Foyster E., Whatley C.A. A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600-1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

62 Charles McKean

outside Dundee, a village of jumbled cottages grew up in the 1780s and

1790s whose householders were entirely artisans and labourers.

46

Likewise,

the former islands of Netherhaugh and Overhaugh in the valley of the Gala

Water at Galashiels had been colonised by random cottages and unplanned

streets in the later eighteenth century, to the extent that the Scotts of Gala

felt compelled to lay out a more formal High Street on new ground to the

north-west, to ensure that the expanding lower town had the requisite

dignity.

47

Dorothy Wordsworth, predictably, much preferred the pictur-

esque thatched cottages to the new plainly elegant, two-storeyed, whinstone-

built High Street houses which she found ‘ugly’.

48

As in cities throughout Europe, control of fi re and sanitation were the

two principal causes of civic intervention. In most Scots burghs, the dean

of guild had the duty of overseeing construction and condemning decayed

buildings. A maximum height for buildings facing Edinburgh’s High Street,

for example, had initially been set at twenty feet, based upon the height of

the fi re ladder. Fearful of the continual fi res, it banned the use of thatch as a

roof covering in the early seventeenth century. After a disastrous fi re fanned

by timber foregalleries in 1651, Glasgow rebuilt its four principal streets in

four-storeyed ashlar upon arcaded ground fl oors for the merchants’ booths.

The resulting urbanism attracted the admiration of all visitors.

49

A century

later, in the 1760s, in explicit pursuit of modernism, but none the less

prompted by the need for fi re control, Dundee swept away its street-fronting

timber galleries, leaving the much plainer stone substructures behind. At

the same time, it removed the arcades that formerly ran in front of the

merchants’ booths at ground fl oor level. Although Perth still retained a few

‘wooden houses in the old style’, magistrates prohibited their rebuilding in

such fashion.

50

Scotland’s sewage regulations had not kept up with the increasing height

of urban tenements. Whereas Antwerp, for example, had introduced down-

pipes to carry sewage from upper storeys to street level sewers in the early

1500s, it was a standing reproach to Edinburgh that two hundred years later it

still had not done so – earning opprobrium from Jonathan Swift and Samuel

Johnson alike. Edmund Burt left a particularly vividly revolting description

of what happened in 1734, when the nightly 10 pm curfew permitted a uni-

versal slop-out from upper storey windows.

51

Edinburgh lagged behind even

Dundee in tackling the problem, and did not address it until the late 1760s.

Most aristocrats and country gentlemen maintained townhouses in their

regional urban centres, and some magnates had townhouses in several: the

earls and marquesses of Huntly, for example, had townhouses or villas

in at least Inverness, Fortrose, Aberdeen and Edinburgh. In a burgh like

Wigtown, the principal structures, apart from tolbooth and church, would

have been the townhouses of the regional gentry: Ahannays, Stewarts, Vaus,

McLellans, McCullochs, Dunbars, Agnews, Gordons and Kennedies.

52

The

most prominent house in a smaller burgh might well be the townhouse of a

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 62FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 62 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

Improvement and Modernisation 63

local laird, such as the Errol lodging in Turriff and the Glencairn lodging in

Dumbarton. In larger towns, they often took the French pattern of a court-

yard hotel, such as the Gowrie lodging in Perth’s Watergate, the Strathmartine

lodging in Dundee’s Vault, the Argyll lodging in Stirling’s Castle Wynd and

Moray House in Edinburgh’s Canongate.

Until the later eighteenth century, burgh society was heavily dependent

upon the gentry occupying their townhouses during the season, thus enrich-

ing its social life. As Edinburgh and then London proved to be the bigger

draw, the growing absence of their elites from small town life became a

problem. In 1799, Philetas lamented of Dundee that the country squires had

‘for the present, quitted the town. Like Cincinnatus, they have returned to

the ploughshares and to their seats and have thus become burgh seceders.’

53

The economy of its concerts, theatres and bookshops might depend upon

them, and their departure threatened the continuing health of its ‘society’.

Part of the changing urban agenda was the growing fashion for privacy.

Aristocrats had often chosen a site away from the market place when con-

structing a townhouse, preferring – like the marquess of Tweeddale’s or

Lady’s Stair’s lodgings – a location at the bottom end of a close. Perhaps that

was the only available plot of empty land; but it also detached them from the

noise of the High Street and the air was probably cleaner. The fi rst developer

(in modern parlance) to provide privacy in Edinburgh was Robert Mylne,

who constructed two large courtyards or squares of apartments: Mylne’s

Court and Miln’s Square. Set back from the High Street, they had a shared

but otherwise private court, organised refuse collection and an exclusive

social life of routs and balls. One can infer pressure for more of this from

the construction by James Brown of James Square, to the north of the High

Street in 1725. Home to people such as James Boswell (for it was to here that

he brought Dr Johnson back for tea), James Square provided substantial

apartments with outstanding views to the north. For all that, such apart-

ments still did not provide the public social life that the suburban ‘houses in

the English manner’

54

were expected to do. For breakfast with companions,

Boswell, for example, would normally go out from James Court to the coffee

houses in the courtyard of the Royal Exchange when he was not suffering

from a hangover.

When the Revd John Sime altered his middle ranking apartment in the

Lawnmarket, the agenda was one of privacy. Apartments like his contained,

in terms of descending size, a large bedroom, kitchen, a 12-foot square

parlour, a narrow hall, two closets and a windowless bedroom the size of

the bed. Sime altered that to form a formal hall, a much larger parlour and

a grander bedroom, squeezing the kitchen and reducing the other bedrooms

to miniature bed closets. The parlour presumably was for the reception of

guests who, one suspects, would no longer be allowed to penetrate else-

where.

55

The public and private parts of the apartment were separated.

Thus, polite society in the apartments of Edinburgh’s High Street itself was

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 63FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 63 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

64 Charles McKean

becoming more formal, irrespective of signifi cant changes emerging else-

where in the city.

IMPROVEMENT AND MODERNISATION

The Enlightenment retrospective perspective has distorted our perception

of the evolution of Scotland’s urban centres, and the processes of improve-

ment upon which they were all embarked. They were driven by the desire

to improve effi ciency, enhance trade and ennoble the burgh. A useful

distinction to help understand the diverging agendas can be made between

‘improvement’, that is, the bettering of what already existed, and ‘moderni-

sation’, that is, the importation and imposition of an a priori concept or idea.

Pre-eminently, new towns embodied the latter.

Improvement, which had begun before the ’45, proceeded swiftly after it.

Traffi c impediments had to go, so in the 1750s, Glasgow, Dundee, Edinburgh

and smaller towns like Irvine all removed their town ports (gates), and the

latter two also relocated their mercat crosses. Towns then reorganised them-

selves around the arrival of the turnpike roads (Tay Street in Dundee and

Union Street in Aberdeen, for example). Improvement also encompassed

street lighting, better paving of the streets, and – eventually – the establish-

ment of a police force with greater effectiveness than the city guards of

Edinburgh and Dundee or the night watch of Glasgow.

56

The original ‘Proposals’ for Edinburgh of 1752 contained as many sugges-

tions for improving the existing city – the addition of a Royal Exchange, the

construction of access bridges and the construction of a new building for the

records of Scotland (not to say the rebuilding of the university) – as they did

for modernising it through the addition of a new town.

57

Moreover, the latter

was explicitly restricted to ‘people of certain rank and fortune only’. This

exclusive aristocratic suburb would fl ourish in a creative partnership with

the existing High Street in which all professionals, merchants, commerce and

places of entertainment were expected to remain. A vivid illustration of the

contrast between the two urban lifestyles, according to Robert Chambers,

was that the New Town’s urban parade of George Street was so sublimely

grand as to make the very respectable people who had previously managed to

cut a dash in the High Street feel outclassed and embarrassed.

58

Disliking the promiscuous mixing of ranks exemplifi ed by all classes using

the same staircase,

59

the devisors of this new civil society preferred people to

be ordered, categorised and classifi ed. Streets were intended to be occupied

by people of a similar rank; and separate streets were provided for those of

different rank. That applied equally to the small plantation towns on moors

in the north-east, whose principal, central street usually contained houses

altogether more substantial than the cottages in back streets. In pursuit of

the sublimation of the individual to the collective, feu conditions would

ensure that all houses in the same street were identical in scale and virtually

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 64FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 64 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

Improvement and Modernisation 65

in appearance. The new towns would express order through a rational rec-

tangular plan with well-built houses to a standard design. Non-conforming

uses were rigorously excluded. At the peak of the ‘new town’ boom in the

1820s, even minuscule communities such as Langholm, Nairn and Banff pro-

posed to embellish themselves with a new town far beyond their purse, as an

essential symbol of forward thinking.

In 1745, the Gentleman’s Magazine had commented on how fashionable

living was beginning to emerge on Edinburgh’s ‘Society Green [where] they

have lately begun to build new houses there after the fashion of London,

every house being designed for only one family’.

60

These houses after the

English manner, ‘inhabited’, as Forsyth put it, ‘by a single family from top

to bottom’,

61

became Argyll and Brown Squares. Pennant approved of the

‘small but commodious houses in the English fashion’ being built on the

twenty-seven acres of George Square to the south,

62

and praised the new

houses ‘in the modern style’ in St Andrew Square because they were ‘free

from the inconveniences attending the old city’ (emphasis added).

63

(See Figure

2.7.). The strong implication, reiterated by much later historiography, is that

there was a pent up demand from Edinburgh citizens to move from antique

tenements to more modern houses.

64

The facts, however, do not support

it. It took until 1823 – or over half a century – before the fi rst New Town

was complete.

65

No Enlightenment Club met in the New Town. Their pre-

ferred location remained the large, vaulted, windowless taverns like Johnny

Dowie’s tavern near the foot of Carrubber’s Close in the Old Town. It was

not until c. 1795, almost thirty years after Edinburgh’s New Town project

was begun, and ten years after isolation had been ended by the opening of

the Earthen Mound, that the fi rst New Town began to move to completion.

Scotland’s ancient capital city began to be regarded as an ‘Old Town’ only

after the turn of the century (Figure 2.8).

The Enlightenment model adopted in Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Perth and

most of Scotland was that of low terraced houses in an exclusive residen-

tial suburb.

66

However, when Lisbon rebuilt itself after the earthquake in

the later 1750s with all the regularity and rectangularity of Enlightenment

thinking, it did so with fi ve- and six-storeyed blocks of apartments with com-

mercial premises at street level – appropriate for a European commercial

city centre. The dwellings of Glasgow’s fi rst new town (now the Merchant

City) around Wilson Street were likewise apartments above an arcaded com-

mercial ground fl oor; and when Robert and James Adam designed a series

of street blocks for George Square, Ingram Street and Stirling’s Square, that

is what they designed (Figure 2.9). The apartments in Dundee’s town centre

had been refi tted with panelling, plasterwork and Adam fi replaces so lavishly

during the eighteenth century

67

that moving to new houses on the ‘new town’

plots of Castle and South Tay Streets proved simply to be not attractive

enough. The stances remained unbuilt. Dundee and Glasgow were improving

where Edinburgh and Aberdeen were modernising.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 65FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 65 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

66 Charles McKean

Moreover, even in Edinburgh’s Princes Street, things were not what they

seemed. In 1781, the mason Alexander Reid built what looked like a new

house on his fi rst stance: in fact, it was four spacious apartments in a block

designed to resemble a house.

68

That became the norm in the cross streets: a

group of Scottish traditional apartments wholly disguised as a classical villa

(Sir Walter Scott’s house at 39 Castle Street being an excellent example).

Towns and landlords alike sought to ensure that the character of their

new settlements was rigidly enforced through feu conditions governing

use, appearance and scale. Purchasers were forbidden from construct-

ing brickworks or carrying out any other industry in the garden.

69

The

number of storeys of the houses was prescribed, together with their facing

material (usually ashlar) and a slated roof (dormer windows were expressly

forbidden in Edinburgh’s fi rst new town). The width of streets was fi xed

– Dundee’s were unusually narrow at 40 feet (c. 13 metres) – and houses

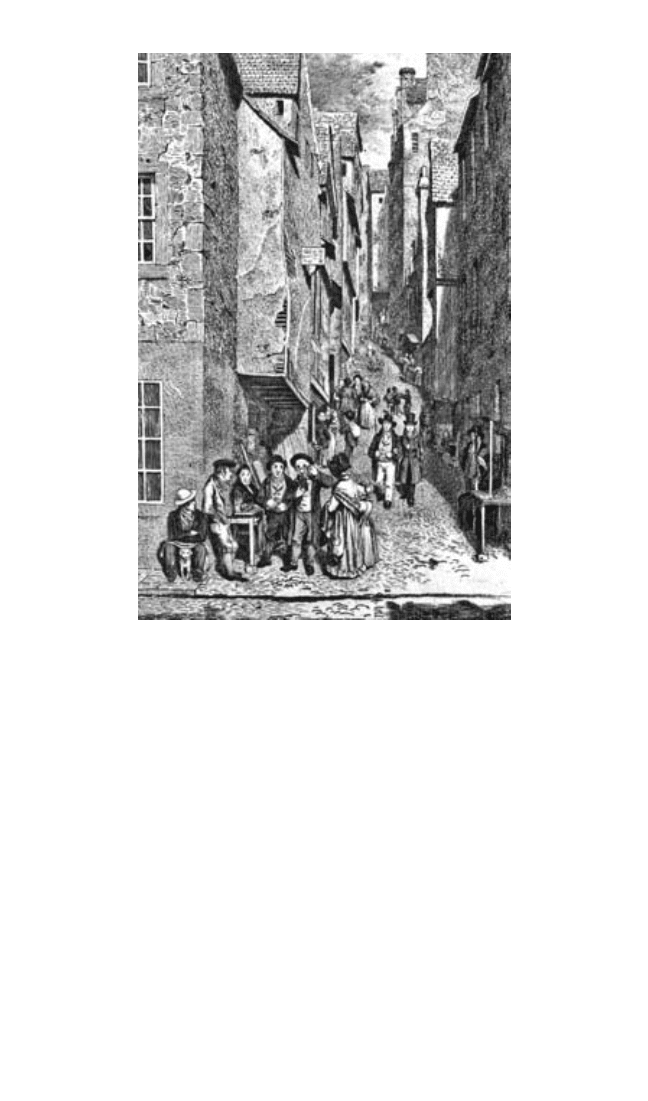

Figure 2.7 Liberton’s Wynd (now under George IV Bridge), Edinburgh, drawn in 1821

by Walter Geikie. This affectionate record of the close that housed the celebrated Johnny

Dowie’s tavern (and its Enlightenment Clubs) emphasises the density and mixed nature

that the Enlightenment was so anxious to rationalise.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 66FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 66 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

Improvement and Modernisation 67

were forbidden to encroach upon the pavement. Within these restrictions,

design was left open:

70

broad homogeneity and elegance was suffi cient. It

was only when Edinburgh was feuing out Charlotte Square in the 1790s

that developers were made to follow a pre-ordained design; and the fact

that it took until 1823 for Charlotte Square to be completed implies that

the cost of Robert Adam’s design (as well as having to stump up for the

maintenance of the square gardens), depressed the market and pushed

purchasers toward the more economical designs of the second new town

downhill to the north.

As the new suburbs were occupied, older burgh centres were progres-

sively abandoned. Robert Chambers recorded that the last persons of quality

to live in Edinburgh’s Old Town – Governor Ferguson of Pitfour and his

brother – quit the Lawnmarket with a great party in 1817 (almost exactly fi fty

years after the new town was initiated).

71

Judging from John Strang’s Glasgow

and its Clubs, the wealthy of Glasgow had by then long since quit its High

Street for the three ‘new towns’ that had been constructed to the west.

72

By

the end of the eighteenth century, therefore, formerly elite apartments were

declining in status, occupied by lesser ranks, then by poorer people, inevi-

tably to become multi-occupied by the destitute, with the squalor so vividly

recorded by the new medical offi cers of health in the 1840s.

Figure 2.8 Edinburgh by John Elphinstone. Edinburgh on its rock (right), drawn by

John Elphinstone in picturesque darkness and variegated roof-line in contrast to the white

regularity of the houses of the New Town then inching slowly westward from St Andrew

Square. The Nor’ Loch has been completely drained, but the Mound has not yet begun

(completed 1787). It was an exemplifi cation of the rational order of the new civil society in

contrast to the arbitrariness of the old.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 67FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 67 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

68 Charles McKean

RURAL CHANGE

To a large degree, the modernisation of rural Scotland was led by govern-

ment institutions: the Forfeited Estates Commissioners and the Fisheries

Society. The Forfeited Estates had been responsible for the orderly laying

out of cottages for the settlement of veteran soldiers as part of its pacifi ca-

tion strategy. Pennant admired the ‘neat small houses inhabited by veteran

soldiers settled here in 1748’ which he saw at Tummel, although he observed

mordantly ‘in some few places this plan succeeded, but they did not relish

an industrial life and, as soon as the money was spent, left their tenements

to be possessed by the next comer’.

73

The Board of Manufactures was preoc-

cupied with processes and subsidies to foster improved industrial skills, but

was probably not directly involved in dwelling construction, although it may

well have infl uenced it. By contrast, the Fisheries Society was responsible for

new fi shing towns ranging from Ullapool to Wick and Tobermory, and pro-

moted standardised house designs for simple, symmetrical cottages which

largely presaged the humbler rural house of nineteenth-century Scotland.

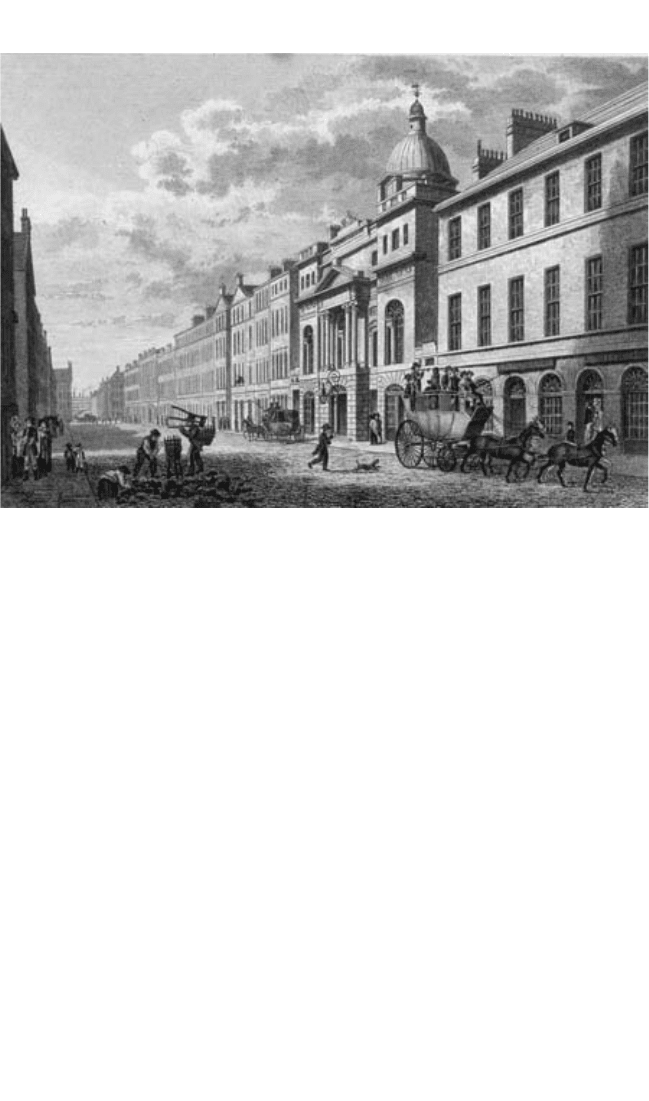

Figure 2.9 Glassford Street, Glasgow, drawn by John Knox in 1828 for Glasgow and its

Environs. When the Trades House on the right was designed by Robert and James Adam

in 1791, it was fl anked originally by plain blocks of handsome apartments above arcaded

commercial premises (as can still be seen on the right). That was urban living in the old

Scoto/European manner in contrast to the terraces of individual houses soon to emerge in

Glasgow’s later new towns.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 68FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 68 29/1/10 11:13:4829/1/10 11:13:48

Improvement and Modernisation 69

In contrast to these sturdy incomers, the humblest of self-built cottages

could indeed be regarded as temporary, formed, as they were of soluble

materials like turf, divots and timber. Pennant found Scotland a country of

civilised people living in uncivilised conditions (Figure 2.10). The inhabitants

of the cottages in Dollar roofed with sods were ‘extremely civil, and never

failed to offer brandy or whey’.

74

He regarded the dwellings in the soon-to-

be-cleared burgh of Fochabers as wretched, and was equally unimpressed

with the ‘very miserable’ peasant houses of Morayshire, constructed entirely

of turf. That he was evaluating condition rather than type is indicated by his

praise for some cottages in Angus built of ‘red clay or sods, prettily thatched

and bound by straw ropes’,

75

whereas barely twenty miles away in Braemar,

he found ‘the houses of the common people in these parts shocking to

humanity, formed of loose stones and covered with clods which they call

devots, or with heath, boom or branches of fi r; they look, from a distance,

like so many black mole hills’.

76

Fifty years later, the poet laureate, Robert

Southey, travelling through Scotland with Thomas Telford, was appalled

when he reached Ross: ‘I have never, not even in Galicia, seen any human

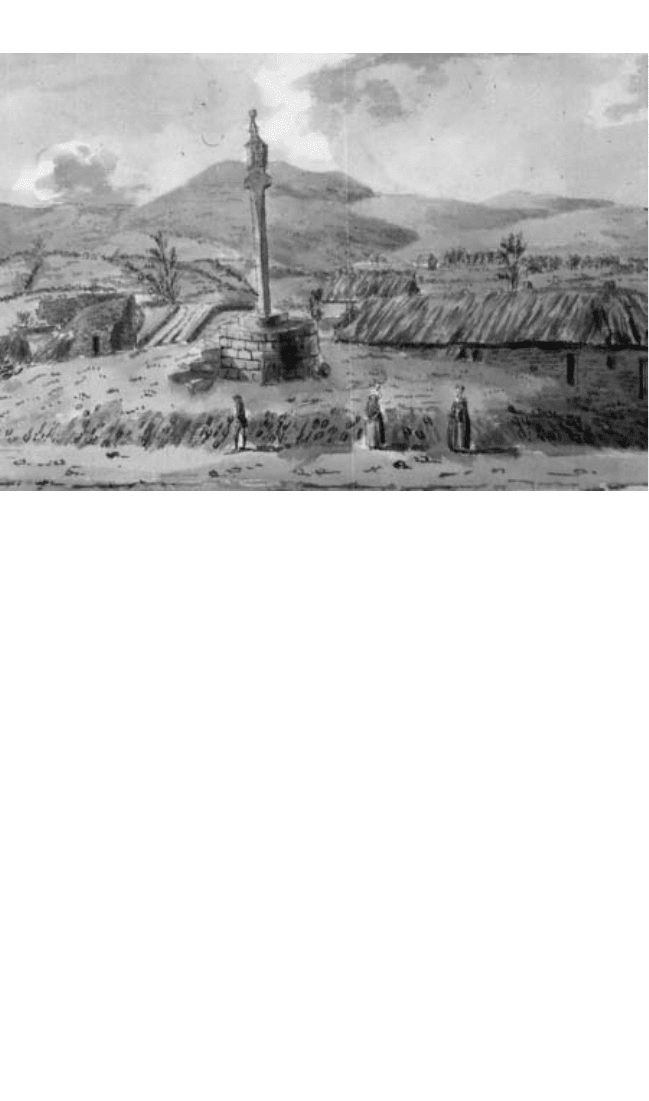

Figure 2.10 Burgh of Barony, Dumfriesshire. A small burgh (presumably a burgh of

barony) in Dumfriesshire drawn in the 1780s either by Francis Grose or his friend the

antiquarian, Robert Riddell. That it is a burgh of barony is indicated by its market cross

and the date 1692 (the high point of founding burghs of barony). Houses are thatched,

and there is no sign of a church or tolbooth. This community probably vanished during the

improvement era. Source: Riddell Manuscript collection. Reproduced courtesy of the Society

of the Antiquaries of Scotland/National Museums of Scotland.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 69FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 69 29/1/10 11:13:4829/1/10 11:13:48

70 Charles McKean

habitations as bad as the Highland black-houses . . . The worst . . . are the

bothies – made of very large turfs, from four to six feet long, fastened with

wooden pins to a rude wooden frame.’

77

Enlightenment commentators found the black house offensive not just

because of the conditions within. It affronted their sense of decorum.

However, the anthropologist Helen MacDougall, writing from a Highland

perspective, has warned of the danger of confusing the condemnation of

poor conditions with the condemnation of a cultural type of building.

Referring specifi cally to Garnett’s descriptions, she wrote:

such a superfi cial view of passing travellers was not unusual at the time – especially

if they had not been privileged to experience the very real quality to be found in

the homes of the fi ne type of Highlander who met hardship and poverty with

dignity. Nor would they appreciate the beauty of the traditional building materials

which blended with the landscape from which they were drawn.

78

That she was correct is indicated by the fact that the black house remained a

dwelling type of choice in the Highlands until the twentieth century.

The most common category of rural house in the later eighteenth century

was the improved model cottage. Since most of the surviving smaller rural

houses in Scotland date from the nineteenth century, records for earlier

types of dwellings are much more scarce, hence the dependence in this

chapter on eye-witness accounts. It is also diffi cult to generalise about rural

Scotland since practice varied throughout the country. That view differs

from Naismith in Buildings of the Scottish Countryside.

79

Focusing exclusively

upon post-1750s cottages, Naismith concluded that there was a remark-

able homogeneity, since he discovered standardised proportions ‘in every

county in Scotland’. Some generalised proportions, and standardisation

in, for example, doors and windows, might have been expected from the

plethora of improvement books. From the early eighteenth century onward,

burgeoning agricultural societies had discussed the improved agricultural

building at length,

80

and county surveys of agricultural improvement con-

tained prototypes, supplemented by pattern books, such as The Rudiments of

Architecture.

81

George Robertson’s General View of Agriculture in the County

of Midlothian

82

is much more specifi c. It contains a delightful drawing of the

recommended improved farmhouse and steading; and its resemblance to the

farmhouses in Kinross described by Forsyth cannot be purely coincidental.

There was an accepted way of doing things, but differences were greater than

similarities. There is a clear inference from Naismith’s research (although he

himself did not make it) that districts with higher land values had narrower

and taller cottages to reduce their footprint, and that location, weather and

shelter still mattered.

It is not always clear who undertook the construction of the new houses

in this modernising world. Sometimes, new farms were built by the land-

lord, a rent being charged according to size (in the Highlands, they were

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 70FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 70 29/1/10 11:13:4829/1/10 11:13:48

Improvement and Modernisation 71

assessed by their roof structure or number of timber couples); sometimes

the landlord expected the tenant to build for himself. George Dempster, the

improving landlord of Skibo, left construction to the tenants: ‘Mr Dempster

. . . encouraged the tenants to improve their little spots of land, and to build

houses for themselves of more durable materials.’

83

Most of the houses in

mid-eighteenth-century Kerrera ‘were put up by the family who occupied

them, and repaired and rethatched as required’. But the arrival on the island

of the professional builder, John MacMartine, was regarded as a harbinger

of signifi cant change to come.

84

If the occupier had been left to himself, his

house would have been a vernacular structure; if built or instructed by the

landlord, it would have followed the fashion of the time for the appropriate

rank of building. As Helen MacDougall has put it, ‘buildings, made from

materials at hand in the landscape by people who were going to use them,

have been succeeded by buildings partly or wholly constructed of imported

materials by men whose profession was building’.

85

Forsyth found that improvement, modernisation and thereby wealth

were unevenly distributed throughout Scotland. Whereas farmhouses in

Clackmannanshire were single storey with a garret, generally thatched or

covered in pantiles,

86

those in Kinrossshire were two storey, ‘substantially

built, covered with slate, neatly fi nished, and with every necessary conven-

ience for the accommodation of the farmer’s family’. Even Kinross’s cottages

were now well lit, built of stone and lime, covered with thatch and 16 feet

wide.

87

By contrast, the farmhouses and offi ces of Cromarty remained ‘mean

and wretched hovels’ (from the description, it appears that they were black

houses), anathema to improving Lowland eyes.

88

Even post- Improvement

cottages for poorer tenants and mechanics could be fairly miserable: for

every occasion Forsyth praised cottages built of stone and clay, lime harled,

with a small window or two even with panes of glass instead of the former

opening, there were others, as down in Tweeddale, that were just ‘miserable

hutts’ – single storey, ill built and thatched.

89

Interior furnishings remained

sparse.

90

The worst conditions could be found in Argyll. As late as 1807, Forsyth’s

typical Argyllshire farmhouse was:

a parcel of stones up to the height of fi ve or six feet without mortar, or with only

mud instead of it; and these walls, burdened with a heavy and clumsy roof, need

to be renewed with almost every lease; and the roof generally so fl at at top that

one might securely sleep on it, is seldom water tight . . . The cottages here are

for the most part mean and wretched hovels, except where a tradesman here and

there may have found proper encouragement to build for himself a commodious

habitation.

91

That was indeed the rub. People needed encouragement and the initiative

had to lie with the landlord. Forsyth was particularly impressed by the gen-

tlemen of Ross who had devised various means of inducing Highlanders to

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 71FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 71 29/1/10 11:13:4829/1/10 11:13:48