RACE AND ETHNICITY

race a group whose inherited

physical characteristics distin-

guish it from other groups

genocide the systematic anni-

hilation or attempted annihila-

tion of a people because of

their presumed race or ethnicity

Humans show remarkable diversity.

Shown here is just one example—He

Pingping, from China, who at 2 feet 4

inches, is the world’s shortest man, and

Svetlana Pankratova, from Russia, who,

according to the Guiness Book of World

Records, is the woman with the longest

legs. Race-ethnicity shows similar

diversity.