Engerman S.L., Gallman R.E. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Vol. 1: The Colonial Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

7

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL

DEVELOPMENT OF THE BRITISH

WEST INDIES, FROM SETTLEMENT

TO ca. 1850

B.

W. HIGMAN

In 1775, it was an open question whether Britain's colonies in the Carib-

bean would follow the thirteen continental colonies into independence.

The tropical colonies were integral elements in an economic system that

linked them with the North American mainland; to a large extent, they

shared common cultural and political traditions. As McCusker and

Menard comment, "The economies of the mainland and the islands were

so tightly intertwined that full understanding of development in one is

impossible without an appreciation of developments in the other."

1

At the

same time, the Caribbean colonies possessed characteristics that distin-

guished them from the English settlements to the north; it was these

features that determined their unique political and economic future.

The principal distinguishing characteristics of the British West Indian

colonial economy were its monocultural focus and dependence on external

trade, the dominance of large-scale plantations and involuntary labor sys-

tems,

the drain of wealth associated with a high ratio of absentee propri-

etorship, and the role of the servile population in the internal market.

Why these features occurred in exaggerated form in the Caribbean rather

than in other regions of the Atlantic system is an important question for

debate. The British colonies in the Caribbean were subject to an imperial

policy common to all of that state's territories, and the colonizing stock of

"settlers" was essentially the same for all of the regions occupied by the

British before the middle of the seventeenth century, the formative stage

of settlement. Thus, the role of (imperial) cultural and political factors in

1

JohnJ. McCusker and Russell R. Menard, Tbt

Economy

of British

America,

1607-1789 (Chapel Hill:

1985),

p. 145.

297

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ATLANTIC OCEAN

Gulf of Mexico

» MARTINIQUE

< ST. LUCIA

> BARBADOS

CARIBBEAN

SEA

ST.

VINCENT

'GRENADA

PACIFIC

OCEAN

The West Indies

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

British

West Indies Economic

and

Social Development

299

engendering British West Indian distinctiveness

is

likely

to

have been

insignificant.

Two aspects

of the

physical environment were crucial:

the

fact that

almost

all of

the British colonies

in the

Caribbean were

islands,

and the

tropical climate

which permitted the growth of certain crops. Islands were

particularly suited

to

development

as

export-oriented plantation econo-

mies because, with

the

available technologies

of the

early seventeenth

century, they presented great opportunities

for

occupation and territorial

control, and they minimized transportation costs by offering easy or direct

access

to

the sea. Thus, as Richard Sheridan has observed, the system was

articulated first

on the

small islands

of

the eastern Caribbean

and

later

applied to larger islands and mainland coastal and riverine areas.

2

Not only

were these small islands closer

to

Europe

and

Africa, reducing costs

of

transportation and defense, but they also possessed high ratios of coastline

to land area, which enabled plantations

to

have direct

or

cheap access

to

ocean-going ships. Thus, the early settled British sugar island of

St.

Kitts

had a ratio of 8.8 miles of coastline to every 10 square miles of area, Nevis

6.9, and Barbados 3.5.

In

St. Kitts and Nevis, the elongated plantations

were simply strung around the islands, each holding having a piece of the

coast

and a

slice

of

every possible ecological zone proceeding into

the

interior. Jamaica,

the

largest

of

the British island-colonies, had only

1.1

miles of coastline per 10 square miles of

area,

but even this ratio was high

compared to any mainland area other than the Chesapeake.

The second critical environmental factor was the tropical climate of the

Caribbean. This made possible the efficient cultivation of tropical

crops,

for

which there was

a

significant demand on the European market. Sugar was

the most important of these crops and quickly came to dominate the land-

scape. The choice

was

important, because the technological requirements of

sugar making brought

in

their train a whole series of consequences.

The emphasis placed on these physical factors in the development of the

British West Indian economy

is not

meant

to

echo

any

crude form

of

environmental determinism. Arguments

of

this type

—

purporting

to

ex-

plain the dependence on African slave labor by reference to the inability of

Europeans to perform manual work in the tropics

-

were popular elements

of the

climatic theory

of

the plantation

until about 1940.

The

more recent

historiography rightly has no place

for

such interpretations,

but the

fact

that

the

tropical Caribbean region was made

up of

fragmented, insular

• Richard

B.

Sheridan, Sugar

and

Slavery:

An

Economic

History

of

the

British

Wat

Indies, 1623-177}

(Barbados,

1974), p. 104.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

300 B. W. Higman

units rather than presenting a solid land mass to the European colonizing

class was surely significant. It permitted the development of a plantation

system in which the planter could operate in a highly independent fash-

ion, relying on long-distance trade rather than local markets and inputs,

creating a landscape in which the colonial town and merchant had only a

marginal place.

Although the analysis that follows in this essay is not intended as a

review of the historiography, emphasis will be placed on questions of

interpretation that have concerned historians of the British West Indian

economy. Most if not all of these questions have significance beyond the

region, so that the development of a Caribbean perspective must not be

seen as an indication of a creeping parochialism. In terms of theory, the

most influential has been the

plantation economy

model, designed to explain

the role of the plantation system in the Atlantic economy and the implica-

tions of that system for economic growth within the Caribbean. This

model draws on staple theory and, more particularly, ideas advanced by

Eric Williams in his seminal work,

Capitalism and

Slavery,

first

published

in 1944. Particular questions that can be linked with this set of concepts

concern the sources of capital for the plantation system, the "profitability"

of the colonies for the British Empire, the drain of wealth from the

colonies to Great Britain and the role of that capital in the Industrial

Revolution, the failure of industrialization in the colonies themselves, and

the causes of slavery and abolition.

Questions more obviously internal to the history of the region, many of

which have emerged from discussion of the larger issues, include the

reasons for the negative rate of natural increase in the West Indian slave

population (often compared to the rapid natural growth experienced in

North America); the structure and significance of the domestic economy;

the extent of internal economic diversification and of regional variations;

the role of trade with non-British imperial territories within the Carib-

bean; the chronology of plantation profitability and the decline of the

British West Indies; the significance of absentee proprietorship for social

and economic development; the variety of systems of labor domination

after emancipation; and the relationship between the free peasantry and

the protopeasantry of the

slave

period. It is issues such as these that have in

recent times provoked substantial debate within the historiography of the

British West Indies, emphasizing as they do the equal significance of

local

perspectives and events with those broader structures and external events

that made the region an integral part of the Atlantic world economy.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

British

West Indies Economic

and

Social Development

301

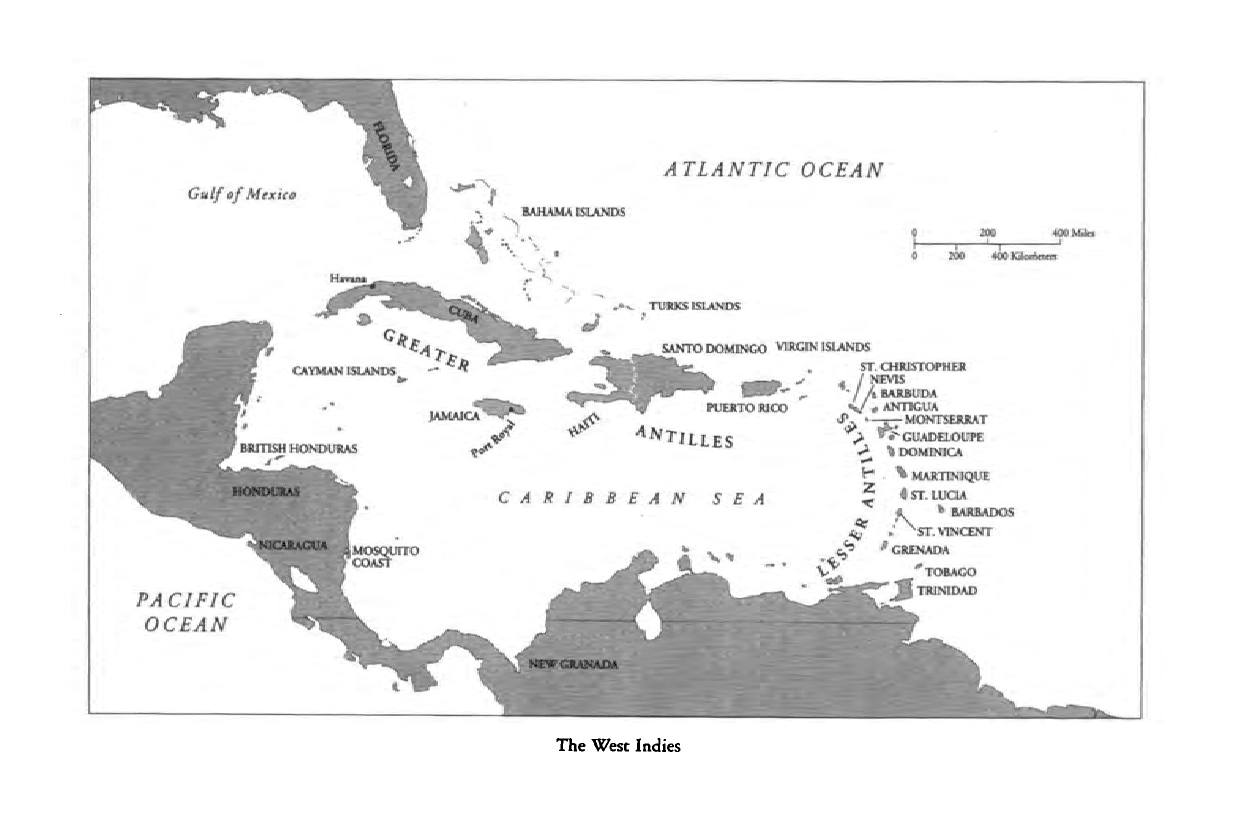

SUGAR AND SLAVERY

TERRITORIAL EXPANSION

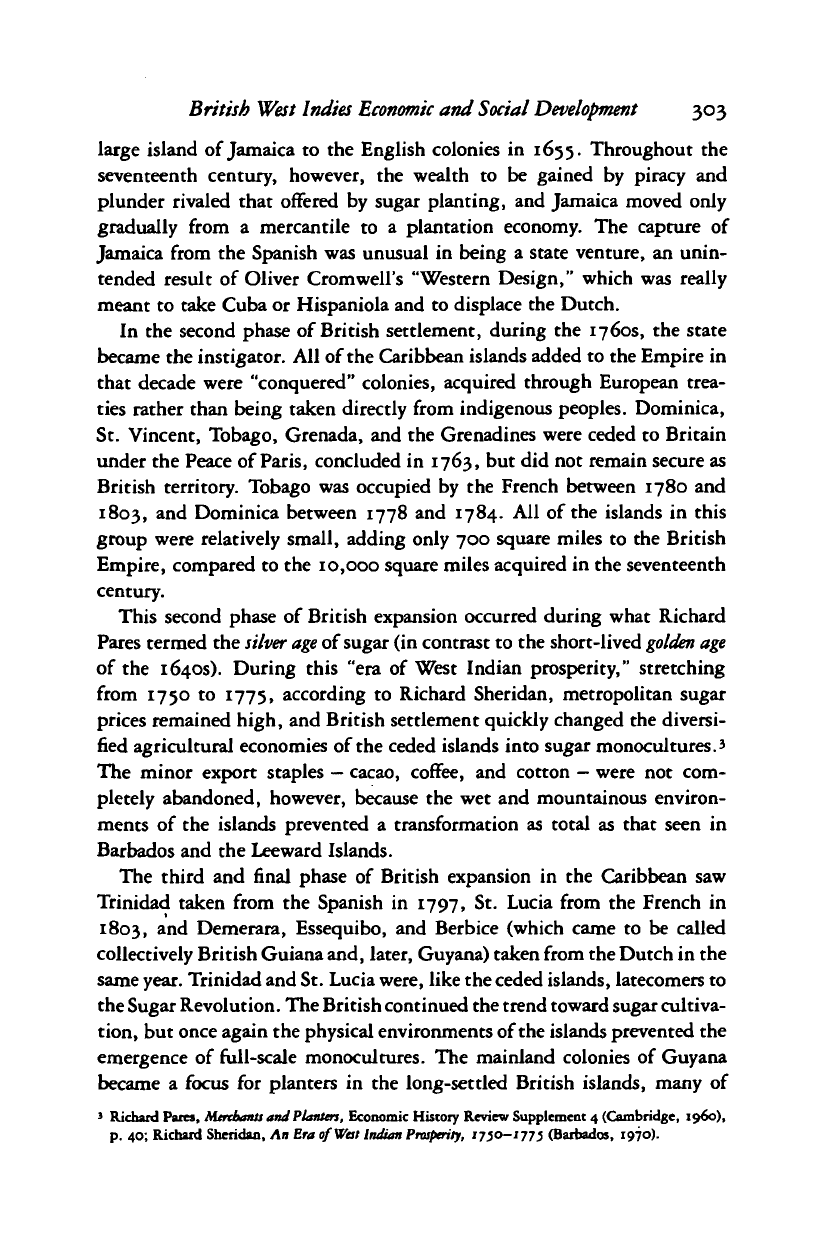

Spanish colonization of the Americas had its beginnings in the Caribbean,

but the focus of settlement was the larger western islands that provided

springboards to the mainland and the treasure of Mexico and Peru (see

map on page 298). The streams of precious metals passed through the

islands on their way to the coffers of the King of

Spain,

placing immense

temptation in the way of his European rivals. Contact with the Spanish

reduced the indigenous populations of the Greater Antilles to a mere

remnant by the middle of the sixteenth century through deliberate geno-

cide,

disease, and hard labor. The French and later the English took

advantage of the hundreds of islands and thousands of miles of sparsely

occupied coastline to engage in illicit trade with the Spanish settlements

and to raid and plunder these and the precious metals fleets themselves.

English ventures to the Caribbean began with John Hawkins in the

1560s, but it was not until the outbreak of war between England and

Spain in 1585 that privateers entered the region in numbers. Privateering,

which gave way to piracy in the seventeenth century, was an important

source of the capital required for initial settlement and the source of the

swashbuckling, risky image of the tropical plantation economies that was

to stick fast very much longer.

When the English moved from plunder to settlement in the 1620s,

they established themselves in the eastern Caribbean islands of

St.

Kitts,

Nevis,

and Barbados, far from the securely fortified western bases of the

Spanish. By that time, English as well as French and Dutch marauders had

demonstrated the vulnerability of the outlying possessions, and the Span-

ish had shown themselves unwilling to commit resources to the retention

of islands that appeared both unproductive and costly to control. For the

private colonizing parties of the English, the first settled islands held the

attractions of fertile soils suited to tobacco cultivation, safe harbors, and

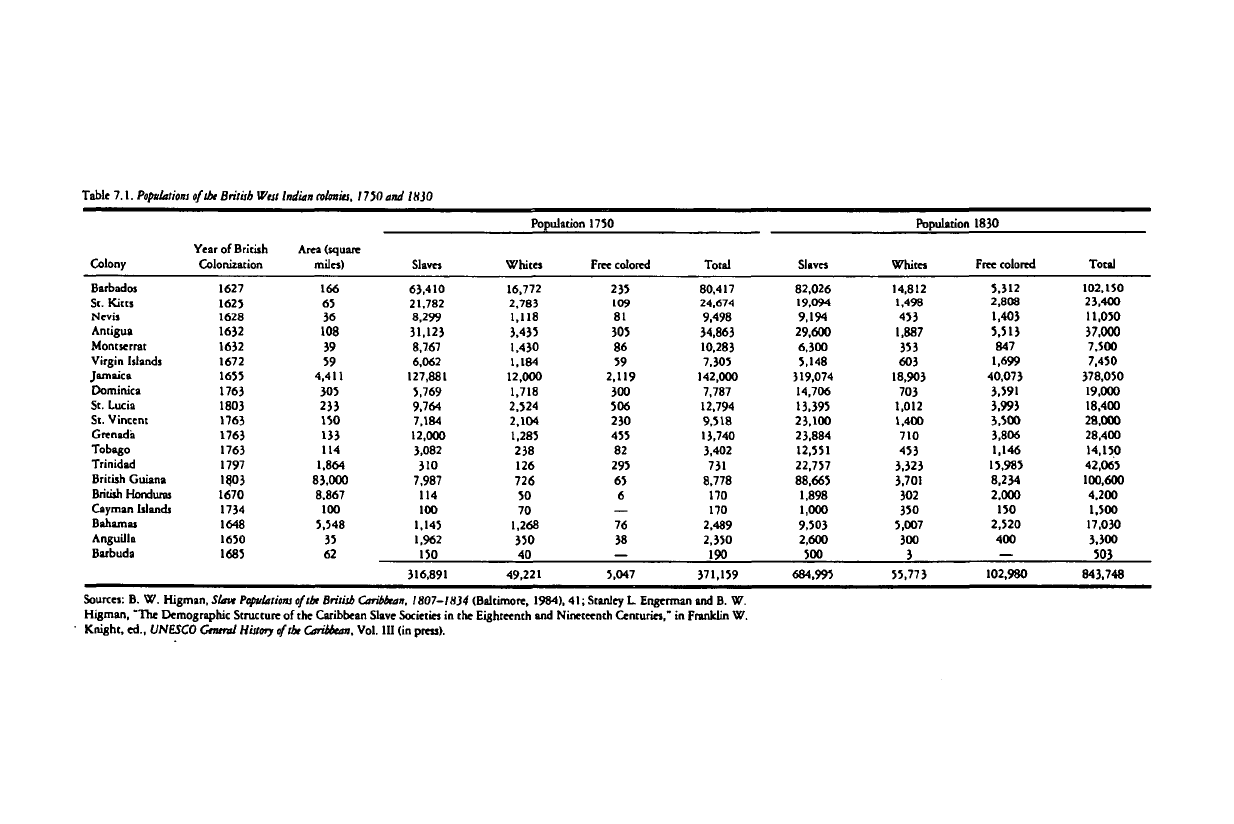

small Amerindian populations. Antigua and Montserrat were soon added

(Table 7.1). Small-scale agricultural economies were created, based largely

on tobacco cultivation and the labor of indentured white servants and

Amerindian and African

slaves.

Such fragile settlements were naturally the

subject of European rivalry

The Sugar Revolution, felt first in Barbados in the 1640s, transformed

the settlers' expectations of profit and led to the addition of the relatively

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

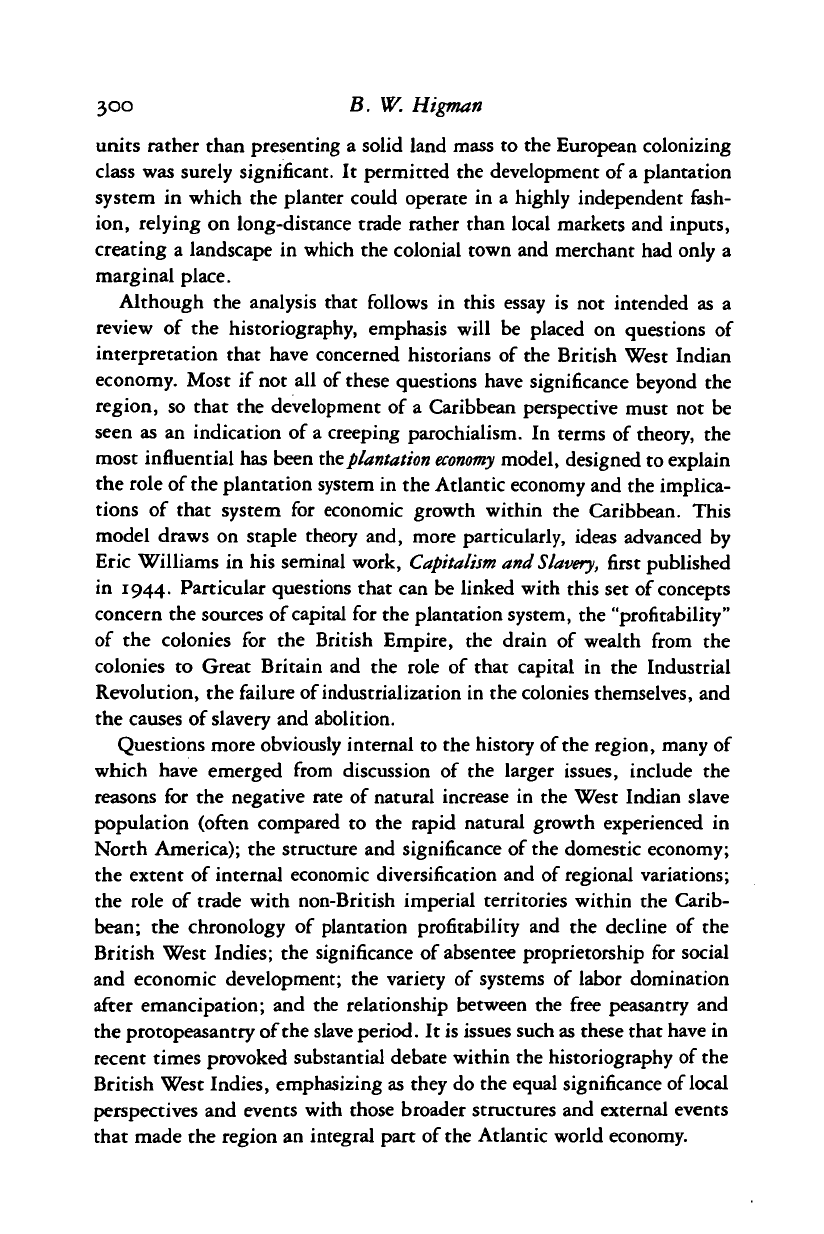

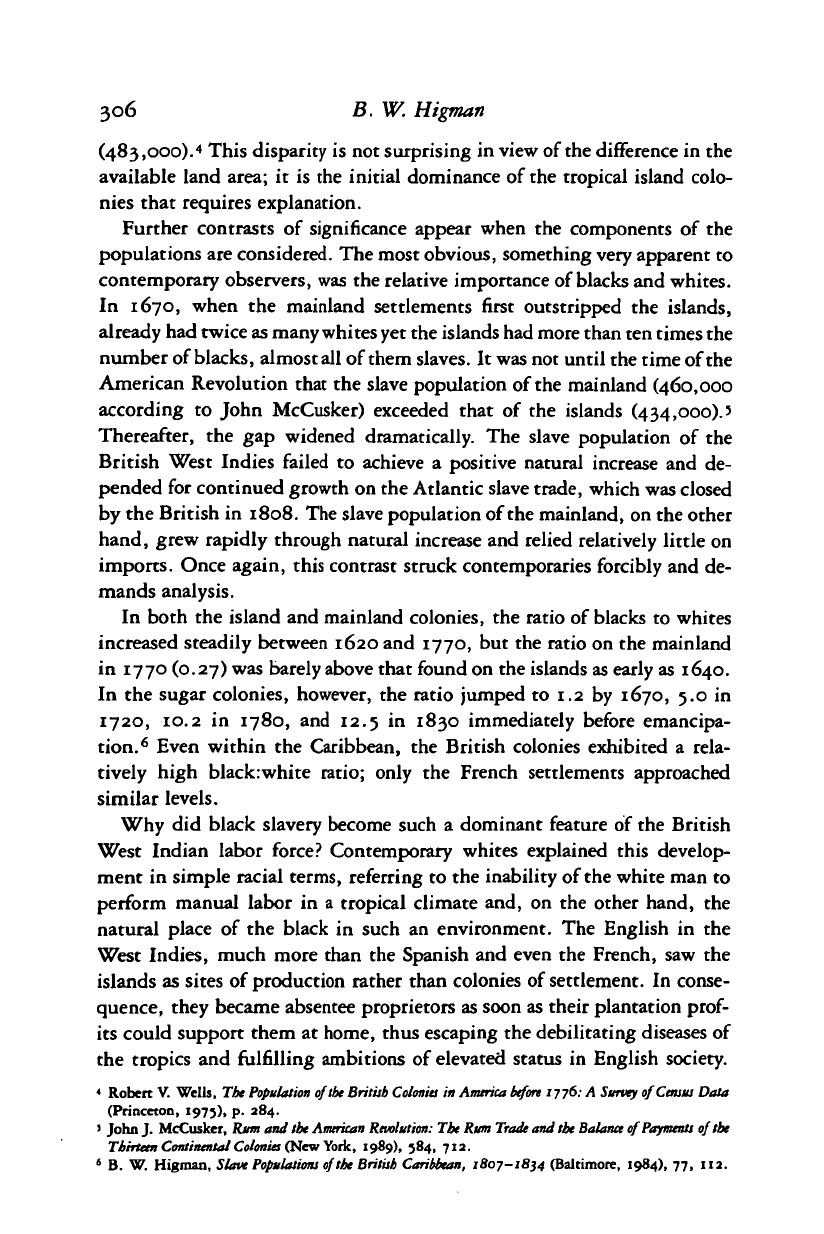

Table 7.1.

Population!

of Ox British

West Indian

colonies,

1750 and IH10

Colony

Barbados

St. Kitts

Nevis

Antigua

Montserrat

Virgin Islands

Jamaica

Dominica

St. Lucia

St. Vincent

Grenada

Tobago

Trinidad

British Guiana

British Honduras

Cayman Islands

Bahamas

Anguilla

Barbuda

Year of British

Colonization

1627

1625

1628

1632

1632

1672

1655

1763

1803

1763

1763

1763

1797

1803

1670

1734

1648

1650

1685

Area (square

miles)

166

65

36

108

39

59

4,411

305

233

150

133

114

1.864

83.000

8.867

100

5.548

35

62

Slaves

63,410

21.782

8.299

31.123

8,767

6,062

127,881

5,769

9,764

7,184

12,000

3,082

310

7,987

114

100

1,145

1,962

150

316,891

Population

Whites

16,772

2,783

1,118

3,435

1,430

1,184

12,000

1,718

2.524

2.104

1,285

238

126

726

50

70

1,268

350

40

49,221

1750

Free colored

235

109

81

305

86

59

2.119

300

506

230

455

82

295

65

6

—

76

38

—

5,047

Total

80,417

24.674

9,498

34,863

10,283

7.305

142,000

7,787

12,794

9,518

13,740

3,402

731

8,778

170

170

2,489

2,350

190

371,159

Slaves

82,026

19,094

9,194

29,600

6,300

5,148

319,074

14,706

13,395

23,100

23,884

12,551

22,757

88,665

1,898

1,000

9,503

2,600

500

684,995

Population

Whites

14,812

1,498

453

1,887

353

603

18,903

703

1,012

1,400

710

453

3,323

3,701

302

350

5,007

300

3

55,773

1830

Free colored

5,312

2,808

1,403

5,513

847

1,699

40,073

3,591

3,993

3,500

3,806

1,146

15,985

8,234

2.000

150

2,520

400

—

102,980

Total

102,150

23,400

11,050

37,000

7.500

7,450

378,050

19,000

18,400

28,000

28,400

14,150

42,065

100,600

4.200

1,500

17,030

3,300

503

843,748

Sources: B. W. Higman,

Slave Populations

oftbt British Caritbtan. 1807-18)4 (Baltimore, 1984), 41; Stanley L. Engerman and B. W.

Higman, "The Demographic Structure of the Caribbean Slave Societies in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries," in Franklin W.

Knight, ed.,

UNESCO

Cmtral

History

oftbt

Caribbean,

Vol. Ill (in press).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

British West Indies

Economic

and Social Development 303

large island of Jamaica to the English colonies in 1655. Throughout the

seventeenth century, however, the wealth to be gained by piracy and

plunder rivaled that offered by sugar planting, and Jamaica moved only

gradually from a mercantile to a plantation economy. The capture of

Jamaica from the Spanish was unusual in being a state venture, an unin-

tended result of Oliver Cromwell's "Western Design," which was really

meant to take Cuba or Hispaniola and to displace the Dutch.

In the second phase of British settlement, during the 1760s, the state

became the instigator. All of the Caribbean islands added to the Empire in

that decade were "conquered" colonies, acquired through European trea-

ties rather than being taken directly from indigenous peoples. Dominica,

St. Vincent, Tobago, Grenada, and the Grenadines were ceded to Britain

under the Peace of

Paris,

concluded in 1763, but did not remain secure as

British territory. Tobago was occupied by the French between 1780 and

1803,

and Dominica between 1778 and 1784. All of the islands in this

group were relatively small, adding only 700 square miles to the British

Empire, compared to the 10,000 square miles acquired in the seventeenth

century.

This second phase of British expansion occurred during what Richard

Pares termed the

silver age

of sugar (in contrast to the short-lived

golden age

of the 1640s). During this "era of West Indian prosperity," stretching

from 1750 to 1775, according to Richard Sheridan, metropolitan sugar

prices remained high, and British settlement quickly changed the diversi-

fied agricultural economies of the ceded islands into sugar monocultures.

3

The minor export staples

—

cacao, coffee, and cotton

—

were not com-

pletely abandoned, however, because the wet and mountainous environ-

ments of the islands prevented a transformation as total as that seen in

Barbados and the Leeward Islands.

The third and final phase of British expansion in the Caribbean saw

Trinidad taken from the Spanish in 1797, St. Lucia from the French in

1803,

an

d Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice (which came to be called

collectively British Guiana

and,

later, Guyana) taken from the Dutch in the

same

year.

Trinidad and St. Lucia were, like the ceded islands, latecomers to

the

Sugar

Revolution. The British continued the trend toward sugar cultiva-

tion,

but once again the physical environments of the islands prevented the

emergence of full-scale monocultures. The mainland colonies of Guyana

became a focus for planters in the long-settled British islands, many of

3

Richard Pares,

Merchants

and

Planters,

Economic History Review Supplement 4 (Cambridge, i960),

p.

40; Richard Sheridan, An Era of Wat Indian

Prosperity,

1750-177} (Barbados, 1970).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

304 B. W. Higman

whom moved their slaves to plantations on the rich coastal

soils.

For a brief

period, these colonies became the largest producers of cotton and coffee in

the British Empire, but they were forced to retreat as sugar was promoted

and United States cotton came to dominate the market. The total land area

added to the Empire in this final phase was large (Table 7.1), but the

effective area of settlement was limited to the coastal and riverine zones of

Guyana, making the gross amount misleading.

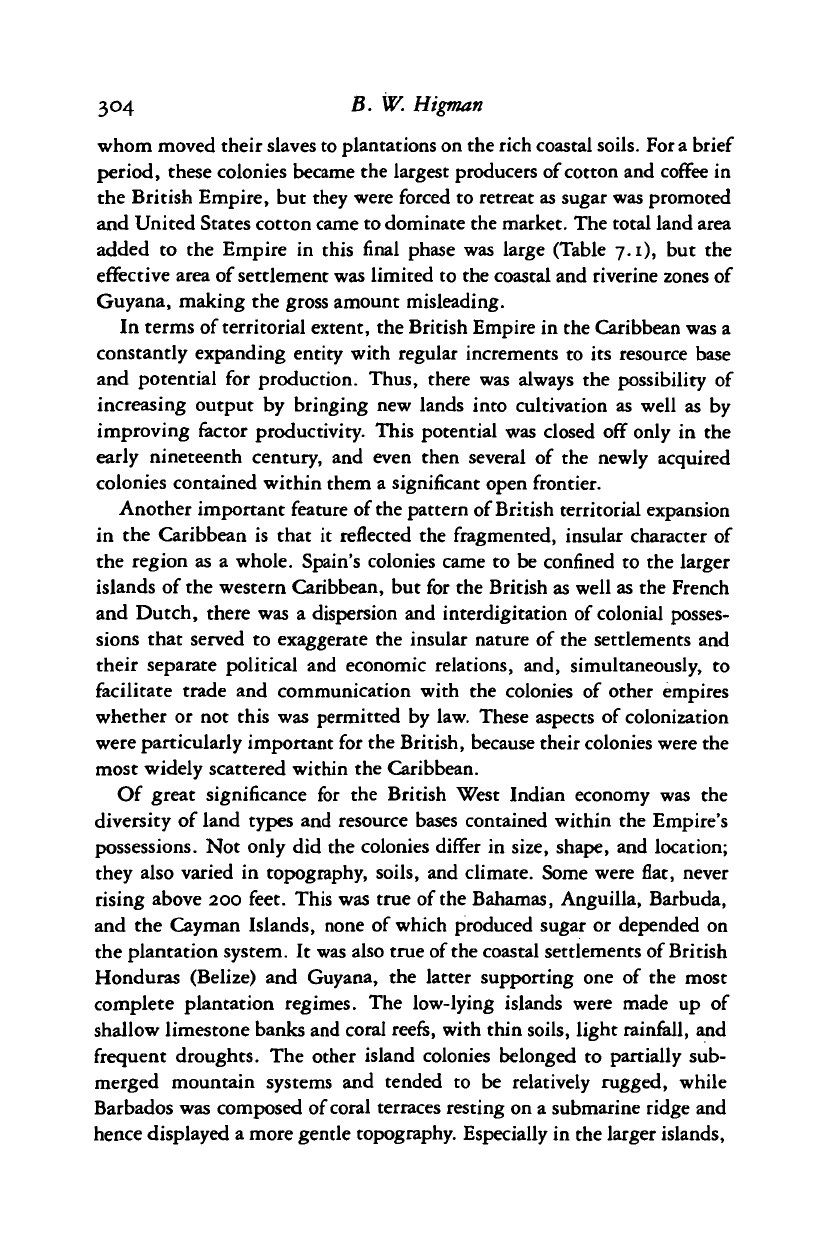

In terms of territorial extent, the British Empire in the Caribbean was a

constantly expanding entity with regular increments to its resource base

and potential for production. Thus, there was always the possibility of

increasing output by bringing new lands into cultivation as well as by

improving factor productivity. This potential was closed off only in the

early nineteenth century, and even then several of the newly acquired

colonies contained within them a significant open frontier.

Another important feature of the pattern of British territorial expansion

in the Caribbean is that it reflected the fragmented, insular character of

the region as a whole. Spain's colonies came to be confined to the larger

islands of the western Caribbean, but for the British as well as the French

and Dutch, there was a dispersion and interdigitation of colonial posses-

sions that served to exaggerate the insular nature of the settlements and

their separate political and economic relations, and, simultaneously, to

facilitate trade and communication with the colonies of other empires

whether or not this was permitted by law. These aspects of colonization

were particularly important for the British, because their colonies were the

most widely scattered within the Caribbean.

Of great significance for the British West Indian economy was the

diversity of land types and resource bases contained within the Empire's

possessions. Not only did the colonies differ in size, shape, and location;

they also varied in topography, soils, and climate. Some were flat, never

rising above 200 feet. This was true of the Bahamas, Anguilla, Barbuda,

and the Cayman Islands, none of which produced sugar or depended on

the plantation system. It was also true of

the

coastal settlements of British

Honduras (Belize) and Guyana, the latter supporting one of the most

complete plantation regimes. The low-lying islands were made up of

shallow limestone banks and coral reefs, with thin soils, light rainfall, and

frequent droughts. The other island colonies belonged to partially sub-

merged mountain systems and tended to be relatively rugged, while

Barbados was composed of coral terraces resting on a submarine ridge and

hence displayed a more gentle topography. Especially in the larger islands,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

British West Indies

Economic

and Social Development 305

such as Jamaica, the internal variety of topography, soil, and climate was

great.

POPULATION AND LABOR

The population history of the British West Indies until 1850 was a prod-

uct of the plantation system's demand for labor. In the initial stages of

settlement, before the Sugar Revolution, it seemed the islands might

follow the same course as the mainland colonies. The Sugar Revolution

dramatically altered that trajectory, creating a population dominated by

African slaves, in which the white component declined persistently and

the mixed or "coloured" sector grew. Both the African and the white

populations depended on immigration to sustain their numbers

—

forced

migration through the Atlantic slave trade in the case of

the

Africans, and

a mixture of voluntary and involuntary movements in the case of the

whites.

Only in the later phases of British expansion in the Caribbean did

colonization begin with

a

substantial existing population. The small Amer-

indian communities of the Leeward Islands were sometimes enslaved but

were more often the subject of genocide. One reason why Barbados was so

attractive to the English was that it was uninhabited at the time of

settlement. The Amerindian population of Jamaica had been almost com-

pletely destroyed as a result of the encounter with the Spanish, and the

smallness of the slave and free population facilitated the island's capture by

the English. Amerindians made up larger proportions of the populations

found in the Windward Islands, Trinidad, and Guyana, but in no case did

they have a significant impact on the overall pattern of growth. On the

other hand, the established French, Dutch, and Spanish settler popula-

tions of the colonies acquired late by the British, and more importantly

their slave populations, provided a substantial base and tended to be more

influential culturally.

British territorial expansion in the Caribbean did not mean an increas-

ing share of the region's population or of that of the British Empire in the

Americas. Rather, the British West Indian population reached an early

peak on these indicators and experienced a steady relative decline from

about 1700. The islands did have a larger population than the mainland

colonies until the 1660s but then quickly slipped behind; by 1775, the

colonies that joined the Revolution had more than four times as many

people (2,204,500 according to Robert Wells) as the British West.Indies

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

306 B. W.

Higman

(483,00c).

4

This disparity is not surprising in view of the difference in the

available land area; it is the initial dominance of the tropical island colo-

nies that requires explanation.

Further contrasts of significance appear when the components of the

populations are considered. The most obvious, something very apparent to

contemporary observers, was the relative importance of blacks and whites.

In 1670, when the mainland settlements first outstripped the islands,

already had twice

as

many whites yet the islands had

more

than ten times the

number of blacks, almost

all

of them

slaves.

It was not until the time of the

American Revolution that the slave population of the mainland (460,000

according to John McCusker) exceeded that of the islands (434,000).'

Thereafter, the gap widened dramatically. The slave population of the

British West Indies failed to achieve a positive natural increase and de-

pended for continued growth on the Atlantic slave trade, which was closed

by the British in 1808. The slave population of the mainland, on the other

hand, grew rapidly through natural increase and relied relatively little on

imports. Once again, this contrast struck contemporaries forcibly and de-

mands analysis.

In both the island and mainland colonies, the ratio of blacks to whites

increased steadily between 1620 and 1770, but the ratio on the mainland

in 1770 (0.27) was barely above that found on the islands as early as 1640.

In the sugar colonies, however, the ratio jumped to 1.2 by 1670, 5.0 in

1720,

10.2 in 1780, and 12.5 in 1830 immediately before emancipa-

tion.

6

Even within the Caribbean, the British colonies exhibited a rela-

tively high blackrwhite ratio; only the French settlements approached

similar levels.

Why did black slavery become such a dominant feature of the British

West Indian labor force? Contemporary whites explained this develop-

ment in simple racial terms, referring to the inability of

the

white man to

perform manual labor in a tropical climate and, on the other hand, the

natural place of the black in such an environment. The English in the

West Indies, much more than the Spanish and even the French, saw the

islands as sites of production rather than colonies of settlement. In conse-

quence, they became absentee proprietors as soon as their plantation

prof-

its could support them at home, thus escaping the debilitating diseases of

the tropics and fulfilling ambitions of elevated status in English society.

< Robert V. Wells, The Population of

the

British

Colonies

in America

before

1776: A

Survey

of

Census

Data

(Princeton, 1975), p. 284.

' John J. McCusker, Rum and the

American

Revolution:

The Rum Trade and

the Balance

of

Payments

of the

Thirteen Continental

Colonies

(New York, 1989), 384, 712.

6

B. W. Higman, Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 7807-1834 (Baltimore, 1984), 77, 112.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008