Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 1: To 1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Colonial Empires and Revolution

in the Western Hemisphere

Q

Focus Question: How did Spain and Portugal

administer their American colonies, and what were the

main characteristics of Latin American society in the

eighteenth century?

The colonial empires in the Western Hemisphere were an

integral part of the European economy in the eighteenth

century and became entangled in

the conflicts of the European

states. Nevertheless, the colonies of

Latin America and British North

America were developing along

lines that sometimes differed sig-

nificantly from those of Europe.

The Society of Latin America

In the sixteenth century, Portugal

came to dominate Brazil while

Spain established a colonial em-

pire in the Western Hemisphere

that included Central America,

most of South America, and parts

of North America. Within the

lands of Central and South

America, a new civilization arose

that we have come to call Latin

America (see Map 18.1).

Latin America was a multira-

cial society. Already by 1501,

Spanish rulers allowed intermar-

riage between E uropeans and native

American Indians, whose offspring

became known as mestizos. In

addition, over a period of three

centuries, possibly as many as 8

million African slaves were

brought to Spanish and Portu-

guese America to work the plan-

tations. Mulattoes---the offspring

of Africans and whites---joined

mestizos and descendants of

whites, Africans, and native In-

dians to produce a unique multi-

racial society in Latin America.

The Economic Foundations Both

the Portuguese and the Spanish

sought to profit from their colo-

nies in Latin America. One source

of wealth came from the abundant supplies of gold and

silver. The Spaniards were especially successful, finding

supplies of gold in the Caribbean and New Granada

(Colombia) and silver in Mexico and the viceroyalty of

Peru. Most of the gold and silver was sent to Europe, and

little remained in the Americas to benefit the people

whose labor had produced it.

Although the pursuit of gold and silver offered

prospects of fantastic wealth, agriculture proved to be a

more abiding and more rewarding source of prosperity

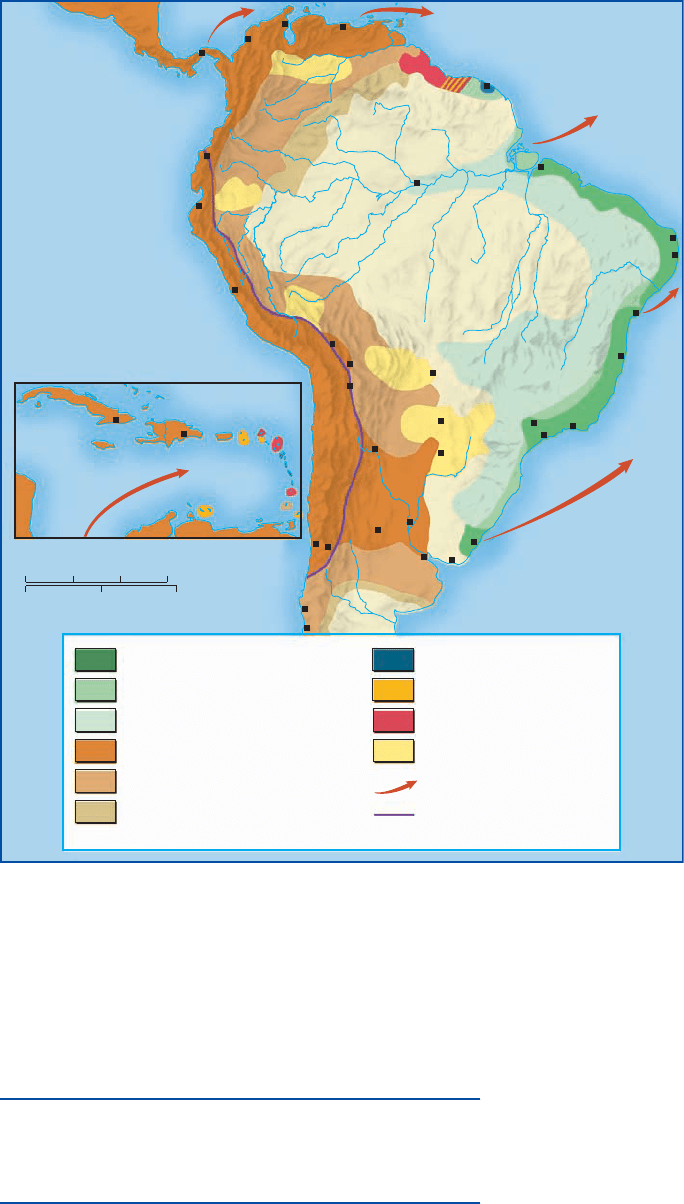

0 500 1,000 Miles

0 500 1,000 1,500 Kilometers

Portuguese colonized by 1640

Portuguese colonized by 1750

Portuguese frontier lands, 1750

Spanish colonized by 1640

Spanish colonized by 1750

Spanish frontier lands, 1750

French colonies

Dutch colonies

English colonies

Jesuit mission states

Routes of colonial trade

Extent of Inka Empire

in 1525

Pacific

Ocean

Atlantic

Ocean

Atlantic

Ocean

Caracas

(1567)

Maracaibo

Cartagena

(1532)

Quife

(1534)

Tumbes

(1526)

Lima

(1535)

Buenos Aires

(1536)

Montevideo

Rio Grande

Cordoba

(1573)

Santa Fe

Santos

(1545)

São Paulo

(1532)

Asunción

(1537)

Concepción

Rio de Janeiro

Porto Seguro

Bahia

Olinda

Recife

Belém do Para

(1616)

Cayenne

(1674)

Manáus

(1674)

(1638)

(1684)

(1691)

(1609)

Osorno

Valdivia

(1552)

Valparaiso

(1541)

Panama

(1519)

COCOA

GOLD

MERCURY

HIDES

SILVER

COPPER

SUGAR

COTTON

La Paz

La Plata(1538)

Potosí (1545)

Santiago

del Estero

Santiago (1542)

Coramba

MATTO GROSSO

MINAS

GERAES

GOLD

TOBACCO

Trinidad (1498)

A

m

a

z

o

n

R.

Tobago (1632-54)

Guadeloupe (1635)

Martinique (1635)

(1635)

(1627)

Curacao (1634)

Virgin Is.

(1648)

Santiago

(1514)

Santiago

Jamaica

(1509)

Anguilla

(1650)

Saint Martin (1648)

SUGAR

PEARLS

Hispaniola

Santo

Domingo

(1496)

A

n

d

e

s

M

t

s

.

MAP 18.1 Latin America in the Eighteenth Century. In the eighteenth century, Latin

America was largely the colonial preserve of the Spanish, although Portugal continued to

dominate Brazil. The Latin American colonies sup plied the Spanish and Portuguese with

gold, silver, sugar, tobacco, cotton, and animal hides.

Q

How do you explain the ability of Eur opeans to dominate such large areas of Latin America?

444 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

for Latin America. A noticeable feature of Latin American

agriculture was the dominant role of the large landowner.

Both Spanish and Portuguese landowners created im-

mense estates, which left the Indians either to work as

peons---native peasants permanently dependent on the

landowners---on the estates or to subsist as poor farmers

on marginal lands. This system of large landowners and

dependent peasants has remained one of the persistent

features of Latin American society. By the eighteenth

century, both Spanish and Portuguese landowners were

producing primarily for sale abroad.

Trade was another avenue for the economic exploi-

tation of the American colonies. Latin American colonies

became sources of raw materials for Spain and Portugal as

gold, silver, sugar, tobacco, diamonds, animal hides, and a

number of other natural products made their way to

Europe. In turn, the mother countries supplied their

colonists with manufactured goods.

The State and the Church in Colonial Latin America

Portuguese Brazil and Spanish America were colonial

empires that lasted more than three hundred years. The

difficulties of communication and travel between the

Americas and Europe made it almost impossible for

the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs to provide close

regulation of their empires, so colonial officials in Latin

America had considerable autonomy in implementing

imperial policies. Nevertheless, the Iberians tried to keep

the most important posts of colonial government in the

hands of Europeans.

Starting in the mid-sixteenth century, the Portu-

guese monarchs began to assert control over Brazil by

establishing the position of governor-general. To rule

Spain’s American empire, the Spanish kings appointed

viceroys, the first of which wa s established for New

Spain (Mexico) in 1535. Another viceroy was appointed

for Peru in 1543. In the eighteenth century, two addi-

tional viceroyalties---New Granada and La Plata---were

added. Viceroyalties were in turn subdivided into smaller

units. All of the major government positions were held

by Spaniards.

From the beginning of their conquest of lands in the

Western Hemisphere, Spanish and Portuguese rulers were

determined to convert the indigenous peoples to Chris-

tianity. This policy gave the Roman Catholic Church an

important role to play in the Americas---one that added

considerably to church power. Catholic missionaries

fanned out to different parts of the Spanish Empire. To

facilitate their efforts, missionaries brought Indians to-

gether into villages where the natives could be converted,

taught trades, and encouraged to grow crops. The mis-

sions enabled the missionaries to control the lives of the

Indians and keep them docile.

The Catholic church also built hospitals, orphanages,

and schools that instructed Indian students in the rudi-

ments of reading, writing, and arithmetic. The church

also provided outlets for women other than marriage.

Nunneries were places of prayer and quiet contemplation,

but women in religious orders, many of them of aristo-

cratic background, often lived well and operated outside

their establishments by running schools and hospitals.

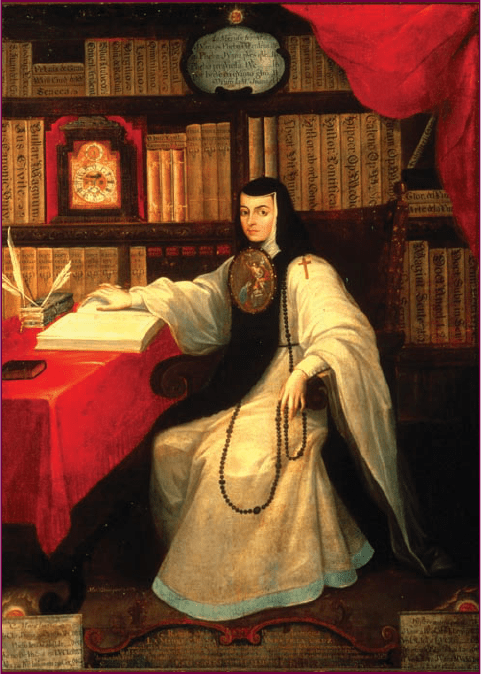

Indeed, one of these nuns, Sor Juana In

es de la Cruz

(1651--1695), was one of seventeenth-century Latin

America’s best-known literary figures. She wrote poetry

and prose and urged that women be educated.

British Nor th America

In the eighteenth century, Spanish power in the Western

Hemisphere was increasingly challenged by the British.

Sor Juana In

es de la Cruz. Nunneries in colonial Latin America

gave women—especially upper-class women—some opportunity for

intellectual activity. As a woman, Juana In

es de la Cruz was denied

admission to the University of Mexico. Consequently, she entered a

convent, where she wrote poetry and plays until her superiors forced her

to focus on less worldly activities.

c

Schalkwijk/Art Resource, NY

COLONIAL EMPIRES AND REVOLUTIONINTHEWESTERN HEMIS PHERE 445

(The United Kingdom of Great Britain came into exis-

tence in 1707, when the governments of England and

Scotland were united; the term British came into use to

refer to both English and Scots.) In eighteenth-century

Britain, the king or queen and Parliament shared power,

with Parliament gradually gaining the upper hand. The

monarch chose ministers who were responsible to the

crown and who set policy and guided Parliament. Par-

liament had the power to make laws, levy taxes, pass

budgets, and indirectly influence the monarch’s ministers.

The increase in trade and industry led to a growing

middle class in Britain that favored expansion of trade

and world empire. These people found a spokesman in

William Pitt the Elder, who became prime minister in

1757 and expanded the British Empire by acquiring

Canada and India in the Seven Years’ War.

The American Revolution At the end of the Seven Years’

War in 1763, Great Britain had become the world’s greatest

colonial power. In North America, Britain controlled

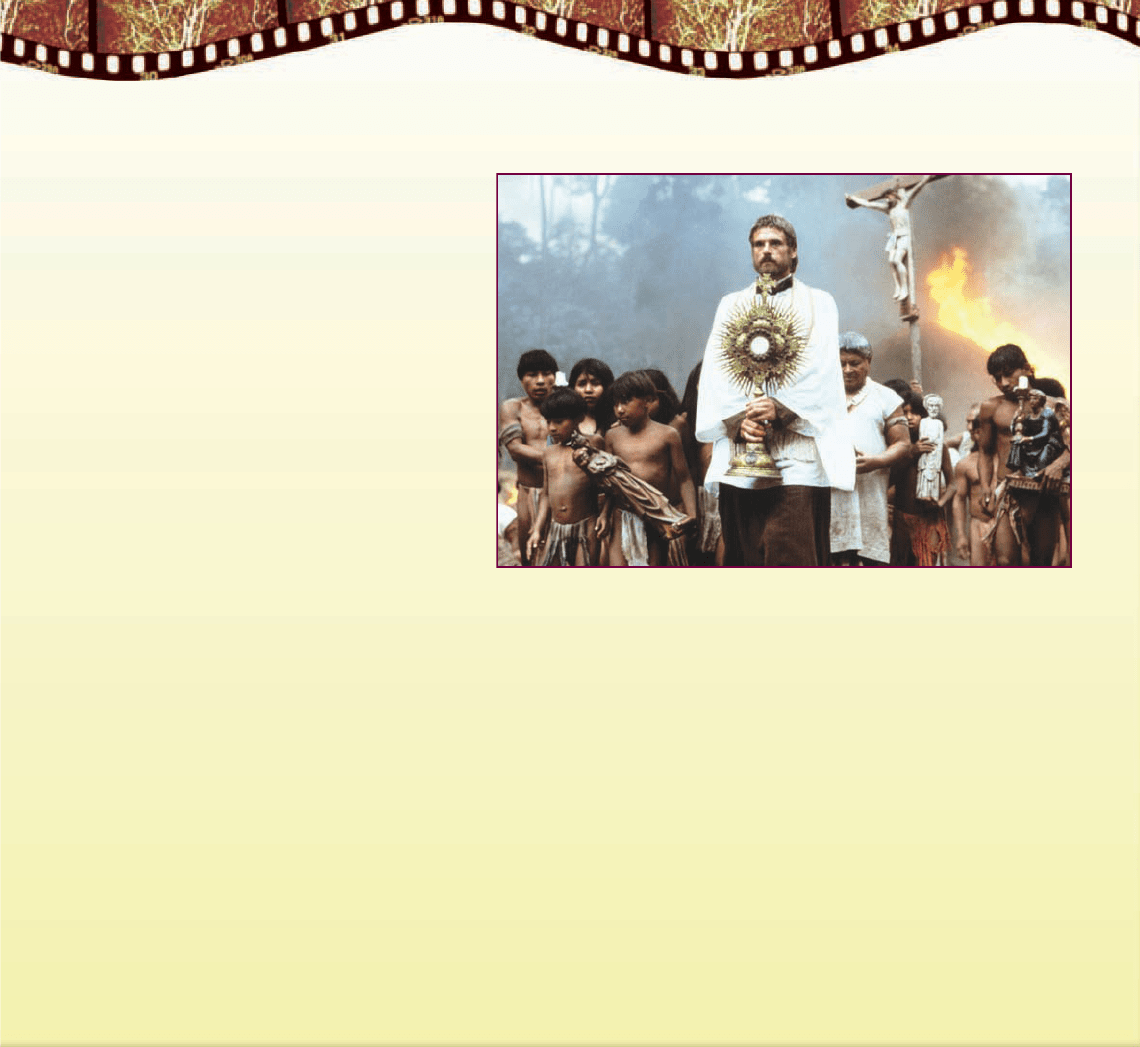

FILM & HISTORY

T

HE MISSION (1986)

Directed by Roland Joff

e, The Mission examines religion,

politics, and colonialism in Europe and South America

in the mid-eighteenth century. The movie begins with a

flashback as Cardinal Altamirano (Ray McAnally) is dic-

tating a letter to the pope to discuss the fate of the Jesuit

missions in Paraguay. He begins by describing the estab-

lishment of a new Jesuit mission (San Carlos) in Spanish

territory in the borderlands of Paraguay and Brazil. Fa-

ther Gabriel (Jeremy Irons) has been able to win over

the Guaran

ı Indians and create a community at San Car-

los that is based on communal livelihood and property

(private property is abolished). The mission includes

dwellings and a church where the Guaran

ı can practice

their new faith. This small community is joined by

Rodrigo Mendozo (Robert De Niro), who had been a

slave trader dealing in Indians and now seeks to atone

for killing his brother in a fit of jealous rage by joining

the mission at San Carlos. Won over to Father Gabriel’s

perspective, he also becomes a member of the Jesuit

order.

Soon, however, Cardinal Altamirano travels to South America,

sent by a pope anxious to appease the Portuguese monarch who has

been complaining about the activities of the Jesuits. Portuguese set-

tlers in Brazil are eager to use the native people as slaves and to

confiscate their communal lands and property. In 1750, when Spain

agrees to turn over the Guaran

ı territory in Paraguay to Portugal,

the settlers seize their opportunity. Although the cardinal visits a

number of missions, including San Carlos, and obviously approves

of their accomplishments, his hands are tied by the Portuguese king,

who is threatening to disband the Jesuit order if the missions are

not closed. The cardinal acquiesces, and Portuguese troops are sent

to take over the missions. Although Rodrigo and the other Jesuits

join the natives in fighting the Portuguese while Father Gabriel re-

mains nonviolent, all are massacred. The cardinal returns to Europe,

dismayed by the murderous activities of the Portuguese but hopeful

that the Jesuit order will be spared. All is in vain, however, as the

Catholic monarchs of E ur ope expel the J esuits from their countries and

pressure Pope Clement XIV into disbanding the Jesuit order in 1773.

In its approach to the destruction of the Jesuit missions, The

Mission clearly exalts the dedication of the Jesuits and their devotion

to the welfare of the Indians. The movie ends with a small group of

Guaran

ı children, all now orphans, picking up a few remnants of

debris left in their destroyed mission and moving off down the river

back into the wilderness to escape enslavement. The final words on

the screen reinforce the movie’s message about the activities of the

Europeans who destroyed the native civilizations in their conquest

of the Americas: ‘‘The Indians of South America are still engaged in

a struggle to defend their land and their culture. Many of the priests

who, inspired by faith and love, continue to support the rights of

the Indians, do so with their lives,’’ a reference to the ongoing strug-

gle in Latin America against regimes that continue to oppress the

landless masses.

The Jesuit missionary Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons) with the Guaran

ı Indians of Paraguay

before their slaughter by Portuguese troops

c

Warner Brothers/Courtesy Everett Collection

446 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

Canada and the lands east of the Mississippi. After the

Seven Years’ War, British policy makers sought to obtain

new revenues from the colonies to pay for the British

army’s expenses in defending the colonists. An attempt

to levy new taxes by the Stamp Act of 1765, however, led

to riots and the law’s quick repeal.

The Americans and the British had different con-

ceptions of empire. The British envisioned a single empire

with Parliament as the supreme authority throughout.

The Americans, in contrast, had their own representative

assemblies. They believed that neither king nor Parlia-

ment should interfere in their internal affairs and that no

tax could be levied without the consent of their own

assemblies.

Crisis followed crisis in the 1770s until 1776, when

the colonists decided to declare their independence from

Great Britain. On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental

Congress approved a declaration of independence drafted

by Thomas Jefferson. A stirring political document, the

Declaration of Independence affirmed the Enlighten-

ment’s natural rights of ‘‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of

happiness’’ and declared the colonies to be ‘‘free and in-

dependent states absolved from all allegiance to the

British crown.’’ The war for American independence had

formally begun.

Of great importance to the colonies’ cause was their

support by foreign countries who were eager to gain re-

venge for earlier defeats at the hands of the British. French

officers and soldiers served in the American Continental

Army under George Washington as commander in chief.

When the British army of General Cornwallis was forced

to surrender to a combined American and French army

and French fleet under Washington at Yorktown in 1781,

the British decided to call it quits. The Treaty of Paris,

signed in 1783, recognized the independence of the

American colonies and granted the Americans control of

the territory from the Appalachians to the Mississippi

River.

Birth of a New Nation The thirteen American colonies

had gained their independence, but a fear of concentrated

power and concern for their own interests caused them to

have little enthusiasm for establishing a united nation

with a strong central government, and so the Articles of

Confederation, ratified in 1781, did not create one. A

movement for a different form of national government

soon arose. In the summer of 1787, fifty-five delegates

attended a convention in Philadelphia to revise the Articles

of Confederation. The conv ention’ s delegates---wealthy,

politically experienced, and well educated---rejected revi-

sion and decided in stead to devise a new c onstitution.

The proposed United States Constitution established

a central government distinct from and superior to

governments of the individual states. The central or

federal government was divided into three branches, each

with some power to check the functioning of the others.

A president would serve as the chief executive with the

power to execute laws, veto the legislature’s acts, supervise

foreign affairs, and direct military forces. Legislative

power was vested in the second branch of government, a

bicameral legislature composed of the Senate, elected by

the state legislatures, and the House of Representatives,

elected directly by the people. A supreme court and other

courts ‘‘as deemed necessary’’ by Congress provided the

third branch of government. They would enforce the

Constitution as the ‘‘supreme law of the land.’’

The Constitution was approved by the states---by a

slim margin. Important to its success was a promise to

add a bill of rights to the Constitution as the new gov-

ernment’s first piece of business. Accordingly, in March

1789, the new Congress enacted the first ten amendments

to the Constitution, ever since known as the Bill of

Rights. These guaranteed freedom of religion, speech,

press, petition, and assembly, as well as the right to bear

arms, protection against unreasonable searches and ar-

rests, trial by jury, due process of law, and protection of

property rights. Many of these rights were derived from

the natural rights philosophy of the eighteenth-century

philosophes and the American colonists. Is it any wonder

that many European intellectuals saw the American

Revolution as the embodiment of the Enlightenment’s

political dreams?

Toward a New Political Order

and Global Conflict

Q

Focus Question: What do historians mean by the

term enlightened absolutism, and to what degree did

eighteenth-century Prussia, Austria, and Russia exhibit

its characteristics?

There is no doubt that Enlightenment thought had some

impact on the political development of European states in

the eighteenth century. The philosophes believed in nat-

ural rights, which were thought to be privileges that

ought not to be withheld from any person. These natural

rights included equality before the law, freedom of reli-

gious worship, freedom of speech and press, and the

rights to assemble, hold property, and pursue happiness.

But how were these natural rights to be established

and preserved? Most philosophes believed that people

needed to be ruled by an enlightened ruler. What, how-

ever, made rulers enlightened? They must allow religious

toleration, freedom of speech and press, and the rights of

private property. They must foster the arts, sciences, and

TOWARD A NEW POLITICAL ORDER AND GLOB A L CONFLICT 447

education. Above all, they must obey the laws and enforce

them fairly for all subjects. Only strong monarchs seemed

capable of overcoming vested interests and effecting the

reforms society needed. Reforms then should come from

above (from absolute rulers) rather than from below

(from the people).

Many historians once assumed that a new type of

monarchy emerged in the later eighteenth century, which

they called enlightened despotism or enlightened abso-

lutism. Monarchs such as Frederick II of Prussia, Cath-

erine the Great of Russia, and Joseph II of Austria

supposedly followed the advice of the philosophes and

ruled by enlightened principles. Recently, however,

scholars have questioned the usefulness of the concept of

enlightened absolutism. We can determine the extent to

which it can be applied by examining the major

‘‘enlightened absolutists’’ of the late eighteenth century.

Prussia

Frederick II, known as Frederick the Great (1740--1786),

was one of the best-educated and most cultured monarchs

of the eighteenth century . He was well versed in Enlight-

enment thought and even invited Voltaire to live at his

court for several years. A believer in the king as the ‘‘first

servant of the state,’’ Frederick the Great was a conscientious

ruler who enlarged the Prussian army (to 200,000 men) and

kept a strict watch o ver the bureaucracy .

For a time, Frederick seemed quite willing to make

enlightened reforms. He abolished the use of torture ex-

cept in treason and murder cases and also granted limited

freedom of speech and press, as well as complete religious

toleration. His efforts were limited, however, as he kept

Prussia’s rigid social structure and serfdom intact and

avoided any additional reforms.

The Austrian Empire of the Habsburgs

The Austrian Empire had become one of the great Eu-

ropean states by the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Yet it was difficult to rule because it was a sprawling

conglomerate of nationalities, languages, religions, and

cultures (see Map 18.2).

Joseph II (1780--1790) believed in the need to sweep

away anything standing in the path of reason. As he said,

‘‘I have made Philosophy the lawmaker of my empire; her

logical applications are going to transform Austria.’’

Joseph’s reform program was far-reaching. He abolished

serfdom, abrogated the death penalty, and established the

principle of equality of all before the law. Joseph insti-

tuted drastic religious reforms as well, including complete

religious toleration.

Joseph’s reform program proved overwhelming for

Austria, however. He alienated the nobility by freeing the

serfs and alienated the church by his attacks on the mo-

nastic establishment. Joseph realized his failure when he

wrote the epitaph for his own gravestone: ‘‘Here lies Jo-

seph II, who was unfortunate in everything that he un-

dertook.’’ His successors undid many of his reforms.

Russia Under Catherine the Great

Catherine II the Great (1762--1796) was an intelligent

woman who was familiar with the works of the phi-

losophes and seemed to favor enlightened reforms. She

invited the French philosophe Diderot to Russia and,

when he arrived, urged him to speak frankly ‘‘as man to

man.’’ He did, outlining a far-reaching program of po-

litical and financial reform. But Catherine was skeptical

about impractical theories, which, she said, ‘‘would have

turned everything in my kingdom upside down.’’ She did

consider the idea of a new law code that would recognize

the principle of the equality of all people in the eyes of the

law. But in the end she did nothing, knowing that her

success depended on the support of the Russian nobility.

In 1785, she gave the nobles a charter that exempted them

from taxes. Catherine’s policy of favoring the landed

nobility led to even worse conditions for the Russian

peasants and sparked a rebellion, but it soon faltered and

collapsed. Catherine responded with even harsher mea-

sures against the peasantry.

Above all, Catherine proved a worthy successor to

Peter the Great in her policies of territorial expansion

westward into Poland and southward to the Black Sea.

Russia spread southward by defeating the Turks. Russian

expansion westward occurred at the expense of neigh-

boring Poland. In three partitions of Poland, Russia

gained about 50 percent of Polish territory.

Enlightened Absolutism Reconsidered

Of the rulers we have discussed, only Joseph II sought

truly radical changes based on Enlightenment ideas. Both

Frederick II and Catherine II liked to talk about en-

lightened reforms, and they even attempted some. But

neither ruler’s policies seemed seriously affected by En-

lightenment thought. Necessities of state and mainte-

nance of the existing system took precedence over reform.

Indeed, many historians maintain that Joseph, Frederick,

and Catherine were all primarily guided by a concern for

the power and well-being of their states. In the final

analysis, heightened state power was used to create armies

and wage wars to gain more power.

It would be foolish, however, to overlook the fact that

the ability of enlightened rulers to make reforms was also

448 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

limited by political and social realities. Everywhere in

Europe, the hereditary aristocracy was still the most

powerful class in society. As the chief beneficiaries of a

system based on traditional rights and privileges for their

class, the nobles were not willing to support a political

ideology that trumpeted the principle of equal rights for

all. The first serious challenge to their supremacy would

come with the French Revolution, an event that blew

open the door to the modern world of politics.

Changing Patterns of War:

Global Confrontation

The philosophes condemned war as a foolish waste of

life and resources in stupid quarrels of no value to

humankind. Despite their criticisms, the rivalry among

European states that led to costly struggles continued

unabated. Eighteenth-century Europe consisted of a

number of self-governing, individual states that were

chiefly guided by the self-interest of the ruler. And as

Frederick the Great of Prussia said, ‘‘The fundamental

rule of governments is the principle of extending their

territories.’’

By far the most dramatic confrontation occurred in

the Seven Years’ War. Although it began in Europe, it

soon turned into a global conflict fought in Europe, In-

dia, and North America. In Europe, the British and

Prussians fought the Austrians, Russians, and French.

With his superb army and military skill, Frederick the

Great of Prussia was able for some time to defeat the

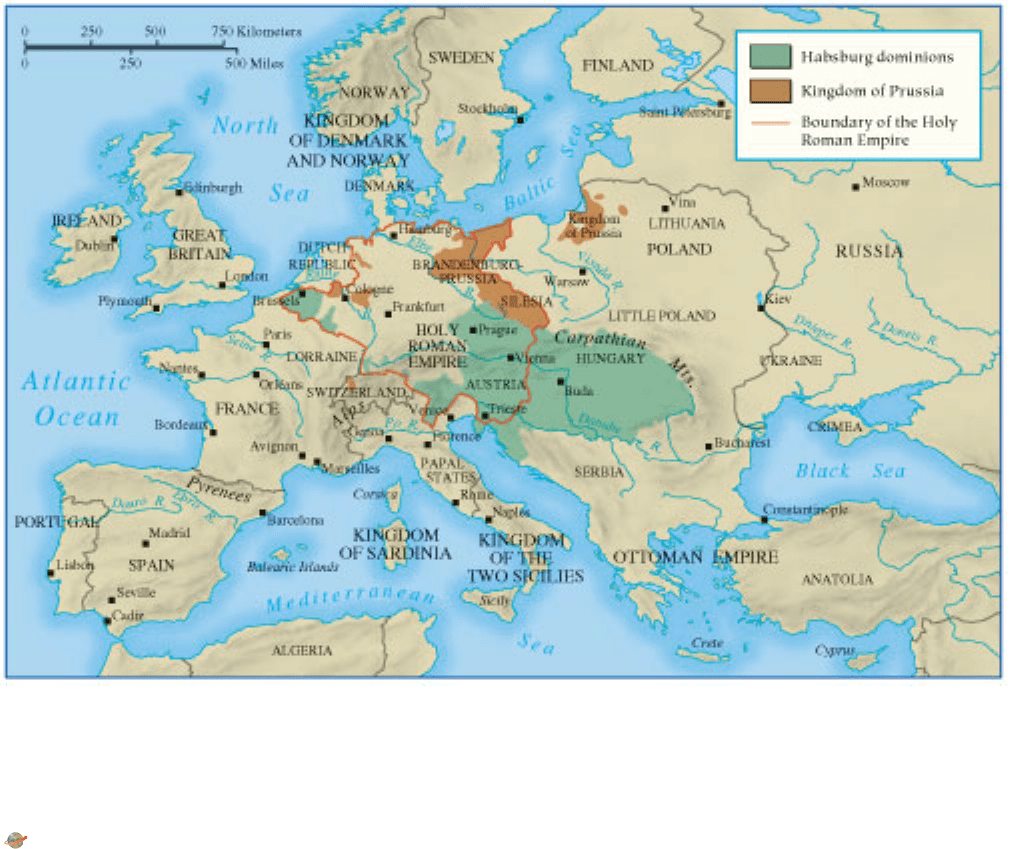

MAP 18.2 Europe in 1763. By the middle of the eighteenth century, five major powers

dominated Europe—Prussia, Austria, Russia, Britain, and France. Each sought to enhance its

power both domestically, through a bureaucracy that collected taxes and ran the military, and

internationally, by capturing territory or preventing other powers from doing so.

Q

Given the distribution of P russian and H absburg holdings, in what ar eas of E ur ope were

they most likely to compete for land and power?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .c engage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

TOWARD A NEW POLITICAL ORDER AND GLOB A L CONFLICT 449

Austrian, French, and Russian armies. Eventually, how-

ever, his forces were gradually worn down and faced utter

defeat until a new Russian tsar withdrew Russia’s troops

from the conflict. A stalemate ensued, ending the Euro-

pean conflict in 1763.

The struggle between Britain and France in the rest of

the world had more decisive results. In India, local rulers

allied with British and French troops fought a number of

battles. Ultimately, the British under Robert Clive won

out, not because they had better forces but because they

were more persistent. By the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the

French withdrew and left India to the British.

The greatest conflicts of the Seven Years’ War took

place in North America, where it was known as the

French and Indian War. French North America (Canada

and Louisiana) was thinly populated and run by the

French government as a vast trading area. British North

America had come to consist of thirteen colonies on the

eastern coast of the present United States. These were

thickly populated, containing about 1.5 million people by

1750, and were also prosperous.

British and French rivalry finally led war. Despite

initial French successes, the British went on to seize

Montreal, the Great Lakes area, and the Ohio valley. The

French were forced to make peace. By the Treaty of Paris,

they ceded Canada and the lands east of the Mississippi to

Britain. Their ally Spain transferred Spanish Florida to

British control; in return, the French gave their Louisiana

territory to the Spanish. By 1763, Great Britain had be-

come the world’s greatest colonial power. For France, the

loss of its empire was soon followed by an even greater

internal upheaval.

The French Revolution

Q

Focus Question: What were the causes, the main

events, and the results of the French Revolution?

The year 1789 witnessed two far-reaching events, the

beginning of a new United States of America under its

revamped Constitution and the eruption of the French

Revolution. Compared with the American Revolution a

decade earlier, the French Revolution was more complex,

more violent, and far more radical in its attempt to

construct both a new political and a new social order.

Background to the French Revolution

The root causes of the French Revolution must be sought

in the condition of French society. Before the Revolution,

France was a society grounded in privilege and inequality.

Its population of 27 million was divided, as it had been

since the Middle Ages, into three orders or estates.

Social Structure of the Old Regime The first estate

consisted of the clergy and numbered about 130,000

people who owned approximately 10 percent of the land.

Clergy were exempt from the taille, France’s chief tax.

Clergy were also radically divided: the higher clergy,

stemming from aristocratic families, shared the interests

of the nobility, while the parish priests were often poor

and from the class of commoners.

The second estate was the nobility, composed of

about 350,000 people who owned about 25 to 30 percent

of the land. The nobility had continued to play an im-

portant and even crucial role in French society in the

eighteenth century, holding many of the leading positions

in the government, the military, the law courts, and the

higher church offices. The nobles sought to expand their

power at the expense of the monarchy and to maintain

their control over positions in the military, church, and

government. Common to all nobles were tax exemptions,

especially from the taille.

The third estate, or the commoners of society, con-

stituted the overwhelming majority of the French

population. They were divided by vast differences in

occupation, level of education, and wealth. The peasants,

who alone constituted 75 to 80 percent of the total

population, were by far the largest segment of the third

estate. They owned about 35 to 40 percent of the land,

although their landholdings varied from area to area and

more than half had little or no land on which to survive.

Serfdom no longer existed on any large scale in France,

but French peasants still had obligations to their local

landlords that they deeply resented. These ‘‘relics of feu-

dalism,’’ or aristocratic privileges, were obligations that

survived from an earlier age and included the payment of

fees for the use of village facilities, such as the flour mill,

community oven, and winepress.

Another part of the third estate consisted of skilled

craftspeople, shopkeepers, and other wage earners in the

cities. In the eighteenth century , c onsumer prices had risen

faster than wages, causing these urban groups to experience

a noticeable decline in purchasing power. Engaged in a

daily struggle for survival, many of these people would play

an important r ole in the Rev olution, especially in Paris.

About 8 percent of the population, or 2.3 million

people, constituted the bourgeoisie or middle class, who

owned about 20 to 25 percent of the land. This group

included merchants, industrialists, and bankers who

controlled the resources of trade, manufacturing, and fi-

nance and benefited from the economic prosperity after

1730. The bourgeoisie also included professional people---

lawyers, holders of public offices, doctors, and writers.

Many members of the bourgeoisie had their own set of

grievances because they were often excluded from the

social and political privileges monopolized by nobles.

450 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

Moreover, the new political ideas of the Enlighten-

ment proved attractive to both the aristocracy and the

bourgeoisie. Both elites, long accustomed to a new so-

cioeconomic reality based on wealth and economic

achievement, were increasingly frustrated by a monar-

chical system resting on privileges and on an old and rigid

social order based on the concept of estates. The oppo-

sition of these elites to the old order led them ultimately

to drastic action against the monarchical old regime. In a

real sense, the Revolution had its origins in political

grievances.

Other Problems Facing the French Monarc hy The

inability of the French monarchy to deal with new social

realities was exacerbated by specific problems in the

1780s. Although France had enjoyed fifty years of eco-

nomic expansion, bad harvests in 1787 and 1788 and the

beginnings of a manufacturing depression resulted in

food shortages, rising prices for food and other goods,

and unemployment in the cities. The number of poor,

estimated at almost one-third of the population, reached

crisis proportions on the eve of the Revolution.

The immediate cause of the French Revolution was

the near collapse of government finances. Costly wars and

royal extravagance drove French governmental ex-

penditures ever higher. On the verge of a complete

financial collapse, the government of Louis XVI (1774--

1792) was finally forced to call a meeting of the Estates-

General, the French parliamentary body that had not met

since 1614.

The Estates-General consisted of representatives from

the three orders of French society. In the elections for the

Estates-General, the government had ruled that the third

estate should get double representation (it did, after all,

constitute 97 percent of the population). Consequently,

while both the first estate (the clergy) and the second

estate (the nobility) had about three hundred delegates

each, the third estate had almost six hundred repre-

sentatives, most of whom were lawyers from French

towns.

From Estates-General to National Assembly

The Estates-General opened at Versailles on May 5, 1789.

It was troubled from the start with the question of

whether voting should be by order or by head (each

delegate having one vote). Traditionally, each order would

vote as a group and have one vote. That meant that the

first and second estates could outvote the third estate two

to one. The third estate demanded that each deputy have

one vote. With the assistance of liberal nobles and clerics,

that would give the third estate a majority. When the first

estate declared in favor of voting by order, the third estate

responded dramatically. On June 17, 1789, the third estate

declared itself the ‘‘National Assembly’’ and decided to

draw up a constitution. This was the first step in the

French Revolution because the third estate had no legal

right to act as the National Assembly. But this audacious

act was soon in jeopardy, as the king sided with the first

estate and threatened to dissolve the Estates-General.

Louis XVI now prepared to use force.

The common people, however, saved the third estate

from the king’s forces. On July 14, a mob of Parisians

stormed the Bastille, a royal armory, and proceeded to

dismantle it, brick by brick. Louis XVI was soon informed

that the royal troops were unreliable. Louis’s acceptance

of that reality signaled the collapse of royal authority; the

king could no longer enforce his will.

At the same time, popular revolts broke out

throughout France, both in the cities and in the coun-

tryside (see the comparative illustration on p. 452). Be-

hind the popular uprising was a growing resentment of

the entire landholding system, with its fees and obliga-

tions. The fall of the Bastille and the king’s apparent ca-

pitulation to the demands of the third estate now led

peasants to take matters into their own hands. The peas-

ant rebellions that occurred throughout France had a great

impact on the National Assembly meeting at Versailles.

Destruction of the Old Regime

One of the first acts of the National Assembly was to

abolish the rights of landlords and the fiscal exemptions

of nobles, clergy, towns, and provinces. Three weeks later,

the National Assembly adopted the Declaration of the

Rights of Man and the Citizen (see the box on p. 453).

This charter of basic liberties proclaimed freedom and

equal rights for all men and access to public office based

on talent. All citizens were to have the right to take part in

the legislative process. Freedom of speech and the press

was coupled with the outlawing of arbitrary arrests.

The declaration also raised another important issue.

Did its ideal of equal rights for ‘‘all men’’ also include

women? Many deputies insisted that it did, provided that,

as one said, ‘‘women do not hope to exercise political

rights and functions.’’ Olympe de Gouges, a playwright,

refused to accept this exclusion of women from political

rights. Echoing the words of the official declaration, she

penned the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the

Female Citizen, in which she insisted that women should

have all the same rights as men. The National Assembly

ignored her demands.

Because the Catholic church was seen as an important

pillar of the old order, it too was reformed. Most of the

lands of the church were seized. The new Civil Consti-

tution of the Clergy was put into effect. Both bishops and

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 451

priests were to be elected by the people and paid by the

state. The Catholic church, still an important institution

in the life of the French people, now became an enemy of

the Revolution.

By 1791, the National Assembly had finally com-

pleted a new constitution that established a limited con-

stitutional monarchy. There was still a monarch (now

called ‘‘king of the French’’), but the new Legislative As-

sembly was to make the laws. The Legislative Assembly, in

which sovereign power was vested, was to sit for two years

and consist of 745 representatives chosen by an indirect

system of election that preserved power in the hands of

the more affluent members of society. A small group of

50,000 electors chose the deputies.

By 1791, the old order had been destroyed. Many

people, however---including Catholic priests, nobles,

lower classes hurt by a rise in the cost of living, peasants

opposed to dues that had still not been eliminated, and

political clubs like the Jacobins that offered more radical

solutions to France’s problems---opposed the new order.

The king also made things difficult for the new govern-

ment when he sought to flee France in June 1791 and

almost succeeded before being recognized, captured, and

brought back to Paris. In this unsettled situation, under a

discredited and seemingly disloyal monarch, the new

Legislative Assembly held its first session in October 1791.

France’s relations with the rest of Europe soon led to

Louis’s downfall.

On August 27, 1791, the monarchs of Austria and

Prussia, fearing that revolution would spread to their

countries, invited other European monarchs to use force

to reestablish monarchical authority in France. The

French fared badly in the initial fighting in the spring of

1792, and a frantic search for scapegoats began. As one

observer noted, ‘‘Everywhere you hear the cry that

the king is betraying us, the generals are betraying

us, that nobody is to be trusted; ... that Paris will

be taken in six weeks by the Austrians. ... We are

on a volcano ready to spout flames.’’

3

Defeats in

war coupled with economic shortages in the

spring led to renewed political demonstrations,

especially against the king. In August 1792, radical

political groups in Paris took the king captive and

forced the Legislative Assembly to suspend the

monarchy and call for a national convention,

chosen on the basis of universal male suffrage, to

decide on the future form of government. The

French Revolution was about to enter a more

radical stage.

COMPARATIVE

ILLUSTRATION

Revolution and Revolt in France

and China.

Both France and

China experienced revolutionary upheaval at the

end of the eighteenth century and well into the

nineteenth century. In both countries, common

people often played an important role. At the

right is a scene from the storming of the

Bastille in 1789. This early success ultimately

led to the overthrow of the French monarchy.

At the top is a scene from one of the struggles

during the Taiping Rebellion, a major peasant

revolt in the mid-nineteenth century in China.

An imperial Chinese army is shown recapturing

the city of Nanjing from Taiping rebels in 1864.

Q

What role did common people play in

revolutionary upheavals in France and China in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries?

c

The Art Archive/School of Oriental and African Studies, London/Eileen Tweedy

c

The Bridgeman Art Library

452 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

The Radical Revolution

In September 1792, the newly elected National Conven-

tion began its sessions. Dominated by lawyers and other

professionals, two-thirds of its deputies were under forty-

five, and almost all had gained political experience as a

result of the Revolution. Almost all distrusted the king. As

a result, the convention’s first step on September 21 was

to abolish the monarchy and establish a republic. On

January 21, 1793, the king was executed, and the de-

struction of the old regime was complete. But the exe-

cution of the king created new enemies for the Revolution

both at home and abroad.

In Paris, the local government, known as the Com-

mune, whose leaders came from the working classes, fa-

vored radical change and put constant pressure on the

convention, pushing it to ever more radical positions.

Moreover, peasants in the west and inhabitants of the

major provincial cities refused to accept the authority of

the convention.

A foreign crisis also loomed large. By the beginning

of 1793, after the king had been executed, most of

Europe---an informal coalition of Austria, Prussia, Spain,

Portugal, Britain, the Dutch Republic, and even Russia---

aligned militarily against France. Grossly overextended,

the French armies began to experience reverses, and by

late spring, France was threatened with invasion.

A Nation in Arms To meet these crises, the convention

gave broad powers to an executive committee of twelve

known as the Committee of Public Safety, which came to

be dominated by Maximilien Robespierre. For a twelve-

month period, from 1793 to 1794, the Committee of

Public Safety took control of France. To save the Republic

from its foreign foes, on August 23, 1793, the committee

DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MAN AND THE CITIZEN

One of the important documents of the French

Revolution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man

and the Citizen was adopted in August 1789 by

the National Assembly. The declaration affirmed

that ‘‘men are born and remain free and equal in rights,’’ that

governments must protect these natural rights, and that politi-

cal power is derived from the people.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen

The representatives of the French people, organized as a national

assembly, considering that ignorance, neglect, and scorn of the

rights of man are the sole causes of public misfortunes and of cor-

ruption of governments, have resolved t o display in a solemn dec-

laration the natural, inalienable, and sacred rights of man, so that

this declaration , constantly in the presence of all mem bers of

society, will continually remind them of their rights and their

duties. ... Consequently, the National Assembly recognizes and

declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme

Being, the following rights of man and citizen:

1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights; social dis-

tinctions can be established only for the common benefit.

2. The aim of every political association is the conservation of the

natural and imprescriptible rights of man; these rights are lib-

erty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

3. The source of all sovereignty is located in essence in the nation;

no body, no individual can exercise authority which does not

emanate from it expressly.

4. Liberty consists in being able to do anything that does not

harm another person. ...

6. The law is the expression of the general w ill; all citizens have

the right to concur personally or through their representatives

in its formation; it must be the same for all, whether it protects

or punishes. All citizens being equal in its eyes are equally ad-

missible to all honors, positions, and public employments,

according to their capabilities and without other distinctions

than those of their virtues and talents.

7. No man can be accused, arrested, or detained except in cases

determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has

prescribed. ...

10. No one may be disturbed because of his opinions, even reli-

gious, provided that their public demonstration does not dis-

turb the public order established by law.

11. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of

the most precious rights of man: every citizen can therefore

freely speak, write, and print. ...

14. Citizens have the right to determine for themselves or through

their representatives the need for taxation of the public, to

consent to it freely, to investigate its use, and to determine

its rate, basis, collection, and duration. ...

16. Any societ y in which guarantees of rights are not

assured nor the separation of powers determined has

no constitution.

Q

What ‘‘natural rights’’ does this document proclaim? To

what extent was the document influenced by the writings of

the philosophes? What similarities exist between this French

document and the American Declaration of Independence?

Why do such parallels exist?

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 453