Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

172 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

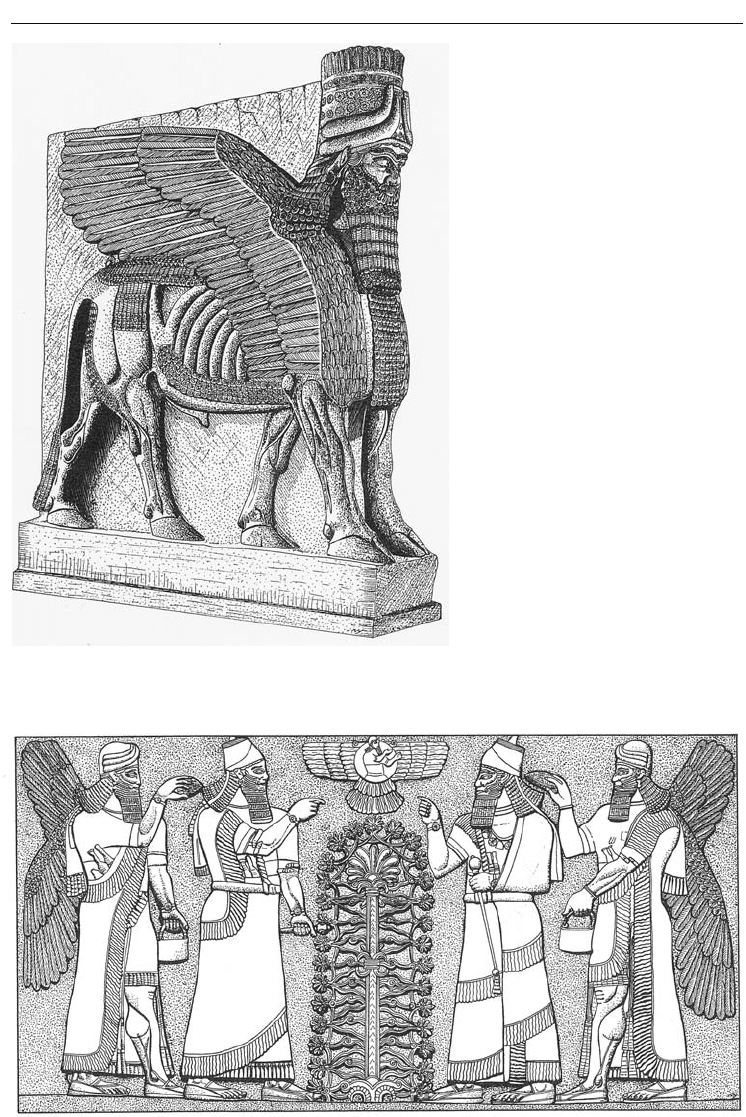

Figure 10.3 Lamassu, from

Khorsabad. Louvre Museum, Paris

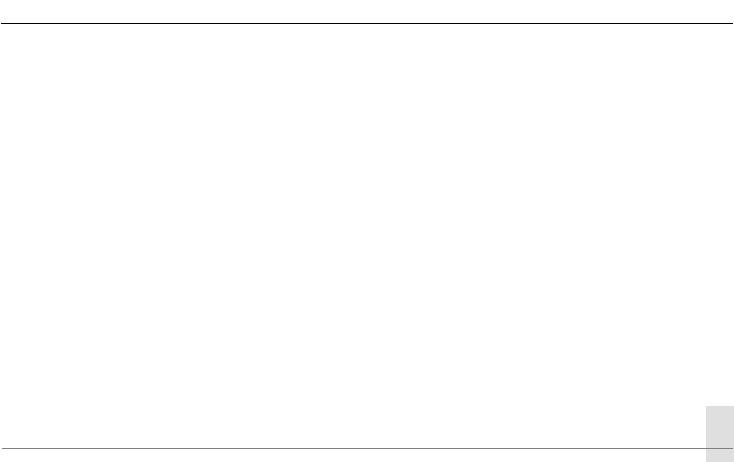

Figure 10.4 Assurnasirpal supplicates the god Assur by a sacred tree, relief sculpture from Kalhu.

British Museum, London

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 173

Since the rooms were cool and dark, the reliefs were originally painted with bright colors

so the subjects could be seen. The written message was important too; bands of cuneiform,

recounting royal deeds, are carved right across the figures. These orthostats served no structural

function, for the palaces were sturdily built of extremely thick mud brick walls, but these depic-

tions of the important aspects of Assyrian kingship surely filled the viewer with appropriate awe

and respect.

In addition to the reliefs, the Northwest Palace has yielded a beautiful series of ivory carvings,

many originally attached to furniture as decorations. Further spectacular finds have come from

excavations conducted in the palace in the late 1980s. Underneath the floor in the residential

quarters Iraqi archaeologist Muzahim Mahmud Hussein uncovered three burial vaults of Assyr-

ian royalty, including the wives of Assurnasirpal II, Tiglath-pileser III (744–727 BC), and Sargon

II, with hundreds of pieces of elaborate gold jewelry draped over the skeletons. When these dis-

coveries are fully published, they will have much to tell us about burial practices and the jeweler’s

craft in Iron Age Assyria.

DUR-SHARRUKIN (KHORSABAD)

Sargon II (721–705 BC) founded his capital at a previously uninhabited location on the Khosr

River, a tributary of the Tigris, 24km to the north of Nineveh. He named his new city Dur-Shar-

rukin, the “Fortress of Sargon,” but today it is generally called Khorsabad, after the modern

village nearby. Like Akhenaten’s Amarna, this town was used only in the lifetime of its builder.

After Sargon was killed in battle, his successors preferred Nineveh. Without royal patronage,

Dur-Sharrukin did not survive.

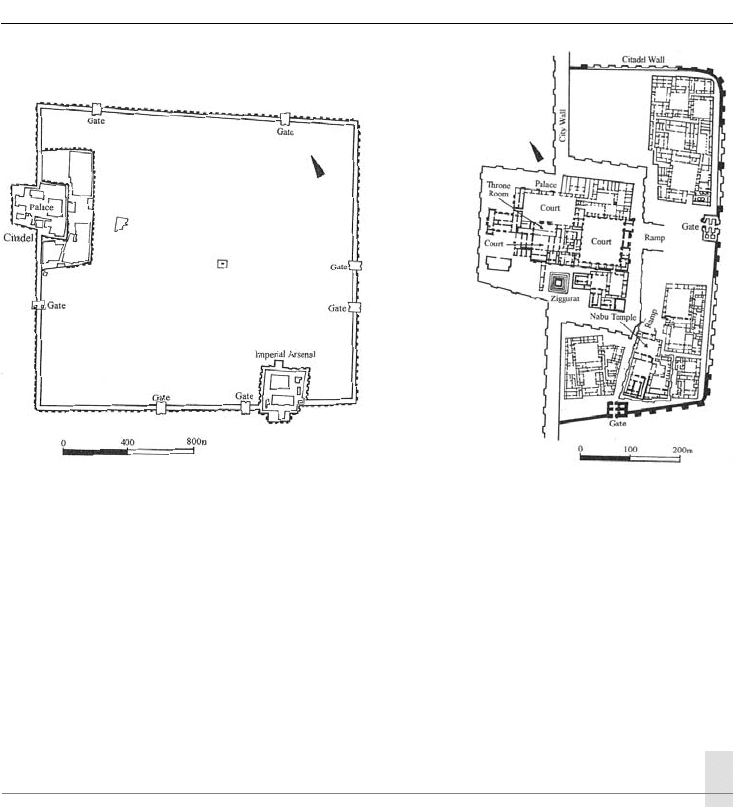

The site has been well explored, from the early efforts of Botta and Place to the expedition

of the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, and the city plan is clear and instructive

(Figure 10.5). Other finds have not fared well: much of the sculpture was sadly lost in 1855 when

brigands in the lower Tigris region attacked and capsized boats transporting some 300 cases of

finds to Basra and Europe.

The city occupied a square-shaped area of nearly 300ha. Its sturdy walls, 20m thick, were of

mud brick on a stone foundation, and studded with towers. Seven gates, placed asymmetrically,

gave access to the city. As at Kalhu and Nineveh, two sectors were set off from the town proper,

protected by a separate set of walls, the Citadel, with the royal palace, in the north-west, and the

Imperial Arsenal in the south.

The palace of Sargon II dominates the citadel (Figure 10.6). It sits elevated on a brick platform

that rises to the height of the city walls, above the ground level of the rest of the citadel. Like the

Northwest Palace at Kalhu, this palace was laid out with a public and a private section. The pub-

lic rooms were grouped around an outer and an inner court. The Throne Room lay off the inner

court, with access given by three doorways. Colossal lamassu guarded the entrance. The interior

was decorated with relief sculpture behind the throne and wall paintings elsewhere; painting was

a cheaper alternative to sculptured slabs. Behind the Throne Room a smaller court served as the

focus of the private quarters of the ruler. Throughout the palace stairs gave access to the flat

roof, held up by long beams of such wood as cedar, cypress, juniper, and maple.

Buildings on the citadel seem to have been placed together in haphazard fashion. The axis

of the palace is not perpendicular to the city walls. This asymmetrical layout is seen also in the

overall palace enclosure and the walls of the citadel. The Nabu Temple, composed of two courts

and enclosed sanctuaries aligned on a separate brick terrace, connected to the palace platform by

174 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

a bridge, is oriented on its own diagonal, and wedged into the southern part of the citadel. For a

complex laid out in a single period this lack of concern for harmony in the placing of buildings

is curious and distinctive.

Few architectural remains have been found in the interior of the city. The excavation team

spent little effort here, to be sure, but it may well be that the city, in its short life, never attracted

much of a population.

NINEVEH

The final capital of the Neo-Assyrians was Nineveh. Sennacherib (704–681 BC), who chose this

old city for new duty, enlarged and refurbished it, and left a detailed account of his good works.

He built a lavish palace, called the “Incomparable Palace,” planted a wonderful park full of

many varieties of herbs and fruit trees, created a reserve for birds and wild animals, and had

stone aqueducts and water channels cut through over 80km of varying terrain to bring water to

the city. But this nature-loving monarch did not shrink from kingly duty. He dealt harshly with

unrest throughout the empire and struck a hard deal with the king of Judah in exchange for spar-

ing Jerusalem. He even sacked and destroyed rebellious Babylon, despite the veneration long

accorded its prestigious gods throughout Mesopotamia. “To quiet the heart of Ashur, my lord,

that peoples should bow in submission before his exalted might, I removed the dust of Babylon

for presents to the (most) distant peoples, and in that Temple of the New Year Festival (in Assur)

I stored up (some) in a covered jar” (Roux 1980: 297).

This time such arrogance did not go unpunished. Sennacherib was murdered by his son or

sons while praying in a temple, “smashed with statues of protective deities” (Roux 1980: 298).

And some seventy-five years later the Babylonians would take their revenge.

Figure 10.5 City plan, Dur-Sharrukin

(Khorsabad)

Figure 10.6 Citadel plan, Dur-

Sharrukin (Khorsabad)

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 175

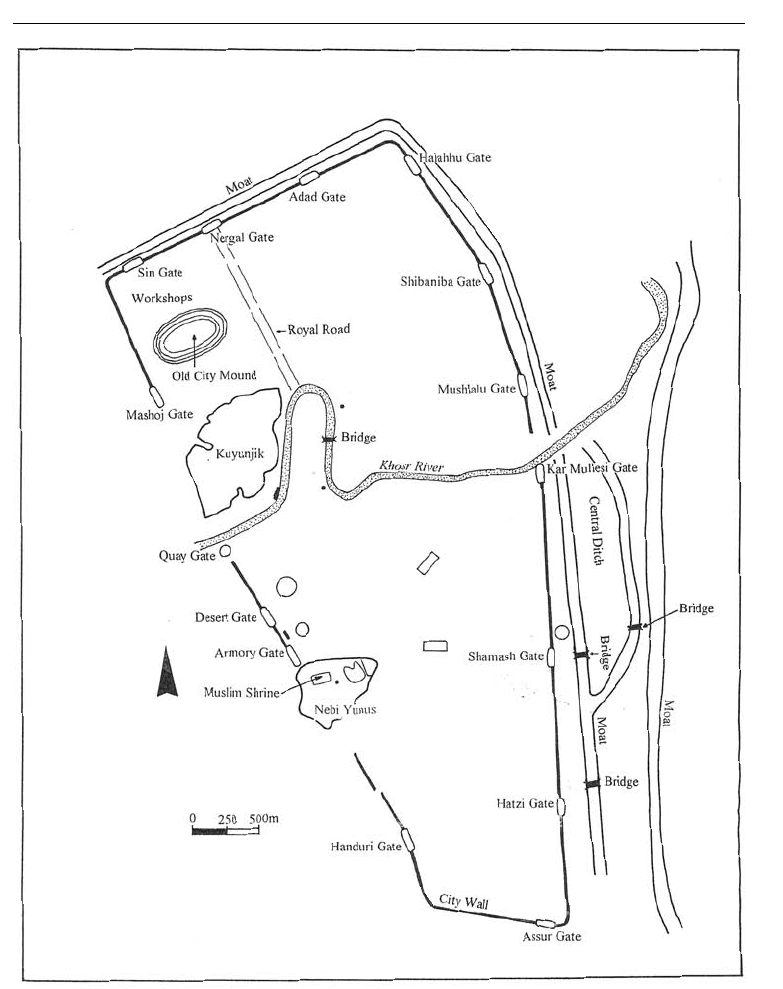

Nineveh occupies a large area on the east bank of the Tigris across from Mosul, in modern

times the largest city of northern Iraq, and has been much explored from the mid-nineteenth

century to the present (Figure 10.7). The walls of the seventh century

BC measure almost 13km in

length, enclosing a huge area of 750ha, the largest city yet known in the Ancient Near East. Only

Babylon would eventually surpass it (see below). Fifteen gateways have been identified. The west

Figure 10.7 City plan, Nineveh

176 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

sector, alongside the river, includes two prominent mounds, a pattern familiar from other Neo-

Assyrian sites: the citadel and the arsenal. The former, here known as Kuyunjik, was investigated

by such nineteenth-century pioneers as Botta, Layard, Place, and Rassam. Here stood the palaces

of Sennacherib and the last of the great kings of Assyria, Assurbanirpal (668–627 BC).

The latter mound, called Nebi Yunus, lies 1km south of Kuyunjik; the two are separated by

the Khosr River, a tributary of the Tigris that divides the ancient city into northern and southern

halves. The Nebi Yunus mound has on it a Muslim shrine associated with Jonah, the prophet

who preached to the Ninevites after he was liberated from the belly of a big fish. Excavations in

and around this religious site have been restricted. Nonetheless, it has been clearly established

that the nerve center of the Assyrian war machine was located here.

Apart from these two major mounds, excavations have been carried out in the north-west

corner of the city, where the “old city mound” was not built upon by the king, but instead served

as an upper-class district. Workshops for ceramics and copper were found nearby. The vast

remaining sections of the city, the Lower Town, were little explored until a surface survey con-

ducted in 1990. The Gulf War of 1991 put a stop to this. But with the city of Mosul expanding

into the south part of the ancient city, the resumption of this important salvage work is urgently

needed.

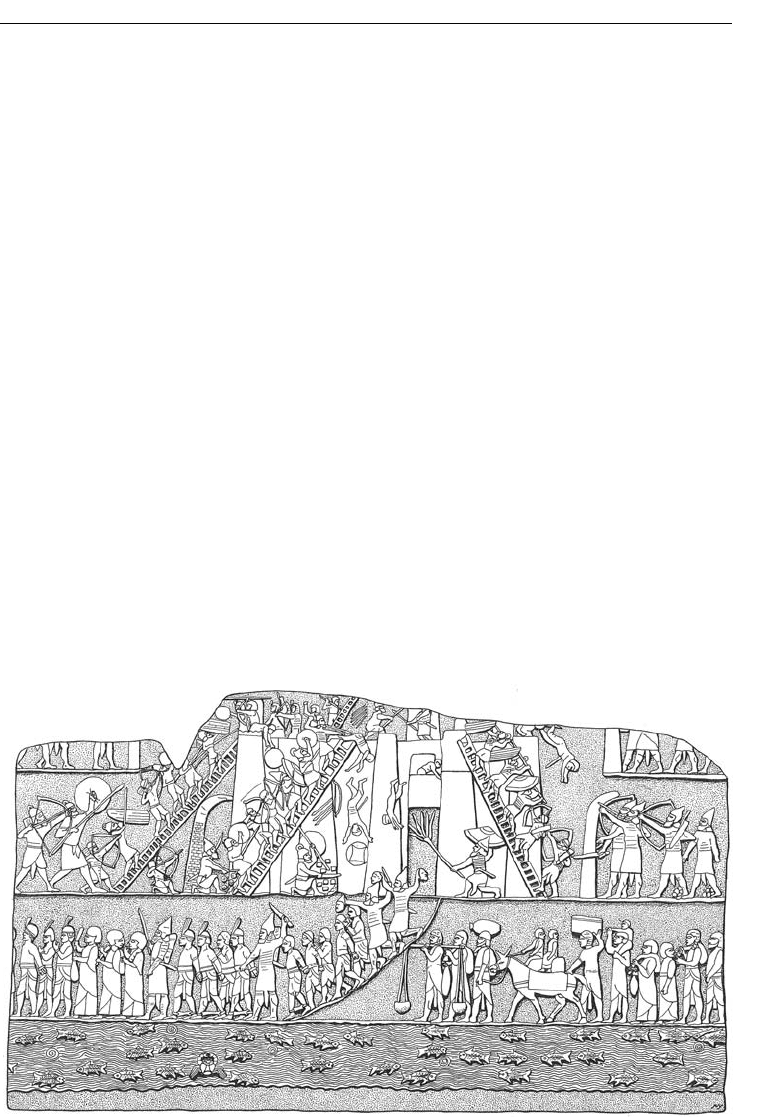

Both royal palaces on the Kuyunjik mound have yielded impressive sculptured slabs. Subjects

conform to those used in the time of Assurnasirpal II, as seen at Kalhu, with the king’s might

illustrated by triumphs in lion hunts and military campaigns (Figure 10.8). Assurbanipal’s first

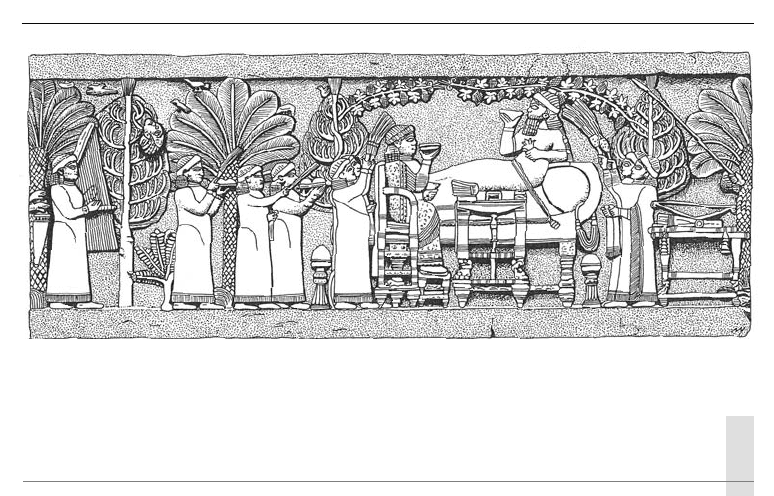

victory over the Elamites is celebrated in a startling relief from his palace at Nineveh (Figure

10.9). The king, reclining on a couch in a pleasant garden, and his queen, seated in a heavy chair,

are fanned by attendants as they drink. To the far left a harpist plays. In the middle of this idyl-

lic scene a head hangs from a tree, the head of Teumman, the Elamite king killed in the Battle

of Til-Tuba. In this matter-of-fact way the fate of enemies and the sangfroid of monarchs were

impressed upon those privileged to see the sculptural decorations of the royal palace.

Figure 10.8 Capture of Ethiopians from an Egyptian city, relief sculpture, from Nineveh. British

Museum, London

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 177

ANATOLIA AND THE LEVANT: PHRYGIAN, URARTIAN,

PHILISTINE, AND HEBREW CITIES

In addition to the Assyrians, many other peoples created cities in the Near East during the Iron

Age. The Phrygians, the Neo-Hittites, and the Urartians in Anatolia, the Phoenicians, the Phi-

listines, and the Hebrews in the Levant, and the Babylonians of southern Mesopotamia all had

important urban centers.

The Phrygians, migrants into Anatolia from the Balkans in the early Iron Age, settled in cen-

tral Anatolia and established their capital at Gordion, now a large höyük west of Ankara. Archaeo-

logical investigations and ancient texts have both contributed to our understanding of their capi-

tal city. Excavations conducted at Gordion since 1950 by the University of Pennsylvania have

revealed impressive urban architecture from the ninth century BC, rebuilt in the eighth century

BC following a catastrophic fire of unknown cause ca. 800 BC. Remains include the massive stone

foundations of the city walls and a district of rectilinear buildings, simple in plan but well-built

and luxuriously furnished, regularly placed side by side along a main street.

Assyrian texts mention a king Mita of Mushki, defeated in battle by Sargon II in south-east

Anatolia in the late eighth century BC. Mita is identified with Midas of Greek legend, the Phrygian

king cursed with the golden touch. The immediate predecessor of Midas, or Mita, may be the

man buried in a log chamber underneath a huge tumulus, an earthen burial mound over 50m

high located a few km from the ancient city center. According to the Greek historian Herodotus,

the Phrygian kingdom and Midas were destroyed in the early seventh century BC by the Kimme-

rians, nomadic invaders from the Caucasus. Excavations have demonstrated that this attack was

just an interruption, not a decisive cultural break. Despite eventual conquest in the sixth century

BC by the Lydians, then by the Persians, Phrygian traditions continued. Much later, in 333 BC,

Alexander the Great, passing through during his campaign against the Persians, would undo

the fabulously intricate Gordion knot with a slice of his sword, an act that foretold his future as

world conqueror.

In North Syria, closer to their heartland, the Assyrians encountered city-states such as Carchem-

ish, capitals of the Neo-Hittite or Aramean kingdoms that were the Iron Age descendants of the

Hittites. To the north lay the Kingdom of Urartu, centered in eastern Anatolia, north-west Iran,

and the Caucasus. The Urartians spoke a language descended from Hurrian, and wrote it in

Figure 10.9 Assurbanipal and his queen, relief sculpture, from Nineveh. British Museum, London

178 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

cuneiform. They owed much of their prosperity to copper and iron mines, and indeed have left

a distinctive repertoire of metal objects. The influence of Assyrian (Mesopotamian) art is great.

In this mountainous area their urban centers such as the Citadel of Van are hilltop fortresses

enclosing palaces and temples, from which the trade routes and the surrounding farms could be

watched and protected.

During the Iron Age, the northern Levant, the coast of modern Lebanon and Syria, was the

heartland of the Phoenicians, the descendants of earlier Canaanites. Because of their important

role in trade and settlement throughout the Mediterranean, their cities will be examined sepa-

rately in the next chapter.

The southern Levant, modern Israel and Jordan, was occupied by several peoples during the

Iron Age, of whom the Philistines and the Hebrews are the best known. The Philistines settled

in the south-west coastal plain, a region eventually known as Philistia, whereas the Hebrews

dominated the hilly interior.

The origins of the Philistines are uncertain. According to one theory, they descended from

the Peleset, one of the components of the Sea Peoples who roamed the eastern Mediterranean

at the end of the Bronze Age. Since they left no written records, the Philistines are known from

archaeological research and from textual evidence left by others, inscriptions in Phoenician and,

notably, the Hebrew Bible. The Bible traces the history of the region from, of course, the Hebrew

point of view; since the Philistines were rivals, the picture is not flattering. The Philistines settled

in five major cities: Ekron (Tell Mikne), Gath (Tell es-Safi), Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Gaza. The first

four, all in Israel, have been explored by archaeologists; ancient Gaza, because of the modern

political situation, is poorly known. Evidence from excavations indicates that different cities

dominated at different times. In the twelfth century BC, Ekron was the largest; later Gath would

be preeminent. Whether the five cities were independent city-states or unified in a single polity is

unknown. In 732 BC, the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III conquered the area. During the centu-

ries that followed, the local culture blended with that of the coastal Canaanites to the north.

Jerusalem and the Hebrew temples

For the Hebrews of the Iron Age, concentrated in the interior, Jerusalem was their major center.

Important Hebrew kings included David (ca. 1000–965 BC) and his son Solomon (ca. 965–931

BC). From David through the next 350 years, Jerusalem was the capital of the Hebrew kingdom

of Judah.

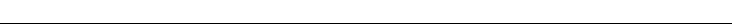

The great Temple, home of the god Yahweh and the Ark of the Covenant, the divinely given

laws, was built under Solomon on a hill (today called “Temple Mount” or, in Arabic, “Haram

esh-Sharif”) just to the north of the earliest settlement of Jerusalem (Figure 10.10). According to

tradition, construction took seven years, and depended heavily on Phoenician artisans and Phoe-

nician materials, such as cedar and cypress (or juniper) wood. This First Temple was destroyed

by the Babylonians in 586 BC, but is thoroughly described in the Bible (I Kings 5–6). It was a

small but lavish rectangular structure measuring 27m × 9m × 13.5m, with three main parts, an

entrance hall, a main room, and an inner sanctuary. The interior was floored with cypress then

covered with gold, the walls paneled with cedar. The sanctuary was lined with gold, as was the

outside of the Temple. Two cherubim, part animal, part human guardians of the sacred, were

suspended in the air to protect the Ark of the Covenant with their outstretched wings. Decora-

tions elsewhere in the Temple included carved cherubim, palm trees, and rosettes, all covered

with gold leaf. Access to the Temple would have been restricted to priests and their attendants.

The people at large worshipped and presented their sacrificial offerings outside.

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 179

The Assyrian threat to Jerusalem in the late eighth and early seventh centuries BC, when Judah

lay on the direct route from Assyria to Egypt, occasioned new fortifications. A remarkable tunnel

ca. 540m long still survives, Hezekiah’s Tunnel, cut to bring water into the city from the Gihon

Spring just outside the city walls during the unsuccessful siege of Sennacherib in 701

BC.

Jerusalem prospered in the seventh century BC, eventually freeing itself from Assyrian domi-

nation. Hebrew independence ended in 586 BC when the Babylonians captured and destroyed

Figure 10.10 Multi-period plan, Old City, Jerusalem

180 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Jerusalem and carried off many of its inhabitants. A reprieve came in 539 BC, when Babylon itself

fell to the Persian king, Cyrus the Great. The exiles returned home, and, with the permission of

Cyrus, the Second Temple was begun. Jerusalem was established once again as the focus of Jewish

culture. The Second Temple would be enlarged and refurbished by Herod the Great in the first

century BC, but destroyed by the Romans in AD 70. The temple has never been rebuilt. The site

is now occupied by important Muslim shrines, the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque.

One key remnant of the Second Temple has survived, however – the Western Wall of the temple

platform. The Wailing Wall, as it is popularly known, is a major site of Jewish veneration.

BABYLON

Babylon, or “Gate of the Gods,” is one of the most celebrated cities in the Ancient Near East.

Like so many Mesopotamian cities, it has a long history. First inhabited in the later Early Dynastic

period, Babylon came to prominence during the reign of Hammurabi in the eighteenth century

BC. The period best documented by archaeological research and textual evidence comes later,

however, in the mid-Iron Age, when Babylon was the monumental capital of a kingdom that

controlled central and southern Mesopotamia. The physical appearance of this seventh to sixth

centuries BC city continues certain long-standing traditions of southern Mesopotamian urban-

ism, but also displays new features. The contrast with the slightly earlier Neo-Assyrian cities of

northern Mesopotamia is especially striking.

Historical background

During the Iron Age, the kingdom of Babylon endured a turbulent relationship with the Assyr-

ians to the north. The city was destroyed by Sennacherib in 689

BC, but much rebuilt by his son

Esarhaddon (ruled 680–669 BC). When the Assyrians fell in 612 BC, the victorious Medes turned

their attentions northward, thus leaving Babylon master of central and southern Mesopotamia.

Under kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadrezzar (the latter ruled 604–562 BC), the Neo-Babylo-

nians restored their cities, with special emphasis on temples; they revitalized trade networks; and

they fought the neighbor states who threatened their prosperity. The capital city, Babylon, was

established as a political, cultural, intellectual, and religious center.

Succeeding rulers proved weak. The curious, fascinating intellectual Nabonidus, who

ascended the throne in 556 BC, had the misfortune of being a contemporary of Cyrus the Great,

the dynamic king of expanding Persia. By 539 BC the Persians, outflanking Babylonia to the north

and east, controlled a vast territory from the Aegean Sea to Afghanistan. When the Persians

attacked Babylon, the Babylonian forces led by Belshazzar, Nabonidus’s son, disintegrated, and

the Persians peacefully occupied the great city. Thus ended the last of the independent states of

ancient Mesopotamia.

The city plan

The Neo-Babylonian city is known from ancient writers Babylonian and Greek, notably the his-

torian Herodotus, and from modern exploration. Major excavations were conducted by German

archaeologist Robert Koldewey from 1899 to 1917. Because of the high water table, Koldewey

could not reach the earlier levels of Hammurabi’s town, so he had to concentrate on the Neo-

Babylonian plan. Apart from the Ishtar Gate, the ancient buildings were not well preserved.

Already by Seleucid (Hellenistic) times baked bricks were being removed for building projects

NEAR EASTERN CITIES IN THE IRON AGE 181

elsewhere. Reconstructions have been undertaken in recent decades, however, as part of excava-

tions conducted by the Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities.

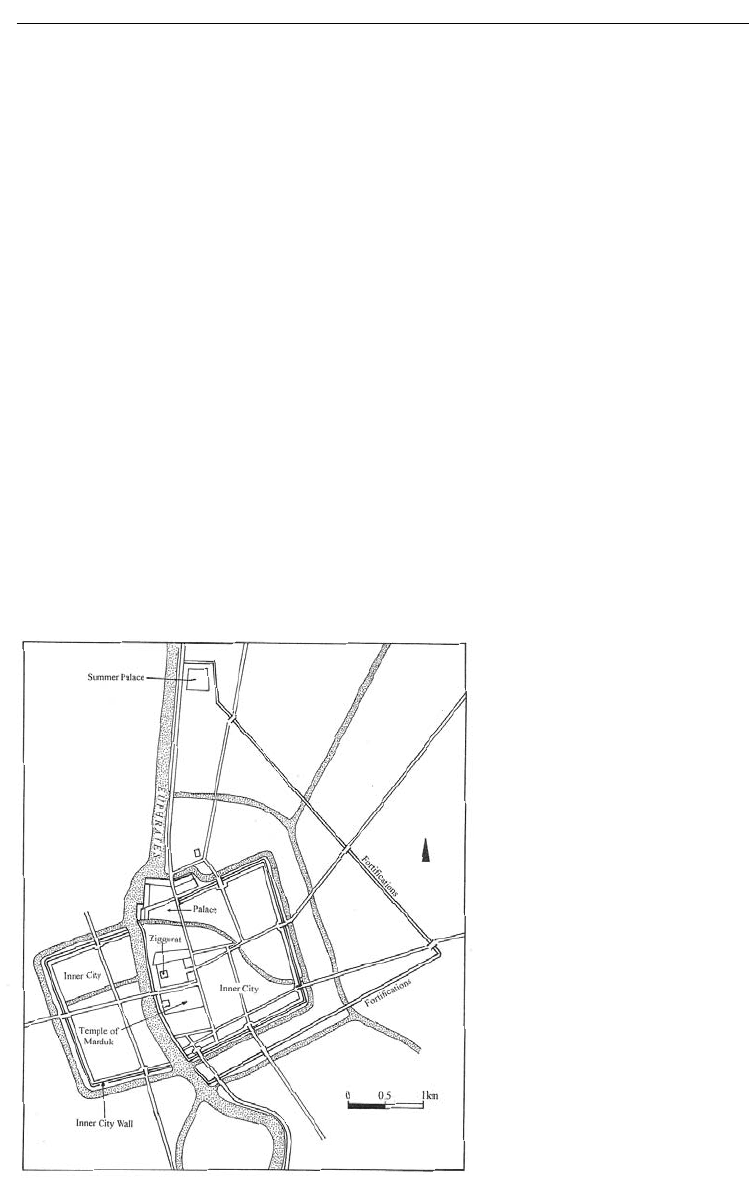

Greater Babylon covered an area of 850ha, the largest city of ancient Mesopotamia, larger

than Nineveh (750ha) and far larger than Ur (60ha). Even the inner city was huge: ca. 400ha. By

using the figure of 200 persons per hectare, a standard benchmark for determining urban popu-

lations in central and southern Mesopotamia, we can estimate the population of the inner city

at 80,000. The city comprised two fortified sections, one inside the other, with the Euphrates,

flowing north–south through the city, an important element of this defensive system (Figure

10.11). The outermost fortifications were laid out as a huge triangle, of which one side was the

Euphrates itself. The other two legs stretching to the east consisted of a triple line of walls and a

moat. Inside this triangle lay a rectangular core, the inner city, separately fortified. One compo-

nent of this was the city center, site of the major monuments of the city: the royal palace, the cult

centers, and the old residential quarter (Figure 10.12).

The rectangular core of Babylon began as a fortified square on the east bank of the Euphrates

River. The area was expanded to the west bank by Nebuchadrezzar, making a total area of ca.

1.6km × 2.4km. The fortification consisted of a double line of mud brick walls, the inner measur-

ing 6.5m in thickness, the outer 3.7m. The unfilled space between them served as a roadway. A

moat was cut in front of the exterior of the walls and linked to the Euphrates, with iron gratings

protecting against intruders. Baked brick set in the sealant bitumen reinforced walls in contact

with the water. Bridges gave access to the eight gates into the city.

The city was laid out in a grid, with straight streets oriented toward the river. Such a regular

layout was unusual for a central or southern Mesopotamian city. The names of several streets

are known, listed on tablets together with the neighborhoods, the many cult places, and other

topographical features. The street names are striking. Some honor the gods to whose gates the

Figure 10.11 Overall city plan,

Babylon