Foyster E., Whatley C.A. A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600-1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

52 Charles McKean

– had fallen into severe decay in the eighteenth century. Robert Southey

found Hamilton, for example, ‘a dirty old town with a good many thatched

houses in the street implying either poverty or great disregard of danger from

fi res’.

2

A signifi cant proportion of the country’s Renaissance country seats

were in similar trouble. They had been abandoned as being too unfashion-

able for the Enlightenment world, so when Dorothy Wordsworth passed

through Dumfriesshire in 1803, she observed many of the ‘gentlemen’s

houses which we have passed have an air of neglect and even of desolation’.

3

Conditions in many vernacular rural cottages had become such as to inspire

the most evangelical moderniser. Wordsworth again: ‘The hut was after the

Highland fashion, but without anything beautiful save its situation; the fl oor

was rough and wet with the rain that came in at the door . . . The windows

were open’ [that is, no frame, shutter or glass].

4

By the end of the eighteenth

century, decay was also infecting the ancient urban centres as higher status

apartments, abandoned by their inhabitants for the new towns, slid down

the social ladder.

The overriding theme, however, is the infl uence of the Enlightenment and

the impulse of modernity. Its desire to create a new civil society, free from

the arbitrary rule of the past, was characterised by a new sense of ordered

community. In order to forge a modern Scotland, it condemned the history,

culture and architecture of its past – particularly that of the Stuart mon-

archs. Thus, Robert Heron in 1799: ‘The improvement, the industry and

the riches, lately introduced into Scotland, form a striking contrast with the

barbarity, the indolence and the poverty of former times.’

5

The expression

of modernity lay in the planning or construction of almost 500 new towns,

elite suburbs or grid-iron manufacturing villages.

6

For the most part, the

power of ordinary country folk below the Highland line to build for them-

selves where and how they wished was replaced by a requirement to conform

to the new agenda of regular rectangular modernity, more or less as a moral

imperative.

RANK

In his manuscript maps, prepared c. 1585–1608, Timothy Pont distinguished

up to nine scales of rural building, the top four of which appear to be

depictions of different ranks of country seats.

7

The remainder vary from

individual buildings to strings of what look like cottages with chimneys

indicating cottowns, kirktowns and similar rural settlements. His maps also

appear to indicate other rural structures, such as windmills, mills, kilns and

tide mills.

8

If this interpretation is correct, visible hierarchy in buildings was

intentional.

In the west Highlands, for example, the manse (where the laird had been

prepared to pay for new one) might stand out, but the principal middle

ranking building, the tacksman’s house, would be considerably grander. In

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 52FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 52 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

Improvement and Modernisation 53

general form, the tacksman’s house was a rather larger and more elaborate

version of the ubiquitous middle ranking building of Lowland Scotland –

the ‘Improvement’ farmhouse – a sturdy, usually harled, three-bay house,

occasionally double-pile (that is, two rooms deep) adjacent to the improved

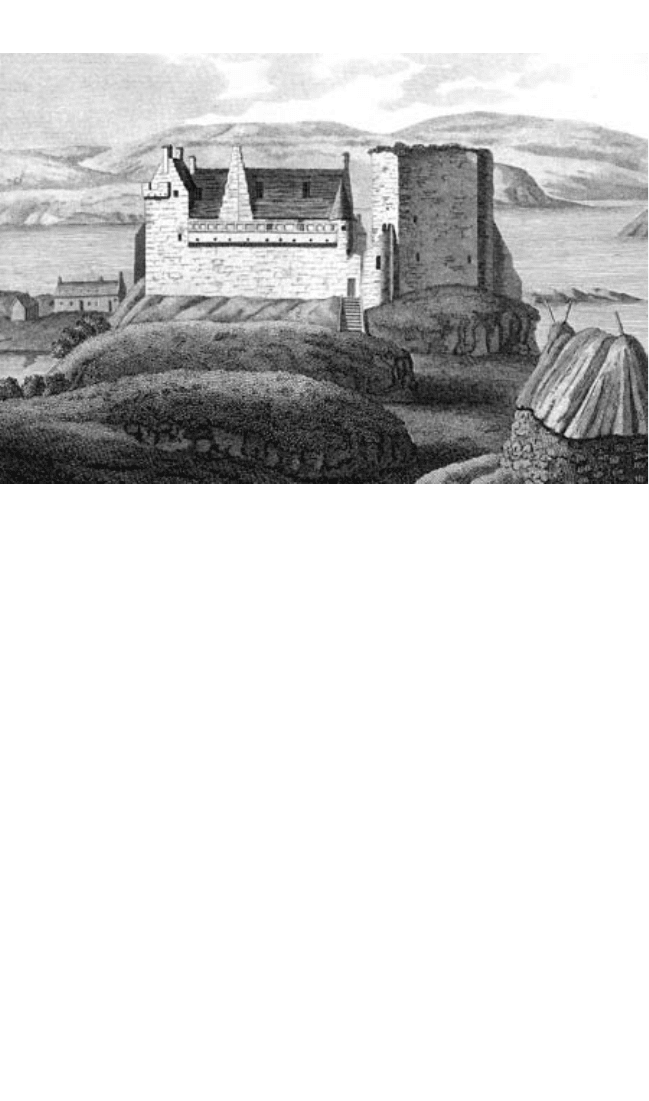

steading. A 1790 engraving of Dunvegan, Isle of Skye by Tom Cocking

undertaken for Captain Francis Grose (Figure 2.1) shows two houses in the

neighbourhood of the semi-ruined castle: the one in the foreground is a long,

thatched roof ‘black house’, a building type that escaped total obliteration

only because its walls were of stone (see later), in contrast to another in

the background: regularly built, presumably new stone cottages with that

particular symbol of modernism the pitched slated roof. The drawing itself

conveyed its own value judgement.

9

Changes in the fortunes or rank of the occupier would be marked on the

exterior of even the humblest homes: at its simplest being carved initials

on a door lintel, or a pedimented or otherwise elaborated doorway. Many

single-storey cottages were initially extended into the attic space then for-

malised with further storeys added on top. The joints and junctions that

evidenced this progression were never intended to be visible: they would

have been obscured by the building’s harled overcoat, thus giving the desired

impression of being wholly newly built. The ruse would be spotted only

Figure 2.1 View of Dunvegan, Skye from the east, drawn for Captain Francis Grose’s

Antiquities of Scotland, Vol. II (London, 1797). Note the black house (right foreground)

as compared with modern slated cottages (left background) and the fact that the oldest part

of the stronghold lies in ruins.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 53FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 53 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

54 Charles McKean

if the building fell foul of the ‘rubblemania’

10

fashion causing the harling

to be cloured off in the early nineteenth century. Only the very smartest

village houses might be graced with a new façade of expensive squared stone

(ashlar).

Rank was equally important in towns. In Scotland’s largest Renaissance

towns – notably Dundee and Edinburgh

11

– occupiers of all apartments

shared a common stair – an ‘upright street’ as the Enlightenment con-

demned it

12

– even though the rank of those who occupied each storey

differed considerably. The street level, accessed separately, was occupied

by merchants’ booths and storage, usually screened by arcades of loggias,

of which the best surviving examples are to be found in Elgin and at

Gladstone’s’ Land, Edinburgh.

13

In 1835, Leith Ritchie interpreted the

already historic living pattern of upper tenement fl oors for Walter Scott’s

English readers: ‘The fl oor nearest heaven, called the garrets, has the great-

est number of subdivisions; and here roost the families of the poor. As we

descend, the inmates increase in wealth or rank; each family possessing an

“outer door”.’

14

The primary apartment was on the piano nobile or prin-

cipal fl oor, occupied by persons of the highest rank of those who lived in

such properties.

15

Being generally undefended and walled for burgh control and customs

purposes only,

16

Scottish towns had evolved without the centrifugal defen-

sive plan with multiple squares and plazas normal in European walled cities,

but had instead spread out in a linear manner. Their urban ‘outdoor rooms’

were restricted to two: the high gait or market place, from which the wind

was as far as possible excluded; and the service centre with its urban stench

(in Edinburgh the Grassmarket, and in Dundee the Fishmarket) through

which the wind was welcome.

17

The highest value merchant apartments were

those nearest to the market place,

18

the centre of urban life. In 1560, Dundee

rearranged its public buildings – a new tolbooth, fl eshmarket, grammar

school and public weighhouse – to form a self-conscious new axis between

the market place and the harbour. In both Edinburgh and Dundee, the catch-

pull (Scots for tennis court) lay on one edge of the town toward one of the

gates.

The extent to which Scots towns shared the European pattern of identifi -

able craft districts is not yet clear. In the early nineteenth century hammer-

men, for example, were concentrated in Edinburgh’s West Bow where the

noise was ferocious: it ‘was one of the most noisy quarters of the city – the

clinking of coppersmiths’ hammers, the bawling of street criers, ballad

singers and vendors of street merchandise’.

19

Alexander Campbell observed

of Perth in 1800:

Different streets and lanes appear to have been very early allotted to different

craftsmen who, with few exceptions, still inhabit the same quarters. The skinners,

for instance, live in one street, the weavers in a second, the hammermen in a third,

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 54FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 54 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

Improvement and Modernisation 55

the shopkeepers or, as they are generally called in Scotland, the merchants, in a

fourth, and so on.

20

But such a strong identifi cation of a craft with a particular part of the city has

been much more diffi cult to establish in Scotland than in Europe. A recent

survey of occupations in a section of Edinburgh’s High Street has revealed

that crafts were scattered rather than concentrated; although the dirtier or

noisier activities were located away from the High Street and stables were

down in the Cowgate.

21

It has likewise proved extraordinarily diffi cult to

assess the pattern in Dundee, although its cordiners or shoemakers appear to

have been clustered around the West Port, its bucklemakers by the Wellgate

and its bakers and brewers near, naturally, to the town’s mills.

22

Rank in later Renaissance Scotland was a pliable concept, and there were,

perhaps, more opportunities for an ambitious person to change rank than

during the Enlightenment – particularly if they were involved in construc-

tion. James Murray, time-served wright and son of a wright, rose to become

the royal architect and died as a landed gentleman: Sir James Murray of

Kilbaberton.

23

Some decades later, Andrew Wright, a rural joiner from the

village of Glamis who worked for the earl of Strathmore at his ancient pater-

nal seat, was paid by the latter in the form of a grant of the lands of Rochilhill,

which he renamed Wrightsfi eld, took the name Wright of Wrightsfi eld

24

and

died a minor laird.

VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

Vernacular architecture, taken literally, means ‘untutored’, and refers to

buildings erected by non-professionals, using materials available to hand

and following structural precedents handed down over the generations. It

has been suggested that materials for a truly vernacular building would have

been obtained within 100 metres of the site,

25

but there is some evidence of

scarce timber being carried greater distances. Materials for smaller urban

houses such as stone and divots – and perhaps occasionally timber – may

well have been obtained from the burgh’s common lands, which was the

usual source of fuel. The limits on sourcing materials would be transformed

where sites were close to waterborne transport. Even the mode of using

an identical material differed locality to locality,

26

and it is from this close

association between vernacular architecture and its locality – the form,

shape, texture and colour of the materials used to construct the vernacular

architecture – that regional and local identity derives (Figure 2.2). It was very

regionally specifi c. Thomas Pennant noted how the cottages in Breadalbane,

for example, were roofed with broom,

27

as compared with the heather,

straw, turves or reeds he saw elsewhere.

Although short pieces of timber were in widespread use for the roof struc-

tures of rural houses, particularly near great forests such as Rothiemurchus,

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 55FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 55 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

56 Charles McKean

Scotland was very short of long-span structural timber, which it tended to

import from Norway through the principal ports of Leith and Dundee. It

is in those towns, therefore, that there is the greatest evidence for the use

of signifi cant structural timber in urban construction.

28

Otherwise, by the

mid-fi fteenth century the predominant Scottish structure had become that

of stone, and the predominant building craft that of the mason.

29

Some

locations retained an alternative technology. In the Carse of Gowrie and

Garmouth (Moray), for example, there was suffi cient clay for ordinary

people to construct walls of clay bool,

30

a process recorded by Pennant:

The houses in this country [Moray] are built with clay: after dressing with clay,

and working it up with water, the labourers place it on a large stratum of straw

which is trampled into it and made small by horses; then more is added until it

arrives at a proper consistency, when it is used as a plaister, and makes the houses

very warm.

31

People developed a natural sense of appropriate location for rural cot-

tages and built in the manner of their ancestors; in constructing vernacular

cottages they sought comfort, warmth and shelter, dryness, adjacent cul-

tivatable land, with shelter for beasts. It is likely that most were built by

the householder, his friends, relatives and neighbours. The consequence is

that the structure had to be simple and the techniques easily understood.

Cottages were orientated to maximise light within, set near water and, where

possible, dug deep into a slope for protection against the wind. Improvement

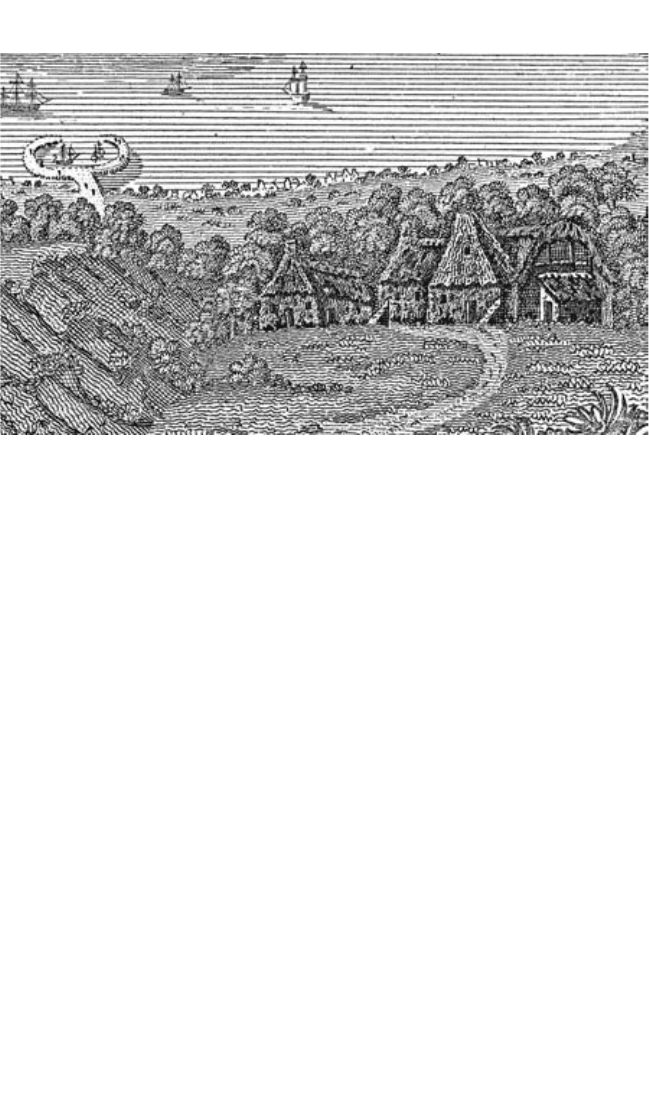

Figure 2.2 Vernacular houses near the shore at Lamlash Bay, Arran, drawn by J.C. and

published in Views in Scotland (London, 1791). These fairly substantial buildings appear

to have been timber-framed and thatched, and their upper storeys reached by external stairs.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 56FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 56 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

Improvement and Modernisation 57

came only gradually and innovation almost never. The pursuit of comfort

naturally extended to the interior and its furnishings and may explain the

cane hood of the Orkney chair as a protection against draughts in those

windswept islands.

There appears to have been a fundamental divide between the quality

of cottages on either side of the Highland line. Even making allowances

for the inevitable distortion caused by a post-Enlightenment perspective,

the constantly reiterated contrast between the interior of Lowland cottages

– plastered or painted, with glazed windows, perhaps with rooms or cham-

bers within, and a well-tended garden attached – and the virtually single-

chambered unplastered, unpainted and miry earthen-fl oored Highland black

house, shared with its sprawling livestock, cannot be ignored. The scientist

Thomas Garnett recorded of Port Sonachan:

These cottages are in general miserable habitations. They are built of round stones

without any cement, thatched with sods and sometimes heath; they are generally,

though not always, divided by a wicker partition into two apartments, in the larger

of which the family reside; it serves likewise as a sleeping room for them all . . .

The other apartment is reserved for cattle and poultry when the last do not choose

to mess and lodge with the family.

32

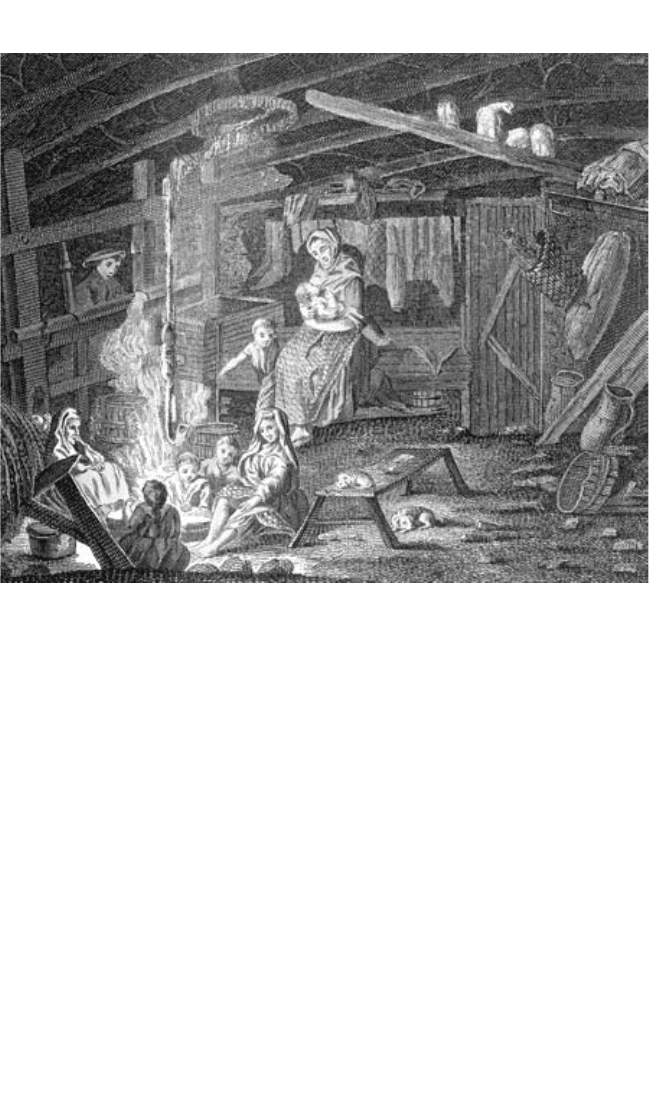

(See Figure 2.3)

Given that, it is scarcely believable that he found even worse conditions in

cottages at Torosay, Mull where ‘the mud fl oors were in general damp, and

in wet weather quite miry’.

33

When arriving in Luss, Dorothy Wordsworth

observed: ‘Here we fi rst saw houses without windows, the smoke coming out

of the open window places’; and of a later inn she added:

The walls of the whole house were unplastered. It consisted of three apartments

– the cow house at one end, the kitchen or house in the middle, and the spence at

the other end . . . The rooms were divided not up to the rigging, but only to the

beginning of the roof, so there was a free passage of light and smoke from one end

of the house to the other.

34

Nor was it just the black house. The King’s House inn in Glencoe had

‘naked walls’: ‘Never did I see such a miserable, such a wretched place.’

35

Generally, these eye witness accounts have been supported by later research

– particularly by Bruce Walker and Alexander Fenton, and by the publica-

tions of the Scottish Vernacular Buildings Working Group.

36

ANCILLARY BUILDINGS OF THE COUNTRY SEAT

Until the urban expansion of the mid-eighteenth century, the country seat

remained both the centre of the rural economy and the focus of the major-

ity of Scots. Enfolding the ‘main house’ of the country seat, therefore, were

the buildings of the everyday support services required for maintenance of

both household and estate. In addition to guest lodgings, the gallery, library

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 57FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 57 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

58 Charles McKean

and offi ces there were also the woman house, the dairy, brewery, gill house,

bakehouse, coal house, bottle house, laundry, gardener’s house, apple

houses, hen houses, barns and many others.

37

Probably refl ecting the crucial

role played by the need for self-suffi ciency in the country seat, the gardener

was nearly always provided with a purpose-designed house, frequently built

into the walls of the kitchen garden.

38

Within the house itself, the most

important day-to-day role in the early eighteenth century was played by

the housekeeper – the chief executive of the hotel, as it were – and that was

refl ected in the much larger suite of rooms she occupied than those of the

butler,

39

whose emergence as the principal fi gure of the household appears to

date only from the early nineteenth century.

If you could afford to, you would pay others to construct your buildings

rather than build them yourself. It was customary to approach craftsmen on

a ‘separate trades’ contract, whereby each craft contracted separately with

the client, usually leaving the client with signifi cant duties in terms of provid-

ing the materials, scaffolding, food and accommodation for the workers.

40

However, there is some evidence that by the late seventeenth century, some

Figure 2.3 The interior of a cottage on Islay, drawn in 1772, probably by Moses

Griffi ths for Thomas Pennant’s Tour in Scotland. A single central space, a fi re without

a chimney, window without frame or glass, with a box bed behind, and chicken on the roof

trusses.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 58FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 58 29/1/10 11:13:4629/1/10 11:13:46

Improvement and Modernisation 59

of the more powerful craftsmen were emerging as what we would now call

‘main contractors’. James Bain, for example, king’s master wright, was acting

not just as a wright in the houses of Glamis and Panmure, but as a timber

supplier and contractor employing all the other wrights, masons, plasterers

and painters.

41

The penalty for acting in what we would regard as a ‘modern’

manner was duly visited upon him when his aristocratic clients disputed his

bills and refused to pay. Since he had already paid his sub-contractors, Bain

went bust.

42

From the later seventeenth century, the maze of high-walled enclosures

that enfolded the Renaissance country seat, providing the microclimates

necessary for cultivation, began to be removed. The outer entrance court

of barns, stables and coal house was replaced by a back court invisible to

visitors, and the principal farm became the main farm or mains, banished

out of sight with its barnyards. Back courts were, in turn, replaced in the

later eighteenth century when country estates were remodelled according to

the dictates of the Picturesque. The country seat now appeared proudly as a

free-standing monument in the landscape and stables or farm squares were

carefully placed as picturesque objects to be glimpsed from the entrance

drive. The capital was made available by the provisions of the 1770 Entail

Improvement Act, which permitted landowners to pass on the cost of estate

improvements to their descendants.

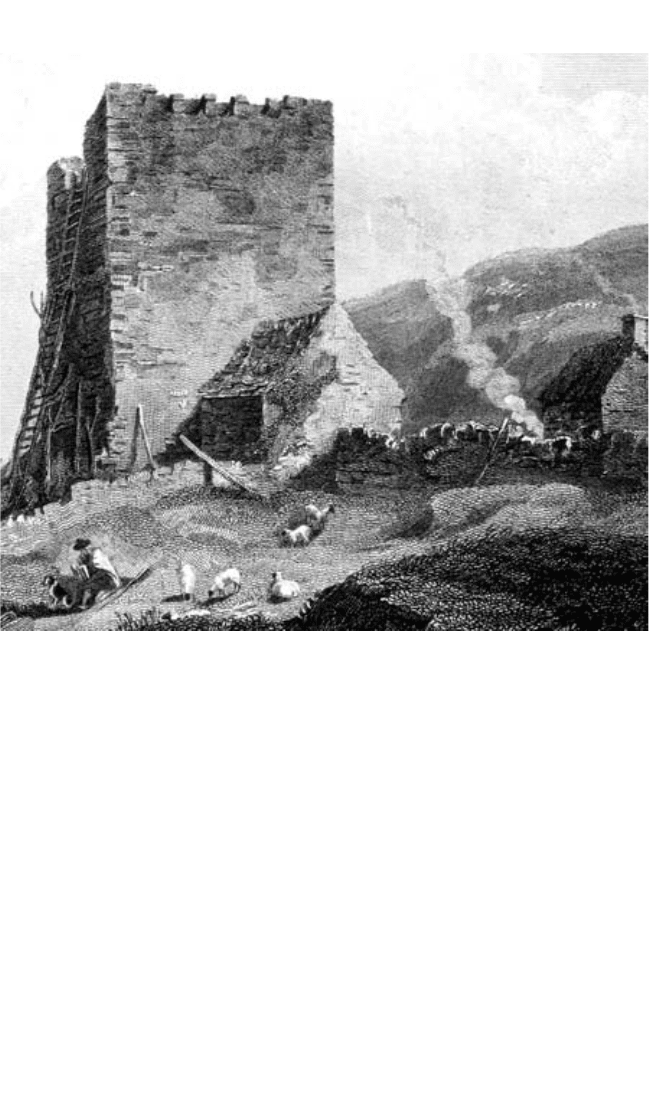

A good number of estates, however, remained unimproved. Contemporary

illustrations of abandoned country houses reveal derelict demesnes in semi

or total abandonment, occupied in a makeshift manner – and only by

the poorest (Figure 2.4). At New Tarbat, ‘once the magnifi cent seat of an

unhappy nobleman who plunged into a most ungrateful rebellion’, Pennant

observed, ‘the tenants, who seem to inhabit it gratis are forced to shelter

themselves from the weather in the very lowest apartments, while swallows

make their nests in the bold stucco of some of the upper’.

43

URBAN FORTUNES

A number of Scots towns fared so badly in the eighteenth century that rescue

by a new turnpike road or growth in the herring fi shery had been their only

means of survival. They had either been in the wrong place – as Renfrew was

overwhelmed by its aggressive near-neighbour Paisley,

44

or else geographi-

cally bypassed – like Selkirk, Nairn and Tain. Whithorn, for example, had

prospered greatly as a pilgrimage centre before the Reformation, but was

in a state of collapse by the seventeenth century. By the mid-eighteenth

century, most houses in the upper end of town had mouldered into ruin,

their plots then subdivided into two narrow weavers’ cottages (Figure 2.5).

When a measure of prosperity returned, however, some of those plots were

reassembled to make larger houses to the former scale, so rendering urban

archaeology extremely challenging. A turnpike road, however, might bring

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 59FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 59 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

60 Charles McKean

inns and stables, followed by banks and in some cases – Tain being a good

example – by an academy for the education of the regional gentry.

A preoccupation with neo-classical suburbs and grid-iron new towns

is a distorting prism through which to study Scottish burghs. There were

many more with a largely unchanged street pattern, dominated by thatched

houses – like Melrose or Jedburgh or, occasionally punctuated by the taller,

slate-roofed, dressed-stone townhouses of local gentry, such as the majestic

Balhaldie Lodging in Dunblane

45

(Figure 2.6), than there were towns that had

undergone a modernist makeover. The fi ctional burghs of Gudetown and

Dalmailing portrayed in John Galt’s two novels, Annals of the Parish (1821)

(thought to be Irvine) and The Provost (1822), are quite probably accurate in

their depiction of small town life in Scotland, preoccupied more with paving

the streets, lighting them, maintaining civic order and keeping tabs on emi-

grants and immigrants rather than with grandiose schemes. Moreover, there

was also substantial ‘unplanned’ urban colonisation. In the Scouringburn,

Figure 2.4 Goldieland Tower, Borders, drawn by T. Clennell in 1814 for Scott’s Border

Antiquities. The tower is probably used for storage (hence the ladder), whereas the once

noble buildings of the inner court appear to have been cut down and squatted by shepherds.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 60FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 60 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47

Improvement and Modernisation 61

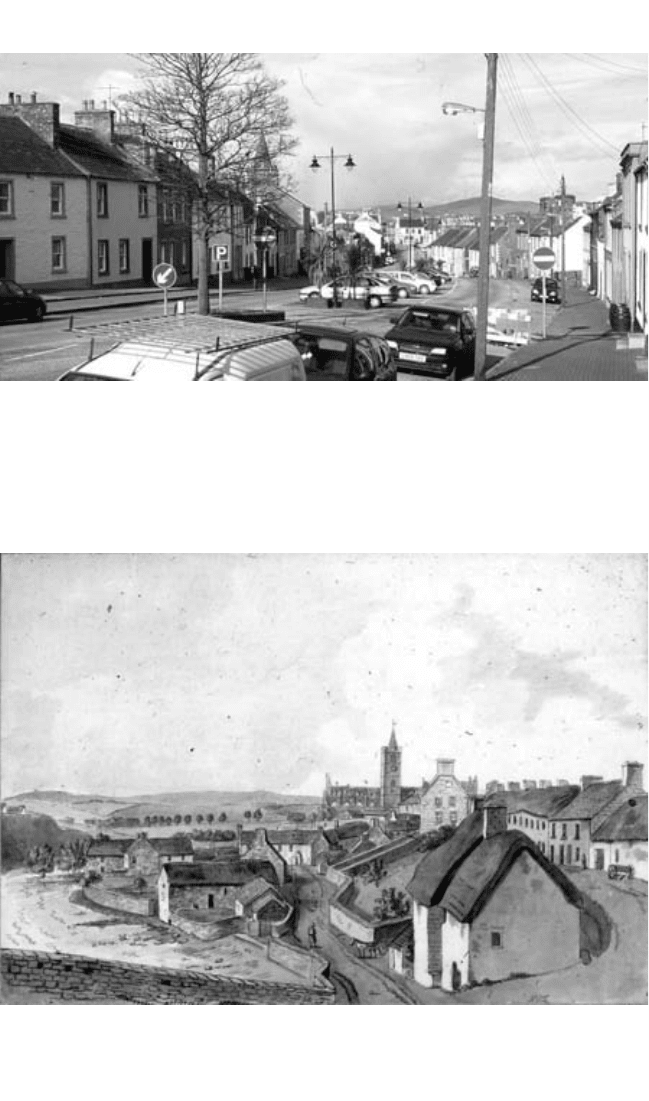

Figure 2.5 The upper part of the Main Street of Whithorn. The view downhill to the

central ceremonial space of the town, and further to the service end of the town, would

have been blocked by a large tolbooth on the site of the palm trees. This upper part was

probably the gathering point of pilgrims. The houses were once grander, became ruined

and were subdivided, and then enlarged again in the early nineteenth century.

Source: C. A. McKean.

Figure 2.6 Dunblane from the south, painted by Captain Francis Grose in the 1780s.

The burgh is very quiet – almost rural – and most houses are harled and thatched. The

exception is the tall, ashlar (and presumably slate-roofed) townhouse of Drummond of

Balhaldie. Reproduced by permission of the National Galleries of Scotland.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 61FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 61 29/1/10 11:13:4729/1/10 11:13:47