Engerman S.L., Gallman R.E. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Vol. 1: The Colonial Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The

Northern

Colonies:

Economy

and

Society

kee schooners could safely operate, and provided New England settlers

with both security on their northern frontiers and a windfall of previously

cleared Acadian farmland to occupy. Then, by conquering Canada and

damaging thereby the bargaining position of the Iroquois, British military

might opened the western territories of New York and Pennsylvania to

colonial agricultural development. Most important of all was the British

Navy's long and successful campaign to achieve dominance over the North

Atlantic. Simply put, it helped to be on the winning side; the disruption

of foreign fleets and the privilege of operating under the protective wing of

the British Navy often enabled American traders and privateers to reap

windfalls from war they would otherwise have missed. By countering

French privateers, driving pirates from the seas, and paying an annual

tribute to the Barbary powers that persuaded the latter to leave British and

colonial shipping alone, the Crown and its navy made the North Atlantic

of the eighteenth century a protected arena for northern merchant trade.

Britain's struggle against France, Spain, and the Netherlands in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was

a

program of commercial aggres-

sion, conceived with little attention to the interests of her colonial posses-

sions.

Yet it was inevitable that colonial societies driven by the pursuit of

competency and possessed of commercial institutions similar to those of

the mother country would have profited too from the imperial triumph.

CONCLUSION

The northern provinces were by no means the most prosperous of Britain's

American possessions. By most measures, either in the performance of

their own economies or in their significance within the transoceanic econ-

omy, they suffered by comparison to the plantation colonies of the South.

The significance of their developments up to the outbreak of the Revolu-

tionary War, however, lay not in the quantity of growth they had achieved

but in the character of

the

economy they had acquired. Complex, mercan-

tile,

and diversified, the colonies of the Northeast had not yet begun to

industrialize, but by 1775, they did possess social structures replete with

farmers, traders, seamen, craftsmen, and a matching contingent of skilled

housewives and daughters, all of whom would later be mobilized into

domestic outwork, petty manufacturing concerns, and factory production.

Truthfully, some of the plantation colonies were also moving in the direc-

tion of diversification in the eighteenth century. But they started late, and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

248 Daniel

Vickers

the lead that their northern counterparts had gained early on in craft

production, shipping, and merchant services enabled the North to capture

much of the business that southern growth eventually did generate. In

essence, northeastern North America led the New World into the indus-

trial age, because it had come closest over its colonial history to imitating

successfully the first industrial nation of

all:

Great Britain. And paradoxi-

cally, it had done so for reasons that had in the beginning as much to do

with matters of faith and self-determination as they had with profit.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL

DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOUTH

RUSSELL R. MENARD

THE SOUTH ON THE EVE OF

INDEPENDENCE

At the eve of the American independence movement, the idea of

the

South

is an anachronism, a concept whose time is yet to come. If

by

the colonial

South one means the area bounded on the north by (roughly) the Ohio and

Susquehanna rivers, at the west by the Mississippi, and at the east and

south by the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of

Mexico,

there is little to tie

the region together. Even under more restricted definitions confined to

territory long-claimed by the British (excluding, that is, the newly ac-

quired Floridas and the French settlement at Louisiana) or the more lim-

ited region actually colonized by the British (excluding the trans-

Appalachian west), the area has little unity. In 1775, there was no "South"

with a single, integrated economy, a unifying culture, or a cohesive ruling

class with a shared vision of the future. We are best served by recognizing

diversity from the start and rejecting the notion of

a

"South" in favor of a

concept of

"Souths,"

four proximate but separate regions with distinctive

characteristics: the tobacco colonies around Chesapeake Bay; the rice and

indigo districts of the Carolina-Georgia lowcountry; an area of mixed

farming or "common husbandry" in the backcountry and around the

periphery of the plantation districts; and a frontier zone dominated by

cross-cultural trade. However, if the South was not yet a region, the

factors that would give it greater unity and define its character during the

early nineteenth century were firmly in place: an expansive plantation

agriculture, African slavery, and an emerging planter class with a sense of

purpose.

249

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

250

Russell

R. Menard

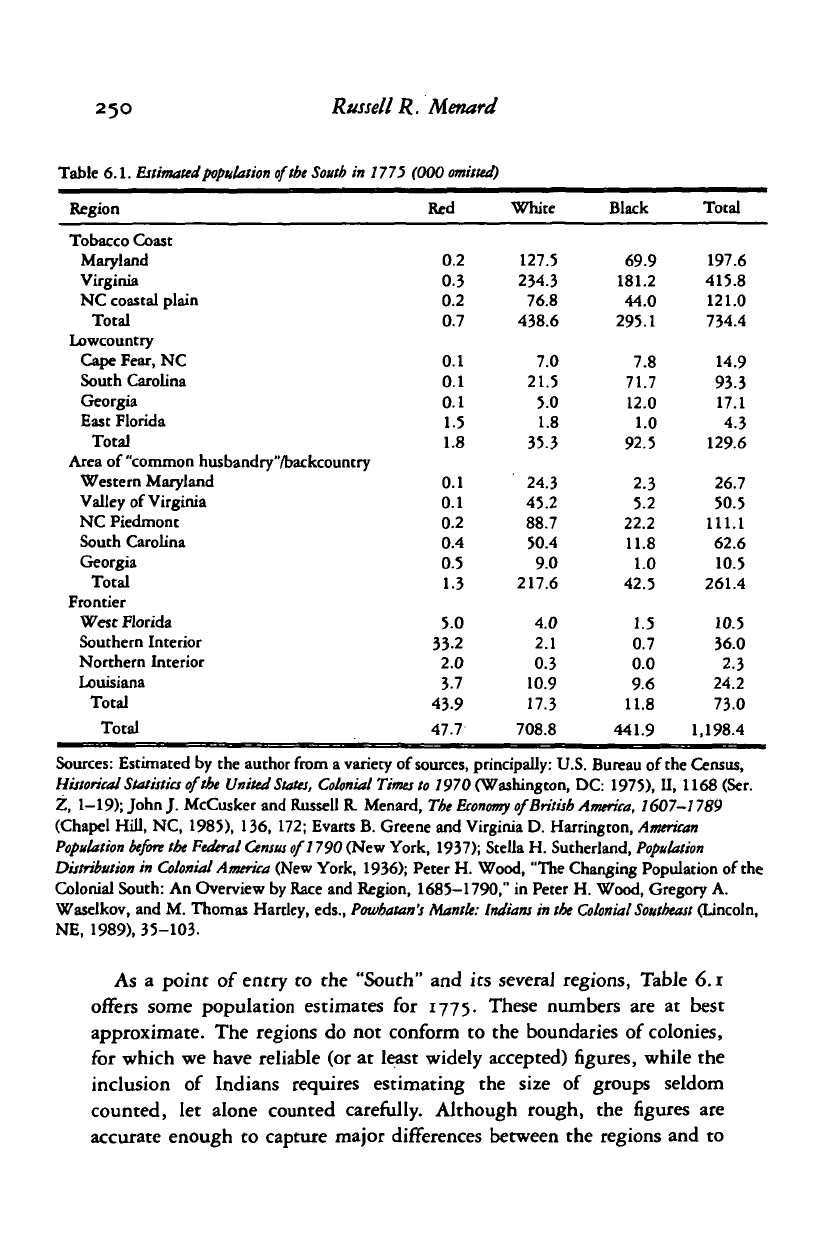

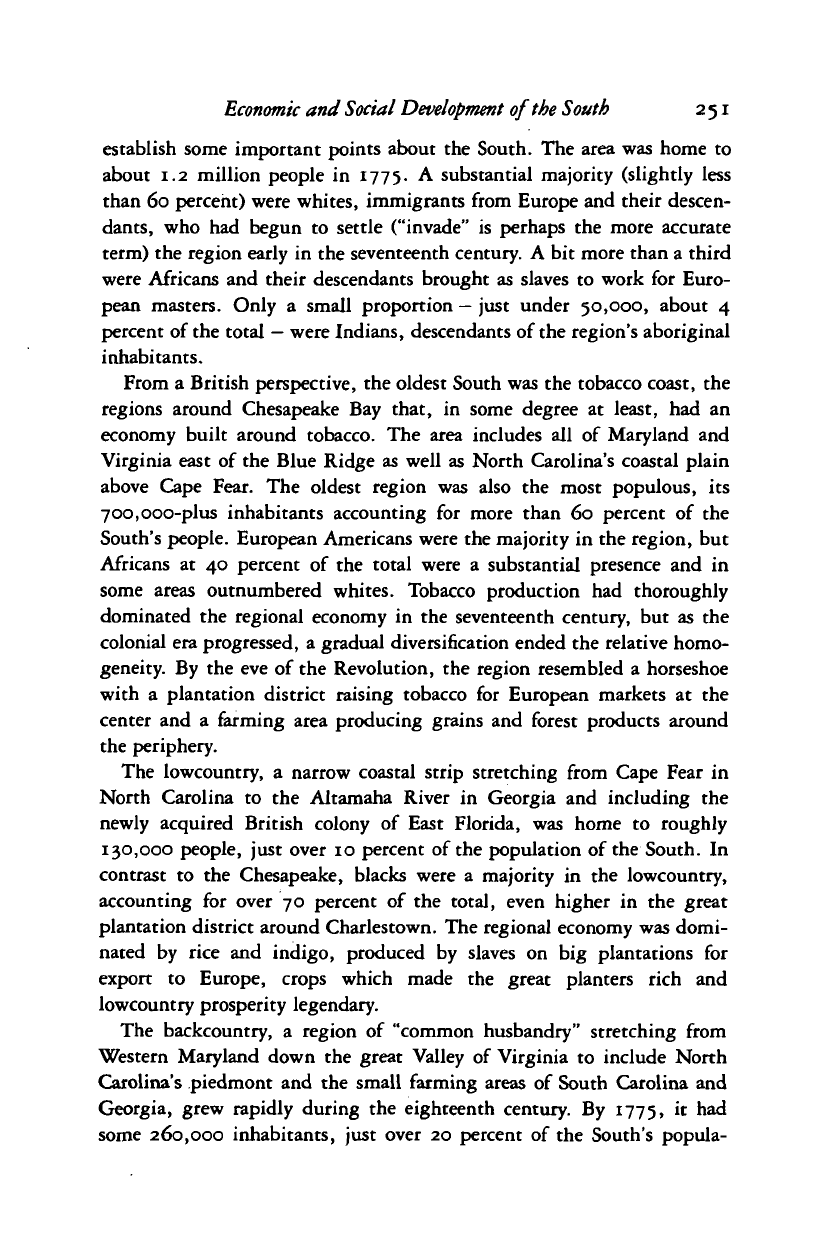

Table 6.1. Estimated population of

the South

in 1775 (000

omitted)

Region

Tobacco Coast

Maryland

Virginia

NC coastal plain

Total

Lowcountry

Cape Fear, NC

South Carolina

Georgia

East Florida

Total

Area of "common husbandry"/backcountry

Western Maryland

Valley of Virginia

NC Piedmont

South Carolina

Georgia

Total

Frontier

West Florida

Southern Interior

Northern Interior

Louisiana

Total

Total

Red

0.2

0.3

0.2

0.7

0.1

0.1

0.1

1.5

1.8

0.1

0.1

0.2

0.4

0.5

1.3

50

33-2

2.0

3.7

43-9

47.7

White

127.5

234.3

76.8

438.6

7.0

21.5

5.0

1.8

35.3

24.3

45.2

88.7

50.4

9.0

217.6

4.0

2.1

0.3

10.9

17.3

708.8

Black

69.9

181.2

44.0

295.1

7.8

71.7

12.0

1.0

92.5

2.3

5.2

22.2

11.8

1.0

42.5

1.5

0.7

0.0

9.6

11.8

441.9

Total

197.6

415.8

121.0

734.4

14.9

93.3

17.1

4.3

129.6

26.7

50.5

111.1

62.6

10.5

261.4

10.5

36.0

2.3

24.2

73.0

1,198.4

Sources: Estimated by the author from

a

variety of sources, principally: U.S. Bureau of

the

Census,

Historical

Statistics

of the United

States,

Colonial Times

to 1970 (Washington, DC: 1975), II, 1168 (Ser.

Z,

1-19);

John J. McCusker and Russell R. Menard, The

Economy

of British

America,

1607-1789

(Chapel Hill, NC, 1985), 136, 172; Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington,

American

Population before

the

Federal Census

of 1790 (New York, 1937); Stella H. Sutherland,

Population

Distribution in

Colonial America

(New York, 1936); Peter H. Wood, "The Changing Population of the

Colonial South: An Overview by Race and Region, 1685-1790," in Peter H. Wood, Gregory A.

Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hartley, eds.,

Powhatan's

Mantle:

Indians

in the

Colonial Southeast

(Lincoln,

NE,

1989), 35-103.

As a point of entry to the "South" and its several regions, Table 6.1

offers some population estimates for 1775. These numbers are at best

approximate. The regions do not conform to the boundaries of colonies,

for which we have reliable (or at least widely accepted) figures, while the

inclusion of Indians requires estimating the size of groups seldom

counted, let alone counted carefully. Although rough, the figures are

accurate enough to capture major differences between the regions and to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and

Social Development

of the

South

251

establish some important points about the South. The area was home to

about 1.2 million people in 1775. A substantial majority (slightly less

than 60 percent) were whites, immigrants from Europe and their descen-

dants,

who had begun to settle ("invade" is perhaps the more accurate

term) the region early in the seventeenth century. A bit more than a third

were Africans and their descendants brought as slaves to work for Euro-

pean masters. Only a small proportion

—

just under 50,000, about 4

percent of the total

—

were Indians, descendants of the region's aboriginal

inhabitants.

From a British perspective, the oldest South was the tobacco coast, the

regions around Chesapeake Bay that, in some degree at least, had an

economy built around tobacco. The area includes all of Maryland and

Virginia east of the Blue Ridge as well as North Carolina's coastal plain

above Cape Fear. The oldest region was also the most populous, its

700,000-plus inhabitants accounting for more than 60 percent of the

South's people. European Americans were the majority in the region, but

Africans at 40 percent of the total were a substantial presence and in

some areas outnumbered whites. Tobacco production had thoroughly

dominated the regional economy in the seventeenth century, but as the

colonial era progressed, a gradual diversification ended the relative homo-

geneity. By the eve of the Revolution, the region resembled a horseshoe

with a plantation district raising tobacco for European markets at the

center and a farming area producing grains and forest products around

the periphery.

The lowcountry, a narrow coastal strip stretching from Cape Fear in

North Carolina to the Altamaha River in Georgia and including the

newly acquired British colony of East Florida, was home to roughly

130,000 people, just over 10 percent of the population of the South. In

contrast to the Chesapeake, blacks were a majority in the lowcountry,

accounting for over 70 percent of the total, even higher in the great

plantation district around Charlestown. The regional economy was domi-

nated by rice and indigo, produced by slaves on big plantations for

export to Europe, crops which made the great planters rich and

lowcountry prosperity legendary.

The backcountry, a region of "common husbandry" stretching from

Western Maryland down the great Valley of Virginia to include North

Carolina's piedmont and the small farming areas of South Carolina and

Georgia, grew rapidly during the eighteenth century. By 1775, it had

some 260,000 inhabitants, just over 20 percent of the South's popula-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

252

Russell

R. Menard

tion.

1

In contrast to the longer-settled regions nearer the coast, slaves were

a minor part of the population, only 15 percent of the total. The region

was dominated by small, family-operated farms producing livestock and

grains for home consumption, although some of that output was shipped

to the coast. Families often made small quantities of tobacco, hemp and

flax, and forest products for export. As a region, the backcountry exhib-

ited less unity than either the lowcountry or the tobacco coast, in part

because its various segments were loosely integrated into the Atlantic

world through ties to the tidewater, but also because it was a shifting,

transitional area gradually acquiring plantation characteristics.

The frontier, a vast but sparsely settled area stretching from the

backcountry to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and the Gulf of Mexico,

was inhabited by some 73,000 people in 1775, only 6 percent of the

South's population. The region exhibited considerable diversity, with a

rapidly developing plantation district in the Mississippi delta and some

areas of small farms where the frontier receded and became backcountry.

The region's distinguishing characteristic was the large native presence.

More than 90 percent of the South's native peoples lived in this section,

principally Creeks, Cherokees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws but including

numerous smaller groups, and they accounted for more than 60 percent of

the population of

the

frontier. Despite the growing plantation district and

the pressure of European settlers, the frontier was "Indian country" in

1775,

a place where native peoples shaped the rules of exchange and where

their behavior and aspirations continued to structure the economy.

The South was overwhelmingly rural in 1775. If we use a modest

threshold of 2,000, perhaps 4 percent of the "colonial" (persons of Euro-

pean and African descent) population lived in towns; a lower threshold of

1,000 increases the proportion only to about 5 percent. While all of the

subregions were largely rural, there were notable differences. Oddly, the

frontier region, where the European presence was recent and still tenuous,

was the most urbanized. New Orleans, whose population approached

5,000

in 1775, was home to nearly 20 percent of the area's colonial

inhabitants. The tobacco coast, the oldest colonial region, may have been

the least urbanized with perhaps

3

percent of its residents living in substan-

tial towns. The backcountry displayed a level of urbanization similar to

that along the tobacco coast, but the rapid growth of Frederick and

Winchester as well as the proliferation of small towns along the Great

1

The phrase "common husbandry" is from Harry J. Carman, ed., American Husbandry (New York:

1939 [orig. publ. 1775D. 240.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Economic

and

Social

Development

of the South

253

Wagon Road suggests

a

great potential

for

town development. Roughly

12 percent

of

the lowcountry's colonial population lived

in

towns,

in

large

part because of Charlestown's rise as

a

market center but also because of its

role

as the

seat

of

government

and as a

consumer city where rich planters

gathered

to

socialize

and

spend. With 12,000 inhabitants

in 1775,

Charlestown

was by far the

South's largest city.

It was

also

the

richest,

reflecting

its

place

as the

capital

of

British North America's wealthiest

agricultural region.

The economic history

of

the South usually

is

told

as a

story

of

growth,

what Adam Smith described

as an

"advance

... to

wealth

and

great-

ness."

2

For the

most part, this essay follows convention. While that

growth was bought

at an

enormous cost

to

the region's aboriginal inhabit-

ants

and to

African slaves, Smith identified from

a

European perspective

the central theme

in

the economic history of the South during the colonial

era.

The

evidence describes

a

remarkable

and

broadly shared prosperity

among European Americans

on the

eve

of

the Revolution. Colonists were

well

fed by the

standards

of

the time, hardly surprising given

the

abun-

dance

of

land

and an

economy

in

which perhaps

85

percent

of

the labor

force worked

on

farms

and

plantations.

The

quality

of

diet

is

revealed

in

the stature

of

the population:

by the

time

of the

Revolution, southern-

born men of European ancestry were, on average, just over 5*8" tall, about

3.5 inches taller than their English counterparts, slightly taller than

northerners,

and

about

the

same height

as

Americans

who

served

in the

military during World War

II.

White southerners were also well clothed,

in

part because their lively

export economies

and

membership

in

the British Empire during the early

states

of

industrialization gave them easy access

to

English textiles. Even

families with modest incomes were able

to

acquire amenities that made

life more comfortable: good bedding, tableware

and

ceramics, sugar,

tea,

spices,

and the

like. Such high levels

of

comfort were

not

always the case.

Food

was

ample from

the

beginning,

at

least after

the

terrible "starving

times"

that afflicted several early settlements were overcome,

but the

standard

of

life remained crude

for

several decades after the initial English

invasion.

By the

mid-eighteenth century, however, there

had

been

a

con-

siderable improvement.

Improvements were less marked

in

housing,

and by

this measure, most

colonists did

not

live as well as their peers

in

the parent country. The great

1

An

Inquiry into

lit

Nature andCauses oftie

Wealth

ofNations, ed.

R. H.

Campbell,

A. S.

Skinner,

and

W. B. Todd (Oxford: 1976 [orig. pub., 1776]), II, 564.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

254 Russell R. Menard

planters of the South built in the grand style, especially in the years after

1725,

but the majority of European settlers lagged behind. Their houses

were generally small and had few rooms, lacked foundations or wood floors,

and were often of wood construction. By the

eve

of the Revolution, perhaps

only 15 percent of the housing stock in the South consisted of substantial

two-story stone structures with

stairways,

differentiated

rooms,

brick chim-

neys,

and glass windows. In the backcountry and, indeed, among most

small planters nearer the

coast,

the typical house

was

a 20' by 16' box frame

structure sided with clapboards and roofed with shingles, with a wattle and

daub chimney and a

floor

of beaten earth. Such houses had a single room or

at most two and a loft; glassless, curtainless windows with shutters to keep

out the cold; and unadorned, unpainted walls chinked with clay against the

elements. The inferiority of southern dwellings reflects the rapid growth of

population, which put great pressure on the housing stock, the scarcity of

skilled craftsmen, and the high price of labor generally, all of which made

substantial homes relatively expensive. Despite their prosperity, southern-

ers put up with houses that were crowded, poorly insulated, dark, unsafe,

and unattractive by the standards of the English-speaking world.

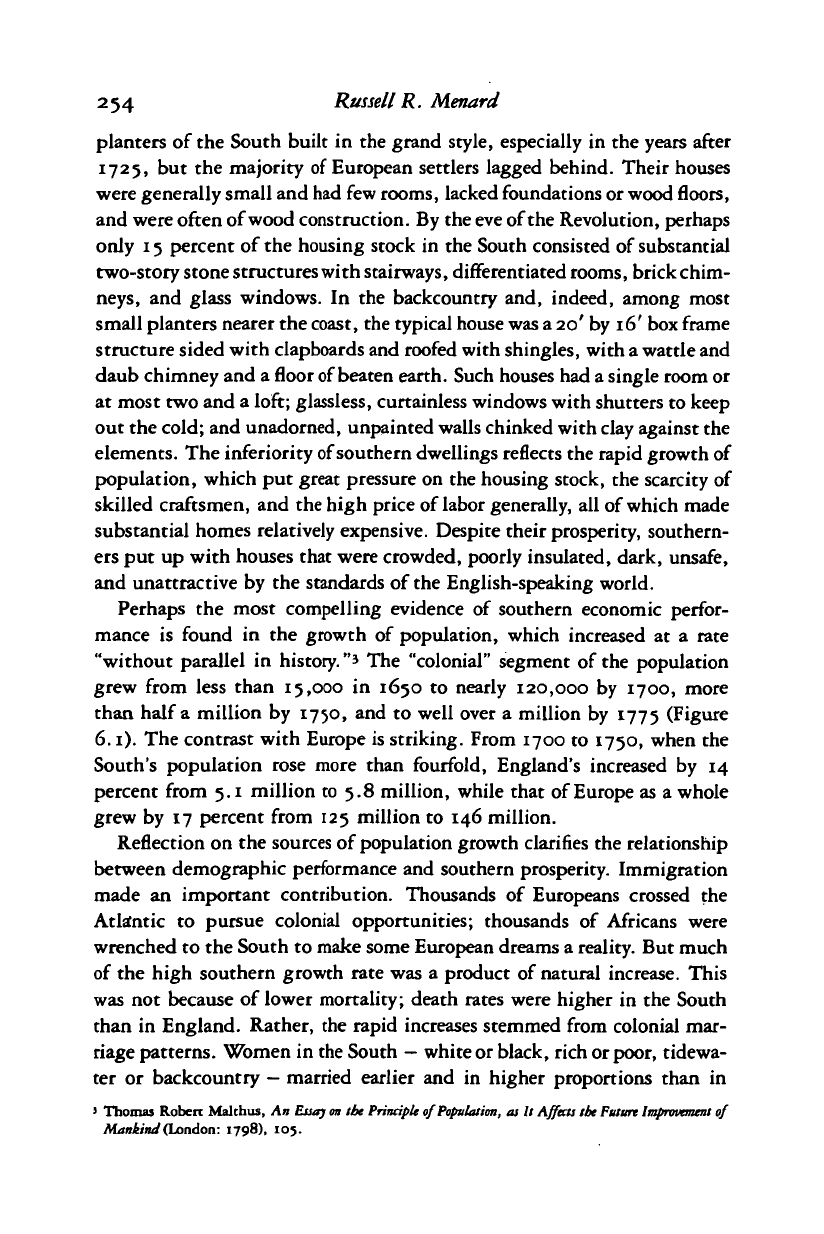

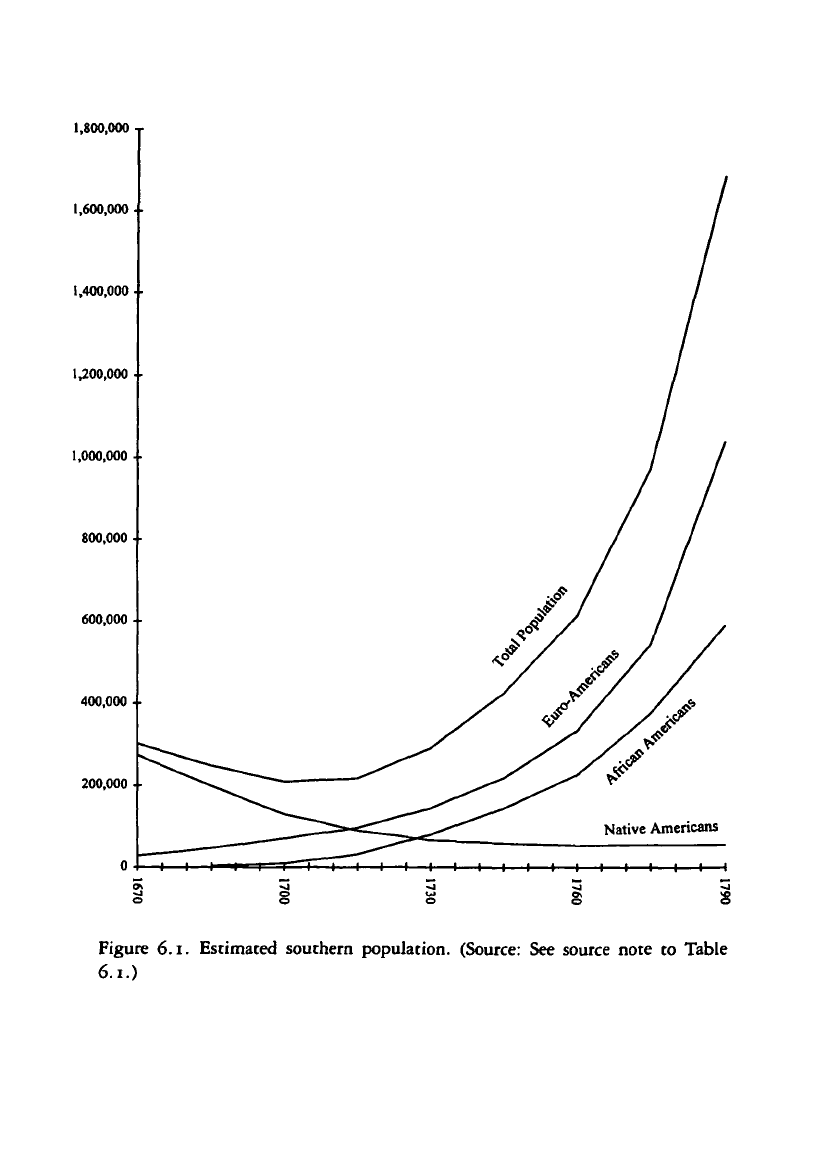

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of southern economic perfor-

mance is found in the growth of population, which increased at a rate

"without parallel in

history.

"3

The "colonial" segment of the population

grew from less than 15,000 in 1650 to nearly 120,000 by 1700, more

than half a million by 1750, and to well over a million by 1775 (Figure

6.1). The contrast with Europe is striking. From 1700 to 1750, when the

South's population rose more than fourfold, England's increased by 14

percent from 5.1 million to 5.8 million, while that of

Europe

as a whole

grew by 17 percent from 125 million to 146 million.

Reflection on the sources of population growth clarifies the relationship

between demographic performance and southern prosperity. Immigration

made an important contribution. Thousands of Europeans crossed the

Atlantic to pursue colonial opportunities; thousands of Africans were

wrenched to the South to make some European dreams a reality. But much

of the high southern growth rate was a product of natural increase. This

was not because of lower mortality; death rates were higher in the South

than in England. Rather, the rapid increases stemmed from colonial mar-

riage patterns. Women in the South

—

white or black, rich

or

poor,

tidewa-

ter or backcountry

—

married earlier and in higher proportions than in

» Thomas Robert Malchus, An

Essay on

the

Principle

of Population, as It

Affects

the Futon

Improvement of

Mankind

(London:

1798),

10;.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1,800,000

1,600,000

1,400,000

130,000

1,000,000

800,000

600,000

400,000

200,000

I 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1—) 1 1 1 1 1 1

Figure 6. i. Estimated southern population. (Source: See source note to Table

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

256 Russell R. Menard

England or the northern colonies. This distinct marriage pattern led to

larger numbers of children and played the main role in the high southern

growth rates. As contemporaries often explained, these "more general, and

more generally early" marriages were rooted in colonial prosperity, espe-

cially in the "liberal reward of labour," the abundance of land, and the

consequent "Ease and Convenience of supporting a

Family.

"*

By combining data on population size with estimates of per capita

income, it is possible to chart the size of the economy in that part of the

South that joined the American independence movement. Based on a

careful analysis of probate records, Alice Hanson Jones concluded that

per capita income in the South in 1774 ranged between £10.4 and

£12.1 sterling, or $1,145

to

I

1

.332 in 1990 dollars. Given a population

of 1.12 million and using the midpoint of Jones' range yields a gross

product for the South in 1775 of $1,387 billion (1990 dollars). With an

assumption about rates of productivity gain, it is possible to chart the

growth of the southern economy from the mid-seventeenth century to

the end of the colonial era. Table 6.2 performs such a calculation,

assuming that per capita incomes rose at 0.5 percent annually over the

125 years following 1650, a rate near the midpoint of the range for that

period suggested by recent scholarship. Under that assumption, per

capita income in the South was roughly $660 in 1650 and $935 in

1720.

In the aggregate, the economy expanded at a rate of 4.2 percent

annually over the entire period, 3.7 percent in the years following 1720.

That is an impressive performance by any standard. For the early modern

era, when stagnation and decline were more common than growth and

when even the highly successful English economy grew at only 0.5

percent per year, it is remarkable.

To a large extent, southern prosperity rested on the performance of the

export sector, especially of the major plantation crops

—

tobacco, rice, and

indigo. Together, those three crops accounted for about three-quarters of

the value of all exports from the South on the eve of the Revolution and

roughly 40 percent of the value of exports from all of Britain's continental

colonies. In per capita terms, southern exports averaged about £1.8 ster-

ling per year at the end of the colonial period, roughly twice the level

achieved by New England and the Middle Colonies. If attention is con-

fined to the free population, which, after all, controlled the resulting

' Benjamin Franklin, "Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries,

etc."

(1751), in Leonard W. Labaree et al., eds., The

Papers

of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven, CT:

I959-).

IV, 228; Smith, Wealth ofNationi, II, 565.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008