Fattah H., Caso F. A Brief History Of Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

102

were pillaged, their holdings burned or, as legend had it, thrown in the

river (Elbendary 2003). Altogether, it is speculated by the Indo-Persian

historian Juzjani that up to 800,000 people were killed as a result of the

Mongol sack of Baghdad (Saunders 1971, 231).

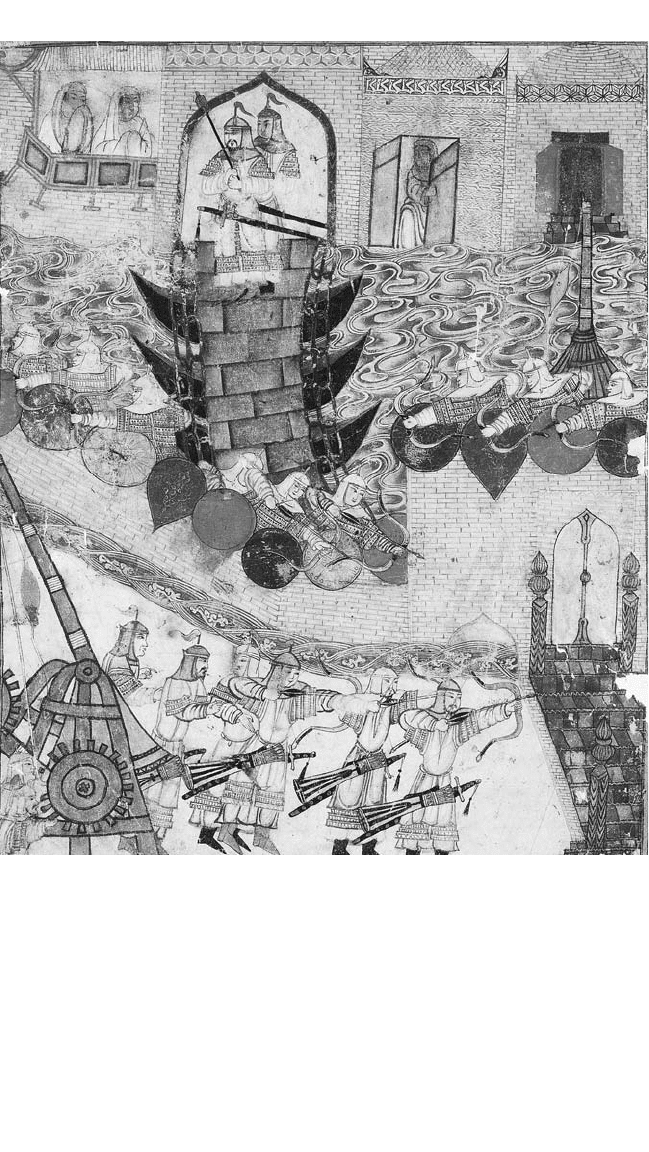

Depiction of the siege of Baghdad in 1258 by the Mongols, led by Hulegu, grandson of

Genghis Khan, which ended the Abbasid caliphate

(Courtesy Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—

Preussischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung)

103

TURKISH TRIBAL MIGRATIONS AND THE EARLY OTTOMAN STATE

Contrary to Islamic historians of the time, modern-day historians

tend to downplay the devastation engendered by the Mongols. A lead-

ing scholar on the Mongols, Wilhelm Barthold, drily observed that,

“the results of the Mongol invasions were less annihilating than is sup-

posed” (quoted in Saunders 1971, 6). However, even though the fi gures

for casualties may have been infl ated by local historians, there is ample

proof for Mongol havoc in other sectors of Iraq’s society. In addition

to the great loss of life as a direct result of the military conquest, the

city population contracted in no small part because of the ruin of its

urban infrastructure, as a result of which many parts of the city became

near desert. Iraq’s great irrigation system was smashed. Channels that

QUESTIONS CONCERNING

THE SACK OF BAGHDAD

H

istorians continue to debate the particulars surrounding the

siege and subsequent sack of Baghdad by Mongol forces in

1258. The Mongol invasion accelerated what had been a gradual

decline of the Abbasid capital. Not until the 20th century would

Baghdad reemerge as an important center in the Middle East. By the

time of the Mongol invasion, the power of the Abbasid caliphate had

been greatly reduced by prior invasion, internal strife, crop failure,

and famine. Yet Baghdad, like Babylon in the days of Alexander, was

seen as the center of culture. Some historians argue that prior to the

Mongol siege, the great khan Mongke had ordered the caliphate be

spared if it submitted to Mongol authority. But historian J. J. Saunders

contends that “the continued existence of a sovereign like the Caliph,

who claimed a vague authority over millions, was an affront to [the

Mongol sky-god] Tengri and the Great Khan, who brooked no rival

on earth” (Saunders 1971, 109). In either case, historians agree on

the caliph’s arrogance and his lack of preparation for the defense of

the city.

Lastly, there is some argument over the amount of destruction.

That it was great, and that the loss of life was uncountable has never

been debated. That the Mongols destroyed the canal system is not

debatable either, but there is contention that toward the end of their

reign, the Abbasids had not kept the canals in good working order.

Also, it is argued that Baghdad’s agriculture continued to suffer in the

wake of the destruction because of soil salination.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

104

had been dug to bring water to the city fell into disrepair, agriculture

declined, and people left once prosperous city quarters to move closer

to the Tigris River, where they could more easily fetch water. Habitation

became confi ned, for the most part, to the eastern part of the capital,

where sanctuary was more abundant. Iraqis were left to forage for food

and water as best they could, their world shattered, their faith sorely

tested (Rauf 2002, 57–67). Interestingly, the legend of the murderous

Mongol persists until today and has so infi ltrated popular memory that

even nowadays, ordinary Arabs and Muslims use it as a yardstick with

which to measure all present-day massacres and catastrophes. Rightly

or wrongly, the U.S. invasion and occupation of Baghdad in April 2003,

which gave rise to days of looting and pillage of museums, libraries,

and government ministries by angry mobs, has been compared to the

destruction of Baghdad under Hulegu the Mongol (Hanley 2003).

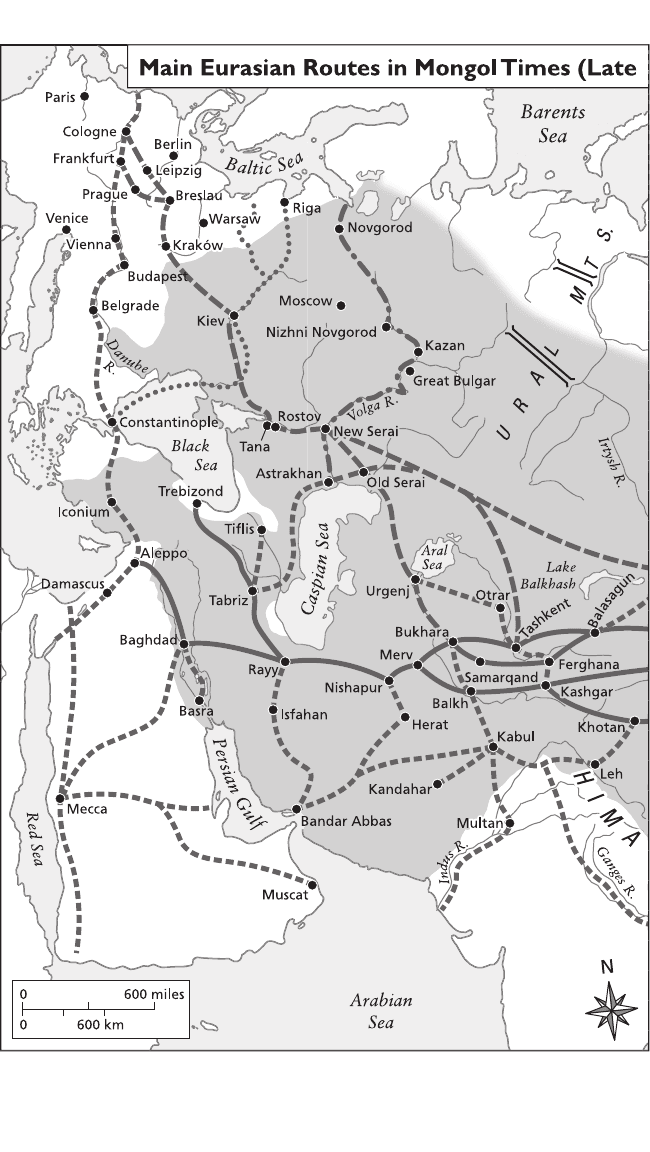

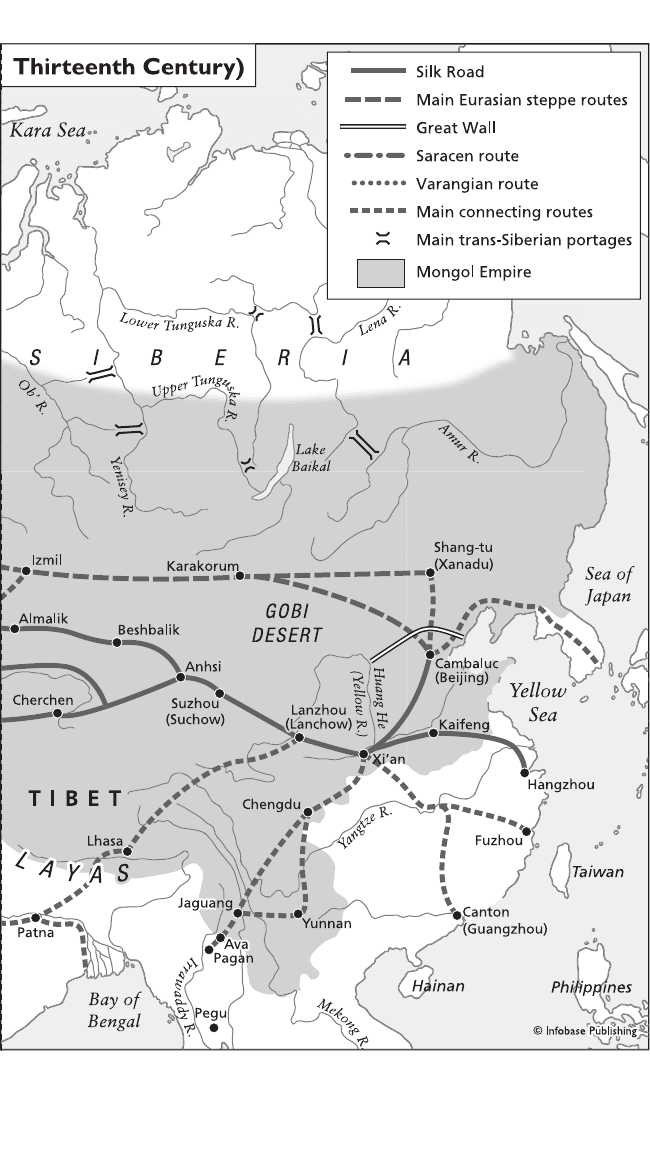

Pax Mongolica and Trade

Janet Abu Lughod has argued that the 13th century witnessed the

rise and eventual demise of a world system based on transcontinen-

tal trade (Abu-Lughod 1989, 3–40). The middle passage consisted of

“the three routes to the east,” namely the northern route passing from

Constantinople (later Istanbul) to Central Asia; the central route con-

necting the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean by means of Baghdad,

Basra, and the Gulf; and the southern route, tying Cairo and Alexandria

to the Red Sea, Arabian Sea, and Indian Ocean. The northern passage

became the monopoly of the Mongols and, later on, the Turkish dynas-

ties that arose in their wake.

According to Abu Lughod, “[T]he thirteenth century Mongols

offered neither strategic crossroads location, unique industrial produc-

tive capacity, nor transport functions to the world economy. Rather,

their contribution was to create an environment that facilitated land

transit with less risk and lower protective rent” (Abu Lughod 1989,

154). The Mongol genius lay in transforming the barren and inhospi-

table wastes of Central Asia into a central trade thoroughfare by means

of the construction of caravansaries (traveler resthouses), warehouses

for merchants’ goods, and armed frontier posts, which greatly contrib-

uted to the overall security of the region. Moreover, “protection” costs,

which entailed paying tribes or transport agents a fl uctuating rate so as

to travel in relative security, were reduced under Mongol administra-

tions. Because the Mongol Empire was unifi ed under one overarching

family system over a large expanse of territory, and because it provided

105

TURKISH TRIBAL MIGRATIONS AND THE EARLY OTTOMAN STATE

a climate favorable to long-distance trade, the northern route attracted

traders from Iran, India, Anatolia, and, eventually, Genoa. In fact, as a

result of European-led voyages of exploration into China (Marco Polo’s

voyage to Cathay in 1260–71 comes to mind), Europeans began to

learn of these mysterious people and to engage with them in a com-

mercial as well as cultural spirit. The great caravan meeting point was

Samarqand, in Central Asia, where traders from India met those coming

from the Islamic lands. The prized commodity that attracted them all

was silk. Chinese silk was so important that it trumped Iranian silk in

Western markets, even though Iran was closer to home and, from an

overall perspective, less unwelcoming terrain than the large expanse of

the Mongol Empire.

The Il-khanids and Timurids (1256–1405)

After the sack of Baghdad, the Il-khanate, a Mongol successor state,

rose to govern both Iraq and Iran, as well as parts of Armenia, Anatolia,

northern India, and Afghanistan. (The title of Il-khan referred to the

state being subordinated to the great khan.) After having kept it at arm’s

length for the duration of a generation, the Il-khanid governors fi nally

submitted to Islam and gave up on their fruitless campaign to promote

Buddhism in the Irano-Islamic region. Under one of their ablest leaders,

Ghazan (r. 1295–1304), the Il-khanids also began to repair the dam-

age wrought by the Mongols’ earlier depredations, rebuilding irrigation

works, reconstructing cities, and opening trade. They made alliances

with the local notability in the region and began to rely on former

administrators for assistance in local government. As security returned,

so did the revival of artistic infl uences and literary and scientifi c inquiry.

The Chinese infl uence in art (especially pottery) became particularly

important in this period. These infl uences included lotus and peony

motifs and depictions of clouds and dragons. In addition, the writing

of history became a critical and well-rewarded endeavor. For instance,

an infl uential Mongol adviser, Ata Malik al-Juvaini (1226–83), who was

the Farsi-speaking author of The History of the World Conqueror (which

depicted the rise and rule of Genghis Khan), was employed as gover-

nor of Baghdad in 1260. Meanwhile, another famous historian, Rashid

al-Din (1247–1318), wrote a compendia of historical works, using a

variety of sources, including Chinese, Indian, European, Muslim, and

Mongol (Lapidus 1988, 279).

The Il-khanids are best remembered for their trade policies, which

made Tabriz (western Iran) one of the most important commercial

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

106

107

TURKISH TRIBAL MIGRATIONS AND THE EARLY OTTOMAN STATE

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

108

capitals of the 13th century. Benefi ting from the Pax Mongolica insti-

tuted in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions, Tabriz became the

center of a trilateral trade network, between the Mediterranean Sea,

the Black Sea, and the Gulf and Arabia. Italian (Genoese and Venetian)

merchants were especially important in Tabriz, exchanging “European

cloth and linen for silk and other eastern wares” (Mathee 1991, 16).

The rise of this commercial center underlined the shift away from

Baghdad and Cairo and the growth of an alternate market in Anatolia

and the Black Sea ports.

In 1336, beset by internal problems and the fact that it was fi ght-

ing on far too many fronts, the Il-khanid state, which had long

broken up into smaller states, saw its vast territories assimilated by

conquest into the growing empire of a Central Asian warrior from

the east, Tamerlane, (Timur; 1336–1405). Although he claimed the

mantle of Genghis Khan, Tamerlane was not, strictly speaking, a

descendant of the Mongol warlord but a Mongol only by marriage.

Nonetheless, he replicated the Mongol system to a fault by embark-

ing on a ferocious campaign of world conquest, invading and occu-

pying Iran, northern India, Anatolia, and northern Syria. Like the

Mongols before him, he again swept into Iraq and destroyed a society

just beginning to recover from the wholesale onslaughts of Hulegu’s

troops 98 years earlier. Unlike Hulegu, however, Tamerlane’s empire

was strictly Muslim, although only formally so. The religious climate

at Tamerlane’s court in Samarqand (now in Uzbekistan) was charac-

terized by the overwhelming contribution of Islamic brotherhoods,

or tariqas, composed of Sufi s (Muslim mystics), who were to wield

far more infl uence over the populace than the more orthodox, sharia-

inspired Muslim clergy.

While Tamerlane followed the Turco-Mongol practice of encourag-

ing long-distance trade with friend and foe, even writing letters to

King Henry IV of England, inviting him to pursue commercial interests

with the Timurid Empire, his invasion of Anatolia and his capture of

the seaport of Izmir in 1402 dealt a death blow to Tabriz’s fortunes

(Knobler 2001, 102–103). The trade of Asia, which had benefi ted from

Mongol protection and encouragement, now suffered as overland mer-

chants, both Asian and European, deserted this newly insecure trade

route and focused on fi nding an alternative route to ship their goods.

At Tamerlane’s death in 1405, just as he was reportedly on the point of

marching on China, the instability of the Timurid Empire had become

evident.

109

TURKISH TRIBAL MIGRATIONS AND THE EARLY OTTOMAN STATE

The Black Sheep and White Sheep Dynasties (1378–1508)

In the post-Timurid period, several Turkmen tribal federations divided

up northern Iraq, Azerbaijan, and eastern Anatolia; among the most

famous were the Ak Koyunlu (White Sheep) and the Kara Koyunlu

(Black Sheep) dynasties. They fought over the pasturelands and farm-

lands of the region from 1378 to 1508. In an era in which legitimacy

depended on a strong patron, intermarriage with Byzantine princesses

cemented the Turkmens’ hold on regional alliances, as did their canny

leadership in times of war. One of the Ak Koyunlu commanders, Uzun

Hassan (r. 1452–78), was even able to rally his tribal armies to cap-

ture Baghdad, southern Iraq, and eastern Iran, in the process creating

a formidable threat to the Ottomans, who had by then grown from a

small Turkish principality founded by Osman I (r. 1281–1326) to an

empire centered on Constantinople, the former Byzantine capital. The

Ottomans were intent on occupying those same districts conquered by

Uzun Hassan, and by 1473, they were able to infl ict a resounding defeat

on the Ak Koyunlu tribes.

The Rise of Osman and the Genesis

of the Ottoman Empire

Cemal Kafadar, a historian of the Ottoman Empire teaching at Harvard,

begins his study of the early empire with these words: “Osman is to the

Ottomans what Romulus is to the Romans, the eponymous founding

fi gure of a remarkably successful political community in a land where

he was not . . . one of the indigenous people” (Kafadar 1995, 1). In

its broad outlines, Kafadar’s statement is true, with the exception that

Osman was not a mythical persona but very much a historic fi gure (a

fact noted by Kafadar elsewhere in his book). Born in 1258, Osman

was one of the many Turkish tribal leaders who settled in Bithynia

(Anatolia), on the constantly fl uctuating frontiers of the Byzantine

Empire. His ancestors had arrived in the region in the second great

mass migration of Turkish nomads from Central Asia. The region was

then a fl uid center of power, characterized by constantly shifting alli-

ances between Turkish nomads, Armenian princes, crusading knights,

and Byzantine generals. Drawn into the no-man’s (or everyman’s) land

on the unstable Byzantine frontier, Turkish warriors skirmished and

sometimes entered into military agreements with a host of adventurers

and interlopers of every conceivable political, religious, and linguistic

stripe. Before the arrival of the Ottomans as an organized political unit,

two large Turkish tribal confederacies held sway: the family group that

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

110

revolved around the legendary warrior Melik Danishmend and the

Seljuks of Rum, a nomadic pastoralist cluster that eventually formed

a state (Rum was yet another term used for the Byzantine, or Eastern

Roman, Empire).

The ghazi state, of which Osman’s was one, was not just a military

formation but a militant one as well. And the militancy of that state

rested upon its Islamic component, which itself was an amalgam of

the shamanistic and spiritualist vestiges of a Turkic nomadic past with

the holy war tradition in Islam. Ghazis were, for the most part, warrior

Sufi s who raided the lands of dar al-harb (“the abode of war,” the name

given by Muslims to non-Muslim districts), in the process opening up

the Byzantine-Anatolian borderlands to Islam. It was the ghazi ethos

that was to shape Ottoman societies from the very beginning, in its

insistence on “a dynamic conquests policy, basic military structure and

the predominance of the military class within an empire that success-

fully accommodated disparate religious, cultural and ethnic elements”

(Inalcik and Quataert 1994, 11). Osman’s state was only one of the many

contending polities that struggled for ascendancy in that period, but

his state-building venture was to outshine and outlast all the polities

that had existed before. According to tradition, in 1299, Osman, taking

advantage of a perceived power vacuum in Anatolia, declared his princi-

pality’s independence from the Seljuk Turks, who, in any case, ruled the

area for only eight more years. This tradition has it that Osman’s declara-

tion of independence is the beginning of the Ottoman Empire.

An exceptional commander and an even better administrator, Osman’s

chieftaincy became an enduring state only gradually. In 1326, just prior

to Osman’s death, the Ottomans, led by Osman’s son Orhan, captured

Bursa (located in what is now northwestern Turkey) from the Byzantine

Empire and made it their capital. After Orhan (r. 1326–62) succeeded

his father as bey, he named his brother Alaeddin as vizier, the ruler’s

most trusted adviser. In 1328, Orhan began a three-year siege of Nicaea

(modern Iznik) that ended with that city’s surrender in 1331. The cap-

ture of Nicomedia (modern Izmit) in 1337 and the defeat of the princi-

pality of Karasi placed all of northwestern Anatolia in Ottoman hands.

Together Orhan, who was the fi rst Ottoman to bear the title of sultan,

and Alaeddin forged the basis of the empire. Instead of simply conquer-

ing and moving on as had many of their predecessors, the Ottomans

worked to assimilate conquered territory into their (Anatolian) empire.

This period of consolidation was aided by Ottoman-Byzantine peace

for approximately 20 years and by the marriage of Orhan to Theodora,

111

TURKISH TRIBAL MIGRATIONS AND THE EARLY OTTOMAN STATE

daughter of Byzantine emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–54),

whom Orhan had assisted in gaining the throne.

Orhan was succeeded by his son Murad I (r. 1362–89). During

Murad’s reign, the Ottoman Empire, with the assistance of the ghazi

warriors and using Gallipoli as a base, expanded into Byzantine terri-

tory, making vast inroads in northern Greece, Macedonia, and Bulgaria

which bypassing Constantinople. Murad’s administration of the con-

quered European territory differed from his father’s Anatolian plan of

assimilation but nevertheless proved successful, as the Ottomans main-

tained suzerainty over their European vassal states.

However, after these impressive gains of the Ottoman state in the

Balkans and Anatolia, Bayezid (r. 1389–1402), Murad’s successor, was

defeated in 1402 at Ankara by Tamerlane, who then turned eastward to

resume his conquest of India. His excursion into Anatolia was to restore

the Turkish princes, including some Ottomans, to their thrones, thus

dividing Anatolia and making it less likely to pose a threat on his own

western fl ank. In this, Tamerlane was temporarily successful.

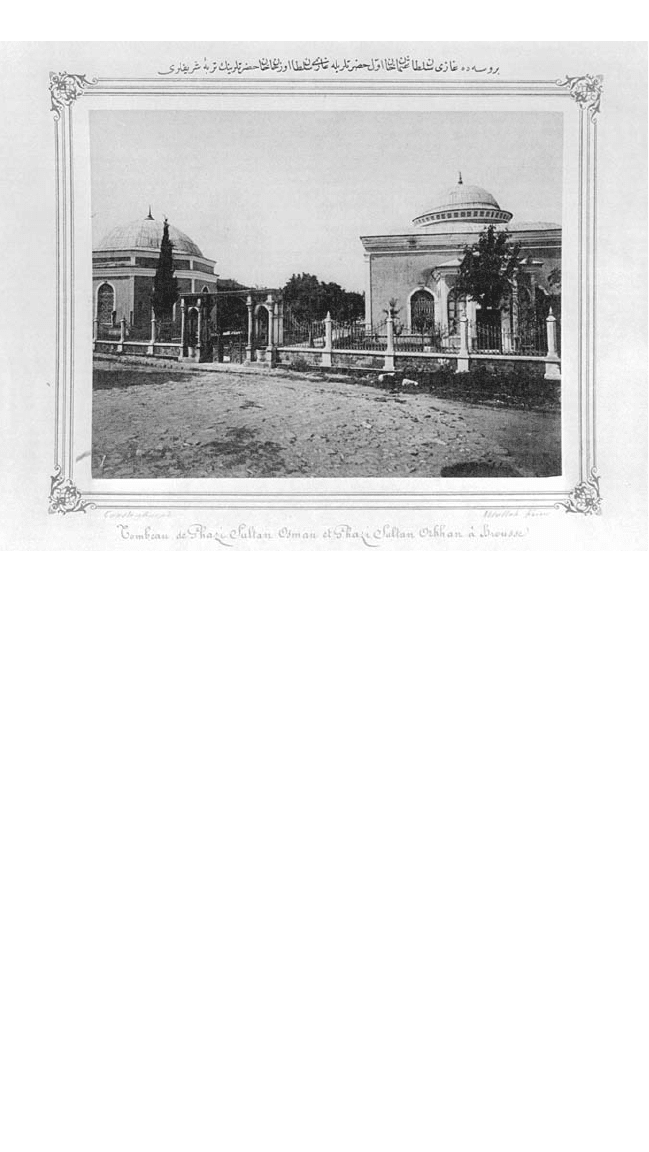

The mausoleums of Osman I, for whom the Ottoman Empire was named, and his son Orhan

at Bursa in northwestern Turkey

(Library of Congress)