Gibilisco S. Teach Yourself Electricity and Electronics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

fixes as multiples for bytes, but when talking or writing about bits per second, these prefixes refer to

powers of 10 rather than powers of 2.

A kilobit per second (1 kbps) is equal to 10

3

= 1000 bps, a megabit per second (1 Mbps) is equal

to 10

6

= 1,000,000 bps, and a gigabit per second (1 Gbps) is equal to 10

9

= 1,000,000,000 bps. (You

won’t often hear of data speed units larger than the gigabit per second.) Hierarchically:

1 kbps = 1000 bps

1 Mbps = 1000 kbps

1 Gbps = 1000 Mbps

Note the lowercase “k” in reference to “kilo-” meaning 10

3

or 1000, and the uppercase “K” in

reference to “kilo-” meaning 2

10

or 1024. Note also that for the other prefix multipliers, uppercase

letters are always used. These are not typos! The “k versus K” distinction is a notational peculiarity,

and is often ignored or overlooked. You will sometimes see “Kbps” rather than “kbps,” or “kB”

rather than “KB,” in technical papers and other documents. As long as you know whether the au-

thor is writing about data speed (bits per second) or memory/storage (bytes), it should not be a

problem. But if you want to be rigorous, this peculiarity is worth remembering.

The Hard Drive

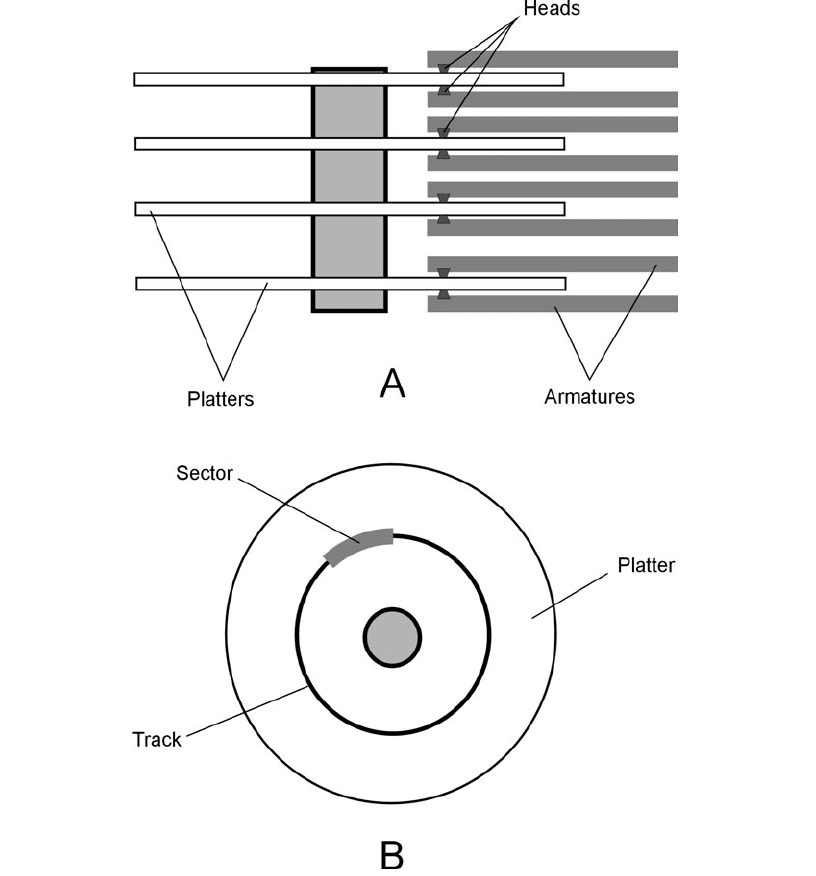

A hard drive, also known as a hard disk, is a common form of mass storage for computer data. The

drive consists of several disks, called platters, arranged in a stack. They are made of rigid, durable ma-

terial that is coated with a ferromagnetic substance similar to that used in audio or video tape. The

platters are spaced a fraction of a centimeter apart. Each has two sides (top and bottom) and two

read/write heads (one for the top and one for the bottom). The assembly is enclosed in a sealed cab-

inet. Figure 33-2A is an edgewise, cutaway view of the platters and heads in a typical hard drive.

Drive Action

When the computer is switched off, the hard-drive mechanism locks the heads in a position away

from the platters. This prevents damage to the heads and platters if the computer is moved. When

the computer is powered up, the platters spin at several thousand revolutions per minute (rpm). The

heads hover a few millionths of a centimeter above and below the platter surfaces.

When you type a command or click on an icon telling the computer to read or write data, the

hard-drive mechanism goes through a series of rapid, complex, and precise movements. The head

positions itself over the particular spot on the platter where the data is located or is to be written;

then the head detects the magnetic fields and translates them into tiny electric currents. All this

takes place in a small fraction of a second.

Data Arrangement and Capacity

The data on a hard drive is arranged in concentric, circular tracks. There are hundreds or even thou-

sands of tracks per radial centimeter of the platter surface. Each circular track is broken into a num-

ber of arcs called sectors. A cylinder is the set of equal-radius tracks on all the platters in the drive.

Tracks and sectors are set up on the hard drive during the initial formatting process. There are also

data units called clusters. These are units consisting of one to several sectors, depending on the

arrangement of data on the platters. Figure 33-2B is a face-on view of a single hard-disk platter,

showing a track and one of its constituent sectors.

The Hard Drive 571

When you buy a computer, whether it is a desktop, notebook (also called laptop), or portable

(also called handheld) unit, it will have a hard drive built in. The drive comes installed and format-

ted. Most new computers are sold with several commonly used programs installed on the hard drive.

Some computer users prefer to buy new computers with only the operating system, by means of

which the programs run, installed; this frees up hard-drive space and gives the user control over

which programs to install (or not to install).

572 A Computer and Internet Primer

33-2 At A, an edgewise view of a hard drive, showing four platters.

At B, a broadside view of a platter, showing one track and one

sector.

External Storage

There are several types of external storage (besides the hard drive) in which data can be kept in large

quantities. Computer experts categorize external storage in two ways: access time and cost per

megabyte (or gigabyte, or terabyte).

Disk Media

Disk media offer the advantage of speed, convenience, and reliability. For personal computers, there

are many forms of external disks. Here are three of the most well-known.

An external hard drive is exactly what its name suggests. This type of device is exceptionally fast,

and has storage capacity similar to the hard drives inside computers. They can be easily connected

to any personal computer with a short cable. Most of these devices require a power supply, often

found in the form of a “brick” that contains a transformer, rectifier, and filter that converts 120 V

ac into the necessary dc for the device.

Compact disk recordable (CD-R) and compact disk rewritable (CD-RW) are popular for backing

up and archiving computer data. You can buy these disks for various other applications, too, such

as storage for digital photos and home videos. They are the same size, physically, as conventional

CD-ROMs, which are used for commercial software, databases, and digital publications. The main

asset of CD-R and CD-RW is moderately large capacity and long shelf life. Most new computers

have built-in drives for these disks.

Diskettes, also called (imprecisely) “floppies,” are about 9 cm (3.5 in) in diameter and enclosed

in a rigid, square case about 4 mm (0.15 in) thick. Their capacity, individually, is limited. They are

all but obsolete. Increasingly, new computers are sold without drives for floppies.

Tape Media

The earliest computers used magnetic tape to store data. This is still done in some systems. You can

get a tape drive for making an emergency backup of the data on your hard drive, or for archiving

data you rarely need to use. Magnetic tape has high storage capacity. There are microcassettes that

can hold more than 1 GB of data; standard cassettes can hold many gigabytes. But tapes are ex-

tremely slow because, unlike their disk-shaped counterparts, they are a serial-access storage medium.

This means that the data bits are written in a string, one after another, along the entire length of the

tape. The drive might have to mechanically rewind or fast-forward through a football field’s length

of tape to get to a particular data bit, whereas on a disk medium, the read/write head never has to

travel farther than the diameter of the disk to reach a given data bit.

Flash Memory

Flash memory is an all-electronic form of storage that is useful especially in high-level graphics, big-

business applications, and scientific work. The capacity is comparable to that of a small hard drive,

but there are no moving parts. Because there are no mechanical components, flash memory is faster

than any other mass-storage scheme, provided it does not cause a software conflict with other pro-

grams in the computer. (Software conflicts can cause a computer to slow down or “freeze up.”)

Flash memory is available in small modules roughly the size of your index finger, and can be

plugged directly into one of the Universal Serial Bus (USB) ports provided in all new computers.

Some flash memory modules come in the form of PC cards (also called PCMCIA cards), which are

credit-card-sized, removable components.

External Storage 573

Memory

In a computer, the term random access memory (RAM), often called simply memory, refers to ICs that

store working data. The amount, and speed, of memory are crucial factors in determining what a

computer can and cannot do.

Data Flow

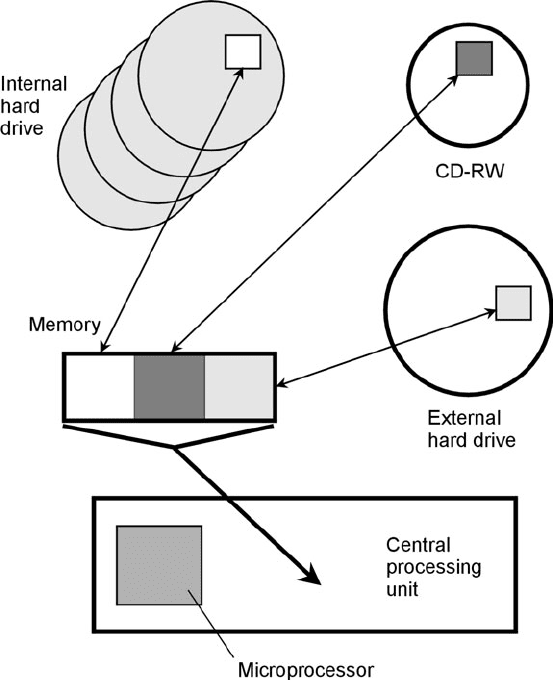

Figure 33-3 shows how data moves in a computer among an internal hard drive, an external hard

drive, and a CD-RW storage medium. This process is controlled by the CPU. When you open a file

on any medium, the data goes immediately into the memory. The CPU, under direction of the mi-

croprocessor, manipulates the data in the memory as you work on the file. Thus, the data in mem-

ory changes from moment to moment.

When you hit a key to add a character, or drag the mouse to draw a line that shows up on your

display, that character or line goes into memory at the same time. If you hit the backspace key to

delete a character, or drag the mouse to erase a line on the screen, it disappears from the memory.

574 A Computer and Internet Primer

33-3 The flow of data

between storage

media and memory

is controlled by

the CPU.

During this time the original file on the storage medium stays as it was before you accessed it. No

change is made to that data until you specifically instruct the computer to overwrite it. When you’re

done working on a file, you tell the microprocessor to close it. Then the data leaves memory and

goes back to the medium from which it came, or to some other place, as you direct. If you tell the

computer to overwrite the file on the medium from which it came, many programs send the new

data (containing the changes you have made) to unused space there; the old data (as it was before

you opened the file) stays in its old location. This is a safeguard, in case you decide to undo the

changes you made.

All the data passing between the storage media and memory, and between the memory and the

CPU, is in machine language. This consists of binary digits (bits) 0 and 1. But the data passing be-

tween you and the CPU is in plain English (or whatever other language you prefer), or in some high-

level programming language, having been translated by the machine into a form you can understand.

Memory Capacity

The maximum number of megabytes or gigabytes of data that can be stored in a computer’s mem-

ory is known as the memory capacity. The main factor that determines memory capacity is the

number of transistors that can be fabricated onto a single memory chip. Other factors, such as mi-

croprocessor speed, have a practical effect on the usable memory capacity.

A gigantic memory is of little practical value if the microprocessor is slow. Nor is a fast micro-

processor worth much if the memory capacity is too small for the applications (programs) you want

to run. Most software packages tell you how much memory you need to run the programs they con-

tain. They’ll often quote two specifications: a minimum memory requirement and a figure for op-

timum performance (approximately twice the minimum requirement). If possible, you should

equip your computer with enough memory for optimum performance.

When buying a new computer, keep in mind that this year’s high-end machine may become

next year’s ordinary one when it comes to popular software, and in a few years it will no longer be

adequate to run many of the programs that will be available. If your computer lacks the memory to

run a given application, you can usually add more. But this can only be done up to a certain point.

Eventually, your microprocessor will no longer be able to run contemporary software at reasonable

speed, no matter how much memory you have.

How much memory do you think your machine will require to run two or three of your favorite

applications at the same time? Double or triple it, and you will come close to the amount you are

likely to need for the next two or three years, or until you are overcome by the urge to buy a new

computer again.

The Display

The visual interface between you and your computer is known as the display. In desktop computers,

an external display is often called a monitor. There are two popular types in use for personal com-

puting today.

A cathode-ray tube (CRT ) monitor resembles a television set without the tuning or volume con-

trols. This type of display is large and heavy, and although some people consider CRTs obsolete,

other computer users prefer them, especially the larger ones, which can have a diagonal screen mea-

sure of 53 cm (21 in) or more.

A liquid crystal display (LCD) is lightweight and thin. This type of display is used in notebook

and portable computers. It has become increasingly popular for desktop computers because the

The Display 575

technology has improved and has become somewhat less expensive than it used to be. Light weight

and a shallow desk profile are decided advantages of this type of display. A good one can provide

image crispness and color at least as good as the best CRT display. An LCD also consumes less

power.

Other types of displays exist. Of special note is the plasma display, which obtains its images

from the properties of electric charges passing through rarefied gases. These displays are often

found in large department stores, where you can see them hanging from the ceilings, displaying

advertisements.

Resolution

The image resolution, often called simply the resolution, of a computer display is one of its most im-

portant specifications. This is the extent to which it can show detail. The better the resolution, the

sharper the image.

Resolution can be specified in terms of dot size or dot pitch. This is the diameter, in millimeters

(mm), of the individual elements in the display—the “smallest unbreakable pieces.” A good display

has a dot pitch that is a small fraction of a millimeter. A typical CRT has a dot pitch of 0.25 or

0.26 mm. The smaller the number, the higher the resolution and, all other factors being equal, the

crisper the image in an absolute sense.

Image resolution can be specified in a general sense as a pair of numbers, representing the num-

ber of pixels (picture elements) the screen shows horizontally and vertically. For a particular screen

size, the greater the number of pixels the unit can display, the crisper the image. In personal com-

puters, typical displays have 800 × 600 resolution (800 pixels wide by 600 pixels high) or 1024 ×

768 resolution. A few can work up to 1600 × 1200 or even higher.

Screen Size

Screen sizes are given in terms of diagonal measure; a popular size is 43 cm (17 in). This will work

quite well at 800 × 600 resolution. For higher resolution, a larger screen is preferable, such as 48 cm

(19 in) or 53 cm (21 in). A high-end display is crucial for doing graphics work, when doing serious

research on the Internet, in remote-control robotics, and in computer gaming. Besides these practi-

cal advantages, a sharp display is more pleasant to work with than a marginal one.

Along with memory and hard-drive capacity, the display is one of the most important parts of

a computer from a user-friendliness standpoint. On the job, long hours at a computer can get te-

dious even if the machine is perfect. An inadequate display can give rise to eye strain and headaches,

and can also degrade the quality and accuracy of work done by people using the computer.

Interlacing and Refresh Rate

Another important consideration in the choice of a display is whether or not it uses interlacing. In-

terlacing increases the obtainable resolution, but it also results in a lower refresh rate (number of

times the entire image is renewed). A low refresh rate can cause noticeable flickering in the image,

and can be especially disruptive in applications where rapid motion must be displayed, such as high-

end computer gaming.

A good refresh rate specification is 70 Hz or more. For applications not involving much mo-

tion, 60 or 66 Hz is adequate for some people, but others complain of eye fatigue because they

can vaguely sense the flicker. Most people find 56-Hz refresh rates too slow for comfort in any

application.

576 A Computer and Internet Primer

ELF Fields

Extremely low frequency (ELF) fields are electromagnetic (EM) fields that fluctuate or alternate more

slowly than conventional radio waves. Such fields are produced by various consumer electronic

devices and appliances. An ELF field is nothing like X rays or gamma rays, which cause radiation

sickness. Nor is ELF radiation like ultraviolet (UV), which can cause skin cancer over long periods.

An ELF field cannot make anything radioactive. In computer systems, the ELF that you’ve heard

about is emitted mainly by electromagnetic CRT monitors. Other parts of a computer system are not

responsible for much ELF energy. The LCDs used in many systems today produce essentially none.

As you learned in Chap. 29, the characters and images in a CRT are created as electron beams

strike a phosphor coating on the inside of the glass. The electrons constantly change direction as

they sweep from left to right, and from top to bottom, on your screen. The sweeping is caused by

deflecting coils that steer the beam across the screen. The coils generate magnetic fields that inter-

act with the negatively charged electrons, forcing them to change direction. Because of the positions

of the coils, and the shapes of the fields surrounding them, there is more magnetic energy radiated

from the sides of an electromagnetic CRT than from the front. If there’s any health hazard with ELF,

therefore, it is greater for someone sitting off to the side of an electromagnetic CRT monitor, and

less for someone watching the screen from directly in front at the same distance.

If you’re concerned about the ELF fields produced by CRT monitors, you might consider buy-

ing an electrostatic CRT unit that has been designed to minimize ELF fields, or buying a stand-

alone LCD display panel. It’s a good idea to arrange your workstation so your eyes are at least 0.5 m

(about 18 in) away from the screen of a CRT monitor, and if you are working near other computer

users, workstations should be at least 1 m (3 ft) apart.

The Printer

There are several types of printer in common use in personal and business computing applications

today. The two most common are the inkjet printer and the laser printer. Less often used are the ther-

mal printer and the dot matrix printer.

Inkjet Printers

In an inkjet printer, tiny nozzles spray ink onto the paper. Most of these printers are comparatively

slow to produce an image, and the ink needs time to dry even after the image comes out, but the

quality can be excellent. Inkjet printers are available in single-color and multicolor designs. The best

color machines produce images of photo quality. In fact, some are designed especially to print digi-

tal photos.

Inkjet printers require periodic replacement of the ink cartridges. These can be quite expensive,

and for this reason, inkjet printers are not well suited for high-volume printing. Inkjet printers re-

quire paper with low fiber content. This keeps the ink from being carried along by capillary action

before it dries, muddling or blurring the printout. Look specifically for “inkjet paper” in computer

supply stores and department stores.

Laser Printers

A laser printer works like a photocopy machine. The main difference is that, while a photocopier

creates a copy of a real image (the paper original), a laser printer makes a copy of a digital computer

image.

The Printer 577

When data arrives at the printer from the computer, the encoded image is stored in the printer

memory. The memory then sends it along to the laser and other devices. The laser blinks rapidly

while it scans a cylindrical drum. The drum has special properties that cause it to attract the print-

ing chemical, called toner, in some places but not others, creating an image pattern that will ulti-

mately appear on the paper. A sheet of paper is pulled past the drum and also past an electrostatic

charger. Toner from the drum is attracted to the paper. The image thus goes onto the paper, although

it has not yet been permanently fused, or bonded, to the paper. The fuser, a hot pair of roller/

squeezers, does this job, completing the printing process.

The main asset of laser printers is their ability to produce a large number of copies at high

speed. They generally have excellent print and graphics quality for grayscale. Color laser printers are

available as well, but they can be quite expensive.

The image resolution of a laser printer ranges from about 300 dots per inch (dpi) for older units

to 1200 dpi, 2400 dpi, or even higher resolutions in state-of-the-art machines. As far as the un-

trained eye can tell, 600 dpi is as good as a photograph. Laser printers can handle graphics and text

equally well. If an image can be rendered on a photocopy machine, it can be rendered just as well

on a laser printer.

Thermal Printers

A thermal printer uses temperature-sensitive dye and/or paper to create hard-copy text and images.

Some thermal printers produce only grayscale images, while others can render full color. Thermal

printers are often preferred by traveling executives who use portable computers, because these print-

ers are physically small and light.

A simple grayscale thermal printer employs special paper that darkens when it gets hot. A color

thermal printer uses thick, heat-sensitive dyes of the primary pigments: magenta (pinkish red), yel-

low, and cyan (bluish green). Sometimes black dye is also used, although it can be obtained by com-

bining large, equal amounts of the primary pigments. The print head uses heat to liquefy the dye,

so it bleeds onto the paper. This is done for each pigment separately.

Some, if not most, thermal printouts fade after awhile. Have you ever pulled out an old store

receipt and found that it was washed-out or blank? Thermal printers can be convenient in a pinch,

but you should be aware that some of them have this problem. If you’re keeping a receipt for tax

purposes or for proof-of-purchase and it has been printed on thermal paper, make a photocopy or a

digital scan of the receipt right away. You can recognize the output of a thermal printer because the

paper curls up when it’s fresh out of the machine.

Dot Matrix Printers

The dot matrix printer is the horse and buggy of the printing family. This type of printer is the least

expensive, in terms of both the purchase price and the long-term operating cost. Dot matrix printers

produce fair text quality for most manuscripts, reports, term papers, and theses. The mechanical parts

are rugged, and maintenance requirements are minimal. Dot matrix printers can render some simple

graphic images, but the quality is fair at best, and it can take a long time to print a single image. Dot

matrix printers cannot reproduce detailed artwork or photographs with acceptable quality.

The Scanner

A scanner is an electromechanical device that converts hard-copy text and graphics into digital form

for processing and storage in a computer.

578 A Computer and Internet Primer

Basic Features

Scanners can save untold hours of tedious manual retyping. Suppose you wrote a book a long time

ago, and have lost the digital files (or used an old-fashioned typewriter, and never had any digital

files!). The hard copy of that book sits in your basement, awaiting the massive editing that can turn

it into a great novel. It needs the power of your computer’s word processor. But you can’t deal with

the prospect of retyping its 1000 pages. A scanner, equipped with optical character recognition

(OCR), can do away with most of the hard labor involved in getting a hard-copy manuscript onto

disk.

A good scanner can be had for a couple of hundred dollars. But the value of optical scanning is

hard to measure. For many entrepreneurs, it can make the difference between staying afloat and

going bankrupt. It can do the work of one or two full-time typists for a tiny fraction of the long-

term cost. Big companies can save money, too. Lawyers and doctors find scanners invaluable for

backing up files of all kinds. Aside from storing text, scanners can make digital copies of vital pa-

pers, records, and receipts, which can be easily backed up on CD-R or CD-RW media.

A typical scanner can render color images, text, photographs, and everything else needed to

make a complete, accurate digital record of any document. Color scanners use three different light

beams (red, blue, and green) to get three different images, which are processed and combined in

much the same way as a color television camera works. The image resolution of a scanner is meas-

ured in dots per inch (dpi), just as is done with printers. The higher the dpi specification, the more

detail the scanner can see.

For reliable scanning of text and most images, a resolution of at least 300 dpi is recommended.

Virtually all scanners meet this requirement. For images, greater detail translates into more memory

consumed. Color increases the amount of memory or storage that an image takes up, if the image

resolution remains constant.

Configurations

Scanners come in three basic configurations. The scanner that’s best for you will depend on what

you want to do with it, and on how much money you’re willing to spend for it.

The cheapest type of scanner is a handheld scanner. It looks something like a miniature vacuum-

cleaner head, or one of the bar-code readers in retail stores. You roll the unit over the paper contain-

ing the text and/or graphics you want to scan. Because the unit is not as wide as most pages, you’ll

have to make two or three passes over the page. Handheld scanners are preferred by people who scan

small images, such as snapshots. They are light in weight, and need almost no desk space. One po-

tential problem is that you might try to scan too fast. Some handheld scanners have speed indicators

that tell you if you’re going too fast. Another potential difficulty is not getting a straight-line scan.

Most handheld units have built-in guides (like miniature rolling pins) that minimize this problem.

If you want to scan a book or magazine, a flatbed scanner is much easier to use than a handheld

scanner. The unit looks something like a photocopier. Using a flatbed scanner is similar to working

a small photocopy machine. You lay the page, photo, or sheet down on a clear glass, and the scan-

ning head moves past it, picking up the image. Flatbed scanners consume desk space, which, if you

have a couple of printers and a fax machine, might already be at a premium.

A sheet scanner, also called a feedthrough scanner, resembles a fax machine (and in fact, many of

these units can do double duty as fax machines). As its name implies, this type of scanner pulls

sheets of paper through, one by one. You can stack several pages, one on top of the other, and the

machine will automatically feed and scan them. However, you can’t scan bound books or magazines

as you can with a flatbed scanner—unless you’re willing to rip out individual pages.

The Scanner 579

Precautions

Even the best scanners make some mistakes when used with OCR. This is especially true if text con-

tains nonstandard symbols. Highly technical material presents the worst problems. Some mathe-

matical symbols are so esoteric that the average person (let alone a machine) is befuddled by them.

Ink spots, stray markings, and smudges on a page can cause scanning errors, in much the same way

as background noise confuses a speech recognition system.

A human reader can often tell what a printed letter should be, even when it is severely muti-

lated. But computers lack human intuition. To some extent this can be corrected by a built-in spell

checker. Some OCR programs have spell checking, but this introduces its own set of problems be-

cause it, too, is imperfect.

If a scanner doesn’t recognize a character, it will usually print a “tag”—a blank space, underline,

or default symbol such as @ or #. Scanned text must always be carefully proofread, and corrections

made with word-processing software, after the data has been stored on the hard drive.

The Modem

The term modem is a contraction of modulator/demodulator. A modem interfaces a computer to a tele-

phone line, digital subscriber line (DSL), cable system, fiber-optic network, wireless network, or radio

transceiver, allowing you to communicate with other computer users and to “surf the Internet.”

Data Speed

Modems work at various speeds, usually measured in kilobits per second (kbps) or megabits per sec-

ond (Mbps). Sometimes you’ll hear about speed units called the baud and kilobaud. (A kilobaud is

1000 baud.) Baud and bits per second are almost the same units, but they are not identical. People

sometimes use the term baud when they really mean bps.

Modem speeds, particularly in cable, fiber-optic, and wireless networks, keep increasing as

computer communications technology advances. Modems are rated according to the highest data

speed they can handle. A typical telephone modem works at about 56 kbps. Modems for more ad-

vanced connections operate much faster.

Slow Modems

A computer works with binary digital signals, which are rapidly fluctuating direct currents. For dig-

ital data to be conveyed over a telephone or radio circuit, the data must be converted to analog form.

In a telephone modem or radio-transceiver modem, this is done by changing the digit 1 into an

audio tone, and the digit 0 into another tone with a different pitch. The result is an extremely fast

back-and-forth alternation between the two tones.

In modulation, digital data from the computer is changed into analog data for transmission over

the telephone line or radio medium. The modulator is therefore a digital-to-analog converter (D/A

converter or DAC). Demodulation changes the analog signals from the telephone line or radio

medium back to digital signals that a computer can understand. The demodulator is thus an analog-

to-digital converter (A/D converter or ADC). The highest practical speed for this type of modem is

approximately 56,000 bits per second (bps), or 56 kilobits per second (kbps).

Amateur radio operators use a variety of digital modes at considerably slower speeds than

56 kbps for Internet-like communications. The principal advantage of amateur radio lies in the fact

that it can work when all else fails. Such communications are not fast, but no infrastructure is

580 A Computer and Internet Primer