Engerman S.L., Gallman R.E. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Vol. 1: The Colonial Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Economic

and Social Development of the South 277

year in the 1710s, almost 900 in the 1720s, and more than 2,000 in the

1730s. Slaves were a majority in colonial Carolina by 1708 and accounted

for 72 percent of the population by 1740, making the region seem "more

like a negro country than like a country settled by white people."

1

' The

change is also evident in the difficulties both whites and blacks had

achieving reproduction, as the export boom and the articulation of a

plantation complex brought the destructive demographic regime of the

sugar islands to the lowcountry. The impact on slaves was especially harsh,

because rise production (like sugar) consumed workers. "The cultivation of

it is dreadful," the author of

American Husbandry

noted, a "horrible employ-

ment, . . . not far short of digging in Potosi."

16

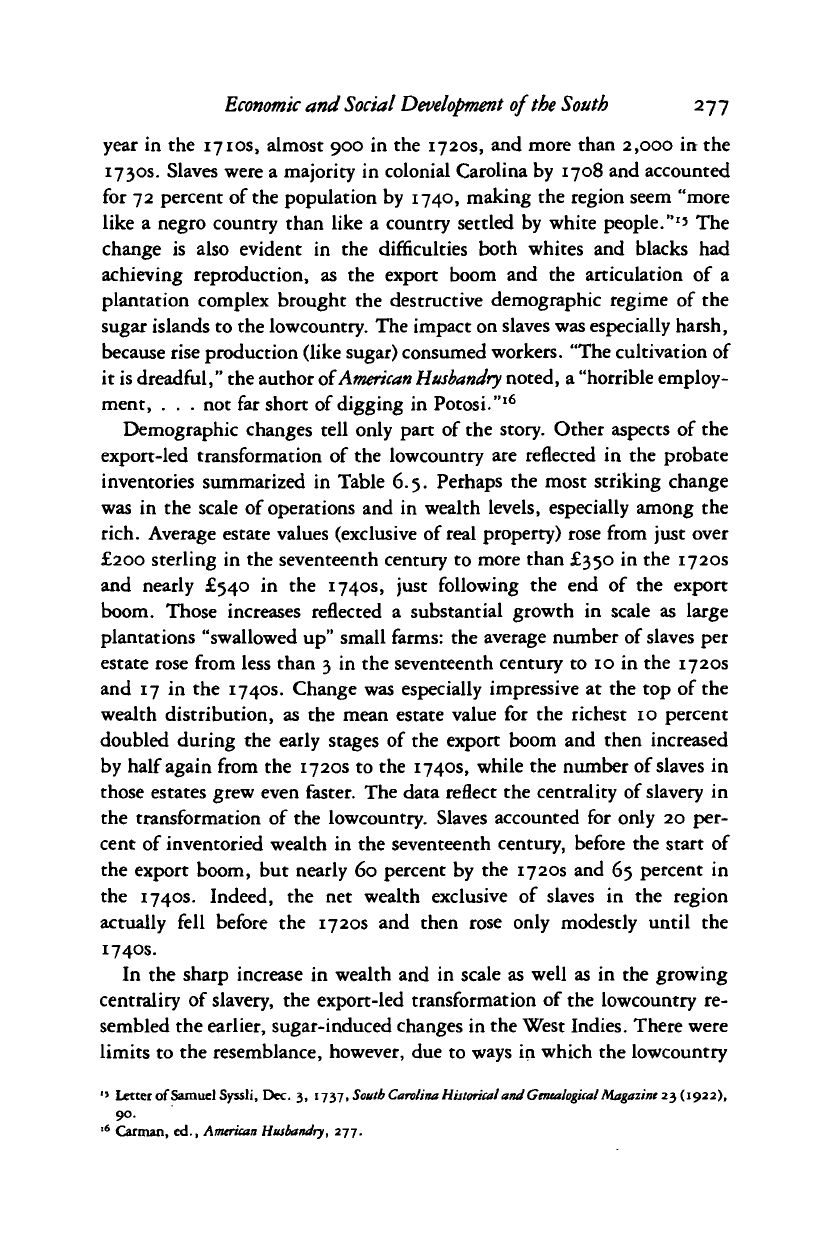

Demographic changes tell only part of the story. Other aspects of the

export-led transformation of the lowcountry are reflected in the probate

inventories summarized in Table 6.5. Perhaps the most striking change

was in the scale of operations and in wealth levels, especially among the

rich. Average estate values (exclusive of real property) rose from just over

£200 sterling in the seventeenth century to more than £350 in the 1720s

and nearly £540 in the 1740s, just following the end of the export

boom. Those increases reflected a substantial growth in scale as large

plantations "swallowed up" small farms: the average number of slaves per

estate rose from less than 3 in the seventeenth century to 10 in the 1720s

and 17 in the 1740s. Change was especially impressive at the top of the

wealth distribution, as the mean estate value for the richest 10 percent

doubled during the early stages of the export boom and then increased

by half again from the 1720s to the 1740s, while the number of slaves in

those estates grew even faster. The data reflect the centrality of slavery in

the transformation of the lowcountry. Slaves accounted for only 20 per-

cent of inventoried wealth in the seventeenth century, before the start of

the export boom, but nearly 60 percent by the 1720s and 65 percent in

the 1740s. Indeed, the net wealth exclusive of slaves in the region

actually fell before the 1720s and then rose only modestly until the

1740s.

In the sharp increase in wealth and in scale as well as in the growing

centrality of slavery, the export-led transformation of the lowcountry re-

sembled the earlier, sugar-induced changes in the West Indies. There were

limits to the resemblance, however, due to ways in which the lowcountry

11

Letter of Samuel Syssli, Dec. 3, 1737,

South

Carolina Historical andGenealogical Magazine 23 (1922),

90.

•

6

Carman, ed.,

American

Husbandry, 277.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

278 Russell R. Menard

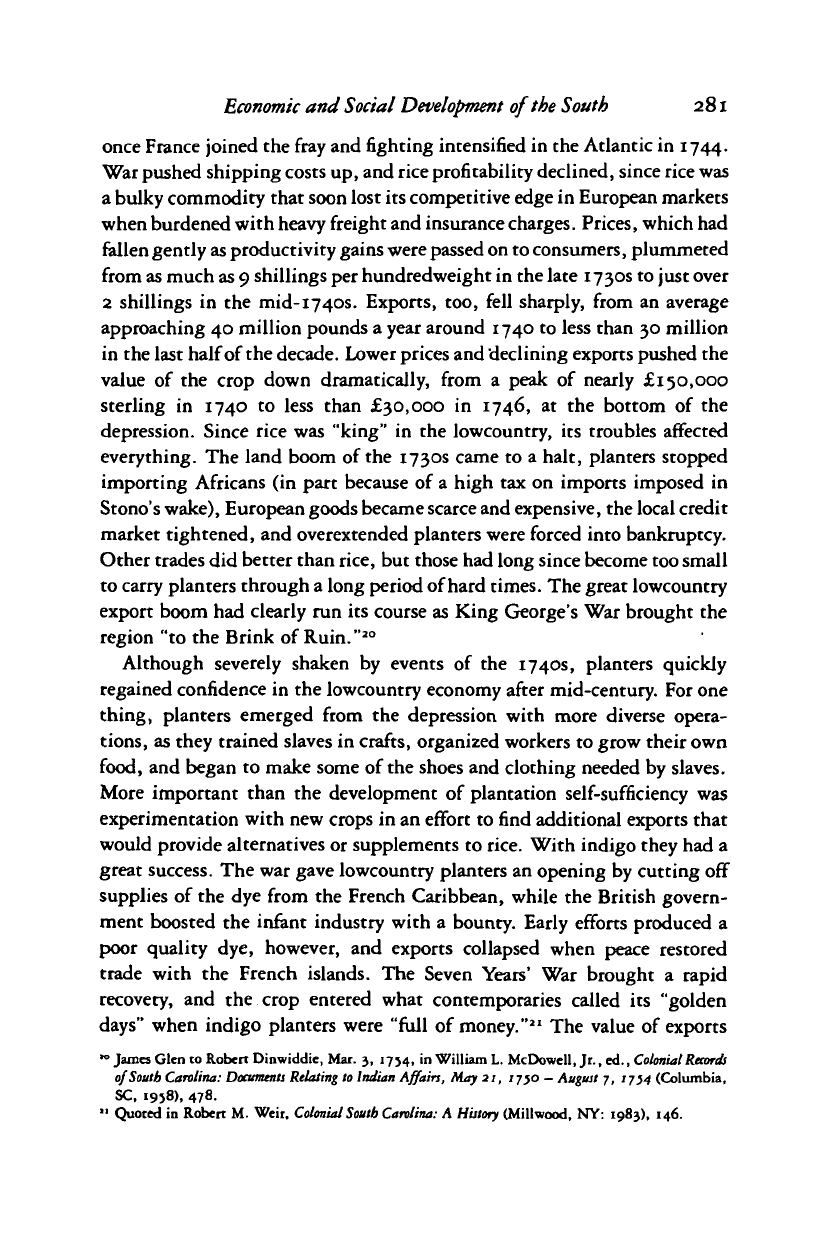

Table 6.5.

Some characteristics

of

lowcountry South

Carolina

probate

inventories,

1678-1764

N inventories

Mean movables (in sterling)

%

wealth in slaves

Slaves per estate

%

estates with slaves

%

planters with slaves

%

estates with land

%

planters with land

Share wealth, top 10%

Share slaves, top 10%

Mean wealth, top 10%

Mean slaves, top 10%

Mean nonhuman movable wealth

1678-98

50

204

21

2.6

62

69

—

—

41

48

£835

12.6

£161

1722-6

158

357

58

9.6

78

93

73

90

46

49

1,636

46.8

150

1743-5

154

539

65

16.7

81

94

70

93

44

43

2,422

74.5

189

1764

142

1,145

54

17.9

88

96

68

92

60

51

7,018

92

527

Sources: Records of the Secretary of the Province, 1675-95, 1692-1700, 1700-10,

1722-6; Wills, Inventories

&

Miscellaneous Records, 1722-4, 1724-5; Inventories,

1739-^4,

1744-6, 1763-7. South Carolina Department of Archives and History,

Columbia. All values converted to sterling following the exchange rates in John J.

McCusker,

Money

and

Exchange

in

Europe and

America,

1600-1775: A

Handbook

(Chapel Hill, NC: 1978), 222^1. For the period before 1699, when McCusker

reports no exchange rates, I assumed that £1 sterling equaled £1.1 in South Carolina

currency. Readers should note that these figures have not been adjusted for changes

in age structure among inventoried decedents or for changes in the proportion of

wealthowning decedents whose estates were inventoried.

developed

its own distinctive plantation complex. Some of

the

differences

are

apparent in the probate

inventories.

Remarkably, the export boom was

accompanied

by little increase in inequality among

wealthowners

and by

widespread

access to the basic factors of

production

among whites. In the

1740s,

following half a century of rapid growth, the share of wealth

owned

by the richest

10

percent barely differed from seventeenth-century

levels,

while the great majority of decedents (and nearly all planters)

owned

both land and

slaves.

The export boom had made the lowcountry a

republic

of

slaveowners.

Other

developments further distinguished the lowcountry from the

sugar

islands. For one thing, in Charlestown, British America's fourth

largest

city for most of the eighteenth century, the lowcountry had a

commercial,

political, and social center that provided a focus not found in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and

Social Development

of the

South

279

the West Indies. For another, the region developed a merchant class much

larger and wealthier and with more independence than in the sugar is-

lands,

where traders remained thoroughly subordinate to metropolitan

interests. Thirdly, a region of "common husbandry" developed around the

edges of the plantation district, providing planters food for their slaves

and Charlestown merchants a

flow

of diversified products for export and a

lively market for manufactured goods and commercial services. Perhaps

most important were differences in scale. Rice plantations were large by

mainland standards but much smaller than sugar

estates;

lowcountry plant-

ers were not as rich as sugar magnates. As a result, absenteeism was more

limited in the lowcountry than on the islands, planters more often man-

aged their plantations, and they spent a larger share of their income at

home. The limits on planter absenteeism had important political conse-

quences, for it permitted the growth of an indigenous ruling class, a

powerful, self-conscious group capable of shaping the region's future.

The lowcountry's transformation was bought at a frightful price, par-

ticularly in the lives of Indian and African slaves, chief victims of the

planter's vicious scramble to capture the fruits of the export boom. It was

also expensive: over the course of the boom, planters spent roughly a

million sterling on slaves alone, to which must be added expenditures on

land, buildings, tools, and livestock needed to start plantations. Given

the costs, it is worth asking how the export boom was

financed.

There are

several possibilities. Planters could have borrowed from English investors

or on a local credit market, acquired short-term commercial credit from

English merchants, brought substantial capital with them when they

immigrated, or paid for slaves out of current income. All of these methods

were used in all of the colonies, but their importance differed between

regions. Outside capital was apparently a greater source of credit during

the Barbadian sugar boom than at other times or places. In the Chesa-

peake, the slow pace of Africanization suggests that savings and current

income played the central role. In coastal Carolina, a local mortgage

market that was developed early in the eighteenth century was especially

important. Planters were able to borrow funds to pay for agricultural

development, particularly for the purchase of Africans, in the local capital

market where Charlestown merchants loaned money earned in trade on

mortgages secured by land and, especially, slaves. The local mortgage

market played a key role in the growth of the Carolina economy. It

quickened the pace of development beyond what would have been possible

had planters been forced to rely on savings, while providing local lenders

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

280

Russell

R. Menard

the opportunity to make secure investments in a rapidly expanding export

sector. And it permitted small and middling planters with modest in-

comes but high aspirations, who perhaps seemed poor risks in other credit

markets, access to capital to acquire labor and build estates. If there was

any truth to the claims of Revolutionary ideologues that the lowcountry

was both a slaveholder's republic and a good poor man's country, the local

mortgage market deserves some credit for making their perverse vision a

reality.

The great lowcountry export boom ground to a halt around 1740 in a

series of events sufficiently disruptive and threatening to shake planter

confidence and make them wonder about the choices they had made and

the society they had built. The first shock was a yellow fever epidemic that

struck Charlestown in late August 1739, bringing with it a "great Sick-

ness & Mortality the like whereof has never been known in the Prov-

ince."

17

Coming on the heels of a major outbreak of smallpox the previous

year, the epidemic was terrifying. And it was only the beginning. On

September 9, with the fever still raging in the city, a small band of slaves

from the western branch of Stono River, hoping to reach the Spanish

settlement at St. Augustine, rose in insurrection. Although most of the

rebels were quickly "taken or Cut to Peices[«r]," the group grew to some

60 to 100 blacks on the march south, and they "murthered in their way

there between Twenty & Thirty white People & Burnt Severall houses."

18

Stono was the culmination of a decade of mounting African protest, a

resistance more frightening because of the supposed refuge at St. Augus-

tine and persistent rumors of an imminent Spanish invasion of the

lowcountry. And Stono was followed by continued unrest among slaves,

by a failed English invasion of

St.

Augustine, by a major fire in Charles-

town in September 1740 (attributed by some to black arsonists, feared by

others as likely opportunity for another insurrection), by the landing of

a

large Spanish force at St. Simon's off the Georgia coast, and by a gradual

slide into a long depression as the lowcountry economy felt the impact of

King George's War. "This province," Robert Pringle lamented, "Seems to

be Subject to Series of Accidents

&

Missfortunes."'

9

The 1740s depression marked a turning point in the history of the

lowcountry. King George's War (1739-48) hit the region hard, especially

•' Robert Pringle to Thomas Burrill, Oct. 10, 1739, Walter B. Edgar, ed., Tht

Lttterbook

of Robert

Pringle, 2 vols. (Columbia, SC, 1972), I, 139.

'' Pringle to John Richards, Sept. 26, 1739, ibid., I, 135.

'» Pringle to Andrew Pringle, July 10, 1742, ibid., I, 388.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and Social Development of the South 281

once France joined the fray and fighting intensified in the Atlantic in 1744.

War pushed shipping costs up, and rice profitability declined, since rice was

a bulky commodity that soon lost its competitive edge in European markets

when burdened with heavy freight and insurance charges. Prices, which had

fallen gently as productivity gains were passed on to consumers, plummeted

from as much as 9 shillings per hundredweight in the late 1730s to just over

2 shillings in the mid-i74os. Exports, too, fell sharply, from an average

approaching 40 million pounds a year around 1740 to less than 30 million

in the last half of the decade. Lower prices and declining exports pushed the

value of the crop down dramatically, from a peak of nearly £150,000

sterling in 1740 to less than £30,000 in 1746, at the bottom of the

depression. Since rice was "king" in the lowcountry, its troubles affected

everything. The land boom of the 1730s came to a halt, planters stopped

importing Africans (in part because of a high tax on imports imposed in

Stono's wake), European goods became scarce and expensive, the local credit

market tightened, and overextended planters were forced into bankruptcy.

Other trades did better than rice, but those had long since become too small

to carry planters through a long period of hard times. The great lowcountry

export boom had clearly run its course as King George's War brought the

region "to the Brink of Ruin."

20

Although severely shaken by events of the 1740s, planters quickly

regained confidence in the lowcountry economy after mid-century. For one

thing, planters emerged from the depression with more diverse opera-

tions,

as they trained slaves in crafts, organized workers to grow their own

food, and began to make some of the shoes and clothing needed by slaves.

More important than the development of plantation self-sufficiency was

experimentation with new crops in an effort to find additional exports that

would provide alternatives or supplements to rice. With indigo they had a

great success. The war gave lowcountry planters an opening by cutting off

supplies of the dye from the French Caribbean, while the British govern-

ment boosted the infant industry with a bounty. Early efforts produced a

poor quality dye, however, and exports collapsed when peace restored

trade with the French islands. The Seven Years' War brought a rapid

recovery, and the crop entered what contemporaries called its "golden

days"

when indigo planters were "full of money."

21

The value of exports

*° James Glen to Robert Dinwiddie, Mar. 3, 1754, in William L. McDowell, Jr., ed.,

Colonial Records

of South Carolina:

Documtnts

Relating to Indian Affairs, May 21, 1750 - August 7, 1734 (Columbia,

SC,

1958), 478.

11

Quoted in Robert M. Weir, Colonial

South

Carolina: A History (Millwood, NY: 1983), 146.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

282 Russell R. Menard

grew enormously, from an annual average of less than £10,000 in the early

1750s to nearly £150,000 in the early 1770s, when it approached 40

percent of the value of the lowcountry rice crop. The rise of indigo let

planters and merchants face the possibility of war with optimism, with the

hope that "a new War will learn us how to propogate

[sic]

other useful

Articles."

22

It was also critical to growing planter confidence that the slave popula-

tion seemed less threatening after mid-century. That is not to say that all

planters slept easily all the time, but Stono was the last major scare of the

eighteenth century. The reasons for growing planter confidence in their

abilities to control slaves are complex. Stono left masters determined to

discipline slaves more effectively; the Spanish threat gradually receded and

was finally eliminated when Florida passed to the British in 1763; and the

settlement of the backcountry left lowcountry whites, although still out-

numbered, confident of help should an emergency arise. Also important

were changes in the composition of

the

population and the organization of

plantation work. Many slaves, Gov. James Glen explained in 1751, "are

natives of Carolina" who "have been brought up among white people."

The conclusion Glen drew from this observation

—

that they had "no

notion of

liberty,

nor no longing after any other country," that slaves were

"pleased with their masters, contented with their condition, reconciled to

servitude"

—

is stunning in its complacency, but he did isolate an impor-

tant truth.

2

' The growth of a Creole majority, a process quickened when

African imports stopped in the 1740s, transformed the slave population in

ways that made them less terrifying to their owners. That transformation

also permitted slaves to form families, make firm and lasting friendships,

and build communities on the large lowcountry plantations. The slaves

also utilized the development of a task system to gain some control over

their working lives; this provided opportunities to work on their own

account and accumulate small amounts of property. Lowcountry slavery

remained harsh and oppressive, but the changes that occurred around mid-

century left blacks less willing to risk all in open rebellion.

The renewed success of

the

lowcountry rice industry provided a further

source of growing planter confidence. The value of the crop grew more

than threefold in the quarter-century following King George's War, from

roughly £115,000 sterling around 1750 to £380,000 in the early 1770s.

" Henry Laurens to Sarah Nickelson, Aug. I, 1755, Laurtns

Papers

I, 309.

*' Glen to the Lords Commissioners for Trade and Plantations, March 1751, in H. Roy Merrens, ed.,

The Colonial

South

Carolina

Scene:

Contemporary

Views, 1697-1774 (Columbia, SC: 1977), 183.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and Social

Development

of the South 283

It was not simply that the rice industry grew; planters achieved major

improvements in productivity, evident both in technical changes in rice

production and in the ability to hold prices stable in the face of rising

costs.

"The culture of

rice"

in the region, David Ramsay noted, "was in a

state of constant improvement" as production shifted first from the moist

uplands to inland swamps and later to the tidewater, as complex irrigation

systems were developed, as new varieties were discovered better suited to

local conditions, and as the cleaning process was improved.

2

'* It is possible

that this creativity rested on the skills of slaves. Indeed, it has been

suggested that Africans introduced the technology of rice cultivation to

the lowcountry and that rice planters sought (and paid premium prices for)

slaves from ethnic groups familiar with the crop. While the notion that

technological restraints were removed only with the arrival of skilled

Africans after having been a major barrier to the commercial cultivation of

rice seems insufficiently attentive to the key role played by rising Euro-

pean demand, Africans did bring important technical skills across the

Atlantic, and the abilities and accumulated knowledge of

slaves

was cru-

cial to the success of plantation economies. This may have been particu-

larly true with rice. The crop was widely grown in West Africa under a

variety of conditions and by different techniques, while the lowcountry

.

tasking system placed major responsibilities for the organization of work

in the hands of slaves and offered them incentives to work efficiently. It

would not be surprising if some of the productivity gains rested on innova-

tions by slaves. Planters took the credit, however, reading into the re-

newed expansion of the rice industry, the growing diversity of their planta-

tions,

the rise of

indigo,

and the general success of lowcountry agriculture

clear evidence of their creativity and inventiveness, their ability to manage

slaves and deal with adversity, and their competence to shape the future.

The growing expansiveness of lowcountry planters was reflected in the

geographic expansion of the lowcountry plantation complex. Georgia was

the focus of that expansion and its greatest

success.

Georgia's founders had

not intended that the colony become a "new Carolina." The Georgia

Trustees designed the colony as an area of "common husbandry," a settle-

ment of farms rather than plantations where a society of sturdy white

yeomen would work for their own account without slaves, forming both a

buffer against Spanish and French ambitions and a refuge for England's

dispossessed. By the early 1750s, only 20 years after the colony's found-

*• David Ramsey,

The

History of

South

Carolina,

from

Its First Sett/meat in /670, to the

Year

1808, 2 vols.

(Charleston, SC, 1809), II, 206.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

284 Russell R. Menard

ing, the vision had collapsed, victim of the Trustee's incompetence, the

ambitions of Georgia settlers, and the demands of Carolina planters for

fresh rice lands. The prohibition against slavery was lifted, planters and

slaves poured in, and Georgia became both a royal colony and "a province

to South Carolina" as the lowcountry plantation complex took root on the

coastal strip and along the southern bank of the Savannah River, f" By

1770,

blacks were 45 percent of the colony's population (70 percent in the

coastal strip), its rice and indigo crops worth more than £40,000 sterling.

The years before the Revolution also witnessed the spread of the

lowcountry plantation complex to the lower Cape Fear region of North

Carolina

as

well

as

efforts

to

establish it below

the

Altamaha River and in the

newly acquired colony of East Florida. The Cape Fear district had become a

South Carolina satellite much earlier, in the 1730s, as the naval stores

industry displaced by the expansion of rice moved north. By the 1760s, the

process that had earlier transformed coastal South Carolina reached the

lower Cape Fear when large plantations, rice, indigo, and slaves pushed

small farmers and naval stores producers into the interior. The other efforts

proved less successful. The Altamaha project collapsed almost before it

started, as royal authorities first prohibited settlement while the region was

claimed by Spain and then, after 1763 when the Spanish claim was re-

moved, proved unable to settle complex land title disputes that had to be

unraveled before investment could proceed. East Florida at least got off the

ground when British investors went "Florida mad" and lowcountry planters

moved in to build a new Carolina. A few large plantations were established

and small crops of indigo produced by the early 1770s, but that effort too

proved a failure as investors fell victim to the strange environment and

(again) British administrative incompetence.

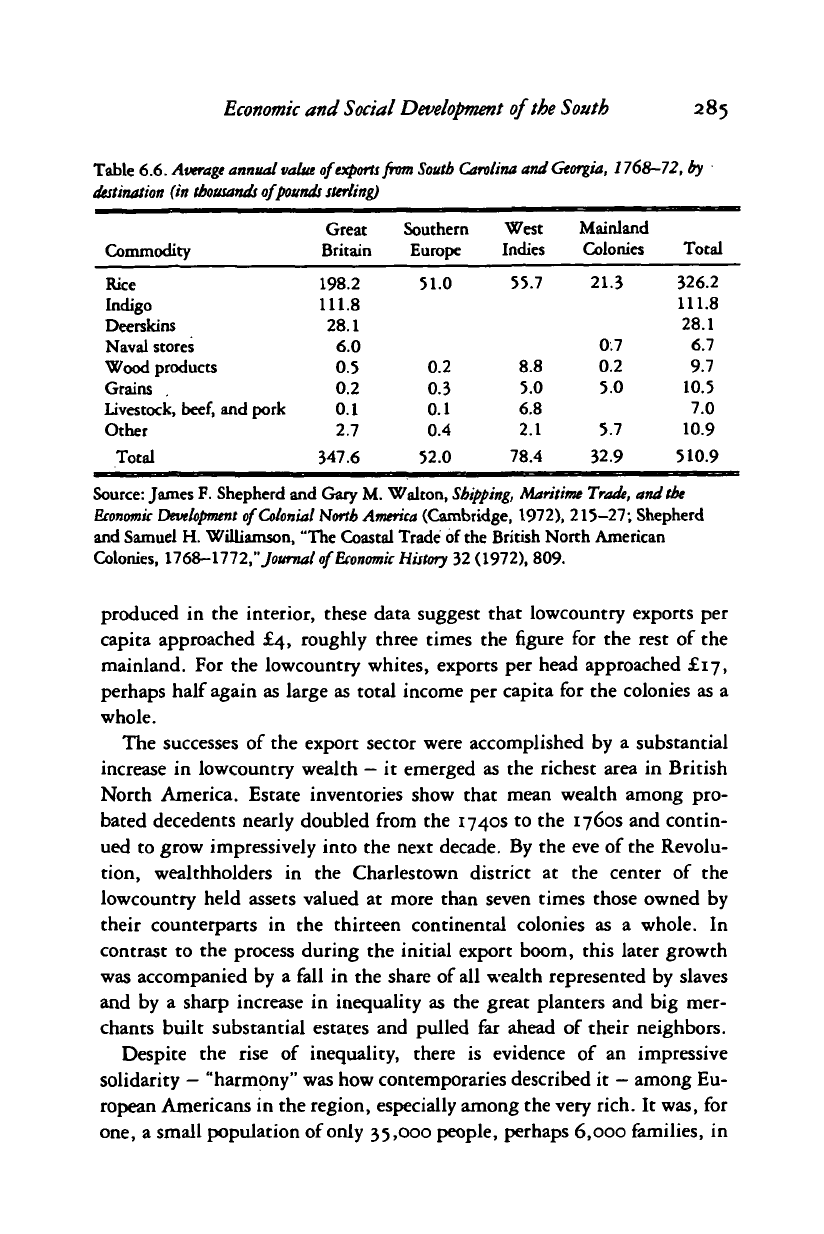

The success of rice and indigo and the geographic expansion of the

plantation complex suggest that the lowcountry export sector witnessed

extraordinary growth in the quarter-century before the American Revolu-

tion. Comprehensive trade statistics specific to the region are not avail-

able,

but data for South Carolina and Georgia capture the pattern. In

1748,

when Georgia's exports were minimal, a contemporary valued ex-

ports from South Carolina at £160,000 sterling. Between 1768 and 1772,

exports from South Carolina and Georgia were worth an average of

£511,000, a more than threefold increase in only 20 years (Table 6.6). If

we exclude all commodities but rice and indigo as likely to have been

*> James Habersham to Benjamin Marty n, March 15, 1756, Habersham Papers, Library of Congress.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and Social Development of the South 285

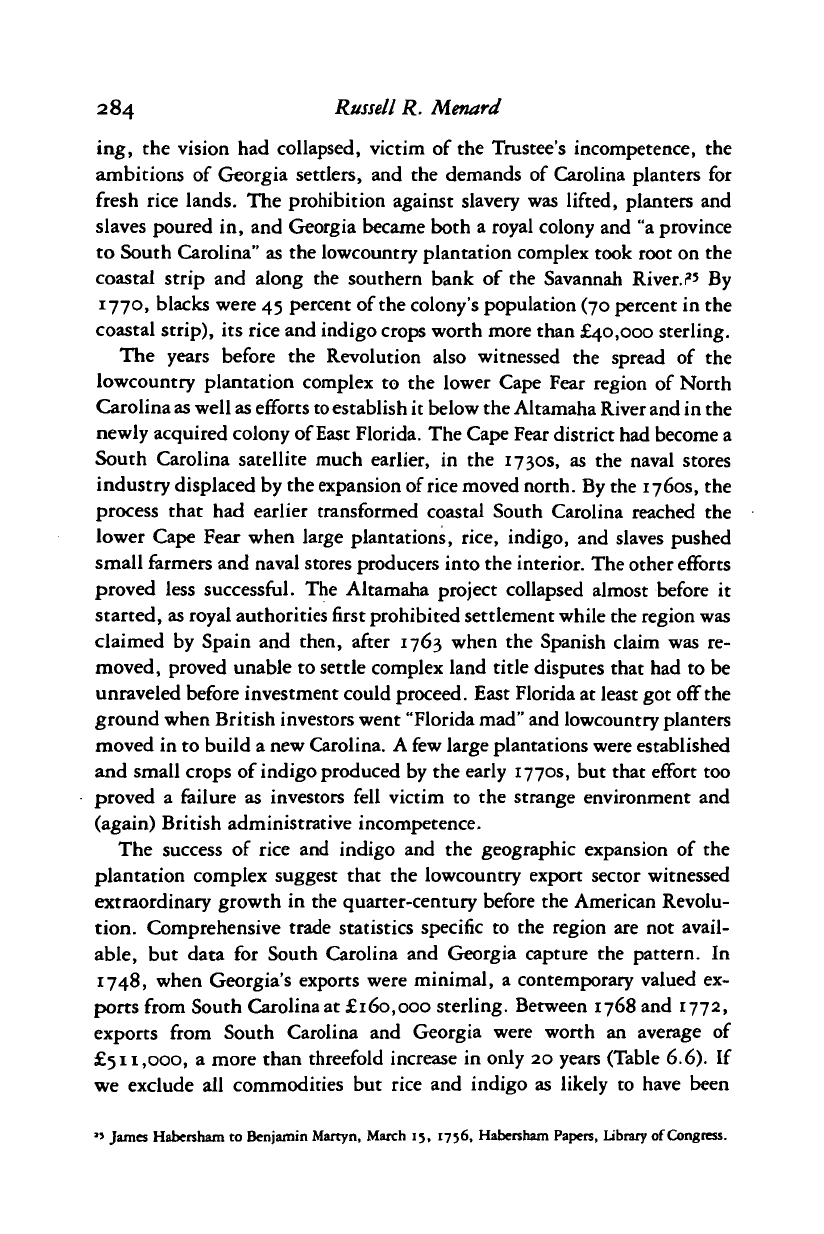

Table 6.6.

Average

annual

value

of exports

firm

South Carolina

and

Georgia,

1768-72, by

destination (in thousands

of

pounds sterling)

Commodity

Rice

Indigo

Deerskins

Naval stores

Wood products

Grains

Livestock,

beef,

and pork

Other

Total

Great

Britain

198.2

111.8

28.1

6.0

0.5

0.2

0.1

2.7

347.6

Southern

Europe

51.0

0.2

0.3

0.1

0.4

52.0

West

Indies

55.7

8.8

5.0

6.8

2.1

78.4

Mainland

Colonies

21.3

0.7

0.2

5.0

5.7

32.9

Total

326.2

111.8

28.1

6.7

9.7

10.5

7.0

10.9

510.9

Source:

James F. Shepherd and Gary M. Walton,

Shipping,

Maritime

Trade,

and the

Economic Development

of Colonial

North America

(Cambridge, 1972), 215-27; Shepherd

and Samuel H. Williamson, "The Coastal Trade of the British North American

Colonies, 1768-1772,"

Journal

of

Economic History

32 (1972), 809.

produced in the interior, these data suggest that lowcountry exports per

capita approached £4, roughly three times the figure for the rest of the

mainland. For the lowcountry whites, exports per head approached £17,

perhaps half again as large as total income per capita for the colonies as a

whole.

The successes of the export sector were accomplished by a substantial

increase in lowcountry wealth

—

it emerged as the richest area in British

North America. Estate inventories show that mean wealth among pro-

bated decedents nearly doubled from the 1740s to the 1760s and contin-

ued to grow impressively into the next decade. By the eve of the Revolu-

tion, wealthholders in the Charlestown district at the center of the

lowcountry held assets valued at more than seven times those owned by

their counterparts in the thirteen continental colonies as a whole. In

contrast to the process during the initial export boom, this later growth

was accompanied by a fall in the share of all wealth represented by slaves

and by a sharp increase in inequality as the great planters and big mer-

chants built substantial estates and pulled far ahead of their neighbors.

Despite the rise of inequality, there is evidence of an impressive

solidarity - "harmony" was how contemporaries described it - among Eu-

ropean Americans in the region, especially among the very rich. It was, for

one,

a small population of only 35,000 people, perhaps 6,000 families, in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

286

Russell

R. Menard

1775,

a group bound together

by

frequent face-to-face contact, high

rates

of

intermarriage, and a gradual blurring of

the

distinction between merchant

and planter. It was also a population bound together by its isolation: the

substantial black majority within the region and the restive backcountry

farmers encircling it to the west combined to curb disagreements and foster

group consciousness. In the end, however, that solidarity

was

rooted less in

fear and isolation than in

an

optimism and expansiveness that grew out of a

defining characteristic of the lowcountry plantation regime: an impressive

prosperity that provided most white men access to land and labor, made a

favored few very rich indeed, and took the region into the revolutionary era

as a slaveowner's republic.

BACKCOUNTRY AND FRONTIER

In contrast to the coastal districts, where the regional constructs of

lowcountry and tobacco coast have a certain integrity and firmness,

backcountry and frontier are problematic concepts. Despite the still-

looming presence of Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis, this re-

flects the force of historiographic tradition. At least among colonialists,

the interior has received much less attention than the seaboard. It also

reflects reality. True, there is some fuzziness about the edges of

the

coastal

regions, especially the Chesapeake, where high rates of migration led to

rapid expansion and the sometimes problematic integration of new terri-

tory, and where diversification had removed some older settlements from

the tobacco economy by the revolutionary era. However, lowcountry and

tobacco coast were held together by a shared commitment to common

exports, plantation agriculture, and African slavery as well as by emerging

planter classes gradually consolidating power, growing in solidarity, and

developing a vision for the future. Backcountry and frontier lacked the

stability and cohesiveness produced by such integrating institutions. They

were places in the process of transformation as the aspirations of settlers

joined with the aggressive expansion of tidewater society to first turn

frontier into backcountry and then build a plantation regime in the

backcountry settlements.

The characteristic economic institution of the southern frontier was the

trade in animal pelts, especially deerskins, much in demand in Europe

where they were turned into gloves and bookbindings. Unfortunately, it is

impossible to describe the volume of that trade precisely. Deerskins were

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008