Hatano Y., Katsumura Y., Mozumder A. (Eds.) Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter - Recent Advances, Applications, and Interfaces

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

880 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

are introduced. The following text discusses RGL detectors designed for applications in accelerator

physics, non-accelerator physics, and medical imaging. These include various phenomena, such

as neutrino physics, “μ → eγ” decay, dark matter search and, for medical imaging applications,

positron emission tomography (PET). Some calorimeters, the time projection chamber (TPC), and

scintillation

detectors are also introduced.

We

have introduced only a few topics, which we found to be unique or pioneering, because of

space limitations. With regard to numerous experimental proposals using RGL detectors, espe-

cially for rare event searches, such as dark matter or neutrinoless double-beta decay, the recent

fast evolution of RGL detectors and related technologies deserve special mention. These are the

particle detection technique by simultaneous observation of ionization and scintillation signals or a

waveform analysis for scintillation signals, VUV photon detection at low temperature, purication

techniques, etc. Furthermore, large detection technologies have been developed, the ICARUS* liq-

uid argon (LAr) detector and the 20t XMASS

†

LXe detector, their estimated volume approaching

the

world annual production volume of Ar and Xe.

The

development of the detectors also produced interesting results in the elds of radiation phys-

ics and chemistry as a by-product. Dark matter searches, for instance, encouraged new, elaborated

measurements in the interaction of very-low-energy ions with condensed media. The atomic colli-

sions in the estimated energy range have been studied almost half a century ago. However, radiation

effects have not been discussed in detail. Slow energy collision is also theoretically quite difcult to

deal with. For example, the Thomas–Fermi model, a major method of dealing with slow ion colli-

sions, becomes uncertain in Xe–Xe collisions below 10 keV (Lindhard etal., 1963). New results that

would be obtained with dark matter searches will give materials to develop a new collision theory

in the extreme low-energy region.

Here, we refer to RGL as Ar, Kr, and Xe, unless otherwise stated. Ionization and scintillation

properties

of He and Ne are different from those of Ar, Kr, and Xe, and are not discussed here.

31.2 basiC properties oF rare gas liQuids For deteCtor media

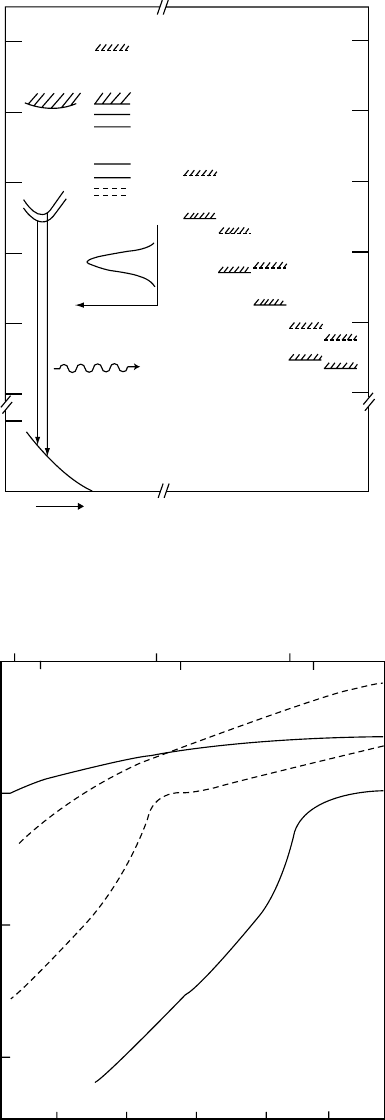

The energy levels in solid argon are shown schematically in Figure 31.1, and those for RGLs are

basically the same. One of the remarkable features in the condensed phase is the existence of the

conduction band. The bandgap energies for LAr and LXe are 14.3 and 9.28eV, respectively, and

are considerably lower than the ionization potentials of 15.75 and 12.13eV, respectively, in the gas

phase. Further, the excitonic levels appear instead of the excited states of atoms (Baldini, 1962;

Beaglehole, 1965; Steinberger and Schnepp, 1967; Asaf and Steinberger, 1971; Laporte etal., 1980),

which

show the exciton mass, m

ex

, to be 1–5 m

e

, where m

e

is the electron mass.

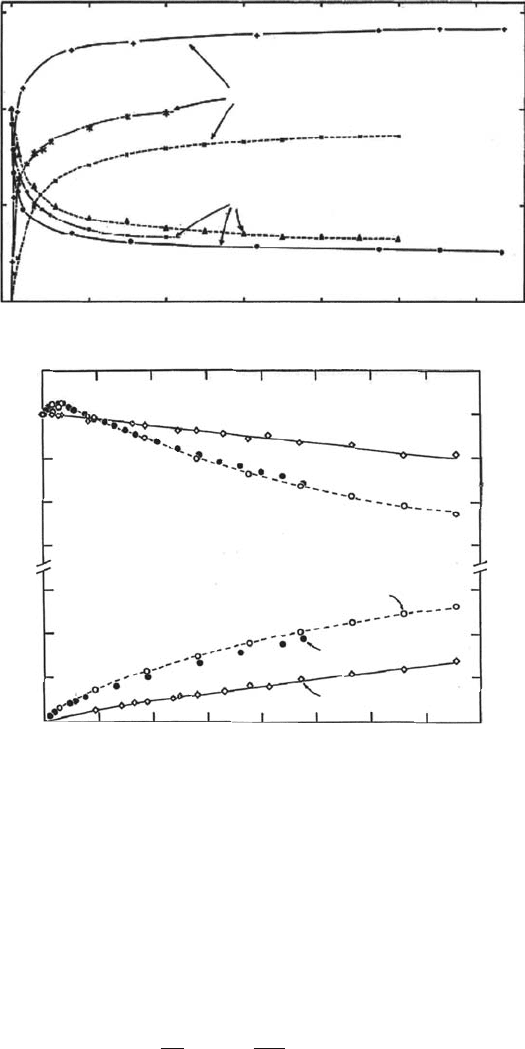

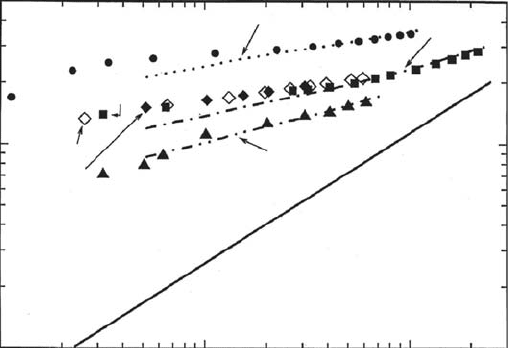

The drift velocities, v

d

, for electrons in LAr and LXe, shown in Figure 31.2, in the condensed phase,

are much higher than the corresponding values in the gas phase, normalized by E/N, because of the

formation of the conduction band. Here, E is the electric eld and N is the number density of atoms.

The electron mobilities in LAr, liquid krypton (LKr), and LXe are discussed elsewhere (Holroyd,

2004; Wojcik etal., 2004), and therefore, only briey mentioned here. Review articles for RGLs are

also found in Schwentner etal. (1985), Christophorou (1988), Holroyd and Schmidt (1989), and Lopes

and Chepel (2003). The properties of LAr and LXe as detector media are listed in Table 31.1.

The ion drift velocity is not so high as that for electrons, but ∼2–3 times larger than the value esti-

mated from the self-diffusion coefcient, D

self

(Hilt etal., 1994). The drift velocity is also observed to

be high in the solid (Le Comber etal., 1975). The positive charge carrier is not a free hole. The ion R

+

produced by the ionizing particles self-traps immediately to form

R

2

+

. The binding energy, E

b

, for

R

2

+

is only several tens of meV (Le Comber etal., 1975), which is quite small compared with correspond-

ing values of about 1eV in the gas phase (Mulliken, 1964; Kuo and Keto, 1983). The reduction in E

b

* Imaging Cosmic and Rare Underground Signals, http://icarus.lngs.infn.it/

†

Xenon MASSive detector for solar neutrino (pp/

7

Be), Xenon neutrino MASS detector (ββ decay), Xenon detector for

Weakly

Interacting MASSive Particles (DM search), http://www-sk.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/xmass/index-e.html

Applications of Rare Gas Liquids to Radiation Detectors 881

Energy (eV)

16

14

12

10

8

6

2

0

r

Ar+Ar

hν

I

I

Γ(1/2)

Γ(3/2)

Xe

C

2

H

4

C

3

H

4

TMA

TEA

3

2

1

E

g

n

Ar

2

*

Ar

2

+

Figure 31.1 Schematic diagram for condensed Ar. The inset is the emission spectrum of

Ar

2

*

. Ionization

potentials

in the gas phase (upper) and in LAr (lower) for various molecules are also shown.

LAr

10

2

10

6

10

5

10

4

10

3

10

–2

10

–3

3

Gaseous Xe

Gaseous Ar

LAr

LXe

LXe

3

E/P (V/cm

•

Torr)

Draft velocity (cm/s)

3

10

3

10

4

10

2

10

3

10

4

E (V/cm)

Figure 31.2 Electron drift velocity in liquid and gaseous Ar and Xe as a function of reduced electric eld

(Doke,

1981; Miller etal., 1968; Pack et al., 1962; Yoshino et al., 1976).

882 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

may be attributed to the formation of the conduction band. The small polaron (

R

2

+

, the carrier self-

trapped in its polarization eld) moves from one site to another by a tunneling or a hopping process.

The thermalization time, τ

th

, for the excess electron is quite large in RGLs, because of the lack

of an effective energy loss mechanism. τ

th

in LAr and LXe have been measured using the micro-

wave technique, and the reported values are 0.9 and 6.5 ns, respectively (Sowada et al., 1982).

Consequently, the thermalization length, l

th

, is also quite long compared with the Onsager radius

(the distance from the positive ion at which the Coulomb energy is equal to the thermal energy)

of about 40–110nm. The ions produced are no longer regarded as isolated even for the minimum

ionizing particles. The distributions of the electrons and ions are quite different following electron

thermalization. Also, the mobilities of the electron and of the positive charge are orders of magni-

tude different, as shown in Table 31.1. The basic recombination theories of Jaffe (1913), Onsager

(Onsager, 1938; Hung etal., 1991), and Kramers (1952) do not apply to the condensed rare gases.

The Mozumder model (Mozumder, 1995) deals with this problem; however, the direction of the

eld is restricted to be parallel to the electron track. The Thomas model (Thomas etal., 1988) con-

forms the charge yield fairly well with several parameters; however, the physical picture is not clear.

table 31.1

properties

of la

r

and lx

e

as d

etector

m

edia

lar lxe Comment

E

g

eV 14.3 9.28

W eV 23.6 15.6

W

ph

eV 19.5 14 rel. H.I.

N

ex

/N

i

0.21 0.06, 0.13

μ

e

cm

2

/V/s 475 1900 At T.P.

μ

h

10

−3

cm

2

/V/s 3.5 At T.P.

D

⊥

cm

2

/s

∼20 ∼80

At 1kV/cm

λ

nm 127 178

τ

S

ns 7 4.3

τ

T

ns 1600 22

τ

rec

ns 45 Apparent

τ

th

ns 0.9 6.5

l

ph

cm 66 29–50

T.P. K 84 161

D

self

cm

2

/s 2.43 × 10

−5

ρ

g/cm

3

1.40 2.94 At B.P.

n 1.54–1.70

ε

0

1.52 1.94

Radiation

length

a

cm 14 2.8 At 1 GeV

Moliere

radius

b

cm 10 5.7

Note: Doke (1981), Hitachi et al., (2005), Jortner (1965), Lopes and Chepel (2003),

Rabinovich

et al. (1988), Rahman (1964), Seidel (2002), Sinnock (1980).

a

Bremsstrahlung and electron pair production are the dominant processes for high-energy elec-

trons and photons. The radiation length, X

0

, is dened as the length that the high-energy

electron travels in matter losing its energy by bremsstrahlung to 1/e.A value for 1GeV is usu-

ally taken since the radiation length, X

0

, becomes almost independent of energy above 1GeV.

b

Moliere radius is given by the radiation length, X

0

, and the atomic number, Z, as

R X Z

M

= +0 0265 1 2

0

. ( . ).

R

M

is a good scaling constant of a material in describing the transverse dimension of elec-

tromagnetic

showers.

Applications of Rare Gas Liquids to Radiation Detectors 883

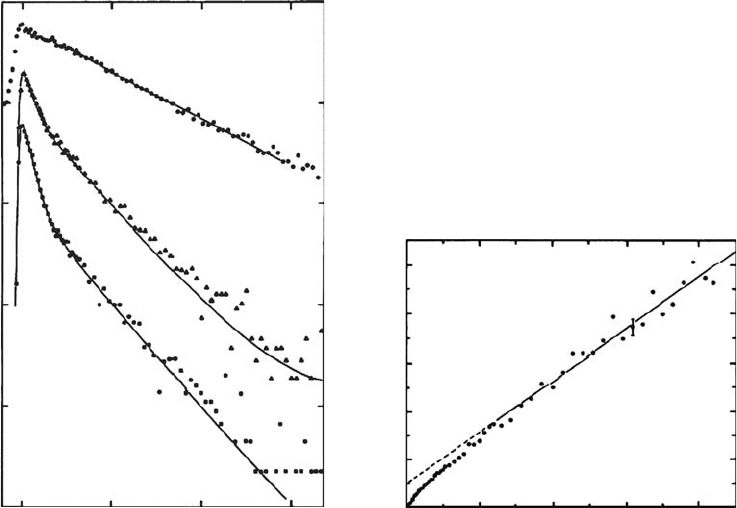

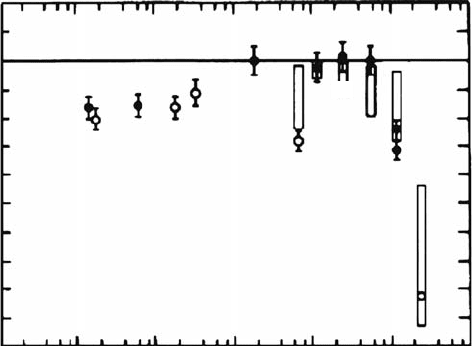

Both ionization and scintillation can be observed in RGLs. The ionization, Q, and scintillation,

S, yields observed for electrons, α-particles, and ssion fragments are shown in Figure 31.3, as a

function of the applied electric eld. The W-value, that is, the average energy required to produce

an ion pair, is smaller in the condensed phase than in the gas phase. The energy balance equation

(Platzman,

1961) expresses the W-value as

W

E

N

E

N

N

E= = +

+

0

i

i

ex

i

ex

ε (31.1)

where

E

0

is the energy of the ionizing particle

E

i

and E

ex

are the average energies expended for ionization and excitation, respectively, produc-

ing

N

i

ionizations and N

ex

excitations

ε

is the average energy spent as the kinetic energy of sub-excitation electrons

150

100

Q and L (arb. unit)

50

0

Q

Kr

L

Ar

Ar

Xe

Xe

Kr

0 2 4 6 8

Field strength (kV/cm)(a)

10 12

Ionization Q/Q

∞

or scintillation S/S

0

(b)

1.1

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.3

0.2

0.1

Electric field (kV/cm)

F.F. ×5

α 5.305 MeV

α 6.12 MeV

Ionization

Scintillation

LAr

F.F.

α

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Figure 31.3 (a) Ionization, Q, and scintillation, L, yields for electrons as a function of the applied electric

eld in LAr, LKr, and LXe. (From Kubota, S. et al., Phys. Rev. B., 20, 3486, 1979. With permission.) (b)

Ionization, Q, and scintillation, S, yields for α-particles and ssion fragments in LAr as a function of the

applied

electric eld (Hitachi etal., 1987).

884 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

The N

ex

/N

i

ratio in LAr is estimated to be 0.21 using the optical approximation and agrees well with

a measured value of 0.19 observed in the Penning ionization (Kubota etal., 1976). However, a value

of 0.06 estimated in LXe is much smaller than a value of 0.13 obtained from the variation of the

charge and scintillation relation with the applied eld. W-values measured are 23.6eV (Miyajima

etal., 1974) and 15.6eV (Takahashi etal., 1975) for LAr and LXe, respectively; these are smaller

than the corresponding values of 26.4 and 22.0eV, respectively, in the gas phase.

The molecular ion

R

2

+

recombines with a thermalized electron, producing

R

2

**

.

R

2

**

relaxes non-

radiatively to the lowest

R

2

*

(self-trapped exciton or dimer) levels via exciton levels. The ionizing

particles also produce excitons, R

*

and R

**

, and these again relax non-radiatively to

R

2

*

. The origin

of the vuv scintillation is almost the same as gas at high pressure, the transition from self-trapped

excitons (

1

Σ

u

+

and

3

Σ

u

+

) to the repulsive ground state,

1

Σ

g

+

, and gives a broad, structureless vuv band

(Jortner

etal., 1965), as shown in Figure 31.1.

R

2

R R

*

→ + + νh (31.2)

The self-trapping time of excitons is quite short, of the order of 1 ps (Martin, 1971). However, this is

long enough for the free excitons to play an important role in reactions such as the Penning ioniza-

tion (Kubota etal., 1976; Hitachi, 1984) and in high-excitation-density quenching (Hitachi etal.,

1992b). Thermal excitons can be very fast, since the exciton mass is only a few times the electron

mass. On the other hand, the energy transfers from

R

2

*

and

R

2

+

follow usual diffusion-controlled

mechanisms

(Hirschfelder etal., 1954; Yokota and Tanimoto, 1967; Hitachi, 1984).

The

scintillation decay shape in RGLs depends on the kind of ionizing radiation, as shown for

LXe in Figure 31.4. The electron excitation gives an apparent decay of 45ns (Hitachi etal., 1983).

10

4

10

3

10

2

10

1

0

Photon signal (arb. units)

50 100

Time (ns)(a)

Fission fragments

τ

S

= 4.1 ns

τ

T

= 21 ns

I

S

/I

T

= 1.52

Alpha

τ

S

= 4.2 ns

τ

T

= 22 ns

τ = 45 ns

Electron

LXe

I

S

/I

T

= 0.43

150

10

–1

(b) Time (μs)

electron

LXe

10

I

–1/2

(arb. units)

8

6

4

2

0

0 2 4 6 8

Figure 31.4 (a) Typical decay curves for the scintillation from LXe excited by electrons, α-particles, and

ssion fragments. (b) Variation of I

−1/2

, where I is the scintillation intensity, as a function of time due to elec-

tron

excitation for LXe (Hitachi etal., 1983).

Applications of Rare Gas Liquids to Radiation Detectors 885

It has a slow, non-exponential tail representing homogeneous recombination, as shown in Figure

31.4b. These components disappear under the electric eld and the decay shows two exponentials,

as those for α-particle and ssion fragment excitation; therefore, the slow decay has been attrib-

uted to recombination (Kubota etal., 1979, 1980). High-LET (linear energy transfer) particles,

α-particles and ssion fragments, show two decay components of 4 and 22ns, corresponding to

the singlet and triplet lifetimes, respectively. LAr shows basically only two exponential decay com-

ponents of 7ns and 1.6μs, representing the singlet and the triplet, respectively, due to electron,

α-particle, and ssion fragment excitation. In addition, the time prole also shows a rise time of

∼1ns and a few ns, respectively, for electron excitation in LAr and LXe, corresponding to the ther-

malization times (Hitachi etal., 1983). The decay shapes also show that the recombination in a

heavy ion track occurs faster than the thermalization in LAr and LXe. It should be mentioned that

the

purication of liquids is quite important for the decay time measurements.

The

singlet-to-triplet intensity ratio, S/T, depends on the LET. S/T plays an important role in

particle discrimination, as discussed in Section 31.4.3. In RGLs, it shows an opposite trend in LET

dependence as that for organic liquids. S/T increases with LET in RGLs. Strictly speaking, the LS

coupling (Russell–Saunders notation) is not adequate for heavy atoms such as Ar and Xe. Therefore,

the triplet states are not real metastables. The mechanisms proposed for S/T in organic liquids, such

as

spur recombination (Magee and Huang, 1972), do not apply to RGLs.

The

energy resolution, ΔE, for ionization particles of energy, E

0

, is given by

∆E FWE= 2 36

0

.

(31.3)

where F is the Fano factor, which can be smaller than 1 because the energy of the incident particle

is xed. The estimated F values become smaller in the condensed phase, because the existence of

the conduction band reduces the N

ex

/N

i

values considerably. The values of F estimated for LAr and

LXe are 0.12 and 0.06, respectively (Doke etal., 1976). However, such a good resolution has not

been reported so far. In fact, the measured resolutions are even worse than the values predicted by

the Poisson statistics. The best values obtained so far are 2–8 times those predicted by the Poisson

statistics. The reason for this is not understood as yet. The degradation of energy resolution in the

gas, as a function of density up to 1.7g/cm

3

, has been reported (Bolotnikov and Ramsey, 1997).

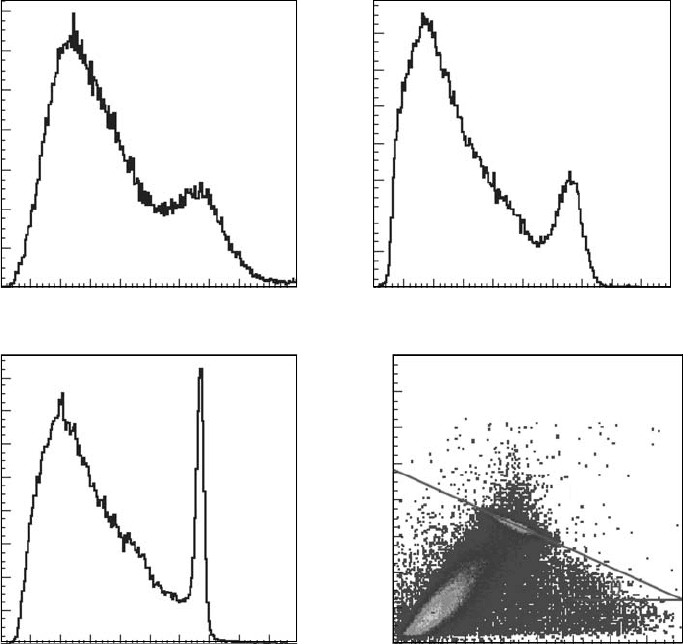

The ionization, Q, and scintillation, S, yields are complementary to each other, as shown in

Figure

31.3. We have (Masuda etal., 1989b)

Q aS

+ =

const. (31.4)

This is because there is no non-radiative relaxation path from the lowest molecular states,

R

2

*

, to

the ground state. An ionization or an excitation gives one free electron or one scintillation photon

in an RGL. The energy resolution obtained by the sum signal is much better than either of the two.

However, the number of photons produced is not easy to estimate because of the geometrical factor

and the quantum efciency of the photomultiplier (PMT). In addition, the electron escape prob-

ability, χ, for electron and γ excitations (Doke etal., 1985) and the quenching factor, q, for heavy

ions (Hitachi etal., 1987) are needed to determine a. The charge scintillation anti-correlation brings

about improvement in the resolution as a value reported of σ = 1.7% for 662keV γ rays at an electric

eld

as low as 1

kV/cm

in LXe, as shown in Figure 31.5 (Aprile etal., 2007).

A

good energy resolution can also be obtained by doping a trace of molecules in an RGL. The

method, that is, the photo-mediated ionization or the photoionization detection (Anderson, 1986;

Suzuki etal., 1986a,b; LaVerne etal., 1996), is particularly useful for heavy ions in which charge

collection is difcult. The idea is, instead of taking electrons from a strong cylindrical electric eld

of positive ions in the heavy ion track (Mozumder, 1999), to spread out the electron–ion pairs into

the entire detector volume and to isolate them from each other. The scintillation vuv photons pro-

duced in the ion track core carry the energy and transfer it to a doped molecule far from the track.

886 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

The charge collection increases drastically by the addition of a few ppm of photoionizing molecules.

The charge yield, Q

d

(E), for α-particles in doped LAr or LXe is given by that for pure liquid, Q

α

(E),

as

(Hitachi etal., 1997)

Q E Q E qN Q E Y E qN Y E

id iso ex iso

( ) ( ) [ ( )] ( ) ( )= +

′

− +

′

α α

η η (31.5)

with

the apparent photoionization yield, η′, expressed as

′

=η φ φg

vuv

(31.6)

where

g

is the fraction of vuv photons absorbed in the detector area

ϕ

vuv

is the quantum yield for vuv emission (∼1)

Y

iso

(E) is the fraction of collected charge expected for isolated ion pairs in pure liquid. Since no

value for isolated ion pairs is available, that for 1MeV electrons is substituted. Equation 31.5 con-

forms well with the experimental values except at a low electric eld, as shown in Figure 31.6.

1400

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

0

(a)

(c) (d)

(b)

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Energy from light (keV)

800 9001000

662 keV

662 keV

1400

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Energy from charge (keV)

800 9001000

1400

1600

662 keV

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Charge–light combined energy (keV)

800 9001000

662 keV

1400

1600

1200

1000

Energy from charge (keV)

800

600

400

200

0

0 200 400 600

Energy from light (keV)

800 1000 1200 1400 1600

Figure 31.5 The energy resolution obtained by ionization (a), scintillation (b), the sum signal (c), and a

scatter

plot (d) in LXe at an applied eld of 1

kV/cm

(Aprile etal., 2007). (Courtesy of XENON.)

Applications of Rare Gas Liquids to Radiation Detectors 887

A large increase in charge collection can be obtained even at an electric eld as low as 1–2kV/cm.

Agood energy resolution of 1.4% FWHM (full width at half maximum) is reported for α-particles

in 4ppm of allene-doped LAr (Masuda etal., 1989a). The best resolution reported is 0.37% FWHM

for 33.5MeV/n O ions in 80ppm of allene-doped LAr (Hitachi etal., 1994). However, these resolu-

tions

are still 3–8 times worse than the values predicted by the Poisson statistics.

The

photoionization quantum yield, ϕ, for doped molecules is quite large in LAr and LXe

(Hitachi

etal., 1997) than that in the gas phase at the same excess energy, E

Δ

:

E h I

g

l

∆

= −v (31.7)

where,

I

g

l

is the ionization energy in the RGL. In fact, the values obtained for trimethylamine (TMA)

and triethylamine (TEA) are 0.8 in LXe in spite of the excess energy being only ∼1eV. One reason

may be attributed to the cage effect (Hynes, 1985; Schriever etal. 1989). The ϕ values of TMAE

(tetrakis-dimethylaminoethylene) in supercritical LXe are also reported to be large compared with

the values in gas (Nakagawa etal., 1993). Few measurements are reported for ϕ in organic liquids

because of experimental difculties (Koizumi, 1994). More studies are needed for the photoioniza-

tion

of molecules in liquids.

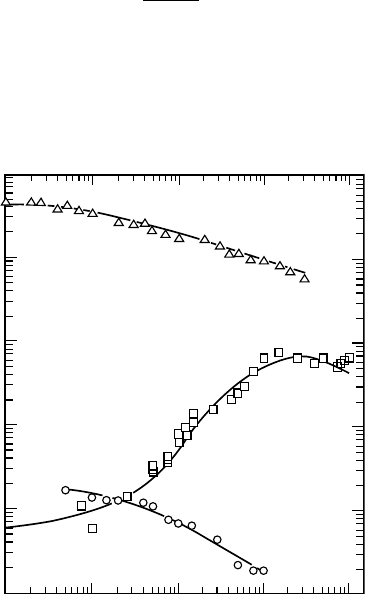

The

scintillation yield, that is, the scintillation per unit energy deposit, in LAr is shown as a func-

tion of LET in Figure 31.7. The scintillation yields obtained for relativistic heavy ions (∼GeV/n), Ne,

Fe, Kr, and La are the same and do not show quenching (i.e., quenching factor q = 1). RGLs are the

strongest scintillators against high-excitation-density quenching among scintillators in solid and liq-

uid phases. The scintillation yields for α-particles, ssion fragments, and relativistic Au are smaller

because of quenching. Similar results have been obtained for LXe (Tanaka etal., 2001). The scintilla-

tion yield for electrons and H ions are also smaller not because of quenching but because of insufcient

recombination (escaping electrons). The thermalization length in RGLs is large, and some electrons do

not recombine within the usual observation time or go to the wall. The sum signals for these low-LET

particles become the same as those for the relativistic heavy ions with no quenching.

The Birks model of scintillation quenching (Birks, 1964) does not apply to RGLs. A biexcitonic col-

lision model has been proposed. The lifetimes of the singlet and triplet states do not depend on LET;

therefore, excimer states,

R

2

*

, are not responsible for quenching. The “free” exciton plays an important

50

Allene (25 ppm)

TMA(3 ppm)

Ethylene

(155 ppm)

(200 ppm)

10

0.1 1 10

Electric field (kV/cm)

Collected charge (%)

TEA (200 ppm)

Pure liq. Ar

η΄= 0.32/2

η

΄

= 0.60/2

η

΄

= 0.22/2

30

1

Figure 31.6 Collected charge, Q/N

i

, where N

i

is the total ionization (in unit of electrons) for α-particles as

a function of the applied electric eld in LAr and doped LAr (Hitachi etal., 1997). Curves give the calculated

results

from Equation 31.5.

888 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

role. The quenching mechanism that consists of exciton–exciton collisions and diffusion is discussed

elsewhere (Hitachi etal., 1992b). The proposed quenching mechanism is biexcitonic collision:

R R R R e K E

*

*

. .+ → + +

+ −

( )

(31.8)

where R

*

is the free exciton. The ejected electron, e

−

, will lose the kinetic energy close to the ioniza-

tion energy before it recombines with an ion, again to produce excitation. The overall effect is that

two

excitons are required for one photon.

The

total energy, T, given to the liquid by a heavy ion is divided into the core, T

c

, and the pen-

umbra, T

p

(Mozumder etal., 1968; Mozumder, 1999). The quenching model assumes that quench-

ing takes place exclusively in the high-excitation-density track core. The energy, T

s

, available for

scintillation

is

T qT q T T

s c c p

= = + (31.9)

where q and q

c

are the overall quenching factor and the quenching factor in the core, respectively.

The quenching factors are dened as 1 for no quenching and 0 for total quenching. Typically, T

c

/T

values are 0.5 and 0.7 for relativistic heavy ions and α-particles, respectively. The hard-sphere col-

lision and a dipole–dipole mechanism (Watanabe and Katuura, 1967) were considered for the cross

sections, σ, for process in Equation 31.8. The rate constant, k, is given by k = σv, where v is the

thermal velocity of collision partners (v ∼ 1.2 × 10

7

cm/s). Diffusion reaction equations were solved

by the method of prescribed diffusion. The results calculated for are compared with experimental

results

in Figure 31.7.

An

increase in scintillation has been reported in LAr with the application of an electric eld of a

few kV/cm (Hitachi etal., 1987, 1992a, 2002; LaVerne etal., 1996). The increase occurs at a eld much

lower than that required for proportional scintillation (10

6

V/cm), and it is attributed to the recovery of

quenching in the high-excitation-density region of the heavy ion track. The applied electric eld may

shift the distributions of negative and positive charges, thereby consequently reducing the excitation

density, as a result, quenching.

1.2

1.0

0.8

H

He

[H]

[α]

Au

La

Fe

Ne

(FF)

e

–

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0.1 1

LET (MeV g

1

/cm

2

)

dL/dE

10

10

2

10

3

10

4

10

5

Kr

Figure 31.7 The scintillation yields for various particles in LAr as a function of LET. Circles show experi-

mental results (Doke etal., 1988). Closed circles are for relativistic ions. Vertical boxes show a diffusion reac-

tion model based on biexcitonic quenching (upper end: a dipole–dipole collision cross section, lower end: the

hard-sphere

collision cross section divided by 4 (Hitachi etal., 1992b).

Applications of Rare Gas Liquids to Radiation Detectors 889

The attenuation lengths, the length at which the number of photons or electrons reduces to 1/e,

for photons (l

ph

) and electrons (l

e

) are important factors for large-scale detectors. An l

e

value of

more than 1m (Masuda etal., 1981), which corresponds to a free-electron lifetime of ∼ ms, has been

obtained. However, l

ph

reported for LAr and LXe are only 66 and 30–50cm, respectively (Ishida

etal.,

1997). Rayleigh scattering seems to limit l

ph

(Seidel etal., 2002).

When an RGL is used as an ionization detector, it is important to remove the electron-attaching

compounds, such as oxygen and uorinated or chlorinated compounds. The electron attachment to

an

impurity, M, can be described by the following reaction:

e

M

− −

+ ⇒M M

k

(31.10)

where k

M

is the rate constant. The number of electrons, N

e0

, produced by the passage of an ionizing

particle

at time t = 0 is reduced to N

e

after time t:

N N

t

e e

e

e

=

−

0

/τ

(31.11)

where τ

e

is the electron lifetime and is related to the rate constant and the impurity concentra-

tion, [M], by

τ

e

M

=

1

k M[ ]

(31.12)

The rate constant is a function of the applied electric eld, as is shown in Figure 31.8 for O

2

, N

2

O,

and SF

6

(Bakale etal., 1976). The attenuation length, l

att

, is related to the lifetime by the electron

drift

velocity, v

d

:

10

15

10

14

10

13

10

12

10

11

10

10

10

10

2

10

3

10

4

10

5

SF

6

N

2

O

O

2

Electric field strength (V/cm)

k (e

–

+S) (1/M

/

s)

Figure 31.8 The electron attachment rate constant, k

M

, as a function of the electric eld for O

2

, N

2

O, and

SF

6

(Bakale etal., 1976).