Furusawa A., van Loock P. Quantum Teleportation and Entanglement: A Hybrid Approach to Optical Quantum Information Processing

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

80 2 Introduction to Optical Quantum Information Processing

versions of the CV qumode stabilizer states, as they were introduced in the preced-

ing chapter.

Sections 2.3 and 2.4 are devoted to general quantum optical unitaries and the

special case of Gaussian unitary transformations, respectively. Similarly, in Sec-

tions 2.5 and 2.6, respectively, we shall discuss non-unitary maps within a general

quantum optical framework and in the Gaussian regime, including the important

Gaussian channels. Finally, we conclude this chapter with a few remarks on the

possibilities of linear optical schemes for quantum information (Section 2.7) and

general optical approaches to quantum computation (Section 2.8).

2.1

Why Optics?

For communication, it is obvious that light is the ideal carrier of information at a

maximum speed for any signal transfer. However, is there also an advantage of us-

ing light for computation? Before talking about quantum information processing,

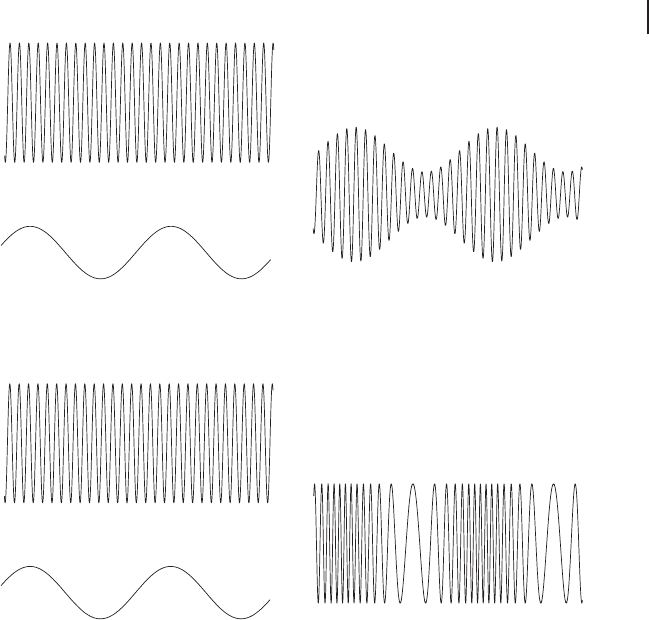

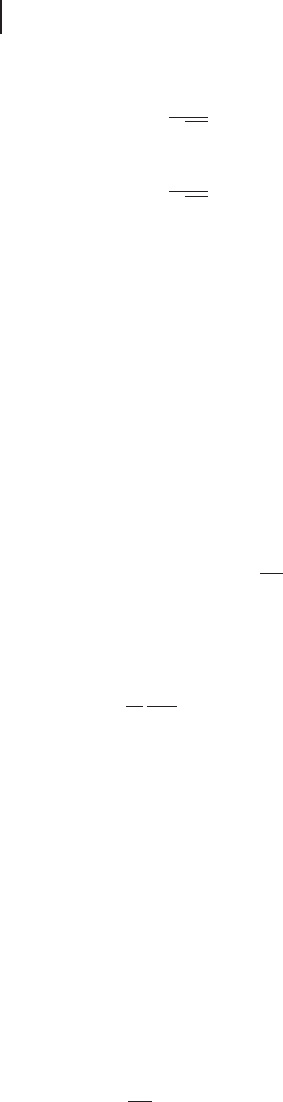

let us start with ordinary electronics. As a typical example, consider AM and FM

radio. It is well-known that a signal is encoded as amplitude modulation of a carri-

er wave in AM radio, as shown in Figure 2.1. Similarly, in FM radio, the signal is

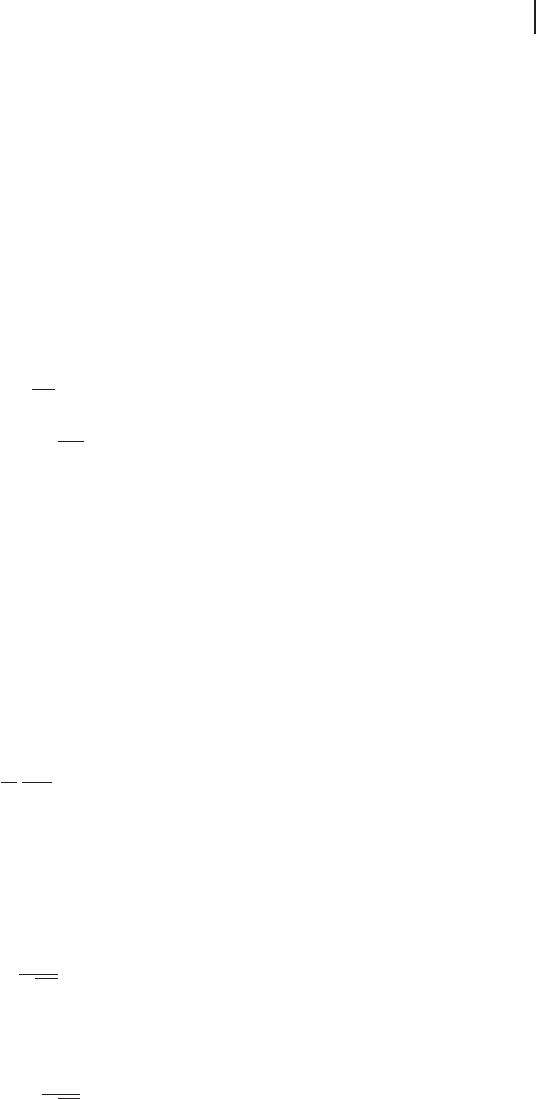

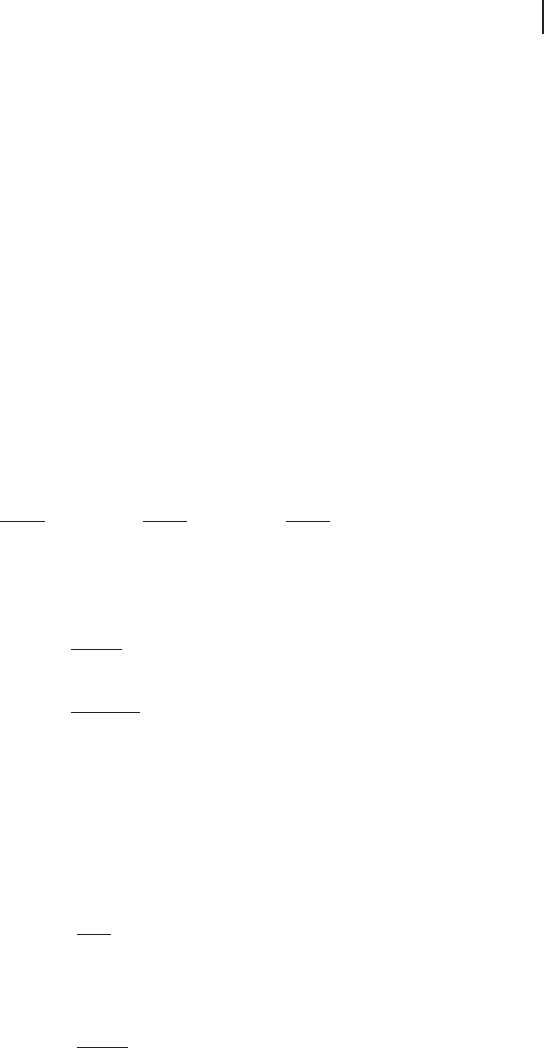

encoded as frequency (phase) modul ation of a carrier wave, as shown in Figure 2.2.

We can then extract or demodulate the encoded signal through homodyning.

This means essentially multiplication between the received modulated wave and

an output of a local oscillator with the same frequency as the carrier wave at the

receiver. More precisely, when the received wave is A(t)sinωt (A(t): amplitude

modulation, AM signal, ω: carrier-wave frequency) and the local oscillator output

is B sin ωt,weobtain

A(t)sinω t B sin ωt D A(t)B

1 cos 2ωt

2

, (2.1)

after the mixing (multiplication) with a mixing circuit. This signal then passes

through a low-pass filter, and we get A(t)B/2 for the homodyne output. By means

of this homodyning, we can tune the frequency (channel) and have the gain B by

using the local oscillator. Similarly, we can demodulate the FM signal by changing

the local oscillator phase.

The regime discussed here is classical because the frequencies of the carrier

waves of AM and FM radio are at most 100 MHz and so we can neglect the photon

energy hν, which is much smaller than the thermal energy k

B

T . However, the

situation totally changes for optical frequencies. These are around 100 THz and

the photon energy h ν is much higher than the thermal energy k

B

T .

Therefore, in the regime of optical frequencies, we can no longer neglect the

occurrence of photons in a quantum mechanical description. In particular, there

will be an uncertainty relation between the AM and FM signals of the carrier light

and as a result, we cannot determine the AM and FM signals of the carrier light simul-

taneously. Here, in the quantum mechanical description, the AM and FM signals

2.1 Why Optics? 81

Carrier wave

Modulation signal (AM)

Maximum amplitude

Minimum amplitude

Amplitude-modulated carrier wave

Figure 2.1 Amplitude modulation for AM radio.

Carrier wave

Modulation signal (FM)

Maximum frequency

Minimum frequency

Frequency-modulated carrier wave

Figure 2.2 Frequency (phase) modulation for FM radio.

would correspond to the quadrature components Ox and Op defined for a qumode

(see Sections 1.2 and 2.2).

We can now perform homodyne detection for optical frequencies. In this case,

the laser corresponds to a local oscillator and the beam splitter corresponds to

a mixing circuit for optical frequencies. We may then demodulate the A M and

FM signals of the carrier light through homodyne detection by changing the

phase of the optical local-oscillator beam. Eventually, in this type of measurement,

quantum mechanics and the presence of photons becomes manifest as a shot

noise.

Although the shot noise or quantum fluctuations of the AM and FM signals is

inevitable, the signals can become correlated on a nonclassical level for the multi-

beam case. Fo r example, with two optical beams A and B, it is possible to have

Ox

A

Ox

B

! 0,

Op

A

COp

B

! 0, (2.2)

82 2 Introduction to Optical Quantum Information Processing

where Ox

A

and Ox

B

are the AM signals for the optical beams A and B, while Op

A

and

Op

B

are the corresponding FM signals. Most importantly, Ox

A

and Op

A

cannot simulta-

neously t ake on certain values according to the uncertainty relation, and the same

applies to Ox

B

and Op

B

. However, for combinations of the AM and FM signals, si-

multaneous values such as zero i n Eq. (2.2) are possible because the uncertainty

relation only prohibits the occurrence of a simultaneous eigenstate of two non-

commuting observables of one optical beam, but not for two commuting observ-

ables of two optical beams. This type of nonclassical correlation is a manifestation

of entanglement (see Chapter 3).

To conclude this section, we state that optics is a natural extension of electronics

from the classical to the quantum domain and therefore well suited for quantum

information processing.

2.2

Quantum Optical States and Encodings

The distinct quantum features of light have been known much longer than the rel-

atively new ideas of quantum information theory. The famous papers by Glauber

from 1963 [106–108] based on a rigorous quantum formulation of optical coher-

ence represent milestones of a quantum theory of light. Thanks to the invention

of the laser, a lot of progress has been made in experimental quantum optics as

well.

What are the consequences of a quantum description of light? Put in simple

terms, not only must the position and momentum of massive particles such as

electrons obey the Heisenberg uncertainty relation, but also electromagnetic field

observables such as the “quadrature amplitudes”. In its simplest form, this be-

comes manifest in an uncertainty relation for a single qumode, as expressed by

Eq. (1.43). Effectively, the quantized field represents a collection of quantum os-

cillators, that is, in our terminology, a collection of qumodes. As a consequence,

light fields emitted from a laser source not only exhibit thermal fluctuations that

in principle might be entirely suppressed, but also intrinsic unavoidable quantum

fluctuations. The quantum state of the electromagnetic field closest to a well de-

termined classical state is the so-called coherent state, with minimum uncertainty

symmetrically distributed in phase space. Any decrease of, for example, the ampli-

tude uncertainty (“amplitude squeezing”) must be accompanied by an increase of

the phase uncertainty (“phase antisqueezing”) because otherwise the Heisenberg

uncertainty relation is violated.

Originally, squeezing was considered as a means to enhance the sensitivity of

optical measurements near the standard quantum limit (for example, in the inter-

ferometric detection of gravitational radiation [109] or for low-noise communica-

tions [110]). Later, we shall see that squeezed light represents a readily available

resource to produce entanglement (Chapter 3). Let us now start by describing the

quantization of the free electromagnetic field.

2.2 Quantum Optical States and Encodings 83

2.2.1

Field Quantization

In quantum optics textbooks, the electromagnetic field is usually quantized with-

out a rigorous quantum field theoretical approach based on a more heuristic sub-

stitution of operators for c numbers. This approach is sufficient to identify modes

of the electromagnetic field as quantum mechanical harmonic oscil lators. It ulti-

mately reveals that the number of photons in a mode corresponds to the degree of

excitation of a quantum oscillator. Thus, in this sense, photons have a much more

abstract and mathematical meaning than the “light particles” that Einstein’s 1905

papers referred to for interpreting the photoelectric effect.

The starting point now shall be the Maxwell equations of classical electrodynam-

ics,

rE D

@B

@t

, (2.3)

rH D j C

@D

@t

, (2.4)

rD D , (2.5)

rB D 0, (2.6)

with D D ε

0

E C P and B D µ

0

H C M. Here, ε

0

is the electric permittivity of free

space and µ

0

is the magnetic permeability (with ε

0

µ

0

D c

2

, c the vacuum speed

of light). Considering the free electromagnetic field allows us to remove all charges

and currents ( D 0, j D 0), and also any electric polarization an d magnetization

(P D 0, M D 0).

By inserting Eq. (2.4) with H D B/µ

0

into Eq. (2.3), with D D ε

0

E,andwith

rrE Dr(rE) r

2

E and E q. (2.5), one obtains the wave equation for the

electric field

r

2

E

1

c

2

@

2

E

@t

2

D 0, (2.7)

and likewise for the magnetic field.

In his quantum treatment of optical coherence, Glauber regarded the electric and

magnetic field as a pair of Hermitian operators,

O

E(r, t)and

O

B(r, t), both obeying

the wave equation [107]. Written as a Fourier integral, Hermiticity of the electric

field operator,

O

E(r, t) D

1

p

2π

1

Z

1

dω

O

E(r, ω)e

iω t

, (2.8)

is ensured through

O

E (r, ω) D

O

E

†

(r, ω). The positive-frequency part,

O

E

(C)

(r, t) D

1

p

2π

1

Z

0

dω

O

E (r, ω)e

iω t

, (2.9)

84 2 Introduction to Optical Quantum Information Processing

and the negative-frequency part,

O

E

()

(r, t) D

1

p

2π

0

Z

1

dω

O

E (r, ω)e

iω t

D

1

p

2π

1

Z

0

dω

O

E

†

(r, ω)e

Ciω t

, (2.10)

regarded separately, are non-Hermitian operators with

O

E(r, t) D

O

E

(C)

(r, t) C

O

E

()

(r, t). They are mutually adjoint, that is,

O

E

()

(r, t) D

O

E

(C)†

(r, t). In fact,

Glauber realized that

O

E

()

(r, t)and

O

E

(C)

(r, t) must represent photon creation and

annihilation operators, respectively [107].

However, we will find it more convenient to describe the electromagnetic field by

a discrete set of “mode variables” rather than the whole continuum of frequencies.

We will now deal with this discretization according to Walls and Milburn [29] whose

approach is based on Glauber [108].

2.2.1.1 Discrete Modes

The free electromagnetic field vectors may both be determined from a vector po-

tential A(r, t)as

B DrA , E D

@A

@t

, (2.11)

wherewehavetakentheCoulombgaugeconditionrA D 0. Using these equa-

tions for the vector potential and the free Maxwell equations, we can also derive the

wave equation for A(r, t),

r

2

A

1

c

2

@

2

A

@t

2

D 0 . (2.12)

The vector potential can also be written as A(r, t) D A

(C)

(r, t) C A

()

(r, t), where

again A

(C)

(r, t) contains all amplitudes which vary as e

iω t

for ω > 0andA

()

(r, t)

contains all amplitudes which vary as e

Ciω t

[the positive and negative frequency

parts here are still c numbers, A

()

D (A

(C)

)

]. In order to discretize the field

variables, we assume that the field is confined within a spatial volume of finite size.

Now, we can expand the vector potential in terms of a discrete set of orthogonal

mode functions,

A

(C)

(r, t) D

X

k

c

k

u

k

(r)e

iω

k

t

. (2.13)

The Fourier coefficients c

k

are constant because the field is free. If the volume con-

tains no refracting materials, every vector mode function u

k

(r) corresponding to

the frequency ω

k

satisfies the wave equation [as the mode functions must inde-

pendently satisfy Eq. (2.12)]

r

2

C

ω

2

k

c

2

!

u

k

(r) D 0 . (2.14)

2.2 Quantum Optical States and Encodings 85

More generally, the mode functions are required to obey the transversality condi-

tion,

ru

k

(r) D 0 , (2.15)

and they shall form a complete orthonormal set,

Z

u

k

(r)u

k

0

(r)d

3

r D δ

kk

0

. (2.16)

The plane wave mode functions appropriate to a cubical volume of side L may now

be written as

u

k

(r) D L

3/2

e

(λ)

e

ikr

, (2.17)

with e

(λ)

being a unit polarization vector [perpendicular to k due to transversality

Eq. (2.15)]. We can verify that this choice leads with the wave equation (Eq. (2.14)) to

the correct linear dispersion relation jkjDω

k

/c.Thepolarizationindex(λ D 1, 2)

and the three components of the wave vector k are all labeled by the mode index

k. The permissible values of the components of k are determined in a familiar way

by means of periodic boundary conditions,

k

x

D

2π n

x

L

, k

y

D

2π n

y

L

, k

z

D

2π n

z

L

,

n

x

, n

y

, n

z

D 0, ˙1, ˙2, . . . (2.18)

The vector potential then takes the quantized form [29, 108, 111]

O

A(r, t) D

X

k

„

2ω

k

ε

0

1/2

h

Oa

k

u

k

(r)e

iω

k

t

COa

†

k

u

k

(r)e

Ciω

k

t

i

D

X

k

„

2ω

k

ε

0

L

3

1/2

e

(λ)

h

Oa

k

e

i(krω

k

t)

COa

†

k

e

i(krω

k

t)

i

, (2.19)

where now the Fourier amplitudes c

k

from Eq. (2.13) (complex numbers in the clas-

sical theory) are replaced by the operators Oa

k

times a normalization factor. Quan-

tization of the electromagnetic field is accomplished by choosing Oa

k

and Oa

†

k

to be

mutually adjoint operators. The normalization factor renders the pair of operators

Oa

k

and Oa

†

k

dimensionless. According to Eq. (2.11), the electric field operator be-

comes

O

E(r, t) D i

X

k

„ω

k

2ε

0

1/2

h

Oa

k

u

k

(r)e

iω

k

t

Oa

†

k

u

k

(r)e

Ciω

k

t

i

, (2.20)

and, likewise, the magnetic field operator,

O

B(r, t) D i

X

k

„

2ω

k

ε

0

1/2

h

Oa

k

k u

k

(r)e

iω

k

t

Oa

†

k

k u

k

(r)e

Ciω

k

t

i

.

(2.21)

86 2 Introduction to Optical Quantum Information Processing

Inserting these field operators into the Hamiltonian of the electromagnetic field,

O

H D

1

2

Z

ε

0

O

E

2

C µ

1

0

O

B

2

d

3

r , (2.22)

using Eqs. (2.15) and (2.16), the Hamiltonian may be reduced to

O

H D

1

2

X

k

„ω

k

Oa

†

k

Oa

k

COa

k

Oa

†

k

. (2.23)

With the appropriate commutation relations for the operators Oa

k

and Oa

†

k

,theboson-

ic commutation relations

[

Oa

k

, Oa

k

0

]

D

h

Oa

†

k

, Oa

†

k

0

i

D 0,

h

Oa

k

, Oa

†

k

0

i

D δ

kk

0

, (2.24)

we recognize the Hamiltonian of an ensemble of independent quantum harmonic

oscillators,

O

H D

X

k

„ω

k

Oa

†

k

Oa

k

C

1

2

. (2.25)

The entire electromagnetic field therefore may be described by the tensor product

state of all these quantum harmonic oscillators of which each represents a single

electromagnetic mode. The operator Oa

†

k

Oa

k

stands for the excitation number (photon

number) of mode k, Oa

k

itself is a photon annihilation, Oa

†

k

a photon creation opera-

tor of mode k. For most quantum optical calcul ations, in particular with regard to a

compact description of protocols in quantum information theory, it is very conve-

nient to use this discrete single-mode picture. However, we will also encounter the

situation where we are explicitly interested in the continuous frequency spectrum

of “modes” that are distinct from each other in a discrete sense only with respect to

spatial separation and/or polarization. Let us briefly consider such a decomposition

of the electromagnetic field into a continuous set of frequency “modes”.

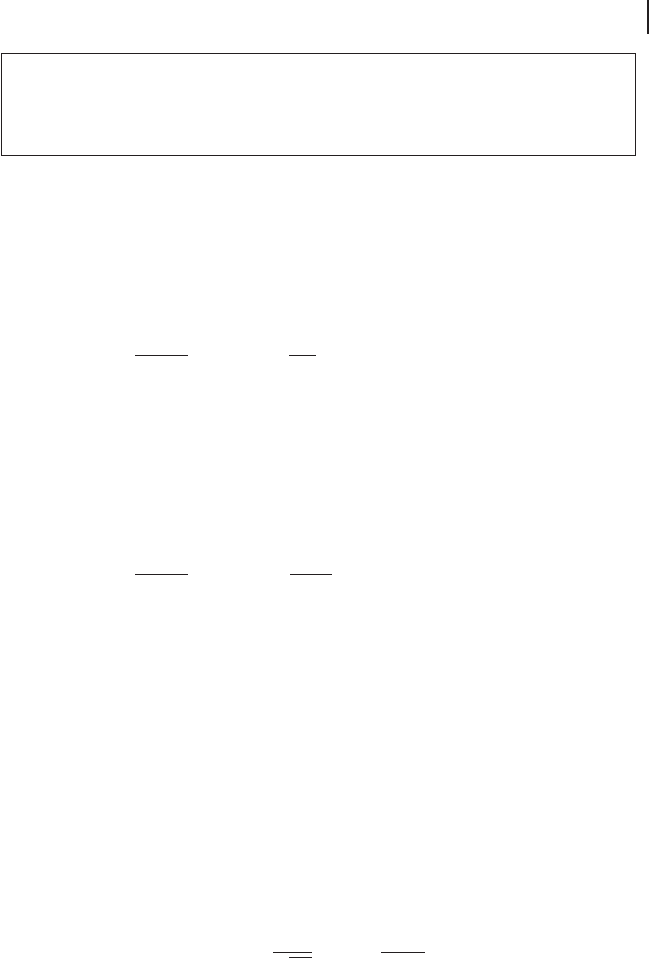

Quantized electromagnetic field

electric field:

O

E(r, t) D i

X

k

„ω

k

2ε

0

1/2

h

Oa

k

u

k

(r)e

iω

k

t

Oa

†

k

u

k

(r)e

Ciω

k

t

i

magnetic field:

O

B(r, t) D i

X

k

„

2ω

k

ε

0

1/2

h

Oa

k

k u

k

(r)e

iω

k

t

Oa

†

k

k u

k

(r)e

Ciω

k

t

i

Hamiltonian:

O

H D

1

2

Z

ε

0

O

E

2

C µ

1

0

O

B

2

d

3

r D

X

k

„ω

k

Oa

†

k

Oa

k

C

1

2

2.2 Quantum Optical States and Encodings 87

bosonic commutators:

[

Oa

k

, Oa

k

0

]

D

h

Oa

†

k

, Oa

†

k

0

i

D 0,

h

Oa

k

, Oa

†

k

0

i

D δ

kk

0

2.2.1.2 Continuous Modes

It seems in some ways more natural to describe the electromagnetic field vectors

by Fourier integrals rather than by Fourier series, although the continuous formal-

ism is less compact. The discrete mode expansion of the electric field in Eq. (2.20)

becomes, in the continuous limit [111],

O

E(r, t) D

i

(2π)

3/2

X

λ

Z

d

3

k

„ω

2ε

0

1/2

e

(λ)

h

Oa(k, λ)e

i(krω t)

Oa

†

(k, λ)e

i(krω t)

i

, (2.26)

where the mode index k has been replaced by the discrete polarization index λ and

the three continuous wave vector components. This corresponds to the limit of a

very large cube of size L !1. The discrete expansion of the magnetic field from

Eq. (2.21) now becomes [111]

O

B(r, t) D

i

(2π)

3/2

X

λ

Z

d

3

k

„

2ωε

0

1/2

k e

(λ)

h

Oa(k, λ)e

i(krω t)

Oa

†

(k, λ)e

i(krω t)

i

. (2.27)

The commutation relations in this continuous representation take the form

[ Oa(k, λ), Oa(k

0

, λ

0

)] D [ Oa

†

(k, λ), Oa

†

(k

0

, λ

0

)] D 0 , (2.28)

[ Oa(k, λ), Oa

†

(k

0

, λ

0

)] D δ

3

(k k

0

) δ

λλ

0

. (2.29)

Note that now the photon number operator must be defined within a finite wave

vector range, Oa

†

(k) Oa(k)d

3

k, which means the operator Oa(k)hasthedimension

of L

3/2

.

Finally, in terms of Glauber’s continuous Fourier integral representation from

Eq. (2.9), we can also write, for example, the electric field as

O

E

(C)

(z, t) D [

O

E

()

(z, t)]

†

D

1

p

2π

1

Z

0

dω

u „ω

2cA

tr

1/2

Oa(ω)e

iω(tz/c)

,

(2.30)

with

O

E(z, t) D

O

E

(C)

(z, t) C

O

E

()

(z, t), traveling in the positive-z direction (jkjD

ω/c) and describing a single unspecified polarization. The parameter A

tr

rep-

resents the transverse structure of the field (dimension of L

2

)andu is a units-

dependent constant [ for the units we have used in the Maxwell equations (SI

88 2 Introduction to Optical Quantum Information Processing

units), u D ε

1

0

, for Gaussian units, u D 4π]. Here, the photon number operator

must be defined within a fi nite frequency range, Oa

†

(ω) Oa (ω)dω, which means the

operator Oa(ω) has the dimension of time

1/2

. Compared to the discrete expansion,

a phase shift of exp(iπ/2) has been absorbed by the amplitude operator Oa(ω). The

correct commutation relations are now

[ Oa(ω), Oa(ω

0

)] D [ Oa

†

(ω), Oa

†

(ω

0

)] D 0, [Oa(ω), Oa

†

(ω

0

)] D δ(ω ω

0

) . (2.31)

2.2.2

Quadratures

Let us introduce the so-called quadratures by looking at a single mode taken from

the electric field in Eq. (2.20) for a single polarization [the phase shift of exp(iπ/2)

is absorbed into Oa

k

],

O

E

k

(r, t) D E

0

h

Oa

k

e

i(krω

k

t)

COa

†

k

e

i(krω

k

t)

i

. (2.32)

The constant E

0

contains all the dimensional prefactors. By using Eq. (1.42), we

can rewrite the mode as

O

E

k

(r, t) D 2E

0

Ox

k

cos(ω

k

t k r) COp

k

sin(ω

k

t k r)

. (2.33)

Apparently, the “position” and “momentum” operators Ox

k

and Op

k

represent the

in-phase and the out-of-phase components of the electric field amplitude of the

qumode k with respect to a (classical) reference wave / cos(ω

k

t k r). The choice

of the phase of this wave is arbitrary, of course, and a more general reference wave

would lead us to the single-mode description,

O

E

k

(r, t) D 2E

0

h

Ox

(Θ)

k

cos(ω

k

t k r Θ) COp

(Θ)

k

sin(ω

k

t k r Θ)

i

,

(2.34)

with the “more general” quadratures

Ox

(Θ)

k

D

Oa

k

e

iΘ

COa

†

k

e

CiΘ

ı

2, Op

(Θ)

k

D

Oa

k

e

iΘ

Oa

†

k

e

CiΘ

ı

2i .

(2.35)

These “new” quadratures can be obtained from Ox

k

and Op

k

through the rotation

Ox

(Θ)

k

Op

(Θ)

k

!

D

cos Θ sin Θ

sin Θ cos Θ

Ox

k

Op

k

. (2.36)

Since this is a unitary transformation, we again end up with a pair of conjugate ob-

servables fulfilling the commutation relation in Eq. (1.39). Furthermore, because

Op

(Θ)

k

DOx

(ΘCπ/2)

k

, the whole continuum of quadratures is covered by Ox

(Θ)

k

with

Θ 2 [0, π). This continuum of observables can be directly measured by h omodyne

2.2 Quantum Optical States and Encodings 89

detection, where the phase of the so-called local-oscillator field enables one to tune

between the rotated quadrature bases (see Section 2.6). The corresponding quadra-

ture eigenstates are the (unphysical) CV qumode stabilizer states, as introduced in

Section 1.3.2. A continuous set of rotated stabilizers is given by Eq. (1.71).

We shall mostly refer to the conjugate pair of quadratures Ox

k

and Op

k

as the po-

sition and momentum of qumode k, corresponding to Θ D 0andΘ D π/2. In

terms of these quadratures, the number operator becomes

On

k

DOa

†

k

Oa

k

DOx

2

k

COp

2

k

1

2

, (2.37)

using Eq. (1.39).

2.2.3

Coherent States

We have seen that the qumode states of the electromagnetic field can be expressed

in terms of the Fock basis, describing the photon or excitation number of the cor-

responding quantum harmonic oscillator. Another useful basis for representing

optical fields are the coherent states. As opposed to the Fock states, the coherent

states’ photon number and phase exhibit equal, minimal Heisenberg uncertainties.

In this sense, coherent states are the quantum states closest to a classical descrip-

tion of the field. They also correspond to the output states that are ideally produced

from a laser source.

Coherent states are the eigenstates of the annihilation operator Oa,

OajαiDαjαi , (2.38)

with complex eigenvalues α since Oa is a non-Hermitian operator. Their mean pho-

tonnumberisgivenby

hαjOnjαiDhαjOa

†

OajαiDjαj

2

. (2.39)

The quantum optical displacement operator is given by

O

D(α) D exp(α Oa

†

α

Oa) D exp(2ip

α

Ox 2ix

α

Op) , (2.40)

with α D x

α

C ip

α

and again Oa DOx C i Op. The displacement operator acting on Oa

in the Heisenberg picture yields a displacement by the complex number α,

O

D

†

(α) Oa

O

D(α) DOa C α . (2.41)

Coherent states are now displaced vacuum states,

jαiD

O

D(α)j0i . (2.42)

The Fock basis expansion for coherent states is

jαiDexp

jαj

2

2

1

X

nD0

α

n

p

n!

jni , (2.43)