Gregersen E. (editor) The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

50

about relative frequencies of occurrence in a large number

of cases but are not predictions about a given individual.

expeRiMenTs, saMple space,

evenTs, and equally likely

pRobabiliTies

Applications of probability theory inevitably involve

simplifying assumptions that focus on some features of a

problem at the expense of others. Thus, it is advantageous

to begin by thinking about simple experiments, such as

tossing a coin or rolling dice, and to see how these appar-

ently frivolous investigations relate to important scientific

questions.

Applications of Simple

Probability Experiments

The fundamental ingredient of probability theory is an

experiment that can be repeated, at least hypothetically,

under essentially identical conditions and that may lead to

different outcomes on different trials. The set of all pos-

sible outcomes of an experiment is called a sample space.

The experiment of tossing a coin once results in a sample

space with two possible outcomes: heads and tails. Tossing

two dice has a sample space with 36 possible outcomes,

each of which can be identified with an ordered pair (i, j),

where i and j assume one of the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and

denote the faces showing on the individual dice. It is

important to think of the dice as identifiable (say by a dif-

ference in colour), so that the outcome (1, 2) is different

from (2, 1). An event is a well-defined subset of the sample

space. For example, the event “the sum of the faces show-

ing on the two dice equals six” consists of the five outcomes

(1, 5), (2, 4), (3, 3), (4, 2), and (5, 1).

51

7

Probability Theory 7

A third example is to draw n balls from an urn contain-

ing balls of various colours. A generic outcome to this

experiment is an n-tuple, where the ith entry specifies the

colour of the ball obtained on the ith draw (i = 1, 2,…, n). In

spite of the simplicity of this experiment, a thorough

understanding gives the theoretical basis for opinion polls

and sample surveys. For example, individuals in a popula-

tion favouring a particular candidate in an election may be

identified with balls of a particular colour, those favouring

a different candidate may be identified with a different

colour, and so on. Probability theory provides the basis for

learning about the contents of the urn from the sample of

balls drawn from the urn. An application is to learn about

the electoral preferences of a population on the basis of a

sample drawn from that population.

Another application of simple urn models is to use

clinical trials designed to determine whether a new treat-

ment for a disease, a new drug, or a new surgical procedure

is better than a standard treatment. In the simple case

in which treatment can be regarded as either success or

failure, the goal of the clinical trial is to discover whether

the new treatment more frequently leads to success than

does the standard treatment. Patients with the disease

can be identified with balls in an urn. The red balls are

those patients who are cured by the new treatment, and

the black balls are those not cured. Usually there is a con-

trol group, who receive the standard treatment. They are

represented by a second urn with a possibly different frac-

tion of red balls. The goal of the experiment of drawing

some number of balls from each urn is to discover on the

basis of the sample which urn has the larger fraction of

red balls. A variation of this idea can be used to test the

efficacy of a new vaccine. Perhaps the largest and most

famous example was the test of the Salk vaccine for polio-

myelitis conducted in 1954. It was organized by the U.S.

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

52

Public Health Service and involved almost two million

children. Its success has led to the almost complete elimi-

nation of polio as a health problem in the industrialized

parts of the world. Strictly speaking, these applications

are problems of statistics, for which the foundations are

provided by probability theory.

In contrast to the experiments previously described,

many experiments have infinitely many possible out-

comes. For example, one can toss a coin until heads

appears for the first time. The number of possible tosses

is n = 1, 2, . . . Another example is to twirl a spinner. For an

idealized spinner made from a straight line segment hav-

ing no width and pivoted at its centre, the set of possible

outcomes is the set of all angles that the final position of

the spinner makes with some fixed direction, equivalently

all real numbers in [0, 2π). Many measurements in the

natural and social sciences, such as volume, voltage, tem-

perature, reaction time, marginal income, and so on, are

made on continuous scales and at least in theory involve

infinitely many possible values. If the repeated measure-

ments on different subjects or at different times on the

same subject can lead to different outcomes, probability

theory is a possible tool to study this variability.

Because of their comparative simplicity, experiments

with finite sample spaces are discussed first. In the early

development of probability theory, mathematicians con-

sidered only those experiments for which it seemed

reasonable, based on considerations of symmetry, to sup-

pose that all outcomes of the experiment were “equally

likely.” Then in a large number of trials, all outcomes

should occur with approximately the same frequency. The

probability of an event is defined to be the ratio of the

number of cases favourable to the event (i.e., the number

of outcomes in the subset of the sample space defining the

event) to the total number of cases. Thus, the 36 possible

53

7

Probability Theory 7

outcomes in the throw of two dice are assumed equally

likely, and the probability of obtaining “six” is the number

of favourable cases, 5, divided by 36, or 5/36.

Now suppose that a coin is tossed n times, and con-

sider the probability of the event “heads does not occur”

in the n tosses. An outcome of the experiment is an n-tuple,

the kth entry of which identifies the result of the kth toss.

Because there are two possible outcomes for each toss,

the number of elements in the sample space is 2

n

. Of these,

only one outcome corresponds to having no heads, so the

required probability is 1/2

n

.

It is only slightly more difficult to determine the prob-

ability of “at most one head.” In addition to the single

case in which no head occurs, there are n cases in which

exactly one head occurs, because it can occur on the first,

second, . . . , or nth toss. Hence, there are n + 1 cases favour-

able to obtaining at most one head, and the desired

probability is (n + 1)/2

n

.

The Principle of Additivity

This last example illustrates the fundamental principle

that if the event whose probability is sought can be repre-

sented as the union of several other events that have no

outcomes in common (“at most one head” is the union of

“no heads” and “exactly one head”), then the probability of

the union is the sum of the probabilities of the individual

events making up the union. To describe this situation

symbolically, let S denote the sample space. For two events

A and B, the intersection of A and B is the set of all experi-

mental outcomes belonging to both A and B and is denoted

A ∩ B; the union of A and B is the set of all experimental

outcomes belonging to A or B (or both) and is denoted

A ∪ B. The impossible event (i.e., the event containing no

outcomes) is denoted by Ø. The probability of an event A

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

54

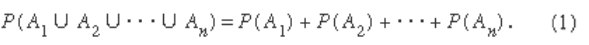

is written P ( A ). The principle of addition of probabilities

is that, if A

1

, A

2

, . . . , A

n

are events with A

i

∩ A

j

= Ø for all

pairs i ≠ j , then

Equation (1) is consistent with the relative frequency

interpretation of probabilities. For, if A

i

∩ A

j

= Ø for all

i ≠ j , the relative frequency with which at least one of the

A

i

occurs equals the sum of the relative frequencies with

which the individual A

i

occur.

Equation (1) is fundamental for everything that fol-

lows. Indeed, in the modern axiomatic theory of

probability, which eschews a defi nition of probability in

terms of “equally likely outcomes” as being hopelessly cir-

cular, an extended form of equation (1) plays a basic role.

An elementary, useful consequence of equation (1) is

the following. With each event A is associated the com-

plementary event A

c

consisting of those experimental

outcomes that do not belong to A . Because A ∩ A

c

= Ø,

A ∪ A

c

= S , and P ( S ) = 1 (where S denotes the sample

space), it follows from equation (1) that P ( A

c

) = 1 − P ( A ).

For example, the probability of “at least one head” in n

tosses of a coin is one minus the probability of “no head,”

or 1 − 1/2

n

.

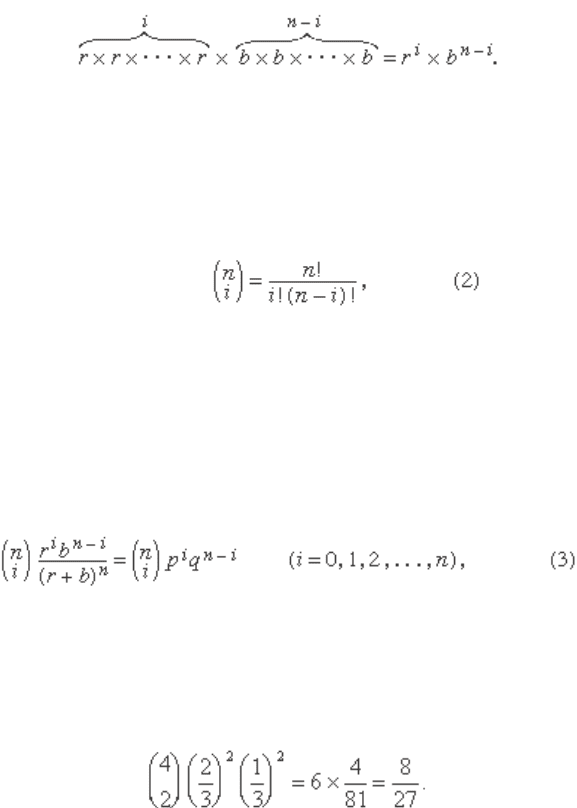

Multinomial Probability

A basic problem fi rst solved by Jakob Bernoulli is to fi nd

the probability of obtaining exactly i red balls in the

experiment of drawing n times at random with replace-

ment from an urn containing b black and r red balls. To

draw at random means that, on a single draw, each of

55

7

Probability Theory 7

the r + b balls is equally likely to be drawn and, because

each ball is replaced before the next draw, there are

( r + b ) ×⋯× ( r + b ) = ( r + b )

n

possible outcomes to the experi-

ment. Of these possible outcomes, the number that is

favourable to obtaining i red balls and n − i black balls in

any one particular order is

The number of possible orders in which i red balls and

n − i black balls can be drawn from the urn is the binomial

coeffi cient

where k ! = k × ( k − 1) ×⋯× 2 × 1 for positive integers k , and

0! = 1. Hence, the probability in question, which equals the

number of favourable outcomes divided by the number of

possible outcomes, is given by the binomial distribution

where p = r /( r + b ) and q = b /( r + b ) = 1 − p .

For example, suppose r = 2 b and n = 4. According to

equation (3), the probability of “exactly two red balls” is

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

56

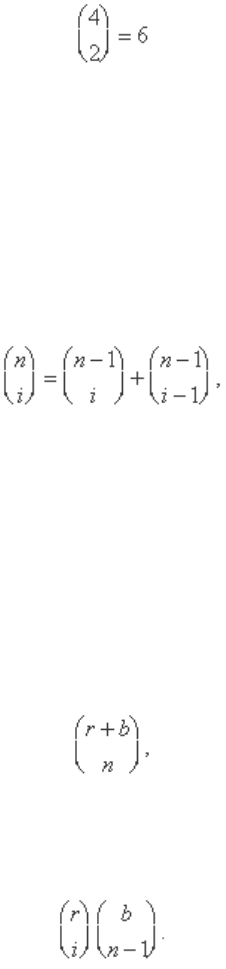

In this case the

possible outcomes are easily enumerated: (rrbb), (rbrb),

(brrb), (rbbr), (brbr), (bbrr). (For a derivation of equation

(2), observe that to draw exactly i red balls in n draws one

must either draw i red balls in the first n − 1 draws and a

black ball on the nth draw or draw i − 1 red balls in the

first n − 1 draws followed by the ith red ball on the nth

draw. Hence,

from which equation (2) can be verified by induction on n.)

Two related examples are (i) drawing without replace-

ment from an urn containing r red and b black balls and (ii)

drawing with or without replacement from an urn con-

taining balls of s different colours. If n balls are drawn

without replacement from an urn containing r red and b

black balls, the number of possible outcomes is

of which the number favourable to drawing i red and n − i

black balls is

57

7

Probability Theory 7

Hence, the probability of drawing exactly i red balls in

n draws is the ratio

If an urn contains balls of s different colours in the ratios

p

1

: p

2

: . . . : p

s

, where p

1

+⋯+ p

s

= 1 and if n balls are drawn with

replacement, then the probability of obtaining i

1

balls of

the fi rst colour, i

2

balls of the second colour, and so on is

the multinomial probability

The evaluation of equation (3) with pencil and paper

grows increasingly diffi cult with increasing n . It is even more

diffi cult to evaluate related cumulative probabilities—for

example the probability of obtaining “at most j red balls”

in the n draws, which can be expressed as the sum of equa-

tion (3) for i = 0, 1, . . . , j . The problem of approximate

computation of probabilities that are known in principle

is a recurrent theme throughout the history of probability

theory and will be discussed in more detail in the follow-

ing text.

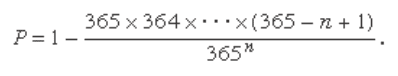

The Birthday Problem

An entertaining example is to determine the probability

that in a randomly selected group of n people at least two

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

58

have the same birthday. If one assumes for simplicity that a

year contains 365 days and that each day is equally likely to

be the birthday of a randomly selected person, then in a

group of n people there are 365

n

possible combinations of

birthdays. The simplest solution is to determine the prob-

ability of no matching birthdays and then subtract this

probability from 1. Thus, for no matches, the fi rst person

may have any of the 365 days for his birthday, the second

any of the remaining 364 days for his birthday, the third any

of the remaining 363 days, . . . , and the n th any of the remain-

ing 365 − n + 1. The number of ways that all n people can have

different birthdays is then 365 × 364 ×⋯× (365 − n + 1), so that

the probability that at least two have the same birthday is

Numerical evaluation shows, rather surprisingly, that

for n = 23 the probability that at least two people have the

same birthday is about 0.5 (half the time). For n = 42 the

probability is about 0.9 (90 percent of the time).

This example illustrates that applications of proba-

bility theory to the physical world are facilitated by

assumptions that are not strictly true, but they should be

approximately true. Thus, the assumptions that a year

has 365 days and that all days are equally likely to be the

birthday of a random individual are false, because one

year in four has 366 days and because birth dates are irreg-

ularly distributed throughout the year. Moreover, if one

attempts to apply this result to an actual group of indi-

viduals, it is necessary to ask what it means for these to be

“randomly selected.” Naturally, it would be unreasonable

to apply it to a group known to contain twins. In spite of

the obvious failure of the assumptions to be literally true,

59

7

Probability Theory 7

as a classroom example, it rarely disappoints instructors

of classes having more than 40 students.

condiTional pRobabiliTy

Suppose two balls are drawn sequentially without replace-

ment from an urn containing r red and b black balls. The

probability of getting a red ball on the fi rst draw is r /( r + b ).

If, however, one is told that a red ball was obtained on the

fi rst draw, then the conditional probability of getting a red

ball on the second draw is ( r − 1)/( r + b − 1), because for the

second draw there are r + b − 1 balls in the urn, of which r − 1

are red. Similarly, if one is told that the fi rst ball drawn is

black, then the conditional probability of getting red on

the second draw is r /( r + b − 1).

In a number of trials the relative frequency with which

B occurs among those trials in which A occurs is just the

frequency of occurrence of A ∩ B divided by the fre-

quency of occurrence of A . This suggests that the

conditional probability of B given A (denoted P ( B | A ))

should be defi ned by

If A denotes a red ball on the fi rst draw and B a red ball

on the second draw in the experiment of the preceding

paragraph, P ( A ) = r /( r + b ) and

which is consistent with the “obvious” answer derived above.