Foyster E., Whatley C.A. A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600-1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

102 Deborah A. Symonds

world in which everyone was bound to someone, and ‘nobody in those times

thought of pleasing themselves’. As Mure refl ected, ‘The established rule

was to please your company[.]’

71

CONCLUSION

Throughout the early modern period, the adult life cycle of marrying, giving

birth and dying in Scotland was usually accomplished within a network of

social ties that formed the basis of the political and economic state, for the

most part lived and experienced at parish level. In the eighteenth century

conditions improved: famine abated; child mortality declined; and after

Culloden the kind of military action that resulted in large numbers of

fatalities relocated from Scotland to North America and India. The weather

began to release its grip, or at least its worst effects could usually be over-

come, although the threat to human life and the suffering that wet, wind

and cold could exert on families and individuals by no means disappeared.

Yet, paradoxically, as nature relented in the eighteenth century and as other

demographic challenges receded, the essential foodstuffs that might have

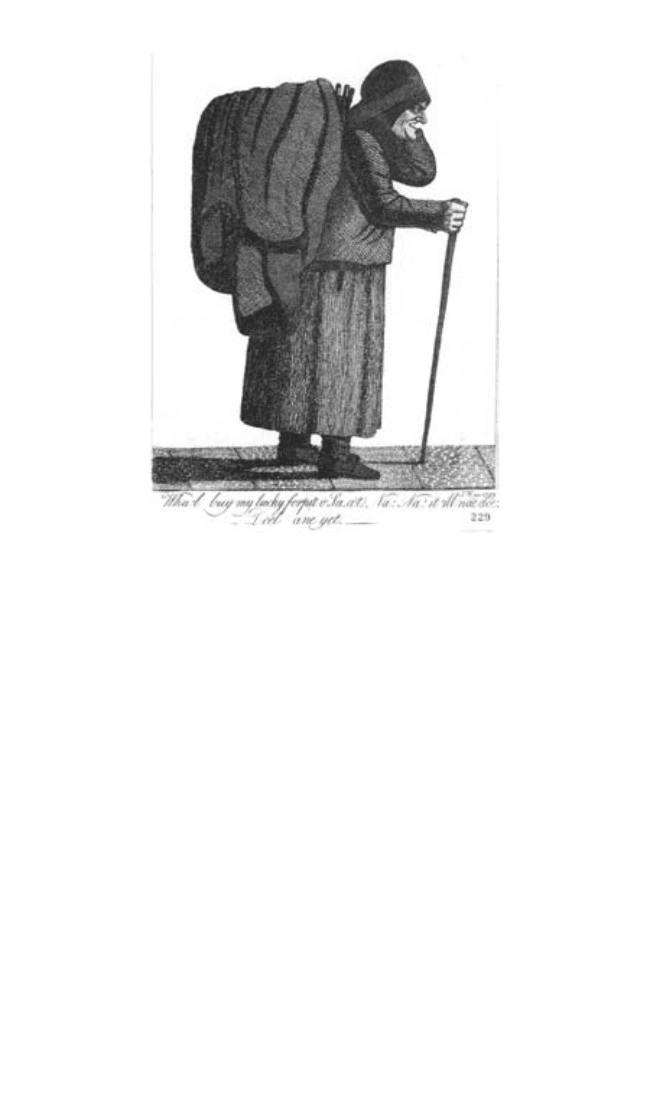

Figure 3.5 ‘Saut Wife’, taken from John Kay, A Series of Original Portraits and

Caricature Etchings (Edinburgh, 1837–8). Salt wives, fi sh wives and many other peddlers

supplied city households with food and other necessities, highlighting both the growing

demand and the growing populations of the late eighteenth century.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 102FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 102 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

Death, Birth and Marriage 103

made conception and childbirth easier and more frequent, and prolonged

life, may for the poorer sections of society have become harder to acquire as

the market economy in agricultural produce strengthened. Vagrancy and the

presence of the poor continued to pose problems for the authorities in town

and country, especially during periods of food shortage. The sanctity of mar-

riage continued to be eroded by fornication for some, while others delayed

entry to the matrimonial state.

72

The erratic and regionally variable illegiti-

macy fi gures that may have marked the degrees to which ordinary people had

hoped for or given up on marriage were joined after 1690 by prosecutions

for infanticide.

73

Infanticide has never been absent from any society, but it

had to be visible to be prosecuted. The spectre of the single woman murder-

ing her infant was surely a sign of a new kind of despair.

74

None the less, the

population slowly increased. Life found a way, amid the new diffi culties that

replaced the old horrors catalogued by Malthus, and perhaps John Callendar

got to die in his bed, an old man.

Notes

1. For John Callendar, see CS299/4 in National Archives of Scotland (NAS), West

Register House (WRH), Edinburgh. A search of digitised birth records, available

at: www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk shows twenty-nine John Callanders or Callandars

born in Falkirk between 1671 and 1723, or twenty-nine in fi fty-two years.

2. For the Statistical Account (OSA) for Falkirk, see the Edina site, available at:

http://stat-acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/link/1791-99/Stirling/Falkirk/. Surgeons had risen

in status and training by the early eighteenth century; see Helen M. Dingwall,

Physicians, Surgeons and Apothecaries. Medical Practice in Seventeenth-Century

Edinburgh (East Linton, 1995), pp. 72–9; and on the rise of the Old Poor Law,

see Rosalind Mitchison, The Old Poor Law in Scotland. The Experience of Poverty,

1574–1845 (Edinburgh, 2000), pp. 3–43; and on the moral obligation to help, see

Michael Flinn (ed.), Scottish Population History (Cambridge, 1977), pp. 10–12.

3. On children, whose high death rate was perhaps the most obvious and famil-

iar form of death, see T. C. Smout, A History of the Scottish People 1560–1830

(London, 1985), pp. 252–3; and ‘The population problem’, ch. XI, pp. 240–60.

4. On the physicians, see Helen M. Dingwall, A History of Scottish Medicine

(Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 72–4; for traditional healers, see pp. 95–102; and also

Dingwall, Physicians, Surgeons and Apothecaries.

5. Flinn, Scottish Population History, pp. 11–12.

6. On population growth, see R. E. Tyson, ‘Contrasting regimes: population growth

in Ireland and Scotland during the eighteenth century’, in S. J. Connolly, R. A.

Houston and R. J. Morris (eds), Confl ict, Identity, and Economic Development:

Ireland and Scotland, 1600–1939 (Preston, 1995), pp. 64–76.

7. See Harold Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society (London, 1969).

8. Flinn, Scottish Population History, p. 4; his suspicion of slow growth or even a

decline in population has been confi rmed, see Tyson, ‘Contrasting regimes’, pp.

64–7.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 103FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 103 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

104 Deborah A. Symonds

9. See descriptive material, available at: http://edina.ac.uk/stat-acc-scot/access/sub-

service.html.

10. OSA on line, available at: http://stat-acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/link/1791-99/Perth/

Comrie/11/180.

11. OSA on line, available at: http://stat-acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/link/1791-99/Perth/

Comrie/11/183.

12. OSA on line, available at: http://stat-acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/link/1791-99/Perth/

Comrie/11/178.

13. On the Scottish Enlightenment, see, among innumerable works, primary and

secondary: Jane Rendall, The Origins of the Scottish Enlightenment 1707–1776

(New York, 1978); Karl Miller, Cockburn’s Millennium (Cambridge, MA, 1976);

William Ferguson, Scotland 1689 to the Present (Edinburgh, 1968), pp. 198–233;

and the recent readable overview by James Buchan, Crowded with Genius (New

York, 2003).

14. See Flinn, Scottish Population, pp. 3–4, 45–51; James Gray Kyd (ed.), Scottish

Population Statistics including Webster’s Analysis of Population 1755 (Edinburgh,

1975), pp. 7–81.

15. Robert Chambers, Domestic Annals of Scotland, from the Revolution to the Rebellion

of 1745 (Edinburgh, 1861), pp. 136–7, 195–9.

16. Chambers, Domestic Annals, p. 606.

17. Chambers, Domestic Annals, p. 196 – Chambers is colourful; for recent scholar-

ship on famine in Aberdeenshire, and riots in particular, see Karen J. Cullen,

Christopher A. Whatley and Mary Young, ‘King William’s ill years: new evi-

dence on the impact of scarcity and harvest failure during the crisis of 1690s on

Tayside’, The Scottish Historical Review, LXXXV (October 2006), 272–3.

18. Chambers, Domestic Annals, p. 348.

19. Chambers, Domestic Annals, p. 197.

20. Revd J. L. Buchanan, Travels in the Western Hebrides from 1782 to 1790 (Waternish,

1997 edn.), pp. 73–4; R. M. Inglis, Annals of an Angus Parish (Dundee, 1888),

p. 144.

21. A. Spicer, ‘Rest of their bones: fear of death and Reformed burial practices’, in

W. G. Naphy and P. Roberts (eds), Fear in Early Modern Society (Manchester,

1997), pp. 167–83.

22. For Alexander Webster and his 1755 census, see A. J. Youngson, ‘Alexander

Webster and his “Account of the Number of People in Scotland in the Year

1755”’, Population Studies, 15:2 (November, 1961), 198–200; and Kyd, Scottish

Population Statistics, pp. 7–81.

23. See, for example, G. Marshall, Presbyteries and Profi ts: Calvinism and the

Development of Capitalism in Scotland, 1560–1707 (Edinburgh, 1980).

24. For the clerk, see NAS, CH2/545/3/7, for October and November 1747. The old

parish registers, or OPRs, have survived sketchily; see the online resource, avail-

able at: www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/content/help/index.aspx?r=554&405.

25. On erratic records of baptisms, see Cullen, Whatley and Young, ‘King William’s

ill years’, p. 265; on the nature of Scottish records, and demography (although

most data is, due to the scarcity of records, from the late eighteenth century

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 104FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 104 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

Death, Birth and Marriage 105

to 1861), see R. A. Houston, ‘The demographic regime’, in T. M. Devine and

Rosalind Mitchison (eds), People and Society in Scotland, Vol. I, 1760–1830

(Edinburgh, 1988), pp. 9–26.

26. For Alison and Harvey, see Revd James Anderson, The Ladies of the Covenant,

Memoirs of Distinguished Female Characters, Embracing the Period of the Covenant

and Persecution (New York, 1880), pp. 272–99.

27. See the letter of Adam Smith to William Strahan, 9 November 1776, in Ernest

Campbell Mossner and Ian Simpson Ross (eds), The Correspondence of Adam

Smith, vol. VI (Indianapolis, IN, 1987), p. 217.

28. Letter, Adam Smith to William Strahan, 9 November 1776, in Mossner and

Ross, Correspondence of Adam Smith, p. 217.

29. Smout, A History of the Scottish People, pp. 283–7 on housing.

30. Philippe Aries, Western Attitudes Towards Death: From the Middle Ages to the

Present (Baltimore, MD, 1974); and by the same author, The Hour of Our Death

(New York, 1981).

31. Adam Smith to William Strahan, 9 November 1776, in Mossner and Ross,

Correspondence of Adam Smith, p. 217.

32. Henry Hamilton (ed.), Selections from the Monymusk Papers (Scottish History

Society, Edinburgh, 1945), pp. 15–17.

33. W. C. Mackenzie, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun His Life and Times (Edinburgh,

1935), p. 310.

34. For Lady Baillie, see Anderson, Ladies of the Covenant, p. 457.

35. See Sheila M. Spiers, The Kirkyard of Auchindoir Old & New (Aberdeen, 1987),

p. 15.

36. See the OSA for Auchindoir, available at: http://stat-accscot.edina.ac.uk/

link/1791-99/Aberdeen/Auchindoir; on the OSA generally, see Maisie Steven,

Parish Life in Eighteenth-century Scotland: A Review of the Statistical Account (OSA)

(Aberdeen, 1995). The absence of births between 1697 and 1702 probably refl ects

the impact of the great famine: see Cullen, Whatley and Young, ‘King William’s

ill years’, pp. 250–76.

37. On the movement of female servants, see Ian D. Whyte and Kathleen Whyte,

‘The geographical mobility of women in early modern Scotland’, in Leah

Leneman (ed.), Perspectives in Scottish Social History (Aberdeen, 1988), pp.

83–106.

38. Or it may be coincidence; see the OSA for Edinburgh, available at: http://stat-

acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/link/1791-99/Edinburgh/Edinburgh/6/561.

39. G. Parker, ‘The “Kirk by Law Established” and the origins of the “taming of

Scotland”: St Andrews, 1559–1600’, in Leneman, Perspectives, pp.17–18.

40. On the extent of and patterns for illegitimate births, see Leah Leneman and

Rosalind Mitchison, ‘Scottish illegitimacy ratios in the early modern period’,

Economic History Review, 2nd series, XL: I (1987), 50; this is a brief introduction

to their work, see also their Girls in Trouble (Edinburgh, 1998) and Sexuality and

Social Control: Scotland 1660–1780 (London, 1989).

41. For Mary M’Millan see John Cameron (ed.), The Justiciary Records of Argyll and

the Isles, vol. I (Edinburgh, 1949), pp. 110–12.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 105FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 105 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

106 Deborah A. Symonds

42. Cameron, Justiciary Records, pp. 124–5.

43. Cameron, Justiciary Records, pp. 133–4.

44. Cameron, Justiciary Records, pp. 196–98.

45. See the OSA for Glassary, or Kilmichael-Glassary, available at: http://stat-acc-

scot.edina.ac.uk/link/1791-99/Argyle/Glassary/13/658.

46. Oral composition and transmission were fi rst identifi ed in the Homeric epics by

Albert B. Lord, Singer of Tales (Cambridge, MA, 1960), and later demonstrated

among a large group of Scots ballads by David Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk

(London, 1972).

47. For the B text of ‘Child Waters’, stanzas 30–35, from the singing of Anna Gordon

Brown, collected in Aberdeenshire in 1800, see Francis James Child, The English

and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. II (New York, 1965), pp. 87–9.

48. E. Sanderson, Women and Work in Eighteenth-Century Edinburgh (London, 1996),

p. 53.

49. For the midwives, see the South Circuit court records, NAS JC12/11, October

1762, case of Agnes Walker; for William Hunter, and further commentary on

Agnes Walker, the young woman suspected of infanticide, see Deborah A.

Symonds, Weep Not for Me: Women, Ballads, and Infanticide in Early Modern

Scotland (University Park, PA, 1997) pp. 73–83, 143–50.

50. Sanderson, Women and Work, pp. 60–4.

51. On infant mortality and birth rates, see Tyson, ‘Contrasting regimes: population

growth’, pp. 70–1.

52. See papers of the Forfeited Estates Commission, NAS E 626/17/1, 2. The absence

of a grate, common to other rooms in this inventory, suggests the room was

unused at the time.

53. See Mitchison and Leneman, Girls in Trouble, pp. 40–52; and Kenneth M. Boyd,

Scottish Church Attitudes to Sex, Marriage and the Family, 1850–1914 (Edinburgh,

1980), pp. 46–50.

54. Elizabeth Mure, ‘Some remarks on the change of manners in my own time.

1700–1790’, in William Mure (ed.), Selections from the Family Papers preserved at

Caldwell; 1696–1853 (Glasgow, 1854), pp. 263–4.

55. See, for example, A. B. Barty, The History of Dunblane (Stirling, 1994), p. 85.

56. Flinn, Scottish Population, p. 7.

57. Mitchison, Old Poor Law, pp. 3–19.

58. On the Poor Law Act, see Mitchison, Old Poor Law, pp. 22–44. For the other

demographic data, see Flinn, Scottish Population, pp. 1–11.

59. On divorce and separation in Scotland, see Leah Leneman, Alienated Affections:

The Scottish Experience of Divorce and Separation, 1684–1830 (Edinburgh, 1998);

for England, see Elizabeth Foyster, Marital Violence: An English Family History,

1660–1857 (Cambridge, 2005). Divorce came to Scotland with the Reformation,

and was possible for both adultery and desertion by 1573; see Boyd, Scottish

Church Attitudes, pp. 47–9; and on handfasting, see A. E. Anton, ‘“Handfasting”

in Scotland’, The Scottish Historical Review 37: 124 (October 1958), pp. 89–102.

60. In the online dictionary of the Scots Language, available at: www.dsl.ac.uk, hand-

fasting also has an economic connotation, in reaching an agreement to employ

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 106FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 106 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

Death, Birth and Marriage 107

someone; see too R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage: Scotland, 1603–1745

(London, 1983), p. 9.

61. Angus Archives, Abroath Brewers Guild, MS 444/5/71, Ann Smith to John

Auchterlony, 25 March 1739.

62. R. A. Houston, ‘Women in the economy and society of Scotland, 1500–1800’,

in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte (eds), Scottish Society 1500–1800 (Cambridge,

1989), pp.120–1.

63. Houston, ‘Women’, pp. 142–3.

64. On feelings in one marriage that crossed the seventeenth and eighteenth centu-

ries, see Lady Murray of Stanhope, Memoirs of the Lives and Characters of the Right

Honourable George Baillie of Jerviswood and of Lady Grisell Baillie (Edinburgh,

1824), pp.83–5. See, too, H. and K. Kelsall, Scottish Lifestyle 300 Years Ago

(Edinburgh, 1986).

65. Mure, ‘Some remarks’, pp. 260, 266.

66. J. Dwyer, The Age of Passions: An Interpretation of Adam Smith and Scottish

Enlightenment Culture (East Linton, 1998), pp. 101–39.

67. Henry Mackenzie, The Man of Feeling, Project Gutenberg text online, available

at: www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext04/mnfl 10h.htm, third paragraph in chapter

thirteen.

68. Child, English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. II, ballad number 73, A text,

stanzas 4–8, p. 182. There are seven texts of this ballad in Child; the A text was

fi rst printed in 1765 in Bishop Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry;

see Child, vol. II, p. 179.

69. Marriage and The Heart of Mid-Lothian both appeared in 1818; they can be use-

fully compared with Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1802), and Hannah More’s

Coelebs in Search of a Wife (1810).

70. Symonds, Weep Not, pp. 56–67.

71. Mure, ‘Some remarks’, p. 268.

72. Population growth was slow in Scotland in the later eighteenth century, which is

consistent with rising age at fi rst marriage in some areas, migration and skewed

sex ratios; see T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation (New York, 1999), p. 151, on

population growth.

73. On illegitimacy, briefl y, see Leneman and Mitchison, ‘Scottish illegitimacy

ratios’, pp. 41–63; the authors rely on the role of the kirk locally to explain ille-

gitimacy, rather than economic factors.

74. See Symonds, Weep Not, pp. 127–78 on the 1690–1820 period; and on the

second half of the century in the south-west, see Kilday, ‘Maternal monsters’.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 107FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 107 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

Chapter 4

Illness, Disease and Pain

Helen M. Dingwall

INTRODUCTION

In the early modern period, illness and pain were considerable social level-

lers. Status could not prevent the onset of disease, and treatment was centred

on the same basic principles, whether prescribed by the most eminent physi-

cian in the land, or a wise woman in a remote Highland village. Few escaped

illness or injury, and it is this area which illustrates commonalities among

social groups perhaps more than any other aspect of everyday life. In the area

of health and disease, the everyday experience was in many ways common to

all, regardless of social status.

Historians of medicine in recent times have tried to analyse medicine

‘from below’, in terms of the experiences and perspectives of the patients,

rather than assessing the role of ‘great doctors’ or of institutions, and this has

helped to bring new perspectives to the topic.

1

Health was an unavoidable

concern for everyone, and the social construction of ‘un-health’ was multi-

faceted, manifesting itself in ways which varied widely, but which also shared

common features throughout society. The social construction of illness

was shaped by many factors, including demography, social status, religion,

superstition and tradition.

Change over time is a key element in any aspect of the historical process,

but continuity is equally important. Toward the end of the eighteenth

century, body structures were explained more scientifi cally and some towns

had hospitals in which to treat the sick, but these developments affected

most people indirectly, and often not at all. Despite new knowledge, there

was a considerable delay in its application to new treatments. Complex

surgery was not possible until the advent of anaesthetics and antiseptics in

the mid-nineteenth century. Other factors which had a major impact on

everyday health and disease included the state of war or peace, the vagaries

of the economy and the occurrence of epidemic disease.

The main factor dominating the sphere of health for almost the entire

period was that medicine was based on the classical, humoral philosophy

which had been articulated by Hippocrates and Galen in the heyday of

ancient Greece and Rome, and added to by Arabic medicine. These com-

posite infl uences produced what is termed ‘western medicine’.

2

This took

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 108FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 108 29/1/10 11:13:5129/1/10 11:13:51

Illness, Disease and Pain 109

a strongly holistic view of life, health and disease, and the state of the indi-

vidual was very much related to the rhythm of the seasons, astrology and the

balance of bodily humors.

Religion had long been at the root of medical treatment, but also – and

quite naturally – alongside a complex array of other beliefs, including witch-

craft and the supernatural. Early modern Scots were perhaps more sophis-

ticated in their ability to embrace beliefs which nowadays might be seen as

mutually exclusive in a much more compartmentalised society. This meant

that Christian faith could be combined easily with incantations or rituals

derived from pagan times or from white witchcraft. The witchcraft prosecu-

tions of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries did not detract from

belief in the supernatural process, good as well as evil. Examples are found

easily in the relatively sparse records which survive from the earlier part of

the period, such as a cure for migraine:

Take foure penny wecht of the root of pellitory of Spayne [nettle family, often

grown in physic gardens], and half penny wecht of spyngard and grynd thame and

boyle them in gude vynegar, and quhen it is cauld put into an sponefull of hony

and ane saucer of mustarde, and medle them weill togither and hauld theirof in thy

mouth ane sponefull at once as long as ane man may say two creeds

3

Watches were not widely available, but everyone knew how long it took

to say a creed. In most cases involving drugs (often referred to as Galenicals

because of their derivation from the works of Galen), the ingredients were

similar, whether dispensed by a professional physician or a lay healer. This

was partly because of the common philosophical outlook on the causes of

disease and its treatment (which included a signifi cant degree of fatalistic

acceptance), and partly because the ingredients used in cures were mainly

organic and seasonal, including herbs, other plants, snails and beetles, and

only occasional items produced by anything recognisable as a laboratory

process. (Mercury was an exception, being prescribed for a wide variety

of conditions well into the mid-nineteenth century, though its particularly

vicious side-effects were well known long before that time. Antimony was

also used in various forms as an emetic or purgative.) More complex drugs

contained exotic, imported items such as saffron. Most treatments depended

on location, season and weather as much as on the medical condition of the

patient. Perhaps a signifi cant contrast between rural areas and large towns

was that there was often more in the way of attendant ritual involved with

the administration of Galenical remedies in the remoter parts. An incanta-

tion or superstitious action was often prescribed in conjunction with recipes,

and this was less likely to happen when the same remedies were prescribed

by a qualifi ed physician. The main point, though, is that in terms of everyday

cures, the materials were similar at all levels of society and in most areas.

Among the vast array of plants used were betony (nerve tonic), dandelion

(diuretic, tonic, stimulant), foxglove (heart complaints, scrofula, epilepsy,

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 109FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 109 29/1/10 11:13:5229/1/10 11:13:52

110 Helen M. Dingwall

mental disorders), fumitory (liver and skin problems, leprosy), rue (coughs,

jaundice, rickets, kidney stones) and sorrel (poultices).

4

Care must be taken with the word ‘drug’, though, as modern connota-

tions are rather different. What were prescribed were tonics, emollients,

poultices or concoctions designed to restore humoral balance. They were

general in application, as conditions were believed to originate from general

causes, though they could manifest themselves in local pathology or symp-

toms. Systemic treatments were the norm, even for circumscribed, local

pathology.

A key point to emphasise is the considerable time-lag between new knowl-

edge and its practical application to the extent that everyday life might be

affected. In the broader world of science, the seventeenth century was the

period of Kepler, Bacon, Galileo, Descartes, Boyle, Newton, Hooke and, of

course, William Harvey, whose De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus

(1628) revolutionised medicine – but not immediately. Harvey’s descrip-

tion of the circulation of blood was crucial, but not unopposed in his day.

Similarly, Andreas Vesalius’ anatomical work, De Humani Corporis Fabrica

(1563) began the transformation of surgery – but not immediately.

The Enlightenment period engendered much intellectual debate.

Discussion of this in detail is outwith the scope of this work,

5

but along-

side the towering philosophical and theological intellects were medical men

like William Cullen, who tried to produce new classifi cation systems or

nosologies of diseases (at a time when there was a desire for universal laws

in nature). Cullen’s system was erroneous but at least he attempted to do

it. The fi rst and second of the Alexander Monro triumvirate, who control-

led anatomy teaching at Edinburgh University for much of the eighteenth

century, contributed much to the description of lymphatic, muscular and

nervous systems. In practical terms, the period produced microscopes and

thermometers, but only gradually would these have an impact on the experi-

ence and treatment of pain, illness, disease or accident at any social level.

All of this, together with faster progress in elucidating the functions, or

physiology, of the body by the mid-eighteenth century, would prove crucial

for the future development of medical and surgical treatment, but for the

moment medical practise lagged well behind medical knowledge, and con-

sequently the everyday experience changed but slowly. What also changed

slowly was the general acceptance that the will of God was paramount,

both in the occurrence of disease and its cure. What most people sought

from medical attendants was symptomatic relief – the cure required higher

powers.

There is some merit in viewing the situation in terms of concentric

circles of infl uence and consultation, with Edinburgh (and later Glasgow)

at the epicentre. Within this central core, the experience of illness, disease

and pain – in terms of how they were treated – was perhaps a little more

complex than in the outer circles. Here were the qualifi ed physicians, time-

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 110FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 110 29/1/10 11:13:5229/1/10 11:13:52

Illness, Disease and Pain 111

served surgeons and apothecaries; here would be the early medical schools

and fi rst hospitals; here would be the ‘hotbed’ of Enlightenment discussion;

here would be many of the advances in anatomical knowledge. It was within

this inner sphere that a medical orthodoxy emerged in the early modern

period, centred on the urban medical institutions, which prescribed training

and entry requirements. The identity of Scottish medicine was very much a

hybrid of infl uences, but increasingly what was claimed to be the orthodoxy

was Lowland, urban and ‘professional’, but in medical terms still very much

centred on the humoral tradition.

6

Further out from the centre, but within travelling or correspondence

distance, the experience for some people was relatively similar to that in the

towns, particularly for gentry estates and their households. In the farthest

circles, the balance between qualifi ed and unqualifi ed medical practitioners

was very different, so that as a spectrum of practice, the further from the epi-

centre, the less ‘professional’ was the practice, the less contact possible with

qualifi ed practitioners and the greater reliance on folk and domestic medi-

cine. It was noted by one traveller that there was only one ‘medical man’ for

50 miles north of Aberdeen at the start of the eighteenth century. This was a

Dr Beattie of Garioch, who apparently did his rounds ‘on a shaggy pony’.

7

In

all areas, epidemic or famine intensifi ed the everyday experience of disease.

The situation was a little paradoxical, though, as those who experienced the

new clinical methods pioneered in the hospitals in the second half of the

eighteenth century were generally from lower social levels. The elite did not

consider it socially acceptable to enter a hospital, so in fact the bedrock of

the new clinical medicine was the poor, or at least those who were able to

gain sponsorship to enter a hospital. There was nothing clear-cut about the

everyday experience of un-health in terms of social status or rank.

Professional medicine was exclusively male, but women played a sig-

nifi cant role in the sphere of health and disease. By virtue of their role

in household and family, they were involved in the care of the sick. Elite

women circulated cures around their social circles, in the same way as they

were passed around non-elite society. Veronica, countess of Kincardine,

wrote to the earl of Tweeddale in 1686, requesting information on the ‘dyet

of steel’, as some of her household were ‘much affected w

t

the scurvie’ –

this condition did not spare the elite, and many people consumed scurvy

grass prophylactically.

8

A number of women, perhaps more so in rural

and remoter areas, also acquired the status of wise women: that is, women

who had somehow been given special knowledge, or who could effect cures

for conditions affecting humans or animals. More dangerously, the role of

women as healers and charmers became – in the minds of the politically

powerful at least – subsumed under the general banner of witchcraft, with

tragic consequences for some. This chapter will consider all of these aspects,

focusing on the experience of the people by means of assessing diseases and

their treatment at all social levels and in all areas of the country.

FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 111FOYSTER PAGINATION (M1994).indd 111 29/1/10 11:13:5229/1/10 11:13:52