Engerman S.L., Gallman R.E. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Vol. 1: The Colonial Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

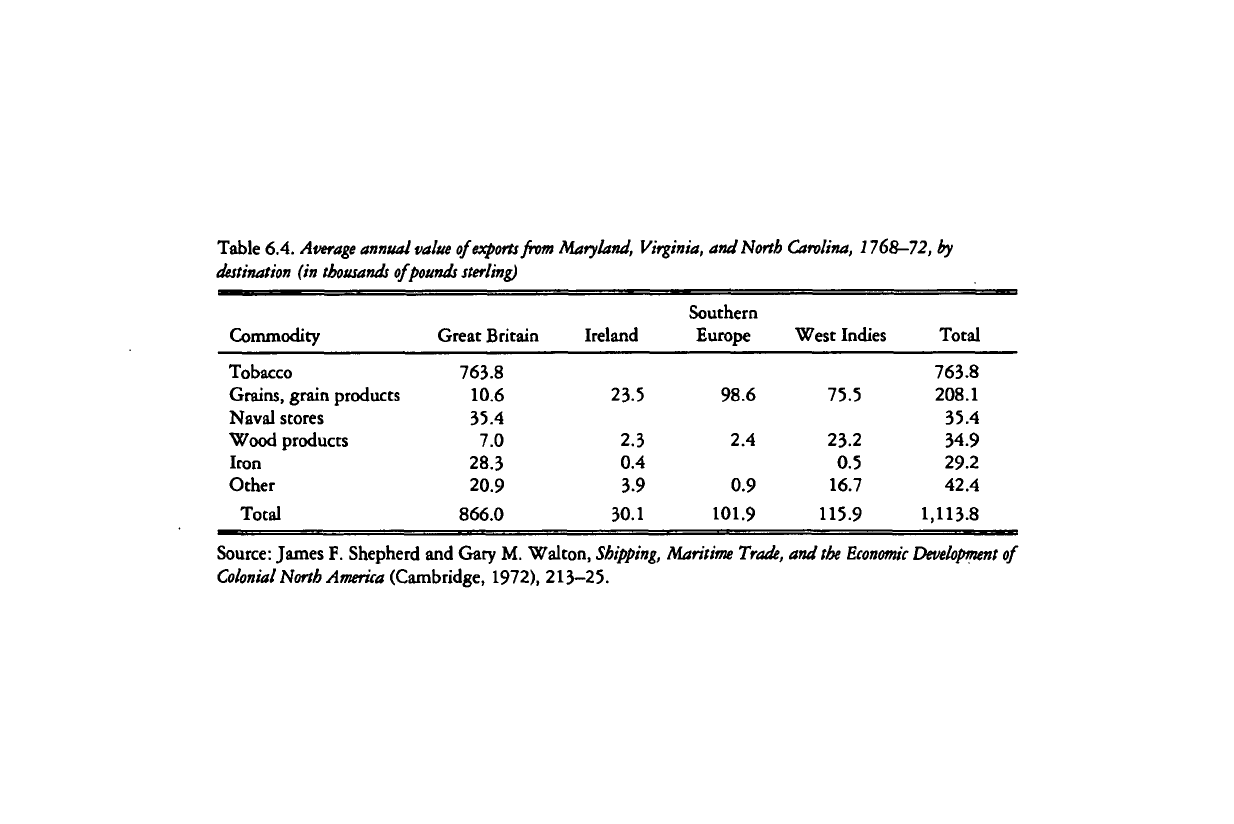

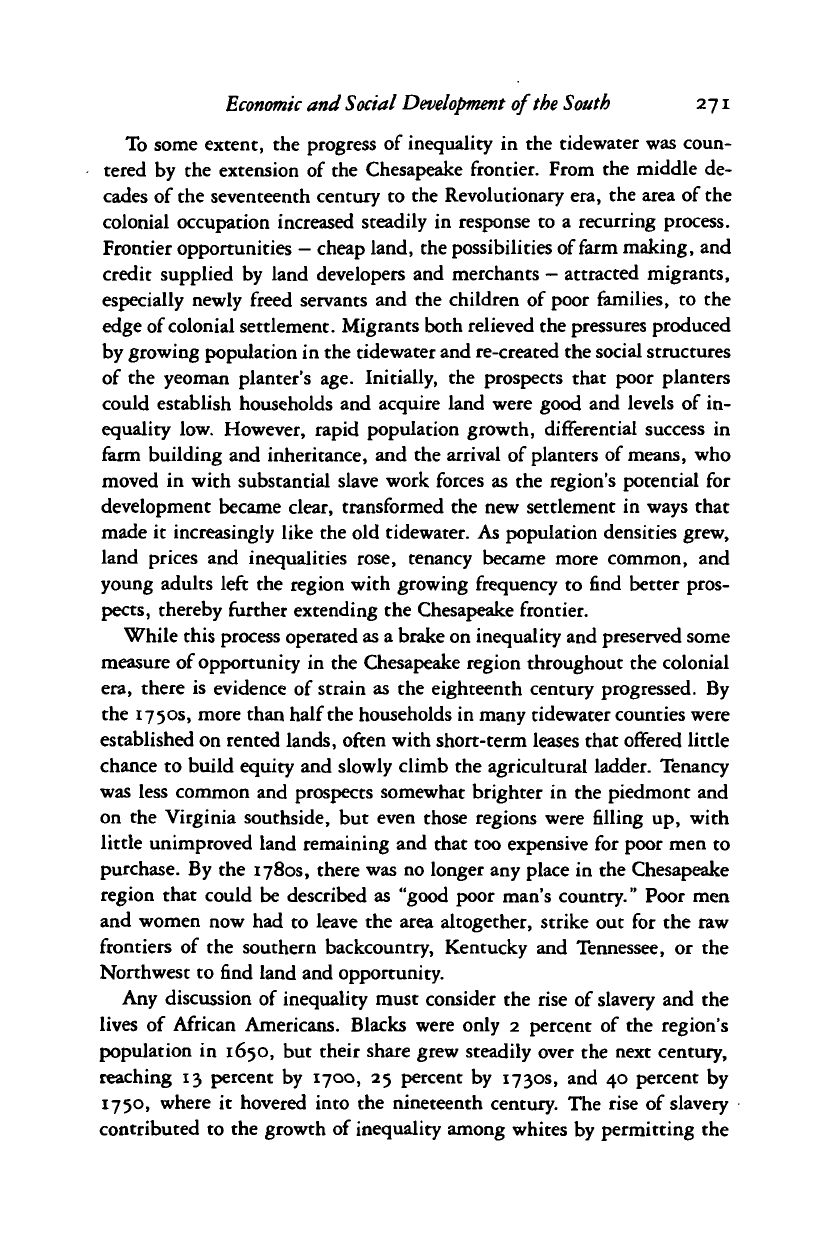

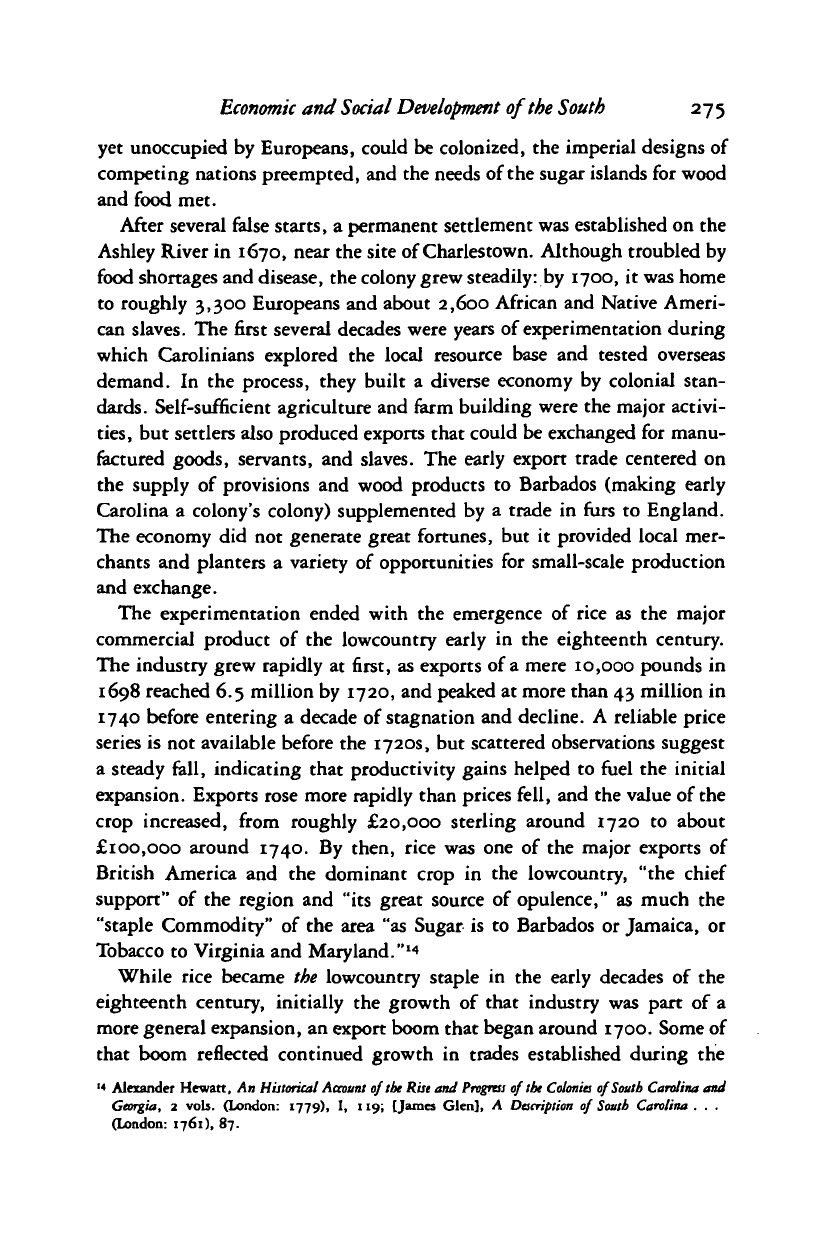

Table 6.4.

Average

annual

value

of exports from

Maryland,

Virginia, and

North

Carolina,

1768-72,

by

destination

(in

thousands

of

pounds sterling)

Commodity

Tobacco

Grains, grain products

Naval stores

Wood products

Iron

Other

Total

Great Britain

763.8

10.6

35.4

7.0

28.3

20.9

866.0

Ireland

23.5

2.3

0.4

3.9

30.1

Southern

Europe

98.6

2.4

0.9

101.9

West Indies

75.5

23.2

0.5

16.7

115.9

Total

763.8

208.1

35.4

34.9

29.2

42.4

1,113.8

Source: James F. Shepherd

and

Gary M. Walton,

Shipping,

Maritime Trade, and

the Economic Development of

Colonial

North

America

(Cambridge,

1972),

213-25.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

268

Russell

R. Menard

depressions in the industry during the late 1720s to early 1730s and again

in the mid-i74os. Prices rose fairly steadily after 1750, although there

were periods of contraction in the later stages of the Seven Years' War and

in the aftermath of the British credit crisis of 1772. Rising prices joined

with growing output to push up incomes, bringing an era of unprece-

dented prosperity to the tobacco coast while extending cultivation of the

crop and tidewater social institutions into Virginia's southside and

piedmont regions.

The eighteenth-century expansion of the export sector led to some

modest urbanization in the area. The region had been almost entirely rural

before 1720. The extensive river system permitted decentralized trade,

while tobacco needed little processing and did not require elaborate stor-

age facilities or a highly developed internal transport network. Further,

the trade was controlled by metropolitan rather than colonial merchants,

which meant that transport and finance remained in English hands.

Changes in the organization of the tobacco trade led to a proliferation of

small towns in the plantation district after 1720 as the colonial legisla-

tures set up inspection and warehouse systems to control quality, and

British merchants centralized collection of the crop to reduce port times

for the fleet. The most important developments occurred on the periphery

of the plantation sector and reflected the diversification of

exports.

Grains

required more processing, storage, and transport facilities than tobacco,

and the grain trade was dominated by local rather than metropolitan

merchants. Baltimore and Norfolk, each with about 6,000 inhabitants in

1775,

were the two largest cities in the region by far. Each owed its

success more to the relatively modest business of supplying grains and

wood products to the Caribbean and southern Europe than to the much

larger tobacco trade with Great Britain.

The expansion of the export sector first stretched and then transformed

the Chesapeake system of husbandry. To take advantage of eighteenth-

century opportunities in grains, planters had to find ways around the land

and labor constraints that made it impossible to raise large surpluses of

corn or wheat without cutting back on tobacco. Some labor time was freed

up by the introduction of

plows,

a possibility once the region was defor-

ested and fields slowly cleared of stumps and roots. The change in the

work force also provided additional time since planters could push slaves

harder than indentured servants, making them work more intensely for

more hours in the day and more days in the year. Some of the new labor

time was used to pen and feed livestock, which meant that manure was

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and

Social Development

of the

South

269

made available to fertilize fields, permitting shorter fellow periods and

higher yields per acre. These changes were related in what has been called

"the plow—corn—livestock—manure complex."

11

The use of plows during

planting season released labor that could be used to grow more corn; the

corn was fed to animals, now penned, fed, and trained to the plow; and

the animals produced fertilizer, which permitted planters to add workers

without adding new land. While the new complex eventually exhausted

and eroded the soil, it allowed planters to respond to the rising prices for

food and tobacco and made an important contribution to Chesapeake

prosperity.

A remarkable set of probate records permit estimates of wealth per

capita on Maryland's lower western shore from the mid-seventeenth cen-

tury to the Revolution. These show a rapid increase at a rate of about 2.5

percent annually from 1660 to the early 1680s followed by a slight decline

to the beginning of the eighteenth century. Per capita wealth then leveled

out or perhaps fell gently until about 1750 before growing rapidly, again

at a yearly rate of roughly 2.5 percent, in the quarter-century preceding

independence. The pattern seems consistent with an export-led growth

process. The seventeenth-century expansion of the tobacco industry appar-

ently led to real gains in income and wealth, while the period of stagna-

tion around 1700 produced decline. The renewed expansion of tobacco

exports after 1720 ended or at least slowed the decline, but this growth

was achieved without major productivity gains and through the geo-

graphic extension of cultivation. It was not of the sort to produce rising

wealth per head. Beginning in 1750, however, rising prices for grains and

tobacco created new opportunities and drove per capita wealth to new

highs.

Apparently, incomes along the tobacco coast were driven by the

foreign sector.

Or

so

it would seem. However, there are difficulties with the argument,

at least for the seventeenth century. For one thing, income per head from

tobacco declined sharply until 1640 and then fell slowly. The staple placed

a floor under incomes, but it was an unstable floor with a gently falling

slope. For another, when wealth levels for the lower western shore are

disaggregated, it becomes clear that each neighborhood went through a

period of initially rapid increase lasting about 20 years followed by a

leveling out, with the timing of change related not to the behavior of

11

The phrase is from Lois Green Cart and Russell R. Menard, "Land, Labor, and Economies of Scale

in Early Maryland: Some Limits to Growth in Chesapeake System of Husbandry," Journal of Economic

History 49 (1989), 417.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

270

Russell

R. Menard

tobacco exports but to the date of settlement and to rising dependency

ratios as the population shed its early, frontier characteristics.

The increase in wealth during the seventeenth century occurred despite

falling income per head from exports and in the face of demographic

changes that reduced the share of the population in the work force. The

gains were a result of farm building. New settlements were poor and

living standards crude, but carving out farms provided opportunities for

saving, investment, and accumulation and pushed wealth levels up. Fami-

lies worked hard to clear land, erect buildings and fences, build up their

livestock herds, plant orchards and gardens, construct and improve their

homes. While these activities drove per capita wealth higher, there were

limits to the process. Once it had a farm in full operation, there was little

a family could do to further increase wealth. The early growth spurt was

followed by a long period of

stability,

perhaps by slight decline as depen-

dency ratios continued to rise, lasting until the mid-eighteenth century.

World food shortages, rising prices for tobacco, and shifts in the terms of

trade toward agriculture then pushed Chesapeake wealth levels up.

The wealth of the region was not evenly shared by colonists of European

ancestry. The early settlements at Jamestown and St. Mary's were marked

by high levels of inequality as both colonies were at first dominated by

ambitious, grasping men who used family fortunes and English connec-

tions to control development. Early inequalities diminished, however, as

rapid expansion under the constraints imposed by the Chesapeake system

of husbandry ushered in the small planter's age. Thereafter, inequality

rose in response to four largely sequential processes. First, farm building

created opportunities for accumulation and permitted some men to pull

ahead of their neighbors. Second, the rise of a native-born population

contributed to inequalities as inherited fortunes became a major source of

wealth and power. Third, slavery furthered the progress of inequality by

allowing some planters to command much larger work forces than had

been possible in the seventeenth century. Finally, while the diversification

of the export sector created new opportunities along the Bay, many small

planters lacked the resources to adopt the new methods and found them-

selves trapped in the old style of husbandry, unable to participate in the

wave of prosperity that followed 1750. The cumulative effect of these

processes was substantial. In the middle of the seventeenth century, at the

height of the small planter's age, the richest 10 percent of

the

families in

the tidewater owned roughly 40 percent of

the

wealth, a

figure

that was to

approach 70 percent by the eve of independence.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and Social Development of the South 271

To some extent, the progress of inequality in the tidewater was coun-

tered by the extension of the Chesapeake frontier. From the middle de-

cades of the seventeenth century to the Revolutionary era, the area of the

colonial occupation increased steadily in response to a recurring process.

Frontier opportunities - cheap land, the possibilities of farm making, and

credit supplied by land developers and merchants - attracted migrants,

especially newly freed servants and the children of poor families, to the

edge of colonial settlement. Migrants both relieved the pressures produced

by growing population in the tidewater and re-created the social structures

of the yeoman planter's age. Initially, the prospects that poor planters

could establish households and acquire land were good and levels of in-

equality low. However, rapid population growth, differential success in

farm building and inheritance, and the arrival of planters of

means,

who

moved in with substantial slave work forces as the region's potential for

development became clear, transformed the new settlement in ways that

made it increasingly like the old tidewater. As population densities grew,

land prices and inequalities rose, tenancy became more common, and

young adults left the region with growing frequency to find better pros-

pects,

thereby further extending the Chesapeake frontier.

While this process operated as a brake on inequality and preserved some

measure of opportunity in the Chesapeake region throughout the colonial

era, there is evidence of strain as the eighteenth century progressed. By

the 17

50s,

more than half the households in many tidewater counties were

established on rented lands, often with short-term leases that offered little

chance to build equity and slowly climb the agricultural ladder. Tenancy

was less common and prospects somewhat brighter in the piedmont and

on the Virginia southside, but even those regions were filling up, with

little unimproved land remaining and that too expensive for poor men to

purchase. By the 1780s, there was no longer any place in the Chesapeake

region that could be described as "good poor man's country." Poor men

and women now had to leave the area altogether, strike out for the raw

frontiers of the southern backcountry, Kentucky and Tennessee, or the

Northwest to find land and opportunity.

Any discussion of inequality must consider the rise of slavery and the

lives of African Americans. Blacks were only 2 percent of the region's

population in 1650, but their share grew steadily over the next century,

reaching 13 percent by 1700, 25 percent by 1730s, and 40 percent by

1750,

where it hovered into the nineteenth century. The rise of slavery

contributed to the growth of inequality among whites by permitting the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

272 Russell R. Menard

accumulation of great estates while clearly separating planters who worked

their fields from gentlemen who supervised others. Evidence from Prince

George's County, Maryland, a prime tobacco region on the Potomac,

documents the emerging structure. During the initial decade of the eigh-

teenth century, when slaves were first brought into the county in large

numbers, roughly one-quarter of the households owned slaves. The major-

ity held only three or fewer blacks, and there were only a handful of great

planters; perhaps 5 percent of the masters (less than 2 percent of the

household heads) owned 20 or more slaves. Although tenancy was on the

rise,

small, owner-operated farms without slaves remained the typical unit

of production in the county. By the 1770s, conditions had changed. More

than half the households owned slaves, the average size of slaveholdings

more than doubled (although it remained small by lowcountry standards),

and the number and wealth of great planters rose sharply. Perhaps the

most striking development was the near disappearance of small landown-

ers without slaves, who by then accounted for fewer than 10 percent of the

households. Slavery brought sharp distinctions to Euro-American society

in the Chesapeake, dividing it into masters who owned both land and

slaves and those who owned neither, while at the same time permitting a

few great planters to pull far ahead of their neighbors.

More important was the impact of slavery on African Americans them-

selves. Uncertainties surrounding the status of blacks in the middle de-

cades of the seventeenth century permitted a few to acquire freedom and

modest estates, but as their numbers grew, racial lines hardened into a

rigid class system, and opportunities disappeared. By the late 1670s,

when Africans began to arrive in large numbers, their fate was sealed: they

would be slaves in a harsh regime. Like white immigrants, they faced a

severe disease environment and a skewed sex ratio that limited reproduc-

tion. But their situation was worsened by isolation on small plantations,

restrictions on mobility, more rigorous work demands, the degradations of

slavery, and masters harsh enough to use dismemberment as a regular

method of

discipline,

as with Robert Carter who boasted of having "cured

many a negro of running away" by cutting off their toes.

12

Despite these brutal circumstances, blacks experienced a demographic

transition similar to that among whites as the gradual growth of an

American-born slave population led to the beginnings of reproductive

increase in the 1720s. By the eve of the Revolution, most blacks had been

" Robert Carter to Robert Jones, 10 October 1727, Virginia Magazine of History and

Biography

101

(1993),

280.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and Social Development of the South 273

born in the region, and the rate of natural population growth was high

enough to push the slave trade into sharp decline. Slavery remained harsh

and oppressive, but reproductive growth, rising population densities, and

increasing plantation sizes helped slaves to build ties of affection, family,

and friendship while permitting the articulation of a distinct African

American culture that shaped black identities and undermined the cul-

tural homogeneity of Chesapeake colonial society.

The growing inequalities in Chesapeake society are perhaps most evi-

dent at the top, in the rise of the gentry. A disruptive demographic

regime, high rates of immigration, rapid upward mobility, and con-

straints on wealth accumulation had forestalled the development of a

cohesive ruling class during the seventeenth century. Things began to

change around 1700, however, as demographic conditions permitted

longer lives, more stable families, and dense kin networks, as immigration

fell off and opportunities contracted, and as slavery allowed some to build

great plantations. The Chesapeake gentry slowly emerged as a cohesive

ruling class in the early decades of the eighteenth century. Its wealth was

based on land and slaves, its solidarity rested on shared interests nurtured

by family ties and a common culture that set them apart from the majority

of planters, its world view informed by an ideology that mixed racism,

republicanism, and patriarchalism, and its cohesiveness reinforced by the

need to control blacks and retain the cooperation of poor whites. By the

1730s, a powerful class of great planters was established in the tidewater

and was slowly extending its reach onto the Chesapeake frontier. Despite

occasional challenges to its authority - for example, the riots against to-

bacco regulation in the 1730s, and the evangelical revolt of the 1760s

—

the great planters were confident of their abilities and secure in their

position, sufficiently so to lead the region into rebellion and to play the

major role in the construction of the new nation that followed in the

rebellion's wake.

RICE AND THE RISE OF THE LOWCOUNTRY

By the beginning of the American independence movement, the rapid

growth of the lowcountry economy and the opportunities it provided had

assumed legendary dimensions. The lowcountry was "the most opulent

and flourishing" region in British North America, even "the most thriving

Country perhaps on this Globe." It was a place where a "frugal and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

274

Russell

R. Menard

industrious" white man was promised "a sure road to competency and

independence," where planters could "all get rich," and where merchants

rose "from humble and moderate Fortunes to great affluence." Contempo-

raries were amazed by lowcountry achievements, by "the rapid ascendency

of families which in less than ten years have risen from the lowest rank,

have acquired upward of £100,000, and have moreover, gained this

wealth in a simple and easy manner." Josiah Quincy's notes on Joseph

Alls ton, a Winyah Bay planter, are typical. Allston started just "a few

years ago" at 40 years of age "with only five negroes" but now had "an

immense income all of his own acquisition" resting on

five

plantations and

more than 500 slaves, which yielded a net income of £5,000 to £6,000 a

year. And, Quincy added, as if the story were not yet up to the legend, "he

is reputed much

richer.

"'3

Lowcountry wealth rested on the remarkable growth of its leading

exports, rice and indigo. Success was not immediate, however, at least by

the standards of the early colonists, many of

whom

measured their perfor-

mance against the incomes earned by sugar planters. Such expectations

were come by honestly, for the first English settlements in the lowcountry

were rooted in the Barbadian sugar revolution of the mid-seventeenth

century. By 1660, Barbados was overcrowded by American colonial stan-

dards:

its population density had reached 250 persons per square mile,

most of the arable land was occupied and cultivated, and entry costs into

sugar production were high enough to keep all but those with substantial

resources out of the planter class. Indentured servants who finished their

terms found few opportunities, and many simply left, sometimes signing

new indentures to

finance

the move - stark comment on island prospects.

By one estimate, roughly 10,000 Barbadians, most of them recently freed

servants, left the colony for other parts of British America during the

seventeenth century. An expanding market for provisions and timber

accompanied this outmigration as planters concentrated on sugar and

denuded the island of

trees,

creating opportunities for colonists elsewhere

to grow food for the large and increasing slave population and to supply

Barbados with wood for building, fuel, and cask making. By 1660,

entrepreneurs realized that by tapping the Barbadian migrant stream, the

North American coastline between the Chesapeake and Spanish Florida, as

•' For the sources of the quotations, see Russell R. Menard, "Slavery, Economic Growth, and Revolu-

tionary Ideology in the South Carolina Lowcountry," in Ronald Hoffman, John J. McCusker,

Russell R. Menard, and Peter J. Albert, eds., The

Economy

of Early

America:

The Revolutionary

Period,

'763-179° (Charlottesville, VA: 1988), 256, 268-9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and

Social Development

of the

South

275

yet unoccupied by Europeans, could be colonized, the imperial designs of

competing nations preempted, and the needs of the sugar islands for wood

and food met.

After several false starts, a permanent settlement was established on the

Ashley River in 1670, near the site of Charlestown. Although troubled by

food shortages and disease, the colony grew steadily: by 1700, it was home

to roughly 3,300 Europeans and about 2,600 African and Native Ameri-

can slaves. The first several decades were years of experimentation during

which Carolinians explored the local resource base and tested overseas

demand. In the process, they built a diverse economy by colonial stan-

dards.

Self-sufficient agriculture and form building were the major activi-

ties,

but settlers also produced exports that could be exchanged for manu-

factured goods, servants, and slaves. The early export trade centered on

the supply of provisions and wood products to Barbados (making early

Carolina a colony's colony) supplemented by a trade in furs to England.

The economy did not generate great fortunes, but it provided local mer-

chants and planters a variety of opportunities for small-scale production

and exchange.

The experimentation ended with the emergence of rice as the major

commercial product of the lowcountry early in the eighteenth century.

The industry grew rapidly at first, as exports of

a

mere 10,000 pounds in

1698 reached 6.5 million by 1720, and peaked at more than 43 million in

1740 before entering a decade of stagnation and decline. A reliable price

series is not available before the 1720s, but scattered observations suggest

a steady fall, indicating that productivity gains helped to fuel the initial

expansion. Exports rose more rapidly than prices fell, and the value of the

crop increased, from roughly £20,000 sterling around 1720 to about

£100,000 around 1740. By then, rice was one of the major exports of

British America and the dominant crop in the lowcountry, "the chief

support" of the region and "its great source of opulence," as much the

"staple Commodity" of the area "as Sugar is to Barbados or Jamaica, or

Tobacco to Virginia and Maryland."

1

''

While rice became the lowcountry staple in the early decades of the

eighteenth century, initially the growth of that industry was part of a

more general expansion, an export boom that began around 1700. Some of

that boom reflected continued growth in trades established during the

" Alexander Hewatt, An Historical

Account

of

the

Rise and

Progress

of

the Colonies

of South Carolina and

Georgia, 2 vols. (London: 1779), I, 119; [James

Glen],

A Description of

South

Carolina . . .

(London: 1761), 87.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

276 Russell R. Menard

seventeenth century, especially the production of food stuffs and timber

for the sugar islands and the shipment of deerskins to England. Much of

the boom turned on naval stores, a new set of products of little importance

before 1700. The English government, reacting to wartime disruption of

its supply from the Baltic, provided the incentive for the industry in 1705

in the form of bounties for products made in the colonies. The incentives

worked: Charlestown exports of pitch and tar exceeded 6,500 barrels in

1712,

50,000 in 1718, and peaked at nearly 60,000 in 1725.

The export boom continued until about 1740, but in its latter stages,

its character changed as planters concentrated on rice. Corn exports, for

example, reached nearly 95,000 bushels in 1735 before falling to only

15,000 in 1739. Exports of barrel staves fell by half

over

the same period,

while leather exports, a byproduct of meat production, fell by about two-

thirds from 1734 to 1739. The most important change, however, was in

the naval stores industry. Exports of pitch, tar, and turpentine peaked at

about 60,000 barrels worth perhaps £25,000 sterling in the mid-i72os.

By 1732, exports were at roughly 25,000 barrels worth £7,000; by 1739,

11,000 barrels worth less than £3,000.

The decline of the lowcountry naval stores industry is usually attributed

•

to shifts in British policy. In 1724, the government insisted that quality

standards be met before bounties were paid, and in 1729, it reduced the

premiums substantially. While it

is

true that high labor costs in

the

colonies

led producers to use methods that sacrificed quality for quantity, and that

bounties were important to the beginnings of the industry, the decline had

other

sources.

Naval stores were crowded out of the lowcountry, along with

foodstuffs and wood products for the sugar industry, being pushed to the

periphery of the plantation district, to the South Carolina backcountry, to

Georgia, and, especially, to the Cape Fear River Valley of North Carolina.

Lowcountry planters concentrated on rice, their most profitable staple, and

had little time for anything

else.

The consequences of that focus are appar-

ent in the increased specialization of the lowcountry economy revealed in

the growth of

rice

exports per capita, which rose from about 70 pounds in

1700 to 380 in 1720 and to nearly 1,000 in 1740.

The lowcountry export boom transformed coastal South Carolina, mak-

ing it into a plantation society more similar to the British Caribbean than

to the other mainland colonies. The extent of that transformation is

evident in the population of the region, especially in the growth of slavery.

The export boom led to a sharp increase in demand for labor, an increase

met largely by African slaves. Charlestown slave imports averaged 275 a

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008