Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Summary and Review 291

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

What can you find in MySocLab? www.mysoclab.com

• Complete Ebook

• Practice Tests and Video and Audio activities

• Mapping and Data Analysis exercises

• Sociology in the News

• Classic Readings in Sociology

• Research and Writing advice

Where Can I Read More on This Topic?

Suggested readings for this chapter are listed at the back of this book.

Sex and Gender

11

Chapter

n Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, on Africa’s

northern coast, I met some U.S. college students

and spent a couple of days with them. They wanted to

see the city’s red light district, but I wondered whether it would be

worth the trip. I already had seen other red light districts, including

the unusual one in Amster-

dam where a bronze statue

of a female prostitute lets

you know you’ve entered

the area; the state licenses

the women and men, re-

quiring that they have medical checkups (certificates must be

posted); and the prostitutes add a sales tax to the receipt they give

customers. The prostitutes sit behind lighted picture windows

while customers stroll along the narrow canal side streets and

browse from the outside. Tucked among the brothels are day care

centers, bakeries, and clothing stores. Amsterdam itself is an un-

usual place—you can smoke marijuana in cafes, but not tobacco.

I decided to go with them. We ended up on a wharf that ex-

tended into the Mediterranean. Each side was lined with a row of

one-room wooden shacks, crowded one against the next. In front of

each open door stood a young woman. Peering from outside into

the dark interiors, I could see that each door led to a tiny room

with a well-worn bed.

The wharf was crowded with men who were eyeing the women.

Many of the men wore sailor uniforms from countries that I couldn’t

identify.

As I looked more closely, I could see that some of the women

had runny sores on their legs. Incredibly, with such visible evidence

of their disease, customers still sought them out. Evidently, the

$2 price was too low to resist.

With a sick feeling in my stomach and the desire to vomit,

I kept a good distance between the beckoning women and myself.

One tour of the two-block area was more than sufficient.

Somewhere nearby, out of sight, I knew that there were men

whose wealth derived from exploiting these women who were con-

demned to live short lives punctuated by fear and misery.

I

In front of each open door

stood a young woman.

I could see...a well-worn bed.

293

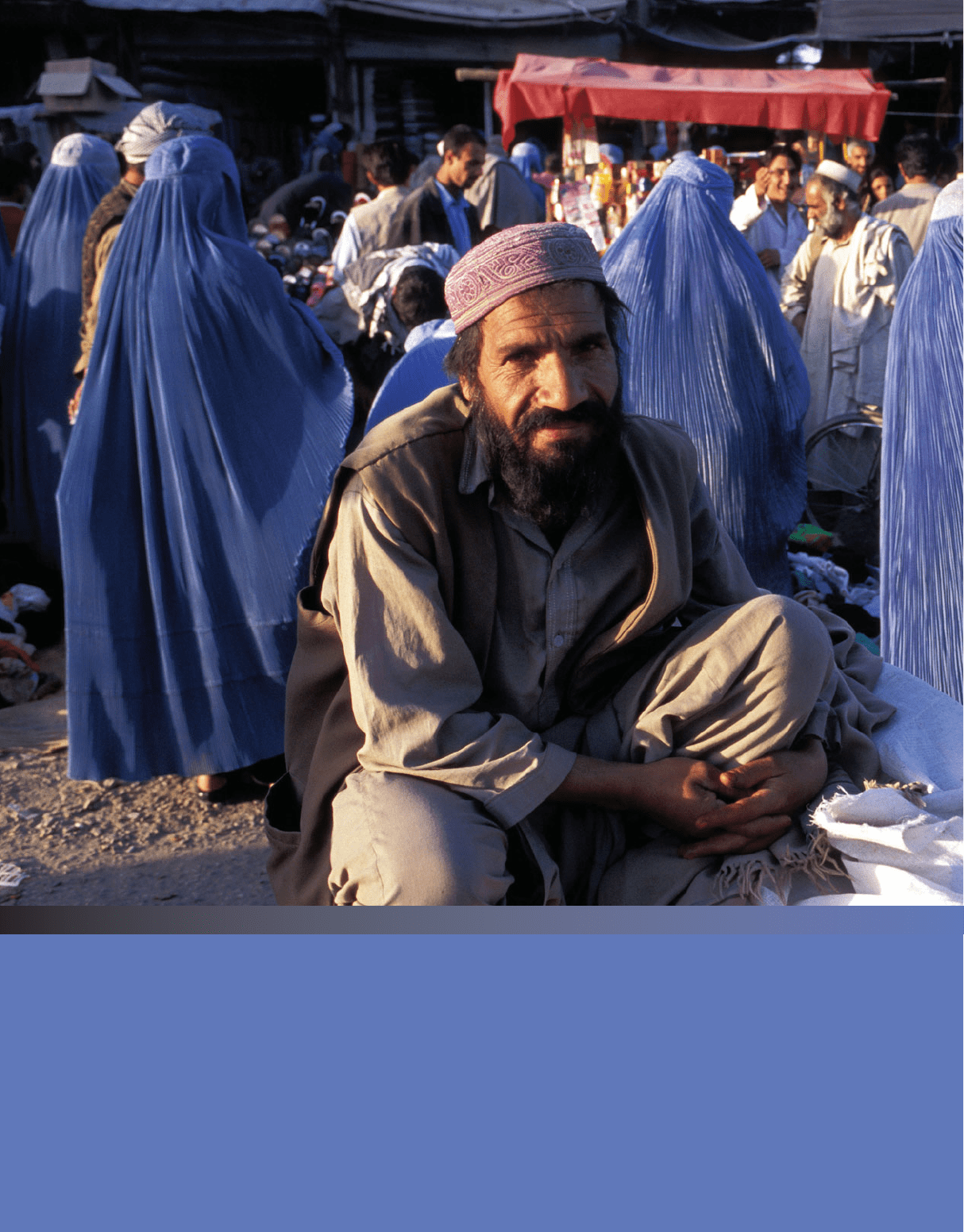

Afghanistan

In this chapter, we examine gender stratification—males’ and females’ unequal access to

property, power, and prestige. Gender is especially significant because it is a master status;

that is, it cuts across all aspects of social life. No matter what we attain in life, we carry

the label male or female. These labels convey images and expectations about how we should

act. They not only guide our behavior but also serve as a basis of power and privilege.

In this chapter’s fascinating journey, we shall look at inequality between the sexes both

around the world and in the United States. We shall explore whether it is biology or cul-

ture that makes us the way we are and review sexual harassment, unequal pay, and vio-

lence against women. This excursion will provide a good context for understanding the

power differences between men and women that lead to situations such as the one de-

scribed in our opening vignette. It should also give you insight into your own experiences

with gender.

Issues of Sex and Gender

When we consider how females and males differ, the first thing that usually comes to

mind is sex, the biological characteristics that distinguish males and females. Primary sex

characteristics consist of a vagina or a penis and other organs related to reproduction.

Secondary sex characteristics are the physical distinctions between males and females that

are not directly connected with reproduction. These characteristics become clearly evident

at puberty when males develop more muscles and a lower voice, and gain more body hair

and height, while females develop breasts and form more fatty tissue and broader hips.

Gender, in contrast, is a social, not a biological characteristic. Gender consists of what-

ever behaviors and attitudes a group considers proper for its males and females. Conse-

quently, gender varies from one society to another. Whereas sex refers to male or female,

gender refers to masculinity or femininity. In short, you inherit your sex, but you learn your

gender as you are socialized into the behaviors and attitudes your culture asserts are ap-

propriate for your sex.

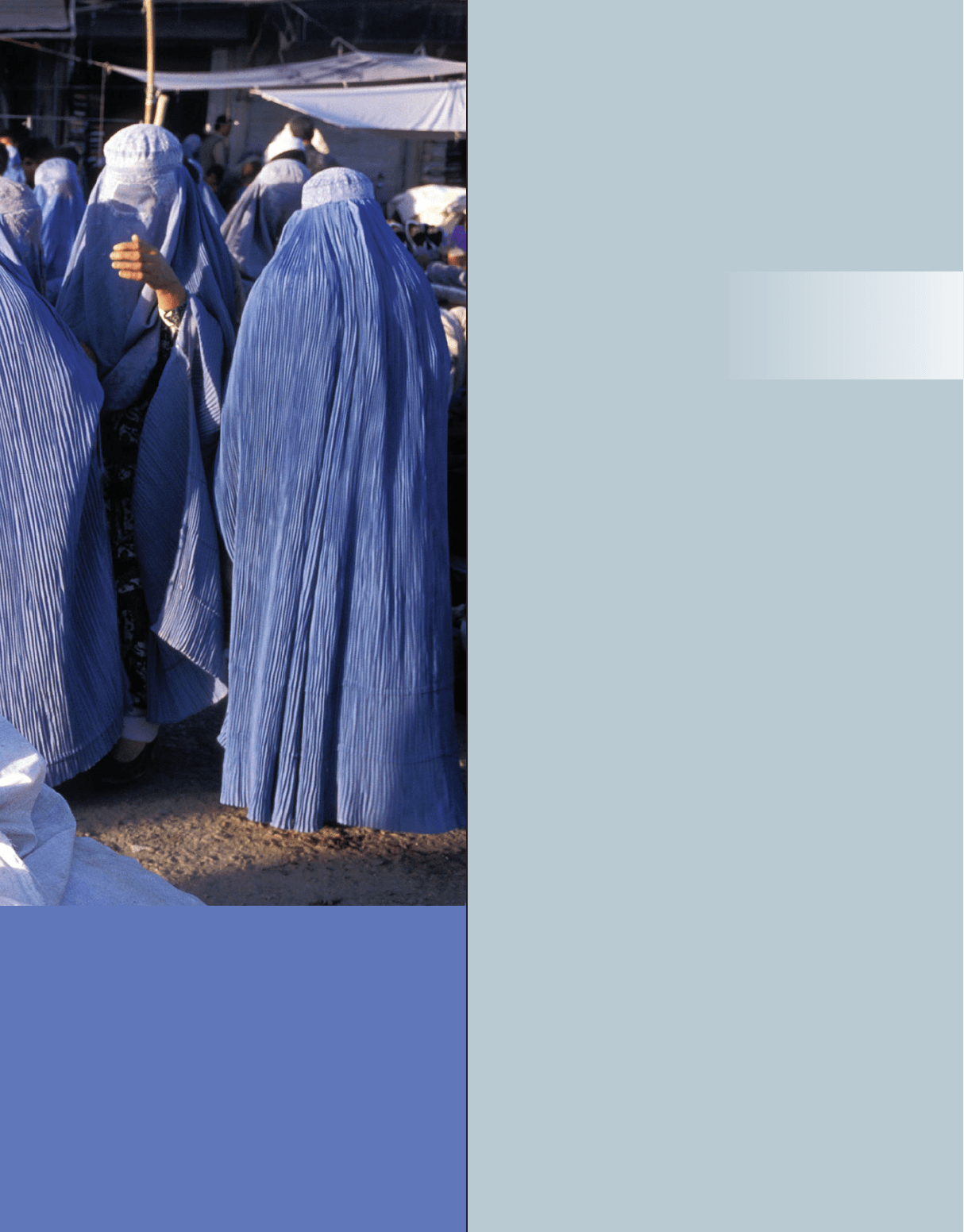

As the photo montage on the next page illustrates, the expectations associated with

gender differ around the world. They vary so greatly that some sociologists suggest that

we replace the terms masculinity and femininity with masculinities and femininities.

The sociological significance of gender is that it is a device by which society controls its mem-

bers. Gender sorts us, on the basis of sex, into different life experiences. It opens and closes

doors to property, power, and even prestige. Like social class, gender is a structural feature

of society.

Before examining inequalities of gender, let’s consider why the behaviors of men and

women differ.

Gender Differences in Behavior: Biology or Culture?

Why are most males more aggressive than most females? Why do women enter “nurtur-

ing” occupations, such as teaching young children and nursing, in far greater numbers

than men? To answer such questions, many people respond with some variation of

“They’re just born that way.”

Is this the correct answer? Certainly biology plays a significant role in our lives. Each

of us begins as a fertilized egg. The egg, or ovum, is contributed by our mother, the sperm

that fertilizes the egg by our father. At the very instant the egg is fertilized, our sex is de-

termined. Each of us receives twenty-three chromosomes from the ovum and twenty-

three from the sperm. The egg has an X chromosome. If the sperm that fertilizes the egg

also has an X chromosome, we become a girl (XX). If the sperm has a Y chromosome, we

become a boy (XY).

That’s the biology. Now, the sociological question is, Does this biological difference

control our behavior? Does it, for example, make females more nurturing and submissive

and males more aggressive and domineering? Almost all sociologists take the side of “nur-

ture” in this “nature versus nurture” controversy, but a few do not, as you can see from

the Thinking Critically section on pages 296–297.

294 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

gender stratification males’

and females’ unequal access to

property, power, and prestige

sex biological characteristics

that distinguish females and

males, consisting of primary and

secondary sex characteristics

gender the behaviors and at-

titudes that a society considers

proper for its males and fe-

males; masculinity or femininity

TibetIndia

Ethiopia Brazil Chile

KenyaJordan

Standards of Gender

Each human group determines its ideas

of “maleness” and “femaleness.” As you

can see from these photos of four

women and four men, standards of

gender are arbitrary and vary from one

culture to another. Yet, in its ethno-

centrism, each group thinks that its

preferences reflect what gender “really”

is. As indicated here, around the world

men and women try to make them-

selves appealing by aspiring to their

group’s standards of gender

Issues of Sex and Gender 295

Mexico

296 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

ThinkingCRITICALLY

Biology Versus Culture—Culture Is the Answer

S

ociologist Cynthia Fuchs Epstein (1988, 1999, 2007) stresses that differences between

the behavior of males and females are solely the result of social factors—specifically,

socialization and social control. Her argument is as follows:

1. The anthropological record shows greater equality between the sexes in the past than

we had thought. In earlier societies, women, as well as men, hunted small game, made

tools, and gathered food. In hunting and gathering societies, the roles of both women

and men are less rigid than those indicated by stereotypes. For example, the Agta and

Mbuti are egalitarian. This proves that hunting and gathering societies exist in which

women are not subordinate to men. Anthropologists claim that in these societies

women have a separate but equal status.

2. The types of work that men and women do in each society are determined not by biology

but by social arrangements. Few people can escape these arrangements, and almost

everyone works within his or her assigned narrow range. This division of work by gen-

der serves the interests of men, and both informal customs and formal laws enforce it.

When these socially constructed barriers are removed, women’s work habits are

similar to those of men.

3. Biology “causes” some human be-

haviors, but they are related to re-

production or differences in body

structure. These differences are rele-

vant for only a few activities, such as

playing basketball or “crawling

through a small space.”

4. Female crime rates are rising in

many parts of the world.This indi-

cates that aggression, which is often

considered a male behavior dictated

by biology, is related instead to so-

cial factors.When social conditions

permit, such as when women be-

come lawyers, they, too, become “ad-

versarial, assertive, and dominant.”

Not incidentally, another form of

this “dominant behavior” is the challenges that women make to the biased views about

human nature proposed by men.

In short, rather than “women’s incompetence or inability to read a legal brief, perform

brain surgery, [or] to predict a bull market,” social factors—socialization, gender dis-

crimination, and other forms of social control—create gender differences in behavior.

Arguments that assign “an evolutionary and genetic basis” to explain differences in the

behaviors of women and men are simplistic.They “rest on a dubious structure of inap-

propriate, highly selective, and poor data, oversimplification in logic and in inappropriate

inferences by use of analogy.”

Cynthia Fuchs Epstein, whose position in the ongoing

“nature versus nurture” debate is summarized here.

Issues of Sex and Gender 297

ThinkingCRITICALLY

Biology Versus Culture—Biology Is the Answer

S

ociologist Steven Goldberg (1974, 1986, 1993, 2003) finds it astonishing that anyone

should doubt “the presence of core-deep differences in males and females, differences

of temperament and emotion we call masculinity and femininity.” Goldberg’s argument—

that it is not environment but inborn differences that “give masculine and feminine direction

to the emotions and behaviors of men and women”—is as follows:

1. The anthropological record shows that all societies for which evidence exists are (or

were) patriarchies (societies in which men-as-a-group dominate women-as-a-group).

Stories about long-lost matriarchies (societies in which women-as-a-group dominate

men-as-a-group) are myths.

2. In all societies, past and present, the highest statuses are associated with men. In every

society, politics is ruled by “hierarchies overwhelmingly dominated by men.”

3. Men dominate societies because they “have a lower threshold for the elicitation of domi-

nance behavior...a greater ten-

dency to exhibit whatever behavior

is necessary in any environment to

attain dominance in hierarchies and

male–female encounters and rela-

tionships.” Men are more willing “to

sacrifice the rewards of other moti-

vations—the desire for affection,

health, family life, safety, relaxation, va-

cation and the like—in order to at-

tain dominance and status.”

4. Just as a 6-foot woman does not

prove the social basis of height, so

exceptional individuals, such as highly

achieving and dominant women, do

not refute “the physiological roots of

behavior.”

In short, there is only one valid in-

terpretation of why every society from that of the Pygmy to that of the Swede associates

dominance and attainment with men. Male dominance of society is “an inevitable resolution

of the psychophysiological reality.” Socialization and social institutions merely reflect—and

sometimes exaggerate—inborn tendencies. Any interpretation other than inborn differ-

ences is “wrongheaded, ignorant, tendentious, internally illogical, discordant with the evi-

dence, and implausible in the extreme.” The argument that males are more aggressive

because they have been socialized that way is equivalent to the claim that men can grow

mustaches because boys have been socialized that way.

To acknowledge this reality is not to defend discrimination against women. Approval or

disapproval of what societies have done with these basic biological differences is not the

issue. The point is that biology leads males and females to different behaviors and attitudes—

regardless of how we feel about this or whether we wish it were different.

Steven Goldberg, whose position in the ongoing “nature

versus nurture” debate is summarized here.

patriarchy a society in which

men as a group dominate

women as a group; authority is

vested in males

matriarchy a society in

which women as a group dom-

inate men as a group; authority

is vested in females

The Dominant Position in Sociology

The dominant sociological position is that we behave the way we do because of social

factors, not biology. Our visible differences of sex do not come with meanings built into

them. Rather, each human group makes its own interpretation of these physical differences

and assigns males and females to separate groups. In these groups, people learn what is

expected of them and are given different access to property, power, prestige, and other priv-

ileges available in their society.

Most sociologists find compelling the argument that if biology were the principal fac-

tor in human behavior, all around the world we would find women behaving in one way

and men in another. In fact, however, ideas of gender vary greatly from one culture to

another—and, as a result, so do male–female behaviors.

Opening the Door to Biology

The matter of “nature” versus “nurture” is not so easily settled, however, and some soci-

ologists acknowledge that biological factors are involved in some human behavior other

than reproduction and childbearing (Udry 2000). Alice Rossi, a feminist sociologist and

former president of the American Sociological Association, has suggested that women are

better prepared biologically for “mothering” than are men. Rossi (1977, 1984) says that

women are more sensitive to the infant’s soft skin and to their nonverbal communica-

tions. She stresses that the issue is not either biology or society. Instead, nature provides

biological predispositions, which are then overlaid with culture.

To see why the door to biology is opening just slightly in sociology, let’s consider a

medical accident and a study of Vietnam veterans.

A Medical Accident. The drama began in 1963, when 7-month-old identical twin boys

were taken to a doctor for a routine circumcision (Money and Ehrhardt 1972). The inept

physician, who was using a heated needle, turned the electric current too high and acci-

dentally burned off the penis of one of the boys. You can imagine the parents’ disbelief—

and then their horror—as the truth sank in.

What can be done in a situation like this? The damage was irreversible. The parents

were told that their boy could never have sexual relations. After months of soul-searching

and tearful consultations with experts, the parents decided that their son should have a

sex-change operation. When he was 22 months old, surgeons castrated the boy, using the

skin to construct a vagina. The parents then gave the child a new name, Brenda, dressed

him in frilly clothing, let his hair grow long, and began to treat him as a girl. Later, physi-

cians gave Brenda female steroids to promote female pubertal growth (Colapinto 2001).

At first, the results were promising. When the twins were 4 years old, the mother said

(remember that the children are biologically identical):

One thing that really amazes me is that she is so feminine. I’ve never seen a little girl so neat

and tidy....She likes for me to wipe her face. She doesn’t like to be dirty, and yet my son is

quite different. I can’t wash his face for anything. ...She is very proud of herself, when she

puts on a new dress, or I set her hair....She seems to be daintier. (Money and Ehrhardt 1972)

About a year later, the mother described how their daughter imitated her while their

son copied his father:

I found that my son, he chose very masculine things like a fireman or a policeman. . . . He

wanted to do what daddy does, work where daddy does, and carry a lunch kit. . . . [My

daughter] didn’t want any of those things. She wants to be a doctor or a teacher. . . . But none

of the things that she ever wanted to be were like a policeman or a fireman, and that sort of

thing never appealed to her. (Money and Ehrhardt 1972)

If the matter were this clear-cut, we could use this case to conclude that gender is de-

termined entirely by nurture. Seldom are things in life so simple, however, and a twist

occurs in this story. Despite this promising start and her parents’ coaching, Brenda did

not adapt well to femininity. She preferred to mimic her father shaving, rather than

her mother putting on makeup. She rejected dolls, favoring guns and her brother’s

298 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

David

Reimer,

whose story

is recounted

here.

toys. She liked rough-and-tumble games and insisted on urinating standing up. Classmates

teased her and called her a “cavewoman” because she walked like a boy. At age 14, she was ex-

pelled from school for beating up a girl who teased her. Despite estrogen treatment, she was

not attracted to boys, and at age 14, in despair over her inner turmoil, she was thinking of sui-

cide. In a tearful confrontation, her father told her about the accident and her sex change.

“All of a sudden everything clicked. For the first time, things made sense, and I under-

stood who and what I was,” the twin said of this revelation. David (his new name) then

had testosterone shots and, later, surgery to partially reconstruct a penis. At age 25, he

married a woman and adopted her children (Diamond and Sigmundson 1997; Colapinto

2001). There is an unfortunate end to this story, however. In 2004, David committed

suicide.

The Vietnam Veterans Study. Time after time, researchers have found that boys and men

who have higher levels of testosterone tend to be more aggressive. In one study, researchers

compared the testosterone levels of college men in a “rowdy” fraternity with those of men in

a fraternity that had a reputation for academic achievement and social responsibility. Men in

the “rowdy” fraternity had higher levels of testosterone (Dabbs et al. 1996). In another study,

researchers found that prisoners who had committed sex crimes and acts of violence against

people had higher levels of testosterone than those who had committed property crimes

(Dabbs et al. 1995). The samples were small, however, leaving the nagging uncertainty that

these findings might be due to chance.

Then in 1985, the U.S. government began a health study

of Vietnam veterans. To be certain that the study was rep-

resentative, the researchers chose a random sample of 4,462

men. Among the data they collected was a measurement of

testosterone. This sample supports earlier studies showing

that men who have higher levels of testosterone tend to be

more aggressive and to have more problems as a conse-

quence. When the veterans with higher testosterone levels

were boys, they were more likely to get in trouble with par-

ents and teachers and to become delinquents. As adults,

they were more likely to use hard drugs, to get into fights,

to end up in lower-status jobs, and to have more sexual part-

ners. Those who married were more likely to have affairs, to

hit their wives, and, it follows, to get divorced (Dabbs and

Morris 1990; Booth and Dabbs 1993).

This makes it sound like biology is the basis for behav-

ior. Fortunately for us sociologists, there is another side to

this research, and here is where social class, the topic of our

previous chapter, comes into play. High-testosterone men

from lower social classes are more likely to get in trouble

with the law, do poorly in school, or mistreat their wives

than are high-testosterone men from higher social classes

(Dabbs and Morris 1990). Social factors such as socializa-

tion, subcultures, life goals, and self-definitions are signif-

icant in these men’s behavior. Discovering how social

factors work in combination with testosterone level, then,

is of great interest to sociologists.

In Sum: The findings are preliminary, but significant and provocative. They indicate that

human behavior is not a matter of either nature or nurture, but of the two working to-

gether. Some behavior that we sociologists usually assume to be due entirely to socialization

is apparently influenced by biology. In the years to come, this should prove to be an excit-

ing—and controversial—area of sociological research. One level of research will be to deter-

mine whether any behaviors are due only to biology. The second level will be to discover the

ways that social factors modify biology. The third level will be, in sociologist Janet Chafetz’s

(1990:30) phrase, to determine how “different” becomes translated into “unequal.”

Issues of Sex and Gender 299

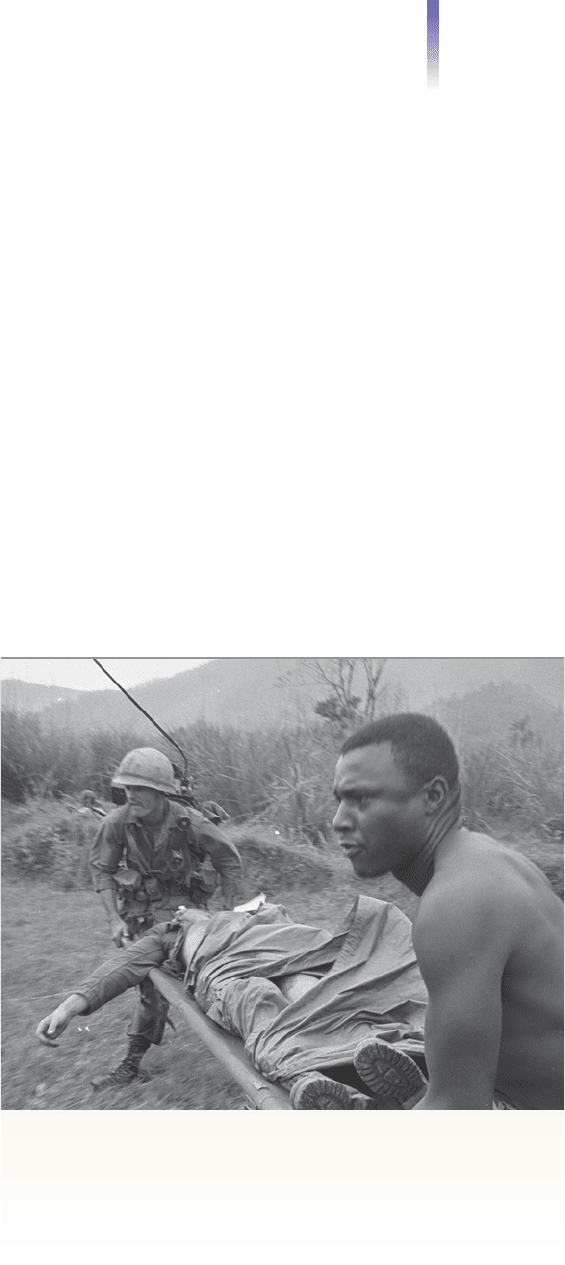

Sociologists study the social factors that underlie human behavior,

the experiences that mold us, funneling us into different directions in

life. The research on Vietnam veterans discussed in the text

indicates how the sociological door is opening slowly to also

consider biological factors in human behavior. This 1966 photo

shows orderlies rushing a wounded soldier to an evacuation

helicopter.

Gender Inequality in Global Perspective

Around the world, gender is the primary division between people. Every society sorts men

and women into separate groups and gives them different access to property, power, and

prestige. These divisions always favor men-as-a-group. After reviewing the historical

record, historian and feminist Gerda Lerner (1986) concluded that “there is not a single

society known where women-as-a-group have decision-making power over men (as a

group).” Consequently, sociologists classify females as a minority group. Because females

outnumber males, you may find this strange. The term minority group applies, however,

because it refers to people who are discriminated against on the basis of physical or cul-

tural characteristics, regardless of their numbers (Hacker 1951). For an overview of gen-

der discrimination in Iran, see the Mass Media in Social Life box on the next page.

How Females Became a Minority Group

Have females always been a minority group? Some analysts speculate that in hunting and

gathering societies, women and men were social equals (Leacock 1981; Hendrix 1994) and

that horticultural societies also had less gender discrimination than is common today

(Collins et al. 1993). In these societies, women may have contributed about 60 percent

of the group’s total food. Yet, around the world, gender is the basis for discrimination.

How, then, did it happen that women became a minority group? Let’s consider the pri-

mary theory that has been proposed.

The Origins of Patriarchy

The major theory of the origin of patriarchy—men dominating society—points to social

consequences of human reproduction (Lerner 1986; Friedl 1990). In early human history,

life was short. To balance the high death rate and maintain the population, women had

to give birth to many children. This brought severe consequences for women. To survive,

an infant needed a nursing mother. With a child at her breast or in her uterus, or one car-

ried on her hip or on her back, women were physically encumbered. Consequently,

around the world women assumed tasks that were associated with the home and child care,

while men took over the hunting of large animals and other tasks that required both

greater speed and longer absences from the base camp (Huber 1990).

As a result, men became dominant. It was the men

who left camp to hunt animals, who made contact with

other tribes, who traded with these groups, and who

quarreled and waged war with them. It was also the

men who made and controlled the instruments of

death, the weapons that were used for hunting and

warfare. It was they who accumulated possessions in

trade and gained prestige by returning to the camp tri-

umphantly, leading captured prisoners or bringing

large animals they had killed to feed the tribe. In con-

trast, little prestige was given to the routine, taken-for-

granted activities of women—who were not perceived

as risking their lives for the group. Eventually, men

took over society. Their sources of power were their

weapons, items of trade, and knowledge gained from

contact with other groups. Women became second-

class citizens, subject to men’s decisions.

Is this theory correct? Remember that the answer lies

buried in human history, and there is no way of testing

it. Male dominance may be the result of some entirely

different cause. For example, anthropologist Marvin

Harris (1977) proposed that because most men are

stronger than most women and survival in tribal groups

300 Chapter 11 SEX AND GENDER

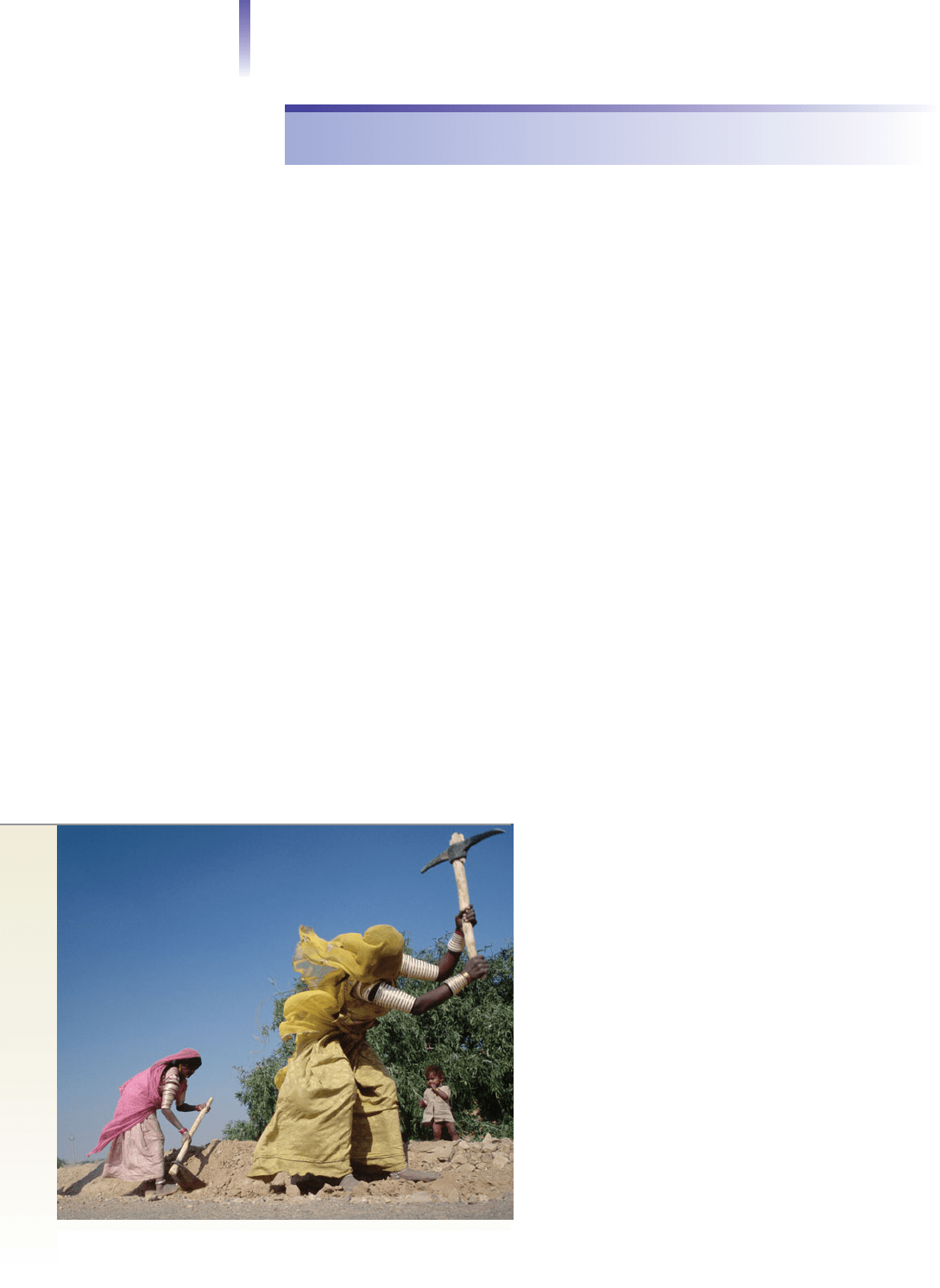

Men’s work? Women’s work? Customs in other societies can blow away

stereotypes. As is common throughout India, these women are working

on road construction.