Hatano Y., Katsumura Y., Mozumder A. (Eds.) Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter - Recent Advances, Applications, and Interfaces

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

210 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

9.1 introduCtion

In the interaction of charged particles and photons with matter, electrons occupy a central position,

both as an incident radiation and as a chemical reactant. Of particular interest are electrons liber-

ated from geminate cations, which may be free, quasi-free, or trapped. Such electrons are extremely

important for consideration, inter alia, of radiation-induced conductivity and dosimetry. Since some

energy states of the electron must be delocalized to confer upon it a nonzero mobility (long-range

transport), electron localization and trapping have emerged as important topics of investigation

(Anderson,

1958; Hug and Mozumder, 2008).

In

this chapter, our aim is to provide a consistent theoretical framework for electron localization

and trapping in hydrocarbon liquids. Saturated hydrocarbon molecules do not have positive electron

afnities. Yet, in the liquid phase, electron trapping is ubiquitous, as evidenced from the activated

mobility in these liquids (Allen, 1976; Nishikawa, 1991). So far, most of the theoretical treatments

have been phenomenological, in that a certain two-state model is assumed and its parameters are

adjusted to reproduce the correct order of magnitude of the room temperature mobility and its activa-

tion energy. In these models, electron motion is assumed to be divided between those in the quasi-free

and trapped states, in direct proportion to the respective mobilities in these states (Davis and Brown,

1975; Allen, 1976; Nishikawa, 1991). The activation energy is similar to, if not identical with, the bind-

ing energy in the trap. The magnitude of the mobility is then given through the quasi-free mobility for

which often a uniform value of ∼100cm

2

V

−1

s

−1

is assigned. Mozumder (1993, 1995) introduced an

essential improvement of the model by explicitly recognizing the competition between trapping and

momentum relaxation processes in the quasi-free state. Yet, the most important question remained

unanswered, that is, what characteristics of the individual molecule and/or of the liquid structure are

responsible for initial localization and, subsequently, for trapping. Sometimes, the Anderson model

has been invoked, but no calculation has been provided to indicate the physical parameters respon-

sible for localization (Funabashi, 1974; Cohen, 1977; Chandler and Leung, 1994). Recently, however,

Hug

and Mozumder (2008) have employed the Anderson theory with the anisotropy of the electron–

molecule

polarizability interaction as the source of diagonal energy uctuation and with the liquid

x-ray structure to provide the connectivity. Thus, they were able to evaluate approximately the fraction

of the initial electron states that would be delocalized in the liquid alkane series. Further work is in

progress along these lines (Hug and Mozumder, forthcoming).

The relationship between electron mobility and molecular shape, especially for the isomeric pen-

tane series, has often been alluded to, but without any specic conclusion; in the same manner, certain

intramolecular properties have been addressed, again without proven specics (Hug and Mozumder,

2008). Our assertion is that both intra- and intermolecular factors are responsible for electron localiza-

tion and trapping, for example, the electron–molecule anisotropic polarizability interaction and the

liquid structure factor. We will develop these ideas in this chapter for localization, which is considered

rst. Some models of trapping and their consequences would then be provided.

In Section 9.2, the Anderson model of localization of electrons is discussed, with special refer-

ence to liquid alkanes. Section 9.3 is devoted to trapping, following initial localization. In Section 9.4,

mobility theories are briey considered. We summarize our conclusions in Section 9.5.

9.2 loCalization

9.2.1 localization and trapping

A distinction should be made between localization and trapping. Localization, at least in the sense of

Mott (1967) and Anderson (1958), implies that the overall envelope of the wave functions for an elec-

tron is conned within a microscopic volume of the space without rearrangement of the medium mol-

ecules. Trapping requires medium rearrangement, with a concomitant abrupt change in the energy and

position of the electron (Cohen, 1977). According to Cohen (1973, 1977), the free energy is irreversibly

Electron Localization and Trapping in Hydrocarbon Liquids 211

lowered on trapping. The self-trapped conguration is locally stable, and a mixture of quasi-free and

trapped states can occur, with little probability of intermediate states. No stable self-trapped state

may be found within the deformation potential approximation. Along with self-trapped states, there

is always a possibility of preexisting traps, created by random equilibrium uctuation in the density

and/or potential in the liquid. Unfortunately, in the literature, the distinction between localization and

trapping is not always carefully maintained, and the terms are used interchangeably.

9.2.2 diSorder: the anderSon Model

Localization in a condensed phase is intimately connected with disorder, which does not mean lack of

all order. It implies absence of translational symmetry, which destroys long-range order. There is always

a short-range order dictated by intermolecular chemical bonding. Although many of the crystal proper-

ties are lost in disordered systems (e.g., the Bloch states), two of them remain (Ziman, 1979). The rst is

homogeneity. Thus, a translation from a molecule at r⃗

i

to another at r⃗

j

may be associated with a phase fac-

tor, exp[ik

⃗

· (r⃗

i

− r⃗

j

)], which is the closest analogue to Bloch waves for homogeneously disordered systems.

However, it does not hold for k compared to the reciprocal of average intermolecular spacing. The second

is that almost all disordered liquids are relatively close-packed, subject to the constraints of chemical

bonding and local structure, implying that the Wigner–Seitz cell must be replaced by Voronoi polyhe-

dra, both of which are space-lling. Further, Ioffe and Regel point out that in cases where the coordina-

tion number is preserved upon melting, the liquid roughly inherits the band structure of the solid.

Two important properties of the medium are the coordination number, Z, and the connectivity, K.

The coordination number is the unique number of nearest neighbors in an atomic solid. The maxi-

mum value of Z, that is, Z = 12, is found in face-centered cubic (fcc) crystals (many metals) and also

in liqueed rare gases (LRGs) and solid methane. In molecular media, Z may be dened by a small

set specifying nearest-neighbor environments for each distinct site type. In practice, Z is obtained by

integrating the molecular pair distribution function, g(r), which in turn is based on the small-angle

x-ray

scattering data (Hug and Mozumder, 2008), as given below:

Z r g r dr

r

r

=

∫

4

2

π

min

max

( ) . (9.1)

In Equation 9.1, r

min

is automatically obtained from x-ray data by the elimination of intramolecular

scattering.

About r

max

, there is some choice depending on the method employed.

We have consistently used a criterion by which g(r) returns to 1 for the rst time beyond the

principal

peak (Hug and Mozumder, 2008).

The

connectivity, K, determines how well the elements of the lattice (not necessarily crystalline)

are connected together. If the lattice has only nearest-neighbor connections, K may be dened by

K= L

−1

ln[N(L)], where N(L) is the number of non-repeating paths of length L emanating from a site.

Classically, for a regular lattice, it is Z − 1 or Z − 2, depending on the circumstances (Anderson,

1958). For a Bethe–Peierls lattice (see Section 9.2.4, Figure 9.2), N(L) = (K + 1)K

L−1

. To verify

this, consider N(1) = K + 1 and N(L + 1)/N(L) = K(L ≥ 1), both of which are obvious; then iterate.

Aquantum analogue is also available, but seldom used except in model numerical studies (Root

etal., 1988). For liquid hydrocarbons, we have consistently used K = Z − 1 (Hug and Mozumder,

2008). It is then clear that the coordination number enters the localizability criterion in two ways.

First, it determines the random site energy uctuation, due to each electron–molecule interaction.

Second, it spreads the electron wave function from one molecule to the next. The increase of Z tends

to localize the electron by the rst effect, and then tends to delocalize it by the second effect. In a

given

situation, the extent of localization is a result of the competition between these two effects.

Originally,

the Anderson model (1958) was devised to explain the lack of spin diffusion in low-

temperature pure Si with donor impurities (P, As, etc.). Experiments indicated spin localization in

212 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

the timescale of seconds or longer (Feher etal., 1955), by which time the spin should have com-

pletely diffused out by ordinary transport theory. Anderson argued that spin energy at a given loca-

tion (called the site energy) is subject to random uctuation due to the hyperne interaction. This

generates what has since been known as diagonal disorder. When the site energy uctuation has a

narrow width of distribution, W, relative to the bandwidth, B, caused by transfer from one location to

the next (W ≪ B), transport is easy, because of the facility of nding energy-matched states. Onthe

other hand, when W >> B, a state picked at random will have energy that has little chance to match

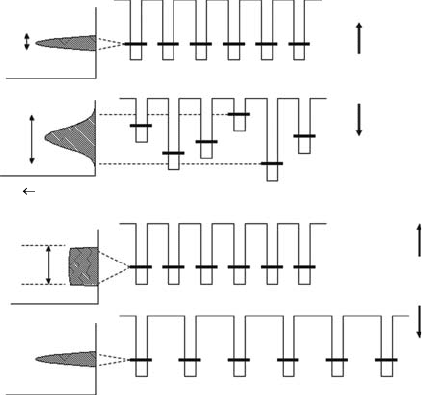

at the transferred location. The sites are then effectively decoupled, and the transport stops. Figure

9.1

gives a qualitative description of this phenomenon.

Soon

after Anderson’s pioneering work, it was realized that, in a random lattice, the transport of

other species, for example, electrons and excitations, can be described in the same way by constructing

a suitable physical model for diagonal disorder and for transfer energy. It turns out that the statistical dis-

tribution of site energy is the most important thing. The transfer energy may have some uctuation, but

it is not too relevant. Actually, in most tight-binding approximations (TBAs), it is treated as a constant.

We now state Anderson’s theorem in a qualitative form. For a sufciently large disorder (W/B

>> 1), all states in the band are localized and no transport at all can take place. Later, we derive a

quantitative criterion. A-localization, for brevity, is purely a quantum mechanical consequence of

disorder in an independent particle picture. It is important to realize that A-localization describes

lack of quantum diffusion, not that of thermal diffusion. Stated in this manner, it is exactly valid

at the absolute zero of temperature. At a nite temperature, a small transport is always allowed by

thermal activation. Mott (1967) adds that, even at smaller disorders, some states in the band tail are

localized. Another kind of localization, often invoked in alloys, is due to an electron–electron cor-

relation energy uctuation (U). This phenomenon, called a Mott transition, occurs when U > B in a

necessarily

two-electron picture.

9.2.3 relevance to hydrocarbon liQuidS

In liquid alkanes, electron trapping is ubiquitous, with the exception of liquid methane. Clear evidence

of it comes from the activation energy of mobility, for which values of the order of several times

(a)

B

B

W

n(E)

B >W

B<W

B>U

B<U

Anderson

transition

Mott

transition

(b)

Figure 9.1 Schematic contrast of the (a) Anderson and (b) Mott transitions. B is the electronic bandwidth,

U is the intersite electron–electron energy, W is the width of the disorder in the site energies in the one-

electron

tight-binding picture of Anderson.

Electron Localization and Trapping in Hydrocarbon Liquids 213

the thermal energy, k

B

T, have often been found experimentally (Allen, 1976; Nishikawa, 1991). Since

localization is a prerequisite for trapping, it becomes an established fact.

The theoretical description of electron localization and trapping in liquid hydrocarbons has been

so far largely phenomenological (Dodelet and Freeman, 1972, 1977; Davis etal., 1973; Dodelet

etal., 1976; Holroyd, 1977; Mozumder, 1993, 1995). In the often-used two-state models, electron

mobility is seen as a combination of mobilities in the trapped and quasi-free states, in direct proportion

to the lifetimes in these states. Given a trap density, a binding energy in the trap, and the mobility

of the electron in the quasi-free state, one can calculate the effective mobility of the electron and its

activation energy, which compare well with experiments for reasonable values of the parameters.

Certain other features, such as solute reaction rates with the electron and the eld dependence of the

mobility, can also be explained within the context of these models.

Despite the apparent success of the two-state models, the basic problem remained unanswered, that

is, what properties of the molecule and of the liquid structure give rise to electron localization or delo-

calization. Sometimes the Anderson localization has been cited as a possible mechanism (Cohen, 1973;

Funabashi, 1974; Chandler and Leung, 1994), but no calculations or realistic models have been proposed

so far. Only recently, Hug and Mozumder (2008) have employed the anisotropy of the electron–molecule

polarizability interaction as the explicit cause of diagonal disorder in these systems. Although some

progress has been made in this manner for the localization problem, many details remain to be lled

in, especially those concerned with the relationship of transfer energy to V

0

, the lowest energy of the

conducting state in the liquid. Finally, the problem of trapping ensuing upon localization has not been

adequately addressed. We consider these problems in some detail in this chapter.

A well-known, but little understood, problem relates to molecular shape dependence of mobil-

ity. Generally speaking, liquids of nearly spherical molecules have electron mobility (μ

e

) much

larger than in those where the molecules are less spherical (Schmidt and Allen, 1970; Dodelet

and Freeman, 1972, 1977; Bakale and Schmidt, 1973; Allen, 1976; Holroyd and Cipollini, 1978).

Aspectacular contrast among isomeric pentanes has often been alluded to and discussed (Freeman,

1986; Stephens, 1986; and references therein). Electron mobility in neopentane is ∼60 times that

in isopentane and ∼400 times as great as in n-pentane. In many other respects, the molecules

are very similar. A corresponding situation exists for tetramethylsilane (TMS) and its variants,

tetramethylgermanium (TMGe), and tetramethyltin (TMSn) (Holroyd et al., 1991). Various cor-

relations, but no real explanation, have been proposed between μ

e

and some intramolecular proper-

ties, for example, polarizability anisotropy (Dodelet and Freeman, 1972, 1977; Funabashi, 1974;

Gyorgy and Freeman, 1979), molecular symmetry (Shinsaka etal., 1975), and sphericity (Dodelet

and Freeman, 1972, 1977). Stephens (1986), and references therein, argued against the intramolecu-

lar correlation by pointing out that the density-normalized mobility curves for isomeric pentanes

reverse their order in the gas phase, while crossing over near the critical density. He stressed the

relevance of the peak position of the liquid scattering function, S(k), determined by x-ray measure-

ment. Freeman (1986), and references therein, was generally supportive of this idea, but criticized

the direct correlation, because the peaks in S(k) for n-, iso-, and neopentane did not follow the

sequence of μ

e

. He also pointed out that the details relied in part on the differences in the struc-

ture functions that were likely to be the same within experimental uncertainty, especially between

iso- and neopentane. The central idea of this chapter is that the entire liquid structure needs to be

considered

for localization, and both intra- and intermolecular properties are involved.

9.2.4 baSic derivationS

Anderson’s model of localization is of general validity for any inherent species, electrons, spin, and

excitation states, even though in the present case we are dealing with electrons (Anderson, 1958). Site

energy, ε

n

, is a random variable characterized by a distribution function, p(ε

n

). The matrix elements,

V

nm

, negotiating transfer between nearest neighbors only, are taken to be a constant V. This is a tight-

binding model for noninteracting electrons. Anderson shows that if the variation in ε

n

is large enough

214 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

compared to V, then an electron on a particular site will not be able to easily hop to its nearest neighbor,

because energy cannot be conserved in the absence of a heat bath. This implies localization.

The theory can be developed in several different ways. The question of localization can be

reduced to whether there is any chance that an electron starting out at time t = 0 on site n will remain

there at time t → ∞. To this end, Anderson (1958) starts with the time-dependent Schrödinger equa-

tion for the Hamiltonian H = H

0

+ V, where the unperturbed Hamiltonian, H

0

, already contains the

statistically distributed energy, ε

n

. The Laplace-transformed state amplitude is then developed as

a perturbation series in V. While Anderson insists that the entire perturbed series be treated as a

probability

variable, its convergence is identied with localization without a direct correspondence

between

perturbed and unperturbed states.

In

Anderson’s treatment, repeated indices are allowed in the perturbation series, which is compu-

tationally inconvenient. To avoid this, he employs Watson’s method (Watson, 1957), which replaces

site energies by “renormalized energies,” to be determined self-consistently. Graphically, this pro-

cedure is equivalent to a “self-avoiding random walk” problem. Following a fairly complicated

mathematical reasoning, Anderson concludes that the perturbation series almost always converges,

that is, localization occurs, if W/V is greater than a critical value, where W is the “width” of the

statistical distribution of site energies. Two criteria have been derived, one for an upper limit and the

other

for the best estimate, both depending on the lattice connectivity.

Abou-Chacra

etal. (1973) point out several aws in Anderson’s original treatment, of which two are

important:

(1) approximation of the renormalized perturbation series with complicated denominators

may be inadequate and (2) while the terms of the series may be written as sums of contributions with

probability distributions, these contributions are not wholly independent. Instead of correcting these

aws, they provide a somewhat different procedure, still within the context of the Anderson model.

Their method is based on a self-consistent solution for the equation of self-energy in second-order

perturbation (vide infra). This solution can be purely real almost everywhere (localized states), or can

be complex everywhere (delocalized states). The present method replaces the difculty of nding the

convergence of Anderson’s series of high-order perturbation by a self-consistent procedure on the self-

energy, which is a distinct advantage. However, it applies essentially to an innite Cayley tree (Bethe

lattice), for which their theory is exact and a useful approximation for a real lattice in the case of the

Ising (1925) model. In principle, Anderson’s method should apply to any lattice. Localized states are

those in which the imaginary part of self-energy → 0, with probability unity as E → real axis. For

delocalized states, the imaginary part of self-energy remains nite and nonzero as E → real axis.

In the Anderson model, there is only one energy level, ε

i

, statistically distributed at site i (diagonal

disorder), while the electron is transferred from i to j by the matrix element (overlap integral) −V

ij

(often taken as a constant V for nearest neighbors). Schrödinger’s equation for the eigenstate α is

characterized by an amplitude

a

i

α

and an eigenvalue E

α

, which satisfy

ε

α α α α

i i ij

j

j i

a V a E a− =

∑

.

Matrix elements of Green’s function, dened operationally by G = (E − H)

−1

, are given by

( )

( )E G V G E

i ik ij jk

j

ik

− =

∑

ε δ , while, by denition, self-energy is written as follows:

S E E G E

i i ii

( ) [ ( )] .= − −

−

ε

1

Note that self-energy is site-specic at this level and connects with only the diagonal matrix ele-

ments of G. Self-energy is a renormalized energy including the interactions. In Anderson’s original

method (Anderson, 1958), the self-energy is expanded as a perturbation series, each term of which

contains a modied self-energy up to a certain approximation, corresponding to self-avoiding paths.

It is a complicated expression even for the relatively simple model of Anderson, as shown in the

following equation:

Electron Localization and Trapping in Hydrocarbon Liquids 215

S E

V V

E S E

V V V

E S E E

n

nj jn

j j

n

j n

nk kj jn

k

k

nj

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

=

− −

−

− −

( )

−

≠

∑

ε

ε ε

jj j

n

k n jj n

S E−

( )

+

≠≠

∑∑

( )

,

( )

In this equation, the V

nn

term is dropped. The S’s in the denominator are self-energies of the sites

specied in the subscript with specic sites named in the superscript not being considered. Then the

convergence and the statistical properties of the sum are investigated. In the present method (called

AAT), only the rst term of the series, corresponding to second-order perturbation, is retained,

however, insisting that self-energy distribution must be the same on both sides of the equation. This

gives the fundamental equation:

S E V E S E V

i ij

j

j j ji

( ) [ ( )] .= − −

∑

−

ε

1

(9.2)

Taking V

ij

= V, a constant for nearest neighbors, and noting that ε

i

are random and independent, it is

argued that S

i

(E) would be a random variable independent of ε

i

and that the probability distribution

of

S

i

(E) and S

j

(E) would be identical.

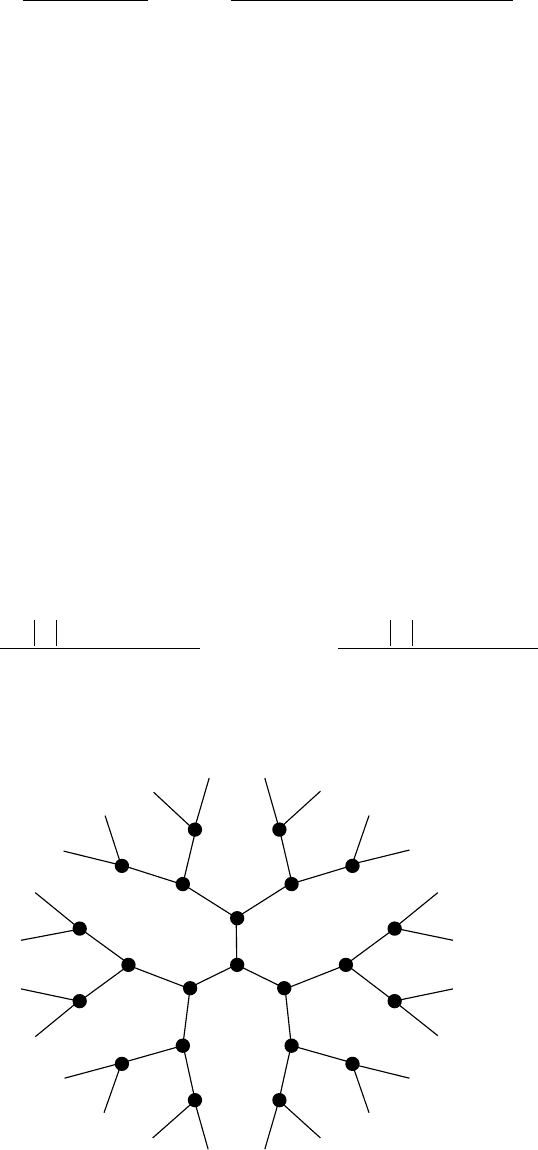

A Cayley-tree (Bethe lattice, see Figure 9.2) is characterized by a connectivity K = Z − 1, where

Z = coordination number of nearest neighbors. The number of nonintersecting paths emanating

from a given site is (K + 1)K

L−1

, where L is the step size. For nearest-neighbor interactions only,

the perturbation series reduces to a single term, thus offering simplication over a regular lattice.

Nonintersecting paths starting and ending in i have only two steps, i → j → i. Thus, the above

equation for self-energy has K terms on the right-hand side. There are K independent random

variables, S

j

(E), and K independent random energies, ε

j

, giving 2K independent random variables.

These generate a distribution of S

i

(E), identical to that of S

j

(E), in a self-consistent fashion.

AAT rst separate the real and imaginary parts of E = R + iη and S

i

= E

i

− iΔ

i

, and obtain from

Equation

9.2,

E

V R E

R E

V

R

i

ij j j

j j j

j

i

ij j

j

=

− −

− − + +

=

+

− −

∑

2

2 2

2

( )

( ) ( )

( )

(

ε

ε η

η

ε∆

∆

∆

and

EE

j j

j

) ( )

.

2 2

+ +

∑

η ∆

(9.3)

Taking p(ε

j

) as the site energy probability and calling f(E

j

,Δ

j

) as the joint probability of (E

j

,Δ

j

), AAT

derive a nonlinear integral equation for the (double) Fourier transform of f, which is very difcult to

Figure 9.2 Bethe lattice with Z = 3.

216 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

solve. Considerable simplication is achieved when η is very small (the important case), and Δ

j

s are

very

small (the localized case). In this approximation, one gets from (9.3)

E

V

R E

V

i

ij

j j

j

i

ij j

=

− −

=

+

∑

2 2

( )

( )

(

ε

which does not involve and∆ ∆

∆

ηη

ε

)

( )

.

R E

j j

j

− −

∑

2

(9.4)

The inhomogeneous equations (9.4) have a solution if the homogeneous equations,

λ ε

2

2

2

∆

i ij j j

j

V R E= − −

(

)

∑

( ) , have the largest eigenvalue λ

−2

< 1. λ = 1 separates the stabil-

ity of localized states. To determine the upper limit of the width of site energy distribution for

localized states, AAT ignore the real part of self-energy, as in Anderson (1958), thus obtaining

∆ ∆

i ij j j

j

V R= + −

∑

2

2

( ) /( )η ε (cf. Equation 9.4). The corresponding Laplace transform of its

probability

is given by

f s dx p R x f

sV

x

sV

x

K

( ) ( ) exp .= −

−

∫

2

2

2

2

η

(9.5)

The Laplace transform is more convenient for studying long time behavior (s → 0). A criti-

cal value of V (or of W/V) can be obtained from Lim

s→0

f(s). The probability of Δ

i

falls off as

|Δ

i

|

−3/2

, if p(R) ≠ 0. The tails of the distribution can fall off no faster than this. Thus, assuming

Lim

s→0

f(s) ≈ 1 − As

β

, with 0 < β < 1/2, and substituting in Equation 9.5, one obtains

KV

dx p R x

x

2

2

1

β

β

( )

.

−

=

∫

(9.6)

Differentiating Equation 9.6 with respect to β for given energy R and site energy distribution p(ε),

one

obtains a critical value of V as follows:

ln

( ) ln

( )

,V

p R x x x dx

p R x x dx

c

c

c

=

−

−

−

−

∫

∫

2

2

β

β

(9.7)

where V

c

and β

c

also satisfy Equation 9.6. Taking R = 0 at the band center and uniform site energy

distribution between –W/2 and +W/2 (Anderson model), AAT obtain, from Equations 9.6 and 9.7,

lnV

c

= ln(W/2) − (1 − 2β

c

)

−1

and (2V/W)

2β

K/(1 − 2β) = 1, which on eliminating β give the upper limit

equation

of Anderson (1958):

W

V

fK

W

V

c c

2 2

=

ln ,

(9.8)

with f = e, the base of natural logarithms. Anderson’s best estimate, with f = 2 in Equation 9.8, can also

be obtained similarly when R << W/2. We have consistently used a form of Equation 9.8 (vide infra).

The theory of Abou-Chacra etal. (1973) is regarded exact for an innite Cayley tree, or a good

approximation for a real lattice at the level of mean eld. It is supposed to be free of approximations,

but

not free from assumptions.

9.2.5 Mobility edge: Scaling theory reSultS

The term “mobility edge” was coined by Cohen, Fritzsche, and Ovshinsky (Cohen et al., 1969).

From the previous discussion, it is clear that the central idea in electron localization in a condensed

Electron Localization and Trapping in Hydrocarbon Liquids 217

medium is the interplay between the diagonal disorder (W), the transfer integral (V), and the

connectivity (K) (cf. Equation 9.8). As stated in Section 9.2.4, the numerical factor f depends, inter

alia, on the nature of the random lattice. For Anderson’s (1958) uniform site energy distribution

between –W/2 and +W/2, the f-values have been substantiated by the more accurate self-consistent

solution of the equation of self-energy by Abou-Chacra etal. (1973). According to Phillips (1993),

fshould equal 4 on a Cayley tree, which is completely unacceptable for liquid hydrocarbons (Hug and

Mozumder,

2008). If we take f = 4 in Equation 9.8, (W/2V)

c

would be so large that almost all states

would be delocalized. While the connectivity K is predominantly a medium property, Shante and

Kirkpatrick (1971) have determined numerically K = 4.7 for percolation on a cubic lattice. For the

same lattice, Chang etal. (1990) found (W/2V)

c

= 6.0 by a scaling calculation. (Simply stated, such a

powerful numerical technique relies on scaling the Hamiltonian and the consequent wave functions

by factors that can be used repeatedly to determine if or not the position probability distribution

remains localized in the long time limit.) Substituting the results of Shante and Kirkpatrick (1971)

and of Chang etal. (1990) in Equation 9.8, Hug and Mozumder (2008) obtained f = 0.7125, which

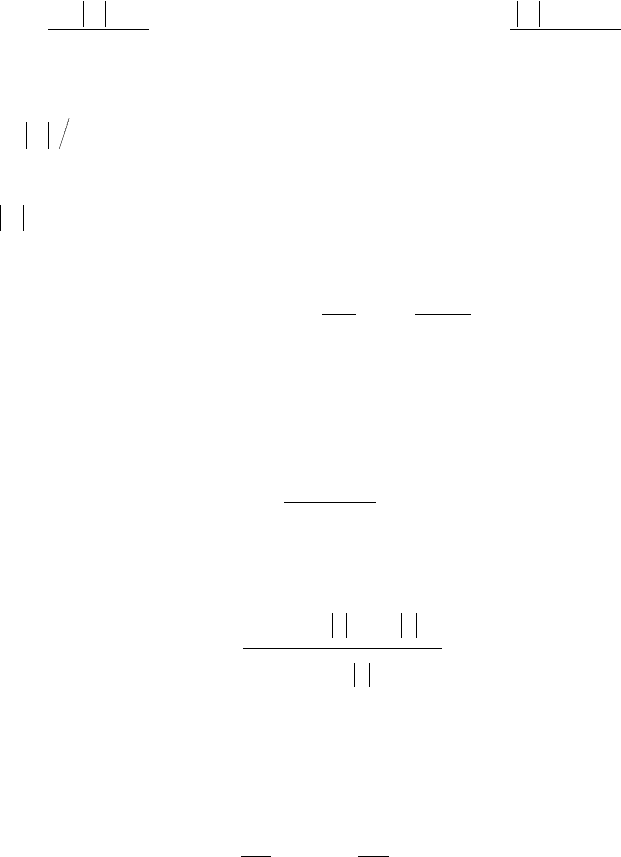

they have used consistently and satisfactorily for all hydrocarbon liquids. Figure 9.3 shows the solu-

tion

of (W/2V)

c

versus K for f = 0.7125, which demonstrates the sensitivity on K.

From the discussion in Section 9.2.4, we have learned that the most important criterion for local-

ization is the imaginary part of self-energy. If it is zero, the state would be localized. If not, the

state would be delocalized. Since the imaginary part of the self-energy cannot be zero and nonzero

at the same time, a state at a given energy is either localized or delocalized, but cannot be both.

At a given energy, more and more states would get localized as the disorder is increased, until at

a critical disorder (designated σ

c

≡ (W/2V)

c

) all eigenstates would be so localized that no diffusion

can ensue. This is called Anderson’s theorem. It applies for static disorder, without contact with a

heat bath, in a TBA of the independent particle picture. The associated phenomenon is known as

Anderson

localization.

Anderson’s

localization theory has been employed in several important applications using the

scaling procedure. Our purpose here is twofold (Hug and Mozumder, 2008): (1) to estimate the

fraction of delocalized states in a uid as a function of the disorder parameter and (2) to givea

quantitative measure of the extent, ξ, of localization of the excess electron’s spatial envelope,

4 6 8 10 12

0

10

20

30

(W/2V)

c

K

f = 0.7125

Figure 9.3 Critical disorder (W/2V)

c

as a function of connectivity (K) for the numerical factor f = 0.7125.

Agreement of the results of a percolation model (Shante and Kirkpatrick 1971) with the scaling theory of

Chang

etal. (1990) is obtained for f = 0.7125.

218 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

exp(−r/ξ). Thelatter has been written by Mott (1967) as sin(kr)exp(−r/ξ), where k is proportional to

the

momentum of the localized electron.

For

disorders less than the critical value (σ ≤ σ

c

), the eigenstates are either localized or delo-

calized, in the ascending order of energy, that is, the parameter ξ of the electron’s wave function

envelope is a monotonically increasing function of energy E. Since long transport requires some

delocalization of the electron to acquire signicant mobility, it is apparent that, for this purpose, the

electron must have energy E ≥ E

c

, a critical value for the disordered medium. Therefore, the criti-

cal energy is a function of the disorder E

c

(σ), or, by inversion, the critical disorder is a function of

energy

σ

c

(E), which is called the mobility edge trajectory.

The parameter ξ of the wave function envelope, often called the correlation length of the local-

ized eigenstates, diverges (ξ → ∞) at a given disorder as the energy approaches the critical value

from

below according to an index law given by the following equation:

ξ σ

ν

( ) ~ [ ( ) ] ( ) .E E E E E

c c

− ≤

−

(9.9)

At a given energy, it also diverges as the disorder approaches the critical value from above (σ → σ

c

),

as

given in the following equation:

ξ σ σ σ σ σ( ) ~ [ ] ( ) .− ≥

−

c c

v

(9.10)

It is an important fundamental result of the scaling theory that the critical exponent, v, is the same

in Equations 9.9 and 9.10 (Chang etal., 1990 and references therein). However, there is considerable

disagreement in the literature about the values of v obtained by numerical and scaling methods,

indicating only a range between ∼0.6 and 1.95. It probably depends somewhat upon the nature of the

lattice, but it should be the same in a given class of liquids. Chayes etal. (1986) have presented theo-

retical argument to show that in three dimensions, ν ≥ 2/3. Following Chang etal. (1990) and some

other authors, we have consistently used ν ≈ 1 for liquid hydrocarbons (Hug and Mozumder, 2008).

Using a symmetry argument, Chang etal. (1990) proposed a quadratic expression for the mobil-

ity edge trajectory in their numerical study, that is, σ

c

(E) = σ

c

− AE

2

, where A is a positive constant

and E is not very large (note that in their case, the mobility edge is positive). For our negative mobil-

ity

edge trajectory, we have used the following ansatz:

σ

σ

c

c

E E

E

( )

exp ,= − −

1

1

2

(9.11)

where E

1

is a characteristic energy that has been interpreted for alkane liquids (Hug and Mozumder,

2008). This ansatz is convenient in the sense that it gives σ

c

(0) = 0 (no state localized at zero dis-

order) and σ

c

(∞) = σ

c

(all states localized at critical disorder). Additionally, at small values of E,

σ

c

(E) = σ

c

[E/E

1

]

2

, which satises the quadratic symmetry requirement of Chang etal. (1990). This

quadratic symmetry has been supported by a numerical study by Bulka etal. (1987) for diagonally

disordered systems with non-pathological site energy distribution. Further, the quadratic mobility

edge trajectory has been construed by Chang etal. (1990) to imply that the fraction of delocalized

states

at disorder σ should be given by

f

c

c

( ) ( ).

/

σ

σ

σ

σ σ= −

≤1

1 2

(9.12)

Note that Equation 9.12 gives just the fraction of initially delocalized states, irrespective of their

occupation. These states have been called the doorway states, from which their nal transition to

quasi-free

or trapped states may ensue (Hug and Mozumder, 2008).

Electron Localization and Trapping in Hydrocarbon Liquids 219

9.2.6 application to liQuid hydrocarbonS

The starting point for application to liquid hydrocarbons is conveniently chosen to be the calculation

of connectivity, K = Z − 1, where Z is the number of nearest neighbors. The latter is obtainable from

the pair correlation function g(r), for which we prefer to rely upon the experimental data of x-ray or

neutron scattering at small angles. There are several equivalent and alternative mathematical forms

connecting g(r) with the experimental, normalized scattered intensity, I(k), of the incident radiation

at momentum transfer ħk. They all originate from the early work of Zernike and Prins (1927), of

which

a simplied version given below is useful (Warren, 1933):

g r

r

k I k kr dk( ) [ ( ) ]sin( ) ,= +

−

∞

∫

ρ

π

1

2

1

2

0

(9.13)

where

ρ

is the liquid density per unit volume

g(r) is the radial pair density distribution function at separation r

k

= 4π sin θ/λ

2θ is the scattering angle

λ

is the wavelength of the radiation

I(k) is obtainable from experiment, after careful elimination of intramolecular scattering, so that g(r)

may correctly refer to the intermolecular distribution (Warren, 1933; Kuchitsu, 1968; Narten, 1979).

The upper limit of integration in Equation 9.13 may be taken as 2π/λ, or often less, without appreciable

error (Pierce, 1935). Some examples of g(r), so obtained for liquid hydrocarbons, have been discussed

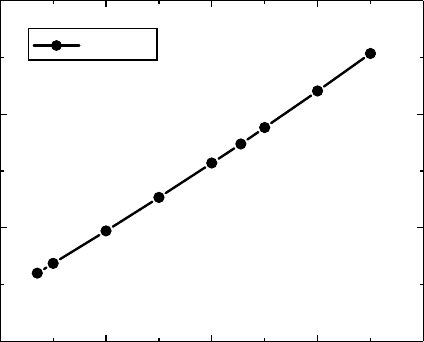

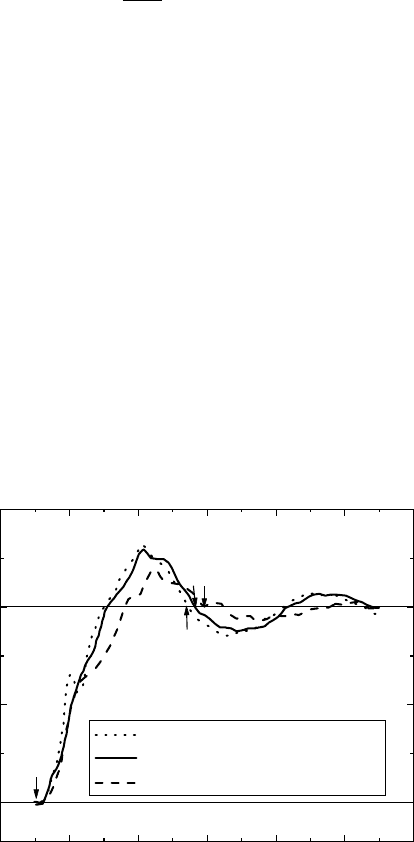

by Hug and Mozumder (2008). Figure 9.4 gives the radial distribution function in neopentane at three

different temperatures obtained by Narten (1979), while Figure 9.5 shows our calculation for isopen-

tane, using the experimental data of Stephens (1986), following the procedure of Narten (1979). In

these gures, g(r) is normalized to the liquid density. From knowledge of g(r), the number of nearest

neighbors, Z, is computed according to Equation 9.1. There is no difculty about r

min

, that is, the lower

limit of the integral over r in Equation 9.1, as eliminating the intramolecular scattering automatically

2.0 4.0 6.0 8.0 10.0 12.0 14.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

g (r)

r (Å)

256 K; ρ

0

= 0.00528 molecules Å

–3

298 K; ρ

0

= 0.00488 molecules Å

–3

423 K; ρ

0

= 0.00304 molecules Å

–3

Figure 9.4 Intermolecular pair (density) distribution in liquid neopentane from the experimental data of

Narten, normalized to the average number density. Number of nearest neighbors is obtained by integration

between the vertical lines. The results are 8.6, 8.7, and 7.1 molecules Å

−3

, for 256, 298, and 423K, respectively.