Hancock G.J., Murray Th.M., Ellifritt D.S. Cold-Formed Steel Structures to the AISI Specification

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Try

P

u

7:35 kips

M

uy

P

u

x

cea

7:04 kip-in:

P

Ey

As

ey

144:1 kips

a

y

1 ÿ

P

u

P

Ey

0:949 Eq: C5:2:2-5

P

u

f

c

P

n

C

my

M

uy

f

b

M

ny

a

y

7:35

0:85 15:75

7:04

0:90 18:32 0:949

1:0 Eq: C5:2:2-1

P

u

f

c

P

no

M

uy

f

b

M

ny

7:35

0:85 19:74

7:04

0:90 18:32

0:865 < 1:0

Eq: C5:2:2-2

Hence, the required axial strength for a load applied

eccentrically at web is

P

u

7:35 kips

REFERENCES

8.1 Trahair, N. S. and Bradford, M. A., The Behaviour

and Design of Steel Structures, 3rd ed., Chapman and

Hall, London, 1998.

8.2 Peko

È

z, T. and Winter, G., Torsional-¯exural buckling

of thin-walled sections under eccentric load, Journal

of the Structural Division, ASCE, Vol. 95, No. ST5,

May 1969, pp. 1321±1349.

8.3 Jang, D. and Chen, S., Inelastic Torsional-Flexural

Buckling of Cold-Formed Open Section under

Eccentric Load, Seventh International Specialty

Conference on Cold-Formed Steel Structures, St

Louis, MO, November, 1984.

Chapter 8

248

8.4 Rack Manufacturers Institute, Speci®cation for the

Design, Testing and Utilization of Industrial Steel

Storage Racks, Materials Handling Institute, Char-

lotte, NC, 1997.

8.5 Peko

È

z, T., Uni®ed Approach for the Design of Cold-

Formed Steel Structures, Eighth International Speci-

alty Conference on Cold-Formed Steel Structures, St

Louis, MO, November, 1986.

8.6 Loh, T. S., Combined Axial Load and Bending in Cold-

Formed Steel Members, Ph.D. thesis, Cornell Univer-

sity, February 1985, Report No. 85-3.

Members in Combined Axial Load and Bending

249

9

Connections

9.1 INTRODUCTION TO WELDED

CONNECTIONS

Welded connections between thin-walled cold-formed steel

sections have become more common in recent years despite

the shortage of design guidance for sections of this type.

Two publications based on work at Cornell University, New

York (Ref. 9.1), and the Institute TNO for Building Mater-

ials and Building Structures in Delft, Netherlands (Ref.

9.2), have produced useful test results from which design

formulae have been developed. The design rules in the AISI

Speci®cation were developed from the Cornell tests.

However, the more recent TNO tests add additional infor-

mation to the original Cornell work, and so the results and

design formulae derived in Refs. 9.1 and 9.2 are covered in

this chapter even though the AISI Speci®cation is based

solely on Ref. 9.1.

251

Sheet steels are normally welded with conventional

equipment and electrodes. However, the design of the

connections produced is usually different from that for

hot-rolled sections and plate for the following reasons:

(a) Stress-resisting areas are more dif®cult to de®ne.

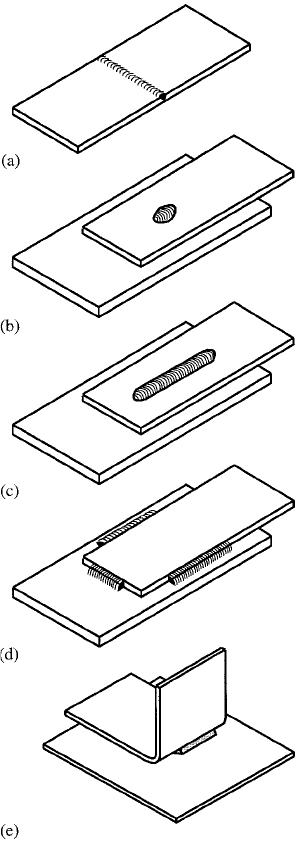

(b) Welds such as the arc spot and seam welds in

Figures 9.1c and d are made through the welded

sheet without any preparation.

(c) Galvanizing and paint are not normally removed

prior to welding.

(d) Failure modes are complex and dif®cult to cate-

gorize.

The usual types of fusion welds used to connect cold-

formed steel members are shown in Figure 9.1, although

groove welds in butt joints may be dif®cult to produce in

thin sheet and are therefore not as common as ®llet, spot,

seam, and ¯are groove welds. Arc spot and slot welds are

commonly used to attach cold-formed steel decks and

panels to their supporting frames. As for conventional

structural welding, it is general practice to require that

the weld materials be matched at least to the strength level

of the weaker member. Design rules for the ®ve weld types

in Figures 9.1a±e are given as Sections E2.1±E2.5, respec-

tively, in the AISI Speci®cation.

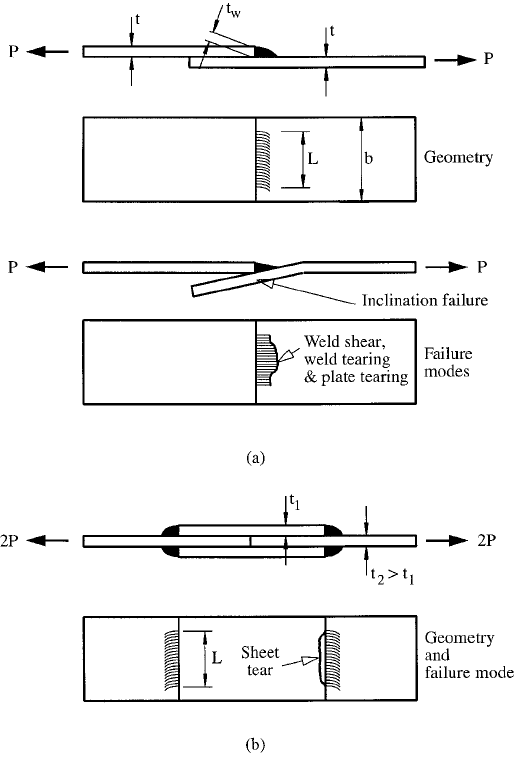

Failure modes in welded sheet steel are often compli-

cated and involve a combination of basic modes, such as

sheet tearing and weld shear, as well as a large amount of

out-of-plane distortion of the welded sheet. In general, ®llet

welds in thin sheet steel are such that the leg length on the

sheet edge is equal to the sheet thickness, and the other leg

is often two to three times longer. The throat thickness (t

w

in Figure 9.2a) is commonly larger than the thickness (t)of

the sheet steel, and, hence, ultimate failure is usually

found to occur by tearing of the plate adjacent to the weld

or along the weld contour. In most cases, yielding is poorly

de®ned and rupture rather than yielding is a more reliable

Chapter 9

252

FIGURE 9.1 Fusion weld types: (a) groove weld in butt joint;

(b) arc spot weld (puddle weld); (c) arc seam welds; (d) ®llet welds;

(e) ¯are-bevel groove weld.

Connections

253

criterion of failure. Hence, for the ®llet welds tested at

Cornell University and Institute TNO, the design formulae

are a function of the tensile strength (F

u

) of the sheet

material and not of the yield point (F

y

). This latter formula-

tion has the added advantage that the yield strength of the

FIGURE 9.2 Transverse ®llet welds: (a) single lap joint (TNO

tests); (b) double lap joint (Cornell test).

Chapter 9

254

cold-formed steel in the heat-affected zone does not play a

role in the design and, hence, need not be determined.

As a result of the different welding procedures

required for sheet steel, the speci®cation of the American

Welding Society for Welding Sheet Steel in Structures (Ref.

9.3) should be closely followed and has been referenced in

the AISI Speci®cation. The fact that a welder may have

satisfactorily passed a test for structural steel welding does

not necessarily mean that he can produce sound welds on

sheet steel. The welding positions covered by the Speci®ca-

tion are given for each weld type in Table E2 of the

Speci®cation.

For the welded connection in which the thickness of

the thinnest connected part is greater than 0.18 in., the

design rules in the AISC ``Load and Resistance Factor

Design for Structural Steel Buildings'' (Ref. 1.1) should be

used. The reason for this is that failure through the weld

throat governs for thicker sections rather than sheet tear-

ing adjacent to the weld in thinner sections.

In the case of ®llet welds and ¯are groove welds,

failure through the weld throat is checked for plate thick-

nesses greater than 0.15 in. as speci®ed in Sections E2.4

and Section E2.5.

9.2 FUSION WELDS

9.2.1 Groove Welds in Butt Joints

In the AISI Speci®cation the nominal tensile and compres-

sive strengths and the nominal shear strength are speci®ed

for a groove butt weld. The butt joint nominal tensile or

compressive strength (P

n

) is based on the yield point used

in design for the lower-strength base steel and is given by

P

n

Lt

e

F

y

9:1

where L is the length of the full size of the weld and t

e

is the

effective throat dimension of the groove weld. A resistance

Connections

255

factor of 0.90 is speci®ed for LRFD and a factor of safety of

2.5 is speci®ed for ASD, and they are the same as for a

member.

The nominal shear strength (P

n

) is the lesser of the

shear on the weld metal given by Eq. (9.2) and the shear on

the base metal given by Eq. (9.3):

P

n

Lt

e

0:6F

xx

9:2

P

n

Lt

e

F

y

3

p

9:3

where F

xx

is the nominal tensile strength of the groove weld

metal. A resistance factor of 0.8 for LRFD is used with Eq.

(9.2), and a resistance factor of 0.9 for LRFD is used with

Eq. (9.3) since it applies to the base metal. Equation (9.2)

applies to the weld metal and therefore has a lower resis-

tance factor than Eq. (9.3). For ASD, a factor of safety of 2.5

is used with both equations.

9.2.2 Fillet Welds Subject to Transverse

Loading

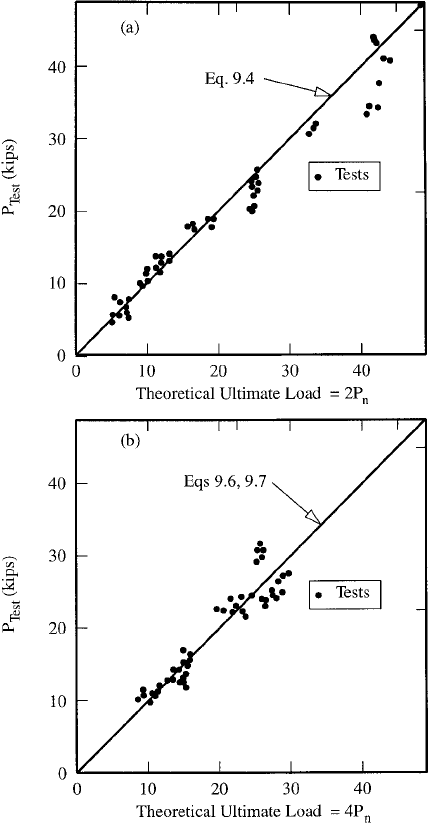

The Cornell test data for ®llet welds, deposited from

covered electrodes, was produced for the type of double

lap joints shown in Figure 9.2b. These joints failed by

tearing of the connected sheets along or close to the contour

of the welds, or by secondary weld shear. Based on these

tests, Eq. (9.4) was proposed to predict the connection

strength:

P

n

tLF

u

9:4

where t is the sheet thickness, L is the length of weld

perpendicular to the loading direction, and F

u

is the tensile

strength of the sheet. The results of these tests are shown

in Figure 9.3a for all failure modes where they are

compared with the prediction of Eq. (9.4). The values on

the abscissa of Figure 9.3a are 2P

n

since the joints tested

were double lap joints. A resistance factor (f) of 0.60 for

Chapter 9

256

FIGURE 9.3 Fillet weld tests (Cornell): (a) transverse (Figure

9.2b); (b) longitudinal (Figure 9.4b).

Connections

257