Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

182 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

streets lead; for example, “Ishtar, intercessor for her men (people).” Other names promote

morality: “Bow down, proud one!” or “Pray and he will hear you.” Some are simple: “Gemini

Street” and “Narrow Street” (an alternate name for “Bow down, proud one!”).

Private houses follow traditional Mesopotamian types: two or three stories (according to

ancient accounts) with a courtyard in the center. The exceptionally large size of these houses,

and indeed of contemporary examples at Uruk and Ur, shows the prosperity of the region in the

sixth century BC.

The city plan of Babylon differs from the typical Neo-Assyrian urban layout in restoring the

main religious buildings to a place of eminence. The palaces are grandiose, to be sure. But it is

the Temple of Marduk and the ziggurat, not the palace, that occupy the center of the city. The

palaces stand apart, at the edges of the Inner City. In another contrast with Neo-Assyrian prac-

tice, the religious center and the palace areas are not elevated, but are located on the same flat

plane as the rest of the city.

The Processional Way and the Temple of Marduk

Access to the religious center was along a Processional Way that began outside the northern

Ishtar Gate. Images of the gods were carried along this route during the New Year Festival of

Figure 10.12 Plan, Inner city, Babylon

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 183

March or April. The street approached the gate between the high walls of the North Palace

and the bastion opposite, decorated with glazed brick figures of lions, the symbol of Ishtar,

goddess of love and war. The preservation of the Ishtar Gate is curious. Of Nebuchadrezzar’s

third and final version, which was decorated with glazed bricks, little survived above the paved

street. However, the foundations of the gate descended 15m into the ground, buried in clean

sand as befitted sacred buildings, and were decorated with plain (unglazed) brick reliefs depict-

ing dragons and bulls, symbols of the gods Marduk and Adad respectively. It is these walls,

cleared, that the visitor sees today, and that provide the basis for the reconstruction in the

Pergamon Museum in Berlin (Figure 10.13). The original gate would perhaps have measured

Figure 10.13 Ishtar Gate (reconstruction), Babylon

184 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

over 23m in height, and spanned both inner and outer fortification walls. As the Berlin recon-

struction shows, the gate and adjacent walls were well protected with lions, bulls, and dragons

(Figure 10.14) made with colored glazed bricks, sometimes flat, sometimes in relief, set against

a bright blue background.

The Processional Way continued from the Ishtar Gate and the palace southwards over a large

canal toward the Etemenanki, the compound that contained the ziggurat. This ziggurat would

be the Tower of Babel of the Old Testament, but rebuilt many times. Unfortunately, this struc-

ture has survived only in its foundations, ca. 91m square, but it no doubt resembled ziggurats

better preserved elsewhere. According to Herodotus’s description (Bk. I.181–182), it was an

eight-stepped tower with, on top, a temple consisting of a single room furnished with a large

couch where the god Marduk would sleep and, next to the couch, a golden table. Guard duty was

entrusted to a woman.

The street then turned to the west, heading for the Euphrates and the west bank. It passed

between the Etemenanki and the Esagila (or E-sangil), “Temple that raises its Head,” the temple

to Marduk, the principal god of the city. Recovering the plan of the E-sangil posed problems

for the German excavators, because it was buried beneath 21m of later habitation debris and,

in keeping with the religious tradition of this spot, an Islamic shrine. The temple was located by

a lucky hit when Koldewey’s deep test pit struck a paved floor with identifying inscriptions. By

tunneling along its walls workmen recovered its dimensions: 86m × 78m, with two outer courts

to the east. Interior details are few. According to Herodotus, the temple contained a seated

statue of the god, a table, throne, and base, all of gold, but of these precious objects not a trace

remained.

Figure 10.14 Dragon, panel of glazed bricks, Ishtar Gate, Babylon

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 185

The Southern Palace of Nebuchadrezzar

Nebuchadrezzar had three main palaces. The huge Southern Palace was constructed on a raised

platform of baked brick. In plan it resembles the Assyrian type, with public and private rooms

grouped around rectilinear courtyards, here five in number, aligned on an axis. The rectangular

Throne Room, off the largest of the courts, is entered on its long side through three doorways.

This palace, perhaps even this room, we might imagine as the site of both Belshazzar’s feast,

immortalized in the Old Testament Book of Daniel, and, 200 years later, the death of Alexander

the Great.

The exterior wall of the Throne Room was decorated with panels of glazed bricks, with geo-

metric patterns, trees, and animals. In contrast with the Assyrians, the Neo-Babylonians did not

line rooms with stone orthostats or protect entrances with colossal guardian lamassu. Indeed,

apart from the glazed bricks, the ruins of sixth century BC Babylon have yielded little in the way

of arts or crafts. Texts tell us, however, that the rooms were elegantly furnished with fine woods

and trimmed with bronze or gold.

In the extreme north-east of the palace lies a puzzling self-contained cluster of fourteen small

vaulted storerooms surrounded by an unusually thick wall and containing a distinctive well of

three adjacent shafts, seemingly designed for the hauling of water with buckets on a chain. These

rooms may have been the foundations of the celebrated Hanging Gardens, a sort of lavish pent-

house garden. Nebuchadrezzar built these gardens, according to the third century BC historian

Berossus, to satisfy his Median wife’s longing for the forests of her northern homeland. This

achievement so impressed the Greeks that they would include the Hanging Gardens among the

Seven Wonders of the World.

Building the city: the workforce and the money to foot the bill

These many building projects required great manpower. This was supplied in large part by for-

eign labor, skilled and unskilled, brought to Babylon following victorious campaigns. The depor-

tation of peoples was a common occurrence in the Ancient Near East, a method of reducing

the possibility of rebellion. The Hebrews, exiled to Babylonia following the capture of Jerusalem

in 586

BC, were not alone in their plight. But often, after a specific project was completed, such

foreigners were allowed to live in better conditions, owning land and rising in social status.

Also needed for these projects was much money, but this was not so easily found. By the mid-

sixth century BC, the economy of Babylon was under strain, for the conquered territories were

no longer contributing at previous levels. The resulting pressure on the populace may have been

an important element that favored the invading Persians and Cyrus the Great.

THE ACHAEMENID PERSIANS AND PERSEPOLIS

With the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great in 539 BC, the mastery of Mesopotamia passed

to foreigners. And yet the Persians, on the eastern edge of Mesopotamia, were very much in

its cultural sway. Cyrus II the Great (559–530 BC) hailed from Fars, the south-western Iranian

province that gave its name to the state as a whole, Persia. Iran was dominated at this time by

the Medes, centered in the west and north with their capital at Ecbatana, modern Hamadan.

Cyrus’s father, king of Fars, had married a Median princess. In 550

BC, Cyrus defeated Astyages,

the Median king and his grandfather, thereby beginning an extraordinary career of conquest.

His family, the Achaemenid dynasty, achieved mastery of the Near East from the Aegean Sea

186 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

to Central Asia, from the Indus River to Egypt. The dynasty lasted until 330 BC, when it fell to

Alexander the Great.

Like the Neo-Assyrian kings, the Achaemenid Persians founded new capitals to mark the

advent of new monarchs. Pasargadae was the newly created capital of Cyrus the Great. Although

a subsequent ruler, Darius I, would designate the ancient Elamite city of Susa in the Mesopo-

tamian lowlands as his administrative capital, he also established a fortified palatial center at

Persepolis in Fars, the homeland of the dynasty. It is this citadel, Persepolis, that remains the best

known of Achaemenid cities.

Persepolis

Begun early in the reign of Darius I (ruled 521–486 BC) and completed some 100 years later,

Persepolis served as a major center until sacked and burned by Alexander. Extensive excavations

were carried out in the citadel during the 1930s by the Oriental Institute of Chicago under the

direction of Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt. The lower town, home for ordinary people, has

not yet been identified.

The citadel at Persepolis was destined to be a center for both government and ceremoni-

als (Figure 10.15). The palace complex sits on a large platform ca. 455m × 305m. A mud brick

Figure 10.15 Plan, Persepolis

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 187

wall once enclosed most of it, although a low parapet on the west allowed a view across the

plain. Access was through an impressive stairway and a gatehouse, named “All Countries” by its

builder, Xerxes (485–465 BC). Although the palace is divided into public and private sectors with

occasional courtyards, the architecture follows traditions different from those seen in the Iron

Age palaces of Mesopotamia discussed above. Instead of a single integrated whole, the complex

is made up of a cluster of separate buildings on loosely connected individual platforms. The use

of square rooms, large and small, and abundant columns further characterizes the architecture.

The largest of these structures is the Apadana, the great audience hall begun by Darius I, ca.

76m

2

, with a restored height of ca. 20m. Elaborate stone capitals of lions, bulls, or human headed

bulls were used. Balancing the Apadana on the east is another enormous pillared hall, the Throne

Room of Xerxes, also known as the Hall of 100 Columns.

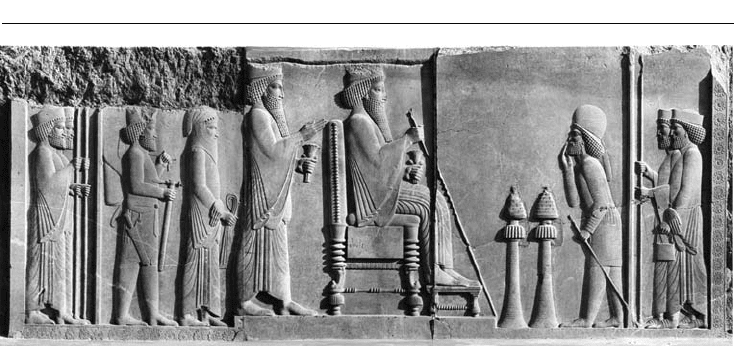

The complex was extensively decorated with relief sculptures that show men from differ-

ent parts of the far-flung empire bringing their tribute to the great king in dignified procession

(Figure 10.16). The king himself appears in a relief from the Treasury, seated on his throne and

approached by a dignitary who presents his homage (Figure 10.17). Behind Darius stand Xerxes,

the crown prince, and officials. The theme of these reliefs is the power and prestige of the Persian

king. Although the idea of using reliefs to convey such a message may well have come from the

Assyrians, the Persians present a different interpretation of royal achievement. Violent triumphs

in battle and hunt are not shown. In further contrast with earlier Mesopotamian art, no god is

present to affirm divine support. Instead, order and obedience characterize the success of this

empire.

Figure 10.16 Apadana, Persepolis: Platform viewed from the north-east

188 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Although Greek sculptors from Ionia (western Anatolia) participated in the carving of these

reliefs, the manner of presentation is traditional Near Eastern. In the relief illustrated here, Dar-

ius and Xerxes are shown in larger scale than the other men, a familiar technique for signaling

high status used as early as the Narmer Palette at the beginning of dynastic Egypt. In addition,

the profile view is standard, and the tribute bearers march in fairly flat relief with little individual-

ity other than ethnic identifiers such as their costume.

Royal tombs

Other buildings in this citadel include private areas or palaces, and a treasury, but cult rooms

are lacking. The Persians were Zoroastrians, worshipping the god Ahuramazda, represented as

a winged sun disk. They held ceremonies at open-air fire altars. Fire altars are depicted in reliefs

on the façades of four royal tombs carved out of the cliffs at Naqsh-i Rustam, 6km north-west

of Persepolis. Four of Cyrus’s successors were buried here. The tombs were robbed in antiquity,

but the decorated façades have survived. The façades are carved in the shape of a cross, with the

entrance to the tomb chamber in the center. The doorway is flanked by two pairs of columns

with bull capitals; they support a couch-like platform held up by two rows of men. On this stands

the king, worshipping at a fire altar, while Ahuramazda hovers overhead.

As for Cyrus the Great, he was buried in a free-standing building at Pasargadae, a simple

single-roomed structure standing on its own stepped platform. The tomb was spared the ravages

of the Macedonian army on the express orders of Alexander the Great, a man well versed in the

history and full of respect for Cyrus. Miraculously it has survived to the present day.

Figure 10.17 Darius receives homage, relief sculpture, from Persepolis

CHAPTER 11

Phoenician and Punic cities

The Phoenicians were the Iron Age successors of the Bronze Age Canaanites, such as the

Ugaritians examined in Chapter 9, continuing earlier cultural traditions without a break. Indeed,

they called themselves Canaanites and their land Canaan. Thus, our modern division between

Bronze Age Canaanities and Iron Age Phoenicians, separated at 1200 BC, is artificial.

Our term “Phoenicia” comes from the Greek “phoinix,” whose meaning is uncertain. One

common explanation derives it from the word for a dark red color, connected with the luxu-

rious purple dye, a Phoenician specialty. A related term, “Punic,” from the Latin words for

Phoenician (poenus, punicus, and poenicus), is used to denote Phoenicians of the central and west

Mediterranean from the sixth to the second centuries BC, the period when Carthage was the

dominant Phoenician city of the region.

The Phoenicians flourished in a small geographical area, the narrow coastal strip of the central

Levant, ca. 200km in length, today the modern Lebanese coast with extensions north into Syria

and south into Israel. This territory was considerably smaller than that of Bronze Age Canaan.

Agriculture was limited by this geography; prosperity came instead from trade. Valuable local

resources included cedar from the mountains of Lebanon, a wood internationally prized for

shipbuilding and architecture, and the murex, a shellfish from which costly purple dye was made.

In addition, the Phoenicians became renowned for making luxury goods. Masters at seafaring,

they set out across the Mediterranean to procure the necessary raw materials, notably metals. This

search took them north to Cilicia and west to Cyprus, North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, and Spain,

Phoenicians: flourished twelfth to fourth centuries BC

Major cities: Tyre, Sidon,

Byblos, Beirut, Arwad

Hiram I, king of Tyre (ruled 969–936

BC)

Assyrian domination: eighth and seventh centuries

BC

Babylonian control: sixth century BC (585–539 BC)

Persian period: 539

BC to 332 BC

Alexander the Great conquers

Phoenicia: 332

BC

Carthage: founded by Tyrians in 814 BC (traditional date)

First treaty with Rome: 509

BC

Defeated at Himera: 480 BC

Punic Wars: 264–146 BC

City captured by the Romans: 146 BC

Refounded by the Romans: 29 BC

190 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

and even to the Atlantic coasts of Morocco and Iberia. Independent in the first centuries of the

Iron Age, the Phoenicians were conquered by the Assyrians in the eighth century BC, and later,

in the sixth century BC, first by the Babylonians and then by the Achaemenid Persians. But their

maritime and commercial skills were important to their conquerors. Despite ongoing conflicts

with their overlords, the Phoenicians remained autonomous, serving as an important cultural

bridge between inland Asia and the Mediterranean world of Greeks, Egyptians, Etruscans, and

the early Romans. Although their own written records have largely disappeared, other cultures

have borne witness to their achievements. The Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet in the

eighth century BC, and the Hebrew Bible attests to the skill of Phoenician craftsmen in the great

building projects of Solomon, king of Israel (see above, Chapter 10).

The Phoenicians, never politically unified, were organized in independent city-states, ruled

by kings. Their cities were located on promontories with a bay, or on small offshore islands – situ-

ations favorable for defense and for shipping. The two main island cities were Tyre and Arwad

(also known by its Greek name, Arados) (Figure 11.1). Major cities situated on mainland promon-

tories were Sidon, Byblos, and Beirut. Despite the historically attested significance of these cities,

the physical characteristics of Phoenician urbanism are elusive. Because of continuing habita-

tion of these sites through Hellenistic and Roman antiquity, then from medieval into modern

times, their appearance from the twelfth to the fourth centuries BC is poorly known. Our under-

standing of Phoenician cities must be assembled from features discovered at a variety of sites

spread throughout the Mediterranean, supplemented by information from ancient documents.

Figure 11.1 Phoenician and related cities in the eastern Mediterranean

TURKEY

Karatepe

SYRIA

IRAQ

JORDAN

S.ARABIA

EGYPT

MEDITERRANEAN SEA

CYPRUS

Arwad

LEBANON

Byblos

Beirut

Sidon

Tyre

Dor

Atlit

ISRAEL

Amathus

Kition

PHOENICIAN AND PUNIC CITIES 191

TYRE

From the mid-tenth to the mid-sixth century BC, Tyre was the most important trading and seafar-

ing city of the Phoenicians. Since contemporaneous Phoenician writings have not survived, we

must piece together its history from such sources as Assyrian annals, which record payments,

tributes, and commercial transactions; the Bible, with accounts of political and trade agreements

and cultural interrelationships; and local authors from later Roman times, such as Josephus (first

century AD) and Philo of Byblos (first and second centuries AD), who consulted earlier chronicles

and archives, now lost.

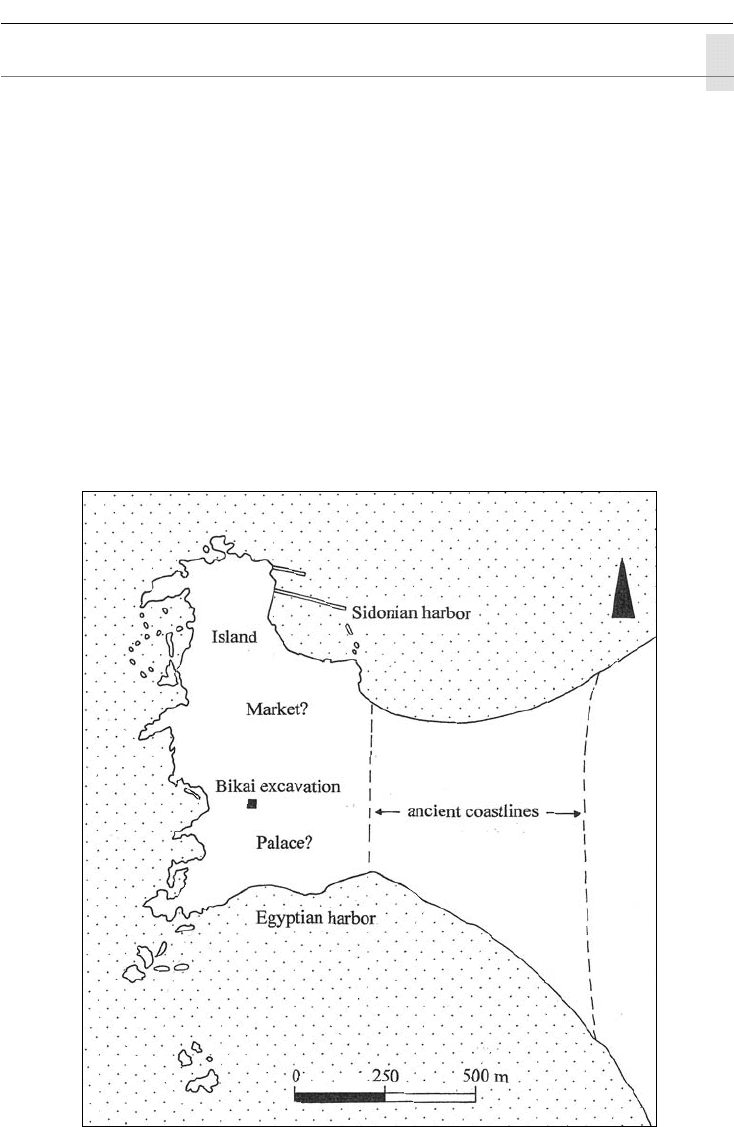

Hiram I, Tyre’s first great king, ruled 969–936 BC. Tradition assigns him an important role in the

city’s development. These details of the appearance of Iron Age Tyre are compiled from literary

sources, for archaeological exploration into this period has been limited (such as Patricia Bikai’s

1974 sounding). Originally the city lay on two adjacent islands just offshore, part of a network of

sandstone reefs and ridges along the Levantine coast. Hiram I joined them, fortified the city, and

supplied it with cisterns (Figure 11.2). The city had two harbors. The “Sidonian” was a natural

harbor on the north, well protected against southwesterly winds, and perhaps enclosed within the

city’s fortification system; it is still used today. A second harbor was added by Ithobaal I (ruled

Figure 11.2 Plan, Tyre