Fattah H., Caso F. A Brief History Of Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

72

disparate teachings of various Shia jurisprudents and community lead-

ers into a doctrine of the imamate, the chief Shia institution.

Iraq Under the Umayyad Empire

Of the four Rightly Guided Caliphs, three died through assassination;

only Abu Bakr, the fi rst khalifa, died a natural death. Besides the violent

blows directed against the leadership of the umma after the Prophet’s

death, there were other, equally fi erce struggles for power that drove a

wedge between Muslims and embittered relations between them.

For instance, problems quickly developed as a result of the dis-

tinctions made between Arab and non-Arab Muslims. Particularly in

Iraq, how did cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity give way to

the adherence to one religion, Islam, and one language, Arabic? The

process of Islamization was so gradual that most historians date the

beginning of mass-scale conversions only to the 10th or 11th centuries.

Because Muslim administrators initially categorized their subjects into

Arab Muslims and mawali and discouraged large-scale conversions to

Islam for fear of losing their exclusive status, the process of adaptation

to the new faith was deliberately slow. The mawali deemed this unfair

and complained, with some justifi cation, that they risked their lives

every day for the Islamic cause and yet were still seen as second-class

Muslims. Those mawali were to be found, for the most part, in Iraq and

the eastern parts of the Islamic empire, particularly in Khurasan, where

resentment at their treatment by the Arab elite soon developed into a

political platform.

Schismatic movements and political discord were not all that hap-

pened in the fi rst couple of centuries of Islam. Much larger and far

more signifi cant developments took place that testifi ed to the grow-

ing linkages between groups and classes from Medina to Herat. Solid

advances were made in theology, law, the economy, culture, and poli-

tics that transformed the lives of many Muslims as they went from a

partly nomadic society to a multilingual, multiethnic, and progressively

inclusive empire. Under the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus, the Arabs

in Iraq and many of the newly conquered regions of the Islamic empire

saw a slow but steady diffusion of Persian administrative traditions that

transformed the caliphate; fi nancial organization, such as an early form

of banking; agricultural expertise, such as canal building and irrigation

at which the people of Mesopotamia excelled; and cultural practices,

in part inherited from Sassanian and Hellenistic sources, in part native

born, experimental, and often brash. Although the Arab military elite

73

IRAQ UNDER THE UMAYYAD DYNASTY

had marched into Iraq (and Iran, Syria, Afghanistan, and North Africa

as well) determined to hold on to their language and customs, even-

tually even the most unyielding let down their guard and began to

assimilate into the more developed urbanity of the land between the

two rivers and its rich and polyglot culture.

Very early on, then, and despite the political and military turmoil all

around them, the Muslims of Iraq, whether new or late converts, settled

down to make sense of their new surroundings and to participate in

the building of their new society. And because the Qur’an, the revered

and holy book for all Muslims, had made such an immediate impact on

their lives, it was natural that the fi rst literate communities would try

to draw lessons from it and generalize those lessons into standards by

which to judge the new state and society that had emerged in Islam’s

wake. In Basra and Kufa in Iraq, as well as in other towns across the

empire, men, young and old, began to discuss and debate the structure

of the Arabic language, poetry, law, Islamic mysticism, theology, and

history. Whereas the population of the new settlements fused tribal and

pre-Islamic oral tradition with the new emphasis on Qur’anic interpre-

tation and recitation, state leaders in Medina and later on, in Damascus,

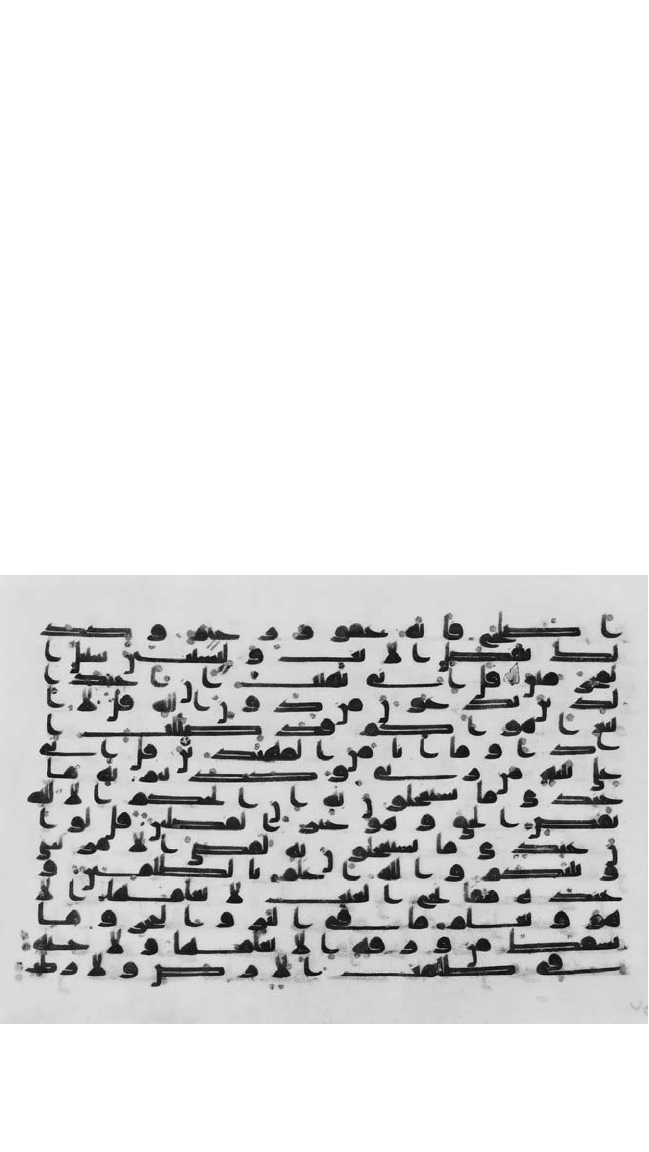

Detail of an eighth- or ninth-century Qur’an written in Kufi c script, which fused with tribal

and pre-Islamic oral tradition in the newer settlements of Iraq during the nascent Islamic

period

(Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Art Resource, NY)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

74

created a courtly literature that integrated Arab motifs with Sassanian

or Byzantine authority symbols. Such, for instance, was the practice of

addressing the caliph as khalifat allah (the deputy of God), which was

unheard of in the early Islamic period (Lapidus 1988, 85).

In mid-eighth century Basra, a whole school of thought evolved

based on grammar, lexicography, and the hermeneutics of the Arabic

language. While recording the oral poetry of the nomadic and half-

settled tribes of Arabia, the scholars of Basra and Kufa also began to

collect the oral histories of the men who had known the Prophet and

the elders of mid-seventh century Arabia. Eventually that lore, scrupu-

lously checked and rechecked through hundreds of interviews, formed

the basis for the compilation of the Prophet’s sayings in the Hadith (al-

ahadith al-nabawiyya), which is the second source, after the Qur’an, to

be used by Muslims as a guide to live the exemplary life, modeled after

that of the Prophet’s.

Meanwhile, in the eighth century, Persian-infl uenced ideas of abso-

lute monarchy, social hierarchy, and rigid class structure began to

permeate the way that Arab caliphs saw themselves, and principles of

a rough egalitarianism began to give way to notions of imperial autoc-

racy. In this period, too, Persian literature, Sanskrit religious texts, and

translations from Greek of works by authors such as Aristotle, Plato,

Galen, and Hippocrates began to transform the Arabs’ ideas of the

world. Various philological schools, located mainly in Baghdad but also

in other cultural centers such as Basra, gained scholarly acceptance

so that by the mid-ninth century, “the output of the translators was

prodigious, and the editors achieved excellence in the preparation of

accurate and reliable editions” (Lapidus 1988, 94). Geographers and

astronomers sought to retrace the footsteps of the ancients and discover

the principles of the universe.

Eventually, schools of law were established, in which the sharia, or

law derived from the Qur’an and Hadith, gained ground and in due

course began to infl uence both state and society. These schools of law,

fl uid as they were in their composition and their teachings, began to

formulate the beginnings of a Sunni position on everything from fam-

ily law to the nature of authority. Meanwhile, at the very same moment

that the religion of Islam was being interpreted and codifi ed by groups

of pious Muslims in the new settlements, the state was starting to use it

as an instrument of legitimization and imperial authority. In fact, even

during the period of the Umayyad state (which came to an end in 750),

religion, theology, philosophy, and law became the battleground for

different interpretations, with the caliphs attempting to gain primacy

75

IRAQ UNDER THE UMAYYAD DYNASTY

over religious scholars by means of imperial fi at. Conversely, as Lapidus

notes, the “Umayyads also sponsored formal debates among Muslims

and Christians which led to the absorption of Hellenistic concepts into

Muslim theology” (Lapidus 1988, 82). While the struggle over who

was to be the custodian of Islam came to a peak much later, during the

Abbasid period, it is important here to underline the tensions between

the centralizing Umayyad state in Damascus and the scholars of law

and theology that largely lived in Kufa and Basra in Iraq.

Conclusion

Iraq’s history throughout the seventh and up to the mid-eighth centuries

was one of rapid conquest, a more or less orderly transition from tribal

encampment to urban heterogeneity, and the adaptation of Muslims to

the diversity of the Iraqi experience. If there is a central thread of Iraqi

history in this period, however, it is the spillover of intellectual thought

into political activity and the creation in Iraq of zones of contention

and disputation in which local groups such as the pro-Ali Shia parties

centered in Kufa (and later, Karbala); the new solidarity among Sunni

Qur’an readers and reciters in both Kufa and Basra; the claimants to the

caliphate converged in Basra; and the Khawarij, who were everywhere,

created the fi rst Islamic communities separate from the state. The lat-

ter, in its Umayyad incarnation, mounted several military campaigns to

do battle against those heterodox elements but could not completely

wipe out the most radical among them. Iraq was to remain a political

tinderbox throughout the Umayyad period and for many decades to

come after that.

76

4

ABBASID AND

POST-ABBASID IRAQ

(750–1258)

T

he Abbasid dynasty began surreptitiously as an underground revolt

in the far-away province of Khurasan, a region between Iran and

Afghanistan and continued until it had amassed enough men and arms

to overthrow the entire Umayyad ruling family in Damascus bar one,

the famous Abdul-Rahman who made his way to Spain and eventually

installed a dynasty of his own. Like the Alids, the descendants of Ali,

who was the last of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, the Abbasids were

descended from an uncle of Muhammad, al-Abbas. However, “their

immediate claim to the Caliphate rested upon the allegation that a

great-grandson of Ali, Abu Hashim, had bequeathed them leadership of

the family” (Lapidus 1988, 65). The Abbasids were supported by Abu

Muslim (728–755), a brilliant strategist who soon became the leader

of the revolution in all but name. They also drew on the support of

the mawali (the non-Arab Muslim “client” population in the Islamic

empire). Although the old landed Iranian aristocracy had assimilated

quickly in Khurasan and lands further east, the Iranian converts were

still discriminated against and had to form patron-client relationships

with Arab tribes in order to achieve some form of parity in the new

society. Many came to believe that their status as second-class citizens

was unfair and utterly unworthy of the Islamic ideology of the empire.

Joined to those grievances were those of the former Arab warrior class,

“who had been promised tax reform by the Umayyads and had been

betrayed” (Lapidus 1988, 76). They had become settled farmers in

Khurasan; burdened by taxes and yet denied relief, they took up arms

against the Umayyad in a last-ditch effort to strike a better bargain for

themselves and their families.

77

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

The Abbasid revolution has gone down in history as one of the best-

organized rebellions in the annals of early Islam and one that was of

central importance to the reorientation of the Islamic empire to the

east, Iran in particular. In the latter stages of the campaign, eschato-

logical prophecies were reproduced to announce the coming of the

impending revolution, and black banners, which had already acquired

messianic overtones because of their connotations with past rebellions,

were unfurled once more, this time as the Abbasids’ symbol. All those

signs and portents of a looming battle were widely circulated to create a

base for revolutionary hopes and millennial expectations (Shaban 1971,

183). The call to arms was accompanied by the vivid reenactment of

the martyrdom of Ali’s son, Husayn, at the hands of the Umayyad ruler,

Yazid, and the promise of justice and retribution once the Abbasids had

come to power. When, after months of secret and intense preparation,

the revolution fi nally broke out in Merv (present-day Turkmenistan) in

747, close to 10,000 people joined Abu Muslim’s command. In 750, Kufa

fell, and the fi rst spiritual leader of the Abbasid forces, Abu al-Abbas (r.

750-754), became the Commander of the Faithful (amir al-muminin).

Four years later, he was succeeded on the throne by his stronger and

more charismatic brother, Abu Jaafar al-Mansur (r. 754–775); by that

time, the last of the Umayyad family, Marwan II (r. 744–750), had been

defeated, and the new dynasty, refl ecting a wider mix of Arab and non-

Arab Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and even Buddhist populations, was

well on its way to bursting onto the world stage.

The Building of Baghdad

Abu Jaafar al-Mansur, the second caliph of the Abbasid Empire, decided

to build a new capital as a symbol of a new beginning. The building of

Baghdad is one of those highly symbolic moments in history that was

fortunately captured by Muslim historians either contemporary to or

living somewhat later than al-Mansur. One summer day in 762, it is

recounted, the caliph surveyed the spot on which his new capital was

to be erected and proclaimed it to be excellent. After praying the after-

noon prayer, he spent the night in a nearby church, “passing the sweet-

est and gentlest night on earth” (quoted in Hourani 1991, 33). The next

day al-Mansur was further impressed by the commercial opportunities

offered by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that tied Iraq to lands east

and west, as well as the immense potential for the provisioning and

resupply of his large land army. And so he is supposed to have ordered

the immediate building of his new capital on that very morning. After

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

78

calling for God’s mercy on himself and his subjects, he initiated the

project by laying the fi rst brick by hand.

Continuing with an ancient Iraqi tradition of constructing new cit-

ies outside the traditional population centers in the empire and in so

doing, underlying the shift from the old to the new, Baghdad was built

on a concentric plan in which the centers of power, such as the palace,

the military barracks, and the bureaucracy, were situated in the inner

core while the markets and residential quarters were located outside.

Refl ecting its structure, foreign observers referred to the new capital as

the “Round City.” However, for the Abbasid caliph who built it and for

all the Muslim chroniclers who recorded its development and transmit-

ted that lore over centuries, the city retained its original title, Madinat

al-Salam (the City of Peace). The name that ultimately stuck, Baghdad,

is the name of the village that previously existed on the site. In addition

to the palace-administrative complex, Baghdad spawned two large city

quarters, that of the Harbiyya (where the troops were situated), and

al-Karkh, the suburb where the builders and workmen lived and where

workshops, industries, and markets testifi ed to the bustling activity

generated by the ongoing building of the city.

After its inception, Baghdad went from strength to strength. From

the eighth to the 12th centuries, it was one of the most sophisticated

cities in the world, a multicultural hub of economic opportunity, intel-

lectual brilliance, and expanding social horizons. As al-Mansur had so

aptly prophesied, Baghdad became a thriving center of trade: it was not

only a major international transit point for goods but produced a num-

ber of valuable products of its own, such as textiles, leather, and paper.

Moreover, the city was thronged by people from all over the known

world—Christians, Jews, Persians, Arabs, Syrians, Africans, and people

from ma wara al-nahr (“what is beyond the river,” the Arab name for

Transoxania or Central Asia)—many of whom settled in Baghdad and

took up occupations that further added to the capital’s prospects. In the

words of a famous historian,

Baghdad, then, was the product of upheavals, population move-

ments, economic changes, and conversions of the previous cen-

tury: the home of a new Middle Eastern society, heterogeneous

and cosmopolitan, embracing numerous Arab and non-Arab

elements, now integrated in a single society under the auspices

of the Arab empire and the Islamic religion. Baghdad provided

the wealth and manpower to govern a vast empire: it crystal-

lized the culture which became Islamic civilization (Lapidus

1988, 70).

79

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

The Structures of Power in Abbasid Iraq

Under the Abbasids, a number of changes occurred in the political and

administrative structures of the empire. Among the most important

were those that underlined the transformation of the caliphate from an

Arab monarchy to an Islamic empire. While the Umayyads had relied

on the old Arab military and civilian elite, the Abbasids fl ung open

ELEVENTH-CENTURY

BAGHDAD, AS DESCRIBED

BY A HISTORIAN WHO

CALLED IT HOME

Y

aqut al-Hamawi was an Islamic geographer of Greek origin who

traveled all over the Islamic Middle East, temporarily calling

Baghdad home. Originally, he sold books; later on, he wrote them. In

his great work the Dictionary of Nations (Mu’jam al-Buldan), completed

in 1228, Yaqut wrote a historical geography of the Arab-Islamic world

that is still considered to be one of the best references written on the

towns, districts, and regions he visited. One of the accounts he related

concerned the almost magical properties attributed to Baghdad under

the Abbasids. The legend had it that because a reigning caliph had built

the city, no Abbasid ruler would ever die in it. Yaqut confi rms this by

writing a remarkable postscript to the story:

And one of the strangest [of the strange things that happened]

is that Al-Mansur died as a hajji [a religious pilgrim on his way

to Mecca]; his son Al-Mahdi went out to the mountain districts

and died . . . in Radh; Mahdi’s son Al-Hadi died in the village of

‘Isabad, east of Baghdad; while [yet another son] Al-Rasheed died

in Tus [Persia]; Al-Amin [Al-Rasheed’s son] was killed . . . on the

eastern front; Al-Mamun [Amin’s brother] died in Badhandoun

. . . in Syria; and Al-Mu’tasim, Al-Wathiq, Al-Mutawakil and

Al-Muntaser, and the rest of the Abbasid Caliphs died in Samarra

[a town north of Baghdad].

Source: Shihab Al-Din Abi Abdullah (Yaqut bin Abdullah al-Baghadi 1990,

546) Al-Rumi Al-Baghdadi. Mu’jam Al-Buldan (The dictionary of nations).

Edited by Farid Abdul-Aziz Al-Jundi. Vol. I. Beirut: Dar Al-Kutub Al-

Ilmiyya, 1990, p. 546.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

80

the doors of their empire to people from every ethnicity and sect. As

a result of the concerted effort to diversify the structures of state and

society in keeping with the pluralistic character of the new imperial

government, recruits from all over the empire were brought in to staff

the provincial administrations of the extended state. Even so, and as

with any state determined to succeed in a region prone to endemic

instability, there was a deliberate effort to create a new set of loyalties to

the Abbasid dynasty by creating fresh constituencies in key provinces.

Formerly marginalized groups such as the Khurasanis, made up of a

mix of Persian and Arab settlers, were now placed in highly sensitive

government positions. Nestorian Christians and Jews were also granted

opportunities in the new Islamic empire; as were the Shia, or partisans

of Ali, who had provided the Abbasids with their early ideological legit-

imization. The very multiplicity of the new governing group buttressed

the cosmopolitanism of Abbasid Islam and reinforced the empire’s wide

latitude for social distinctions and differences.

In Baghdad itself, government became more effi cient as an elaborate

bureaucracy grew around the caliph. The offi ces of the qadi (judge), the

controller of state fi nances, and the barid (courier) expanded as their

functions became more complex. An entirely new post—that of the

wazir, or chief minister—came into existence to execute the instruc-

tions of the caliph; eventually, this position, which may well have been

adapted from Sassanian example, was to become the most powerful in

the Abbasid state. Nurturing this newly installed administrative tradi-

tion was the use of Arabic as the lingua franca of the empire (replacing

Persian in former Sassanian territories), which created incentive to

write instruction booklets and other how-to manuals important for the

development of the bureaucratic class. The wide usage of Arabic also

allowed a new form of literature to emerge in the Abbasid realm that

drew from several cultural traditions within the larger empire. Finally,

military reorganization followed in the wake of this administrative

shake-up, as the caliph dismissed the Arab regiments that had been the

mainstay of the Umayyad caliphate and relied instead on the Khurasani

troops that had brought him and his family to power.

For an example of the changes in administration under the Abbasid

state, a look at Syria, the home region of the defeated Umayyad, is rele-

vant. On the provincial level, the shift from Damascus to Baghdad was

accompanied quite naturally by a diminution of the power of Syrian

Arab notables. In their place, however, the caliphs in Baghdad either

appointed younger Arab kinsmen, who, while capable governors,

did not enjoy the same legitimacy as the Abbasid ruling family and

81

ABBASID AND POST-ABBASID IRAQ

therefore could not inspire revolts against the center, or military men

from Khurasan, the heartland of the Abbasid revolt. Syria was divided

into fi ve administrative sections (ajnad), namely, Palestine (Filastin),

Jordan (al-Urdunn), Damascus (Dimashq), Homs, and Quinnesrin

(Cobb 2001, 11). Whereas under Umayyad rule Damascus had been

the hub of the universe, under the Abbasids, Jerusalem took on more

importance because of its association with the Muslim pilgrimage and

its holy sites.

Because the Muslims were locked in perpetual hostilities with the

Byzantine Empire to the west, the frontier in Syria became central to

Abbasid strategy: border districts demarcating Syria from the Byzantine

territories were heavily defended by Abbasid troops. Those fl uctuating

borders, called al-awasim or al-thughur by Muslim historians, were a

central theme of Islamic history and were given considerable attention

by the Muslim chroniclers of the medieval period. Finally, as in most

other Abbasid provinces, the governor of Syria was sometimes also the

chief tax collector, as well as the prayer leader on Fridays, the chief

judge, and overall military commander.

Syria, like Iraq, Egypt, and Iran, was directly governed. After the fi rst

fl ush of conquest had begun to make way for a more complex admin-

istration, a cadre of provincial offi cials, of which the governor was not

always the longest serving, gradually took the reins of power. As the

empire became more bureaucratic, posts became more specialized, and a

division of functions occurred so that provincial bureaus of taxation, the

judiciary, and the military commander began to make their appearance.

Try as it might, however, the Abbasid state was not able to control

all the provinces under its rule with equal effi ciency. Distant prov-

inces, such as those in Central Asia and in North Africa, fell back on

local family rule. For example, as early as the mid-ninth century, a

local dynasty, the Tahirids, began to govern the important province of

Khurasan. Meanwhile, regions of Central Asia came under the rule of

the Samanids in the same period. In North Africa, Tripolitania (now in

Libya) and regions that are now in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia threw

out their Arab commanders and formed new, sometimes short-lived

dynasties with the support of non-Arab, Berber tribes; signifi cantly,

some of these states adopted forms of the Khawarij or pro-Shia posi-

tions, which were by then completely inimical to Abbasid interests.

Faced with the reality of local warlords taking over the reins of power,

the Abbasids acquiesced in their rule, so long as the required taxes to the

empire were paid. While the warning signs of an overstretched empire

crumbling at the edges were all but ignored for the sake of realpolitik