Grace Robert. Advanced Blowout and Well Control

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

216

severe erosion is

certain.

Plusging and bridging are probable in some

areas and

cm

result

in

flow

outside the casing

and

in cratering. Advances

in

diverters

and

diverter system design have improved surface diverting

operations substantially.

Advanced

Blowout

and

Well Control

Special

Conditions, Problems

and

Pmedures in Well

Control

217

References

1.

Grace,

Robert

D., “Further Discussion

of

Application

of

Oil

Muds,” SPE Drilling Engineering, September 1987, page 286.

2.

OBryan,

P.L. and Bourgoyne, A.T., “Methods for Handling

Drilled

Gas

in Oil Muds,” SPE/IADC #16159, SPE/IADC

Drilling Conference held in New

Orleans,

LA, 15-18 March,

1987.

3.

OBryan

P.L. and Bourgoyne,

A.T.,

”Swelling of Oil-based

Drilling Fluids Due to Dissolved

Gas,”

SPE 16676, presented at

the 62nd

Annual

Technical Conference and Exhibition

of

the

Society

of

Petroleum Engineers held in Dallas,

TX,

27-30

September, 1987.

4..

O’Bryan, P.L. et.

al.,

“An

Experimental Study

of

Gas Solubility

in

Oil-base

Drilling

Fluids,”

SPE #15414 presented at the 61st

Annual

Technical

Conference and Exhibition of the Society of

Petroleum Engineers held in New Orleans, LA, 5-8 October,

1986.

5.

Thomas, David C., et.

al.,

“Gas

Solubility in Oil-based Drilling

Fluids: Effects on Kick Detection,” Journal

of Petroleum

Technolom, June 1984, page 959,

CHAPTER

FIVE

FLUID DYNAMICS

IN

WELL CONTROL

The use of kill fluids in well control operations is not new.

However, one of the newest

technical

developments

in

well control is the

engineered application of fluid dynamics. The technology of fluid

dynamics is not fully utilized because most personnel involved in well

control operations do not understand the engineering applications and do

not have the capabilities to apply the technology

at

the rig in the field.

The best well control procedure is the one that has predictable results

from a technical

as

well

as

a mechanical perspective.

Fluid dynamics have an application in virtually every well control

operation. Appropriately applied, fluids can

be

used cleverly to

compensate for unreliable tubulars or inaccessibility. Often, when

blowouts occur, the tubulars are damaged beyond expectation. For

example, at a blowout in Wyoming an intermediate casing string subjected

to excessive pressure was found by survey

to

have filed in

NINE

places.'

One failure is understandable. Two failures are imaginable, but

NINE

failures in one string of casing????? After

a

blowout in South Texas, the

9 Y8-inch surface casing

was

found

to

have parted at

3,200

fect and

again at 1,600

feet.

Combine conditions such

as

just described with the

intense heat resulting

from

an oil-well fire or damage resulting

from

a

falling derrick or collapsing substructure and it is easy

to

convince the

average engineer that after

a

blowout the wellhead and tubulars could be

expected

to

have little integrity. Properly applied, fluid dynamics can

offer solutions which do not challenge the integrity of the tubulars in the

blowout.

The applications of fluid dynamics to

be

considered are:

1.

Kill-Fluid Bullheadmg

2.

Kill-Fluid Lubrication

3.

Dynamic Kill

4.

Momentum Kill

218

FIuidDynamics

in

Well

Control

219

KILL-FLUID

BULLHEADING

“Bullheading” is the pumping of the kill fluid into the well against

any pressure and regardless of any resistance the well may offer. Kill-

fluid bullheading is one of the most common misapplications of fluid

dynamics. Because bullheading challenges the integrity of the wellhead

and tubulars, the result

can

cause firther deterioration

of

the condition of

the blowout. Many times wells have

been

lost, control delayed or options

eliminated by the inappropriate bullheading of kill fluids.

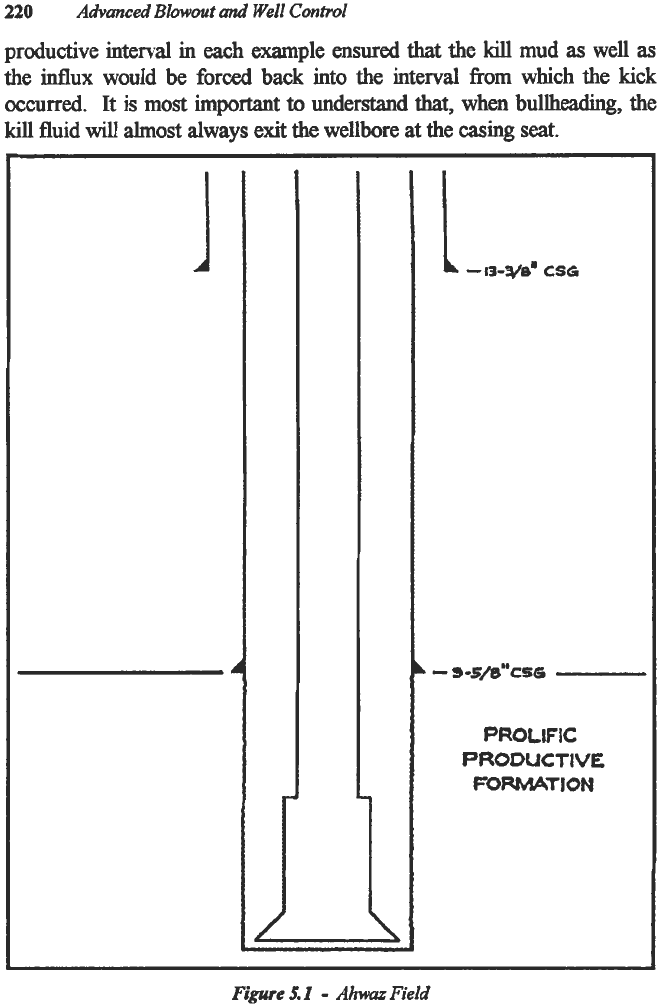

Consider the following for an example

of

a

proper application of

the bullheading technique. During the development of the Ahwaz Field in

Iran in the early 1970s, classic pressure control procedures were not

possible. The producing horizon

in

the Ahwaz Field is

so

prolific that

thc

difference between circulating and loosing circulation is a few psi. The

typical wellbore schematic is presented

as

Figure

5.1.

Drilling in the pay

zone was possible by delicately balancing the hydrostatic with the

formation pore pressure.

The

slightest underbalance resulted in a

significant kick. Any classic attempt

to

control the well

was

unsuccesshl

because even the slightest back pressure at the surface caused

lost

circulation at the 9 5/8-inch casing shoe. Routinely, control was regained

by increasing the weight of two hole volumes of mud

at

the surface by

.1

to

.2

ppg and pumping down the annulus

to

displace the influx and several

hundred barrels of mud into the productive formation. Once the influx

was

displaced, routine drilling operations were resumed.

After the blowout at the Shell Cox in the Piney

Woods

of

Mississippi, a similar procedure was adopted

in

the

deep

Smackover tests.

In

these operations, bringing the formation fluids to the surface was

hazardous due to the high pressures and

high

concentrations of hydrogen

sulfide.

In

response to the challenge, casing was

set

in the top of the

Smackover. When

a

kick was

taken,

the influx was overdisplaced back

into the Smackovcr by bullheading kill-weight mud down the annulus.

The common ingredients of success

in

these two examples are

pressure, casing

seat,

and kick size. The surfice pressures required

to

pump into the formation were low because the kick sizes were always

small. In addition, it was of no consequence that the formation was

fractured

in the process and damaged by the mud pumped.

The

most

important aspect was the casing seat. The casing

that

sat at the top of the

220

productive interval in each example ensured that the

kill

mud

as

well

as

the

influx would be forced back into

the

interval

from

which the kick

occurred.

It

is

most

important

to

understand that, when bullheadmg, the

kill

fluid will almost always exit

the

wellbore at the casing

seat.

Advanced

Blowout

and

Well

Control

PROLIFIC

PRODUCTIVE:

fWRMATION

Figure

5.

I

-

Ahwaz

Field

FluidDynamics

in

Well

Control

221

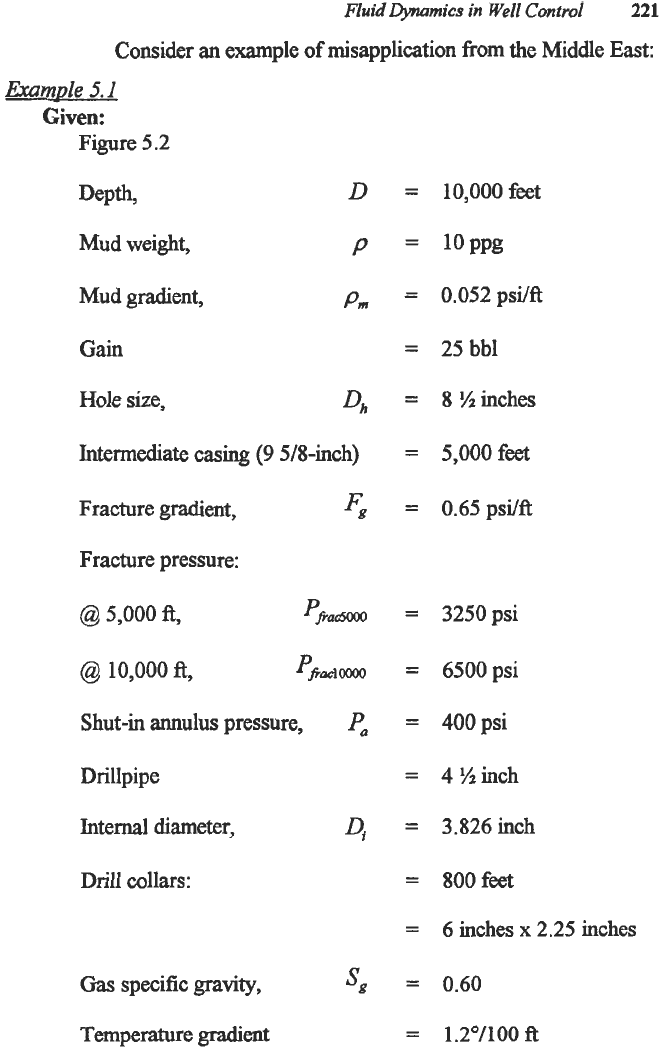

Consider

an

example

of

misapplication

from

the Middle East:

Eramole

5.1

Given:

Figure

5.2

Depth,

D

=

10,OOOfeet

Mud weight,

P

=

1oPPg

Mud gradient,

Pm

=

O.O52psi/f€

Gain

=

25

bbl

Hole size,

D,,

=

8 %inches

Intermediate casing

(9

5/8-inch)

=

5,000

feet

Fracture gradient,

<

=

0.65psiJft

Fracture pressure:

@

5,000

ft,

pfiam

=

3250psi

@

10,000

ft,

~j~odoooo

=

6500psi

Shut-in annulus pressure,

Drillpipe

Internal diameter,

Drill collars:

Gas

specific

gravity,

Temperature

sent

=

4OOpsi

=

4%inch

Dj

=

3.826inch

=

800feet

=

sg

=

0.60

6 inches

x

2.25

inches

=

1.2°/100

ft

222

Advanced

Blowout

and Well Control

Ambient temperature

=

60°F

Compressibility factor,

z

=

1.00

Capacity

of

Drill collar annulus,

cd&

=

0.0352

bbVft

Drillpipe,

Cd*

=

0.0506bbVft

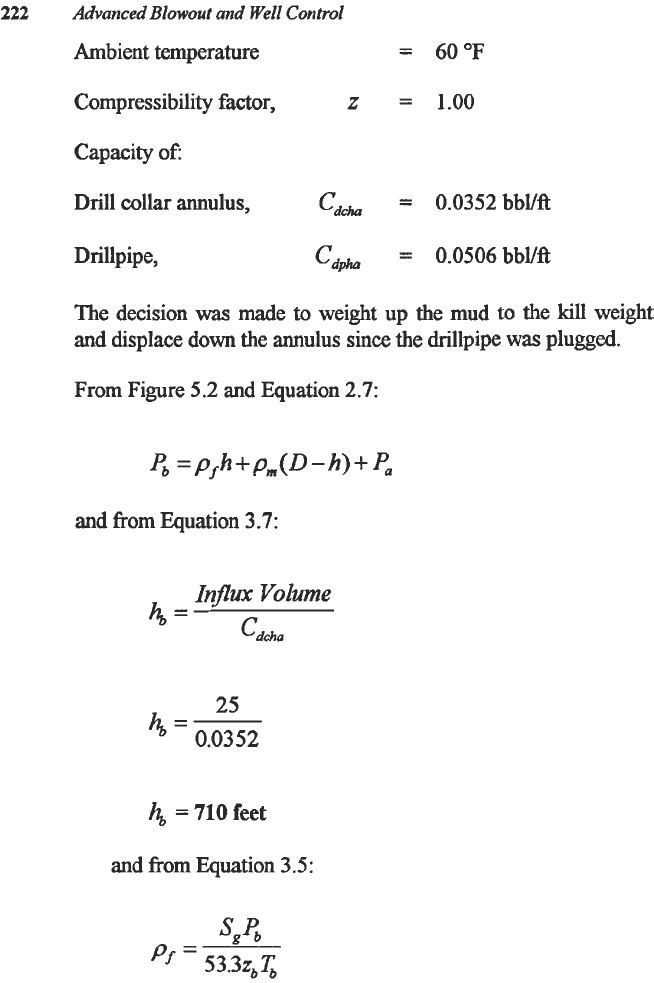

The decision

was

made to weight up the mud to the kill weight

and displace

down

the annulus

since

the drillpipe

was

plugged.

From Figure

5.2

and Equation

2.7:

and from Equation

3.7:

Influx

Volume

‘dcho

hb=

=

710

feet

and fiom Equation

3.5:

Fluid

Wamics

in Well Control

223

FRACTURE

GRADIENT

AT

THE

SHOE

~0.65

PSI/FT

-Pa

~400

PSI

Figure

5.2

I

-

9-5/8"

CSG

AT

5,000

FT.

-

710

FT.

OF

GAS

25

BBI.

GAW

PRODUCTIVE

JNTERVAL

-

T.D.

l0,OOO

FT.

BHP

5,300

PSI

224

Advanced

Blowout

and

Well

Control

Pf

=

53.3(1.0)(640)

(0.6)(5200)

Pf

=

0.091

pdil

Therefore:

pb

=

400+0.52(10000-710)+(0.091)(710)

pb

=

5295

psi

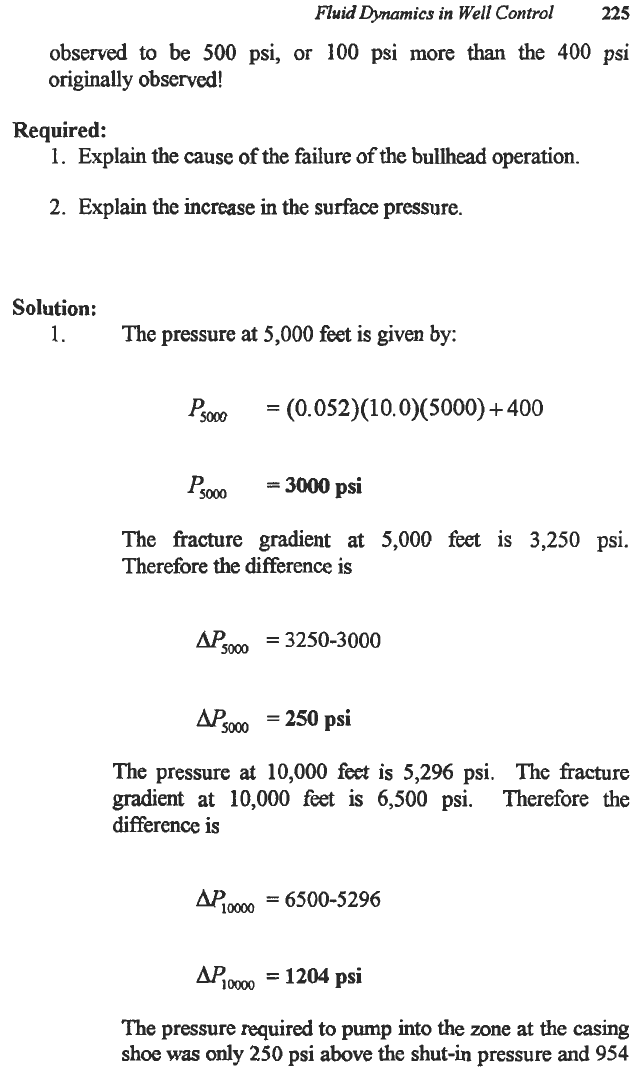

The kill-mud weight would then be given from Equation 2.9:

4

”

=

0.0520

5295

’‘

=

(10000)(0.052)

The annular capacity:

Capcity

=

(9200)(0.0506)

+

(800)(0.0352)

Capacity

=

494

bbls

As

a

result

of

these calculations,

500

barrels

of

mud

was

weighted up

at

the surface to

the

kill

weight

of

10.2 ppg

and

pumped down the annulus. After pumping the

500

barrels

of

10.2ppg

mud,

the well

was-shut

in

and

surface

pressure was

FIuid

Qynamics

in

Well

Control

225

observed to be

500

psi, or 100 psi more

than

the

400

psi

originally observed!

Required:

1. Explain the cause of the failure of the bullhead operation.

2.

Explain the increase in the

surfixe

pressure.

Solution:

1.

The pressure at

5,000

feet

is

given by:

psm

=

(0.052)(10.0)(5000)

+400

psm

=

3000

psi

The fracture gradient at

5,000

feet

is

3,250

psi.

Therefore the difference is

A&,

=

3250-3000

AF&

=25Opsi

The pressure

at

10,000 feet is

5,296

psi. The fracture

went

at

10,000 feet is

6,500

psi. Therefore the

difference is

gm

=

6500-5296

M,oooo

=1204psi

The pressure required to pump into the zone at the

casing

shoe

was

only

250

psi above the shut-in pressure

and

954