Gulian A.M., Zharkov G.F. Nonequilibrium Electrons and Phonons in Superconductors

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

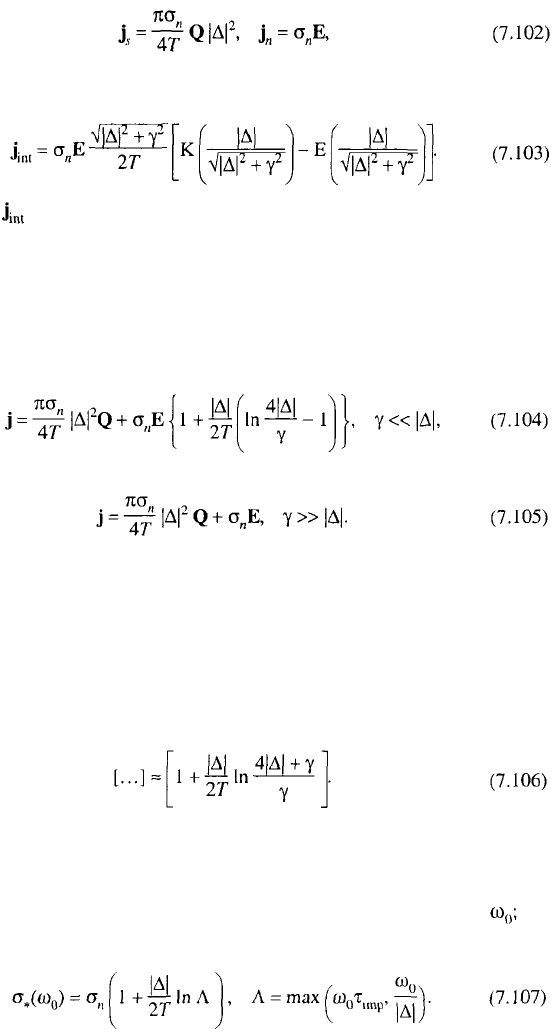

SECTION 7.2. INTERFERENCE CURRENT 171

and the “interference” component is

The quantity (7.103) has properties of both the superconducting condensate and

the normal excitations. In fact, it describes some interference of two types of motion

occurring in the electron subsystem of the superconductor.

A comparison of (7.103) with (7.102) shows that the interference component

of the current is not always negligible. Using the asymptotic forms (7.99) and

(7.100) of the elliptic integrals, one can easily show that (7.98) takes the following

forms in the specified limiting cases

Equation (7.105) coincides with the expression for the gapless superconductor (see

Sect. 2.3); in this case the current consists of the normal and superconducting

components only. Thus the interference term in the “finite-gap” superconductor

stems from the strong correlation between the system of single-particle excitations

and the pair condensate. This correlation vanishes in a gapless regime.

Using (7.104) and (7.105), we can write the following rough approximation,

which reflects the behavior of the functions in brackets in (7.103):

This approximation is convenient for practical calculations.

Note that a logarithmic renormalization of conductivity, analogous to (7.107),

appears in the theory of both linear

23,24

and nonlinear

25,26

responses of a supercon-

ductor in a time-varying external electromagnetic field of the frequency for

example,

172 CHAPTER 7. TIME-DEPENDENT GINZBURG–LANDAU EQUATIONS

Such a logarithmic renormalization of conductivity also reflects the interference

between normal and superfluid motions. Although the parameter near is

small, the corrections might be not negligible, because the logarithmic factor can

in principle be large. We should also mention that the interference described above

is closely related to the “drag” process investigated by Shelankov.

27

7.2.3.

More

Complete

Expressions

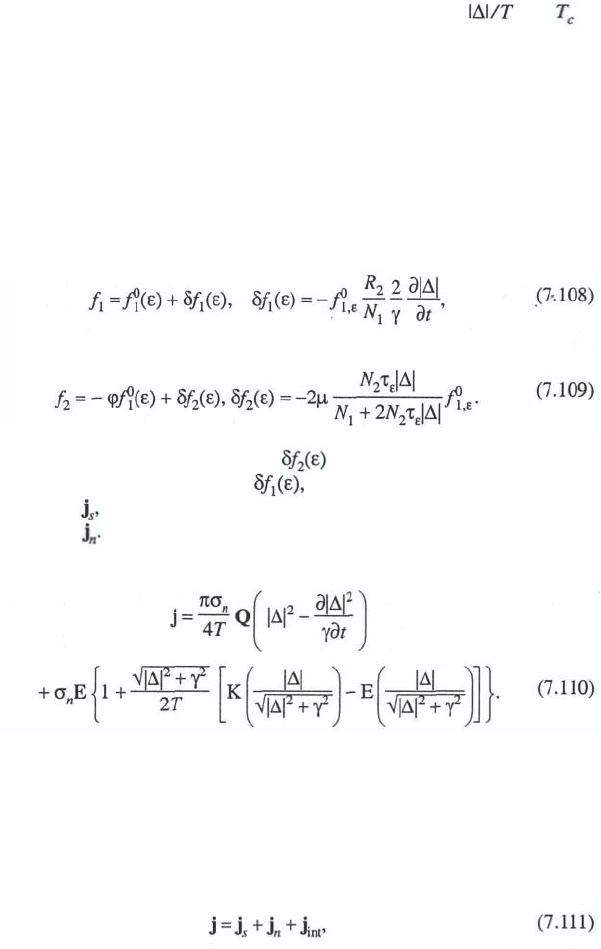

We used above the equilibrium approximation for the functions f

1

and f

2

. To

find these functions [Eqs. (7.43) and (7.44)] in the time-dependent theory, the

nonequilibrium contributions must be taken into account. They may be expressed

in the form

The current component due to the function in (7.88) is vanishingly small and

can be ignored. However, the function whose contribution though small in

comparison with is dissipative. In general, this component need not be small in

comparison with The resulting current is given by the following expression in

the “local equilibrium approximation”:

This expression should be used in the Ginzburg–Landau equations instead of those

presented in Refs. 2–6.

7.2.4. Interference Current in Complete Form

The expression for current in the Ginzburg–Landau regime can be written in

the form

where

SECTION 7.2. INTERFERENCE CURRENT 173

This current (7.111) enters the Maxwell set of equations, which should be supple-

mented with two equations ensuing from (7.45). We will write down

these equations and prove the completeness of the resulting set.

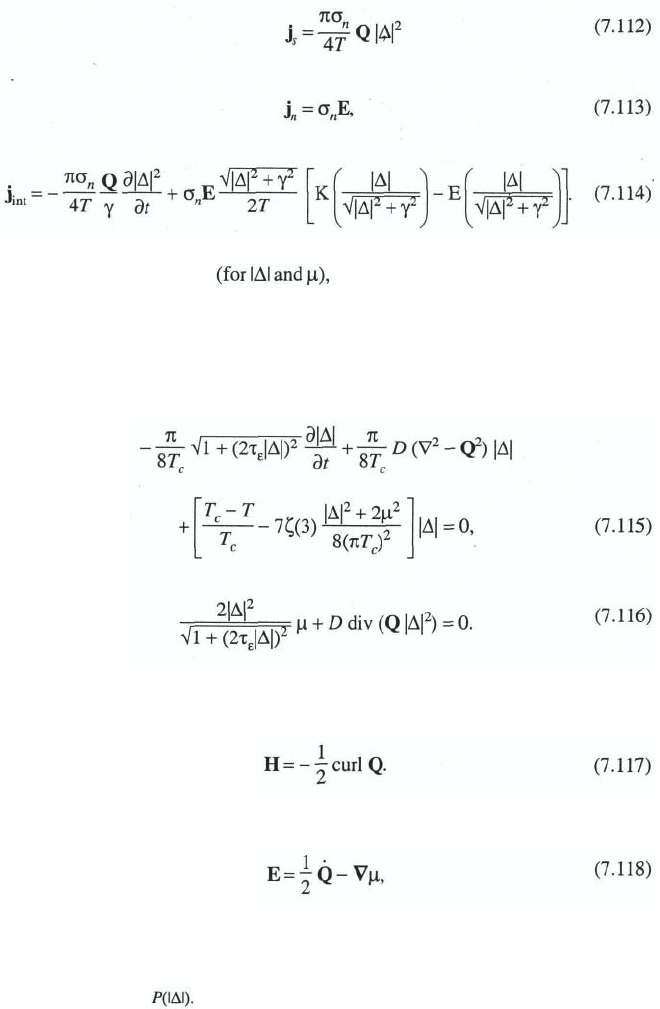

7.2.5. Full Set of Equations

After separating the real and imaginary parts of (7.45) one finds

*

:

The superfluid momentum Q enters Eqs. (7.115) and (7.116). It is defined by the

relation (7.82) and is connected with the magnetic field strength H by

Recalling definition (7.86) of the electric field,

it can be easily seen that two of the Maxwell equations

*We also omit the term

174 CHAPTER 7. TIME-DEPENDENT GINZBURG–LANDAU EQUATIONS

are satisfied identically due to (7.117) and (7.118). Note that in the equilibrium

Ginzburg–Landau scheme Eq. (7.116) coincides with the continuity equation

(because in that case). In nonequilibrium conditions, Eq.

(7.116) and the continuity equation

are independent. The second pair of the Maxwell equations may be written as

where and the charge density induced in a nonequilibrium superconduc-

tor by the external field is expressed in terms of the gauge-invariant potential by

(7.52). Thus the charge density, the current, and the electric and magnetic fields

may be expressed in terms of and their derivatives. To calculate these (five)

quantities, we have two scalar equations [(7.115) and (7.116)] and the vector

equation (7.121). The scalar (the dielectric susceptibility) entering (7.121) re-

quires one more independent equation, which plays by the continuity equation

(7.120) [or, equivalently, Eq. (7.122)].

7.2.6. Boundary Conditions

This set of equations must be supplemented by the boundary conditions, which

may differ in various problems. For instance, at the boundary between a supercon-

ductor and a normal metal, one can write

where is some constant, usually taken as is an equilibrium

approximation and is the coherence length). In nonequilibrium conditions,

may differ from this value (see Ref. 28), but remains of an order of unity. At the

superconductor–vacuum boundary, the following conditions are reasonable:

where

n

is the vector normal to the superconductor’s surface. One should also obtain

the continuity of the magnetic field

H

and of the tangential component of the electric

field Some other boundary conditions are discussed in Chap. 9.

SECTION 7.3. VISCOUS FLOW OF VORTICES 175

We conclude this section by mentioning that is not necessarily a continuous

function of coordinates and time and may suffer discontinuity, so the solutions of

the equations given above may lie in a class of piecewise smooth functions.

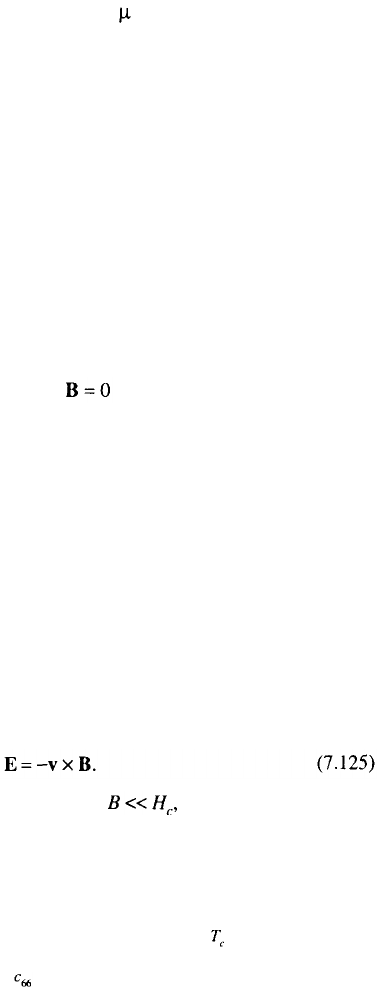

7.3. VISCOUS FLOW OF VORTICES

7.3.1. Abrikosov Vortices

As was shown in Chap. 1, in Type II superconductors, the surface energy at the

boundary between superconducting and normal phases is negative. This results in

the presence of normal domains in Type II superconductors placed in a magnetic

field, which penetrates these domains. In isotropic homogeneous superconductors,

the domains form a regular structure (a vortex lattice*). Such a vortex state was

predicted by Abrikosov

37

(see also Ref. 38) on the basis of the Ginzburg–Landau

theory. The magnetic field penetrating into the vortex core is screened by the

London currents, so the magnetic induction in the intermediate space between

vortices. With transport current passing through such a system, the Lorentz force

appears and acts on moving charges. In turn, an equal but opposite force acts on the

vortex system and pushes the latter into motion. Because the velocity of the vortex

lattice cannot increase indefinitely, the flow of vortices must have a viscous

character and be accompanied by energy dissipation. If this motion is stopped some

way, for example, by the trapping of vortices on imperfections of a crystalline lattice

(“pinning”), then the transport current remains superfluid. If pinning does not occur,

then ultimately the dissipation energy is eliminated from the kinetic energy of the

transport current, which ceases to be superfluid. To maintain this current, an electric

field should exist along the current direction. In this manner a resistive current state

is formed. We will use the nonstationary Ginzburg–Landau equations to describe

vortex motion in superconductors.

The velocity

v

of vortex lattice motion is connected to the vectors

E

and

B

by

the relation

We will consider only the weak magnetic fields: i.e., we will consider the

problem of the motion of an isolated vortex.

*

In analogy to the case of a crystalline lattice, the vortex lattice can melt. This phenomenon was predicted

by Eilenberger

30

(and Fisher

31

). It was demonstrated first in the high-temperature superconductors

32

and afterwards in niobium.

33

The reason it was not noticed earlier in low superconductors is the

narrowness of the temperature range of the liquid phase. Theoretical considerations, based on the Born

34

criterion (the vanishing of the shear modulus at the melting point) are applicable to vortex melting

35

and allow such tiny features of the phase transition as the lattice premelting to be considered.

36

176 CHAPTER 7. TIME-DEPENDENT GINZBURG–LANDAU EQUATIONS

7.3.2. Effective Conductivity: Definition

The immediate task is to obtain effective conductivity, which connects the

transport current E with the electric field E. To solve this problem we

use the method proposed by (see also Ref. 40).

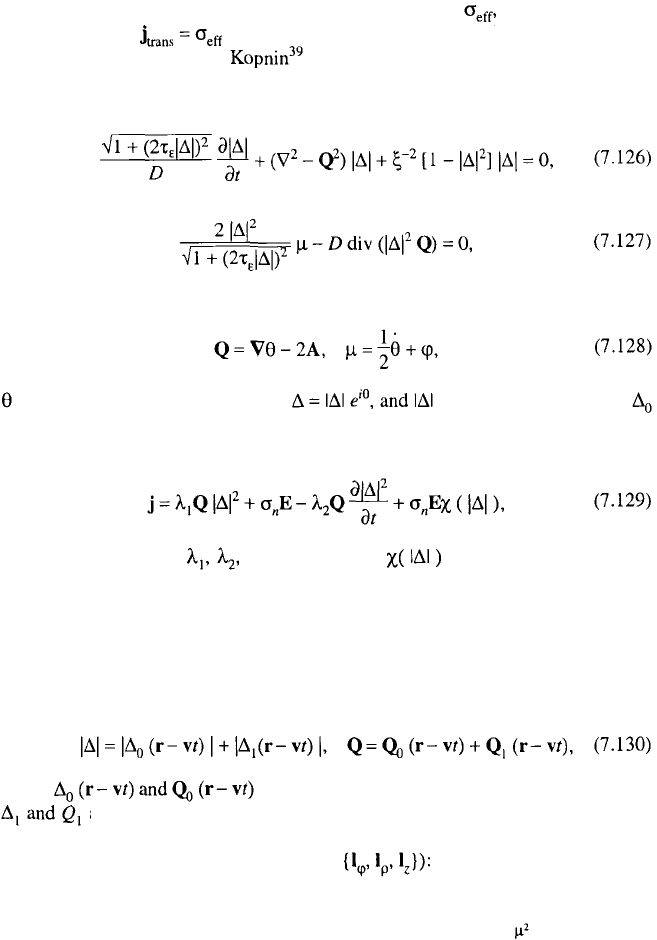

We will apply the time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau equations (7.115) and

(7.116) in the form

*

where

is the phase of an order parameter is measured in the units

(7.50).

The expression for the current is

where the coefficients and the function are obviously defined by

comparing (7.111) to (7.114), with (7.129).

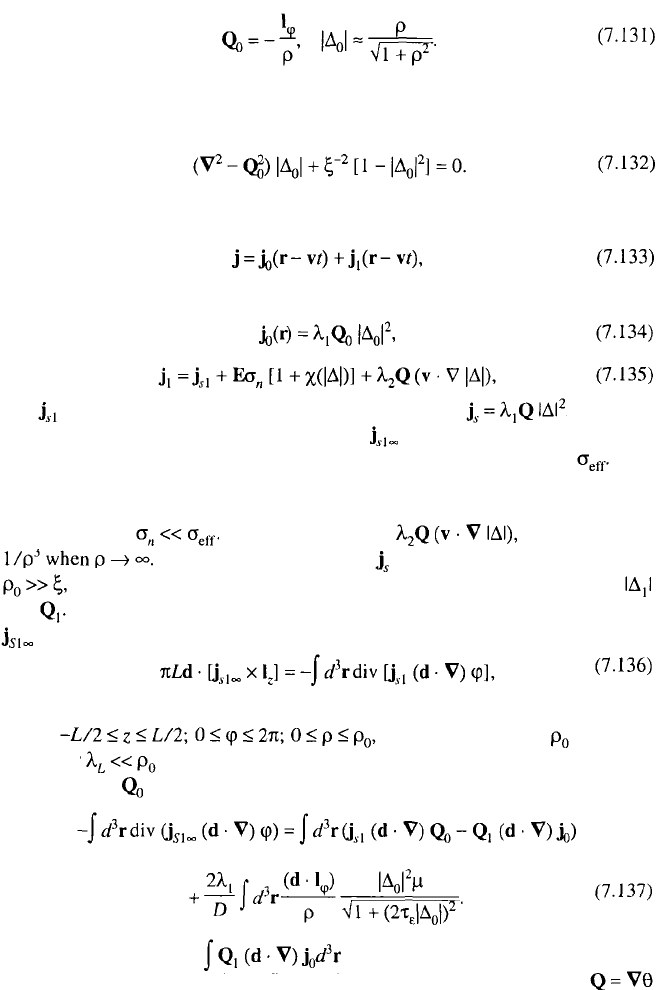

7.3.3. Low-Velocity Approximation

If the velocity of vortex motion is small, then the solution of the system (7.126)

and (7.127) may be presented as

where are the Galilean transformed static solutions

37

and

are the corrections, which are proportional to

v

and arise as a result of

deformation of the vortex structure during the motion. The static solutions are (we

use here the cylindrical frame of reference

*

We ignore here the nonequilibrium phonon field, omitting also in (7.45) the term , which is quadratic

in

E.

SECTION 7.3. VISCOUS FLOW OF VORTICES 177

The approximate expression (7.131) for the order parameter modulus follows from

the equation

In analogy to (7.130) we have the expression for the current

where

and is the correction to the superconducting current . For large

distances from the vortex core, the correction represents the transport current

flowing in the superconductor, and determines the effective conductivity Note

that strictly speaking, the contributions of normal and interference currents in

(7.135) should also be taken into account. However, these contributions are

small, because As to the value of it decreases as

Because the corrections to are needed only at the distances

it is not necessary to have the exact expressions for the quantities

and Instead, we will use a method

39

that allows us to express the solution

in terms of static solution. One can easily verify the equality

where the integration (in the cylindrical frame of reference) is restricted by the

region and the polar radius obeys the

inequality

.The vector d is as yet arbitrary. The right side of (7.136), using

the expression (7.131) and Eq. (7.127), can be transformed to

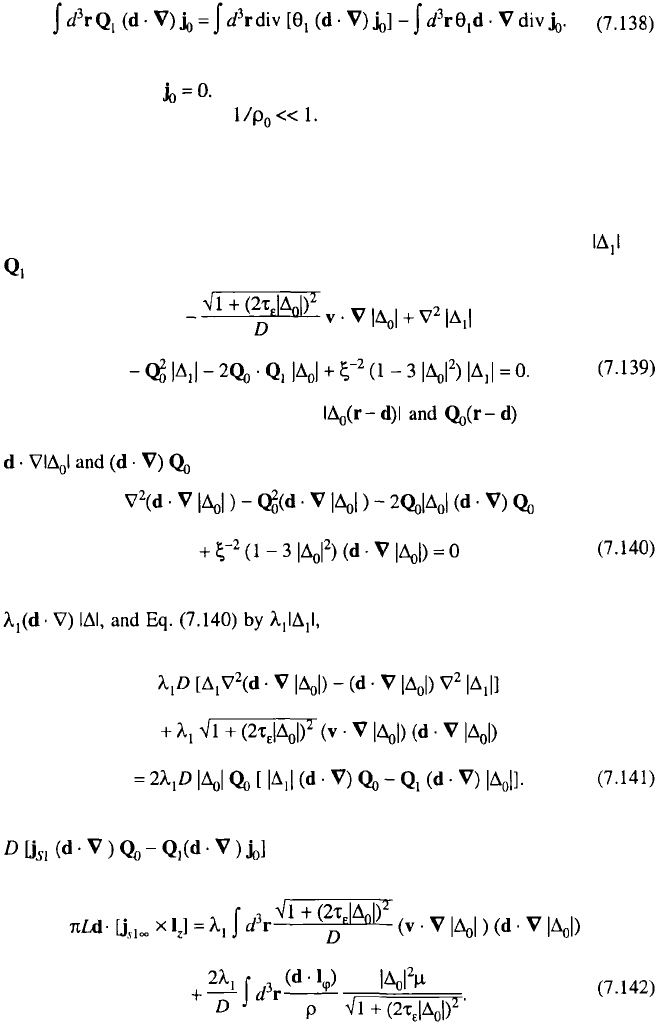

We have added a term into (7.137), which disappears upon

integration. Indeed, from the definition in Eq. (7.128), it follows that

(dropping the vector potential

A

). Thus:

178 CHAPTER 7. TIME-DEPENDENT GINZBURG–LANDAU EQUATIONS

The second term on the right side of Eq. (7.138) vanishes owing to the electroneu-

trality condition div As for the first term, it transforms into a surface integral,

which is small in parameter,

7.3.4. Linearized Equations

On the basis of Eqs. (7.126) and (7.132) we can transform the first integral on

the right side of (7.137). From Eq. (7.126) it follows that the quantities and

obey the linearized equation

Taking into account that the functions are translational

invariant and satisfy the stationary equation (7.132), one finds that quantities

must satisfy the linearized static equation

(the vector d is now assumed to be small). Multiplying Eq. (7.139) by

subtracting the first from the second, we

obtain

One can see now that the right side of Eq. (7.141) is equal to

. Thus, from the relations (7.136), (7.137), and

(7.141) it follows that:

SECTION 7.3. VISCOUS FLOW OF VORTICES 179

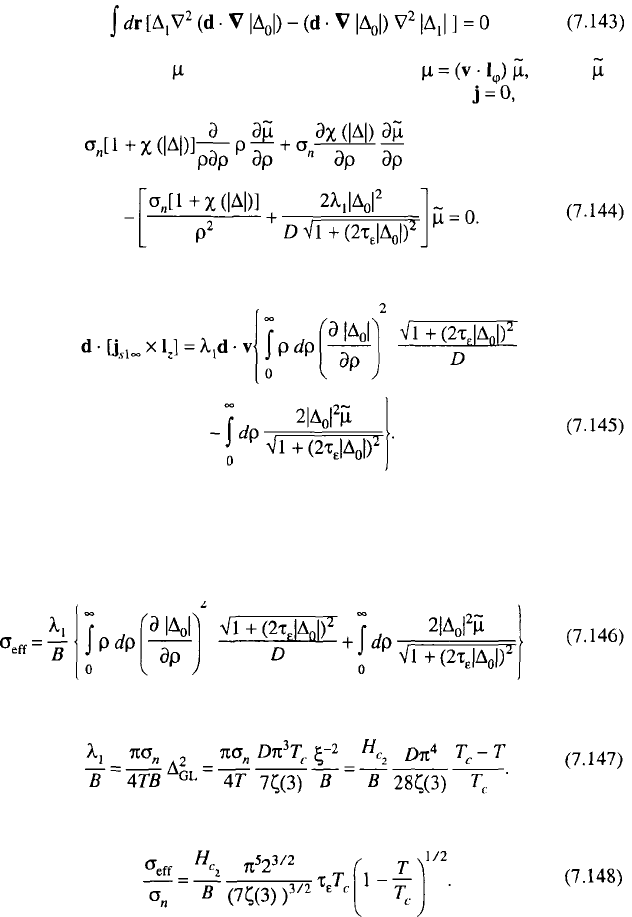

In deriving Eq. (7.142) the relation

was used. The quantity may be written in the form where is

governed by (7.127) and by the electroneutrality condition div from which

Calculating in (7.142) the angle integrals, we arrive at

7.3.5. Effective Conductivity: Results

Finally, the effective conductivity follows from (7.145) and (7.125):

where

Neglecting in (7.144) the small second integral, we get

This result coincides exactly with that of Larkin and Ovchinnikov,

12

obtained by

direct solution of the generalized kinetic equation (7.1). Besides its self-sufficient

180 CHAPTER 7. TIME-DEPENDENT GINZBURG–LANDAU EQUATIONS

value, the example considered demonstrates the possibility of using TDGL equa-

tions to describe nonequilibrium phenomena in superconductors.

7.4. FLUCTUATIONS

We will consider here some characteristic features of fluctuational corrections

to self-consistent treatments of superconductivity, such as GL or BCS theory. This

reveals the applicability limits of the self-consistent approach.

7.4.1. Ginzburg's Number

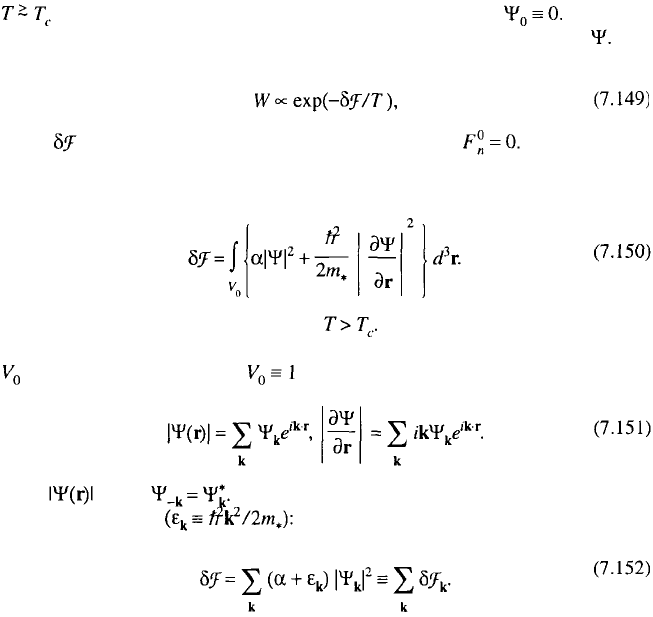

To elucidate the role of fluctuations, we will go back to the free energy

functional considered in Sect. 1.2. For simplicity we will perform calculations at

for the normal phase, where the equilibrium value is Then it is

convenient to denote the fluctuating value of the order parameter as The

fluctuation probability is governed by the expression

where is defined by Eqs. (1.46), (1.45), and (1.31), with Since we expect

the fluctuations to be small, it is sufficient to keep the second-order expansion terms

in the free energy functional:

Both terms are positive in (7.150), since

Let us now make a Fourier expansion of the fluctuating quantities in the volume

(for simplicity we will take below):

Since is real, Substituting (7.151) into (7.150) and integrating over

the volume, we find

As follows from (7.152), (7.149), and (7.152), fluctuations with different values of

k are statistically independent.