Fattah H., Caso F. A Brief History Of Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

82

considerations, mutinies and rebellions rumbled on, particularly those

mounted by religious-political parties, such as the Khawarij and Shia.

By the beginning of the ninth century, and as a result of the vicious civil

war between two sons of the fi fth caliph, Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809),

al-Mamun and al-Amin, the caliphate had become a shell of its former

self, relying almost totally on foreign councillors and armies and facing

prolonged revolts against central authority.

Trade and Agriculture under the Abbasids

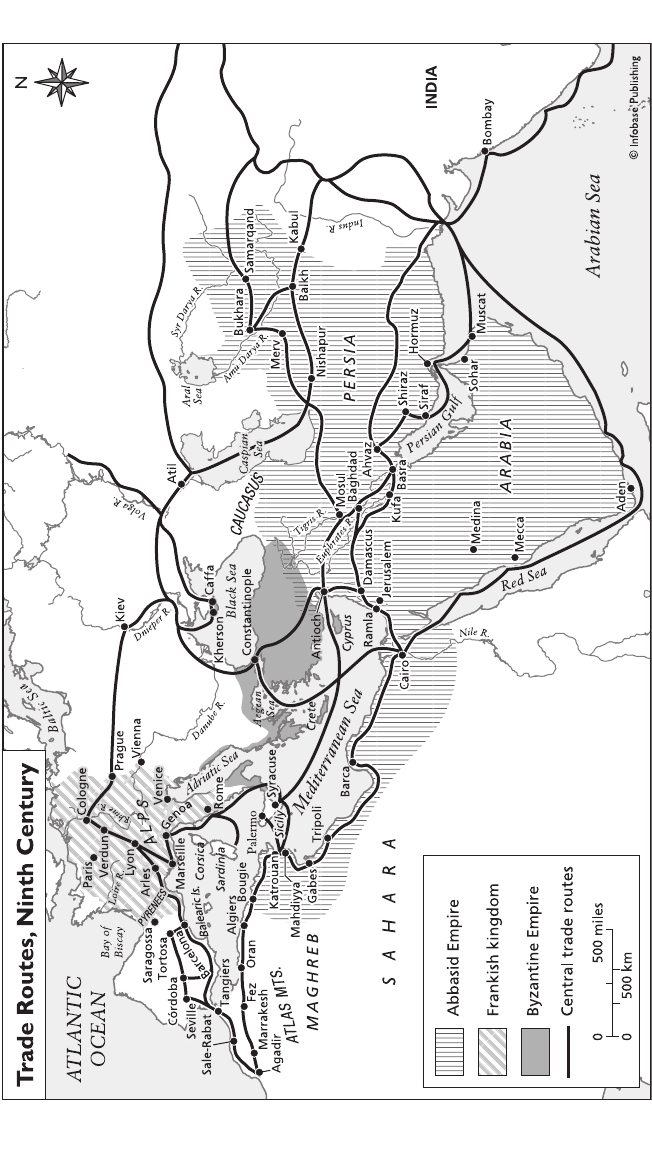

Prior to the civil war, during the reign of al-Rashid, Abbasid prosperity

reached such heights that the real motors of imperial expansion may

not have been as much military and political in nature as they were

economic. Starting from the late eighth century onward, trade and

agriculture connected the empire with the entire known world through

networks of land and sea routes. By the 13th century, it is estimated

that empire-wide trade had become the vital linchpin of a world system,

tying the eastern Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean and both of them

to China. The Abbasid Empire, a key player in world trade, was at the

heart of this world system, if not its chief conduit, as Muslim, Christian,

and Jewish merchants operating under its patronage bartered, bought,

and used credit to ship textiles, food products, and livestock all over the

empire and far beyond. Among the fi rst items to be traded were wood,

metal, sugar, and paper.

One of the chief reasons for the effi ciency and success of long-

distance trade, whether by land or sea, was the unity imposed by

Islamic rule. That unity was established from the very fi rst outpour-

ing of Muslim troops into the fertile and cultivable lands of the East

Mediterranean and North Africa. Later on, Umayyad and then Abbasid

control of the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean created a clearly

defi ned and homogeneous area for transempire trade, unifi ed by

Islamic customs and mores and tied by the Arabic language. However,

historians have pointed out that while the Abbasid Empire at its height

controlled a large proportion of the known world, there were at least

two other economic zones that cooperated as well as came into confl ict

with the Muslim realm, and those were China and the yet-to-be unifi ed

and largely underdeveloped European states.

Sociologist Janet Abu Lughod has written that there were striking

similarities between economic systems in Asia, the Islamic world, and

the West, and that contrary to the belief that capitalism or a money-

driven economy only developed in Europe, both the Islamic empire

83

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

84

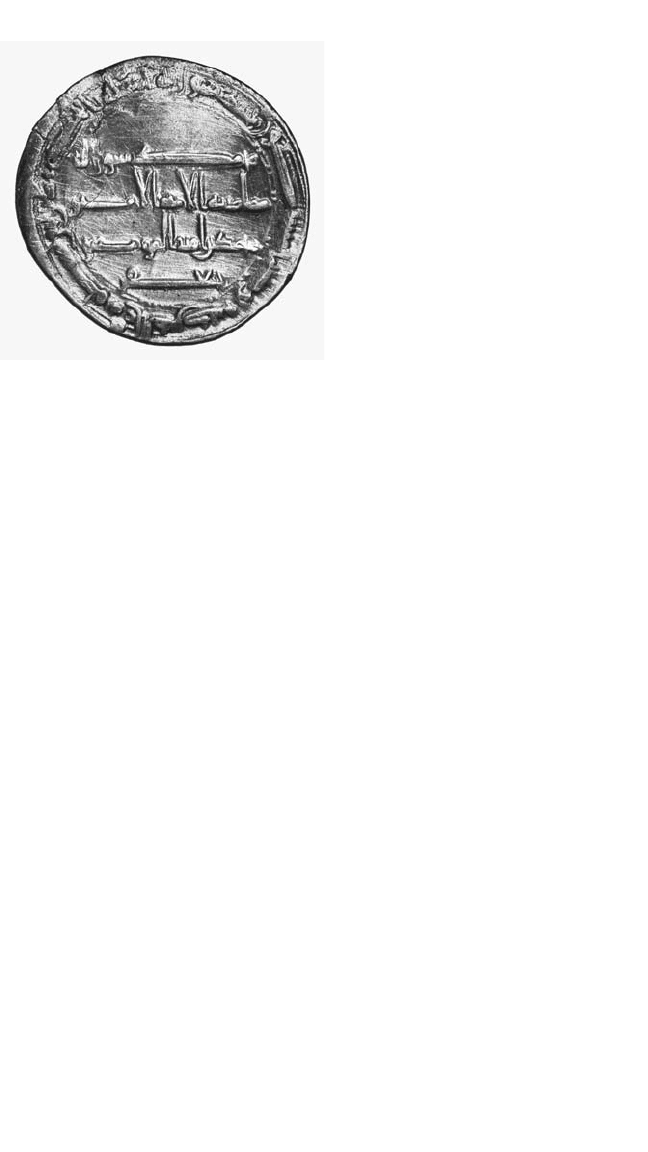

and China had created capi-

tal-intensive economies that

competed fairly well with each

other (Abu Lughod 1989, 15–

18). The Abbasids and, later

on, the Italian merchant city-

states minted coins in their

rulers’ names; in China, paper

money was introduced in the

early ninth century. Credit was

widely available so that trad-

ers could buy in one place and

guarantee payment in another.

Banking appeared initially in

the Islamic world and was

later copied by Europeans:

members of merchant families

worked for family fi rms in disparate regions of the world and guaran-

teed long-term credit and cash payments in a premodern system of fam-

ily banking. As a result, Muslim traders were able to establish trading

posts as far away as India, the Philippines, Malaya, the East Indies, and

China. Abu Lughod also shows that even in small Islamic city-states,

there was a controlling oligarchy at the head that monopolized trade

and organized traders.

According to historian K. N. Chaudhuri, there were four great Asian

commodities bought and exchanged in medieval times: silk, porcelain,

sandalwood, and black pepper (Chaudhuri 1985, 39). Other products

complemented transregional trade, such as shipments of horses from

the Gulf; incense from southern Arabia; and ivory, cloth, and metal.

There were many important port cities that facilitated this regional

trade. Until the advent of the Abbasid Empire, trade was mostly land

based and carried out by camel caravans passing from ports such as

Jeddah (western Arabia) to Egypt and Yemen. After the conquest of

the eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, Abbasid merchants

were able to use the sea to great effect. New port towns developed or,

in some cases, were redeveloped from small coastal communities to

large trading emporia. For instance, Basra in southern Iraq, although

built as a garrison town for Islamic troops, quickly became a major

trans-shipment route for goods from Syria, Baghdad, and the coastal

Gulf islands to India. Until the 20th century, Basra remained the main

port of shipment to Bombay (present-day Mumbai) and other cities in

An Abbasid-era dirham, the unit of currency,

from Baghdad ca. 786–809

(Kenneth V.

Pilon/Shutterstock)

85

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

western India. Other famous commercial centers in the Abbasid era

were Siraf, a short distance away from Basra on the Persian side of the

Gulf, Hormuz at the tip, Sohar in Oman, and Aden in Yemen. There

were also the famous East African ports of Kilwa and Mombasa, from

which sailors traveled across the Indian Ocean in ships that had been

constructed without the use of a single nail.

Cultural and Intellectual Developments

The political and socioeconomic achievements of the Abbasid state were

accompanied by riveting developments in the spread of human knowl-

edge and the growth of the sciences, which came to be seen as the deter-

mining features of the far-fl ung Abbasid Empire. The sophistication of

its literate elites, the mass appeal of its educational establishments, the

systematization of its legal and societal structures, and the receptivity to

the world are what underpinned the true Abbasid revolution.

The Question of Legitimacy

From 759 to 874, among the thorniest issues bedeviling the Abbasid

caliphate was its relationship with the two main strains in Islam,

Sunnism and Shiism. By the eighth century, the split between both

had led to several wars, or fi tnas, as well as polemical and doctrinal

arguments, which were later to be incorporated in each community’s

traditions and bequeathed to later generations. At this initial stage,

those religious-political currents had not yet gelled into hard-and-fast

ideologies; they were more or less rival interpretations of certain crucial

events in early Islam (such as the succession question or the issue of

salvation) that, while inspiring political revolts throughout the empire,

were not yet adequately supported by a systematic body of doctrine.

The Abbasids came to power promoting what was essentially a Shii

message: They emphasized revenge for the death of the Prophet’s grand-

son Husayn, who had been killed in piteous circumstances by Yazid, the

son of the fi rst Umayyad caliph, Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan. The problem

for the early Abbasids, however, lay in the fact that by propagating the

martyrdom of Husayn, they were helping to endorse the legitimacy of

the family of Ali ibn Abu Talib, the father of Husayn and son-in-law

of the Prophet. The Alids, as some Western scholars call the family of

the imam Ali (in Arabic, the Alids are referred to as Al al-Bayt, or the

Family of the House of the Prophet), were revered by the Khurasanis

and other Muslim settlers in the eastern parts of the empire, who fully

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

86

expected an Alid descendant to become imam, or ruler, of the new

Abbasid Empire.

The Abbasids were therefore involved in an ideological struggle with

the Alids from the very beginning, with the Abbasids attempting to but-

tress their claim to be the most legitimate of the Prophet’s descendants

in a variety of ways. One surefi re method was to maintain, on the basis

of assorted hadith, or sayings of the Prophet or his Companions, that

“the Prophet had a special regard for the Abbasids’ ancestor al-Abbas

and [to encourage] various prophecies foretelling the Abbasid acces-

sion” (Buckley 2002, 135). Because these claims did not prove legiti-

macy to the Alids and the substantial majority was in favor of the Alids,

the second Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur, eventually had two pro-Alids,

Abu Salama and Abu Muslim, the celebrated leader of the Abbasid

revolt, executed.

Meanwhile, al-Mansur’s shaky relationship with the imam Jaafar al-

Sadiq, the sixth imam (descendant of the House of the Prophet through

Ali and the charismatic leader of the Shia community), grew shakier

as the years went on. Finally, on December 4, 765, Jaafar al-Sadiq died

under suspicious circumstances in Medina, widely thought by his fol-

lowers to have been poisoned by the caliph.

Jaafar al-Sadiq is a very important fi gure in Shii lore because it was

he who formulated the doctrine of the imamate, that is, the notion of

the charismatic leader who would lead the Shii community in times

of travail. After his death, the Alid, or Shii, party split over the iden-

tity of the Mahdi, a messianic belief in a savior who will reappear on

earth to bring social justice. One faction believed that al-Sadiq was the

Mahdi, whereas another group forwarded Jaafar’s son Musa al-Kazim

as a candidate for the role of the Mahdi. Yet a third group proclaimed

two other descendants of Jaafar al-Sadiq, his son Ismail, who died in

760 fi ve years before Jaafar, and then Ismail’s son Muhammad as the

Awaited Ones. However, it was only in 874 that the three Shii fac-

tions crystallized into different, defi nitive schools of thought to which

the preponderant majority of Shiis adhere until the present day. After

the death of the 11th imam without an heir, the theory of the Greater

Occultation (ghayba) was developed, which stressed that the hidden

12th imam was not dead but in seclusion until the time when he was to

reappear as Mahdi to rescue his fl ock. The two schools of thought most

associated with this philosophy were the Twelvers (ithna ashariyun, in

Arabic; so called because they believed that it was the 12th imam who

disappeared) and the Ismailis who believed that it was Jaafar al-Sadiq’s

son Ismail who was to return as the Mahdi. The third school of thought,

87

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

Zaydism, was not as widely subscribed to; therefore, it posed lesser

problems to the Abbasids.

The dilemma posed to the Abbasid caliphs by the growing Shii

movement thus involved not only legitimacy or ideological “cover”

for an increasingly secular state but, worse, the persistence of political

claims to the leadership of the Muslim community that the Abbasids

believed settled with their accession to power. To control the imamate,

the caliph al-Mamun even tried to bring it within the direct orbit of the

caliphate by designating Musa al-Kazim’s son Ali al-Ridha as his suc-

cessor, only to witness his death a few years later, in 817. Suffi ce it to

say that until the end of their caliphate, no real solution was found by

the Abbasids to the Shii challenge, which continued as an underground

tradition throughout the major part of the Abbasid era.

Sunni Law and the Development of Sufi sm

By the middle of the ninth century, a similar process of self-defi nition

was taking place in what was soon to be called the Sunni community.

The evolving Sunni consensus centered on the study of the Qur’an

and Hadith and the developing system of fi qh, or the inferences and

precedents of Islamic law. The latter was used most often in matters of

personal or family status, such as marriages, divorces, and inheritance.

The creation of Sunni law was the work of a professional elite of reli-

gious scholars and professors of law and theology, but the legal system

also developed as a result of strong Abbasid support. Nevertheless, just

as Shiism had developed splits in religious interpretation and political

alignments, so too, at times, did Sunnism.

One of the largest differences between Muslims as a whole concerned

the path to salvation. In Sunni Islam, in particular, this took two forms:

a literal and prescriptive reading of the Qur’an and sunna, which led to

the formulation of the principles of Islamic law, or sharia; and a mysti-

cal, transcendent, deeply individual interpretation of Islam’s holy book

called Sufi sm. From the dawn of Islam, there were two types of men:

those who read the Qur’an and Hadith in order to draw out from them

an orderly, rational, legal structure and those who read the Qur’an in

order to grasp its immediacy and power. The fi rst, the ulama, became

the leaders of the Sunni religious community; the second, the mystics,

were the traveling men of God who searched for an experience of the

divine that was not bound by cold, formal logic. The mystics, or sufi s,

in Arabic, believed that they could experience a direct union with God

through the pursuit of rigid self-discipline, poverty, spirituality, and the

renunciation of human desire, and that, rather than subscribe to the

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

88

literal meaning of the Qur’an, the true Sufi could arrive at a deeper,

more allegorical meaning of God’s unity through a closer and more

emotive reading.

By the early 10th century, Sufi brotherhoods were beginning to initi-

ate followers in the way, or tariqa, by which they could directly experi-

ence God’s Oneness. The late scholar Albert Hourani continues with

the story:

There was a process of initiation into an order: the taking of an

oath of allegiance to the shaykh, the receiving from him of a

special cloak, the communication by him of a secret prayer . . .

the central act of the tariqa and the characteristic that marked

it off from others [was] the dhikr or repetition of the name of

God, with the intention of turning the soul away from all the

distractions of the world and freeing it for the flight towards

union with Him (Hourani 1991, 154–155).

However, after some time, Sufi sm, with its more esoteric knowledge

of the divine, began to create enemies among the more orthodox Sunni

scholarly establishment, and a serious rift developed between the ulama

and the mystics of Islam. This rift was only resolved by the great Islamic

scholar al-Ghazali (1058–1111), whose synthesis of Islamic learning won

over both the Abbasid ruler of the time and the more disaffected schol-

arly circles in the empire. In various texts, al-Ghazali set out his treatise

that “Muslims should observe the laws derived from the Will of God as

expressed in Quran and Hadith . . . to abandon them was to be lost in a

world of undirected human will and speculation” (Hourani 1991, 168).

The Islamic Sciences and the Translation Movement

Unlike scientifi c inquiry in the West, what fell under the rubric of the

Islamic sciences (alchemy, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and so

on) grew out of a religious outlook and was not “secularized” until the

19th century. From the very fi rst, scientifi c investigation was perme-

ated by the ideas of God, nature, and the universe. The essential doc-

trine of unity—that there is no God but God, and Muhammad is his

Messenger—allowed Muslims to conceive of all creation as God given

so that any endeavor to understand the principles of the natural world

was to be, fi rst and foremost, an exercise in understanding the beliefs

and directives of Islam. For instance, astronomy became a key sub-

ject under the Abbasids because the marvels of the universe occupied

much of the Qur’an. Meanwhile, geography originally grew out of the

Qur’anic concentration on nature. Finally, because of the attentiveness

89

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

given in Islam to studying the unity of humans and their surround-

ings, the Islamic sciences were, by their very nature, comprehensive

and meant to embody universal lessons, useful primarily because they

reconciled religion with the world. As a result of this philosophy of

knowledge, the Arab scientist’s greatest aim was to be a generalist in

all things; in the larger sense of the term, this meant that while he may

have been best known for his pioneering studies in astronomy or medi-

cine, he could also combine the specialties of music, literature, and

mathematics. Much like the famous universalists of the 14th-century

European Renaissance, who were directly infl uenced by Arab-Muslim

translations of Greek philosophy and science, the Muslim scholar in

Abbasid times aspired to be well versed in every type of cultural and

intellectual discipline.

From the ninth to 13th centuries, the Abbasids and their successors

patronized a scientifi c and literary movement that had few parallels in

history. The genuine scientifi c interest of some of the reigning caliphs

in Baghdad as well as the independent inquiry of a number of brilliant

scholars in the city and throughout the empire, coalesced in a vast trans-

lation movement that created the momentum for further research and

discovery. In the early ninth century, the caliph al-Mamun established

the research university Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad,

which spurred on the translation of many Greek, Sanskrit, and Old

Persian manuscripts into the Arabic language. Bayt al-Hikma’s library

was only one of the 36 libraries built in Baghdad; much later on, the

library at the famous al-Mustansiriya University (dating from around

1227) was to grow to include 80,000 books. Meanwhile, schools of

astronomy and medicine were founded; and teaching hospitals such as

the Bamiristan al-Adadi in west Baghdad were instituted. There, a cadre

of doctors watched over a stream of patients and compiled meticulous

records, which, in the case of the celebrated physician Abu Bakr al-Razi

(d. 932) served as invaluable research for his world-famous medical

encyclopedia, al-Hawi (Inati 2004, 39). Some of these great universi-

ties, including the Mustansiriya and al-Nizamiyya (11th century) in

Baghdad, were created decades before European institutes of higher

learning were even thought of.

Among scholars of Baghdad, the great Arab philosopher, mathemati-

cian, astronomer, and musical theorist al-Kindi (d. 873) was employed

by al-Mutasim and tutored the caliph’s son. Because astronomy was

much in favor at the caliph’s court, Baghdad was the seat of numer-

ous observatories, the most famous of which was built by al-Mamun.

Al-Khwarizmi (d. 847) concerned himself with the study of “celestial

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

90

objects” (Inati 2004, 40), pioneering the use of the astrolabe, an instru-

ment designed to measure the positions of the stars in the sky. Other

great names in Islamic philosophy such as al-Farabi (873–950), who

wrote al-Madina al-Fadila (The Ideas of the Citizens of the Virtuous City),

and Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West; 980–1037), came from

This 13th-century miniature by Maqama of Hadjr-al-Yamana, located at the Institute of

Oriental Studies in St. Petersburg, Russia, depicts a physician drawing blood. Islamic science

fi rst blossomed under the Abbasids.

(Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

91

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

afar to make Baghdad their second home. Ibn Sina’s thinking, in par-

ticular, exerted great infl uence on Islamic culture.

Abbasid culture and science was the result of a multicultural society.

For instance, the Christian contributions to Islamic science have been

noted in different ways. On one level, a steady stream of Christian phi-

losophers and scientists made an active contribution to world culture

by translating Greek texts into Arabic, and under Abbasid patrons such

as Caliph al-Mamun in Baghdad, they wrote a great many medical and

technical compilations of their own. On the other, in monastic com-

munities in eighth-century Abbasid-era Palestine, monks began writing

ecclesiastical histories, not in Syriac or Aramaic, languages of the Bible,

but in Arabic. It may well be that the use of Arabic was a conscious

decision on the part of the monastic translation movement to spread its

liturgical and theological principles to regions distant from Palestine-

Syria (Griffi th 1999, 25–28). Whatever the reason, Syriac scholar

Sidney Griffi th has shown that even the strictest Christian authors were

so immersed in Arab culture that they had a tendency to use the Arabic

of the Qur’an in their general correspondence.

Samarra and the Creation of a Turkish Army

The death of al-Mamun in Tarsus and the accession to the caliphate

of his half brother, al-Mutasim (r. ca. 834–847), marked a change in

attitude between the caliph and his subjects, particularly the citizens

of Baghdad, that is signifi ed by the building of Samarra. The traditional

explanation for the creation of Samarra is that al-Mutasim, whose own

mother was a Turk, felt uncomfortable in Baghdad. Both he and his

Turkish troops were seen as unwelcome in that city, having been domi-

nated for so long by his more forceful half brother, al-Mamun. Whatever

the reasons—and they must have been many to leave a capital city so

well entrenched in Abbasid tradition—al-Mutasim decided to move out

of Baghdad (which remained the cultural and commercial capital) into

a newly established city further north, called Samarra. Samarra’s name

is usually seen as a play on the Arabic words surra ma raa (pleased is he

who sees it), and al-Mutasim’s city fulfi lled that expectation very well.

It was extremely large, spectacular in terms of architectural design, and

took several decades to complete (Robinson 2001, 9–20). The building

of the city drew on exorbitant sums from the Abbasid treasury, but it

was to last as a breakaway capital only until 892, somewhat less than

60 years. Still, its very establishment was indicative of important trends

that were to manifest themselves throughout the century.